Abstract

In recent years, studies have suggested that accumulation of amyloid beta (Aβ) peptide in the brain plays a key role in the development of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The steady state level of Aβ peptide in the brain is determined by the rate of their production from amyloid precursor protein (APP) via β- and γ-secretases and their degradation by the activity of several enzymes. Neprilysin (NEP) appears to be the most potent Aβ peptide-degrading enzyme in the brain. Decreasing the activity of NEP (due to genetic mutations, age or diseases that alter the expression or activity of NEP) may lead to accumulation of the neurotoxic Aβ peptide in the brain; in turn this leads to neuronal loss. We investigated the efficacy of lentivirus-mediated over-expression of NEP to protect neuronal cells from Aβ peptide in vitro. Incubation of hippocampal neuronal cells (HT22) over-expressing NEP with the monomeric from of Aβ peptide decreases the toxicity of Aβ peptide on the neuronal cells, as measured through cell viability. We conclude that over-expression of NEP by a gene therapy approach in areas vulnerable to Aβ peptide aggregation in AD brain may protect the neurons from the toxicity effects of Aβ peptide and this promise a great potential target for altering the development of AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, neprilysin, amyloid beta peptide, lentiviral vectors, gene therapy, hippocampus

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that gradually damages the neurons in regions of the brain that involved in memory, learning and reasoning (Selkoe, 2001). The disease is characterized by extracellular deposition of Aβ peptide as amyloid and the presence of the intraneuronal plaques within the limbic and association cortices neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) containing paired helical filaments (PHFs) composed of hyperphosphorylated tau protein (Selkoe, 2001; Hardy and Selkoe, 2002; Forman et al., 2004). The actual mechanisms that contribute to the pathogenesis of AD are not yet known; however, accumulating evidence from a variety of genetic, pathological, biochemical and immunization studies (Selkoe, 2001; Schenk et al, 1999; Weiner et al, 2000; Bard et al, 2000) suggests that accumulation of Aβ peptide plays a central role in the development of the disease. As the disease progresses, the communications between neurons start breaking down due to the increase accumulation of neurotoxic Aβ peptide, mostly those of 40 and 42 amino acids in length (Selkoe, 2001; Iwatsubo et al., 1994; Savage et al., 1995; Yamaguchi et al.).

In an attempt to identify the pathological entity of Aβ peptide, it appears that multiple different assembly forms of Aβ peptide can be neurotoxic to neurons (Pike et al. 1993; Lambert et al.1998) and that impaired memory may be associated with the presence in the brain of soluble oligomers (Walsh et al., 2005), and perhaps, of the monomeric form that can initiate downstream changes that leading to AD. Therefore, decreasing or preventing the accumulation of monomeric form of Aβ peptide in the brain will eliminate neuronal death and memory loss. In this regards, several enzymes in the brain have been reported to degrade Aβ peptide. These enzymes include endothelin converting enzyme (ECE), insulin degrading enzyme (IDE) and neprilysin (NEP) (Eckman et al., 2001; Qui et al., 1998; Iwata et al., 2000). Among these Aβ peptide degrading enzymes, neprilysin [previously called CD10 or common acute lymphoblastic leukemia antigen (CALLA)] has been reported as the major physiological Aβ peptide-degrading enzyme in the brain (Iwata et al., 2000; Iwata et al., 2001; Shirotani et al., 2001). Unfortunately, this enzyme becomes down-regulated in areas vulnerable to Aβ peptide accumulation in the AD brain (Reilly et al., 2000; Yasojima et al., 2001; Iwata et al., 2002). Thus, upregulation of NEP activity in the brain may prevent the accumulation of Aβ peptide, protect the neurons against the toxicity of Aβ peptide, and alter the disease progression. The most direct approach is to introduce NEP directly into the brain.

Previously we reported that over-expression of NEP using a lentiviral vector in a mouse model of AD resulted in a decrease of the amyloid load in the brain (Marr et al., 2003). It is crucial that up-regulation of NEP activity be restricted to the brain, since NEP is involved in the degradation of a number of small peptides in other organs such as atrial natriuretic peptide and endothelin. Furthermore, NEP is a type-II membrane bound protein and its active site is in direct contact with the extracellular Aβ peptide and has a high affinity towards Aβ peptide compared to other small neuropeptides (Matsas et al.,1984; Shirotani et al., 2001; Iwata et al., 2005). Therefore, the overall goal of this study is to determine the feasibility of NEP gene therapy for protecting the neurons from the toxic effects of Aβ peptide.

Results

Titration of hNEP and GFP lentiviral vectors

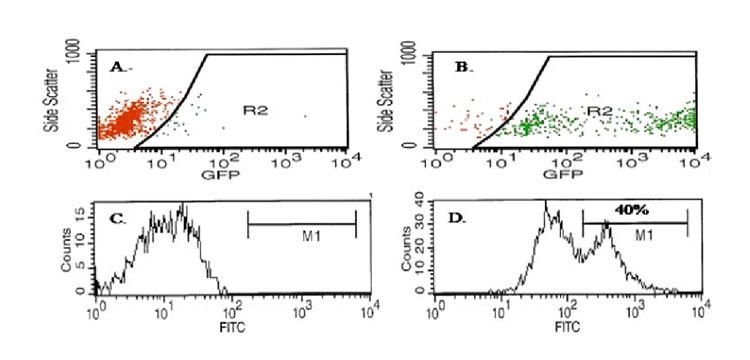

To verify that the same concentration of viral particles of lentiviral-hNEP (Lenti-hNEP) and the control lentiviral-GFP (Lenti-GFP) viruses were used for the studies, virus particles were titrated by flow cytometry. The titrations obtained for both Lenti-hNEP and Lenti-GFP viruses were 8.0×108 TU/ml (FIG.1).

FIG.1. Flow cytometry analysis of HEK 293T cells transduced with Lenti-GFP or -hNEP viruses.

Control non-transduced HEK 293T cells (A) and cells transduced with Lenti-GFP (0.1μl per well) (B) were analyzed for GFP expression by flow cytometry. Control non-transduced HEK 293T cells (C) and cells transduced with Lenti-hNEP (0.1μl per well) (D) were labeled with FITC-conjugated anti-hNEP antibody and analyzed for hNEP expression by flow cytometry.

