Abstract

Background

People with learning disabilities are more prone to a wide range of additional physical and mental health problems than the general population. This paper seeks to map the issues and review the evidence on access to healthcare for these patients. The review aimed to identify theory, evidence and gaps in knowledge relating to the help-seeking behaviour of people with learning disabilities and their carers; barriers and problems they experience accessing the full range of health services; and practical and effective interventions aiming to improve access to healthcare.

Methods

A three strand approach was adopted, including searches of electronic databases, a consultation exercise, and a mail shot to researchers and learning disability health professionals. Evidence relevant to our model of ‘access’ was evaluated for scientific rigour and selected papers synthesised.

Findings

Overall, a lack of rigorous research in this area was noted and significant gaps in the evidence base were apparent. Evidence was identified on the difficulties identifying health needs among people with learning disabilities and the potentially empowering or obstructive influence of third parties on access to healthcare. Barriers to access identified within health services included problems with communication, inadequate facilities or rigid procedures, and lack of interpersonal skills amongst mainstream health professionals in caring for these patients. A number of innovations designed to improve access were identified, including a communication aid, a prompt card to support general practitioners, health check programmes and walk-in clinics. However the effectiveness of these strategies in improving access to appropriate healthcare remains to be established.

Introduction

This review examines the evidence on access to healthcare for people with learning disabilities. What is understood by the label learning disability* is likely to vary across sociocultural groups. Few people are identified as ‘learning disabled’ at birth. In Western cultures the label is often acquired during school years when intellectual development deviates from current concepts or definitions of what is ‘normal’. ‘Learning disability’ is therefore a label prescribed by the culture in which a person resides. The term ‘learning disability’ is used in this review refers to significant intellectual impairment and deficits in social functioning or adaptive behaviour (basic everyday skills) that have been present from childhood 1.

UK prevalence of learning disability, based on this definition, has been estimated at 230,000 to 350,000 people with severe learning disabilities, and 580,000 to 1,750,000 people with mild learning disabilities 1. People with severe learning disabilities are reliant on carers to assist them with daily living and are almost certainly known to statutory service providers. People with mild learning disabilities may not be known to service providers. The stigma attached to the label acts as a strong disincentive to seek assistance for those able to manage their lives without outside intervention. This paper addresses the experience of people known to statutory services who include a significant, but relatively small number of people with milder levels of learning disabilities and all those with moderate, severe and profound learning disabilities.

People with learning disabilities are more prone to a wide range of additional physical and mental health problems than the general population. For example, it is well-established that people with Downs syndrome have increased risks of heart problems and hypothyroidism and that incidence of health problems increases with severity of disability2 4. There is evidence that the health problems of people with learning disabilities are often unrecognised and therefore untreated (e.g. 2 3 ).

The closure of long-stay hospitals for people with learning disabilities has generated new demands on mainstream NHS services to provide appropriate healthcare for this group. Current NHS policies5 6 emphasise the provision of equitable health services to the whole population of England. Similarly, policy for learning disability services7 stresses that these patients should make full use of mainstream services (with appropriate support).

It is therefore important to establish whether people with learning disabilities living in the community can successfully access mainstream health services, the barriers to doing so and initiatives to overcome them. The authors were funded to consult stakeholders and review relevant literature to ascertain the extent of current knowledge.

