Abstract

Background. Current therapies for adenocarcinoma of the pancreas do not improve the life expectancy of patients. Methods. In a non-randomized pilot trail we tested whether a local therapy based upon an adenoviral gene transfer of wild type p53 in combination with gemcitabine administration would be safe in patients with liver metastases due to pancreatic carcinoma. We report on the clinical course of three patients with respect to safety, tolerability and tumor response. Results. Transient grade III toxicities occurred with fever, leucopenia, elevation of AP, ALT, AST, GGT, while grade IV toxicity occurred for bilirubin only. Laboratory tests suggested disseminated intravascular coagulation in all three patients, but fine needle biopsies of liver did not show any histological evidence of thrombus or clot formation. Progression of liver metastases was documented in one and stable disease in another patient two months after treatment. However, a major improvement with regression of the indexed lesion by 80% occurred in a third patient after a single administration of 7.5×1012 viral particles, and time to progression was extended to six months. Conclusion. The combination therapy of viral gene transfer and chemotherapy temporarily controls and diminishes tumor burden. Improvement of the toxicity profile is necessary. Further trials are warranted to improve treatment and life expectancy of patients suffering from fatal diseases such as pancreatic carcinoma.

Keywords: Adenovirus, p53 gene transfer, liver metastases, pancreatic carcinoma

Introduction

The prognosis of pancreatic carcinoma is poor. Most patients already have advanced disease at the time of diagnosis. The 5-year survival rate is around 10% and depends on the stage, with a median survival of only 6 months 1,2. Surgery in the form of pancreaticoduodenectomy offers the only possibility of a cure 3. However, the 5-year-survival rates after surgery do not exceed 20% in pancreatic carcinoma 2, due to early hepatic metastases. Specific mutations in a number of genes like K-ras, CDKN2A, BRCA2, SMAD4/DPC4 and p53 have been recognized as signature lesions involved in and causing progression of the disease. Among the mutated genes, the p53 tumor suppressor gene is altered in more than 70% of patients 4,5, which deprives cells of protection against ill-defined breakage-fusion-bridge cycles, and allowing for subsequent oncogenic alterations.

Gene transfer therapy could improve the treatment of pancreatic carcinoma, with adenoviruses being among the most promising vectors for this therapy 6. The transfer of the wild-type tumor suppressor gene p53 into cancer cells in order to restore its lost function in DNA damage control was demonstrated to induce apoptosis in various cells in vitro and in the mouse model 7, which has prompted its introduction in antitumor strategies against pancreatic carcinoma. Indeed, increased tumor cell apoptosis and reduced cell growth in human pancreatic carcinoma cell line derived tumors has been demonstrated in nude mice after adenoviral p53 transfer 8,9. Likewise, an adenoviral vector expressing p21, a downstream effector of p53, reduced tumor cell growth, presumably through reverting cell cycle from S to G0/G1 phase 10. Vector-mediated introduction of the wild-type retinoblastoma gene resulted in growth inhibition but not apoptosis 11. Several other strategies of gene transfer therapies for pancreatic carcinoma have been investigated in mice, among them suicide gene prodrug systems utilizing cytine deaminase, thymidine kinase or UPRT 12,13,14,15,16,17, attempts to develop CaSM-antisense strategies 18, somatostatin receptor transfer 19 or ribozymes that modulate expression of K-ras 20.

However, a number of limitations dampened early hopes and have prevented the broader use of gene transfer therapies. Major among these are the risk of disseminating viral vectors, and the potential for severe toxicity sometimes seen with adenoviral vectors 21. High doses systemic administration of non-replicating E1-deleted adenoviral vectors has caused hepatic necrosis and death in number of animal models including primates. Especially with increasing amounts of vector such as might be necessary to achieve an effective systemic dosage there is evidence for such toxicity 22,23. Liver toxicity occurring after vector administration is substantially milder in replication incompetent than in replication competent vectors in animal modeling 24. However, tolerability and the level of toxicity observed in phase I and phase II trials utilizing conditionally replication competent adenovectors to treat hepatocellular carcinoma or liver metastases of colorectal cancer have warranted further trials 25,26. Still, hepatotoxicity is a major concern in treating tumors metastatic to the liver.

To date, there is still limited information available on clinical trials utilizing adenoviral gene transfer for metastatic pancreatic carcinoma, and few of the strategies explored in animal modelling have been evaluated for safety and efficacy in the treatment of human diseases. We conducted a phase I/II pilot study to treat patients with liver metastasis due to advanced pancreatic carcinoma with immunohistologically proven p53 mutation. An intravenous gemcitabine chemotherapy was followed on subsequent days by administration of a p53-expressing, replication incompetent adenoviral vector rAV/p53 via the coeliac artery.

Materials and methods

Study design and patients

A non-randomized, non-controlled, open-label, phase I/II pilot study of a recombinant replication-defective and p53-expressing adenoviral vector in combination with weekly administration of gemcitabine (2’,2'di-fluorodeoxycytidine) has been initialized in patients with advanced stage of pancreatic carcinoma.

Patients between the ages of 18 and 75 years with histologically confirmed and metastatic carcinoma and stable or progressive disease which was considered to be incurable have been eligible. Those who had an identified measurable index lesion, immunohistochemical accumulation of p53 as evidence of its gene mutation, adequate performance status and laboratory tests and fulfilling all inclusion criteria were enrolled in the study.

