Abstract

Background

Macrophage phagocytosis of apoptotic cells induces an anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype. Immune cell apoptosis is widespread in sepsis; however, it is unknown whether sepsis alters the capacity of macrophages to clear this expanded population. We hypothesize that sepsis will enhance splenic macrophage phagocytosis of apoptotic immune cells, potentially contributing to immunosuppression.

Methods

Sepsis was induced in C57BL/6J mice by cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). Apoptosis was induced in mouse thymocytes by dexamethasone incubation. At multiple time points following CLP/sham, splenic and peritoneal macrophages were isolated, plated on glass coverslips, co-incubated with apoptotic thymocytes, fixed, and the coverslips were then Giemsa stained. Splenic macrophages were also isolated 48 hours after CLP/sham, stained with the red fluorescent dye PKH26, co-incubated with green fluorescent dye CFSE-stained apoptotic thymocytes and then coverslips were fixed and counterstained with DAPI. The macrophage phagocytic index (PI) was calculated for both staining methods.

Results

The PI of CLP splenic macrophages was significantly higher than sham by 24 hours, and this difference was sustained through 48 hours.

Conclusions

Studies suggest that apoptotic cell clearance leads to an anti-inflammatory macrophage condition, which together with our findings in septic macrophages, may point at a process that contributes to septic immune suppression.

Keywords: Sepsis, mice, apoptosis, phagocytosis, macrophage

INTRODUCTION

Sepsis is a leading cause of death in the United States, with over 700,000 cases reported annually and a mortality rate of over 30%1. Sepsis has been defined as “the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) that occurs during infection”2. This definition, however, does not encompass fully the immunologic derangements that accompany the septic process. Sepsis will often times present with an early inflammatory response to an infection; however, as sepsis progresses, immunosuppression can become severe, leaving an already vulnerable patient ill-equipped to fight off the primary or new secondary infections3.

Sepsis has been demonstrated to induce widespread and profound immune cell apoptosis in multiple experimental animal models and observational human studies4,5. This increase in apoptosis is seen early following the infectious insult and across virtually every leukocyte population, with the exception of neutrophils, upon which sepsis has the opposite effect. Increased lymphocyte apoptosis has also been correlated with decreased survival in experimental animal studies, and this has also been confirmed in observational human studies4,6-8.

Immune cell apoptosis may contribute to the pathology of sepsis via multiple mechanisms. First, and most obvious, is the direct loss of competent immune cells in the setting of infection. Another potential mechanism, which is less obvious, implicates the body’s mechanisms for disposing of apoptotic material. This is a normal physiologic process that is necessary for the resolution of inflammation and tissue remodeling9-11. Once a cell becomes apoptotic, it must then be recognized as such and disposed of by phagocytes without the inflammatory cytokine release typically observed after contact with pathogens11. In fact, in vitro studies have demonstrated that exposure of macrophages to apoptotic cells causes the macrophages to acquire an anti-inflammatory phenotype12-15. We hypothesize that this greatly increased lymphocyte apoptosis may lead to a subsequent increase in macrophage clearance of these apoptotic cells. If the current in vitro evidence holds true in vivo, this could lead to an anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype shift on a large scale, thus potentially contributing to the immunosuppression seen in late sepsis.

It is unknown whether sepsis affects the capacity of macrophages to recognize and clear this vastly expanded population of apoptotic lymphocytes. We therefore set out here to test the hypothesis that sepsis will enhance the macrophage capacity to phagocytize apoptotic lymphocytes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male C57BL/6J mice, age 7-10 weeks, were used in all experiments. Mice were supplied by Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) and maintained under standard conditions. All procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Rhode Island Hospital Committee on Animal Use and Care.

Medium

RPMI 1640 medium, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and gentamycin were obtained from Gibco Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) and Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) were obtained from Hyclone (Logan, UT). RPMI 1640 medium plus 50ug/mL gentamycin plus 10% heat-inactivated FBS will be referred to as complete RPMI medium. DMEM plus 50ug/mL gentamycin plus 10% heat-inactivated FBS will be referred to as complete DMEM.