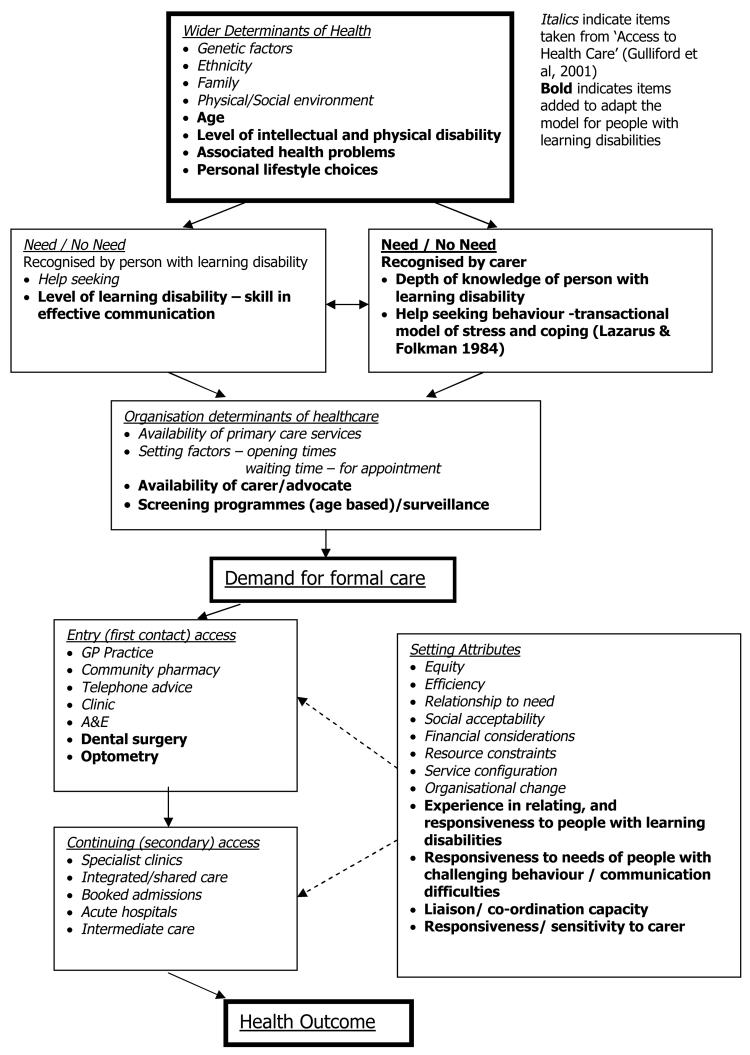

The definition of ‘access’ adopted for the review draws on that outlined in ‘Access to Health Care’ 8, which broadly explores the issues in accessing health services. The term ‘access’ is often used in two ways, to ‘have access’ where a physically accessible service exists, and to ‘gain access’ where a service is successfully used. Gulliford et al developed a model to illustrate the interaction between factors affecting access to healthcare8. Evidence on unmet need indicated people with learning disabilities have difficulty identifying signs or symptoms requiring medical attention, forcing them to rely on family or paid carers. The model was adapted to take these additional factors for people with learning disabilities into account (see Figure 1) and provided the conceptual framework for the literature review.

Figure 1. Access to Health Care for People with Learning Disabilities.

Figure 1 describes factors that affect ‘access’ to healthcare for people with learning disabilities:

Wider Determinants of Health include personal characteristics, such as genetic make up or age, aspects of an individual's physical or social environment, and personal lifestyle choices.

Identification of Need is the impetus for accessing health services. Learning disabilities affect individuals' capacities to recognise and communicate health status. Access depends therefore, to a greater or lesser extent, on the skills of a third party in recognising/interpreting the person's behaviour as indicating distress or illness.

-

Organisation of healthcare determines whether individuals ‘have access’ to services, that is, the availability of appropriate services to meet wide ranging personal circumstances. Unlike the general population, however, third parties constitute an additional factor in enabling access to services for people with learning disabilities as they are likely to be involved in obtaining appointments; providing escort or transport; and facilitating communication with health professionals.

Access to regular health screening/surveillance is important to ensure appropriate access to both primary and secondary healthcare for this group, particularly where their disability carries associated risks of certain illnesses. For example, hypothyroidism is known to be more prevalent in people with Down's syndrome9.

Entry (First contact) healthcare services are those to which individuals may refer themselves and require no professional assessment to determine access. These are the most frequently accessed services and provide a ‘gateway’ through which people may ‘gain access’ to secondary or ‘continuing’ health services. Their role as both service providers and ‘gatekeepers’ means that they are of particular importance when considering access issues.

Continuing healthcare is usually provided on referral from a health professional. The long-term health problems experienced by many people with learning disabilities mean that they are more likely to use these services than non-disabled patients. Health professionals themselves are therefore more likely to be involved in detecting additional symptoms and problems, and making referrals to other services.

Recognising that successful access to services for people with learning disabilities may depend on novel approaches to healthcare provision, the review also covered evidence on interventions aimed at improving access to healthcare for this group.

Aims

The formal aims of the review were to identify theory, evidence and gaps in knowledge relating to:

the help-seeking behaviour of people with learning disabilities and their carers;

barriers and problems people with learning disabilities experience in accessing the full range of health services;

practical and effective interventions that aim to improve access to healthcare.

Methods

Established methods for conducting literature reviews were used as a source of best practice, and adapted to the needs of the diffuse and multi-dimensional topic of ‘access’33. A three strand approach was adopted to ensure the issues were comprehensively addressed including:

1) searches of electronic bibliographic databases; 2) a consultation exercise; and 3) a mail shot to researchers in the field and learning disability health professionals.

Broad inclusion/exclusion criteria for searching initially set included: English language literature published from 1980 onwards; from countries that have a similar health service system to the UK; relating to people with learning disabilities of any age; using any study design; and covering one or more dimension of the access model.

1) Bibliographic database searches

Searching used both natural language and thesaurus approaches to identify relevant literature. This allowed for inconsistencies in the indexing practices of bibliographic databases whilst balancing the need for sensitivity and specificity. The electronic databases, libraries and websites searched are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Electronic databases, libraries and websites searched.

| AgeInfo; |

| ASLIB; |

| ASSIA; |

| BEI; |

| CareData; |

| CINAHL; |

| Cochrane Library; |

| Down's Syndrome Association; |

| Embase; |

| ERIC; |

| HMIC; |

| IBSS; |

| ISI; |

| Medline; |

| PsychInfo; |

| RADAR; |

| Royal College of Nursing library; |

| Royal National Institute for the Blind library; |

| SCOPE; |

| SIGLE; |

| Social Science Citation Index; |

| Sociological Abstracts; |

Copies of search strategies are available from authors on request.

Additional references were also identified by checking the citations of relevant papers (snowballing). However, ‘snowballing’ only began in the later stages of the project, once critical appraisal and evaluation had begun, and therefore their full text was only obtained if it was easily accessible.

2) Consultation

Literature searching was supplemented by a consultation exercise to map the issues important in access to healthcare for people with learning disabilities. This comprised two main elements: i) Consultations with representatives of national organisations of and for people with learning disabilities and experts in the field; ii) Discussion groups with people with learning disabilities and family and paid carers. These consultations helped to refine terms for further literature searching, inter alia highlighting gaps where research is needed.

