Abstract

Three-dimensional (3D) imaging is playing an increasingly important role in modern diagnostic radiology. The recent improvements in magnetic resonance (MR) hardware, scanning protocols and 3D volumetric reconstruction software have facilitated great expansion of the role of 3D imaging for use in hepatobiliary surgery. In this review, we address the various 3D reconstruction techniques used in MRI and demonstrate the value of 3D imaging in preoperative evaluation of hepatobiliary diseases.

Keywords: MRI, 3D imaging, hepatobiliary

Introduction

Before the implementation of volumetric imaging, hepatobiliary magnetic resonance (MR) images were routinely acquired using two-dimensional (2D) MR acquisition with relatively large slice thicknesses and inter-slice gaps. Thus, these 2D images could not be reconstructed into other planes without losing significant image resolution. In cases where information in other planes was required, the acquisitions had to be repeated in those specific planes. Volumetric imaging or 3D MRI helps to overcome this problem. The 3D data set is acquired in only one plane and the images in any other plane can be subsequently reconstructed using the same 3D data set. In addition, simple post processing of the 3D data set provides vascular information, if needed.

3D MRI has been shown to be helpful in the evaluation and diagnosis of parenchymal lesions and vascular anatomy using a single acquisition technique. 3D imaging allows the demonstration of fine anatomic detail, and the radiologist can manipulate images by removing or making them transparent of unwanted overlying structures, emphasizing areas of interest. These techniques allow radiologists and surgeons to better understand anatomic relationships. Thus, 3D MRI can be very useful for planning of surgical procedures such as preoperative evaluation of vascular and biliary ductal variations in living-related liver donors, assessment of vascular patency in patients undergoing surgical resection, preoperative liver and tumour volume measurements and virtual hepatectomy.

To accomplish the best 3D reconstruction for evaluation of hepatobiliary disease, the appropriate volumetric (3D) data have to be acquired. The dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging should be obtained fast enough to precisely capture the hepatic arterial and portal venous phases which are crucial for both lesion detection and characterization 1,2,3. The appropriate 3D post processing reconstruction including multiplanar reconstruction (MPR), maximum intensity projections (MIP), minimum intensity projections (MinIP), shaded surface display (SSD), volumetric rendering (VR) and volumetric segmentation, should be chosen to display structures of interest and pathology.

Volumetric imaging

In 1999, Rofsky et al. 4 introduced the 3D spoiled gradient echo sequence, which is known as volumetric interpolated breath hold sequence (VIBE). This MR pulse sequence allows us to acquire near isotropic 3D imaging of the entire hepatobiliary system within a breath hold. This volumetric 3D technique provides high spatial resolution images with short acquisition time (<25 seconds). Thus, this sequence can be performed repeatedly after the injection of gadolinium contrast to create the dynamic 3D images of the hepatobiliary system. Because the pixels are nearly isotropic (approximately 2–3 mm in all three dimensions), these axial 3D data sets can be reconstructed in any obliquity without loss in image resolution. When compared to the conventional 2D gradient echo sequences (2D GRE), the VIBE sequence allows for similar anatomic coverage with thinner sections. Therefore, the partial volume effect is minimized and the evaluation of finer details is more feasible when compared with 2D GRE 5,6. Table I details the differences between the images acquired with 2D GRE and 3D (VIBE) sequence. Representative 2D GRE and 3D VIBE images are shown in Figure 1.

Table I. Comparison of 2D GRE and 3D imaging technique (VIBE) in the same breath hold time frame and same anatomical coverage (hepatobiliary region).

| Parameters | MR sequences |

|

|---|---|---|

| 2D acquisition | 3D acquisition | |

| Pixel/voxel sizes | Anisotropic | Isotropic |

| Signal to noise ratio | Lower | Higher |

| Slice thickness | Thicker (8–10 mm) | Thinner (3 mm) |

| Gap between slices | Yes | No |

| Partial volume effect | ++ | – |

| Ghost artifacts | ++ | + |

| Truncation artifact* | + | ++ |

| Wrap around artifact* | – | + |

*Occur in slice encoding axis.

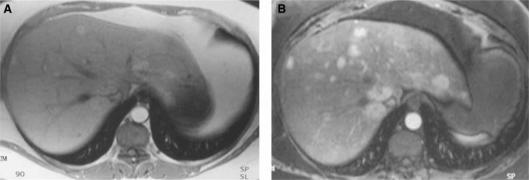

Figure 1. .