Cecal ligation and puncture

Sepsis was induced in mice using the cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) method as described by Baker et al16. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane, and their abdomens were shaved and prepped with betadine. Through a 1cm abdominal incision, the cecum was ligated with a 4-0 silk tie and punctured twice with a 22G needle. A small amount of stool was then extruded from the puncture sites, the cecum was repositioned in the abdomen, and the abdomen was closed in layers with 6-0 Ethilon suture (Ethicon, Inc. Somerville, NJ). Sham laparotomy without cecal ligation or puncture was performed in control mice.

Light Microscopy Protocol

Induction of thymocyte apoptosis

The thymus was harvested in as sterile fashion from healthy donor C57BL/6J mice, gently ground into a single cell suspension between frosted microscope slides, and filtered through a 70um filter. Thymocytes were then incubated in complete RPMI medium plus 1uM dexamethasone (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 5×106 cells/mL for 4 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2. Following incubation, thymocytes were washed twice with PBS and resuspended at 5×106 cells/mL in complete DMEM. Thymocytes to be used as non-apoptotic controls were isolated as described above and immediately suspended at 5×106 cells/mL in complete DMEM without dexamethasone incubation.

Flow cytometric assessment of thymocyte apoptosis

Unfixed thymocytes, with or without dexamethasone incubation, were stained with Annexin V-PE and 7-Amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD) (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Cells were acquired and analyzed using a BD FACSArray (Becton Dickinson) (Figures 1a and 1c).

Figure 1.

Typical flow cytograms are given for thymocytes that were stained with Annexin V and 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD) following dexamethasone incubation (a) or freshly isolated without dexamethasone incubation (c). The cumulative results of 3 separate experiments are presented as mean +/- SEM (b) (d). Total [Annexin V +], early [Annexin V+/ 7-AAD-], and late [Annexin V+/ 7-AAD+] apoptotic cell populations are presented.

Splenic macrophage isolation

At the designated time points (4, 12, 24, and 48 hours) following CLP/sham, mice were sacrificed by inhaled CO2 overdose. Spleens were harvested in a sterile fashion and gently ground to a single cell suspension between frosted microscope slides. Following lysis of erythrocytes with hypotonic saline, splenocytes were washed once with PBS and resuspended in complete DMEM. Splenocytes were counted and cell viability was assessed by Trypan Blue exclusion. Sterile 12mm round glass coverslips (Bellco Glass, Vineland, NJ) were positioned within 24-well tissue culture plates (Corning Inc. Corning, NY) and 107 cells in 1mL complete DMEM were added to each well. Cell solutions were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for two hours to allow for macrophage adherence, all non-adherent cells were removed with two washes of cold PBS, and 1mL fresh complete DMEM was added. Splenic macrophages were then incubated one additional hour during thymocyte preparation.

Peritoneal macrophage isolation

For comparison, peritoneal cells were harvested prior to opening the abdominal cavity by lavage with 4mL of cold PBS. Peritoneal cells were counted, assessed for viability with Trypan Blue, and 2×106 cells in 1mL complete DMEM were added to 24-well culture plates with inserted glass coverslips and incubated for adherence as above.

Co-incubation and staining

Medium was aspirated from each well of plated macrophages and 5×106 apoptotic or non-apoptotic thymocytes in 1mL of complete DMEM were added to each well. Plates were then incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 90 minutes after which the non-phagocytized cells were removed with two washes of cold PBS. Coverslips were then removed from the wells and rapidly dried with a protocol adapted from Licht et al17. Briefly, coverslips were positioned on “spinning pads” consisting of two Shandon filter cards (ThermoElectron Corp. Pittsburgh, PA) glued together with a 15×15mm hole cut from the top pad to accommodate the coverslips, then centrifuged at 25G for 10 minutes at 25°C. Coverslips were then fixed with 100% methanol for 10 minutes and immediately stained with a 1:1 mixture of May-Grunwald staining solution (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) and Gurr buffer (pH 6.8; VWR International, Poole, England) for 5 minutes followed by a 1:10 mixture of Giemsa staining solution (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and Gurr buffer for 15 minutes. Coverslips were then passed through two washes of Gurr buffer for 5 minutes each, air dried overnight, and mounted on microscope slides.