3) Mail shot

A mail shot to researchers and learning disability health professionals was used to obtain literature that would be difficult to identify through electronic databases. In total 300 contacts were made and 57 people supplied information for consideration. Ten of these publications were considered potentially relevant to the model guiding the review.

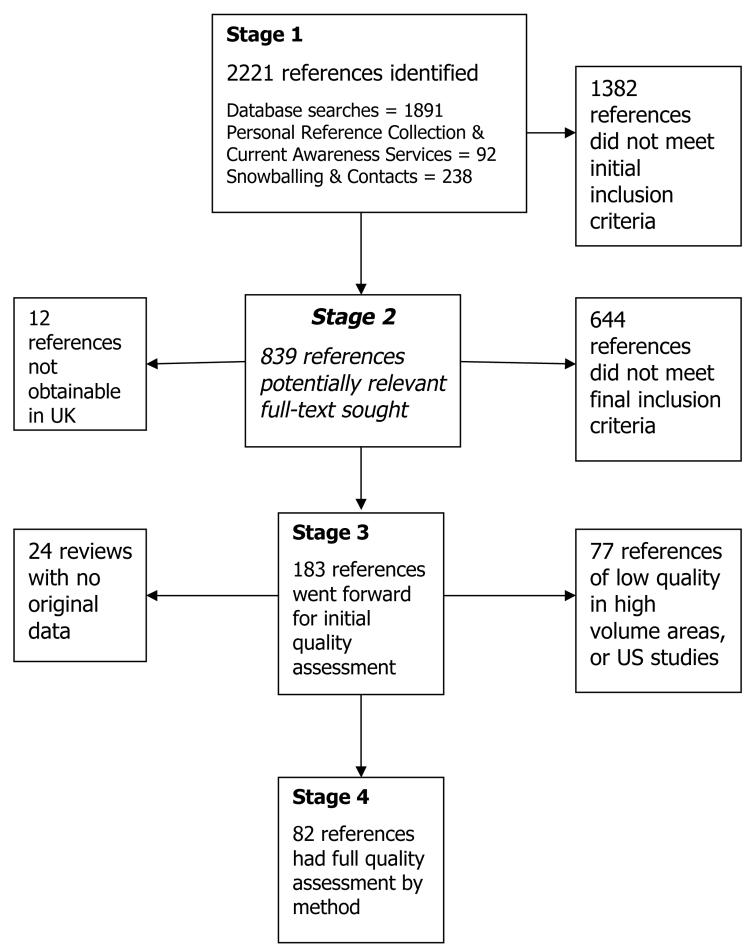

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

The concept of ‘funnelling’ 10 was adopted to identify the core set of relevant publications to include in the review. Initial inclusion/exclusion criteria were continually refined in response to issues arising from the identified literature and comments from people consulted. A flow chart showing the progress of the 2221 references identified through the funnelling process is included in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Stages of funnelling process.

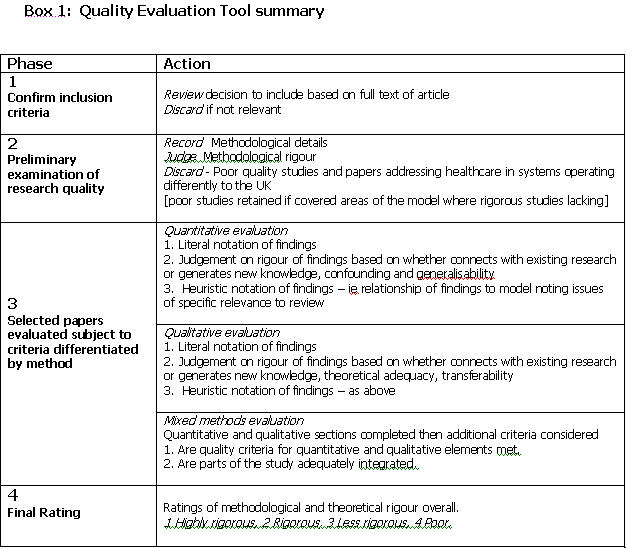

Evaluation

A tool to evaluate quality was devised, based on the work of methodological researchers such as Noblit & Hare11, and criteria proposed by the Health Care Practice Research and Development Unit, University of Salford12. There is some agreement amongst researchers about the most important indicators of methodological and epistemological quality, many of which may be applied to both quantitative and qualitative research. As the literature around access to healthcare is diverse in its methodology, a flexible quality evaluation tool was designed capable of adapting to this diversity by employing specific criteria depending on whether the study had a quantitative, qualitative or mixed method focus (see Box 1).

Box 1: Quality Evaluation Tool summary.

