Abstract

Proteins of the intermembrane space (IMS) of mitochondria are typically synthesized without presequences. Little is known about their topogenesis. We used Tim13, a member of the ‘small Tim protein’ family, as model protein to investigate the mechanism of translocation into the IMS. Tim13 contains four conserved cysteine residues that bind a zinc ion as cofactor. Import of Tim13 did not depend on the membrane potential or ATP hydrolysis. Upon import into mitochondria Tim13 adopted a stably folded conformation in the IMS. Mutagenesis of the cysteine residues or pretreatment with metal chelators interfered with folding of Tim13 in vitro and impaired its import into mitochondria. Upon depletion of metal ions or modification of cysteine residues, imported Tim13 diffused back out of the IMS. We propose an import pathway in which (1) Tim13 can pass through the TOM complex into and out of the IMS in an unfolded conformation, and (2) cofactor acquisition stabilizes folding on the trans side of the outer membrane and traps Tim13 in the IMS, and drives unidirectional movement of the protein across the outer membrane of mitochondria.

Keywords: folding/intermembrane space/mitochondria/protein translocation/Tim13

Introduction

The vast majority of mitochondrial proteins are encoded in the nucleus. Following synthesis in the cytosol these proteins are imported into the respective mitochondrial subcompartment: the outer membrane, the intermembrane space (IMS), the inner membrane and the matrix. During recent decades many studies have analyzed the translocation of proteins into the mitochondrial matrix resulting in a rather detailed knowledge of this process (for review see Koehler, 2000; Neupert and Brunner, 2002; Pfanner and Geissler, 2001). Matrix proteins are typically made with N-terminal presequences. These serve as targeting signals that are recognized by receptors of the Translocase of the Outer Membrane, the TOM complex. The TOM complex forms a channel which allows transport of the proteins into the IMS. The Translocase of the Inner Membrane, the TIM23 complex, then facilitates protein transport into the matrix in an ATP- and membrane-potential-dependent manner. Thus the electrochemical membrane potential and the chemical potential of ATP hydrolysis are driving unidirectional protein translocation from the cytosol into the matrix. Similarly, inner membrane proteins are imported through the TOM complex and integrated into the inner membrane in a reaction dependent on the membrane potential and, mostly, ATP (for details see Koehler, 2000; Tokatlidis et al., 2000).

Proteins of the IMS fulfill a number of important functions in energy metabolism, transport processes and apoptosis. However, little is known about their biogenesis, in particular by which mechanisms they are translocated from the cytosol across the outer membrane into the IMS. There is not a uniform pathway into the IMS; rather, several radically different pathways exist. Some IMS proteins, like cytochrome b2 and cytochrome b5 reductase, are synthesized with bipartite targeting sequences that consist of a matrix-directing signal followed by a sorting sequence. These proteins employ both TOM and TIM complexes for import (Haucke et al., 1997). Other proteins like adenylate kinase and heme lyases do not use TIM complexes and do not carry presequences (Steiner et al., 1995; Schricker et al., 2002). The proteins belonging to these groups can be of relatively high molecular weight and of complex structure.

However, many, if not most, proteins in the IMS are of small size, typically 7–16 kDa. Examples in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae are Som1 (8.4 kDa), Cox17 (7.9 kDa), Cox19 (11.1 kDa), Tim8 (9.6 kDa), Tim9 (10.2 kDa), Tim10 (10.2 kDa), Tim12 (12.3 kDa), Tim13 (11.2 kDa), Cyc1 (12.2 kDa), Cyc7 (12.7 kDa) and Sod1 (15.7 kDa). As a second common feature, all these small IMS proteins, in their mature form, coordinate cofactors or contain conserved cysteine residues suggesting the binding of cofactors (metal ions or heme) (Louie and Brayer, 1990; Beers et al., 1997; Bauerfeind et al., 1998; Nobrega et al., 2002). The reason for this bias towards small and cofactor-binding proteins is unknown.

How are these small proteins transported into the IMS? The only example of this group of proteins whose import has been studied so far is cytochrome c. Apocytochrome c is translocated by the TOM complex across the outer membrane (Diekert et al., 2001). In the IMS, the heme group is incorporated into apocytochrome c in a reaction catalyzed by cytochrome c heme lyase, a component located on the IMS side of the inner membrane. In the absence of cytochrome c heme lyase, cytochrome c fails to be imported, suggesting that cofactor acquisition is a prerequisite for net translocation across the outer membrane (Nargang et al., 1988; Dumont et al., 1991).

In order to gain insight into the import pathway of IMS proteins, we studied the import of Tim13. Tim13, together with Tim8, forms a soluble hexameric 70 kDa complex in the IMS (Curran et al., 2002) which is involved in the import of a number of inner membrane proteins (Paschen et al., 2000). Tim13 and Tim8 are members of the family of ‘small Tim proteins’ of which Tim9, Tim10 and Tim12 are essential for viability in yeast. Like all members of this protein family, Tim13 contains four cysteine residues in a strictly conserved twin CX3C sequence. This motif has been proposed to coordinate a zinc ion, forming a zinc-finger-like structure (Sirrenberg et al., 1998). Recently it was suggested that, instead of coordinating zinc, the cysteine residues form intramolecular disulfide bonds (Curran et al., 2002). Here we show that import of Tim13 does not require ATP or a membrane potential. Following translocation across the outer membrane, Tim13 adopts a folded conformation. The four conserved thiol groups of Tim13 and the presence of zinc ions are critical both for stable folding and for import of Tim13. Also, for already imported Tim13 protein, zinc binding is required to be retained in the IMS, as depletion of metal ions or modification of cysteine residues causes a release of Tim13 from the IMS. Our observations are consistent with an import pathway in which unfolded small Tim proteins can move through the general import pore of the TOM complex in a bidirectional and random manner. In the IMS the binding of zinc ions to the thiol groups then triggers folding and acquisition of the native state which leads to trapping of the small Tim proteins in the IMS and thereby to net translocation.