The treatments were conducted as approved by the ethical board committee of the Dresden University of Technology. Informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to treatment. The patients received full supportive care.

Treatment schedule and vector

Gemcitabine Therapy

The treatment schedule is summarized in Table 1. Gemcitabine (Gemzar, Lilly Deutschland GmbH, Bad Homburg, Germany) at 1000 mg/m2 was diluted in 100 mL normal saline and administered intravenously over 30 min once per week (on day 1, day 8, day 15 etc). In patient 2 and 3, gemcitabine has not been administered on day 8.

Table 1. Treatment Schedule.

| Day |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | Treatment | 1 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 15 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 29 | 36 | 43 | 50 |

| 1 | rAd/p53, 2.5×1012 v.p. | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Gemcitabine | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| 2 | rAd/p53, 2.5×1012 v.p. | X | X | ||||||||||

| Gemcitabine | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| 3 | rAd/p53, 7.5×1012 v.p. | X | |||||||||||

| Gemcitabine | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

After a single day of Gemcitabine intravenously, rAd/p53 was injected into the celiac artery on the following day(s), followed by 1 d of intravenous Gemcitabine per week for three weeks.

Adenoviral Vector and Administration

rAd/p53 (SCH 58500, Essex Pharma GmbH, München, Germany) is a serotype 5 based replication–defective adenoviral vector. An expression cassette containing the human cytomegalovirus immediate early promoter and enhancer element, the adenovirus serotype 2 tripartite leader and the human p53 wild type cDNA has been introduced into region E1 29. rAd/p53 was grown and purified according to standard procedures and in accordance with GLP/GCP. The IV treatment formulation was kindly provided by Schering-Plough (SCH 58500, Essex Pharma GmbH, Munich, Germany).

Dosages of 2.5×1012 viral particles twice on successive days (patients 1 and 2) and in a planned dose escalation 7.5×1012 (patient 3) were injected into the coeliac artery in normal saline on days 2 and 3 in all patients and also on days 23 and 24 in patient 1 only. Administration was carried out with radiological control via a Terumo sidewinder catheter (5 F, length 100 cm, inner diameter 0.38 cm). Perfusion was visualized by injection of 30 mL Ultravist™.

Endpoints, assessment of efficacy and toxicity

Primary Endpoints, Toxicity

Patients were observed to detect any toxic effects related to any of the categories within the Common Toxicity Criteria (CTC Version 2.0) such as allergic, haematologic or cardiovascular complications, coagulopathy, constitutional, gastrointestinal, hepatic, infective, metabolic, neurologic, pulmonary, renal symptoms, pain and tumor lysis syndrome. Safety was assessed by review of laboratory studies. All laboratory studies were carried out according to commercial standard tests and the manufacturer's instructions.

Histology

Ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of the liver was done before and on day 4 after vector administration. Aspirates were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Sections of 8 µm were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde in 1×phosphate-buffered saline (10×PBS: 1.3 M NaCl, 70 mM Na2HPO4, 30 mM NaH2PO4) prior to staining with hematoxylin-eosin.

Cryostat sections were immunostained for p53 (DO-1 anti-p53 monoclonal mouse antibody, Dianova, Hamburg, Germany). The specimens were exposed to the specific antiserum for 12 h at 4°C at dilutions of 1:100. The reaction was visualized using the avidin-biotin staining method according to the catalyzed signal amplification (CSA) system (Dako, Hamburg, FRG) with AEC chromogen (Immunotech, Hamburg, FRG). Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, rinsed in water and mounted in glycerol gelatin (Sigma, Munich, FRG). As a control, the specific antiserum was replaced by an isotype-immune serum (Mouse IgG1, κ [anti-TNP], Pharmingen, Hamburg, FRG).

Secondary Endpoint, Assessment of efficacy

The response of the index lesion to the treatment was assessed by thin-layer computed tomography and positron emission tomography. Positron emission tomography was performed following a fasting period of at least 12 h. Scans were obtained over 60 min after IV injection of approximately 310 MBq 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose. CT examinations were carried out every month following vector administration with month 2 examination being evaluated. Positron emission tomography was added at 2 months in case of regression or stable disease.

Results

Patient characteristics

Three male patients at 50 years (patient 1), 64 (patient 2), and 58 (patient 3) years of age were included in the study.

Painless jaundice and weight loss of 10 kg became apparent in patient 1 two months before enrolment at the age of 50 years. Ultrasound examinations revealed a tumor of the head of the pancreas and several lesions within the liver suggestive of metastases. Histological examination of an ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration of a liver lesion revealed a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Jaundice was treated with biliary prosthesis. The patient had been enrolled after informed consent was obtained.

The pathological grading and staging was pTx Nx M1 G3, UICC stage IV. Positive immunoreactivity against p53 was seen in 90% of cells with 30% poorly, 40% intermediate and 30% strongly positive cells, corresponding to a Remmele score of 8 and a Confidential immunoreactivity score (IRS) of 3+.

Patient 2 complained of a lack of appetite, mild abdominal pain and loss of weight of 8 kg within 4 months prior to diagnosis at 64 years of age. Helicobacter pylori associated gastritis was treated without relief of his symptoms. A subsequent computed tomography of the abdomen showed a tumor of the body of the pancreas and metastases in the liver. Fine needle aspiration of a liver metastasis documented an adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. The patient had been enrolled after informed consent was obtained.

