Abstract

Proper 3′ end formation of the human pre-snRNAs synthesized by pol II requires the cis-acting 3′ box, although the precise function of this element has proved difficult to determine. In vivo, 3′ end formation is tightly linked to transcription. However, we have now been able to obtain transcription-independent 3′ box-dependent processing in vitro. This finally demonstrates that the 3′ end of pre-snRNAs is produced by RNA processing rather than by termination of transcription. The phosphorylated form of the C-terminal domain (CTD) of pol II activates the processing event in vitro, consistent with our previous demonstration of the role of the CTD in pre-snRNA 3′ end formation in vivo. In addition, we show that sequences upstream from the 3′ box of the U2 snRNA gene influence 3′ end formation both in vivo and in vitro.

Keywords: CTD/phosphorylation/pol II/snRNA/3′ processing

Introduction

The vertebrate U1, U2, U4 and U5 small nuclear (sn)RNA genes are transcribed by polymerase II (pol II) to yield short non-polyadenylated 3′-elongated precursors, which are specific substrates for cytoplasmic processing (see Huang et al., 1997). The mature snRNAs are re-imported into the nucleus, where they function in the processing of pre-mRNA in the form of ribonucleoprotein particles (snRNPs) (see Will and Lührmann, 2001). Efficient formation of snRNA precursors requires a 13–16 nucleotide (nt) cis-acting element named the 3′ box, located 9–19 nucleotides downstream of the 3′ end of the RNA-encoding region (Hernandez, 1985; Yuo et al., 1985; Hernandez and Lucito, 1988). A compatible pol II snRNA promoter is also required for proper 3′ end formation of pre-snRNAs, highlighting the tight link between transcription and the function of the 3′ box (Hernandez and Weiner, 1986; Neuman de Vegvar et al., 1986). Until now, it was unclear whether the 3′ box acts as a transcription terminator or an RNA processing element. Transcription terminates close to the 3′ box of the human U1 snRNA genes (Kunkel and Pederson, 1985; Cuello et al., 1999) and 3′ elongated Xenopus U1 or U2 snRNAs containing the 3′ box are not further processed after injection into Xenopus oocytes (Ciliberto et al., 1986), arguing in favour of a termination role for the 3′ box. However, we have shown that transcription of the human U2 snRNA gene continues for ∼800 nt beyond the 3′ box, suggesting rather that it directs RNA processing (Cuello et al., 1999; Medlin et al., 2003). In this case, 3′ end formation of vertebrate pre-snRNAs would resemble 3′ end formation of mRNAs, which occurs by cleavage of a larger precursor (see Dominski and Marzluff, 1999; Wahle and Rüegsegger, 1999). In addition, the first step of 3′ end formation of pol II-transcribed yeast snRNAs occurs by cleavage (see Allmang et al., 1999a; Zhou et al., 1999; Morlando et al., 2002), although no sequence homologous to the 3′ box is present.

We have recently shown that the C-terminal domain (CTD) of pol II plays a crucial role in linking transcription and 3′ end formation of human snRNAs (Medlin et al., 2003), as has been shown for mRNAs. The CTD of mammalian pol II comprises 52 tandem repeats of the heptad YSPTSPS and participates in both transcription of protein-encoding genes and processing of the transcribed RNAs. Phosphorylation of the CTD is also required for efficient activation of capping, splicing and cleavage/polyadenylation (see Prelich, 2002; Proudfoot et al., 2002). In vivo, inhibition of CTD kinases dramatically reduces 3′ box-dependent processing of pre-U2 snRNA, suggesting that the phosphorylated CTD also participates in this process (Medlin et al., 2003). We have therefore proposed that the CTD participates in the promoter dependence of pre-snRNA 3′ end formation and that the phosphorylated CTD interacts with pre-snRNA-specific factor(s) to activate co-transcriptional 3′ box-dependent RNA processing.

However, a definitive demonstration that the 3′ box directs RNA cleavage has been difficult to obtain. The low level of in vitro transcription obtained from pol II-dependent snRNA gene promoters has hampered studies using the coupled transcription/3′ end formation system described by Gunderson et al. (1990) and no uncoupled 3′ end formation system has been hitherto reported.

We therefore undertook to develop a tractable in vitro system to investigate the function of the 3′ box. After testing a wide range of conditions, we obtained accurate in vitro 3′ end formation of synthetic RNA substrates containing the 3′ box of the human U1 or U2 snRNA genes. Thus, the 3′ box can direct RNA cleavage in the absence of transcription and is therefore a bona fide RNA processing element. Following partial purification of the processing activity, we can show that the phosphorylated form of the pol II CTD activates 3′ box-dependent cleavage of the RNA in vitro. Furthermore, we find that sequences upstream from the 3′ box in the U2 snRNA gene are required for accurate and efficient 3′ end processing in vivo and in vitro.

Results

Synthetic RNAs containing the U1 3′ box are correctly processed in vitro

To analyse the molecular mechanism of 3′ end formation of snRNA precursors, we attempted to reproduce the in vivo event in vitro. Since our previous work suggests that the 3′ box is likely to be an RNA processing element (Cuello et al., 1999; Medlin et al., 2003), we undertook to set up an in vitro system where no ongoing transcription occurs, using a synthetic RNA containing a 3′ box as a substrate. Accordingly, we tested a range of synthetic RNAs, techniques for production of cell extract, incubation conditions and methods to analyse the products.

The 3′ box is sufficient to form the 3′ end of pre-snRNA (Hernandez, 1985; Yuo et al., 1985) and is generally considered to be the major element directing this process. However, the 3′ box tolerates some mutations or deletions with little or no effect on accuracy and efficiency of 3′ end formation (Ach and Weiner, 1987), and even complete deletion of the 3′ box does not always abolish 3′ end formation when other endogenous snRNA gene sequences are present (Hernandez, 1985; Yuo et al., 1985; Cuello et al., 1999; Medlin et al., 2003). These observations indicate that other sequence(s) within snRNA genes can also direct 3′ end formation of pre-snRNAs, albeit at a lower level. We therefore tested substrate RNAs where the U1 3′ box follows a 152 base pair (bp) non-snRNA sequence. These were produced from modified versions of the G-less cassette-containing plasmids already described by Gunderson et al. (1990), in which the 3′ box is the only snRNA gene sequence downstream of the promoter. In order to avoid a sharp transition to G-containing sequence just at the 3′ box, we have added a few G residues to the sequence upstream (see Materials and methods). Transcription is directed by a modified human U1 promoter in vivo and by the SP6 promoter in vitro (Figure 1A and B; U1 3′ box) and correctly processed RNA encoded by these templates will be approximately the same size as pre-U1 RNA. Any RNA subject to 3′ box-directed processing should not be further 3′ end modified, since the required signals are not present (see Huang et al., 1997). To test whether the 3′ box is functional in this context in vivo, we transfected the template with the U1 promoter into HeLa cells and analysed the products by RNase protection (Figure 1A). A major band mapping close to the expected size of processed RNA (see Hernandez, 1985; Patton and Wieben, 1987) represents ∼80% of detected RNA (Figure 1A, lane 1, and C). The remainder corresponds to non-processed, readthrough RNA. Similar percentages of proper 3′ end formation occur when the U1 3′ box flanks either histone or globin gene-derived sequences of similar sizes (Ramamurthy et al., 1996). When the 3′ box is absent, only readthrough RNA is detected (Figure 1A, lane 2). Importantly, transcription is abolished when the essential PSE element in the promoter is mutated (Figure 1A, lane 3). Thus, in this context the 3′ box is necessary and sufficient for proper 3′ end formation of RNA and similar synthetic RNAs are therefore legitimate substrates for in vitro processing reactions.

