Abstract

Background. Choledochal cyst, a common surgical problem of childhood, can have a delayed presentation in adults. The clinical course in adults differs from that in children because of a higher incidence of associated hepatobiliary pathology. Methods. The clinical data of 57 adults with choledochal cyst managed in a general surgical unit between January 1988 and March 2003 were analysed. Results. The male:female ratio was 1:1.38 and the mean age was 34.5 years; 71.9% of the cysts belonged to Todani type I, 26.3% to type IV and 1.8% to type V. Abdominal pain and recurrent cholangitis were the commonest presentations followed by acute pancreatitis, palpable mass and bronchobiliary fistula. Anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal junction was demonstrated in 14% of the cases. In all, 37% of the patients had undergone either wrong or suboptimal surgical procedures prior to presentation. All patients underwent complete excision of the cyst and hepaticojejunostomy. Two patients required cholangiojejunostomy and three patients required resection of the involved segments of the liver in addition. There were three anastomotic leaks and two postoperative deaths. Two anastomotic leaks resolved spontaneously while the third required surgical intervention. Forty-eight patients were available for follow-up and have remained symptom-free over a mean period of 17.6 months. Conclusions. Choledochal cyst should be considered in all patients below 40 years of age presenting with biliary colic, pancreatitis or recurrent cholangitis with associated dilatation of bile duct. Complete excision of the cyst with restoration of biliary–enteric communication by hepaticojejunostomy form the basis of ideal treatment.

Keywords: Choledochal cyst, hepaticojejunostomy, cholangiojejunostomy, segmental liver resection

Introduction

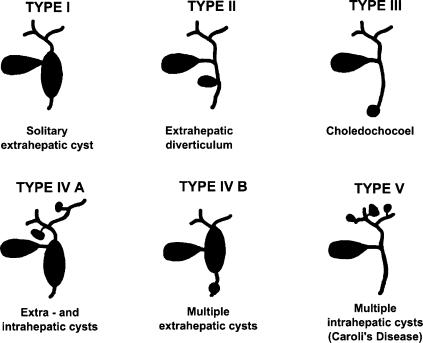

Choledochal cysts are congenital anomalies, which present as either isolated or combined dilatations of the extra- and intra-hepatic biliary tree. As the condition is not confined to the extrahepatic bile duct, the term ‘choledochal cyst’ is in fact a misnomer and ‘bile duct cyst’ or ‘biliary cyst’ is probably more appropriate. Nevertheless, due to the long-standing usage and familiarity, the term ‘choledochal cyst’ is generally accepted and its classification by Todani et al. into five types (Figure 1) addresses the anatomical variations of the condition adequately 1.

Figure 1. .

Todani's classification of choledochal cysts.

Choledochal cyst is usually a surgical problem of infancy and childhood. However, the diagnosis may be delayed until adulthood due to paucity of symptoms. Management of adult cysts is more demanding because of a higher incidence of associated biliary tract pathology. Irrespective of the age at presentation the basic principles of management remain the same – excision of the cyst and restoration of biliary–enteric communication. This report presents our experience in the management of adult choledochal cysts over a period of 15 years.

Materials and methods

Fifty-seven adults with choledochal cyst managed in a general surgical unit with special interest in hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery, between January 1988 and March 2003, were reviewed. The presenting complaints, investigations, previous treatment, associated pathology, operative details and postoperative course were analysed. Histopathological confirmation of the diagnosis was obtained in all cases. Follow-up information was obtained from outpatient records and through correspondence.

Results

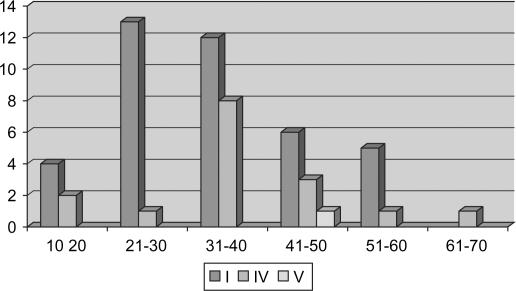

There were 24 males and 33 females with a male:female ratio of 1: 1.38. The mean age was 34.5 years, the range being 14–63 years. The incidence was highest in third and fourth decades followed by fifth and second decades (Table I and Figure 2).