The tumor was staged and graded histologically as pTx Nx M1 G3, UICC stage IV. Positive immunoreactivity against p53 was seen in 100% of tumor cells. Exact immunoreactivity scores could not be determined.

In patient 3 at the age of 58 years cholecystectomy was performed 9 months before inclusion in the trial. Three months later the symptoms of dyspepsia, diarrhoea and meteorism recurred and were accompanied by weight loss of 7 kg. Four months later he was diagnosed with a tumor in the head of the pancreas and underwent a partial duodenopancreatectomy (Whipple's procedure). Pathology examination revealed a mildly differentiated tubulo-papillous adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Five months later metastases in the liver were found. The patient was enrolled after informed consent was obtained.

The pathological grading and staging was pT2 N0 M0 G2 RO, UICC stage I, at the time of surgery. Positive p53 immunoreactivity was seen in 40% of cells with 50% poorly, 40% intermediate and 10% strongly positive cells among these, thus resembling a Remmele score of 2 and Confidential IRS of 2+.

After inclusion of three patients the study was halted because of safety concerns arising after a fatality that occurred in a human subject participating in a clinical trial for ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency 27,28 and observed grade III and grade IV toxicities in our own trail, and no further patients were treated in this protocol.

Assessment of toxicity

General performance and constitutional symptoms of patients

All patients had a Karnofsky index of 80% or higher, the BMI ranged between 22.3 and 23.8 (patient 1, 73 kg bodyweight at 181 cm height; patient 2, bodyweight 69 kg and 172 cm body height; patient 3 bodyweight 67.7 kg and 175 cm body height). Patients 1 & 2 developed chills and an increase of body temperature not exceeding 38.5°C. No immediate rise in body temperature was seen in patient 3, however, on day 8 he experienced convulsive abdominal pain accompanied by shivers and a temperature increase to 40.5°C 8 d after vector administration. The symptoms have been suggested to be related to bacterial cholangitis due to insufficiency of bile stent and resolved after change of the stent and administration of ciprofloxacin.

Cardiovascular

For all patients blood pressure and heart rate remained within the normal range after vector administration and on the following days. In patients 1 and 3 a slight decrease in blood pressure not falling below systolic 105 mmHg and diastolic 80 mmHg was observed upon immediate administration. The heart rate remained within the normal range, and no cardiovascular support was needed.

Hepatic toxicity

All patients showed an elevation of serum AST between 2.1 and 5.5 times (maximum 5.51 µmol/L*s) and of serum ALT between 1.38 and 2.8 times (maximum 3.85 µmol/L*s) compared to values before treatment (Figure 1). Total bilirubin levels ranged between 13.6 and 24 µmol/L, with a tendency to increase during progression of the disease and without notable impact of the administered therapy. A 2.5 fold increase (14,37 µmol/L*s) in lactate dehydrogenase was seen only in patient 3, who received the highest dose. Total protein and serum albumin decreased during the first 4 d, with minimal values when ALT and AST elevation reached maximum values. However, the total protein and serum albumin did not fall below the normal range. There have been no clinical signs of hepatic encephalopathy.

Figure 1. .

Blood cell count and blood chemistry after administration of rAd/p53. Elevation of liver enzymes and bilirubin occurred in all three patients albeit at differing levels and returned to pretreatment levels depending an degree of liver infiltration [3 Units and symbols for liver chemistry as follows: ▪ ALAT in µmol/L*s, □ ASAT in µmol/L*s, ▴ GGT in µmol/L*s, ▵ total Biliribin in µmol/L]. Transient alterations of coagulation profile in all three patients and indication of permanent impairement most likely due to altered liver function upon metastases [2 Units and symbols for coagulation profile as follows: ▪ Quick in %, □ PTT in sec, ▴ Fibrinogen g/L, ▵ ATIII in %]. The drop in platelets and white blood cells was transient [1 Units and symbols for coagulation profile as follows: ▪ Hemoglobin in mmol/L, □ WBC in GPt/L, * Platelets in GPt/L; ▾ or ▾▾ indicate single or repeated injections of vector].

Coagulation profile

All patients showed a slight decrease of thromboplastin time. In two patients partial thromboplastin time increased up to 1.9 times above the upper limit of normal. Disseminated intravascular coagulation was present in all three patients as defined by elevation of D-dimers. D-dimers increased above the upper limit of normal (below 1,0 µg/mL) up to 4 fold in patient 1 (4,0 µg/mL), 1.9 fold in patient 2 (1,9 µg/mL) und 8 fold in patient 3 (8,0 µg/mL).

Blood

In all patients a decline in blood components was observed. Only in patient 3, who received highest dosage leukocytes fall to 1.9×109 /L and platelets to 66×109 /L.