Eighty-two studies were fully evaluated (15 qualitative, 62 quantitative and 5 mixed method). Five papers were rated ‘highly rigorous’, 22 ‘rigorous’, 46 ‘less rigorous’, and 9 ‘poor’. Papers rated ‘poor’ were included in synthesis where they addressed issues not covered in more rigorous studies, but their limitations were noted. Distribution of papers across the model and innovations aimed to improve access are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Distribution and quality evaluation of papers across areas of the Access model.

| Area | Highly Rigorous |

Rigorous | Less Rigorous |

Poor | Total * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wider determinants of health | |||||

| Health promotion | - | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| Identification of need | |||||

| People with learning disabilities | - | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Parents / carers | 1 | 7 | 13 | 2 | 23 |

| Others | - | - | - | 1 | 1 |

| Organisational determinants | |||||

| GP services | - | 4 | 5 | - | 9 |

| Dental services | 1 | - | 4 | - | 5 |

| Optometry services | - | - | - | - | 0 |

| Screening / surveillance | 1 | 1 | 6 | - | 8 |

| A&E | - | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| Specialist outpatient clinics | - | 1 | 8 | 1 | 10 |

| Acute services | - | - | 2 | - | 2 |

| Therapy | - | - | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| Entry access | |||||

| GP services | 2 | 7 | 9 | - | 18 |

| Dental services | - | - | - | - | 0 |

| Optometry services | - | - | - | - | 0 |

| Community health services / A&E |

2 | - | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Continuing access | |||||

| Specialist outpatient clinics | - | 3 | 5 | 1 | 9 |

| Inpatient services | - | - | - | - | 0 |

| Therapy | - | - | - | - | 0 |

| Innovation | |||||

| Communication aid | - | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| GP practice | - | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| GP practice based health check | - | 4 | 8 | - | 12 |

| Walk in clinic | - | - | - | 2 | 2 |

Totals exceed number of papers as some address more than one area of the model

We identified a considerable amount of literature on improving the health status of people with learning disabilities, of which ‘access to healthcare’ is a fundamental component. However, much of the literature that initially appeared highly relevant to the review was often only marginally or implicitly related to access, focussing instead on practice issues or guidelines to care. Table 2 indicates the lack of high quality research in this field. Most evidence focused on identifying unmet health need and GP services, evidence in other areas was scant.

Findings

Although this review aimed to identify theory on, as well as barriers to access to healthcare for people with learning disabilities, we found no studies that addressed the theoretical underpinnings to ‘access’. Findings are presented under headings used in the model (figure 1) that guided the review. Evidence reviewed arises from research conducted in the U.K. unless otherwise cited.

Identification of health need

A substantial volume of literature on unmet health needs was reviewed less than a third of which was rigorous or highly rigorous. Several studies (including both more and less rigorous research) demonstrated that between 72% and 94% people with learning disabilities had one or more unmet health need e.g. 13 14. High levels of unmet need signals that people with learning disabilities and carers have difficulty identifying health needs.

Two studies on identification of need by people with learning disabilities themselves suggested that they may have poor bodily awareness 15 and depressed pain responses16. Either of these factors can affect timely responses to physical symptoms. In addition, limited communication skills may reduce capacity to convey identified health needs effectively to a carer.

Carers therefore play a central role in the identification of health need for many people with learning disabilities. However they may have difficulty recognising expressions of need, particularly if the person concerned does not communicate verbally17. Long term relationships between a carer and person with learning disability can assist identification of need because such continuity allows the carer to recognise changes from ‘normal’ health status18. However, despite long-term relationships, carers may still fail to recognise changes in health, particularly those that occur gradually such as deterioration in sight and hearing14.

Seeking access to healthcare is only one amongst a number of possible responses to health need a carer may adopt 19 20. Carers may be reluctant to seek help for what they consider ‘trivial’ complaints2, or where they consider the person would not benefit from intervention, for example in relation to sight testing for a person who does not read nor interact with others3. Carers therefore can also constitute a further barrier.

A limited literature suggested that people with learning disabilities from ethnic minorities do not access services to the same extent as their white counterparts 21 22. Sham 23 suggested that among Chinese families cultural beliefs about the nature of disability and illness may lead to reluctance to accept diagnoses of western medical practitioners, which affects their willingness to seek help.

Organisational barriers to access

A substantial literature was identified covering a wide range of healthcare services, however less than a quarter were rigorous or highly rigorous. Shortage in the provision of mental health services was evident 24, and physical access barriers affecting a range of services were highlighted 25. Signs and notices in health settings were problematic for people with learning disabilities, low literacy levels, or sensory disabilities. Need for adequate provision of communication aids, such as induction loops was identified 25.

Research investigating the organisational barriers experienced by patients and carers from ethnic minorities identified that variability in the availability of interpreters and link workers during consultations created difficulties21 23. Problems were reported due to interpreters lacking competence to translate complex medical information 23.

Evidence suggested that where the organisation of services fails to take account of the needs of parents and their sons or daughters with learning disabilities, willingness to approach services may be affected. For example, parents embarrassed by the behaviour of their son or daughter in waiting areas may be reluctant to seek health advice2.

A small amount of less rigorous literature indicated that lack of interpersonal skills in working with people with learning disabilities amongst mainstream healthcare staff also affects willingness to seek healthcare. People with learning disabilities may perceive that their complaints are not taken seriously25, or that staff are judgemental about their capabilities27. Some parents feel that their concerns about their child's health are not taken seriously when health professionals attribute symptoms to learning disability rather than a medical condition (overshadowing) 28.

Evidence was sought on organisational barriers to accessing population health screening programmes. A small amount of literature was found on cervical screening and mammography. This evidence suggested that not all eligible women with learning disabilities were invited to attend and inappropriate means were often used to inform those who were e.g. 29. Assumptions on the part of general practitioners and carers about the appropriateness of performing these types of cancer screening for more severely disabled women resulted in failure to invite for screening, and non-attendance, respectively30.