Table I. Age and sex distribution of choledochal cysts in patients.

| Type | 1 |

IV a |

IV b |

V |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F |

| 10–20 | – | 4 | 2 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 21–30 | 2 | 11 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 31–40 | 8 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 1 | – | – |

| 41–50 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | – | – | 1 | – |

| 51–60 | 3 | 2 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 61–70 | – | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | |

Figure 2. .

Age and type distribution of choledochal cysts.

The cysts were categorized according to Todani's classification 1: 71.9% belonged to type I, 23.2% to type IV and 1.8% to type V cysts. Further subclassification of type IV cysts showed 13 patients with IVa and 2 patients with IVb cysts (Table I).

Most patients had long-standing symptoms, with a median duration of 24 months (Table II). In all, 70.2% of the patients presented with right hypochondrial pain, 22.8% with history of recurrent cholangitis, and 10.5% of them presented with acute pancreatitis. Clinical examination revealed hepatomegaly in 21.1% of the patients, while the choledochal cyst itself was palpable in only two patients. One patient presented with bronchobiliary fistula.

Table II. Adult choledochal cysts: clinical presentation.

| Presentation | Patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Abdominal pain | 40 (70.2%) |

| Recurrent cholangitis | 13 (22.8%) |

| Pancreatitis | 6 (10.5%) |

| Abdominal mass | 2 (3.5%) |

| Bronchobiliary fistula | 1 (1.8%) |

| Hepatomegaly | 12 (21.1%) |

Liver function test was normal in 10.5% of the patients, while serum bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase were elevated in 28% and 61.4%, respectively.

All patients underwent ultrasonography as the preliminary investigation. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) had been performed in 47 patients, 8 of whom revealed anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal junction (APBDJ). Of the eight APBDJs, six belonged to type a and 2 to type b, as per the classification suggested by the Japanese Committee for registration and study of the condition 2.

Eight patients had undergone magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatogram (MRCP) and computerized tomography (CT) had been performed on one patient.

Forty-one patients underwent 99m-technetium hepatic iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scan, which demonstrated stagnation of bile in a dilated bile duct even in the absence of intraductal calculi and mechanical obstruction to the flow of bile. Postoperative review included HIDA scan on all patients, which showed prompt and complete clearance of the isotope from the biliary tree.

Associated pathology (Table III)

Table III. Adult choledochal cysts: associated pathology.

| Pathology | Patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Cystolithiasis | 35 (61.4%) |

| Calculous cholecystitis | 20 (35.1%) |

| Hepaticolithiasis | 7 (12.3%) |

| Biliary stricture | 6 (10.5%) |

| Portal hypertension | 3 (5.3%) |

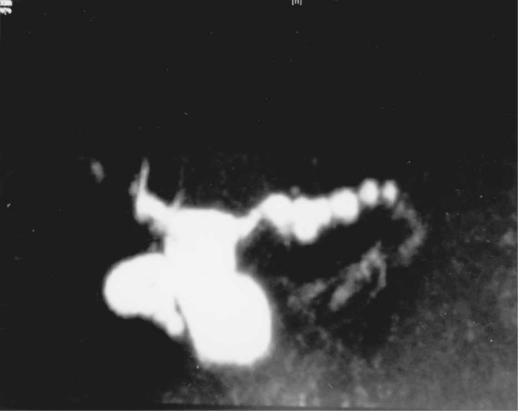

There was a 61.4% incidence of calculi within the choledochal cyst and in 57.1% of them the gall bladder also contained calculi. Of the seven patients who had hepatolithiasis, six belonged to type IVa cysts. The seventh patient had type I cyst with a stricture at the distal end of the right anterior sectoral duct. The dilated proximal portion of the duct contained calculi (Figure 3).

Figure 3. .

ERCP of a type I choledochal cyst, showing stricture at the distal end of the right anterior sectoral duct, sequestering segments V and VIII. The dilated duct contains multiple calculi.

Six patients with type I cyst had developed acute pancreatitis either before or at the time of presentation.