Results

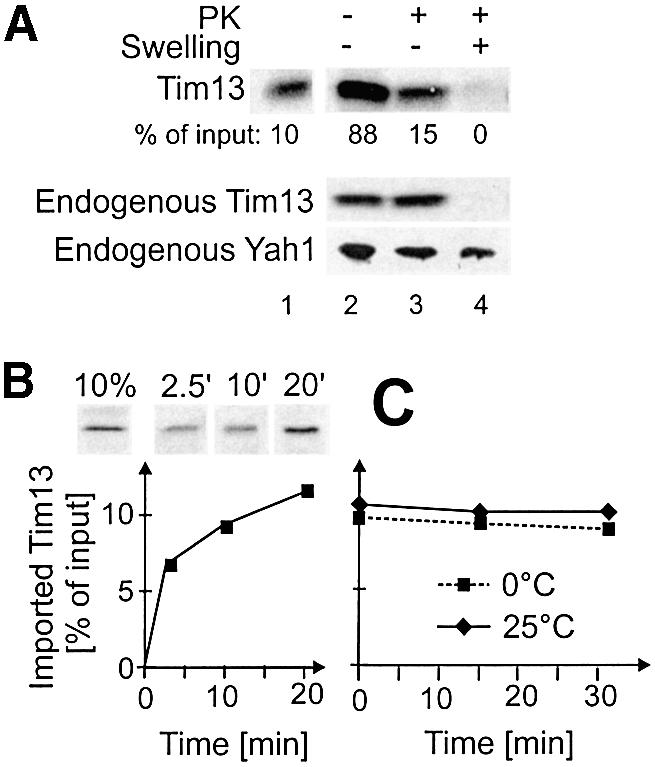

The precursor of Tim13 can be imported into isolated mitochondria

To study the import process of Tim13 into the IMS in an in vitro reaction Tim13 was synthesized in reticulocyte lysate in the presence of [35S]methionine and incubated with isolated yeast mitochondria (Figure 1A). Following incubation, most Tim13 was found in association with mitochondria, indicating an efficient binding of Tim13 precursor protein to the organelle (lane 2). A fraction of Tim13 (15%) was inaccessible to added protease and thus completely translocated across the outer membrane (lane 3). This efficiency of in vitro import of Tim13 is comparable to that of other mitochondrial precursor proteins (cf. Leuenberger et al., 1999). The imported Tim13 protein was completely degraded by protease after opening of the outer membrane by hypotonic swelling (lane 4). Thus translocation of Tim13 into the IMS can be analyzed in an in vitro import reaction.

Fig. 1. Import of Tim13 into the IMS of isolated mitochondria. (A) Radiolabeled Tim13 was incubated for 15 min with isolated mitochondria. Mitochondria were reisolated and either mock treated (lane 2) or incubated with proteinase K (PK) under iso-osmotic (lane 3) or hypo-osmotic (swelling, lane 4) conditions. Mitochondrial proteins were analyzed by SDS–PAGE and autoradiography. Efficiency of import is expressed as percentage of Tim13 present in the import reaction. Lane 1 shows 10% of total Tim13 protein used per lane. For control, endogenous Tim13 and the matrix protein Yah1 were detected by immunoblotting. (B) Tim13 was incubated with mitochondria for the time periods indicated. Mitochondria were reisolated and treated with proteinase K, and the amount of imported Tim13 was determined as in (A). (C) Translocated Tim13 stays in mitochondria. Tim13 was imported for 25 min into mitochondria. Non-imported material was removed by trypsin treatment. Subsequently, trypsin was inactivated by addition of soybean trypsin inhibititor. Mitochondria were reisolated and incubated for the time periods indicated at 0°C (dashed line) or 25°C (solid line). Mitochondria were collected by centrifugation and the amount of Tim13 in the mitochondrial fraction was quantified.

Next we assessed the kinetics of Tim13 import (Figure 1B). About 7% of Tim13 precursor was imported within 2 min of the reaction. Within 20 min the amount of imported Tim13 increased to 12%; longer incubations did not lead to a further increase.

We asked whether Tim13 is transported in a unidirectional manner. Tim13 was incubated with mitochondria. Then surface-bound Tim13 was removed by trypsin treatment. Upon further incubation at 0°C or 25°C release of Tim13 from the IMS was not observed (Figure 1C). Thus import of Tim13 into the IMS of mitochondria was vectorial.

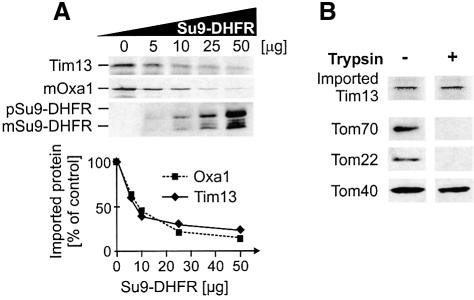

Tim13 shares part of its import route with matrix proteins

Does Tim13 use the general import pathway of mitochondrial preproteins? To address this question, radiolabeled Tim13 was co-imported with increasing amounts of the unlabeled matrix-directed precursor Su9-DHFR, consisting of the N-terminal 69 residues of subunit 9 of the Neurospora crassa ATP synthase fused to mouse dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) (Figure 2A). In the presence of Su9-DHFR import of Tim13 was strongly diminished, as was import of a matrix-targeted precursor protein, Oxa1. This indicates that Tim13 and matrix-localized proteins share a common step in their import pathways. Binding to the same receptors and/or translocation through the general insertion pore of the TOM complex may represent such common reactions.

Fig. 2. Tim13 and matrix-targeted preproteins share a common step in the import pathway. (A) Radiolabeled Tim13 and Oxa1 were synthesized in vitro and mixed with the amounts of recombinant Su9-DHFR precursor indicated. Then 50 µg of mitochondria per reaction were added. Following incubation for 10 min, non-imported material was removed by treatment with proteinase K. The amounts of imported Tim13 and mature Oxa1 (mOxa1) were analyzed by radiography. Su9-DHFR levels were detected by immunoblotting. The amount of imported radioactive material was quantified and related to the amount imported in the absence of Su9-DHFR precursor. (B) Import of Tim13 is independent of surface receptors. Mitochondria were treated with 100 µg/ml trypsin for 20 min on ice. Trypsin was inactivated. Mitochondria were reisolated and incubated with Tim13. After 20 min, non-imported Tim13 was removed by digestion with proteinase K and the amount of imported Tim13 determined by autoradiography (upper lane). The levels of the receptor subunits Tom22 and Tom70, and of the pore-forming component of the TOM complex, Tom40, were analyzed by immunoblotting. mSu9-DHFR and pSu9-DHFR; mature and precursor forms of Su9-DHFR.

To assess a possible requirement of the receptor subunits of the TOM complex, we imported Tim13 into mitochondria in which the receptor domains were removed by pretreatment with trypsin. Removal of receptors interferes with the import of many preproteins into mitochondria (Pfaller et al., 1989). In contrast, trypsin pretreatment of mitochondria had no effect on the import of Tim13 (Figure 2B). Thus receptor domains appear not to be critical for Tim13 translocation into the IMS. The observed competition with matrix-targeted proteins is likely due to a shared translocation route of both proteins through the general insertion pore in the TOM complex.

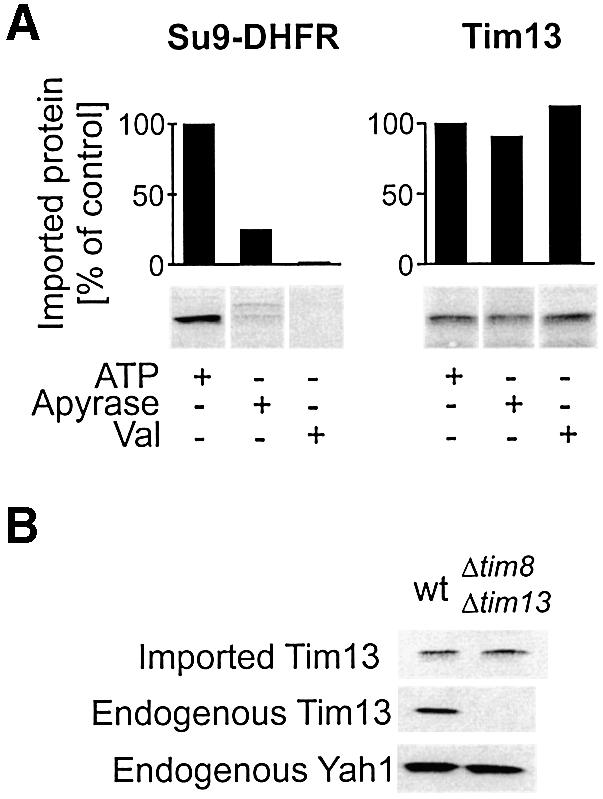

Import of Tim13 does not require ATP, membrane potential or assembly into the Tim8/13 complex

How is translocation of Tim13 from the cytosol into the IMS energetically driven? The import of precursor proteins into the mitochondrial matrix requires both ATP hydrolysis and the membrane potential. Accordingly, import of Su9-DHFR is strongly compromised following depletion of mitochondrial ATP levels by apyrase pretreatment or dissipation of the membrane potential by valinomycin (Figure 3A, left panel). In contrast, the import of Tim13 into the IMS was unaffected under these conditions (Figure 3A, right panel).