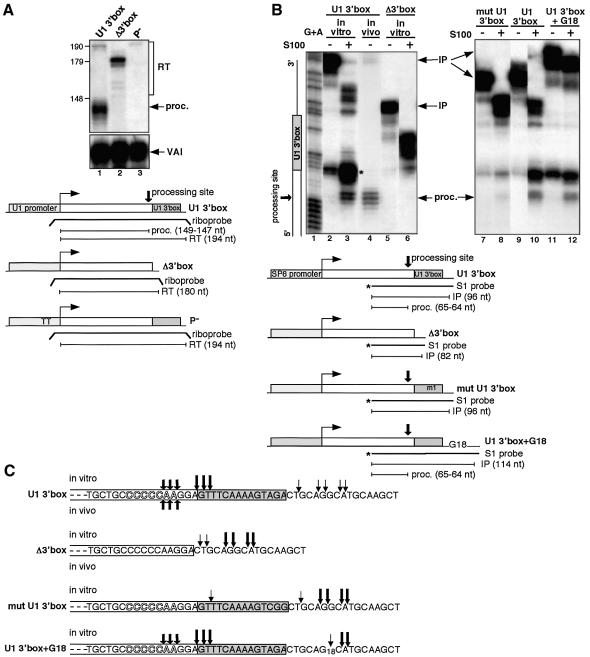

Fig. 1. Synthetic RNAs containing the U1 3′ box are correctly processed in vitro. (A) RNase protection of RNA from HeLa cells transfected with U1 3′ box, Δ3′ box or P– constructs. The positions of readthrough (RT), processed RNA (proc.) and transfection control VAI transcripts (VAI) are indicated on the right. Sizes in bp of a DNA marker are shown at the left. The relative positions of the riboprobes and the sizes of the processed or readthrough products are noted under the scheme of each construct. The same riboprobe was used for RNase protection of U1 3′ box RNA and P– RNA. (B) S1 nuclease analysis of synthetic RNAs with or without the U1 3′ box, with a mutated U1 3′ box or with U1 3′ box + G18, before and after incubation with S100. The RNA used and incubation with S100 is noted above the lanes. In lanes 2, 5, 7, 9 and 11, RNA was incubated in processing buffer with S100 replaced by buffer D. The positions of input (IP) and processed (proc.) RNAs are indicated on the right in this and subsequent figures. The relative positions of the S1 probes and the sizes of the input or processed RNA are noted under the scheme of each construct. The in vivo synthesized U1 3′ box RNA (lane 4) was the same RNA used in lane 1 in (A). The diagram on the left side of this and subsequent figures indicates the position of the 3′ box in the input RNA. A G + A DNA ladder (lane 1) was produced from the S1 probe used to analyse U1 3′ box RNA. For the asterisk, see the text. (C) Diagram of 3′ processing sites determined by analysis of in vitro (arrows above the sequence) or in vivo (arrows below the sequence) processed RNA in the presence or absence of the U1 3′ box, with mut U1 3′ box or with U1 3′ box + G18 RNA. The size of the arrow is proportional to the quantity of the detected product. Shadowed letters represent the positions of the 3′ end of human pre-U1 snRNAs produced in vivo (Hernandez, 1985; Patton and Wieben, 1987).

It proved difficult to readily identify any properly processed RNA products after direct incubation of radiolabelled in vitro synthesized RNA with cell extracts, due to the appearance of a complex ladder of ‘breakdown’ products (data not shown). However, S1 mapping with a 3′ labelled probe complementary to the synthetic RNA from 69 nt upstream to 13 nt downstream of the 3′ box sequence (Figure 1B) gives a simpler picture, and generates relatively short products, allowing accurate mapping of the 3′ end of the RNA. A range of extract preparation protocols (as described by Dignam et al., 1983; Shapiro et al., 1988; Dominski et al., 1995; or modifications of these) and incubation conditions, were tested. 3′ box-dependent processing was finally detected after incubating RNA substrates with a HeLa cell S100 fraction produced by the protocol of Shapiro et al. (1988), in conditions similar to those used for 3′ cleavage/polyadenylation of pre-mRNA in vitro (Moore and Sharp, 1985; Bienroth et al., 1993) (see Materials and methods). Some of the products detected after incubation of U1 3′ box RNA with this S100 fraction end 3–5 nt upstream of the 3′ box sequence (Figure 1B, lane 3, and C). These products are not detected when the RNA is incubated with buffer (Figure 1B, lanes 2 and 5) or when the 3′ box is absent (Figure 1B, lane 6). Furthermore, the amount of these products is severely reduced when two mutations known to affect the function of the 3′ box in vivo (Ach and Weiner, 1987) are introduced (Figure 1B, lanes 7 and 8, and C; mut U1 3′ box).

S1 analysis of U1 3′ box RNA extracted from HeLa cells (Figure 1A, lane 1) maps the 3′ ends produced in vivo to the same positions as these in vitro-produced RNAs: 3–5 nt upstream of the 3′ box (Figure 1B, compare lanes 3 and 4, and C). Importantly, the 3′ ends of these ‘correctly’ processed RNAs map within the range of distance upstream of the 3′ box observed for endogenous pre-U1 snRNA 3′ ends (Hernandez, 1985; Patton and Wieben, 1987) (Figure 1C).

In order to address whether the longer products, detected only in vitro (e.g. Figure 1B, lane 3), correspond to intermediates of the final 3′ processed RNA or to non-specific degradation products from an unrelated activity, we tested the effect of adding a row of 18 G residues downstream of the 3′ box (Figure 1B, lanes 11 and 12, and C; U1 3′ box + G18). This increases the distance from the 3′ box to the 3′ end of the RNA and long stretches of G residues have been shown to impede exoribonucleases (Wang and Kiledjian, 2002). The majority of upstream cleavage sites are also detected in the absence of the 3′ box (Figure 1B, compare lanes 3 and 6, and C) and are shifted upstream of the stretch of G residues (Figure 1B, compare lanes 10 and 12, and C), supporting the notion that they are the result of contaminating exonuclease activity. However, the product of the expected size is unaffected, suggesting that this is produced by an endonucleolytic event. The relatively strong bands mapping to the 5′ edge of the 3′ box (Figure 1B, lane 3, marked by an asterisk) are also unaffected (Figure 1B, compare lanes 10 and 12) and could therefore be processing intermediates, although a smaller amount of the same bands is detected when U1 3′ box RNA is incubated only with buffer (Figure 1B, lanes 2, 9 and 11). Intriguingly, only a few cleavage products map within the 3′ box itself, giving the appearance of a ‘footprint’ (Figure 1B, lane 3, and C).

These data show clearly that the 3′ box can independently direct accurate 3′ end RNA processing in vitro using cell extracts, indicating that it is a bona fide processing element. However, proper processing is relatively inefficient in vitro: in the experiment shown (Figure 1B) only 7% of the total input RNA has the same 3′ ends as produced in vivo after incubation for 13 h (Figure 1B, lane 3). The 3′ box itself appears to be refractory to cleavage, perhaps due to an unusual structure and/or protection by some of the proteins required for the processing reaction.

3′ box-dependent processing requires a divalent cation

To improve the efficiency of 3′ box-dependent processing in vitro, we investigated the requirement for divalent cations (Figure 2A). The efficiency of processing of U1 3′ box RNA is similar in buffer containing Mn2+ or Mg2+ (lanes 2 and 3), but is inefficient in the presence of Zn2+, Ca2+ or EDTA (lanes 4–6). Interestingly, production of the larger digestion products mapping to the 5′ end of the 3′ box is less dependent on divalent cations. Optimum activity is observed in the presence of 3 mM Mn2+ and increasing the concentration of Mn2+ further does not improve activity (Figure 2B). No products of the expected size are produced in the absence of the 3′ box, whatever the ion (Mn2+ or Mg2+) and concentration used (Figure 2C).