Expression of an active hNEP in non-neuronal and neuronal cells in vitro

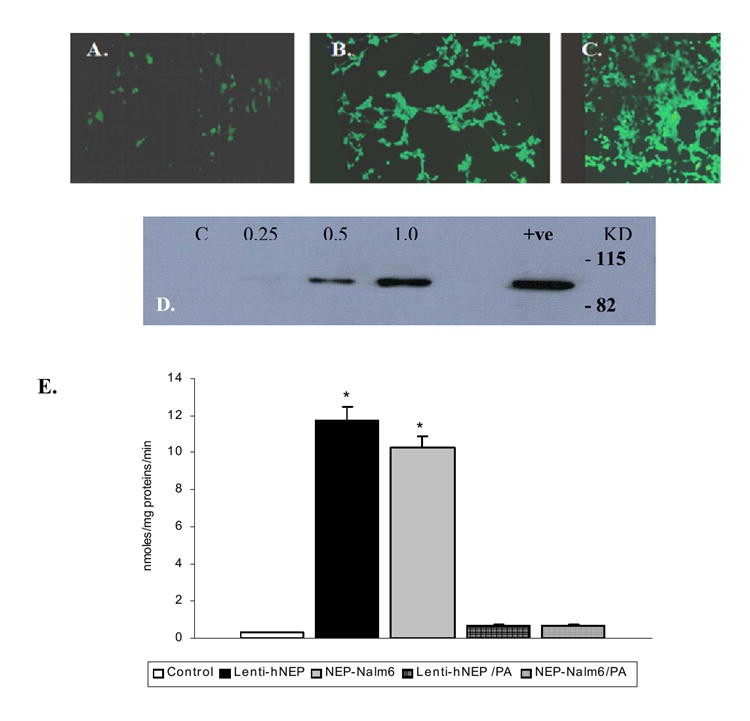

The non-neuronal HEK 293T cells were infected with Lenti-GFP or Lenti-hNEP viruses. After 48hrs, the transduced cells were either examined under the fluorescence microscope to detect the fluorescence of expressed GFP (FIG.2 A-C) or lysed to detect the expression of hNEP by immunoblot against hNEP (FIG.2D). The results show that both Lenti-hNEP and Lenti-GFP viruses were able to deliver the expression of hNEP and GFP, respectively, in a dose-dependent manner. In addition, hNEP was extracted from HEK 293T cells transduced with Lenti-hNEP viruses and found that hNEP was active and able to degrade the substrate Glutaryl-Ala-Ala-Phe-4-methoxy-2-naphthylamide (FIG.2E). The level of expression was comparable to Nalm 6 cells which express high levels of NEP based on activity measurements. This activity was inhibitable with the NEP specific inhibitor, phosphoramidon.

FIG.2. Expression of an active hNEP and GFP by lentiviral vector in non-neuronal cells.

HEK 293T cells (1.5×104 cells/well of 6-well plates) were infected with Lenti-GFP of 0.25μl (2.0× 105 TU) (A), 0.5μl (4.0× 105 TU) (B) or 1.0μl (8.0× 105 TU) (C). The fluorescence of GFP was detected by the fluorescence microscope. Immunoblot of hNEP in protein lysates (20μg) obtained from cells (1.5×104 cells/well of 6-well plates) infected with different volume (0.25, 0.5 and 1.0μl) of hNEP-L.V. (1.0μl =7.2×105 TU) as indicated in the figure (D) [C; 20μg of protein lysate of non-infected HEK 293T cells were used as a control. +ve; protein lysates from HEK 293T cells transiently transfected with hNEP were used as positive control. KD; Kilo-Dalton]. E) Protein extracts (50μg) obtained from non-transduced HEK 293T cells (control), Lenti-hNEP transduced cells (Lenti-hNEP), and human B cell precursor leukemia (Nalm6) were used to test for hNEP activity in absence and presence of phosphoramidon (PA). Nalm6 cells were used as positive control since they produce NEP endogenously in a significant amount. Values are expressed as mean ± SE (*p <0.001 compared to control or to respective protein extract +PA).

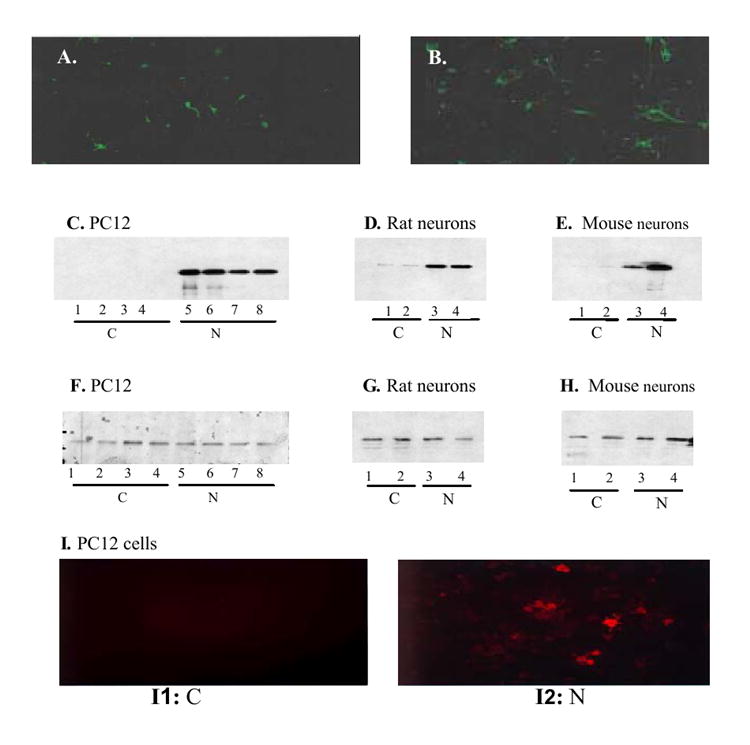

Next, primary neuronal cells were transduced with Lenti-GFP or Lenti-hNEP viruses. The expression of GFP was proportional to particles of Lenti-GFP vector used to infect mouse primary neuronal cells (FIG.3A-B), and the expression of hNEP was detected in all of the neuronal cells tested as determined by Western blot analysis for the NEP protein (FIG.3 C-E) and immunocytochemical analysis (FIG. 3I). Moreover, over-expression of hNEP by Lenti-hNEP viruses did not seem to affect the expression of proteins other than NEP, as suggested by the detection of GAPDH expression in all of the transduced neuronal cells tested (FIG.4 F-H).

FIG.3. Expression of GFP and hNEP in neuronal cells.