Fig. 3. Import of Tim13 is independent of ATP, the membrane potential and assembly into the Tim8/13 complex. (A) Wild-type mitochondria (50 µg) were preincubated for 10 min at 25°C in the presence of 2 mM ATP, or 25 mU/µl apyrase to deplete mitochondrial ATP levels or 5 µM valinomycin (Val) to dissipate the membrane potential. Then radiolabeled Su9-DHFR precursor or Tim13 protein was added and further incubated for 10 min. Non-imported material was removed by protease treatment and the levels of imported proteins quantified following SDS–PAGE and autoradiography. (B) Import of Tim13 into Δtim8/Δtim13 mitochondria. Mitochondria of a wild-type and a Δtim8/Δtim13 double-mutant strain were incubated with radiolabeled Tim13 protein for 10 min. Import efficiency was assessed as in (A). Endogenous Tim13 and Yah1 levels in the mitochondria were determined by immunoblotting.

Another potential driving force for vectorial translocation could be provided by the assembly reaction of Tim13 on the trans side of the membrane. The endogenous Tim13 is part of a soluble complex in the IMS, consisting of three Tim13 and three Tim8 subunits (Curran et al., 2002). We tested whether the presence of unassembled Tim8 or the Tim8/13 complex in the IMS is a prerequisite for Tim13 translocation across the outer membrane. Mitochondria were isolated from a yeast strain in which the genes for both TIM8 and TIM13 were deleted (Paschen et al., 2000). Radiolabeled Tim13 was imported into these Δtim8/Δtim13 mitochondria with the same efficiency as into wild-type mitochondria (Figure 3B). Thus assembly into the complex cannot be responsible for unidirectionality of Tim13 import. In summary, the vectorial translocation of Tim13 into the lumen of the IMS appears not to depend on ATP, the membrane potential or assembly into the Tim8/13 complex.

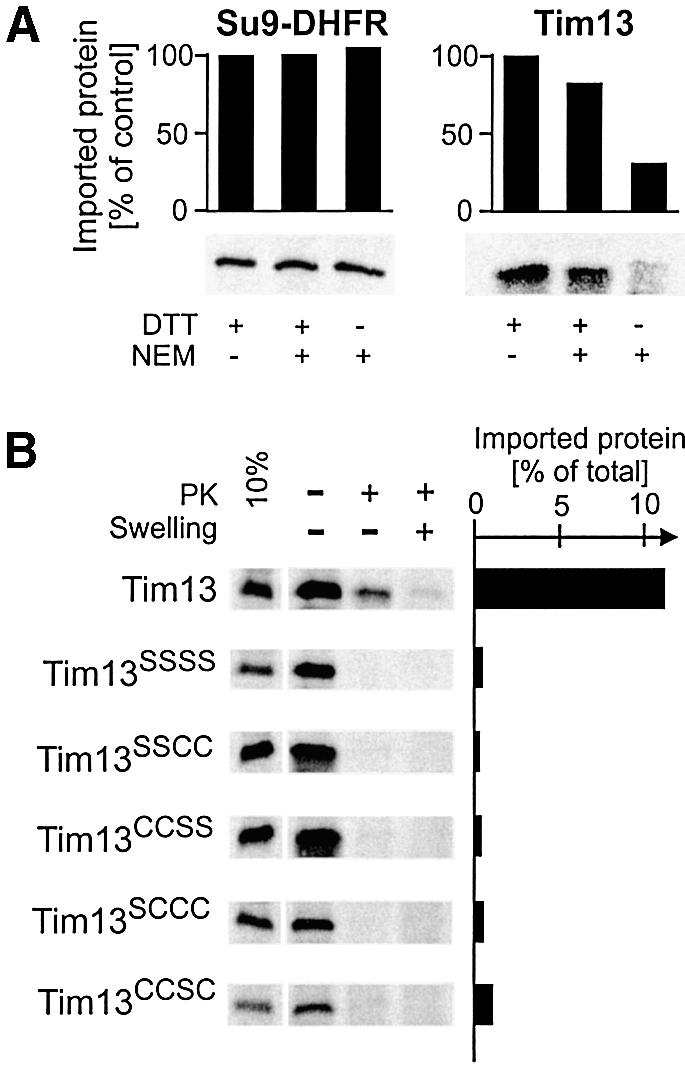

Free thiol groups on Tim13 are essential for translocation into the IMS

Folding of a polypeptide following translocation could be a mechanism to trap it on the trans site of the membrane (Simon et al., 1992). Folding of Tim13 in the IMS might be triggered by acquisition of the cofactor zinc or by formation of disulfide bridges in the conserved twin CX3C motif of Tim13. Both modifications were observed in purified proteins of the small Tim family (Sirrenberg et al., 1998; Curran et al., 2002). Since both incorporation of zinc and formation of disulfide bridges apparently require the presence of free thiol groups, we tested whether modifications of the cysteine residues affects Tim13 import. Radiolabeled Tim13 was treated with N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) to derivatize free thiol groups. After inactivation of free NEM the modified precursor was incubated with mitochondria and the amount of imported protein was quantified (Figure 4A). The import of Tim13 was strongly inhibited upon NEM treatment, in contrast with import of Su9-DHFR which was analyzed as a control. Thus free thiol residues are critical for import of Tim13 into the IMS.

Fig. 4. Free thiol groups are essential for import of Tim13. (A) Radiolabeled Su9-DHFR precursor and Tim13 protein were preincubated for 30 min on ice in the presence of NEM and/or DTT as indicated. Then DTT levels in all samples were adjusted to 20 mM to quench unreacted NEM and mitochondria were added. Following incubation for 10 min, mitochondria were treated with protease. Imported proteins were quantified and import efficiencies expressed in relation to the reactions lacking NEM. (B) Radiolabeled wild-type or cysteine-to-serine mutants of Tim13 were incubated with mitochondria for 20 min. The samples were split into three aliquots and either mock treated or incubated with proteinase K under iso-osmotic or swelling conditions. Protein import into the IMS resulted in a protein species which is inaccessible to protease under non-swelling conditions. The leftmost lane shows 10% of the Tim13 input (left panel). The import efficiencies were quantified and expressed in relation to total Tim13 protein used (right panel).

To study the requirement for thiol groups in the twin CX3C motif further, we constructed Tim13 mutants in which the four conserved cysteine residues were replaced by serine residues. The Tim13SSSS variant was not imported, confirming a crucial role of thiol groups in Tim13 translocation (Figure 4B). Is the presence of only one of the two CX3C motifs sufficient to allow Tim13 import? We constructed mutants in which the thiol groups of one motif were altered to hydroxyl groups. Neither the resulting Tim13SSCC nor Tim13CCSS mutants could be imported into isolated mitochondria. Even replacement of single cysteine residues in the twin CX3C motif completely abolished import of Tim13 (Figure 4B, Tim13SCCC and Tim13CCSC). Thus, the presence of the four thiol residues of the twin CX3C signature is a prerequisite for translocation of Tim13. This indicates an essential role of this conserved motif in the topogenesis of small Tim proteins.

