Abstract

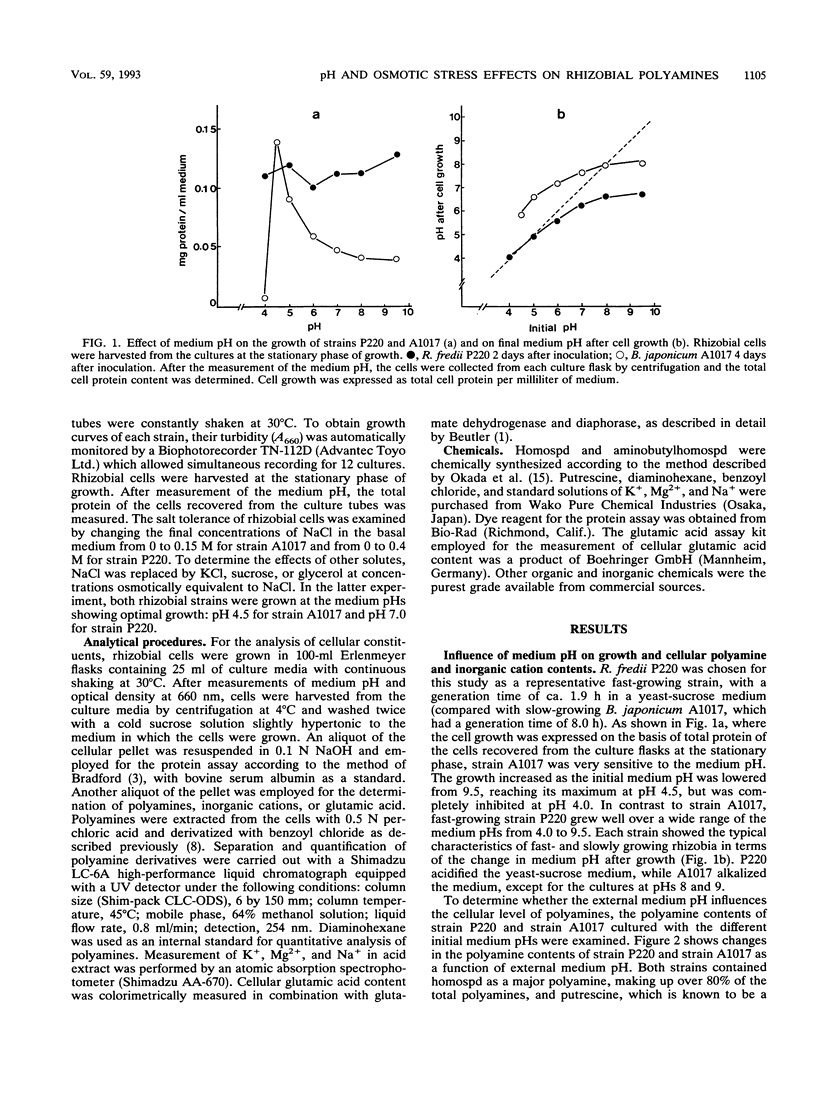

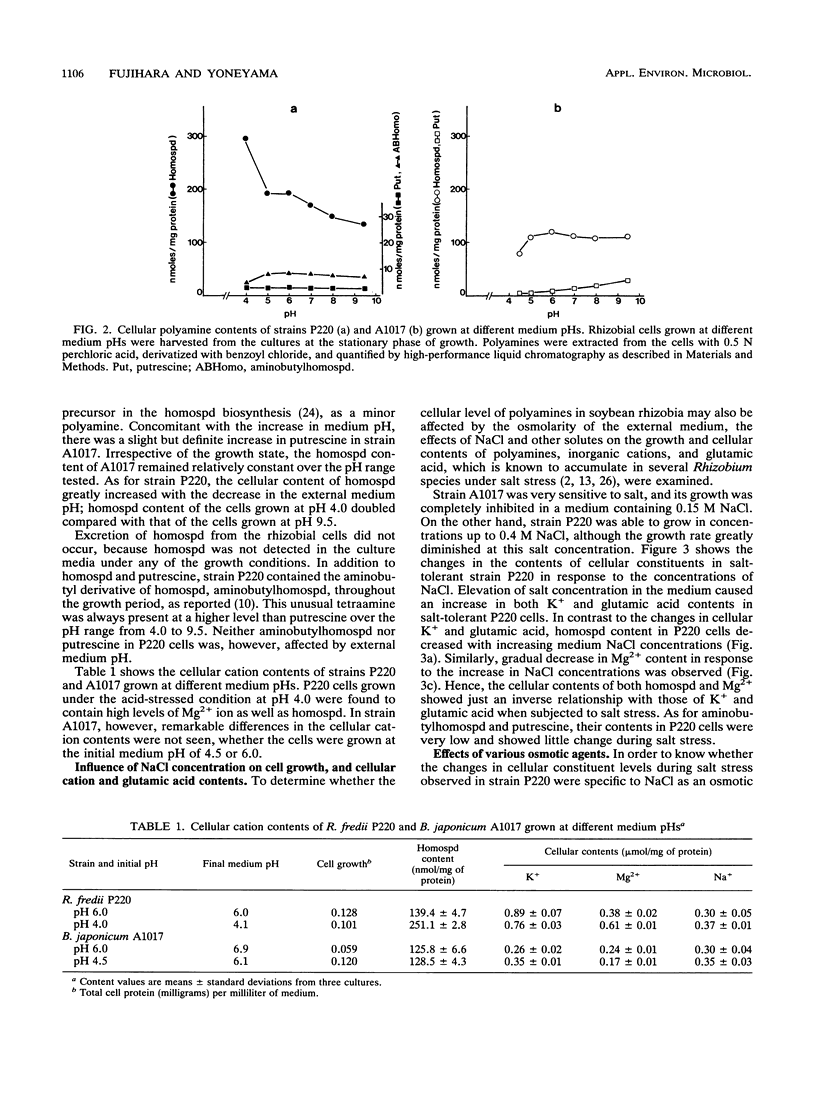

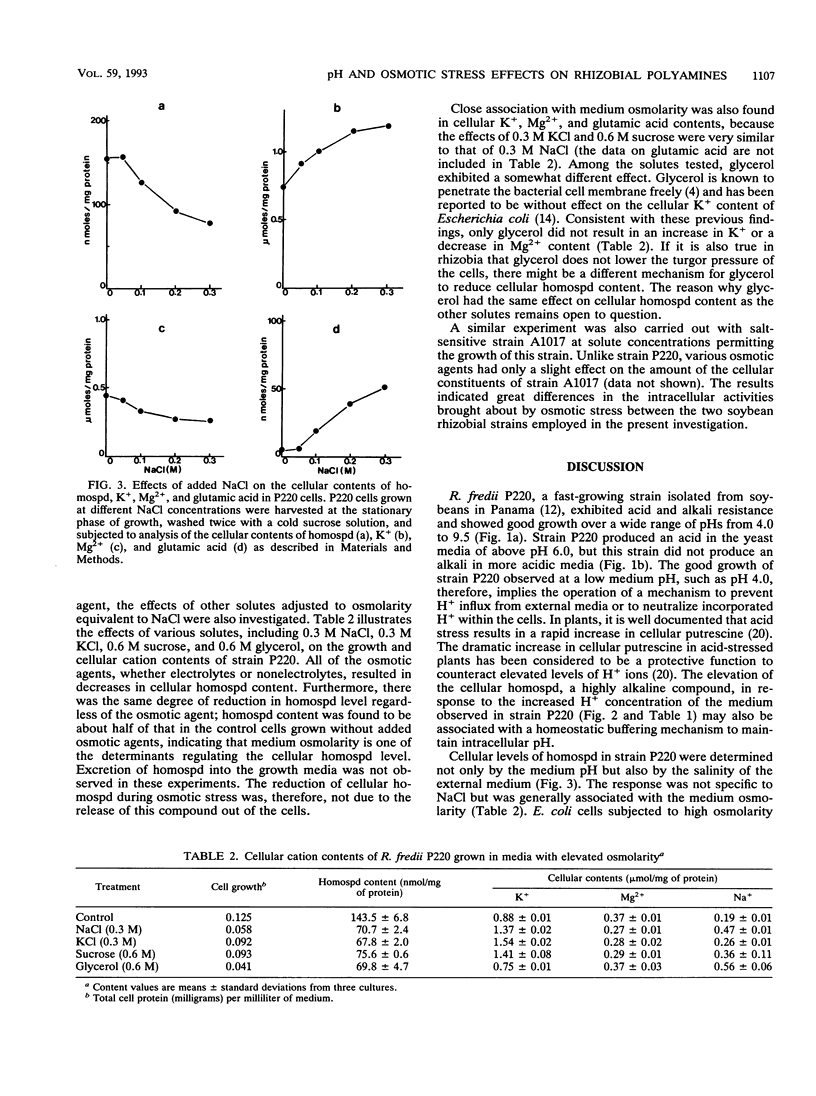

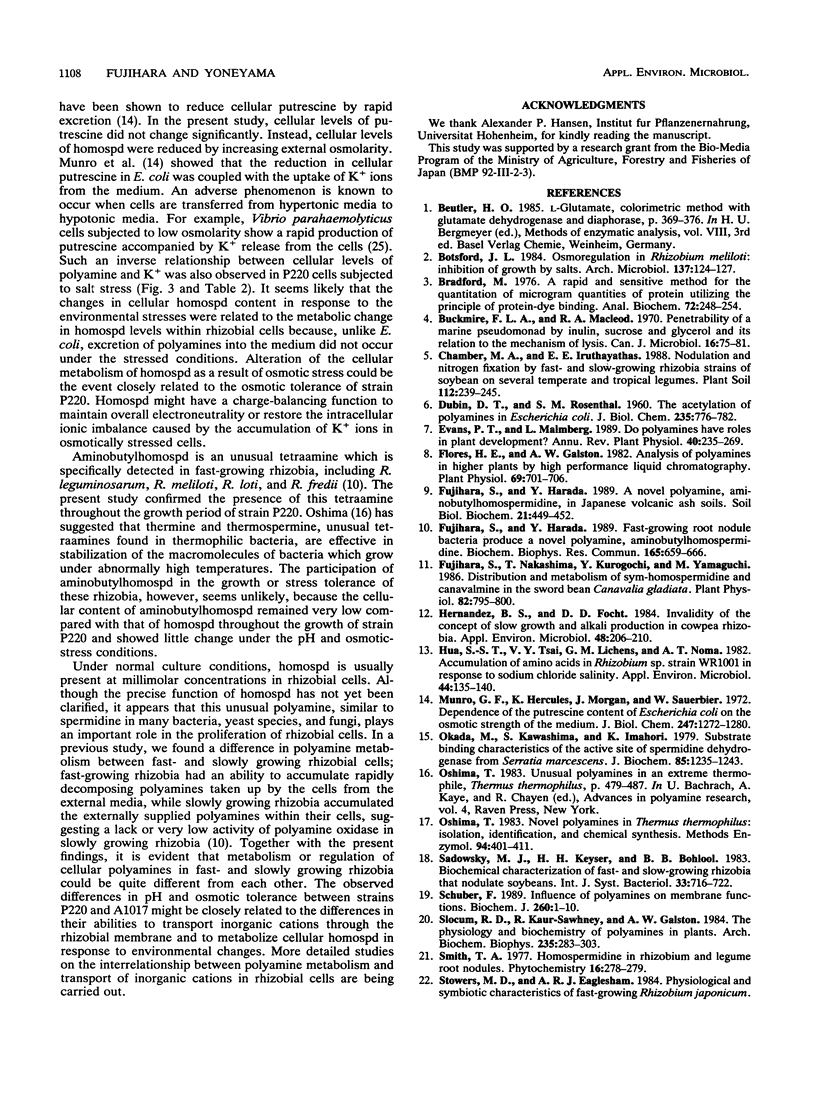

Homospermidine is a polyamine present in its highest concentrations in root nodule bacteria. By using the soybean rhizobia Rhizobium fredii P220 and Bradyrhizobium japonicum A1017, the effects of the pH and osmolarity of the medium on rhizobial growth and cellular polyamine contents were investigated. Elevation of medium pH repressed the growth of slowly growing B. japonicum A1017 and resulted in a slight increase in cellular putrescine, while homospermidine content was not significantly affected. In contrast, in fast-growing R. fredii P220, which showed good growth over a wide range of the medium pHs from 4.0 to 9.5, homospermidine content increased with the lowering of the medium pH. Under the acid-stressed conditions, cellular Mg2+ content in strain P220 also increased. Strain P220 was able to grow in NaCl concentrations up to 0.4 M, while strain A1017 did not grow in media containing 0.15 M NaCl. Glutamic acid and K+ contents of salt-tolerant P220 cells increased in response to NaCl concentrations, but homospermidine and Mg2+ contents were inversely related to the NaCl concentrations. External salinity had no