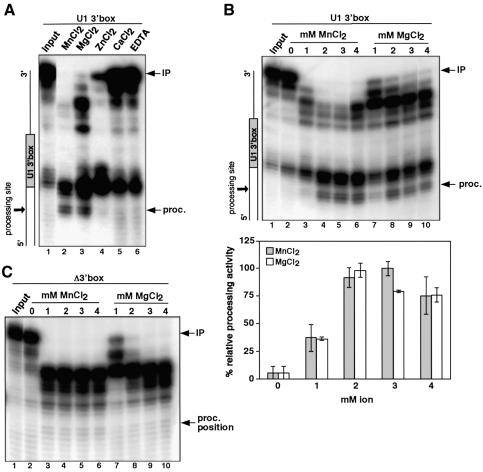

Fig. 2. 3′ box-dependent processing requires a divalent cation. (A) S1 nuclease analysis of U1 3′ box RNA incubated with S100 and different cations (lanes 2–5, 2 mM final concentration) or EDTA (lane 6, 5 mM final concentration), as noted above each lane. (B) S1 nuclease analysis of U1 3′ box RNA incubated with S100 in the presence of the concentration of Mn2+ (lanes 2–6) and Mg2+ (lanes 7–10) indicated in mM above each lane. The graph below represents the relative processing activity obtained in the presence of these concentrations of Mn2+ and Mg2+. The relative average activity of three independent experiments and standard deviation is calculated as a percentage of the processing activity obtained with 3 mM MnCl2 (maximum observed processing activity). (C) S1 nuclease analysis of Δ3′ box RNA incubated with S100 in the presence of the concentration of Mn2+ (lanes 2–6) and Mg2+ (lanes 7–10) indicated in mM above each lane. The hypothetical position of processed RNA (proc. position) is marked on the right.

Divalent cations may be required for binding of factor(s) to RNA and/or as a catalytic co-factor (see Schoenberg and Cunningham, 1999). Importantly, the products mapping to the 5′ end of the 3′ box have a different requirement for divalent cations and processing must therefore occur in at least two distinct steps if these are precursors to the final, properly processed RNA.

Partial purification of the 3′ box-dependent processing activity

To achieve a higher level of 3′ box-dependent processing, we attempted to purify and concentrate the factors responsible. The processing activity does not bind to either Heparin– or Q–Sepharose at 0.1 M KCl but binds efficiently to SP–Sepharose at this salt concentration and elutes between 0.3 and 0.4 M KCl. Active S100 was sequentially applied to Heparin–, Q– and SP–Sepharose, and SP-bound proteins eluted with steps of increasing KCl concentration (Figure 3A). This procedure results in an ∼600-fold purification of the processing activity (Table I).

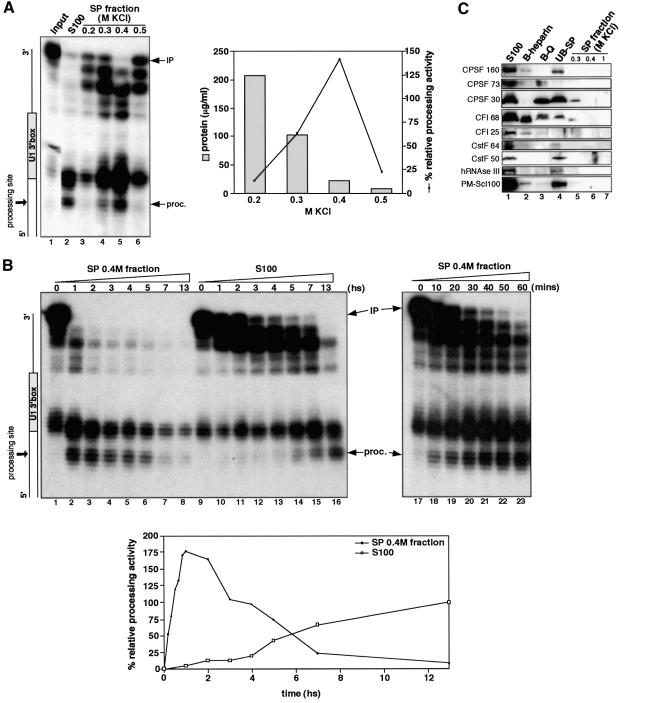

Fig. 3. Partial purification of the 3′ box-dependent processing activity. (A) S1 nuclease analysis of U1 3′ box RNA incubated with S100 or with different fractions eluted from SP–Sepharose by the KCl concentration noted above the lane. The graph on the right represents the relative processing activity and the protein concentration of the different SP fractions. The relative processing activity is calculated as a percentage of the processing activity obtained with S100. (B) S1 nuclease analysis of U1 3′ box RNA incubated with either the SP 0.4 M KCl fraction (lanes 1–8 and 17–23) or with S100 (lanes 9–16) for the incubation time indicated in hours (hs) or in minutes (mins) above each lane. The graph below represents the relative processing activity of the SP 0.4 M KCl and S100 fractions at different time points calculated as a percentage of the processing activity obtained with S100 after 13 h incubation. (C) Detection of known RNA cleavage factors in S100 and purification fractions by western blot. The factors detected by the antibodies used are indicated on the left. The amount of each fraction corresponding to 12.5 µl of input S100 (lane 1) was loaded onto a 6% SDS–polyacrylamide gel. B-heparin (lane 2) and B-Q (lane 3) represent the proteins binding to heparin– and Q–Sepharose, respectively. UB-SP (lane 4) represents the proteins that do not bind to SP–Sepharose.

Table I. Partial purification of the 3′ box-dependent processing activity.

| Step | Protein(mg) | Activity(U)a | Specific activity(U/mg) | Yield(%) | Purification(fold) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S100 | 9.5 | 4.6 | 0.5 | 100 | |

| Heparin | 8.3 | 6 | 0.7 | 135 | 1.4 |

| Q–Sepharose | 6.5 | 6 | 0.9 | 135 | 1.8 |

| SP–Sepharose | 0.023 | 6.5 | 283 | 142 | 566 |

aProcessing activity was measured by incubation of U1 3′ box RNA and is expressed as a percentage of input RNA processed.

In the experiment shown in Figure 3B, processing products were detected as early as 10 min and the maximum amount of properly processed RNA was produced after 1 h with the SP 0.4 M KCl fraction (Figure 3B, lanes 17–23), compared with 13 h for the S100. The maximum was also increased by ∼2-fold (Figure 3B), indicating that partial purification both increases the amount of processed RNA detected and speeds up the reaction. However, it appears that processed RNA is progressively degraded (possibly by exonucleases) after 2 h (Figure 3B, lanes 1–8). Thus, the amount of processed RNA detected results from a kinetic balance between the 3′ processing activity and degradation. This degradation might result from, for example, 3′→5′ exoribonuclease activity of the human exosome subcomplex present in HeLa cell S100 (Allmang et al., 1999b).

In order to determine whether any known RNA cleavage factors are involved in 3′ end formation of pre-snRNAs, we carried out western blot analysis on the various fractions with antibodies to subunits of several pre-mRNA cleavage/polyadenylation factors (Figure 1C). We also assayed the fractions for enrichment of hRNase III (Wu et al., 2000) and PM-Scl100 (Allmang et al., 1999b), since these are homologues of yeast RNAse III (Rnt1p and Pac1p) and Rrpb6p, respectively, that have been shown to participate in 3′ processing of yeast pre-snRNAs, rRNAs or snoRNAs (see Will and Lührmann, 2001; Butler, 2002; Conrad and Rauhut, 2002) (Figure 1C). None of these factors is enriched in the most active SP 0.4 M KCl fraction, suggesting that one or more novel factors are required for 3′ box-dependent processing.