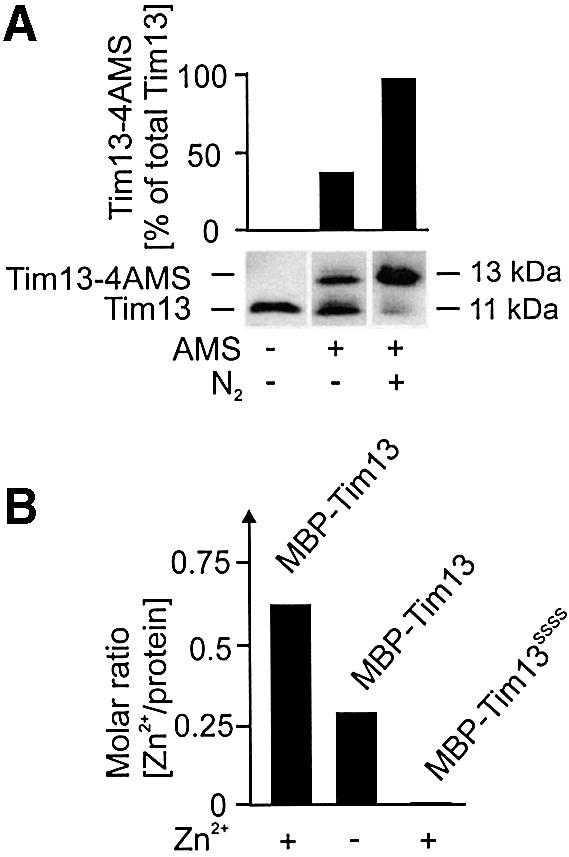

The twin CX3C motif of endogenous Tim13 contains reduced thiol groups

Recently it was shown that small Tim proteins contained disulfide bonds when they were purified from isolated mitochondria (Curran et al., 2002). To assess the redox state of the thiol groups in Tim13 as it is present in the cell, we employed a chemical modification technique. The chemical reagent 4-acetamido-4′-maleimidylstilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (AMS) specifically and efficiently reacts with reduced thiol groups. This modification decreases the electrophoretic mobility of the modified proteins (Kobayashi and Ito, 1999). To avoid any potential oxidation of thiol groups by oxygen during the experiment, we prevented exposure of the endogenous Tim13 protein to oxygen. Instead of isolating mitochondria by subcellular fractionation, we converted yeast cells to spheroplasts by removing the cell wall using a modified protocol that did not employ reducing agents like dithiothreitol (DTT). During this process the plasma membrane remained intact. The spheroplasts were opened by sonication in deoxygenated buffer in the presence of AMS. Following incubation for 2 h under nitrogen, the electrophoretic mobility of Tim13 was determined (Figure 5A). Modification of virtually all of the endogenous Tim13 protein was observed. In contrast, when the cellular extract was prepared in air a significant fraction of the endogenous Tim13 could not be modified by AMS. Apparently, oxidation of the cysteine residues in the protein occurs by oxygen after lysis of the cells. Likewise, only half of the Tim13 protein isolated from mitochondrial extracts could be modified by AMS (not shown). We conclude that in vivo the cysteine residues in the twin CX3C motif of Tim13 are present in the reduced state and are not oxidized to form disulfide bridges.

Fig. 5. Endogenous Tim13 contains free thiol groups. (A) Cell walls were removed from wild-type yeast cells under non-reducing conditions in iso-osmotic buffer. The resulting spheroplasts were reisolated and resuspended in either AMS-free buffer or AMS-containing buffer with or without oxygen depletion. The spheroplasts were opened by sonication under a nitrogen atmosphere and the AMS was allowed to react with free thiol groups for 2 h. Then, proteins were precipitated by addition of TCA and resolved by SDS–PAGE. Tim13 was detected by immunoblotting and the ratio of modified to total Tim13 was determined. Addition of one AMS molecule leads to a size shift of 540 Da (Kobayashi and Ito, 1999), and thus about 2 kDa for the four cysteine residues present in Tim13. (B) Zinc content of purified Tim13 fusion proteins. Wild-type and cysteine-to-serine mutant forms of Tim13 fused to MBP were purified from E.coli. Bacteria were lysed in a buffer containing or lacking 200 µM zinc acetate as indicated. Fusion proteins were bound to an amylose resin and extensively washed with buffer lacking zinc ions. Following release of the fusion proteins from the resin, the content of zinc in the samples was analyzed by ICP-AE spectroscopy. Mean values of two independent experiments are shown. The figure depicts the molar ratio of zinc to protein in the samples.

The ability to bind zinc ions was reported for several members of the small Tim family (Sirrenberg et al., 1998; Hofmann et al., 2002). To test whether Tim13 also binds zinc ions and whether this property depends on the cysteine residues in the protein, we expressed Tim13 and Tim13SSSS as fusion proteins in Escherichia coli. These proteins were isolated in either a zinc-free lysis buffer or a buffer containing 200 µM zinc ions. DTT was omitted due to its ability to chelate metal ions. Following protein purification and extensive washing with zinc-free buffer, the zinc content was determined by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission (ICP-AE) spectroscopy (Figure 5B). In the samples that were lysed in the presence of zinc, zinc ions were co-purified with wild-type Tim13 in almost equimolar concentrations. If cells were lysed in a zinc-free buffer, a significant fraction of Tim13 still contained zinc, indicating that zinc binding occurred in the cells. Other metal ions, such as iron and cadmium, were not detected. In contrast with wild-type Tim13, the Tim13SSSS mutant protein contained no zinc even upon lysis in zinc-containing buffer. This indicates that Tim13 has the capacity to bind zinc ions, and the cysteine residues in the twin CX3C motif are essential for this property.

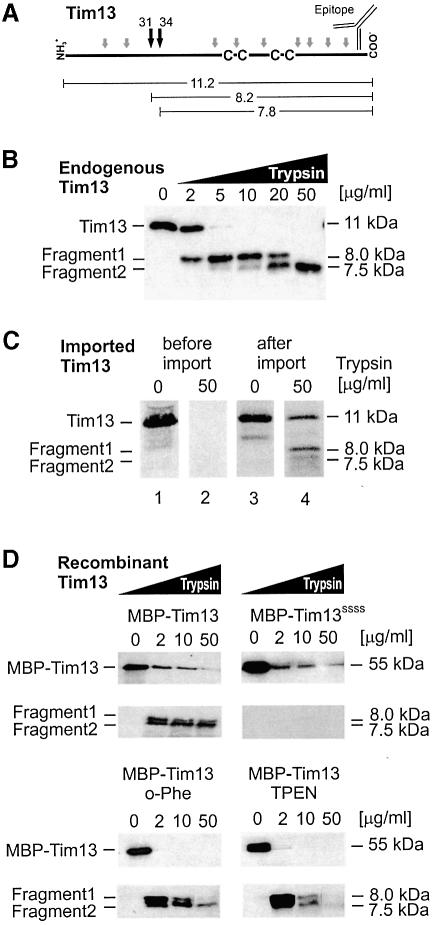

Endogenous Tim13 contains a trypsin-resistant core domain

Trypsin treatment of Tim13 that was released from isolated mitochondria by hypo-osmotic treatment yielded two characteristic protease-resistant fragments (Figure 6B). These fragments were recognized by antibodies raised against the C-terminus of Tim13. The apparent molecular sizes of these fragments are consistent with cleavage at positions Lys31 and Lys34. This indicates that the region containing the twin CX3C motif forms a stably folded domain, as has been reported for other small Tim proteins (Curran et al., 2002; Hofmann et al., 2002).