Mouse primary neuronal cells (5.0×105) were infected with 0.5μl (4.0×104 TU) (A) or 1.0μl (8.0×105 TU) (B) and examined under the fluorescence microscope 2-days after infection. Whole cell lysates (20μg) from initial culture of PC12 cells (5.0× 105/10 cm2 culture plate) infected with Lenti-GFP or -hNEP (1.6×106 TU) were subjected to Western blot analysis using the antibody hNEP (C) [C; control; Lenti-GFP infected cells, N; Lenti-hNEP infected cells]. D and E). Immunoblots of hNEP in whole cell lysates (20 μg) from rat (D) or mouse (E) primary neuronal cells infected with Lenti-GFP (lane 1 and 2) or Lenti-hNEP (lane 3 and 4). F-H. Duplicate blots from C-E blotted with an antibody against rat (F and G) or mouse (H) glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). I. PC12 cells infected with Lenti-GFP (I1) and Lenti-hNEP (I2) immunostained with primary mouse IgG antibody against hNEP. Rhodamine-conjugated anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody was used to detect hNEP antibody by fluorescence microscope.

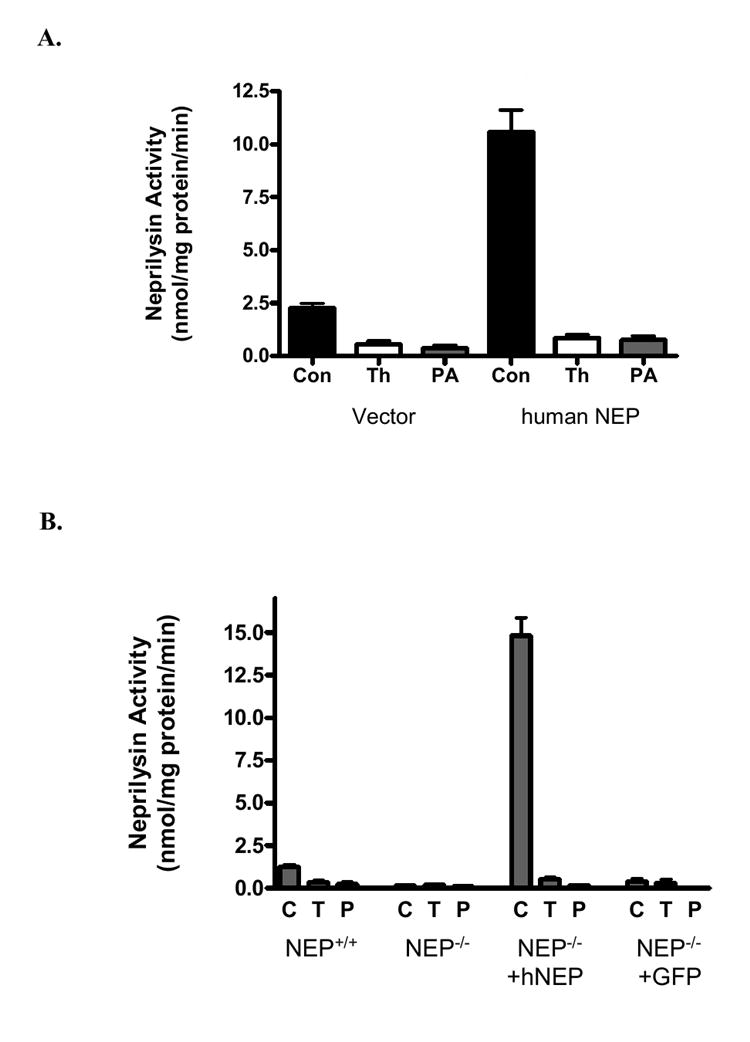

FIG.4. hNEP activity in neuronal cells.

A. Intact PC12 cells (5.0× 105) were transduced with 2.0μl (1.6 × 106 TU) of Lenti-GFP (vector) or Lenti-hNEP (human Neprilysin) and examined for neprilysin activity in absence (Con) or presence of NEP inhibitors, thiorphan (Th;T) or phosphoramidon (PA). B. hNEP activity in primary neuronal cells. NEP-/-; NEP activity in non-transduced primary neuronal cells of NEP-deficient mice. NEP-/-+hNEP; NEP activity in NEP-deficient primary neuronal cells transduced with Lenti-hNEP. NEP-/-+GFP; NEP activity in NEP-deficient primary neuronal cells transduced with Lenti-GFP. Activities were carried in absence (C) or presence of NEP inhibitors, thiorphan (T) or phosphoramidon (P). Values are expressed as mean ± SE (*p <0.0001 compared to NEP activities obtained from NEP+/+, NEP-/- or NEP-/-+GFP neuronal cells in absence of the NEP inhibitors (T and P).