Post gadolinium chelate injection, 2D gradient echo image (A) versus 3D VIBE image (B) in a patient with multiple focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) lesions. Note that more lesions can be detected using the 3D technique. 3D VIBE image offers a greater degree of confidence in evaluation of small lesions (<1 cm)

Image post processing algorithms

With the improvement of 3D volumetric reconstruction software, the 3D data sets can easily be reformatted in coronal, sagittal, oblique or curved planes (curved MPR), which can help in lesion detection and localization. In addition, these modern 3D reconstruction softwares offer various other image post processing algorithms such as maximum intensity projection (MIP), sub-volume MIP, minimum intensity projection (MinIP), volume rendering and shaded surface display which can be especially helpful in understanding the anatomy of complex structures such as hepatobiliary vasculature and biliary ductal system. The accurate demonstration of bile duct, arterial and venous anatomy can be crucial in several clinical settings such as the evaluation of pre- and post-liver transplantation patients 7,8,9,10 and staging of hepatobiliary malignancy. 3D imaging offers the capability of precisely measuring the tumour or segmented liver volume, important in resection planning for certain large liver masses or for liver donor evaluation. Because of its enormous usefulness in clinical applications and its convenience, the integration of 3D reconstruction in clinical workflow is becoming a necessity in modern diagnostic radiology.

All the 3D images illustrated in this paper are commonly applied in hepatobiliary MRI and can readily be created with real-time visualization during routine image interpretation on a dedicated 3D Vitrea 2 workstation (Vital images, Plymouth, MN, USA).

Multi-planar reconstruction (MPR)

MPR is the reconstruction of images in arbitrary orientations such as orthogonal, oblique or curved plane. This method allows real-time viewers to slide through a given volume in any plane. Reformatted images frequently provide better demonstration and additional diagnostic information, particularly in the evaluation of complex anatomical structures or areas that are traditionally difficult to evaluate on axial images (Figures 2345).

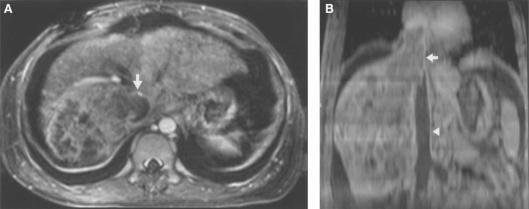

Figure 2. .

Gall bladder carcinoma. Axial image (A) and oblique coronal MPR (B) through the neck of gall bladder. The tumour arising from the gall bladder neck is clearly delineated in the oblique MPR (arrow). Also, the extent and cause of intrahepatic duct obstruction are better demonstrated (arrowheads).

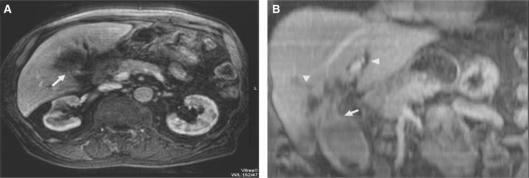

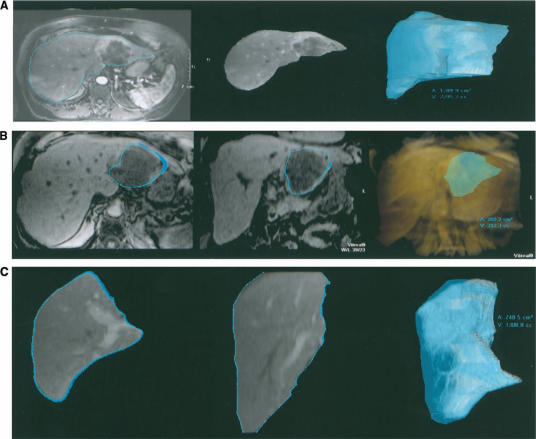

Figure 3. .

Hepatocellular carcinoma. Axial image (A) and coronal MPR (B) demonstrate enhancing tumour thrombus (arrow) and non-enhancing bland thrombus in inferior vena cava (IVC) (arrowhead). Note that the coronal MPR allows better demonstration of tumour extension and invasion of the IVC and differentiation between the tumour and bland thrombi.

Figure 4. .

Portal vein thrombosis. Oblique coronal MPR of a contrast-enhanced 3D VIBE acquisition during portal venous phase demonstrates non-visualization of the main portal vein and extensive portal venous collateralization consistent with cavernous transformation (arrow).

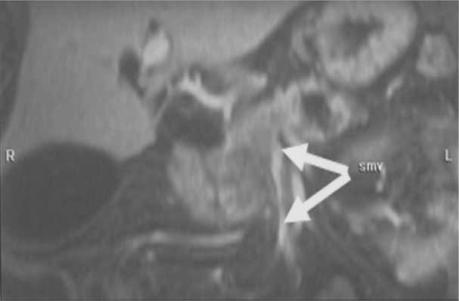

Figure 5. .

Diffuse HCC. Axial 3D VIBE image (A) shows non-opacification of portal vein (arrowhead). Oblique coronal MPR (B) clearly demonstrates the thrombus and its extent into right, left and main portal veins (arrows).