Fig. 6. Folding of Tim13 generates a C-terminal protease-resistant protein domain. (A) Structure of the Tim13 protein. Potential trypsin cleavage sites are depicted by grey arrows; black arrows indicate lysine residues 31 and 34 which presumably lead to the generation of the protease fragments detected with folded Tim13. The calculated molecular masses (kDa) of respective fragments and the position of the binding site of the Tim13-specific antibody are depicted. (B) Endogenous Tim13 contains a protease-resistant domain. Mitochondria (50 µg) were swollen to release proteins from the IMS. Membrane proteins were removed by centrifugation. Aliquots of the supernatants were incubated with trypsin at the concentrations indicated for 20 min on ice. Trypsin digestion was stopped by addition of TCA. Immunoblotting revealed two specific fragments with apparent molecular masses of 7.5 and 8 kDa. (C) Tim13 acquires a partially protease-resistant conformation upon import. Radiolabeled Tim13 was either directly incubated in the absence (lane 1) or presence (lane 2) of 50 µg/ml trypsin, or first imported into mitochondria for 10 min. Lane 3, Tim13 protein associated with the mitochondria. Following import the mitochondria were opened by hypotonic swelling and treated with trypsin as in lane 2. The protein was precipitated by TCA and applied to SDS–PAGE (lane 4). The residual amount of full-length Tim13 was most likely due to incomplete swelling of the mitochondria. (D) Folding of recombinant Tim13 depends on the ability to bind zinc. Upper panel: wild-type Tim13 and the cysteine-to-serine mutant were isolated as fusion proteins with MBP and incubated with increasing amounts of trypsin as indicated. Lower panel: the Tim13 fusion protein was treated for 15 min with 10 mM EDTA and either 2 mM o-phenanthroline (o-phe) or 0.5 mM TPEN to chelate zinc ions and then incubated with trypsin. The formation of the protease-resistant fragments was analyzed by immunoblotting with Tim13-specific antibodies.

Trypsin digestion of Tim13 synthesized in vitro did not generate any protease-resistant forms, indicating an unfolded structure of this species (Figure 6C, lanes 1 and 2). In contrast, when Tim13 was first imported into mitochondria and then released from the IMS by hypotonic swelling, it could be cleaved by added trypsin to yield the fragments characteristic of folded Tim13 (Figure 6C, lanes 3 and 4). From this we conclude that Tim13 adopts a folded conformation following translocation into the IMS.

Are the cysteine residues in Tim13 critical for stable folding? We expressed both wild-type Tim13 and the Tim13SSSS mutant as fusions with maltose binding protein (MBP) in E.coli. The fusion proteins were purified and incubated with increasing amounts of trypsin. Whereas wild-type Tim13 was converted into the protease-resistant fragments, Tim13SSSS was completely degraded (Figure 6D). This shows that the cysteine residues are essential for stable folding of Tim13. To investigate a possible role of zinc ions for the stability of Tim13, the recombinant Tim13 fusion protein was incubated with chelators to remove metal ions. Incubation with o-phenanthroline or N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis(2-pyridylmethyl)-ethylenediamine (TPEN), a chelator specific for transition metals, significantly destabilized Tim13 (Figure 6D, lower panel). From this we conclude that upon ligation of zinc ions by the cysteine residues in Tim13 the protein adopts a tightly folded conformation and therefore acquires resistance to digestion by trypsin.

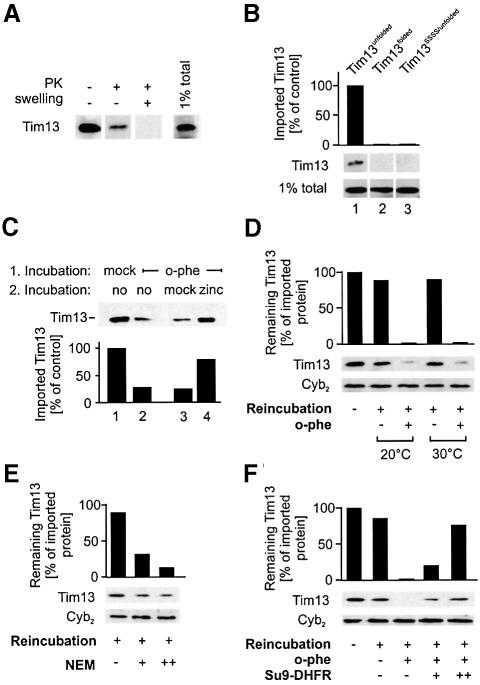

Binding of zinc ions is required for translocation of Tim13 across the outer membrane

Mutation of the conserved cysteine residues in Tim13 affected both its stable folding and its import into mitochondria. To analyze the role of cofactor-dependent folding on the import of Tim13, we set up an import assay using chemical amounts of Tim13. Recombinant Tim13 was obtained by expression in E.coli and purified. The protein was unfolded by treatment with guanidinium hydrochloride and maintained in a reduced state by addition of β-mercaptoethanol. Following incubation with 100 µg of Δtim8/Δtim13 mitochondria, about 20 ng of this protein was imported into the IMS and could be detected by immunoblotting (Figure 7A).

Fig. 7. Import of chemical amounts of Tim13 is dependent on metal ions. (A) Mitochondria (50 µg) were isolated from Δtim8/Δtim13 cells and incubated with 1 µg unfolded Tim13 protein for 20 min at 25°C. Mitochondria were reisolated and exposed to proteinase K (PK) under swelling or non-swelling conditions as indicated. Tim13 protein levels in the samples were detected by immunoblotting. (B) Tim13 and Tim13SSSS were unfolded or mock treated and used for import into Δtim8/Δtim13 mitochondria as described in (A). (C) Δtim8/Δtim13 mitochondria were incubated without (lane 1) or with (lanes 2–4) EDTA and o-phenanthroline. The mitochondria were either directly used for import of unfolded Tim13 (lanes 1 and 2) or after centrifugation through a sucrose cushion. In the sample shown in lane 4, 10 µM zinc acetate was added to the sucrose cushion to re-establish the zinc levels in the mitochondria. After the import reaction, the mitochondria were reisolated and imported Tim13 was detected by immunoblotting. The signals were quantified by densitometry and are expressed in relation to the mock-treated sample. (D) Incubation with chelators led to the release of already imported Tim13. Tim13 was imported as described in (A). Non-imported Tim13 was removed by trypsin treatment on ice (50 µg/ml) and trypsin was inactivated with soybean trypsin inhibitor. Then the mitochondria were 10-fold diluted in 0.6 M sorbitol and 20 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.4 and incubated for 30 min at 0, 20 or 30°C in the absence or presence of 10 mM EDTA and 2 mM o-phenanthroline (o-phe) as indicated. Then material released from the mitochondria was degraded by incubation with proteinase K. Western blot signals for the IMS protein cytochrome b2 are shown to insure intactness of the outer membrane. (E) Tim13 is released from mitochondria upon NEM treatment. Tim13 was imported into mitochondria as described for D, but an import buffer free of β-mercaptoethanol was used. After trypsin treatment the mitochondria were incubated with 0, 1 or 5 mM NEM for 30 min and released Tim13 was degraded by proteinase K. (F) Tim13 was imported into mitochondria as described in (D) with the exception that 1 mM ATP and 1 mM NADH were added to the import reaction. During the reincubation with the chelators, 0, 5 or 20 µg of Su9-DHFR were added to assess competition of Tim13 release and precursor import.