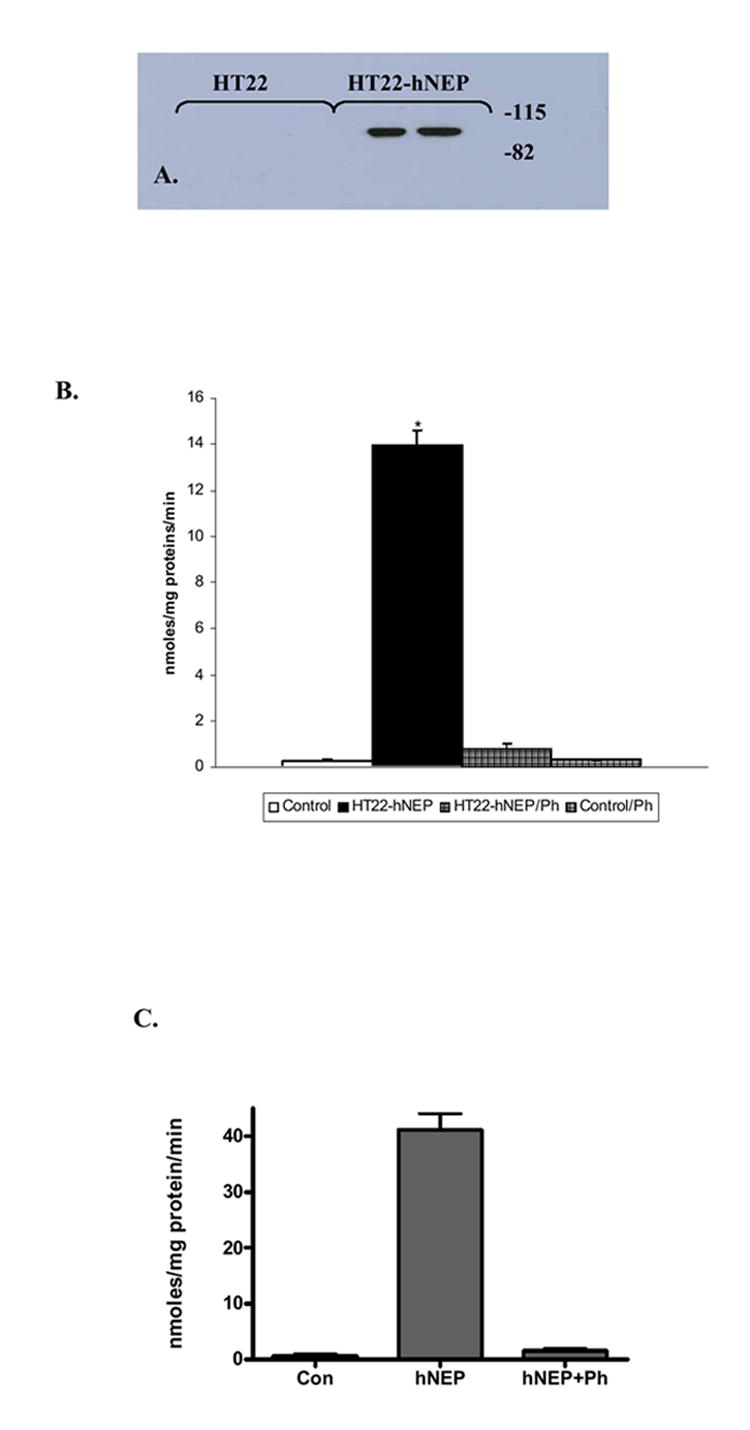

To test the activity of hNEP, PC12 cells and primary neuronal cells obtained from NEP deficient (NEP-/-) mice were infected with Lenti-GFP or Lenti-hNEP viruses. Also, primary neuronal cells from NEP wild type (NEP +/+) mice were used as a control. Protein extracts from each culture of transduced and non-transduced PC12 cells or NEP-/- primary neuronal cells as well as protein extract from NEP +/+ primary neuronal cells were tested for NEP activity using the substrate Glutaryl-Ala-Ala-Phe-4-methoxy-2-naphthylamide in absence and presence of NEP inhibitors (phosphoramidon and thiorphan). The results of these experiments indicated that Lenti-NEP viruses were also able to induce the expression of active, functional enzyme in all of neuronal cells tested (FIG.4A-B). Murine hippocampal cells (HT22) were transduced with Lenti-hNEP viruses and a cell line that stably expresses the hNEP (HT22-hNEP) was established (FIG.5A). This cell line expressed functional and active hNEP that is able to degrade the substrate Glutaryl-Ala-Ala-Phe-4-methoxy-2-naphthylamide (FIG.5B) in absence of phosphoramidon. In addition, the HT22-hNEP intact cells were incubated in the presence of Glutaryl-Ala-Ala-Phe-4-methoxy-2-naphthylamide and the activity of NEP was determined. Figure 5C shows that the intact HT22-hNEP cells can degrade the substrate very efficiently compared to control HT22 cells.

FIG.5. Immunoblot and specific activity of hNEP in HT22-hNEP cells.

Protein extracts obtained from HT22 cells transduced with Lenti-GFP and HT22-hNEP cells were used to detect the hNEP expression (20μg) by immunoblot analysis with anti-hNEP antibody (A) and to test for NEP activity (50μg) in absence or presence of phosphoramidon (PA) (B). (C) Intact HT22-hNEP cells were tested for NEP activity in the presence and absence of inhibitor (PA). Values are expressed as mean ± SE (*P<0.0001 compared to control or to respective protein extract +PA).

Degradation of Aβ peptides by hNEP

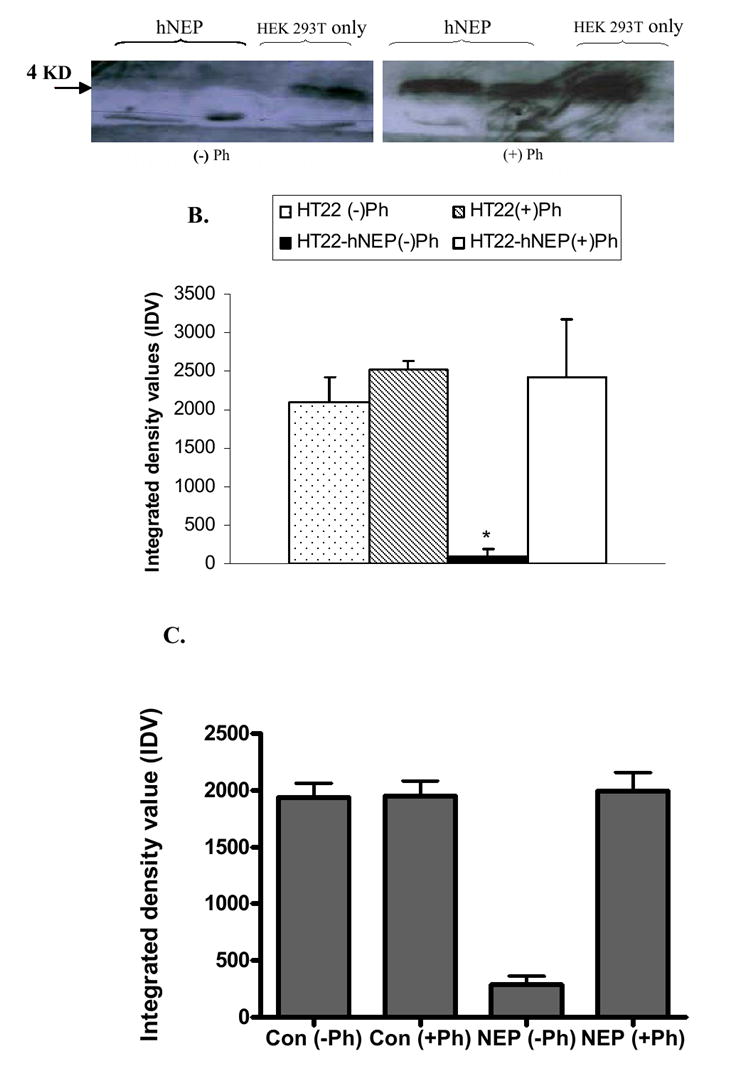

The hNEP extracts from the Lenti-hNEP transduced HEK 293T and HT22-hNEP cells were incubated with the monomeric form of Aβ peptide 1-42 or 1-40, respectively, in absence and presence of phosphoramidon. These results indicate that Lenti-hNEP was able to deliver an expression of hNEP that is able to degrade the monomeric form of Aβ peptide 1-42 and 1-40 (FIG.6 A and B). Additionally, Aβ peptide 1-42 was incubated with intact HT22 cells and the degradation capability determined (FIG. 6C). HT22-hNEP cells were very effective at degrading the Aβ1-42 peptide.

FIG.6. Degradation of Aβ peptide by hNEP.