Entry (first contact) healthcare

A smaller but significant quantity of evidence was found on entry healthcare almost half of which was rigorous or highly rigorous. This suggested that overall people with learning disabilities may access general practice and dental surgeries less frequently than the general population or other vulnerable groups e.g. 26 31 32. A range of barriers were identified as affecting the GP's ability to provide an effective primary care service, including communication difficulties, time constraints, and examination difficulties 13. Similar difficulties with communication and examination were identified in the only study identified on access to optometry34.

There was substantial agreement amongst GPs that they were responsible for the day to day healthcare of people with learning disabilities e.g. 35 36 37. However Beange et al 13 reported that GPs in their Australian study felt they lacked backup resources to work with people with learning disabilities, and were restricted by a secondary health service not geared to meet the needs of this group.

Audits of preventative healthcare activity using GP records suggested that people with learning disabilities were less likely to receive preventative healthcare 31 35. It was suggested that the considerable challenges faced by GPs in providing healthcare for a presenting condition meant opportunities to undertake preventative work were being missed35.

Continuing healthcare

Evidence on access to continuing and secondary healthcare was extremely small, particularly in view of the wide range of health services potentially involved. Only mental health services were covered in more than one or two studies and these suggested people with learning disabilities had difficulties accessing specialist mental healthcare. Two studies both suggested a lack, or inappropriate provision, of mental health services to children, adults and older adults with learning disabilities 38 39. People with learning disabilities from South Asian communities in the U.K. were shown to have fewer contacts with psychiatrists than those from white communities, despite similar levels of need22, suggesting a double barrier to mental healthcare. Studies on the presence of mental illness in older people with learning disabilities also found significant unmet need, suggesting that carers have difficulty recognising symptoms of mental illness, particularly depression and dementia e.g. 24. However there was evidence that carers were aware of symptoms, but failed to recognise them as indicating mental illness24.

An evaluation of access to specialist services following a health check found referrals to mental health services were not as successful as those to physical health services39. They found some carers disagreed that the person should be referred to psychiatry, believing a referral to a Primary Health Care Team more appropriate.

One study reported 78% of support staff found access to specialist mental health services good40. However, in a separate study most participating mainstream psychiatrists, psychologists, senior nurses and managers described local clinical provision for people with learning disabilities and mental health needs as part of specialist learning disability services41. They reported learning disability services as easier to access than specialist mainstream mental health services. The perception of mental health care as the responsibility of learning disability services suggests some uncertainty over the respective roles of mental health, as opposed to learning disability health services. Current policy promotes the use of mainstream services by people with learning disabilities, however it appears while the label ‘learning disability’ endows entitlement to specialised services to meet exceptional needs, it creates difficulty in referring across to closely related disciplines. Consequently if specialist learning disability services did not provide ‘mental health care’, access to ‘psychiatric’ services could be seen as problematic.

This review aimed to reflect the multi-faceted nature of access to healthcare services but was constrained by the available evidence. The literature on ‘continuing access’ to healthcare was the most ‘compartmentalised’, that is tended to focus on specific issues such as ‘ethnic minorities’, or ‘mental healthcare’. This lead to disjointedness reflecting the narrow focus of studies, but also the low volume of studies identified. However we have endeavoured to integrate these into the overall model.

Innovations aimed at improving access to healthcare

Sixteen studies describing or evaluating interventions aiming to improve access to healthcare were reviewed, less than a third of which were rigorous. Only one study tackled communication barriers. This pilot study evaluated a communication aid and training package for people with learning disabilities aiming to improve their knowledge of their bodies and how to use general practice42. Knowledge improved, but skills were poorly retained in the longer term because most participants had no occasion to use them.

Another initiative aimed to support GPs with a ‘prompt card’ kept with patient's records 43. The card listed support services available and evidence based health issues important in providing healthcare to people with learning disabilities. However after the trial period there were no differences between experimental and control groups in preventative healthcare or referrals.

Most evidence on interventions designed to improve access described health check programmes e.g. 39 44 45. These primary care based checks involved GPs, practice nurses, and/or Community Nurses in Learning Disability. High levels of unmet need were uncovered, suggesting that health checks are effective in overcoming barriers raised by difficulties in identifying or communicating health need by people with learning disabilities, or their carers. Only two studies evaluated the success of such initiatives in improving access to services. One reported that carers felt the health of the person they cared for had improved, but not all referrals to services recommended were acted upon45. Another study, mentioned above, found referrals to psychiatric services did not facilitate access to the service, at least in the twelve months following the check39.

Research therefore demonstrated the effectiveness of health checks in identifying health needs and providing opportunities for preventative interventions, but has yet to establish their effectiveness in achieving improved access to mainstream healthcare services. However it suggests that where a carer determines access, they must be convinced the intervention is necessary otherwise referrals may not be followed through. This is understandable given the logistical difficulties in arranging transport to health services and potential problems faced using them. Staff shortages amongst paid carers, or behavioural challenges on the part of the person with learning disability, must also provide strong disincentives to pursue ‘unnecessary’ health consultations. In addition, organisational barriers to access manifest in shortages of provision, such as those suggested in mental healthcare services, may result in low priority being accorded to those referred through screening.