Our results demonstrate that it is possible to increase accurate processing by partial purification and suggest any overlap in the factors used for 3′ end formation of vertebrate pre-snRNAs and those of vertebrate pre-mRNAs or of yeast pre-snRNAs is limited. The ‘footprint’ over the 3′ box is still apparent after purification, suggesting that 3′ box-binding proteins co-purify with the processing activity. Further characterization of the 3′ processing activity was undertaken using the more efficient, partially purified fraction.

The CTD of pol II activates 3′ box-dependent processing of pre-snRNAs in vitro

Using the polymerase complementation system set up by Gerber et al. (1995) we have shown that the CTD of pol II is required for the function of the U2 3′ box. In addition, treatment of cells with CTD kinase inhibitors prevents proper U2 snRNA 3′ end formation. Accordingly, we suggested that phospho-CTD participates in pre-snRNA 3′ end processing (Medlin et al., 2003). We have therefore investigated the role of the CTD and its phosphorylation status in the U1 3′ box-dependent processing in vitro.

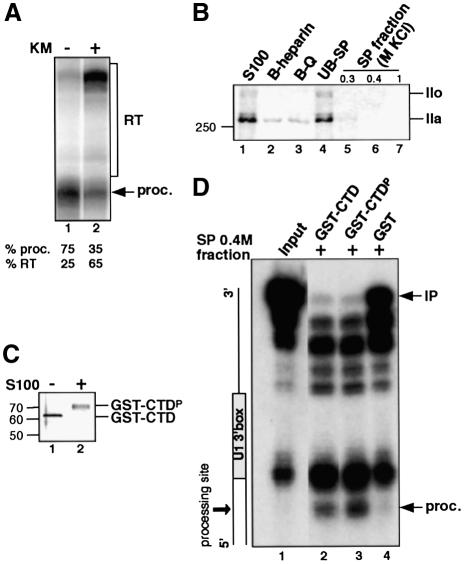

First, we tested whether the CTD kinase inhibitor 8-(methylthio)-4,5-dihydrothieno[3′,4′:5,6]benzoisoxazole-6-carboxamide (KM05283) inhibits 3′ end formation of transcripts from templates containing the U1 3′ box, as we found for the U2 3′ box (Medlin et al., 2003). HeLa cells transfected with the U1 3′ box construct were treated for 4 h with KM05283 and the RNA was analysed by RNase protection (Figure 4A). Treatment causes an increase in readthrough from 25% in the untreated cells to 65% in the treated cells (Figure 4A, lanes 1 and 2) indicating that 3′ box function is inhibited. We also carried out western blot analysis on the active processing extracts with an antibody recognizing the N-terminus of the large subunit of pol II (Figure 4B). Both the IIo (hyperphosphorylated) and IIa (hypophosphorylated) isoforms of pol II are detected in the HeLa cell S100 fraction with a major proportion of pol IIa (Figure 4B, lane 1). The pol II present in the S100 does not bind readily to any of the resins used (Figure 4B, lanes 2–4), although a small amount of pol IIa is detected in the 0.3 M KCl SP–Sepharose eluted fraction (Figure 4B, lane 5). Neither pol IIo or pol IIa is detected in the fractions eluted with 0.4 and 1 M KCl (Figure 4B, lanes 6 and 7).

Fig. 4. The CTD of pol II activates 3′ box-dependent processing of pre-snRNAs in vitro. (A) RNase protection of U1 3′ box RNA extracted from HeLa cells before and after treatment with 100 µM kinase inhibitor (KM05283). Positions of readthrough (RT) and processed RNA (proc.) are indicated on the right. The percentage of processed RNA (% proc.) and readthrough RNA (% RT) is indicated under each lane. Cells were untreated (lane 1) or treated with KM05283 (KM) for 4 h prior to harvesting (lane 2). (B) Detection of pol II in S100 and purification fractions by western blot. The positions of pol IIa (hypophosphorylated) and pol IIo (hyperphosphorylated) are indicated on the right and size marker in kDa on the left. The gel was loaded as described in Figure 3C. (C) GST–CTD phosphorylated by incubation with S100. GST–CTD (lane 1) was incubated for 4 h with S100 (lane 2). The size of protein markers is indicated in kDa on the left. (D) S1 nuclease analysis of U1 3′ box RNA incubated with the SP 0.4 M KCl fraction with addition of 10 ng of GST–CTD (lane 2), GST–CTDP (lane 3) or GST alone (lane 4).

To determine the effect of the CTD on processing, GST–CTD (with the CTD unphosphorylated or phosphorylated) was added to the in vitro processing reaction. We have used a fusion protein containing 29 heptapeptide repeats, since we have shown that 25 repeats is sufficient to allow a high level of processing in vivo (Medlin et al., 2003). Figure 4C shows a protein gel of the GST–CTD before (lane 1) or after (lane 2) incubation with S100 to allow complete phosphorylation (see Materials and methods). To maximize the potential effect of the CTD on 3′ processing activity we added one-quarter of the normal processing activity and incubated for only 1 h. Addition of non-phosphorylated CTD increases processing by ∼2-fold (Figure 4D, compare lanes 2 and 4) and phospho-CTD by ∼4-fold (Figure 4D, lane 3). These results indicate that the CTD activates processing and it is more efficient when phosphorylated, as was observed for pre-mRNA 3′ cleavage in vitro (Hirose and Manley, 1998). However, we cannot rule out the possibility that some phosphorylation of the CTD occurs during incubation. Addition of either form of CTD had no effect on the efficiency of processing using either S100 or the SP 0.3 M KCl fraction (data not shown), probably due to the presence of a saturating amount of pol II in these fractions. Addition of the CTD also activates production of the larger products, which may indicate that the activity of the ‘contaminating’ exonucleases is coupled to transcription by pol II in vivo. However, differential activation by phospho-CTD is specific for the reaction producing properly processed RNA (Figure 4D, compare lanes 2 and 3).

Taken together, our data indicate that the CTD activates 3′ box-dependent processing in vitro and this activity is further enhanced when the CTD is phosphorylated. This is consistent with our in vivo data showing that the CTD is involved in the 3′ processing of pre-U2 snRNA and strongly supports our proposal that CTD kinase inhibitors affect pre-snRNA 3′ end formation through inhibition of CTD phosphorylation (Medlin et al., 2003; Figure 4A).

The activity of the U2 3′ box is influenced by an upstream sequence in vivo and in vitro