Protein extracts (50μg) obtained from 5.0×105 non-transduced HEK 293T cells (HEK 293T only) or transduced cells with 3.6×105 TU of hNEP-L.V. (hNEP) (A) as well as protein extracts (50μg) obtained from HT22 or HT22-hNEP cells (B) were incubated with 2.5μg of Aβ peptide 1-42 (A) or Aβ peptide 1-42 monomers in absence (-) or presence (+) of phosphoramidon. (C) Intact HT22 and HT22-hNEP cells were incubated in the presence of Aβ peptide (1-42) for 4 hrs in the absence (-) or presence (+) of phosphoramidon. Aβ peptide was then precipitated from the reactions by 20%TCA and immunoblotted by Aβ peptide 1-16 antibody (10D5). Arrow indicates the size of monomer Aβ42 peptide, which is ~ 4.0 Kilo-Dalton; KD. Densitometry measurements of developed protein bands on Western blots were made using NIH image software (ImageJ 1.36b) and assigned arbitrary integrated density values (IDV). Measures are indicated as mean± SE (*P < 0.05 compared to NEP activity from HT22 or HT22-hNEP plus Ph.

Over-expression of hNEP in hippocampal cell line protects the cells against Aβ peptides toxicity

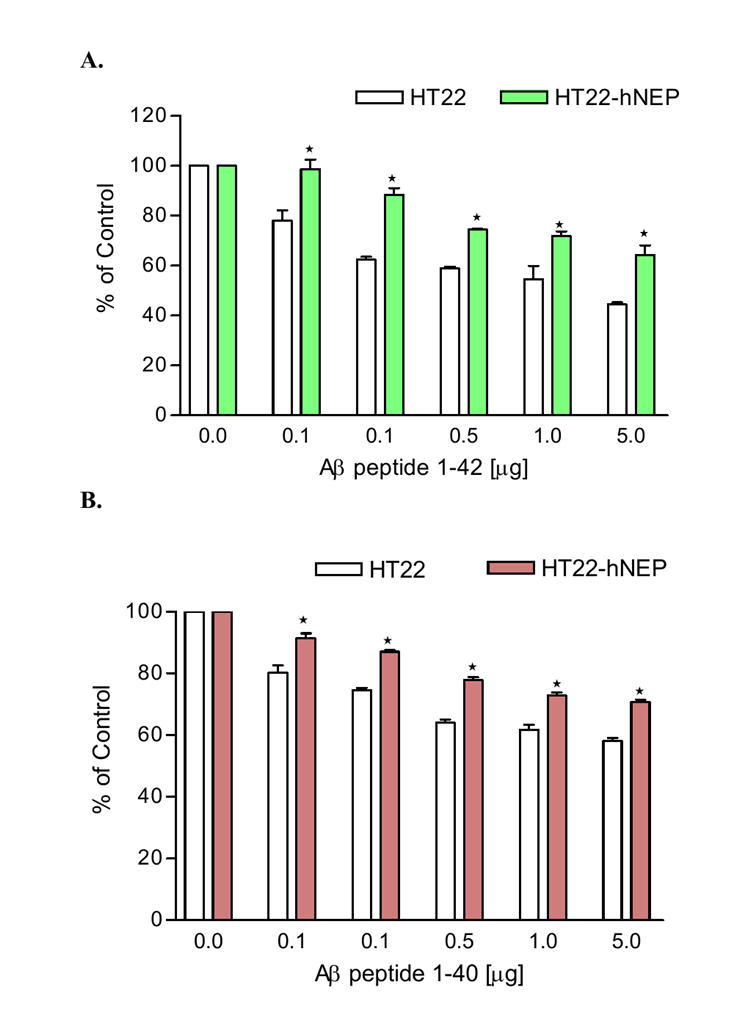

The HT22-hNEP and HT22 cells were incubated for 24hrs with DMEM media containing 1%FBS containing different concentrations of monomeric Aβ peptide (1-40 or 1-42) to investigate weather hNEP could protect the neuronal cells against Aβ peptide toxicity. At the end of the incubation period, the cell viability was quantified by the MTT assay. The results of these experiments indicate that hNEP can protect the neuronal cells from the toxicity of Aβ peptide (1-40 and 1-42) (FIG.7A-B). Specifically, the viability of neuronal cells were increased ~11-14% and ~16-26% in HT22-hNEP cells treated with different concentration of Aβ peptide 1-40 and 1-42, respectively, compared to control cells. Treatment of HT22-hNEP cells with both oligomeric Aβ peptides (1-40 and 1-42) showed no protection from cell loss (data not shown).

FIG.7. hNEP protects neuronal cells against Aβ peptides toxicity. hNEP protects neuronal cells against Aβ peptide toxicity.

HT22 and HT22-hNEP cells (3.0×103 cells/well) in 96 well plates were treated for 24hrs with 0-5.0μg as indicated in the figures of Aβ 1-42 (A) or Aβ 1-40 (B). The viability of the cells after treatment with both Aβ peptide were determined by MTT assay and results were expressed as a percentage of viable cells compared with control (untreated cells). Measure are indicated as mean± SE (*P < 0.001 compared to percentage viability of treated HT22 cells with the same concentration of Aβ peptide).

Discussion

It is generally accepted that accumulation of Aβ peptide is now considered a possible contributor to the etiology of AD. The disease is characterized by neuronal loss in areas such as hippocampus and associated cortices, which play an important role in memory. Therefore, in order to treat or prevent AD, it is necessary to lower the Aβ peptide levels in the brain to protect the neurons from the toxic effects of Aβ peptide. Several studies have focused on determining an enzyme candidate that is involved in Aβ peptide catabolism. In this regard, NEP has been reported as the dominant peptidase in regulating the level of Aβ peptide in the brain. Deficiency of NEP in NEP knock out mice resulted in defects both in the degradation of exogenously administered Aβ peptide and in the metabolic suppression of the endogenous Aβ peptide levels in a gene dose-dependent manner. In addition, both at the transcriptional and translational levels, NEP is reduced (50%) in areas vulnerable to plaque formation such as the hippocampus compared to age- matched controls. Thus, in human cases, there is substantial evidence for a causal relationship between the down-regulation of NEP and amyloid deposition.