Phagocytic index

Macrophages were identified by cellular morphology under light microscopy and phagocytized thymocytes were identified as darkly stained nuclei completely within the cytoplasmic boundary of the macrophage (Figure 2a and 3a). Three hundred macrophages were counted per sample. The phagocytic index was calculated by multiplying the percentage of macrophages ingesting at least one thymocyte by the average number of ingested thymocytes per active macrophage.

Figure 2.

Splenic macrophages (arrow) that have phagocytized apoptotic thymocytes (arrowheads) as typically seen following May-Grunwald staining (a). Phagocytic index of splenic macrophages harvested at given time points after CLP/sham and co-incubated with apoptotic thymocytes (b). N = 4-8 mice/ group/ time point. * P<0.05, CLP vs. Sham, One-way ANOVA. # SEM=0.53. Phagocytic index of splenic macrophages harvested 48 hours after CLP/sham and co-incubated with either apoptotic thymocytes, non-apoptotic thymocytes, or no thymocytes (c). N = 4 mice per group.

Figure 3.

Peritoneal macrophages (arrow) that have phagocytized apoptotic thymocytes (arrowheads) as typically seen following May-Grunwald staining (a). Phagocytic index of peritoneal macrophages harvested at given time points after CLP/sham and co-incubated with apoptotic thymocytes (b). N = 4-8 mice/ group/ time point. * P<0.05, CLP vs. Sham, One-way ANOVA.

Fluorescence Microscopy Protocol

Thymocyte induction of apoptosis and staining

Thymocytes were isolated and apoptosis was induced as above. Following incubation with dexamethasone, thymocytes were washed once with PBS and stained with a 10uM solution of carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE; Molecular Probes, Eugene OR) in pre-warmed (37°C) PBS/0.1% bovine serum albumin (Fisher Biotech, Fair Lawn, NJ) per the manufacturer’s recommended alternate method to label cells in suspension. Following staining, thymocytes were suspended at 5×106 cells/mL of complete DMEM.

Splenic macrophage isolation and staining

Forty-eight hours after CLP or sham operation, splenocytes were isolated as above and stained with PKH26 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) per the manufacturer’s instructions. One milliliter of splenocytes at 107 cells/mL in complete DMEM were added to 24-well culture plates containing glass coverslips, and incubated for two hours for macrophage adherence as above. Non-adherent cells were removed by two washes with cold PBS, fresh complete DMEM was added, and macrophages were incubated one additional hour during thymocyte preparation.

Co-incubation

Medium was aspirated from each well of plated macrophages, 5×106 apoptotic CFSE-labeled thymocytes in 1mL of complete DMEM were added to each well and co-incubated for 90 minutes at 37°C and 5% CO2. Non-phagocytized cells were removed with two washes of cold PBS. Coverslips were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 45 minutes at room temperature, then mounted with mounting medium containing the blue nucleic acid dye DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Utilizing a Nikon Eclipse E400 (Nikon Inc. Mellville, NY) microscope, Mercury 100W light source (Chui Technical Corp. King’s Park, NY) and Polaroid DMC-3 digital camera (Polaroid, Cambridge, MA), macrophages were identified by nuclear morphology and phagocytized thymocytes were identified as DAPI-stained nuclei surrounded by green CFSE completely within the red cytoplasmic boundary of the PKH26-stained macrophage (Figure 4a). The phagocytic index was calculated as above. Confocal images were acquired with a Nikon PCM 2000 (Nikon Inc. Mellville, NY) using the Argon (488) and the green Helium-Neon (543) lasers. Images were collected with a 20x Plan Fluor lens and a scan zoom of 1x. Five micrometer sections were made through selected macrophages containing phagocytized thymocytes to assess the extent that the observations being made were of internalized/phagocytized not simply bound/adherent apoptotic cells.

Figure 4.