Tumor lysis syndrome and related

Tumor lysis syndrome was absent in the patients. No apparent changes in kidney parameters were observed. The data is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary of toxicities observed.

| CTC Grade |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | |

| Constitutional and gastrointestinal symptoms | |||

| Fever (with AGC >1.0×109/L) | 0 | 0 | [0] 3‡ |

| chills | [0] 1 | [0] 1 | [0] 1‡ |

| Nausea | 0 | 0 | [0] 2‡ |

| Vomiting | 0 | 0 | [0] 1‡ |

| Diarrhea | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pain | |||

| Myalgia (muscle pain) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Abdominal pain or cramping | [0] 1 | [0] 1 | [0] 2‡ |

| Chest pain (non-cardiac and non-pleuritic) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hepatic pain | 0 | 0 | [0] 1‡ |

| Cardiovascular/allergy/infection | |||

| Acute vascular leak syndrome | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypertension | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Allergic reaction/ hypersensitivity | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Infection | 0 | 0 | [0] 2‡ |

| Hepatic | |||

| Bilirubin | [1] 2, later 4 | [1] 4 | [0] 2‡ |

| Alkaline phosphatase | [2] 2 | [3] 3 | [1] 2‡ |

| GGT (Glutamyl transpeptidase) | [2] 3 | [3] 3 | [2] 3 |

| SGPT (ALAT) | [1] 2 | [2] 3 | [1] 2 |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SGOT (ASAT) | [1] 2 | [2] 3 | [1] 3 |

| Clinical signs of liver dysfunction* | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tumor lysis syndrome and related | |||

| Tumor lysis syndrome | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Creatinine | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypercalcemia | 0 | [0] 2 | 0 |

| Hyperkalemia | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hyperuricemia | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Coagulation | |||

| Fibrinogen | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Partial thromboplastin time (PTT) | 0 | [0] 2 | [0] 2 |

| Thromboplastin time° | 0 | [0] 1 | 0 |

| DIC (disseminated intravascular coagulation)† | [0] 3 | [0] 3 | [0] 3 |

| Thrombosis | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Blood | |||

| Hemoglobin | [0] 1 | [0] 1 | 0 |

| Leukocytes | 0 | 0 | [0] 3 |

| Platelets | 0 | [0] 1 | [0] 2 |

The highest toxicity was documented between days 4 and 6 ([/] the number in brackets represents toxicity grade if CTC criteria were applied before treatment was initiated; * asterixis, encephalopathy or coma; † defined by increased fibrin split products or D-dimer; ‡ occurring 8 d after treatment and suggested to be related to bacterial cholangitis due to insufficiency of bile stent; ° Thromboplastin time: Grade 0 within normal limits, grade 1 0.75– < 1.0×lower limit of normal; grade 2 0.5– < 0.75×lower limit of normal; grade 3 0.25– < 0.5×lower limit of normal; grade 4 <0.25×lower limit of normal).

Histological findings

On day 4 after vector administration, fine needle aspiration of liver metastases was performed. The specimens demonstrated a mild to moderate fatty degeneration of hepatocytes with anisonucleosis, slight cholestasis as well as chronic inflammation of the portal fields and within the lobuli. Of note, smaller arteries and portal vessels and sinusoids were devoid of histological signs of epithelial damage or thrombus formation. Besides this, necrotic cell clusters within the initial carcinomatous tissue were present (Figure 2).

Figure 2. .

Histologic presentation at day 4 after vector administration. The vessels have been devoid of histological signs of epithelial damage or thrombus formation (patient 2; 400×).

Assessment of efficacy

Efficacy of treatment was evaluated using thin layer computed tomography and positron emission tomography scan examinations.

Patient 1

Computed tomography showed stable disease 2 months after vector administration. Positron emission tomography suggested decreased metabolic activity of the metastases. Radiologic and clinical progression were confirmed 3 months after vector administration.

Patient 2

Progression of liver metastases had to be confirmed after 2 months by computed tomography examinations. No further therapy was given.

Patient 3

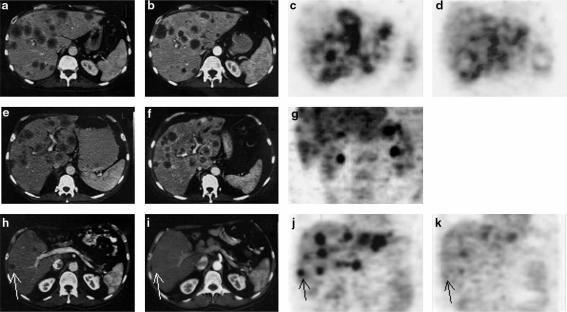

Regression of liver metastases was confirmed in computed tomography 2 months after vector administration. The size of the index lesion decreased by 38% (from 31 mm×24 mm to 22 mm×21 mm). Likewise, a major improvement was demonstrated by positron emission tomography. The therapy was continued only with gemcitabine due to the closure of the trial; after 4 months computed tomography documented further regression of the index lesion to −80% of initial size (13×12 mm), but 6 months later the patient experienced progression of disease. Data are depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3. .

Computed tomography and positron emission tomography scan examinations before and two months after administration of rAd/p53. In patient 1 (a–d), stable disease was documented after 2.5×1012 on days 2 and 3 and 23 and 24. Necrotic enhancement of the edge of the metastases (b). A slight reduction in 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose activity suggests reduced metabolic activity of metastases (d). In patient 2 (e–g), progression was revealed in CT examination, therefore, no PET scan was obtained after two months. In patient 3 (h–k), regression of liver metastasis (arrows) was confirmed in computed tomography (h,i) and a major improvement was demonstrated in positron emission tomography (j,k) after administration of the adenoviral vector.

Discussion

We conducted a phase I/II pilot trial of adenoviral transfer of wild type p53 into hepatic metastases of pancreatic carcinoma in combination with weekly gemcitabine administration. Coeliac arterial infusion of the p53-expressing replication-incompetent adenovirus derivative was well tolerated at doses resulting in therapy-associated antitumor activity. Constitutional symptoms related to vector administration consisted of fever and chills only, as has been reported in other clinical trials 30,31,32. Other side effects have been observed for blood cells and platelets, liver chemistry and the coagulation profile.