In a previous study, we showed that introduction of NEP in the brain cells using a lentiviral vector resulted in a decrease of the Aβ peptide load in the brain. In this study, we focused on the efficacy of a gene therapeutic approach to protect the neuronal cells from the toxicity of Aβ peptide. We showed that a lentiviral vector carrying the hNEP gene was able to induce the expression of hNEP in non-neuronal and neuronal cells in vitro. The expressed hNEP was functional and able to degrade monomeric Aβ peptide and the substrate glutaryl-Ala-Ala-Phe-4-methoxy-2-naphthylamide in vitro. Moreover, HT22-hNEP cells show enhanced survival following exposure to monomeric Aβ peptide compared to control cells. Data presented here indicate that NEP does not degrade oligomeric Aβ peptide and does not protect neuronal cells from the oligomeric form of Aβ. Previous studies have demonstrated some degradation and small protective effects against the Aβ oligomeric form however the data can be interpreted differently (Iwata et al., 2000; Shirotani et al., 2001; Kanemitsu et al., 2003; Mazur-Kolecka and Frackowiak, 2006; Huang et al., 2006). We believe that because of the dynamic nature of the Aβ peptide and its ability to oscillate between monomeric and oligomeric states neprilysin will degrade the monomeric peptide and reduce the oligomeric form. This will appear as an activity in the degradation of oligomeric Aβ peptides, but in fact does not.

Our data further establishes neprilysin as a major factor in the pathogenesis of AD. Alterations in neprilysin expression or activity will affect the development and progression of AD and therapies to enhance neprilysin activity may postpone the onset or expression of the disease. Gene therapy may be only one approach to treating AD and further studies to understand the mechanisms and pathogenesis are essential.

Experimental Procedures

Cell Culture and Medium

Murine hippocampal cell line

HT22 cells (gift from D. Schubert, Salk Institute, San Diego, California), which are an immortalized murine hippocampal cell line, were maintained in DMEM (high glucose) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone, Logan, UT) and 100 unit/ml penicillin plus 100μg/ml streptomycin (P/S) (invitrogen) at 37°C in 5% CO2 incubator.

Rat neuronal-like cell line

PC12 cells, which are rat pheochromocytoma were maintained in F-12K medium (invitrogen) with 15% heat-inactivated horse serum (Hyclone) and 2.5% FBS (Hyclone) plus antibiotics (P/S) at 37°C in 5% CO2 incubator.

Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells

HEK 293T cells were cultured in DMEM (high glucose) (invitrogen) plus 10% FBS (Hyclone) and antibiotics (P/S) at 37°C in 5% CO2 incubator.

Human B cell leukemia cell line (Nalm6)

The cells were purchased from the DSMZ-German collection of microorganisms and cell cultures (Braunschweig, Germany). The cells were maintained in 90% RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen) containig 10% FBS and antibiotic (P/S) (invitrogen) at 37°C in 5% CO2 incubator. These cells were shown to express an active functional NEP (CD10 or CALLA) (Hurwitz et al., 1979; Shipp et al., 1989) and in this study were used as a positive control for NEP activity experiments.

Rat and Mouse primary cerebral cortical and hippocampal neurons

Cortical and hippocampal neurons were prepared from embryonic day 18 of Sprague-Dawley rat (Harlan, Indianapolis, Indiana), wild type (C57) mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) and NEP-null (NEP-/-) mice embryo. In brief, the cerebral cortexes and hippocampi were dissected and harvested under the dual view stereomicroscope microscope (Motic Instruments Inc.). The cortices and hippocampi were cut into small pieces using a sterile scissor followed by treatment with 10ml of 0.25 g/ml trypsin (invitrogen) for 10min at 37°C. Trypsinzed tissues were then gently pipetted up and down with Pasteur pipette to obtain a single neuronal cell suspension. Then, cells were washed three times with 10ml of Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) plus 10mg/L of gentamicin. Thereafter, cells were counted and cultured in poly-D-lysine coated 6-well or 10cm2 culture plates at density of 1×105 cells/cm2 in neurobasal media (Invitrogen) containing 500μM glutamine and B-27 supplement (Invitrogen).

Lentiviral vector production

Vector plasmids were constructed for the production of third generation lentiviral vectors that express separately the human neprilysin gene (Lenti-hNEP) or the green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene (Lenti-GFP) as a control as described previously (Marr et al.,2003; Miyoshi et al., 1998; Dull et al., 1998). Briefly, HEK 293T cells were transfected with vector and packaging plasmids, the supernatants were collected, and vectors were concentrated by centrifugation. The lentiviral vector titers were estimated by flow cytometry (below).

Flow cytometry

HEK 293T cells were counted and plated into 6-well plates before infection. Infection of the cells was done by incubating the cells with serial dilutions of the lentiviral vector preparation in culture medium (500μl) overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2 incubator. The next day the transduced cells were washed with fresh medium and incubated for 3 day to allow the expression of transgenes. The transduced cells were then detached from the culture plates with an EDTA buffer and washed twice with ice-cold PBS buffer. The pellets of cells that infected with Lenti-NEP vector were resuspended in 0.5ml of PBS buffer containing 10μl of FITC-conjugated mouse anti-human CD10 antibody (Chemicon) and incubated for 1hr at 4°C. Then, the cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS buffer and analyzed by flow cytometry. The pellets of cells transduced with Lenti-GFP vector were simply resuspended in 0.5ml of ice-cold PBS buffer and directly analyzed by flow cytometry. The percentage of cells positive was used to determine the number of transducing units per unit volume.

Establishing HT22-hNEP stable cell line

8.0×105 HT22 cells cultured for 24hrs in 10 cm2 culture plates were infected with 1.0μl (8.0×105 TU) of Lenti-hNEP vector in a final volume of 5.0ml culture media. After 24hrs of infection at 37 °C in 5% CO2 incubator, the growth media were replaced with fresh culture media and cells let to grow for 3 days. Thereafter, transduced cells were detached from the cultures plates by an EDTA buffer followed by resuspending the cells (1.0×107) in 0.5ml PBS buffer containing 10μl mouse anti-human CD10 antibody (DakoCytomation, Inc., Carpinteria, CA) for 1.0hr at 4°C. After washing the cells twice with ice-cold PBS buffer, cells expressing hNEP and labeled with the anti-hNEP antibody were sorted using goat anti-mouse IgG microbeads antibody and MiniMACS magnetic isolation system (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) according to the manufacturer.

Immunocytochemistry staining

PC12 cells (2.0× 104 cells) were cultured in 2-well Lab-Tek glass chamber slide (Nalge Nunc, Naperville, IL) coated with poly-D-lysine. Then, cells were separately infected with 0.25μl (~1.8×105 TU) of Lenti-hNEP or Lenti-GFP vector. After 2 days of transduction, cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS buffer followed by fixation with 0.5ml 4.0% paraformaldehyde (prepared in PBS buffer) for 20 minutes at room temperature. Then, cells were washed twice with 1.0ml of PBS buffer and blocked for 1.0hr at room temperature with 0.5ml of 0.1% BSA and 10% FBS in PBS buffer. After incubating the cells with the primary mouse anti-human CD10 antibody (M0727, 1:100 dilution, DAKO) for 1.0hr, the sheep anti-mouse IgG Rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibody (AP300R, dilution 1:10, Chemicon) was used to detect anti-human CD10 antibody by florescence microscope at excitation/emission wavelengths of 550/570 nm.