Six patients had associated biliary stricture, four of which were sequelae of surgical procedures on the bile duct. One was a post cholecystectomy stricture of Bismuth type III; a type I choledochal cyst was intact below the stricture. Two were anastomotic strictures at the cystoduodenostomy site of type I cysts. The fourth patient had a strictured hepaticojejunostomy, carried out elsewhere for Caroli's disease (type V); the disease in this patient had progressed further and resulted in a bronchobiliary fistula and atrophied right hemiliver. Two patients presented with de novo biliary strictures in the absence of previous surgery, one involving the hepatic ductal confluence and the other the right anterior sectoral duct just proximal to its termination, sequestering segments V and VIII of the liver (Figure 3).

Three patients had evidence of portal hypertension; one of them had secondary biliary cirrhosis with Child B category liver failure. All cases belonged to the postoperative biliary stricture group and had presented with recurrent cholangitis.

Earlier treatment (Table IV)

Table IV. Adult choledochal cysts: previous treatment.

| Previous treatment | n |

|---|---|

| Cholecystectomy + common bile duct exploration | 10 |

| Cholecystectomy | 4 |

| Choledochal cystoduodenostomy | 2 |

| Choledochal cystojejunostomy | 1 |

| Hepaticojejunostomy | 1 |

| Cholecystojejunostomy | 1 |

| Truncal vagotomy + gastrojejunostomy | 2 |

Fourteen patients had undergone cholecystectomy elsewhere and 10 of them had also undergone common bile duct exploration. All these patients had been erroneously diagnosed as calculous cholecystitis, with or without associated choledocholithiasis.

Four patients, despite a correct diagnosis of choledochal cyst, had undergone suboptimal surgical procedures – two cystoduodenostomies and one cystojejunostomy to the intact cyst and one hepaticojejunostomy following partial excision of the cyst.

One patient had undergone cholecystojejunostomy and two patients had undergone truncal vagotomy with gastrojejunostomy, for wrong diagnoses of advanced pancreatic malignancy and peptic ulcer disease, respectively.

Surgical procedures (Table V)

Table V. Adult choledochal cyst: surgical treatment.

| Type | n | Procedure |

|---|---|---|

| I | 40 | Excision choledochal cyst + Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy |

| 1 | Excision choledochal cyst + sectoral cholangiojejunostomy + hepaticojejunostomy | |

| IV A | 9 | Excision choledochal cyst + Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy + jejunal access loop |

| 1 | Excision by Lilly's technique + Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy + jejunal access loop | |

| 2 | Excision choledochal cyst + segmental resection of liver + Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy | |

| 1 | Excision choledochal cyst + right hemihepatectomy + Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy | |

| IVB | 2 | Excision choledochal cyst + Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy |

| V | 1 | Revision Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy and intrahepatic cholangiojejunostomy (Longmire's procedure) |

Complete surgical excision of the extrahepatic bile duct and restoration of biliary enteric communication by Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy was possible in all patients. In one patient with type IVa cyst, as the cyst wall was densely adherent to the portal vein, it was excised by Lilly's technique 3.

Three patients with acute pancreatitis underwent endoscopic sphincterotomy initially and excision of the cyst subsequently. Three patients with cholangitis had naso-biliary drainage and antibiotics for control of biliary sepsis initially and excision of the cyst later.

The case of type I cyst, with associated stricture of the distal end of the right anterior sectoral duct (Figure 3) had an additional cholangiojejunostomy performed between the dilated sectoral duct and the Roux Y limb.

In three patients with type IVa cyst, the intrahepatic component of the disease was localized and amenable to resection. Accordingly, two of them had a left lateral sectionectomy and the third had a right hemi-hepatectomy in addition to excision of the extrahepatic bile duct. In the remaining 10 cases of type IVa cysts, as the intra-hepatic component was generalized, a subcutaneously placed access loop using the Roux Y limb was fashioned.

The patient with type V choledochal cyst, strictured biliary–enteric anastomosis and atrophied right hemiliver underwent revision of the hepaticojejunostomy and a Longmire's type of intrahepatic cholangiojejunostomy 4.