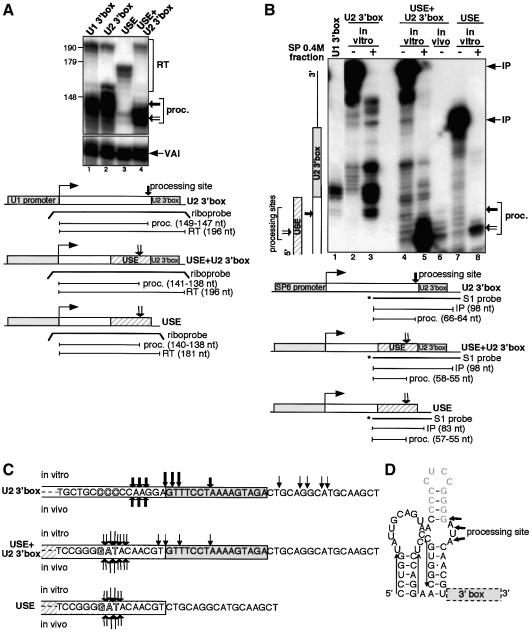

The 3′ boxes of the U1 and U2 genes are similar but not identical. In order to test whether these are interchangeable, we have replaced the U1 3′ box with the U2 3′ box in the U1 3′ box template and tested processing in vivo and in vitro (Figure 5). As noted above, accurate 3′ end formation still occurs in some U2 gene constructs in the absence of the 3′ box (Hernandez, 1985; Yuo et al., 1985; Cuello et al., 1999; Medlin et al., 2003), implicating other gene sequences in this process. In the U2/Globin construct used by Medlin et al. (2003), most of the RNA encoding sequences is replaced by β-globin gene sequences. However, a readily detectable amount of RNA with a proper 3′ end is still produced in the absence of the 3′ box (26% of the amount produced in the presence of the 3′ box). This construct contains 53 bp of U2 gene sequence immediately upstream from the 3′ box and we have tested this sequence (designated USE) alone or in conjunction with the U2 3′ box for the ability to direct accurate processing in vivo and in vitro (USE and USE + U2 3′ box, respectively; Figure 5). The U2 3′ box, USE and USE + U2 3′ box templates were transfected into HeLa cells and the RNA mapped by RNase protection (Figure 5A). The U2 3′ box alone directs 3′ end formation at the same positions as the U1 3′ box (Figure 5A, compare lanes 1 and 2), indicating that the differences between them do not affect the position of processing sites. However, the 3′ ends of endogenous pre-U2 snRNA map a few nts further upstream of the 3′ box (Yuo et al., 1985; Figure 5C). The 3′ box and USE together direct 3′ end formation to sites overlapping those mapped for endogenous pre-U2 snRNA (Yuo et al., 1985; Figure 5A, lane 4, and C). 3′ end formation is relatively inefficient in the presence of the USE alone, but occurs at the same site as in conjunction with U2 3′ box (Figure 5A, compare lanes 3 and 4). These results suggest that the signal for 3′ end formation of pre-U2 snRNA is bipartite, with the USE acting as a positioning element.

Fig. 5. The activity of the U2 3′ box is influenced by an upstream sequence element in vivo and in vitro. (A) RNase protection of RNA from HeLa cells transfected with constructs containing either the U1 or U2 3′ box, the U2 3′ box and the USE or the USE. The positions of readthrough (RT), processed RNA (proc.; closed arrow for the 3′ box-dependent processing site and open arrow for the USE-dependent processing site) and VAI transcripts (VAI) are indicated on the right. The relative positions of the riboprobes and the sizes of the readthrough or processed products are noted under the scheme of each construct. (B) S1 nuclease analysis of synthetic RNAs containing the U1 3′ box (lane 1), the U2 3′ box (lanes 2 and 3), the USE and the U2 3′ box (lanes 4 and 5) or the USE (lanes 7 and 8), with and without incubation with the SP 0.4 M KCl fraction respectively. The arrows at the right indicate the positions of processed products as described in (A). The relative positions of the S1 probes and the sizes of the input or processed RNA are noted under the scheme of each construct. The in vivo transcribed USE + U2 3′ box RNA (lane 6) was the same RNA used in lane 4 in (A). (C) Diagram of 3′ processing sites determined by analysis of in vitro (arrows above the sequence) or in vivo (arrows below the sequence) processed RNA in the presence of the U2 3′ box, the USE and the U2 3′ box or the USE. The size of the arrow is proportional to the quantity of the detected product. Shadowed letters represent the positions of the 3′ end of human pre-U2 snRNAs produced in vivo (Yuo et al., 1985). (D) Computer-putative secondary structure of the USE predicted by mfold v. 3.1 (Mathews et al., 1999) with a ΔG of –15 kcal. The U2 3′ box position is indicated by a dashed box. The long arrows above the sequence represent nts included in the stem–loop IV of mature U2 snRNA (Reddy et al., 1981) and the 3′ terminal minihelix is in grey (Mougin et al., 2002). The processing sites observed in vivo and in vitro in the presence of the USE are indicated by short arrows.

For in vitro analysis, synthetic RNA produced from these constructs was incubated with the SP 0.4 M KCl fraction and analysed by S1 mapping (Figure 5B). Approximately the same amount of U2 3′ box RNA is processed as U1 3′ box RNA (10% of the total input RNA) and a similar pattern of products is generated, apart from an extra cleavage within the U2 3′ box (Figure 5B, compare lanes 1 and 3, and C). The shortest U2 3′ box-specific products map 3–5 nt upstream of the 3′ box and do not correspond to the expected 3′ ends for pre-U2 snRNA (Yuo et al., 1985; Figure 5C). In contrast, RNA containing both the USE and the U2 3′ box is very efficiently processed in vitro (68% of the total input RNA) to products with the same 3′ ends produced in vivo and as mapped for endogenous pre-U2 snRNA (Figure 5B, compare lanes 5 and 6, and C). The same 3′ ends are produced when the USE is present although processing is less efficient (12% of the total input RNA) (Figure 5B, lane 8, and C) indicating that the two elements work synergically in vitro.

The USE contains the 3′ half of stem–loop IV of U2 snRNA (Reddy et al., 1981), which has already been implicated in 3′ end formation of precursors. Indeed, deletion of this region affects 3′ end formation of human U2 snRNA precursors synthesized in Xenopus oocytes (Yuo et al., 1985). The USE also contains the 3′ terminal minihelix recently identified in the pre-U2 snRNA structure and suggested to play a role in 3′ end formation of pre-U2 snRNA (Mougin et al., 2002). Interestingly, a computer-putative secondary structure of the USE contains the minihelix with the processing sites located within an unpaired bulge (Figure 5D).

These results show that it is possible to obtain very efficient and accurate 3′ box-dependent RNA processing in vitro using a partially purified processing activity, but only when the U2 USE is present upstream of the U2 3′ box. Furthermore, the secondary structure of the USE may be critical to ensure the accuracy and/or efficiency of cleavage.

Discussion

The 3′ end of vertebrate snRNAs is produced in several distinct steps. First, a precursor with a 3′ extension of up to 20 nt is produced and this is a specific substrate for exonucleolytic trimming to generate the mature 3′ end (see Huang et al., 1997). The 3′ box, first described as a conserved element by Mattaj and Zeller (1983), plays a key role in production of the precursor (Hernandez, 1985; Yuo et al., 1985). However, it has been difficult to determine whether the 3′ box directs production of the precursor by transcription termination or RNA processing. Our demonstration here that the 3′ box of either the U1 or U2 gene can direct 3′ end processing of a non-snRNA-derived RNA in vitro indicates that this element is a bona fide RNA processing element that can function autonomously. Thus, the primary 3′ ends of all vertebrate RNAs synthesized by pol II are produced by RNA processing directed by a cis-acting element(s) rather than by termination.

Why was 3′ box-dependent processing difficult to detect in vitro?

The type of template used, the method of extract production and the incubation conditions all proved critical to detection of the processing activity. For example, in our initial experiments, substrate RNAs containing mainly wild-type snRNA sequences were rapidly degraded (data not shown). This might explain why this is the first demonstration of 3′ box-dependent processing in vitro. Although the U1 3′ box-dependent processing is accurate, the reaction is relatively inefficient in unpurified extract, requiring long incubation times. Thus, processing factors may not be effectively extracted from the cells and/or may be very labile. Alternatively, inhibitors and/or non-specific nucleases may interfere with the reaction. Relevant to this, we find that the processed RNA is turned over relatively rapidly even after the processing activity is partially purified (Figure 3). It is therefore possible that the RNA substrate containing relatively few G residues is more resistant to turnover than others we tried. Processing may also be inefficient because it is uncoupled from transcription. Coupling of processing and transcription appears to be obligatory in vivo since RNA containing the 3′ box is not processed when injected into oocytes (Ciliberto et al., 1986) and readthrough RNAs are not processed to the mature form when transcription is blocked (Lobo and Marzluff, 1987). In addition, efficient recognition of the 3′ box is dependent on initiation of transcription from an snRNA promoter (Hernandez and Weiner, 1986; Neuman de Vegvar et al., 1986), and the CTD of pol II is required (Medlin et al., 2003). In accordance with this, we find that the CTD activates 3′ end formation in vitro. Moreover, phosphorylation of the CTD is required for full activation, supporting our proposal that kinase inhibitors (e.g. DRB and KM05283) exert their effect on 3′ processing through inhibition of CTD phosphorylation (Medlin et al., 2003). Thus, the phospho-CTD is likely to play a key role in coupling initiation with processing and may interact specifically with processing factor(s).