Aβ peptide preparation

Aβ peptide (1-40 and 1-42) was purchased from Biosource International (Camarillo, California). The batches of peptide were dissolved to 1mM in 1, 1, 1, 3, 3, 3-hexafluro-2-propanol (HFIP) (Sigma) to break any pre-existing aggregates. Hexafluoroisopropanol was removed by lyophilization, and the peptide films were dissolved to 5mM in DMSO and stored at -20 °C mainly as monomer stocks as described previously (Dahlgren et al., 2002).

Aβ peptide degradation assay

Protein extracts (40μg) from HEK 293T and Lenti-hNEP transduced HEK 293T cells were incubated with 2.5μg of the monomeric form Aβ peptide 1-40. Also HT22 and HT22-NEP cells were incubated with 2.5μg of the monomeric form Aβ peptide 1-42 in a final volume of 100μl of 50mM HEPES buffer (pH: 7.2) at 37°C for 4hrs. In addition, 10 μM Aβ peptide (1-42) was incubated with intact HEK 293T cells in culture for 4 hrs in 6 well dishes at 1 × 106 cells/plate. The reactions were carried in absence and presence of the NEP inhibitor phosphoramidon (Sigma). Then, proteins and peptides in the reaction were precipitated using equal volume of 20% of TCA (trichloroacetic acid). All pellets were resuspended in 1X SDS protein loading buffer followed by analyses with WB against Aβ peptide (below). For oligomeric studies, Aβ peptide was incubated for 24 hours at 37°C and the degree of oligomerization was determined by Western blot analysis.

Immunoblots

To detect the expression of NEP in vitro, cells transduced with Lenti-hNEP or Lenti-GFP vector were washed twice with ice-cold PBS buffer followed by lysing the cells with HEPES lysis buffer [50mM HEPES, 100mM NaCl, and 1.0% Triton 100-X (pH: 6.5), plus protease inhibitors (1.0μg/ml pepstatin-A and 1.0μg/ml leupeptin; Sigma)], for 1.0hr at 4°C . The lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE on a 5-10% gradient Tris-acetate polyacrylamide gel. Immunoblots were performed with a mouse anti-human CD10 antibody (1:100,1hr) (DakoCytomation, Inc., Carpinteria, CA) or mouse anti-human CD10 antigen (CALLA) (1:1000, 1hr) (Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA) and a secondary goat anti-mouse-IgG-HRP antibody (1:1000, 1 hr) (Zymed Laboratories Inc., San Francisco, CA) and visualized by chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ).

To detect Aβ peptide degradation by hNEP in vitro, all TCA-precipitates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE on 10-20% gradient Tris-acetate polyacrylamide gel. Immunoblots were performed with mouse anti human Aβ peptide primary antibody (10D5, Athena neurosciences, Worcester, Massachusetts) (1:1000, 1hr) and a secondary goat anti-mouse-IgG-HRP antibody (1:1000, 1 hr) (Zymed Laboratories Inc., San Francisco, CA) and visualized by chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). To detect the mouse and rat glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) (1/5000, 1 hr).

Neprilysin activity assay

Neprilysin activity was measured as described previously (Li and Hersh, 1995). Briefly, proteins in whole cell lysates were quantified using the BCA reaction. Then, 50μg protein of whole cell lysates were separately incubates with glutaryl-Ala-Ala-Phe-4-methoxy-2-naphthylamide as a substrate. Further incubation with leucine aminopeptidase released free 4-methoxy-2-naphthylamide that was measured fluorometrically at an emission the proteins wavelength of 425nm. For the inhibition study were preincubated with 10 μM or 10 μM thiorphan phosphoramidon for 5 min before the addition of the substrate. For PC-12 cell studies, intact cells were incubated with glutaryl-Ala-Ala-Phe-4-methoxy-2-naphthylamide and then the media was incubated with leucine aminopeptidase and measured fluorometrically as described above.

Cell Toxicity Assay

HT22 and HT22-hNEP cells were cultured in 96-well plates at a density of 3000 cells/well in a complete culture media for 24hrs. Then, growth media was replaced with fresh culture media (100μl/well) containing 1.0% FBS and different concentration (50ng -5μg) of Aβ peptides 1-40 or 1-42 monomers. After 24hrs, MTT assay was performed by adding 20μl of 5.0 mg/ml of MTT (3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazolyl-2)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) (Sigma) to all wells. The plates were then incubated for 4hrs at 37°C in 5% CO2 incubator. Media was then removed by aspiration, 200 μl of DMSO was added, and the formazan crystals solubilized with continuous agitation at room temperature. Optical density (OD) measurements were taken at 550 and the difference in OD relative to untreated controls was taken as a measure of cell viability. The percentage of cell viability was calculated by comparing the OD at 550 nm of the wells treated with Aβ peptides with that of the Aβ peptides-free control based on the following equation [OD550 of wells that contained the Aβ peptides /OD550 of the Aβ peptides-free (control) well) × 100%].

Statistical analysis

Multiple comparison of the activities, integrated density values and % of cell viability were analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test.

Acknowledgments

NIH grant AG019323 (MSK) and VA Merit Review (MSK)

Abbreviations

- hNEP

human neprilysin

- Aβ peptide

amyloid beta peptide

- lenti

lentiviral

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Section: 8. Disease Related Neuroscience