Thrombocytopenia and leukopenia occurred at a maximum around 4 d after vector administration. This early cytopenia could not be linked to the additional administration of gemcitabine as it did not recur after following cycles of gemcitabine administration, and marrow toxicity would not be expected before 8–10 d after treatment. Similar cytotoxic effects have been reported in a trial of sonographically guided intratumoral Adv.RSV-tk injection and intravenous ganciclovir for treatment of colorectal cancer metastatic to the liver 33. An immediate consumption might be expected and has been suggested because of observations from other trials and animal models. Vector administration to nonhuman primates has demonstrated a saturable and reversible decrease in platelet halflife 34,35. However, adenoviral vectors have been used to transduce platelets and megakaryocytes efficiently 36,37, and vectors expressing fibroblast growth factor 4 or thrombopoietin can significantly increase platelet counts in animal models 38,39, which strongly suggests that there is no direct inadvertent effect of adenoviral vectors on platelets. In fact, ex vivo experiments demonstrate that adenovirus does not enhance platelet aggregation upon direct interaction nor does it interfere with ADP, collagen, or epinephrine-induced platelet activation 40. Hence, the explanation as to why adenoviral vectors did induce this notable drop in platelets as reported in the trials has yet to be determined.

Patients developed laboratory signs of disseminated intravascular coagulation. According to the applied CTC criteria, increased fibrin split products or D-dimers characterize disseminated intravascular coagulation. Additionally, we noted a decline in AT III and thromboplastin time and a prolongation of partial thromboplastin time, all of which accord with activated intravascular coagulation. In spite of the altered laboratory tests and even in combination with the low platelets, none of the patients developed petechiae or other signs of bleeding disorders.

Elevation of liver enzymes and parameters of cholestasis occurred in all three patients albeit to varying degrees. Elevation of liver enzymes is common in diseases metastatic to the liver, and – therefore – their evaluation is not unequivocal. In two of our three patients, serum levels of ASAT, ALAT, GGT and bilirubin returned or nearly returned to pretreatment levels which is comparable to trials utilizing replication-incompetent and replication-selective oncolytic vectors 25,41. The elevation of liver enzymes started soon after infection and most likely indicated infection and death of hepatocytes due to viral hepatitis. Indeed, increased expression of beta 2-microglobulins and HLA-DR antigens in hepatocytes together with infiltration with CD3(+), CD4(+) and CD8(+) T-lymphocytes, resembling a mild and transient viral hepatitis after receiving adenovirus was found in animal modeling 42. Severe inflammation of the liver including death of laboratory animals was seen in other models and was dependent on the dosage of vector and on its ability to undergo replicative cycles 21,24.

A possible explanation for most of the observed phenomena could be the initial damage to endothelial and Kupffer cells. Endothelial damage and activation will subsequently activate coagulation and platelet aggregation. Recent data suggest that transduction is different for the three major cell populations composing the liver, Kupffer cells, endothelial cells and hepatocytes, with endothelial and Kupffer cells being more efficiently infected; and even clearance and sequestration of blood from adenoviral vector by Kupffer cells has been described 43,44. Interaction of viral particles with Kupffer cells could then activate the endothelium by paracrine cytokine effects 45. Notably, systemic cytokine release through inadvertent targeting of such antigen-presenting cells is probably triggered by the viral capsid proteins 46,47, and the depletion of liver from macrophages increases hepatic transgene expression and reduces the immunologic response 44. Thus, Kupffer and endothelial cell damage might be the primary event triggering a cascade of events involving injury and death of cells, the release of mediators of inflammation and immune activation. In our patients we failed to histologically detect any endothelial damage or coagulation within the smallest vessels of the liver. Endothelial damage itself has been linked to the release of cytokines which, in turn, have been reported from animal models to cause an immediate drop in blood pressure and increase in heart rate 45,48. In our patients we observed an immediate, but only slight, decrease in blood pressure in only two of three patients, while their heart rate remained constant; no supportive measures had to be taken. However, a severe systemic inflammatory response syndrome, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and multiple organ failure was observed in an 18-year old male participant in a clinical trial which finally led to the death of the patient 28. The inflammatory response to adenovirus vector administration is not restricted to the liver solely, since a varying level of inflammatory cytokine response was observed with various routes of administration including airway and myocardial administration 49 and cytokine release from mononuclear cells has been observed ex vivo46.

We saw a major improvement in a patient receiving 7.5×1012 PFU of rAd/p53 and stable disease in a patient receiving 2.5×1012 PFU on days 2, 3 and 23, 24 in combination with gemcitabine chemotherapy. Clinical trials using hepatic artery, intravenous or intratumoral infusion as the route of administration have reported antitumor activity and mild toxicity 25,26,50. In a previous trial utilizing endoscopic ultrasound-guided transgastric delivery of ONYX-015 into unresectable pancreatic carcinomas 10 of 21 patients responded to treatment in combination with gemcitabine 51, and 17 out of 23 patients had mixed tumor responses after CT-guided injection of ONYX-015 52. In a further study of administration of 4×107 to 4×1011 viral particles of a TNF-α exprssing adenovector (TNFerade) that included patients with pancreatic carcinoma, a tumor response was documented in 3 out of 6 patients 53. Only limited data is available concerning long term survival in trials utilizing p53 transfer. However, a median survival of 12 to 13 months compares favorably to a 5-month survival seen with palliative radiotherapy or paclitaxel failure in heavily pretreated patients with recurrent ovarian cancer 54.