effect on the contents of other polyamines in P220 cells. On the basis of osmotic strength, NaCl, KCl, sucrose, or glycerol induced similar decreases in cellular homospermidine content. These results suggested that the cellular levels of homospermidine in strain P220 may be regulated by mechanisms related to their pH and osmotic tolerance.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bradford M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976 May 7;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckmire F. L., MacLeod R. A. Penetrability of a marine pseudomonad by inulin, sucrose, and glycerol and its relation to the mechanism of lysis. Can J Microbiol. 1970 Feb;16(2):75–81. doi: 10.1139/m70-014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUBIN D. T., ROSENTHAL S. M. The acetylation of polyamines in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1960 Mar;235:776–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores H. E., Galston A. W. Analysis of polyamines in higher plants by high performance liquid chromatography. Plant Physiol. 1982 Mar;69(3):701–706. doi: 10.1104/pp.69.3.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujihara S., Harada Y. Fast-growing root nodule bacteria produce a novel polyamine, aminobutylhomospermidine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989 Dec 15;165(2):659–666. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(89)80016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujihara S., Nakashima T., Kurogochi Y., Yamaguchi M. Distribution and Metabolism of sym-Homospermidine and Canavalmine in the Sword Bean Canavalia gladiata cv Shironata. Plant Physiol. 1986 Nov;82(3):795–800. doi: 10.1104/pp.82.3.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez B. S., Focht D. D. Invalidity of the concept of slow growth and alkali production in cowpea rhizobia. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984 Jul;48(1):206–210. doi: 10.1128/aem.48.1.206-210.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua S. S., Tsai V. Y., Lichens G. M., Noma A. T. Accumulation of Amino Acids in Rhizobium sp. Strain WR1001 in Response to Sodium Chloride Salinity. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982 Jul;44(1):135–140. doi: 10.1128/aem.44.1.135-140.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro G. F., Hercules K., Morgan J., Sauerbier W. Dependence of the putrescine content of Escherichia coli on the osmotic strength of the medium. J Biol Chem. 1972 Feb 25;247(4):1272–1280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada M., Kawashima S., Imahori K. Substrate binding characteristics of the active site of spermidine dehydrogenase from Serratia marcescens. J Biochem. 1979 May;85(5):1235–1243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuber F. Influence of polyamines on membrane functions. Biochem J. 1989 May 15;260(1):1–10. doi: 10.1042/bj2600001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slocum R. D., Kaur-Sawhney R., Galston A. W. The physiology and biochemistry of polyamines in plants. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1984 Dec;235(2):283–303. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(84)90201-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabor C. W., Tabor H. Polyamines in microorganisms. Microbiol Rev. 1985 Mar;49(1):81–99. doi: 10.1128/mr.49.1.81-99.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tait G. H. Bacterial polyamines, structures and biosynthesis. Biochem Soc Trans. 1985 Apr;13(2):316–318. doi: 10.1042/bst0130316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto S., Yamasaki K., Takashina K., Katsu T., Shinoda S. Characterization of putrescine production in nongrowing Vibrio parahaemolyticus cells in response to external osmolality. Microbiol Immunol. 1989;33(1):11–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1989.tb01493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]