Postoperative complications

Eight patients had minor wound infection, which healed spontaneously. There were three anastomotic leaks (5.3%), two of which settled with conservative management. The third patient required surgical intervention as there was an additional leak from the duodenal closure (following dismantling of previous choledochoduodenostomy) but had complete recovery.

There were two postoperative deaths. The first was a patient with type IVb cyst who had developed ERCP-induced gram-negative septicaemia preoperatively. Although he was operated upon after control of the sepsis, the septicaemia recurred postoperatively and proved fatal. The second was a 56-year-old male with type I cyst who died from unexplained cardiac arrhythmia.

Follow-up

Forty-eight patients were available for follow-up and have remained symptom-free after a mean follow-up period of 17.6 months. One patient who had undergone excision of a type I cyst developed intrahepatic calculi 4 years later. Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL) was attempted without success. Following this, a percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage was established and the tract was utilized later to fragment and extract the calculi.

Discussion

Bile duct cysts or biliary cysts commonly referred to as choledochal cysts are congenital cystic dilatations of the biliary tree, but in nearly 20% of the patients the diagnosis is delayed until adulthood 5. The presentation and therapeutic strategies for bile duct cysts in adults differ from those of younger patients because of an increased incidence of associated hepatobiliary pathology. Further, in a developing country like India, due to inadequacy of expertise and facilities in most areas, many patients tend to undergo either wrong or suboptimal surgical procedures, thus rendering surgical dissection of the upper abdominal compartment difficult. The fact that 37% of our patients (Table V) had already undergone various surgical procedures for their symptoms elsewhere highlights this as a major concern.

The aetiology of choledochal cysts remains speculative. The most widely accepted hypothesis is the presence of an anomalous pancreatico-biliary ductal confluence (APBDJ) proximal to the regulatory control of the sphincter mechanism within the duodenal wall 2,6. The condition predisposes to reflux of pancreatic juice into the bile duct, leading to activation of pancreatic enzymes and deconjugation of bile acids. The combination of activated pancreatic enzymes and deconjugated bile acids could induce chronic inflammatory changes in the bile duct and weaken portions of the biliary tree, predisposing the latter to abnormal dilatation. The observation that biliary cysts are more common in the extrahepatic biliary tree supports this hypothesis. However, the above anomaly could be demonstrated in only in eight (14%) of our patients. While this seems to tally with the experience of other authors 7,8, reports from Japan quote a much higher prevalence of 65% 9. A nationwide Japanese survey has classified APBDJ into three types based on the pattern of confluence between the terminal bile and pancreatic ducts – right angle type or type a, acute angle type or type b and complex type or type c 2. The geographical difference in the prevalence of APBDJ raises the possibility and relevance of other aetiological factors. Oligoganglionosis at the terminal portion of the bile duct causing functional obstruction and proximal dilatation has been implicated recently in the aetiology 10.

The classical triad of abdominal pain, mass and jaundice is seldom seen in adults 11. Abdominal pain and recurrent cholangitis are the most common presentations. The abdominal pain usually mimics that of calculous cholecystitis and many patients do have gallstones either in the cyst or in the gall bladder. This leads to a misdiagnosis of calculous cholecystitis and treatment by cholecystectomy and even common bile duct (CBD) exploration and in a few cases, biliary–enteric bypass. This is exemplified in our study by the 14 patients who had undergone cholecystectomy, 10 of whom had undergone CBD exploration elsewhere. In view of the relatively high incidence in our population, it is prudent to consider choledochal cysts in the differential diagnosis in patients under the age of 40 years who present with biliary colic, recurrent cholangitis and evidence of dilated CBD 7,12.

Ultrasonography provides adequate information about the intra- and extra-hepatic biliary tree and is an extremely useful initial investigation 13. ERCP defines the anatomy of the biliary tract accurately and reveals the presence of any associated intraductal pathology or an APBDJ 11,14. In the rare instance of a type III cyst, ERCP facilitates a therapeutic papillotomy simultaneously 15. MRCP, being a non-invasive procedure, is emerging as a favoured alternative to ERCP, but it has a lower accuracy in the detection of APBDJ and lacks the above therapeutic option in case of a type III cyst 16. Demonstration of stagnation of bile by HIDA scan in a dilated bile duct in the absence of intraductal calculi or biliary obstruction has been reported as a diagnostic sign 12.