Both in vivo and in vitro, the U2 3′ box directs 3′ end formation a few nucleotides closer to the 3′ box than observed for endogenous pre-U2 snRNA. In contrast, the U2 USE alone directs production of 3′ ends mapping at the expected sites. Together, these elements act synergically to constitute a strong processing signal directing in vitro 3′ end formation at the same sites seen in the endogenous U2 snRNA gene transcripts. The USE appears to help position cleavage and/or stabilize processed RNA both in HeLa cells and in vitro, and the secondary structure of this element may be functionally important. No sequence similar to the U2 USE is present in the U1 gene and the U1 3′ box alone is sufficient for accurate processing. In addition, very little properly processed RNA is detected from U1 templates when the 3′ box is deleted (Hernandez, 1985) suggesting that a USE-like sequence is not present in the U1 gene.

3′ processing of vertebrate pol II transcripts: variations on a theme?

We favour the notion, supported by the results presented in Figure 1B, that pre-snRNA 3′ ends are produced by a 3′ box-dependent endonuclease, in analogy to pre-mRNA 3′ processing. We failed to detect a 3′ cleavage product after incubation of radiolabelled USE + U2 3′ box RNA with the active SP 0.4 M KCl processing fraction although the correctly processed 5′ product is readily detected (unpublished observations). However, this may be due to rapid degradation of the uncapped 3′ cleavage product. The structure of the bipartite processing element of the U2 gene, with the USE upstream and the 3′ box downstream of the cleavage site, is reminiscent of the 3′ end processing signals found in mRNA genes. The cleavage/polyadenylation factors CstF and CPSF individually interact weakly with processing signals on either side of the cleavage site but these interactions increase when both factors are present (see Wahle and Rüegsegger, 1999; Proudfoot et al., 2002). In addition, both factors may be required to define the cleavage site. Similarly, in formation of the 3′ end of histone mRNA, SLBP interacts with the stem–loop structure upstream of the cleavage site to stabilize association of U7 snRNP with the purine-rich downstream element to allow accurate and efficient processing (see Dominski and Marzluff, 1999). The USE and U2 3′ box may both be contacted directly by processing factors in a similar fashion to ensure accurate and efficient processing of snRNA gene transcripts, and the ‘footprint’ over the 3′ box may be due to protection from digestion by an interacting protein(s).

Interestingly, in common with our in vitro processing activity, the yeast RNase III homologues (Pac1p and Rnt1p) require divalent cations for activity (Rotondo and Frendewey, 1996; Lamontagne and Elela, 2001), while 3′ end cleavage of pre-mRNAs does not (Moore and Sharp, 1985; Gick et al., 1986). However, Rnt1p recognizes specific stem–loop structure within the 3′ extension of yeast pre-snRNAs (see Conrad and Rauhut, 2002) and the 3′ box or USE sequences do not correspond to any known RNase III target sequences. In addition, neither the human RNase III homologue (hRNase III; Wu et al., 2000) nor the human Rrpb6p homologue (PM-Scl100; Allmang et al., 1999b) is enriched in our most active SP 0.4 M KCl processing fraction, arguing against a common mechanism for formation of the 3′ ends of human and yeast pre-snRNAs. We also failed to find evidence for a significant overlap of human pre-mRNAs cleavage/polyadenylation and pre-snRNAs processing factors.

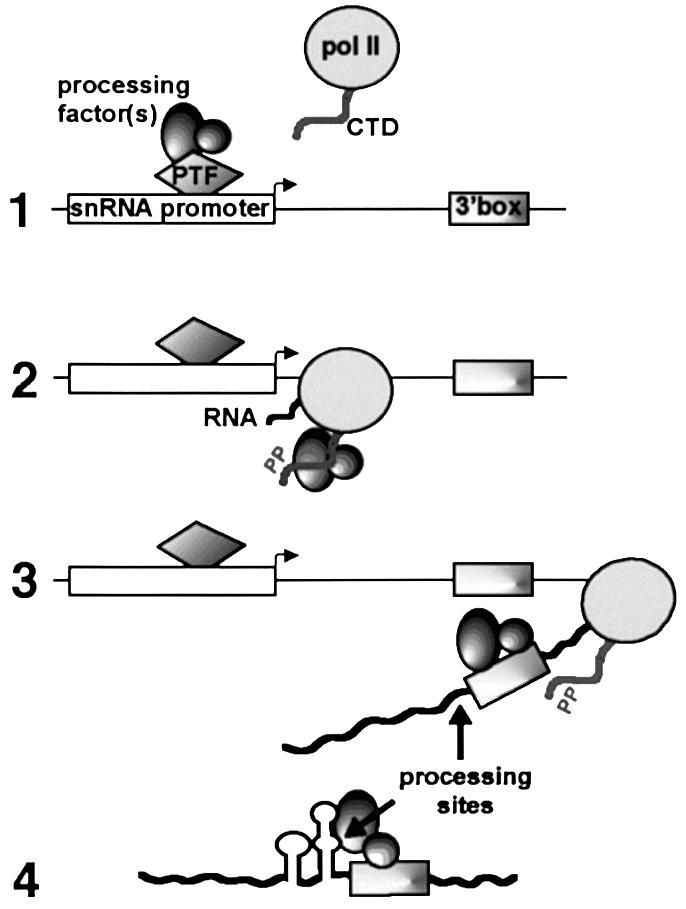

Connecting transcription and 3′ processing ofpre-snRNAs

This demonstration that the 3′ ends of pre-snRNAs are produced by 3′ box-dependent RNA processing that is activated by phospho-CTD supports our earlier model for the link between transcription and 3′ end formation (summarized in Figure 6). The promoters of pol II-transcribed snRNA genes are characterized by a PSE sequence recognized by the snRNA gene-specific factor PTF/PBP/SNAPc (see Hernandez, 2001). It is therefore possible that promoter-specific processing involves interactions, direct or indirect, between PTF and a processing factor(s) at initiation. Subsequent phosphorylation of the CTD could allow the processing factors to interact instead with the transcribing RNA polymerase, facilitating their delivery to newly synthesized RNA containing the 3′ box. In addition, our in vitro experiments indicate that phospho-CTD acts as a processing co-factor to promote the functional association between factors and RNA and/or activate directly the cleavage. Thus, initiation of transcription and 3′ end processing are coupled through the CTD in pre-snRNA as in pre-mRNA genes, but involve different cis-acting elements and trans-acting processing factor. Additional elements upstream of the 3′ box may ensure the accuracy of the cleavage reaction by interacting with the 3′ end-processing machinery.

Fig. 6. How promoter-dependent association of processing factor(s) with the phosphorylated CTD might activate 3′ box-dependent RNA processing. (1) A snRNA-specific 3′ processing factor(s) interacts with snRNA gene promoter-specific factors (e.g. PTF) before recruitment of pol II. (2) The processing factor(s) associate with the CTD after phosphorylation (by e.g. CDK7) and travel with the polymerase until transcription of the 3′ box. (3) Factors are downloaded to interact with the RNA and to promote cleavage upstream of the 3′ box. (4) In U2 snRNA gene transcripts, the additional USE adopts a secondary structure that allows interaction with factor(s) to reposition the cleavage site and/or stabilize the cleavage product.