Finally, two studies described day care centre based ‘walk-in clinics’ for people with learning disabilities. These studies were methodologically ‘poor’ but the only ones identified describing this type of innovation. One clinic focussed specifically on mental health needs and accepted referrals from family or paid carers46 who reported that the clinic made it easier to secure access to mental health services. The second was a general health clinic run by a nurse47. It was reported to be well used and able to identify and remedy need, resulting in time savings for GPs. It was not possible to determine from the reports how effective these services were in improving access to healthcare. However, recent policy7 recommends that people with learning disabilities use mainstream services with appropriate support. This suggests that such segregated services are unlikely to be promoted.

Gaps in research

Reviews of this sort share a basic difficulty in identifying all the available literature. Our consultation and mail shot strategies overcame some barriers to identifying literature however the fact that we were unable to identify literature covering all aspects of our model does not necessarily mean that it does not exist, but omissions should be minimised. Nevertheless, consultations with people with learning disabilities, family and paid carers and national organisations of and for people with learning disabilities, as well as the shortage of evidence in areas of the ‘access’ model, suggested a number of gaps in research. These related to barriers and facilitators to access to healthcare for people with learning disabilities, both before and after a formal demand for health services is made.

Factors operating outside health services

Carers are central to identification of need and support in accessing healthcare, as noted above. They are intimately involved in communication and negotiation with health professionals on issues regarding the health of the person they care for and consequently have a profound influence on the provision of healthcare for these patients. Research is currently lacking on the role of, and support needed by, carers in facilitating access to healthcare for this group.

We found no evidence on access to healthcare for people living in segregated settings such as village style campuses or medium secure units. Our consultations suggested specific issues need investigation such as the use of on-site, as opposed to community, health provision and co-ordination between these two sectors.

Only a limited amount of evidence was found on access to healthcare services for people from ethnic minorities. Thirty four references were identified on use of services by people with learning disabilities from ethnic minorities, but 24 of these did not address access to healthcare. Of the remainder, 3 were unobtainable and a further 4 identified too late to include in the synthesis. Therefore only three publications that specifically addressed access were included in the review 21 22 23. Two of these publications addressed access to services in general, of which health services were a comparatively small part, and one focussed solely on psychiatric services. Some studies (not included) considered the access needs of people from ethnic minorities with a range of disabilities. However the findings were combined so the experience of those with learning disabilities could not be ascertained. Consequently, research concentrating specifically on access to healthcare for this group was lacking, despite the suggested higher prevalence of learning disability among some ethnic minority populations such as the South Asian community49.

Consultation also highlighted the role of professionals in facilitating access to health services. In particular it was reported that a common route to healthcare services for children with severe learning disabilities is through the school nurse based at their special school. However we found no research on the role of school nurses in accessing health services, nor did we find any evidence on the role of other care workers in access to healthcare.

This review sought evidence on access to healthcare across the life span, but little was found on access to healthcare for children and only two studies related to older people with learning disabilities. People with learning disabilities are now surviving into old age48 and therefore there is a growing need for research into access to healthcare services for older people.

Factors within health settings

Evidence on access to health services other than general practice was very limited. We found no evidence on the experiences of, and barriers faced by people with learning disabilities in accessing audiologists and only one study on opticians. This is a considerable omission given the wealth of data on unmet health needs details high levels of sight and hearing problems amongst people with learning disabilities. There was almost no information on access to accident and emergency departments, nor to the wide range of continuing and specialist healthcare services apart from mental health, and this was inadequate.

A theme throughout both the research evidence and consultation was the effect that lack of interpersonal expertise, among the mainstream healthcare workforce in caring for people with learning disabilities, had on willingness to access healthcare. Infrequent contact and reliance on carers for practical support appear to have generated perceptions by some people with learning disabilities that their health complaints are not taken seriously, and by carers that people with learning disabilities are treated as ‘second class citizens’. We found no research on the effect of health professionals' knowledge of, or attitudes towards, people with learning disabilities on their access to healthcare, or how to support staff to promote positive attitudes and practices in working with these patients.

General practice is most frequently accessed by people with learning disabilities and the gateway to the whole range of healthcare services. It is therefore crucial that they gain access to effective consultations and through them appropriate, timely referrals. The literature identified a number of barriers to effective GP care including communication and examination difficulties and time constraints. However apart from the ‘prompt card’ referred to above, we found no research on initiatives aimed at acceptable ways of overcoming these barriers.

Consultation with learning disability health services revealed that they do a great deal of work helping people with learning disabilities to access mainstream health services. However we found no research on the role of specialist learning disability services in facilitating access, or on ways they may support their mainstream colleagues in providing healthcare to this group. Specialist learning disability healthcare professionals potentially have an important role in enabling the mainstream health workforce to become experienced and confident in providing care to patients with learning disabilities.

Conclusion

Identification of evidence on access to healthcare services for people with learning disabilities is vital as part of an ongoing process of appropriate and effective service development. Despite the gaps in evidence noted above, the review highlighted significant barriers to, an initiatives aimed at improving, access to healthcare services for people with learning disabilities. It is important that effort focuses on identifying and implementing innovations effective in overcoming these barriers.