Unfolding of Tim13 was essential for its translocation competence as omission of the denaturing step led to a non-importable form of Tim13 (Figure 7B, lane 2). This again indicates that the protein is transported through the TOM complex in an unfolded conformation. The cysteine-to-serine mutant of Tim13, which is unable to adopt a zinc-stabilized protein fold, was not imported even upon unfolding of the protein (Figure 7B, lane 3).

To assess more directly the significance of cofactor acquisition for the import of Tim13, we tested whether depletion of zinc ions in mitochondria affects the import of Tim13. Mitochondria were preincubated in the absence or presence of EDTA and o-phenanthroline before chemical amounts of Tim13 were added (Figure 7C, lanes 1 and 2). This depletion of metal ions strongly diminished the import of Tim13, showing that metal ions play an important role in this process. To confirm that this effect is caused by lowered zinc levels in the mitochondria, the chelators were removed by centrifugation of the preincubated mitochondria through a zinc-containing sucrose cushion. This almost completely restored the ability of the mitochondria to import Tim13 (Figure 7C, lane 4). In summary, vectorial translocation of Tim13 into the IMS of mitochondria is dependent on an unfolded state of the precursor on the cis side of the membrane and on the presence of zinc ions in the IMS that stabilize folding of Tim13 following its translocation through the TOM complex.

Next we tested whether zinc binding is required for already imported Tim13 protein to stably remain in the IMS. Following import of purified Tim13 into isolated Δtim8/Δtim13 mitochondria, non-imported material was removed by trypsin treatment and the mitochondria were further incubated in the presence or absence of chelators (Figure 7D). Depletion of metal ions led to a strong reduction of Tim13 from the IMS, indicating that metal binding to Tim13 is critical for its retention in the mitochondria. This is further supported by the observation that incubation of mitochondria with the cysteine-modifying agent NEM likewise released imported Tim13 from the IMS (Figure 7E). Thus newly imported Tim13 is only maintained in Δtim8/Δtim13 mitochondria under conditions that stabilize a folded conformation of the protein.

Does the release of Tim13 occur through the TOM complex? To address this question we tested whether the release of imported Tim13 is affected by adding an excess of a matrix-targeted precursor which blocks the TOM complex. As shown in Figure 7F, the presence of Su9-DHFR precursor in chemical amounts strongly decreased the release of Tim13 upon depletion of metal ions. This suggests that depletion zinc ions, and as a consequence unfolding of Tim13 in the IMS, allows its retrograde movement through the TOM complex out of the mitochondria. This again suggests that the apoform of Tim13 can equilibrate between cytosol and the IMS through the TOM channel.

Discussion

The conserved cysteine residues in small Tim proteins bind zinc ions

Two alternative structural arrangements of the cysteine residues of the twin CX3C motif of small Tim proteins have been proposed. For several small Tim proteins the ability to bind zinc ions has been demonstrated and a zinc-finger-like structure of the CX3C motif has been suggested (Sirrenberg et al., 1998; Hofmann et al., 2002). On the other hand, the formation of disulfide bond pairs between the conserved cysteine residues in small Tim proteins has been reported (Curran et al., 2002). Our observations strongly support a function of the CX3C motif in zinc binding for the following reasons: (1) mutation of one cysteine residue is sufficient to abrogate Tim13 import although one stabilizing disulfide bridge should still be able to form; (2) addition of large amounts of reducing reagents like DTT or β-mercaptoethanol did not affect Tim13 import; (3) the cysteine residues in Tim13 were entirely present in a reduced form when the cells were opened under non-oxidizing conditions; (4) Tim13 was rapidly oxidized by aerobic oxygen post-lysis explaining the disulfide bridges in small Tim proteins observed by Curran and co-workers (Curran et al. 2002); (5) removal of metal ions by chelating reagents increased the protease accessibility of recombinant Tim13; (6) zinc ions in mitochondria were essential for efficient import into and persistent localization within mitochondria; (7) treatment with NEM, which reacts with thiol groups but not with disulfide bridges, caused the release of imported Tim13 from the IMS; (8) zinc ions were shown to be required for the function of the small Tim protein complexes (Sirrenberg et al., 1998; Paschen et al., 2000; Lister et al., 2002). In addition, there is complete conservation of the spacing of the cysteine pairs by three residues in the twin CX3C motif. This is consistent with the view that a metal ion is present in a tetrahedral coordination. The conservation might be less expected if adjacent cysteine residues were engaged in separate disulfide bridges. However, a transient formation of disulfide bridges or a formation under specific conditions cannot be excluded. For instance, the bacterial chaperone Hsp33 contains four conserved cysteine residues that coordinate zinc or form disulfide bridges in vivo depending on the redox conditions in the cell (Jakob et al., 2000).

Tim13 is imported through the TOM complex

How are members of the family of small Tim proteins imported into mitochondria? In contrast to many other preproteins (Pfaller et al., 1989), Tim13 does not require the cytosol-exposed receptor domains of the TOM complex. On the other hand, Tim13 employs the TOM complex for translocation across the outer membrane. However, a stable interaction of Tim13 with the TOM translocase was not observed (data not shown). Tim13 may interact rather loosely with the TOM complex and randomly move in the TOM channel. A bidirectional diffusion of Tim13 through the TOM translocase is supported by our observation of the retrograde movement of Tim13 out of the IMS. This occurs when the zinc ions are removed from newly imported unassembled Tim13. The observed absence of high-affinity interactions with the TOM complex would remove the need for endergonic release reactions in subsequent steps of translocation. A diffusion-like translocation through the TOM channel without guidance of interaction sites would also explain why only relatively small proteins can use this pathway which most likely forms a single domain, either folded or unfolded.

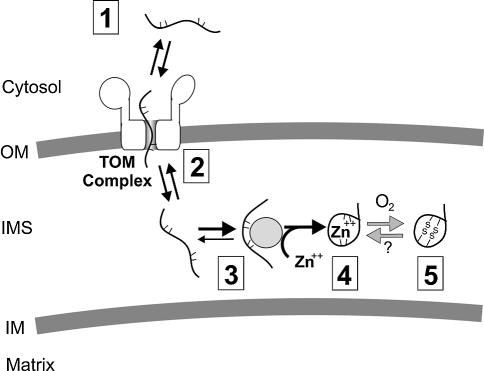

The ‘folding-trap’ model

The binding of zinc, like that of other cofactors, can strongly stabilize protein conformations and thereby lock proteins in a folded state (for review see Cox and McLendon, 2000). As we show here, zinc ions lock a core domain of Tim13 in a folded conformation. Metal binding by the thiol groups of the conserved cysteine residues is a prerequisite for stable folding of Tim13. We propose an import pathway of Tim13 in which folding of Tim13 and the acquisition of zinc ions are key requirements. Our results are consistent with the ‘folding-trap’ model depicted in Figure 8 (Simon et al., 1992). According to this hypothesis, small Tim proteins are imported into mitochondria by diffusion through the translocation channel of the TOM complex undergoing only weak interactions with its components (Figure 8, stage 2). Cofactor acquisition and folding of the imported Tim protein in the IMS then prevents backsliding into the TOM channel and traps the protein in the IMS (Figure 8, stages 3 and 4). This process is most likely facilitated by a zinc-transferring factor, as free zinc ions are virtually absent in the cell (Outten and O’Halloran, 2001). The same factor might donate zinc to other proteins such as Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase (Sod1). Recently a zinc-binding metallothionein which may participate in this process was identified in the IMS of mammalian mitochondria (Ye et al., 2001).