Materials and methods

DNA constructs

The U1 3′ box construct containing a modified human U1 promoter was prepared by PCR from the pSG611 construct (Gunderson et al., 1990), which corresponds to human U1 promoter fused to a G-less cassette. In the U1 3′ box template, the DSE sequence is replaced by an inverted repeat of ATTTGCAT 23 bp upstream of the PSE, the five Cs located between +184 and +188 are replaced by six Cs, the A at +182 and the G at +189 are replaced by a T and A respectively, bases +171, +174, +180 and +183 were replaced by Gs and the sequence between +86 to +131 is replaced by CCTT. The final construct was cloned into pUC19 using the EcoRI and HindIII sites. In the Δ3′ box template (Figure 1A) the sequence corresponding to the U1 3′ box-GTTTCAAAAGTAGA is deleted. The P– construct (Figure 1A) was constructed in the same way as the U1 3′ box construct using pSGCCTT (Gunderson et al., 1990) as the PCR template. In the mut U1 3′ box template, the 3′ box is mutated in GTTTCAAAAGTCGG and in the U1 3′ box + G18 template, 18 G residues were introduced downstream of the 3′ box. The U2 3′ box construct (Figure 5A) was prepared from the U1 3′ box construct by PCR to replace the U1 3′ box sequence with the U2 3′ box-GTTTCCTAAAAGTAGA. In the USE + U2 3′ box and USE constructs, 59 bp of the U2 3′ box or Δ3′ box templates are replaced by the 53 bp upstream the 3′ box in the U2 gene and a BamHI site.

The EcoRI–HindIII fragments were cloned into pGEM4 to make riboprobes for U1 3′ box, Δ3′ box and U2 3′ box RNA (Figures 1A and 5A). To synthesize riboprobes for USE + U2 3′ box and USE RNA (Figure 5A), the StuI–HindIII fragments were subcloned into pGEM4. To produce synthetic RNA, the promoter region in the pGEM4 U1 3′ box, Δ3′ box, mut U1 3′ box, U1 3′ box+G18, U2 3′ box, USE + U2 3′ box and USE constructs was deleted using the EcoRI site in the vector and the BglII site 7 bp upstream from the U1 transcription start site.

In vitro RNA synthesis and in vitro processing

Capped RNA used as substrate for the in vitro processing reaction was synthesized from the HindIII-linearized DNA templates by SP6 in the presence of a 7-methyl-G cap analogue (Amersham). After synthesis, RNA substrates were purified from a 6% polyacrylamide–8 M urea gel, phenol/chloroform extracted and ethanol precipitated.

HeLa cell S100 extract was prepared according to Shapiro et al. (1988), dialysed overnight against 20 vol. of buffer D (Dignam et al., 1983), frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80°C in small aliquots. Processing reactions were usually carried out with 0.1 pmol RNA in 25 µl containing 50% of HeLa cell S100 or purified fraction with a final concentration of 10 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 50 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, 20 mM creatine phosphate, 3 mM MnCl2, 2.5% PVA, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM ATP and 20 ng/µl tRNA. Reactions were incubated at 30°C for 13 h (Figures 1B and 2), 7 h (Figure 3A) or 2 h (Figure 5B), and stopped by adding 125 µl of stop solution (0.5% SDS, 0.3 M NaOAc, 50 µg tRNA, 1 mM EDTA). RNA was extracted twice by phenol/chloroform, and ethanol precipitated. RNA was then annealed overnight at 47°C to the S1 probe and S1-digested at 37°C for 1 h. The products were analysed on 6% polyacrylamide–8 M urea gel and signals were quantitated using a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager. The amount of processed product is expressed as a percentage of the total input RNA. To prepare S1 probes (Figures 1B and 5B), an EarI–PvuII fragment of each construct in pGEM4 was 3′ end-filled with radiolabelled [α-32P]dGTP and purified on a 6% polyacrylamide–8 M urea gel.

For the purification shown in Table I, 9.5 mg of HeLa cell S100 was loaded onto 0.5 ml Heparin–Sepharose resin at 0.1 M KCl. The unbound fraction was loaded onto 0.3 ml Q–Sepharose resin and the unbound fraction from this step was loaded onto 0.3 ml SP–Sepharose resin. The bound proteins were step-eluted with 0.2–1 M KCl (Figure 3A). Proteins bound to Heparin– and Q–Sepharose were eluted with 1 M KCl. The processing activity was quantitated as above after S1 analysis of U1 3′ box RNA incubated with S100 or purified fractions and the protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay.

Transfections and steady state RNA analysis

Transfections of HeLa cells and subsequent RNA extractions were carried out as described previously (Medlin et al., 2003). Steady state RNA was analysed by RNase protection as outlined in Cuello et al. (1999). Riboprobes were made by T7 after digestion with StuI that cuts 39 bp upstream from the start of the U1 3′ box, Δ3′ box and U2 3′ box inserts or with EcoRI that cuts 76 bp upstream of the USE and USE + U2 3′ box inserts.

For the experiment shown in Figure 4A, HeLa cells were treated for 4 h with 100 µM of the kinase inhibitor KM05283 before harvesting cells as described by Medlin et al. (2003).

Production and phosphorylation of GST–CTD

The construct encoding 29 heptapeptide repeats fused to GST was a kind gift from Sasha Akoulitchev. The GST–CTD fusion protein was expressed as described by McCracken et al. (1997). In vitro phosphorylation of GST–CTD was performed as previously described (Hirose and Manley, 1998) with modifications: 100 µl of S100 fraction was incubated with 2 µg of GST–CTD for 4 h at 30°C in processing buffer.

Western blotting

Western blotting (Figure 4B) was carried out as outlined by Medlin et al. (2003). Anti-CPSF 73, -CPSF 30, -CFI 68 and -CFI 25 were kindly provided by Professor Walter Keller and were used as indicated by de Vries et al. (2000). Anti-PM-Scl100 (see Allmang et al., 1999b) was a gift of Reinout Raijmakers and Ger Pruijn. Anti-CPSF 160 (Santa Cruz), -CstF 64 (Santa Cruz) and -CstF 50 (ProteinTech Group) were used diluted at 1/500. Anti-SR domain peptide of hRNAse III (Biocarta) was used as described by Wu et al. (2000).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Alice Taylor for technical support and Sam Gunderson for the U1/G-less constructs. We are grateful to Walter Keller and Isabelle Kaufmann for the kind gift of anti-CPSF 73, -CPSF 30, -CFI 68 and -CFI 25 antibodies, and to Reinout Raijmakers and Ger Pruijn for the gift of anti-PM-Scl100 antibody. We also thank Andre Furger, Nick Proudfoot, Zbigniew Dominski and Nicolas Buisine for helpful suggestions and comments on the manuscript. P.U. was supported by MRC Co-operative Component grant No. G9900343 and S.M. by MRC Senior Fellowship No. G117/309.