To date, there is still limited information available on clinical trials utilizing adenoviral gene transfer strategies for metastatic pancreatic carcinoma, and few of the strategies explored in animal modelling have been evaluated for safety and efficacy in the treatment of the human disease. In summary, our study involving three patients who received a combination therapy of viral gene transfer and chemotherapy shows some potential in temporarily controlling and even diminishing tumor burden in one patient. The side effects and toxicity observed in our trial were mild and well tolerated. Further trials are warranted in an effort to improve the treatment and life expectancy of patients suffering from fatal diseases such as pancreatic carcinoma.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Dr. M. Meredyth-Stewart for careful assistance and discussion during the preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Cleary SP, Gryfe R, Guindi M, Greig P, Smith L, Mackenzie R, Strasberg S, Hanna S, Taylor B, Langer B, Gallinger S. Prognostic factors in resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma: analysis of actual 5-year survivors. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198:722–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conlon KC, Klimstra DS, Brennan MF. Long-term survival after curative resection for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Clinicopathologic analysis of 5-year survivors. Ann Surg. 1996;223:273–9. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199603000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagner M, Redaelli C, Lietz M, Seiler CA, Friess H, Buchler MW. Curative resection is the single most important factor determining outcome in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2004;91:586–94. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Apple SK, Hecht JR, Lewin DN, Jahromi SA, Grody WW, Nieberg RK. Immunohistochemical evaluation of K-ras, p53, and HER-2/neu expression in hyperplastic, dysplastic, and carcinomatous lesions of the pancreas: evidence for multistep carcinogenesis. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:123–9. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(99)90265-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Redston MS, Caldas C, Seymour AB, Hruban RH, da Costa L, Yeo CJ, Kern SE. p53 mutations in pancreatic carcinoma and evidence of common involvement of homocopolymer tracts in DNA microdeletions. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3025–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green NK, Seymour LW. Adenoviral vectors: Systemic delivery and tumor targeting. Cancer Gene Ther. 2002;9:1036–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cirielli C, Riccioni T, Yang C, Pili R, Gloe T, Chang J, Inyaku K, Passaniti A, Capogrossi MC. Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of wild-type p53 results in melanoma cell apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. Int J Cancer. 1995;63:673–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910630512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouvet M, Bold RJ, Lee J, Evans DB, Abbruzzese JL, Chiao PJ, McConkey DJ, Chandra J, Chada S, Fang B, Roth JA. Adenovirus-mediated wild-type p53 tumor suppressor gene therapy induces apoptosis and suppresses growth of human pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 1998;5:681–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02303477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cascallo M, Mercade E, Capella G, Lluis F, Fillat C, Gomez-Foix AM, Mazo A. Genetic background determines the response to adenovirus-mediated wild-type p53 expression in pancreatic tumor cells. Cancer Gene Ther. 1999;6:428–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joshi US, Dergham ST, Chen YQ, Dugan MC, Crissman JD, Vaitkevicius VK, Sarkar FH. Inhibition of pancreatic tumor cell growth in culture by p21WAF1 recombinant adenovirus. Pancreas. 1998;16:107–13. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199803000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simeone DM, Cascarelli A, Logsdon CD. Adenoviral-mediated gene transfer of a constitutively active retinoblastoma gene inhibits human pancreatic tumor cell proliferation. Surgery. 1997;122:428–33. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(97)90036-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Block A, Chen SH, Kosai K, Finegold M, Woo SL. Adenoviral-mediated herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene transfer: regression of hepatic metastasis of pancreatic tumors. Pancreas. 1997;15:25–34. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199707000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evoy D, Hirschowitz EA, Naama HA, Li XK, Crystal RG, Daly JM, Lieberman MD. In vivo adenoviral-mediated gene transfer in the treatment of pancreatic cancer. J Surg Res. 1997;69:226–31. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1997.5051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Makinen K, Loimas S, Wahlfors J, Alhava E, Janne J. Evaluation of herpes simplex thymidine kinase mediated gene therapy in experimental pancreatic cancer. J Gene Med. 2000;2:361–7. doi: 10.1002/1521-2254(200009/10)2:5<361::AID-JGM125>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oonuma M, Sunamura M, Motoi F, Fukuyama S, Shimamura H, Yamauchi J, Shibuya K, Egawa S, Hamada H, Takeda K, Matsuno S. Gene therapy for intraperitoneally disseminated pancreatic cancers by Escherichia coli uracil phosphoribosiltransferase (UPRT) gene mediated by restricted replication-competent adenoviral vectors. Int J Cancer. 2002;102:51–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenfeld ME, Vickers SM, Raben D, Wang M, Sampson L, Feng M, Jaffee E, Curiel DT. Pancreatic carcinoma cell killing via adenoviral mediated delivery of the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene. Ann Surg. 1997;225:609–18. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199705000-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sunamura M, Oonuma M, Motoi F, Abe H, Saitoh Y, Hoshida T, Ottomo S, Horii A, Matsuno S. Gene therapy for pancreatic cancer targeting the genomic alterations of tumor suppressor genes using replication-selective oncolytic adenovirus. Hum Cell. 2002;15:138–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-0774.2002.tb00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelley JR, Fraser MM, Schweinfest CW, Vournakis JN, Watson DK, Cole DJ. CaSm/gemcitabine chemo-gene therapy leads to prolonged survival in a murine model of pancreatic cancer. Surgery. 2001;130:280–8. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.115899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rochaix P, Delesque N, Esteve JP, Saint-Laurent N, Voight JJ, Vaysse N, Susini C, Buscail L. Gene therapy for pancreatic carcinoma: local and distant antitumor effects after somatostatin receptor sst2 gene transfer. Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10:995–1008. doi: 10.1089/10430349950018391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kijima H, Scanlon KJ. Ribozyme as an approach for growth suppression of human pancreatic cancer. Mol Biotechnol. 2000;14:59–72. doi: 10.1385/MB:14:1:59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Eb MM, Cramer SJ, Vergouwe Y, Schagen FH, van Krieken JH, van der Eb AJ, Rinkes IH, van de Velde CJ, Hoeben RC. Severe hepatic dysfunction after adenovirus-mediated transfer of the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene and ganciclovir administration. Gene Ther. 1998;5:451–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morral N, O'Neal WK, Rice K, Leland MM, Piedra PA, Aguilar-Cordova E, Carey KD, Beaudet AL, Langston C. Lethal toxicity, severe endothelial injury, and a threshold effect with high doses of an adenoviral vector in baboons. Hum Gene Ther. 2002;13:143–54. doi: 10.1089/10430340152712692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vasey PA, Shulman LN, Campos S, Davis J, Gore M, Johnston S, Kirn DH, O'Neill V, Siddiqui N, Seiden MV, Kaye SB. Phase I trial of intraperitoneal injection of the E1B-55-kd-gene-deleted adenovirus ONYX-015 (dl1520) given on days 1 through 5 every 3 weeks in patients with recurrent/refractory epithelial ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1562–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.6.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolkersdörfer GW, Morris JC, Ehninger G, Ramsey WJ. Trans-complementing adenoviral vectors for oncolytic therapy of malignant melanoma. J Gene Med. 2004;6:652–62. doi: 10.1002/jgm.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Habib NA, Sarraf CE, Mitry RR, Havlik R, Nicholls J, Kelly M, Vernon CC, Gueret-Wardle D, El Masry R, Salama H, Ahmed R, Michail N, Edward E, Jensen SL. E1B-deleted adenovirus (dl1520) gene therapy for patients with primary and secondary liver tumors. Hum Gene Ther. 2001;12:219–26. doi: 10.1089/10430340150218369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reid T, Galanis E, Abbruzzese J, Sze D, Wein LM, Andrews J, Randlev B, Heise C, Uprichard M, Hatfield M, Rome L, Rubin J, Kirn D. Hepatic arterial infusion of a replication-selective oncolytic adenovirus (dl1520): phase II viral, immunologic, and clinical endpoints. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6070–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carmen IH. A death in the laboratory: the politics of the Gelsinger aftermath. Mol Ther. 2001;3:425–8. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2001.0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raper SE, Chirmule N, Lee FS, Wivel NA, Bagg A, Gao GP, Wilson JM, Batshaw ML. Fatal systemic inflammatory response syndrome in a ornithine transcarbamylase deficient patient following adenoviral gene transfer. Mol Genet Metab. 2003;80:148–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2003.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wills KN, Maneval DC, Menzel P, Harris MP, Sutjipto S, Vaillancourt MT, Huang WM, Johnson DE, Anderson SC, Wen SF. Development and characterization of recombinant adenoviruses encoding human p53 for gene therapy of cancer. Hum Gene Ther. 1994;5:1079–88. doi: 10.1089/hum.1994.5.9-1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buller RE, Runnebaum IB, Karlan BY, Horowitz JA, Shahin M, Buekers T, Petrauskas S, Kreienberg R, Slamon D, Pegram M. A phase I/II trial of rAd/p53 (SCH 58500) gene replacement in recurrent ovarian cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2002;9:553–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ganly I, Kirn D, Eckhardt G, Rodriguez GI, Soutar DS, Otto R, Robertson AG, Park O, Gulley ML, Heise C, Von Hoff DD, Kaye SB, Eckhardt SG. A phase I study of Onyx-015, an E1B attenuated adenovirus, administered intratumorally to patients with recurrent head and neck cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:798–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Habib N, Salama H, Abd El Latif Abu Median A, Isac I, Abd Al Aziz RA, Sarraf C, Mitry R, Havlik R, Seth P, Hartwigsen J, Bhushan R, Nicholls J, Jensen S. Clinical trial of E1B-deleted adenovirus (dl1520) gene therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Gene Ther. 2002;9:254–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sung MW, Yeh HC, Thung SN, Schwartz ME, Mandeli JP, Chen SH, Woo SL. Intratumoral adenovirus-mediated suicide gene transfer for hepatic metastases from colorectal adenocarcinoma: results of a phase I clinical trial. Mol Ther. 2001;4:182–91. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2001.0444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolins N, Lozier J, Eggerman TL, Jones E, Aguilar-Cordova E, Vostal JG. Intravenous administration of replication-incompetent adenovirus to rhesus monkeys induces thrombocytopenia by increasing in vivo platelet clearance. Br J Haematol. 