Fig. 8. Working model of Tim13 import. (1) Tim13 is initially present in the cytosol in an unfolded conformation. (2) Tim13 associates with the TOM complex without requiring cytosolic receptor domains; at this stage, Tim13 is not tightly bound and still exposes segments at the mitochondrial surface. (3) A zinc ion is incorporated into Tim13. This reaction is proposed to be mediated by a zinc-donating factor in the IMS, because free zinc ions are hardly present in the cell. (4) Acquisition of zinc stabilizes folding of Tim13 and prevents retrograde movement out of the mitochondria. (5) Oxidation of the cysteine residues in Tim13 would also warrant stable folding of Tim13. As the cysteine residues in endogenous Tim13 are present in a reduced state, this oxidation might occur only upon exposure to oxygen upon cell fractionation or reflect the presence of oxidized Tim13 under specific growth conditions.

The concept of trans side folding providing a driving force for import is supported by a number of observations: (1) prior to its import, Tim13 is present in an unfolded or loosely folded conformation and only adopts a stably folded structure after translocation; (2) modification or mutation of the free thiol groups which are essential for stable folding completely abrogates import of Tim13; (3) depletion of zinc ions which are necessary for the protease-resistant folding diminishes translocation into the IMS; (4) folded Tim13 is not competent for import across the outer membrane; (5) depletion of metal ions or modification of cysteine residues causes the release of already imported Tim13 from the IMS.

The model of a ‘folding trap’ as the driving force might not only apply to Tim13 and other small Tim proteins, but to the whole group of small IMS proteins including cytochrome c. Translocation by this mechanism would have the following characteristics. First, the proteins translocated are small and represent one folding unit. Secondly, their stable folding occurs only at the trans side of the membrane which is achieved by the acquisition of a cofactor in the IMS. Further dissection of the molecular mechanism of the import process of small IMS proteins will have to concentrate on the identification of zinc-donating factors in the IMS and on reconstitution of the process using purified components.

Materials and methods

Recombinant DNA techniques and plasmid constructions

Standard methods were used for DNA manipulations (Sambrook et al., 1989). The TIM13 gene was obtained by amplification of genomic yeast DNA and subcloned into pGEM4 (Promega, Madison, WI). The cysteine residues at positions 57, 61, 73 and 77 in the Tim13 sequence were replaced individually or in combinations by the use of PCR primers containing mismatches at the appropriate codons. Each of the TIM13 gene variants was verified by sequencing. For expression of the Tim13 derivatives as C-terminal fusions on MBP, Tim13 and the TimSSSS mutant were subcloned into the BamHI and HindIII sites of the vector pMAL-CRI (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) and transformed into in E.coli BL21(DE3)pLysS cells (Novagen, Madison, WI).

Yeast strains and cell growth

YPH499 and YPH501 were used as wild-type yeast strains (Sikorski and Hieter, 1989). The generation of the Δtim8/Δtim13 mutant was reported previously (Paschen et al., 2000). Yeast strains were cultivated on lactate medium (Herrmann et al., 1994). Mitochondria and spheroplasts were isolated as described (Herrmann et al., 1994). For preparation of spheroplasts DTT was omitted.

Protein purification procedures and determination of zinc

Tim13 fusion proteins were purified essentially as described for other Tim proteins (Hofmann et al., 2002), with the exception that the medium contained only 100 µM zinc acetate. When indicated 200 µM zinc acetate, which was about four times the concentration of recombinant protein, was added during the lysis but zinc was always absent from the washing and elution buffers. For preparation of the Tim13 protein used for import experiments, cultures were grown in zinc-free medium. MBP was removed from the fusion proteins by cleavage with factor Xa protease.

The zinc content of purified proteins was measured by ICP-AE spectroscopy with a VARIAN-VISTA instrument (Varian Inc., Palo Alto, CA). The protein content was determined by UV spectroscopy at 280 nm in 6 M guanidinium hydrochloride and 20 mM potassium phosphate pH 6.5 (Gill and von Hippel, 1989).

Protein import into isolated mitochondria

Radiolabeled precursor proteins were synthesized in the presence of [35S]methionine in reticulocyte lysate according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Promega). Import reactions into isolated yeast mitochondria (50 µg/reaction) were carried out in 0.6 M sorbitol, 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, 2 mM ATP, 2 mM NADH, 2 mM potassium phosphate, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 50 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.4 at 25°C when not indicated otherwise. Import was stopped by diluting the reaction 10-fold in ice-cold 0.6 M sorbitol and 20 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.4 with or without 50 µg/ml proteinase K. For hypotonic swelling of the outer membrane, mitochondria were resuspended in 20 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.4. Signals of radiolabeled proteins were detected by autoradiography on Biomax MR-1 films (Kodak, Rochester, NY) and quantified using a Pharmacia Image Scanner with an Image Master 1D Elite software package.

For import of chemical amounts, 1 µg of purified Tim13 or Tim13SSSS was dialysed against 6 M guanidinium hydrochloride, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 10 mM EDTA and 20 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.4 and diluted 100-fold into an import reaction containing 50 µg of Δtim8/Δtim13 mitochondria. For import of folded Tim13, the guanidinium hydrochloride was omitted. For depletion of metal ions, mitochondria were preincubated with 10 mM EDTA and 2 mM o-phenanthroline for 50 min at 0°C. In the control, the chelators were added directly before the import reaction to ensure chemical identity of the samples. To restore the zinc levels, metal-depleted mitochondria were layered onto 0.6 M sucrose and 40 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.4 containing either 2 mM EDTA or 10 µM zinc acetate. Following centrifugation for 15 min at 15 000 g, the mitochondria were resuspended in import buffer. The import of Tim13 was monitored by immunoblotting with Tim13-specific antiserum and quantified by densitometry.

Trypsin treatment of endogenous, imported and recombinant Tim13

For trypsin treatment of endogenous Tim13, 50 µg of mitochondria were incubated for 30 min in 15 µl of 20 mM HEPES–KOH pH7.4 and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol on ice. After a clarifying spin the resulting IMS fraction was treated with trypsin for 20 min on ice.

For trypsin treatment of imported Tim13, radiolabeled Tim13 was imported for 15 min into mitochondria as described above. The outer membrane was opened by hypotonic swelling. Then the sample was treated with 50 µg/ml trypsin for 20 min on ice.

For trypsin treatment of the MBP-Tim13 constructs, 0.2 µg of purified protein was incubated for 10 min in 30 µl 20 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.4 and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol with or without 10 mM EDTA and 2 mM o-phenanthroline or with 10 mM EDTA and 0.5 mM TPEN. Then trypsin was added to 0–50 µg/ml final concentration and the samples were incubated for 20 min on ice.