References

- Ach R.A. and Weiner,A.M. (1987) The highly conserved U small nuclear RNA 3′-end formation signal is quite tolerant to mutation. Mol. Cell. Biol., 7, 2070–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allmang C., Kufel,J., Chanfreau,G., Mitchell,P., Petfalski,E. and Tollervey,D. (1999a) Functions of the exosome in rRNA, snoRNA and snRNA synthesis. EMBO J., 18, 5399–5410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allmang C., Petfalski,E., Podtelejnikov,A., Mann,M., Tollervey,D. and Mitchell,P. (1999b) The yeast exosome and human PM-Scl are related complexes of 3′ → 5′ exonucleases. Genes Dev., 13, 2148–2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienroth S., Keller,W. and Wahle,E. (1993) Assembly of a processive messenger RNA polyadenylation complex. EMBO J., 12, 585–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler J.S. (2002) The ying and yang of the exosome. Trends Cell Biol., 12, 90–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciliberto G., Dathan,N., Frank,R., Philipson,L. and Mattaj,I.W. (1986) Formation of the 3′ end on U snRNAs requires at least three sequence elements. EMBO J., 5, 2931–2937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad C. and Rauhut,R. (2002) Ribonuclease III: new sense from nuisance. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol., 34, 116–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuello P., Boyd,D.C., Dye,M.J., Proudfoot,N.J. and Murphy,S. (1999) Transcription of the human U2 snRNA genes continues beyond the 3′ box in vivo. EMBO J., 18, 2867–2877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries H., Rüegsegger,U., Hübner,W., Friedlein,A., Langen,H. and Keller,W. (2000) Human pre-mRNA cleavage factor IIm contains homologs of yeast proteins and bridges two other cleavage factors. EMBO J., 19, 5895–5904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dignam J.D., Lebovitz,R.M. and Roeder,R.G. (1983) Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res., 11, 1475–1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominski Z. and Marzluff,W.F. (1999) Formation of the 3′ end of histone mRNA. Gene, 239, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominski Z., Sumerel,J., Hanson,R.J. and Marzluff,W.F. (1995) The polyribosomal protein bound to the 3′ end of histone mRNA can function in histone pre-mRNA processing. RNA, 1, 915–923. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber H.P., Hagmann,M., Seipel,K., Georgiev,O., West,M.A., Litingtung,Y., Schaffner,W. and Corden,J.L. (1995) RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain required for enhancer-driven transcription. Nature, 374, 660–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gick O., Kramer,A., Keller,W. and Birnstiel,M.L. (1986) Generation of histone mRNA 3′ ends by endonucleolytic cleavage of the pre-mRNA in a snRNP-dependent in vitro reaction. EMBO J., 5, 1319–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson S.I., Knuth,M.K. and Burgess,R.R. (1990) The human U1 snRNA promoter correctly initiates transcription in vitro and is activated by PSE1. Genes Dev., 4, 2048–2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez N. (1985) Formation of the 3′ end of U1 snRNA is directed by a conserved sequence located downstream of the coding region. EMBO J. 4, 1827–1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez N. (2001) Small nuclear RNA genes: a model system to study fundamental mechanisms of transcription. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 26733–26736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez N. and Weiner,A.M. (1986) Formation of the 3′ end of U1 snRNA requires compatible snRNA promoter elements. Cell, 47, 249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez N. and Lucito,R. (1988) Elements required for transcription initiation of the human U2 snRNA gene coincide with elements required for snRNA 3′ end formation. Cell, 4, 3125–3134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose Y. and Manley,J.L. (1998) RNA polymerase II is an essential mRNA polyadenylation factor. Nature, 395, 93–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q., Jacobson,M.R. and Pederson,T. (1997) 3′ processing of human pre-U2 small nuclear RNA: a base-pairing interaction between the 3′ extension of the precursor and an internal region. Mol. Cell. Biol., 17, 7178–7185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel G.R. and Pederson,T. (1985) Transcription boundaries of U1 small nuclear RNA. Mol. Cell. Biol., 5, 2332–2340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamontagne B. and Elela,S.A. (2001) Purification and characterization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rnt1p nuclease. Methods Enzymol., 342, 159–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo S.M. and Marzluff,W.F. (1987) Synthesis of U1 RNA in isolated mouse cell nuclei: initiation and 3′-end formation. Mol. Cell. Biol., 7, 4290–4296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews D.H., Sabina,J., Zuker,M. and Turner,D.H. (1999) Expanded sequence dependence of thermodynamic parameters improves prediction of RNA secondary structure. J. Mol. Biol., 288, 911–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattaj I. and Zeller,R. (1983) Xenopus laevis U2 snRNA genes: tandemly repeated transcription units sharing 5′ and 3′ flanking homology with other RNA polymerase II transcribed genes. EMBO J., 2, 1883–1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken S. et al. (1997) 5′-Capping enzymes are targeted to pre-mRNA by binding to the phosphorylated carboxy-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev., 11, 3306–3318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medlin J.E., Uguen,P., Taylor,A., Bentley,D. and Murphy,S. (2003) The C-terminal domain of pol II and a DRB-sensitive kinase are required for 3′ processing of U2 snRNA. EMBO J., 22, 925–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore C.L. and Sharp,P.A. (1985) Accurate cleavage and polyadenylation of exogenous RNA substrate. Cell, 41, 845–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morlando M., Greco,P., Dichtl,B., Fatica,A., Keller,W. and Bozzoni,I. (2002) Functional analysis of yeast snoRNA and snRNA 3′-end formation mediated by uncoupling of cleavage and polyadenylation. Mol. Cell. Biol., 22, 1379–1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mougin A., Torteroto,F., Branlant,C., Jacobson,M.R., Huang,Q., and Pederson,T. (2002) A 3′-terminal minihelix in the precursor of human spliceosomal U2 small nuclear RNA. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 23137–23142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuman de Vegvar H.E., Lund,E. and Dahlberg,J.E. (1986) 3′ end formation of U1 snRNA precursors is coupled to transcription from snRNA promoters. Cell, 47, 259–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton J. and Wieben,E. (1987) U1 precursors: variant 3′ flanking sequences are transcribed in human cells. Cell Biol., 104, 175–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prelich G. (2002) RNA polymerase II carboxy-terminal domain kinases: emerging clues to their function. Eukaryot. Cell, 1, 153–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proudfoot N.J., Furger,A. and Dye,M.J. (2002) Integrating mRNA processing with transcription. Cell, 108, 501–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramamurthy L., Ingledue,T.C., Pilch,D.R., Kay,B.K. and Marzluff,W.F. (1996) Increasing the distance between the snRNA promoter and the 3′ box decreases the efficiency of snRNA 3′-end formation. Nucleic Acids Res., 24, 4525–4534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy R., Henning,D., Epstein,P. and Busch,H. (1981) Primary and secondary structure of U2 snRNA. Nucleic Acids Res., 11, 5645–5658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotondo G. and Frendewey,D. (1996) Purification and characterization of the Pac1 ribonuclease of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nucleic Acids Res., 24, 2377–2386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenberg D.R. and Cunningham,K.S. (1999) Characterization of mRNA endonucleases. Methods, 17, 60–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro D.J., Sharp,P.A., Wahli,W.W. and Keller,M.J. (1988) A high-efficiency HeLa cell nuclear transcription extract. DNA, 7, 47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahle E. and Rüegsegger,U. (1999) 3′-end processing of pre-mRNA in eukaryotes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev., 23, 277–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z. and Kiledjian,M. (2002) Functional link between the mammalian exosome and mRNA decapping. Cell, 14, 751–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Will C.L. and Lührmann,R. (2001) Spliceosomal UsnRNP biogenesis, structure and function. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 13, 290–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H., Xu,H., Miraglia,L.J. and Crooke,S.T. (2000) Human RNase III is a 160-kDa protein involved in preribosomal RNA processing. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 36957–36965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuo C.Y., Ares,M. and Weiner,A.M. (1985) Sequences required for 3′ end formation of human U2 small nuclear RNA. Cell, 42, 193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D., Lobo,F.D. and Ruppert,S.M. (1999) Pac1p, an RNase III homolog, is required for formation of the 3′ end of U2 snRNA in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. RNA, 5, 1083–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]