Adult choledochal cysts are often associated with other biliary tract pathology, such as cystolithiasis, calculous cholecystitis, hepatolithiasis, intrahepatic abscesses, pancreatitis, biliary strictures, biliary cirrhosis with portal hypertension and cholangiocarcinoma 7,11,15,17.

The calculi in the cyst are of the type seen in biliary stasis 9,17. In type I and type IV cysts the calculi can be mistaken for choledocholithiasis in a dilated bile duct secondary to obstruction. The main distinguishing features are undilated proximal and intrahepatic biliary radicles in the case of type I cysts (Figures 1 and 3) and undilated intervening ducts in the case of type IV cysts (Figures 1 and 4).

Figure 4. .

Magnetic resonance cholangiogram of a type IVa choledochal cyst with multiple intrahepatic biliary dilatation and normal intervening ducts in segments II and III.

Biliary strictures associated with adult choledochal cysts are often related to earlier surgical procedures on the bile duct. However, rarely, strictures can occur de novo when an inflammatory or congenital aetiology can be considered 9.

Cirrhosis and portal hypertension are often associated with long-standing biliary obstruction and recurrent cholangitis. Although there was a low incidence of pancreatitis in our study (10.5%), a much higher incidence (23–70%) has been reported by other authors 6,11,20.

Cholangiocarcinoma of extrahepatic bile ducts associated with choledochal cyst 5 is known to arise within the cyst and the risk is about 20 times higher than that in the general population 18. A recent Japanese experience reports a 35% prevalence of bile duct carcinoma in patients with choledochal cyst 2 and the presence of APBDJ has been implicated as a factor in biliary carcinogenesis 2,19. The persistent or recurrent inflammation associated with APBDJ probably induces dysplastic changes in the mucosal lining of the bile duct or choledochal cyst, which in turn predisposes to carcinogenesis. Further, significant levels of carcinogens have been identified in the biliary contents in the presence of APBDJ 19. The absence of carcinoma as an associated pathology and the low incidence of APBDJ in our report and a rather high incidence of both in the Japanese experience seem to add credibility to the hypothesis.

The ideal treatment of choledochal cyst is its total excision. In types I and IV this involves complete excision of the bile duct from the confluence of the hepatic duct proximally up to the pancreaticobiliary junction distally 11,12,21,22,23 and restoration of biliary–enteric communication by a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. It has been noted that in type IV cysts there is often a membranous or septal stenosis of the hepatic ducts at their confluence, which can contribute to biliary stasis and formation of intrahepatic calculi 24. Therefore, inclusion of the proximal end of the common hepatic duct in the excision is vital for favourable long-term results following surgery 25,26,27.

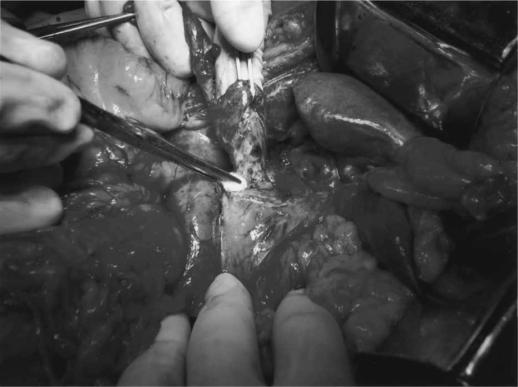

In adult choledochal cysts, the periductal or pericystic adhesions caused by chronic infection and recurrent inflammation create an unfavourable situation for dissection. However, our experience has shown that the inflammatory reaction is the least at the hilar region and periductal dissection to enter the correct plane and division of the duct are relatively easier at this site; thus we recommend it as the initial step of the operation 12. Gentle traction on the distal end of the cyst facilitates further dissection and ensures complete excision of the cyst (Figure 5) up to the pancreaticobiliary junction 12. Removal of the entire cyst wall is considered the most effective prophylaxis against malignancy and other associated biliary tract pathology 19.

Figure 5. .