References

- Bard F, Cannon C, Barbour R, Burke RL, Games D, Grajeda H, Guido T, Hu K, Huang J, Johnson-Wood K, Khan K, Kholodenko D, Lee M, Lieberburg I, Motter R, Nguyen M, Soriano F, Vasquez N, Weiss K, Welch B, Seubert P, Schenk D, Yednock T. Peripherally administered antibodies against amyloid ß-peptide enter the central nervous system and reduce pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Nat Med. 2000;6:916–919. doi: 10.1038/78682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlgren KN, Manelli AM, Stine WB, Jr, Baker LK, Krafft GA, LaDu MJ. Oligomeric and fibrillar species of amyloid-beta peptides differentially affect neuronal viability. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:32046–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201750200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dull T, Zufferey R, Kelly M, Mandel RJ, Nguyen M, Trono D, Naldini L. A third-generation lentivirus vector with a conditional packaging system. J Virol. 1998;72:8463–71. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.8463-8471.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckman EA, Reed DK, Eckman CB. Degradation of the Alzheimer’s amyloid beta peptide by endothelin-converting enzyme. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:24540–24548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007579200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman MS, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Neurodegenerative diseases: a decade of discoveries paves the way for therapeutic breakthroughs. Nat Med. 2004;10:1055–1063. doi: 10.1038/nm1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurwitz R, Hozier J, LeBien T, Minowada J, Gajl-Peczalska K, Kubonishi I, Kersey J. Characterization of a leukemic cell line of the pre-B phenotype. Int J Cancer. 1979;23:174–180. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910230206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata N, Tsubuki S, Takaki Y, Watanabe K, Sekiguchi M, Hosoki E, Kawashima-Morishima M, Lee HJ, Hama E, Sekine-Aizawa Y, Saido TC. Identification of the major Aβ1–42-degrading catabolic pathway in brain parenchyma: suppression leads to biochemical and pathological deposition. Nat Med. 2000;6:143–150. doi: 10.1038/72237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata N, Tsubuki S, Takaki Y, Shirotani K, Lu B, Gerard NP, Gerard C, Hama E, Lee HJ, Saido TC. Metabolic regulation of brain Aβ by neprilysin. Science. 2001;292:1550–1552. doi: 10.1126/science.1059946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwatsubo T, Odaka A, Suzuki N, Mizusawa H, Nukina N, Ihara Y. Visualization of Abeta 42(43) and Abeta 40 in senile plaques with end-specific Abeta monoclonals: evidence that an initially deposited species is A beta 42(43) Neuron. 1994;13:45–53. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90458-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata N, Takaki Y, Fukami S, Tsubuki S, Saido TC. Region-specific reduction of Abeta-degrading endopeptidase, neprilysin, in mouse hippocampus upon aging. J Neurosci Res. 2002;70:493–500. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata N, Higuchi M, Saido TC. Metabolism of amyloid-beta peptide and Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacol Ther. 2005;108:129–48. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanemitsu H, Tomiyaya T, Mori H. Human neprilysin is capable of degrading amyloid b peptide not only in the monomeric but also the pathological oligomeric form. Neurosci Lett. 2003;350:113–116. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00898-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MP, Barlow AK, Chromy BA, Edwards C, Freed R, Liosatos M, Morgan TE, Rozovsky I, Trommer B, Viola KL, Wals P, Zhang C, Finch CE, Krafft GA, Klein WL. Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Abeta1-42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6448–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Hersh LB. Neprilysin: assay methods, purification, and characterization. Methods Enzymol. 1995;248:253–263. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)48018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marr RA, Rockenstein E, Mukherjee A, Kindy MS, Hersh LB, Gage FH, Verma IM, Masliah E. Neprilysin gene transfer reduces human amyloid pathology in transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1992–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-01992.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsas R, Kenny AJ, Turner AJ. The metabolism of neuropeptides. The hydrolysis of peptides, including enkephalins, tachykinins and their analogues, by endopeptidase-24.11. Biochem J. 1984;223:433–440. doi: 10.1042/bj2230433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi H, Blomer U, Takahashi M, Gage FH, Verma IM. Development of a self-inactivating lentivirus vector. J Virol. 1998;72:8150–7. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.8150-8157.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike CJ, Burdick D, Walencewicz AJ, Glabe CG, Cotman CW. Neurodegeneration induced by beta-amyloid peptides in vitro: the role of peptide assembly state. J Neurosci. 1993;13:1676–87. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-04-01676.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu WQ, Walsh DM, Ye Z, Vekrellis K, Zhang J, Podlisny MB, Rosner MR, Safavi A, Hersh LB, Selkoe DJ. Insulin-degrading enzyme regulates extracellular levels of amyloid beta-protein by degradation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32730–32738. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly CE. Neprilysin content is reduced in Alzheimer brain areas. J Neurol. 2001;248:159–60. doi: 10.1007/s004150170259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage MJ, Kawooya JK, Pinsker LR, Emmons TL, Mistretta S, Siman R, Greenberg BD. Elevated Aβ levels in Alzheimer’s disease brain are associated with selective accumulation of Aβ42 in parenchymal amyloid plaques and both Aβ40 and Aβ42 in cerebrovascular deposits. Amyloid Int J Exp Clin Invest. 1995;2:234–240. [Google Scholar]

- Schenk D, Barbour R, Dunn W, Gordon G, Grajeda H, Guido T, Hu K, Huang J, Johnson-Wood K, Khan K, Kholodenko D, Lee M, Liao Z, Lieberburg I, Motter R, Mutter L, Soriano F, Shopp G, Vasquez N, Vendevert C, Walker S, Wogulis M, Yednock T, Games D, Seubert P. Immunization with amyloid-ß attenuates Alzheimer-disease-like pathology in the PDAPP mouse. Nature. 1999;400:173–177. doi: 10.1038/22124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirotani K, Tsubuki S, Iwata N, Takaki Y, Harigaya W, Maruyama K, Kiryu-Seo S, Kiyama H, Iwata H, Tomita T, Iwatsubo T, Saido TC. Neprilysin degrades both amyloid beta peptides 1-40 and 1-42 most rapidly and efficiently among thiorphan- and phosphoramidon-sensitive endopeptidases. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:21895–901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008511200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipp MA, Vijayaraghavan J, Schmidt EV, Masteller EL, D’Adamio L, Hersh LB, Reinherz EL. Common acute lymphoblastic leukemia antigen (CALLA) is active neutral endopeptidase 24.11 (“enkephalinase”): direct evidence by cDNA transfection analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:297–301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.1.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer’s disease: genes, proteins, and therapy. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:741–766. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Shankar GM, Townsend M, Fadeeva JV, Betts V, Podlisny MB, Cleary JP, Ashe KH, Rowan MJ, Selkoe DJ. The role of cell-derived oligomers of Abeta in Alzheimer’s disease and avenues for therapeutic intervention. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33:1087–90. doi: 10.1042/BST20051087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner HL, Lemere CA, Maron R, Spooner ET, Grenfell TJ, Mori C, Issazadeh S, Hancock WW, Selkoe DJ. Nasal administration of amyloid-ß peptide decreases cerebral amyloid burden in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2000;48:567–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi H, Sugihara S, Ishiguro K, Takashima A, Hirai S. Immunohistochemical analysis of COOH-termini of amyloid beta protein (Aβ) using end-specific antisera for Aβ40 and Aβ42 in Alzheimer’s disease and normal aging. Amyloid: Int J Exp Clin Invest. 1995;2:7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Yasojima K, McGeer EG, McGeer PL. Relationship between beta amyloid peptide generating molecules and neprilysin in Alzheimer disease and normal brain. Brain Res. 2001;919:115–21. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]