2003;123:903–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lozier JN, Csako G, Mondoro TH, Krizek DM, Metzger ME, Costello R, Vostal JG, Rick ME, Donahue RE, Morgan RA. Toxicity of a first-generation adenoviral vector in rhesus macaques. Hum Gene Ther. 2002;13:113–24. doi: 10.1089/10430340152712665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chuang JL, Schleef RR. Adenovirus-mediated expression and packaging of tissue-type plasminogen activator in megakaryocytic cells. Thromb Haemost. 2001;85:1079–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Faraday N, Rade JJ, Johns DC, Khetawat G, Noga SJ, DiPersio JF, Jin Y, Nichol JL, Haug JS, Bray PF. Ex vivo cultured megakaryocytes express functional glycoprotein IIb-IIIa receptors and are capable of adenovirus-mediated transgene expression. Blood. 1999;94:4084–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frey BM, Rafii S, Teterson M, Eaton D, Crystal RG, Moore MA. Adenovector-mediated expression of human thrombopoietin cDNA in immune-compromised mice: insights into the pathophysiology of osteomyelofibrosis. J Immunol. 1998;160:691–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sakamoto H, Ochiya T, Sato Y, Tsukamoto M, Konishi H, Saito I, Sugimura T, Terada M. Adenovirus-mediated transfer of the HST-1 (FGF4) gene induces increased levels of platelet count in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:12368–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eggerman TL, Mondoro TH, Lozier JN, Vostal JG. Adenoviral vectors do not induce, inhibit, or potentiate human platelet aggregation. Hum Gene Ther. 2002;13:125–8. doi: 10.1089/10430340152712674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reid T, Warren R, Kirn D. Intravascular adenoviral agents in cancer patients: lessons from clinical trials. Cancer Gene Ther. 2002;9:979–86. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu H, Sullivan D, Gerber MA, Dash S. Adenovirus induced acute hepatitis in non-human primates after liver-directed gene therapy. Chin Med J (Engl) 2002;115:726–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tao N, Gao GP, Parr M, Johnston J, Baradet T, Wilson JM, Barsoum J, Fawell SE. Sequestration of adenoviral vector by Kupffer cells leads to a nonlinear dose response of transduction in liver. Mol Ther. 2001;3:28–35. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schiedner G, Hertel S, Johnston M, Dries V, Van Rooijen N, Kochanek S. Selective depletion or blockade of Kupffer cells leads to enhanced and prolonged hepatic transgene expression using high-capacity adenoviral vectors. Mol Ther. 2003;7:35–43. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(02)00017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schiedner G, Bloch W, Hertel S, Johnston M, Molojavyi A, Dries V, Varga G, Van Rooijen N, Kochanek S. A hemodynamic response to intravenous adenovirus vector particles is caused by systemic Kupffer cell-mediated activation of endothelial cells. Hum Gene Ther. 2003;14:1631–41. doi: 10.1089/104303403322542275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Higginbotham JN, Seth P, Blaese RM, Ramsey WJ. The release of inflammatory cytokines from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells in vitro following exposure to adenovirus variants and capsid. Hum Gene Ther. 2002;13:129–41. doi: 10.1089/10430340152712683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schnell MA, Zhang Y, Tazelaar J, Gao GP, Yu QC, Qian R, Chen SJ, Varnavski AN, LeClair C, Raper SE, Wilson JM. Activation of innate immunity in nonhuman primates following intraportal administration of adenoviral vectors. Mol Ther. 2001;3:708–22. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2001.0330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morrissey RE, Horvath C, Snyder EA, Patrick J, Collins N, Evans E, MacDonald JS. Porcine toxicology studies of SCH 58500, an adenoviral vector for the p53 gene. Toxicol Sci. 2002;65:256–65. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/65.2.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ben Gary H, McKinney RL, Rosengart T, Lesser ML, Crystal RG. Systemic interleukin-6 responses following administration of adenovirus gene transfer vectors to humans by different routes. Mol Ther. 2002;6:287–97. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Makower D, Rozenblit A, Kaufman H, Edelman M, Lane ME, Zwiebel J, Haynes H, Wadler S. Phase II clinical trial of intralesional administration of the oncolytic adenovirus ONYX-015 in patients with hepatobiliary tumors with correlative p53 studies. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:693–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hecht JR, Bedford R, Abbruzzese JL, Lahoti S, Reid TR, Soetikno RM, Kirn DH, Freeman SM. A phase I/II trial of intratumoral endoscopic ultrasound injection of ONYX-015 with intravenous gemcitabine in unresectable pancreatic carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:555–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mulvihill S, Warren R, Venook A, Adler A, Randlev B, Heise C, Kirn D. Safety and feasibility of injection with an E1B-55 kDa gene-deleted, replication-selective adenovirus (ONYX-015) into primary carcinomas of the pancreas: a phase I trial. Gene Ther. 2001;8:308–15. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Senzer N, Mani S, Rosemurgy A, Nemunaitis J, Cunningham C, Guha C, Bayol N, Gillen M, Chu K, Rasmussen C, Rasmussen H, Kufe D, Weichselbaum R, Hanna N. TNFerade biologic, an adenovector with a radiation-inducible promoter, carrying the human tumor necrosis factor alpha gene: a phase I study in patients with solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:592–601. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Buller RE, Shahin MS, Horowitz JA, Runnebaum IB, Mahavni V, Petrauskas S, Kreienberg R, Karlan B, Slamon D, Pegram M. Long term follow-up of patients with recurrent ovarian cancer after Ad p53 gene replacement with SCH 58500. Cancer Gene Ther. 2002;9:567–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]