Barriers related to identification of need and communication difficulties run throughout the model of access adopted for this study. People with learning disabilities and their carers require support in identifying need and arranging timely health consultations. Evidence shows that health check programmes are successful in identifying health problems among people with learning disabilities, but there is a lack of evidence on whether, and under what conditions, health checks can be effective as part of routine, mainstream health services. It is vital that success in identifying need is complemented by evidence that patients with learning disabilities subsequently obtain and use appropriate health services.

The review confirmed well-established difficulties in accessing healthcare due to communication problems between people with learning disabilities and health professionals; difficulties examining some of these patients; and time constraints imposed by rigid appointments systems. However research into ways of overcoming these barriers was absent. Effective provision needs patient unhurried consultation as a minimum condition for success. Reconciling this necessity with the demands of busy time-pressured health services needs detailed investigation, and is essential if mainstream health services are to be accessible to those with exceptional needs as well as the general population.

NHS policies 5 6 aim to provide equitable health services to the whole population of England implying that initiatives, such as the National Service Frameworks (e.g. for cancer or mental health), should routinely include people with learning disabilities. Policy for people with learning disabilities 7 recognises that for them to make full use of mainstream health services some support or accommodation will be necessary. ‘Having’ and ‘gaining’ access not only require that the full range of health services is available to people with exceptional needs, but that they are responsive to them. Changes in mainstream healthcare provision, such as adoption of person-centred practices, can address the needs of this group. However, this will only be achieved if the mainstream workforce is experienced and confident in caring for these patients.

Recent governmental initiatives outlined in the NHS Plan6 aim to improve patient involvement within health services. However it is not clear how developing initiatives such as the Expert Patient Programme, Patient and Public Involvement Forums, and Choice and Responsiveness consultations aim to include people with learning disabilities and their advocates as participants. These patients are amongst the most challenging to design services for and deliver services to. Their participation in initiatives of this type can prompt service improvements that will benefit people with a wide range of disabilities. Inclusion requires proactive and supportive approaches to ensure the views and experiences of people with learning disabilities are heard and their health needs met.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all those who contributed their views, experiences and work to this review. We were delighted with the interest and enthusiasm expressed by all those we contacted. We would like to acknowledge the substantial contribution of Angela Swallow, National Primary Care R&D Centre, University of Manchester, in liaising with researchers and learning disability health professionals regarding the review and in facilitating discussion groups with carers. Finally thank you to the Document Supply Unit, John Rylands Library, University of Manchester.

This review was completed between June 2002 and May 2003 and funded by the NHS Service Delivery and Organisation (SDO) R&D Programme. A full report of the review is available on the SDO website: http://www.sdo.lshtm.ac.uk/sdo232002.html

Footnotes

The term learning disability is synonymous with intellectual disability, mental retardation and developmental disability.

Contributor Information

Alison Alborz, National Primary Care R&D Centre.

Rosalind McNally, National Primary Care R&D Centre.

Caroline Glendinning, National Primary Care R&D Centre.

References

- 1.Foundation for People with Learning Disabilities . Learning Disabilities: The Fundamental Facts. London: The Mental Health Foundation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howells G. Are the medical needs of mentally handicapped adults being met? Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. 1986;36:449–453. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson D, Haire A. Health screening for people with mental handicap living in the community. British Medical Journal. 1990;301:1379–80. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6765.1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Schrojenstein Lantman-de Valk HMJ, van den Akker M, Maaskant MA, Haveman MJ, Urlings HFJ, Kessels AGH, Crebolder HFJM. Prevalence and incidence of health problems in people with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 1997;41:42–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.1997.tb00675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Health . The New NHS: Modern, Dependable. London: HMSO; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of Health . The NHS Plan. A plan for investment. A plan for reform. London: the Stationery Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Department of Health . Valuing People: A strategy for learning disability for the 21st century. London: the Stationery Office; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gulliford M, Morgan M, Hughes D, Beech R, Figeroa-Munoz J, Gibson B, et al. Access to Health Care: Report of a scoping exercise for the National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation R & D (NCCSDO) London: NCCSDO; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howells G. Down's syndrome and the general practitioner. Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. 1989 Nov;:470–475. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, Hardey M, Powell J. Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qualitative Health Research. 2002;12:1284–1299. doi: 10.1177/1049732302238251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noblit GW, Hare DW. Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies. Newbury Park, California: Sage; 1988. (Qualitative Research Methods. Sage University Paper 11). [Google Scholar]

- 12.University of Salford Health Care Practice Research and Development Unit. Evaluation Tool for Quantitative Research Studies. 2001. [[accessed 3/1/02]]. http//www.fhsc.salford.ac.uk/hcprdu/tools/quantitative.htm.; Evaluation Tool for Qualitative Research Studies. 2001. [[accessed 3/1/02]]. http//www.fhsc.salford.ac.uk/hcprdu/tools/qualitative.htm.