Traction on the distal end of the choledochal cyst facilitates intra-pancreatic dissection of the terminal end of the cyst.

In situations where the intensity of fibrosis precludes safe periductal or pericystic dissection, it is advisable to follow Lilly's technique. Here, the most densely adherent portion of the cyst wall is retained on the hepatoduodenal ligament, removing only the less adherent portion 3. The mucosal lining of the retained cyst wall should be ablated by diathermy, as 57% of the cholangiocarcinomas in a choledochal cyst arises from the posterior wall of the cyst 28.

Cystenterostomy, which used to be performed in the past, is not considered a therapeutic option any more due to a high incidence of anastomotic stricture 5,22,23. The retained choledochal cyst continues to stagnate bile despite an adequate biliary–enteric stoma 12 and this predisposes to recurrent cholangitis and inflammatory fibrosis at the anastomotic site.

Localized intrahepatic disease is treated effectively by appropriate hepatic resection. However, when either a part or whole of the intrahepatic component remains, an access loop of the jejunum created with the Roux Y limb would provide an easy route for removal of intrahepatic calculi, biliary sludge or debris either endoscopically or radiologically. The access loop can be either placed subcutaneously or fashioned as duodenojejunal anastomosis 7,29,30. In two cases, in addition to hepaticojejunostomy, a cholangiojejunostomy between the dilated intrahepatic biliary radicles and the Roux Y limb was performed. These cases exemplify rare clinical situations where excision of functioning hepatic parenchyma would be either superfluous or contraindicated.

Conclusions

Choledochal cysts should be considered in the differential diagnosis in all patients with a history of biliary colic, recurrent cholangitis or pancreatitis with associated dilatation of bile duct, particularly if they are <40 years of age. Delay in the diagnosis increases the incidence of associated biliary pathology and suboptimal surgical therapy.

The ideal treatment for type I and IV cysts is complete excision of the extrahepatic bile duct and restoration of biliary–enteric communication by a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. Chronic inflammation involving the choledochal cyst and the adjacent tissues obliterates the periductal plane. Initial dissection and division of the bile duct at the hilar level facilitates further dissection of the cyst from adjacent structures up to its terminal end.

In type IVa cysts, if the disease is localized to a resectable portion of the liver, then the addition of segmentectomy, sectionectomy or hemihepatectomy is the ideal treatment. However, if the disease is generalized, a jejunal access loop may help to deal with recurrent complications such as stricture of biliary–enteric anastomosis and stone formation effectively by a non-surgical approach.

Rarely, cholangiojejunostomy between the dilated intrahepatic bile ducts and the afferent limb of the Roux loop of the jejunum would form an essential component of the surgical procedure for the disease.