Maximum intensity projection (MIP) and sub-volumetric MIP

MIP is the projection of pixels with highest intensity onto an arbitrarily oriented plane. MIP images have an aspect similar to that of conventional angiograms and are commonly used for angiographic display such as evaluation of vascular anatomy. The drawback of MIP images is the lack of depth information so that the objects lying in the same projection plane of high intensity structures cannot be visualized 11. Eccentrically located stenoses may remain undetected, and superimposition of structures may simulate a stenosis 12. Multiple angle projections help to overcome this problem. The terms ‘sub-volumetric MIP’ or ‘thin MIP’ are used when only a small slab is reconstructed, instead of projecting the whole volume. The thickness of slab to be reconstructed can be adjusted. The thin MIP reconstruction technique can help to compensate for the loss of depth information in MIP images (Figures 6789).

Figure 6. .

MIP (A) and sub-volumetric MIP (B) reconstruction of MR angiography. These images demonstrate an aneurysm of the common hepatic artery (arrow) in a patient following liver transplant (arrow). Note that the aorta is not visualized on the thin MIP images as it is not included in the adjusted slab. Sub-volumetric MIP allows better visualization of the aneurysms.

Figure 7. .

Axial (A, B) and MIP reconstruction (C) images of coeliac axis and its branches demonstrate coeliac (arrow) and splenic (arrowhead) artery aneurysms.

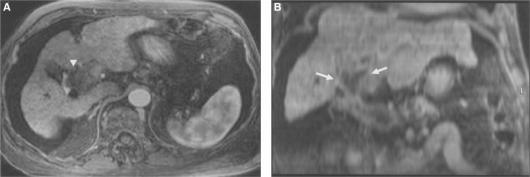

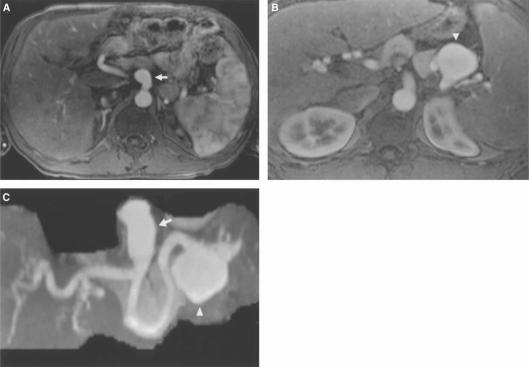

Figure 8. .

Pancreatic carcinoma. MIP reconstruction of arterial phase contrast-enhanced 3D VIBE acquisition shows tumour involving the head of the pancreas with encasement of superior mesenteric vein (arrow).

Figure 9. .

Budd-Chiari syndrome. Coronal (A) and axial (B) MIP reconstructions demonstrate absence of hepatic veins entering inferior vena cava (IVC) (arrow) and multiple collateral vessels (arrowheads).

Minimum intensity projection (MinIP)

In contrast to MIP, MinIP is the projection of pixels with lowest intensity onto an oriented plane. MinIP is most commonly used for evaluation of biliary ductal anatomy on post contrast images (Figure 10).

Figure 10. .

Infiltrative cholangiocarcinoma. MinIP reconstruction of a contrast-enhanced 3D VIBE acquisition clearly demonstrates thickened enhancing common bile duct wall against dark signal intensity of ductal lumen (arrow).

Shaded surface display (SSD) and volume rendering (VR)

SSD is the 3D display of surface from a series of contiguous slices using variable threshold settings. The 3D objects can be rotated and tilted in real time. The unwanted overlying structures can be easily eliminated using volume segmentation and confinement. As SSD allows 3D visualization, it enables the surgeon to obtain a clear 3D understanding of the patient's anatomy for improved surgical and treatment planning.

VR is another 3D visualization tool. In contrast to SSD, not only is the surface displayed but VR also allows the entire range of signal intensity within a volume data set to be illustrated. Objects with high signal intensity are opaque and objects with low signal intensity are transparent. Thus, the tissue differentiation is more feasible and the internal structures that would normally be hidden when using SSD can be demonstrated when using VR. The display parameters including window width, window level, opacity and brightness can be manipulated to obtain the optimal visualization of the areas of interest (Figures 11 and 12).

Figure 11. .

Shaded surface display reconstruction shows accessory right hepatic artery from the superior mesenteric artery (arrow).

Figure 12. .

Common origin of coeliac artery and superior mesenteric artery (SMA) is clearly demonstrated by lateral rotation of the 3D data set (arrow).