- 13.Beange H, McElduff A, Baker W. Medical disorders of adults with mental retardation: a population study. American Journal of Mental Retardation. 1995;99(6):595–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerr AM, McCulloch D, Oliver K, McLean B, Coleman E, Law T, et al. Medical needs of people with intellectual disability require regular reassessment, and the provision of client- and carer-held reports. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2003;47:134–145. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2003.00453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.March P. How do people with a mild/moderate mental handicap conceptualise physical illness and its cause? The British Journal of Mental Subnormality. 1991;37:80–91. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilbert-McLeod CA, Craig KD, Rocha EM, Mathias MD. Everyday pain responses in children with and without developmental delays. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2000;25:301–308. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/25.5.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Purcell M, Morris I, McConkey R. Staff perceptions of the communicative competence of adult persons with intellectual disabilities. British Journal of Developmental Disabilities. 1999;45:16–25. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donovan J. Learning disability nurses' experiences of being with clients who may be in pain. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2002;38:458–466. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal and Coping. New York: Springer Publishing Co.; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antonovsky A. Unravelling the mystery of health: How people manage stress and stay well. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steele B, Sergison M. Improving the quality of life of ethnic minority children with learning disabilities. Huddersfield: Huddersfield NHS Trust; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGrother CW, Bhaumik S, Thorp CF, Watson JM, Taub NA. Prevalence, morbidity and service need among South Asian and white adults with intellectual disability in Leicestershire, UK. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2002;46:299–309. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2002.00391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sham S. Reaching Chinese children with learning disabilities in greater Manchester. British Journal of Learning Disabilities. 1996;24:104–109. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moss S, Patel P. The prevalence of mental illness in people with intellectual disability over 50 years of age, and the diagnostic-importance of information from carers. Irish Journal of Psychology. 1993;14(1):110–129. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freeney M, Cook R, Hale B, Duckworth S. Working in Partnership to Implement Section 21 of the Disability Discrimination Act 1995 across the National Health Service. NHS Executive; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh P. Prescription for change: a Mencap report on the role of GPs and carers in the provision of primary care for people with learning disabilities. London: Mencap; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maternity Alliance . Maternity Services for Women with Learning Difficulties: A report of a partnership of midwives, community nurses and parents. London: Maternity Alliance; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carter B, McArthur E, Cunliffe M. Dealing with uncertainty: parental assessment of pain in their children with profound special needs. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2002;38:449–457. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davies N, Duff M. Breast cancer screening for older women with intellectual disability living in community group homes. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2001;45:253–257. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2001.00313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nightingale CE. Issues of access to health services for people with learning disabilities: a case study of cervical screening [PhD Thesis] Cambridge: Anglia Polytechnic University; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whitfield M, Langan J, Russell O. Assessing general practitioners' care of adult patients with learning disability: case-control study. Quality in Health Care. 1996;5:31–35. doi: 10.1136/qshc.5.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lyon JW. The oral health of adults with learning disabilities living within the community in north Warwickshire who do not access the community dental service [Thesis, Master of Dental Science] Birmingham: University of Birmingham; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khan KS, Riet G, Glanville J, et al. Undertaking systematic reviews of research on effectiveness: CRD's guidance for those carrying out or commissioning reviews. 2nd ed. York: Centre for Reviews and Dissemination; 2001. (CRD Report Number 4). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Speechley M. Adults with profound and multiple learning disabilities: perceived and real obstacles to accessing vision testing services [dissertation] Manchester: University of Manchester; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lennox NG, Diggens J, Ugoni A. Health care for people with an intellectual disability: General practitioners' attitudes, and provision of care. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability. 2000;25:127–133. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dovey S, Webb OJ. General practitioners' perception of their role in care for people with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2000;44:553–561. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2000.00269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bond L, Kerr M, Dunstan F, Thapar A. Attitudes of general practitioners towards health care for people with intellectual disability and the factors underlying these attitudes. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 1997;41:391–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.1997.tb00726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beecham J, Chadwick O, Fidan D, Bernard S. Children with severe learning disabilities: needs, services and costs. Children and Society. 2002;16:168–181. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roy A, Martin DM, Wells MB. Health gain through screening - Mental health: Developing primary health care services for people with an intellectual disability. J Intellect Develop Dis. 1997;22:227–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.1997.tb00727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kon Y, Bouras N. Psychiatric follow-up and health services utilisation for people with learning disabilities. British Journal of Developmental Disabilities. 1997;43:20–26. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gravestock S, Bouras N. Services for adults with learning disabilities and mental health needs. Psychiatric Bulletin. 1995;19:288–290. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dodd K. “Feeling poorly”: Report of a pilot study aimed to increase the ability of people with learning disabilities to understand and communicate about physical illness. British Journal of Learning Disabilities. 1999;27:10–15. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones R, Kerr M. A randomized control trial of an opportunistic health screening tool in primary care for people with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 1997;41:409–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.1997.tb00728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hunt C, Wakefield S, Hunt G. Community nurse learning disabilities: A case study of the use of an evidence-based screening tool to identify and meet the health needs of people with learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2001;5:9–18. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paxton D, Taylor S. Access to primary health care for adults with a learning disability. Health Bulletin. 1998;56:686–693. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nadarajah J, Gingell K. A community based walk-in clinic for mentally handicapped adults - is there a need? Psychiatric Bulletin. 1991;15:544–545. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Allan E. Learning disability: promoting health equality in the community. Nursing Standard. 1999;13(44):32–37. doi: 10.7748/ns1999.07.13.44.32.c2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carter G, Jancer J. Mortality in the mentally handicapped: a 50 year survey at the Stoke Park group of hospitals (1930-1980) Journal of Mental Deficiency Research. 1983;27:143–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.1983.tb00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Emerson E, Hatton C. Future trends in the ethnic composition of British Society and among British Citizens with learning disabilities. Tizard Learning Disability Review. 1999;14:28–31. [Google Scholar]