References

- 1.Todani T, Watanabe Y, Narusue M, Tabuchi K, Okajima K. Congenital bile duct cysts: classification, operative procedures and review of 37 cases including cancer arising from choledochal cyst. Am J Surg. 1977;134:263–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(77)90359-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tashiro S, Imaizumi T, Ohkawa H, Okada A, Katoh T, Kawaharada Y, et al. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction: retrospective and nationwide survey in Japan. J Hepatobil Pancreat Surg. 2003;10:345–51. doi: 10.1007/s00534-002-0741-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lilly JR. The surgical treatment of choledochal cyst. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1979;149:36–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Longmire WP, Sandford MC. Intrahepatic cholangiojejunostomy with patial hepatectomy for biliary obstruction. Surgery. 1948;24:264–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flanigan PD. Biliary cysts. Ann Surg. 1975;182:635–43. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197511000-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okada A, Nakamura T, Higaki J, Okamura K, Kamata S, Oguchi Y. Congenital dilatation of bile duct in 100 instances and its relationship with anomalous junction. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1990;71:291–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hewitt PM, Krije EJ, Bornmann PC. Choledochal cysts in adults. Br J Surg. 1995;82:382–5. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800820333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choudhary A, Dhar P, Sachdev A. Choledochal cysts: differences in children and adults. Br J Surg. 1996;83:186–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujii H, Itakura J, Matsumoto Y. Clinical aspects of congenital cystic dilation of common bile duct in adults. J Hepatobil Pancreat Surg. 1996;3:423–30. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kusunoki M, Saitoh N, Yamamura T, Fujita S, Takahashi T, Utsonomiya J. Choledochal cysts. Oligoganglionosis in the narrow portion of the choledochus. Arch Surg. 1988;123:984–6. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1988.01400320070014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lipsett PA, Pitt HA, Colombani PM, Boitnott JK, Cameron JL. Choledochal cyst disease: a changing pattern of presentation. Ann Surg. 1994;220:644–52. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199411000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jesudason SRB, Govil S, Mathai V, Kuruvilla R, Muthusami JC. Choledochal cysts in adults. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1997;79:410–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akhan O, Demirkazik FB, Ozmen MN, Ayuriyek M. Choledochal cysts: ultrasonography findings and correlation with other imaging modalities. Abdom Imaging. 1994;19:243–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00203517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Komi N, Takehara H, Kunitomo K, Miyoshi Y, Yagi T. Does the type of anomalous arrangement of pancreaticobiliary ducts influence the surgery and prognosis of choledochal cyst? J Paediatr Surg. 1992;27:728–31. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(05)80102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin RF, Biber BP, Bosco JJ, Howell DA. Symptomatic choledochoceles in adults. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography recognition and management. Arch Surg. 1992;127:536–9. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1992.01420050056007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sugiyama M, Baba M, Atomi Y, Hanaoka H, Mizutani Y, Hachiya J. Diagnosis of anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction: value of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreaticography. Surgery. 1998;123:391–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uno K, Tsuchida Y, Kawasaki H, Ohmiya H, Honna T. Development of intrahepatic cholelithiasis long after primary excision of choledochal cyst. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;183:583–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Voyles CR, Smudja C, Shands C, Blumgart LH. Carcinoma in choledochal cysts – age related incidence. Arch Surg. 1983;118:986–8. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1983.01390080088022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Funabiki T, Matsubara T, Ochia LM, Watanabe Y, Seo T, Harada T, et al. Biliary carcinogenesis in pancreaticobiliary maljunction. J Hepatobil Pancreat Surg. 1997;4:405–11. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swisher SG, Cates JA, Hunt KK, Robert ME, Bennion RS, Thompson JE, et al. Pancreatitis associated with adult choledochal cysts. Pancreas. 1994;9:633–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ando H, Kaneko K, Ito T, et al. Complete excision of the intra-pancreatic portion of choledochal cysts. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;183:317–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagorney DM, McIlrath DC, Adson MA. Choledochal cysts in adults: clinical management. Surgery. 1984;96:656–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stain C, Gathrie CR, Yellin AE, Donavan AJ. Choledochal cyst in the adult. Ann Surg. 1995;222:128–33. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199508000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ando H, Ito T, Kaneko K, Seo T. Congenital stenosis of the intra-hepatic bile duct associated with choledochal cysts. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;185:426–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Todani T, Watanabe Y, Toki A, Urushihara N, Sato Y. Reoperation for congenital choledochal cysts. Ann Surg. 1988;207:142–7. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198802000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Todani T, Watanabe Y, Toki A, Ogura K, Wang ZQ. Coexisting biliary anomalies and anatomical variants in choledochal cysts. Br J Surg. 1998;85:760–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ando H, Kaneko K, Ito F, Seo T, Ito T. Operative treatment of congenital stenoses of the intrahepatic bile ducts in patients with choledochal cysts. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;173:491–4. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(97)00013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flanigan DP. Biliary carcinoma associated with biliary cysts. Cancer. 1977;40:880–3. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197708)40:2<880::aid-cncr2820400242>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McPherson SJ, Gibson RN, Collier NA, Speer TG, Sherson ND. Percutaneous transjejunal biliary intervention: a 10 year experience with access via Roux-en-Y Loops. Radiology. 1998;206:665–72. doi: 10.1148/radiology.206.3.9494484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monteiro Cunha JE, Herman P, Machando MC, Penteado S, Filho FM, Jukemura J, et al. A new biliary access technique for the long term endoscopic management of intrahepatic stones. J Hepatobil Pancreat Surg. 2002;9:261–4. doi: 10.1007/s005340200029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]