Liver volume and tumour volume measurement

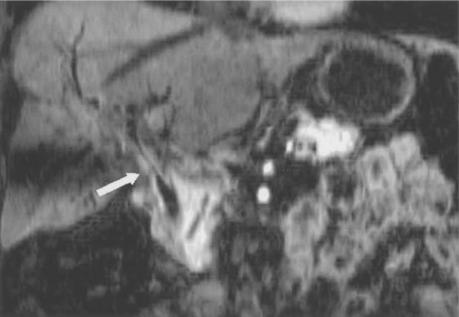

With the use of a modern 3D workstation, the measurement of liver, segmented liver, or tumour volume can be performed easily during routine clinical workflow. The average time needed to segment a portion of liver or determine tumour volume is usually less than 3 minutes. This function permits surgeons to anticipate the resected and residual liver volumes for a given surgical plane preoperatively (Figure 13).

Figure 13. .

Partial left hepatectomy was planned in a patient with cholangiocarcinoma involving left lobe of liver. Virtual hepatectomy was performed on a 3D workstation using segmentation tools. The liver volume (A), tumour volume (B) and the residual liver volume (C) can be estimated preoperatively.

Conclusion

Three-dimensional MRI plays an important role in hepatobiliary imaging. Most modern MR hardware has the capability to obtain 3D volumetric data, VIBE sequences, which improve lesion detection and characterization. With the volumetric data, various post processing image reconstructions could readily be done on the 3D workstation during the image interpretation at no additional cost. The reconstructions allow better demonstration of anatomic details, which help improve lesion localization and surgical planning. In our point of view, the volumetric data should be obtained, at least in a post gadolinium-enhanced scan, in every patient who undergoes abdominal MR examination. Particularly, in patients who are planned for surgery such as tumour assessment or pre-transplant evaluation, not only do the 3D reconstructions provide better tumour extent, tumour volume evaluation and an excellent anatomical guide map, but they also permit surgeons to anticipate the volume of residual normal tissue. While the precise details of image acquisition for 3D MR use in assessing hepatobiliary disorders is beyond the scope of the usual liver surgeon, knowledge of potential options for MR use is helpful to plan imaging analysis. Optimal patient assessment requires a close working relationship between the hepatobiliary surgeon and the MRI radiology team.

References

- 1.Hamm B, Mahfouz AE, Taupitz M, Mitchell DG, Nelson R, Halpern E, et al. Liver metastases: improved detection with dynamic gadolinium-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology. 1997;202:677–82. doi: 10.1148/radiology.202.3.9051015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamm B, Thoeni RF, Gould RG, Bernardino ME, Luning M, Saini S, et al. Focal liver lesions: characterization with nonenhanced and dynamic contrast material-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology. 1994;190:417–23. doi: 10.1148/radiology.190.2.8284392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peterson MS, Baron RL, Murakami T. Hepatic malignancies: usefulness of acquisition of multiple arterial and portal venous phase images at dynamic gadolinium-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology. 1996;201:337–45. doi: 10.1148/radiology.201.2.8888220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rofsky NM, Lee VS, Laub G, Pollack MA, Krinsky MA, Thomasson D, et al. Abdominal MR imaging with a volumetric interpolated breath-hold examination. Radiology. 1999;212:876–84. doi: 10.1148/radiology.212.3.r99se34876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell DG, Cohen MS. Saunders; Philadelphia: 2004. T1-weighted pulse sequences, Mitchell DG, Cohen MS. “MRI principles; pp. 237–47. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee VS, Lavelle MT, Krinsky GA, Rofsky NM. Volumetric MR imaging of the liver and applications: MR imaging of the liver. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2001;9:697–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lavelle MT, Lee VS, Rofsky NM, Krinsky GA, Weinreb JC. Dynamic contrast-enhanced three dimensional MR imaging of liver parenchyma: source images and angiographic reconstructions to define hepatic arterial anatomy. Radiology. 2001;218:389–94. doi: 10.1148/radiology.218.2.r01fe31389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim M, Mitchell DG, Ito K. Portosystemic collaterals of the upper abdomen: review of anatomy and demonstration on MR imaging. Abdom Imaging. 2000;25:462–70. doi: 10.1007/s002610000014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee VS, Morgan GR, Teperman LW, John D, Diflo T, Pandharipande PV, et al. MR imaging as the sole preoperative imaging modality for right hepatectomy: a prospective study of living adult-to-adult transplant donor candidates. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:1475–82. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.6.1761475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pandharipande PV, Lee VS, Morgan GR, Teperman LW, Krinsky GA, Rofsky NM, et al. Vascular and extravascular complications of liver transplantation: comprehensive evaluation with volumetric MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177:1101–7. doi: 10.2214/ajr.177.5.1771101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calhoun PS, Kuszyk BS, Heath DG, Carley JC, Fishman EK. Three-dimensional volume rendering of spiral CT data: theory and method. Radiographics. 1999;19:745–64. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.19.3.g99ma14745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hany TF, Schmidt M, Davis CP, Gohde SC, Debatin JF. Diagnostic impact of four postprocessing techniques in evaluating contrast-enhanced three-dimensional MR angiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:907–12. doi: 10.2214/ajr.170.4.9530032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]