Modification of proteins

For modification of cysteine residues with NEM, radiolabeled proteins were incubated for 30 min at 4°C in the presence of 2 mM NEM in 100 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.4. Residual amounts of NEM were quenched by addition of 10 mM DTT. For control, the reaction was carried out in the presence of 10 mM DTT.

For modification of cysteine residues with AMS (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), 100 µg of spheroplasts were lysed in 70 µl of 0.1% TX100, 60 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.4 and 30 mM AMS. The samples were sonicated for 2 min in an ultrasonic bath and incubated in darkness for 2 h at room temperature. Proteins were precipitated by addition of 12% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and applied to SDS–PAGE. For the oxygen-deprived sample, the reaction buffer was degassed for 10 min using a PC 2001 Vario diaphragm vacuum pump (Vacuubrand, Wertheim, Germany) and then purged with nitrogen gas for 2 min. This procedure was repeated twice before addition of the spheroplasts. The modification reaction was carried out under a nitrogen atmosphere.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Benedikt Westermann, William Stafford and Andreja Vasiljev for stimulating discussion, Béatrice Fofou, Sandra Esser and Ilona Dietze for technical assistance and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft for financial support (He2803/2–2).

References

- Bauerfeind M., Esser,K. and Michaelis,G. (1998) The Saccharomyces cerevisiae SOM1 gene: heterologous complementation studies, homologues in other organisms, and association of the gene product with the inner mitochondrial membrane. Mol. Gen. Genet., 257, 635–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beers J., Glerum,D.M. and Tzagoloff,A. (1997) Purification, characterization, and localization of yeast Cox17p, a mitochondrial copper shuttle. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 33191–33196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox E.H. and McLendon,G.L. (2000) Zinc-dependent protein folding. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol., 4, 162–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran S.P., Leuenberger,D., Schmidt,E. and Koehler,C.M. (2002) The role of the Tim8p–Tim13p complex in a conserved import pathway for mitochondrial polytopic inner membrane proteins. J. Cell Biol., 158, 1017–1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diekert K., de Kroon,A.I., Ahting,U., Niggemeyer,B., Neupert,W., de Kruijff,B. and Lill,R. (2001) Apocytochrome c requires the TOM complex for translocation across the mitochondrial outer membrane. EMBO J., 20, 5626–5635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont M.E., Cardillo,T.S., Hayes,M.K. and Sherman,F. (1991) Role of cytochrome c heme lyase in mitochondrial import and accumulation of cytochrome c in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell Biol., 11, 5487–5496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill S.C. and von Hippel,P.H. (1989) Calculation of protein extinction coefficients from amino acid sequence data. Anal. Biochem., 182, 319–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haucke V., Ocana,C.S., Honlinger,A., Tokatlidis,K., Pfanner,N. and Schatz,G. (1997) Analysis of the sorting signals directing NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase to two locations within yeast mitochondria. Mol. Cell Biol., 17, 4024–4032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann J.M., Fölsch,H., Neupert,W. and Stuart,R.A. (1994) Isolation of yeast mitochondria and study of mitochondrial protein translation. In Celis,J.E. (ed.), Cell Biology: A Laboratory Handbook, Vol. 1. Academic Press, San Diego, CA, pp. 538–544. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann S., Rothbauer,U., Muhlenbein,N., Neupert,W., Gerbitz,K.D., Brunner,M. and Bauer,M.F. (2002) The C66W mutation in the deafness dystonia peptide 1 (DDP1) affects the formation of functional DDP1.TIM13 complexes in the mitochondrial intermembrane space. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 23287–23293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakob U., Eser,M. and Bardwell,J.C. (2000) Redox switch of hsp33 has a novel zinc-binding motif. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 38302–38310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T. and Ito,K. (1999) Respiratory chain strongly oxidizes the CXXC motif of DsbB in the Escherichia coli disulfide bond formation pathway. EMBO J., 18, 1192–1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehler C.M. (2000) Protein translocation pathways of the mitochondrion. FEBS Lett., 476, 27–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuenberger D., Bally,N.A., Schatz,G. and Koehler,C.M. (1999) Different import pathways through the mitochodrial intermembrane space for inner membrane proteins. EMBO J., 18, 4816–4822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister R., Mowday,B., Whelan,J. and Millar,A.H. (2002) Zinc-dependent intermembrane space proteins stimulate import of carrier proteins into plant mitochondria. Plant J., 30, 555–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louie G.V. and Brayer,G.D. (1990) High-resolution refinement of yeast iso-1-cytochrome c and comparisons with other eukaryotic cytochromes c. J. Mol. Biol., 214, 527–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nargang F.E., Drygas,M.E., Kwong,P.L., Nicholson,D.W. and Neupert,W. (1988) A mutant of Neurospora crassa deficient in cytochrome c heme lyase activity cannot import cytochrome c into mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem., 263, 9388–9394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neupert W. and Brunner,M. (2002) The protein import motor of mitochondria. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol., 3, 555–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobrega M.P., Bandeira,S.C., Beers,J. and Tzagoloff,A. (2002) Characterization of COX19, a widely distributed gene required for expression of mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 40206–40211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outten C.E. and O’Halloran,T.V. (2001) Femtomolar sensitivity of metalloregulatory proteins controlling zinc homeostasis. Science, 292, 2488–2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschen S.A., Rothbauer,U., Kaldi,K., Bauer,M.F., Neupert,W. and Brunner,M. (2000) The role of the TIM8-13 complex in the import of Tim23 into mitochondria. EMBO J., 19, 6392–6400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaller R., Pfanner,N. and Neupert,W. (1989) Mitochondrial protein import. Bypass of proteinaceous surface receptors can occur with low specificity and efficiency. J. Biol. Chem., 264, 34–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfanner N. and Geissler,A. (2001) Versatility of the mitochondrial protein import machinery. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol., 2, 339–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., Fritsch,E.F. and Maniatis,T. (1989) Molecular cloning. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Schricker R., Angermayr,M., Strobel,G., Klinke,S., Korber,D. and Bandlow,W. (2002) Redundant mitochondrial targeting signals in yeast adenylate kinase. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 28757–28764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski R.S. and Hieter,P. (1989) A system of shuttle vectors and host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics, 122, 19–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon S.M., Peskin,C.S. and Oster,G.F. (1992) What drives the translocation of proteins? Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 3770–3774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirrenberg C., Endres,M., Fölsch,H., Stuart,R.A., Neupert,W. and Brunner,M. (1998) Carrier protein import into mitochondria mediated by the intermembrane proteins Tim10/Mrs11p and Tim12/Mrs5p. Nature, 391, 912–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner H., Zollner,A., Haid,A., Neupert,W. and Lill,R. (1995) Biogenesis of mitochondrial heme lyases in yeast—import and folding in the intermembrane space. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 22842–22849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokatlidis K., Vial,S., Luciano,P., Vergnolle,M. and Clemence,S. (2000) Membrane protein import in yeast mitochondria. Biochem. Soc. Trans, 28, 495–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye B., Maret,W. and Vallee,B.L. (2001) Zinc metallothionein imported into liver mitochondria modulates respiration. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 2317–2322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]