Typical morphology of PKH26-stained splenic macrophages isolated 48 hours after CLP/sham that have phagocytized CFSE-stained apoptotic thymocytes (a). Cumulative phagocytic index of splenic macrophages isolated 48 hours after CLP, stained with the red fluorescent viable cell dye PKH26, and co-incubated with CFSE-labeled apoptotic thymocytes (b). N = 4 mice per group. * P<0.05, CLP vs. Sham, Mann-Whitney Rank Sum Test. A typical PKH26-stained splenic macrophage that has phagocytized CFSE-stained apoptotic thymocytes (c). 5um consecutive horizontal sections starting at the slide surface (i) and moving through the macrophage cytoplasm (ii-viii). Images are from one representative of multiple examined macrophages.

Flow Cytometric Analysis of Splenocytes

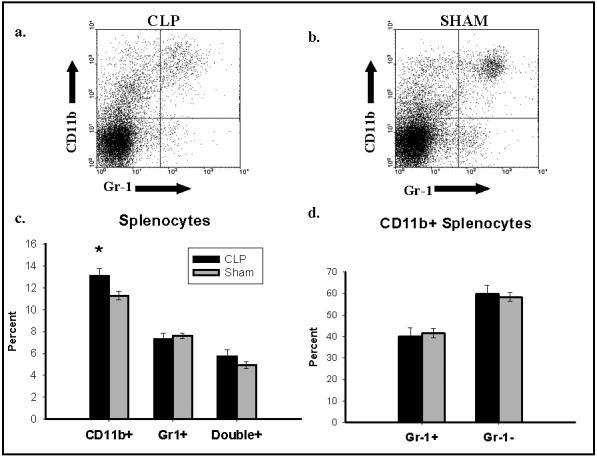

Splenocytes were isolated 48 hours after CLP or sham operation as above, incubated with 10ug/mL Fc block (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) for 15 minutes on ice followed by incubation with rat anti-mouse CD11b:RPE (AbD Serotec, Raleigh, NC) and rat anti-mouse Gr-1:APC-Cy7 (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Cells were immediately acquired and analyzed using a BD FACSArray.

Statistical Analysis

SigmaStat (Systat Software, Point Richmond, CA) software was used for statistical analysis. Results were expressed as mean values +/- SEM. Student’s T-test or Mann-Whitney Rank Sum Test was used to compare two variables at one time point. One-way ANOVA was used to compare two variables at multiple time points. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Thymocyte apoptosis

After four hours of incubation with 1uM dexamethasone, thymocytes consistently bound high levels of Annexin V, a ligand for phosphatidylserine and a marker of early apoptosis. Thymocytes also bound low levels of 7-AAD, a nucleic acid marker consistent with late apoptosis or early necrosis (Figure 1a and 1b). Furthermore, nearly all of the 7-AAD positive cells were also Annexin V positive, indicating that these cells are progressing through apoptosis to necrosis. This time of incubation and dexamethasone concentration were chosen as they were found in preliminary studies to produce the highest frequency of apoptotic (Annexin V+/ 7-AAD-) cells without inducing excessive necrotic and/or apoptotic-secondarily necrotic (Annexin V+/ 7-AAD+) cells. Thymocytes that were not incubated in dexamethasone bound low levels of both Annexin V and 7-AAD, indicating low levels of apoptosis in the control thymocytes (Figure 1c and 1d).

Light Microscopy

Splenic macrophages from CLP and sham mice had a similarly low phagocytic index at 4 and 12 hours; however, by 24 hours macrophages from CLP mice had a significantly higher phagocytic index (13.41+/-2.38 vs. 6.97+/-1.30), and this difference continued to increase by 48 hours (36.25+/-5.19 vs. 7.69+/-1.13) (Figure 2b). In contrast to the splenic macrophages isolated from mice 48 hours after CLP and co-incubated with apoptotic thymocytes, splenic macrophages from CLP mice that were co-incubated with non-apoptotic thymocytes had a nearly non-existent phagocytic index (Figure 2c). This indicates that the observed phagocytosis is specific for thymocytes undergoing cell death. As a comparison, peritoneal macrophages were also assessed at the same time points. Interestingly, macrophages from both CLP and sham mice had similarly high phagocytic indices at early time points (similar to macrophages from naïve mice), and this capacity trended downward over time in both groups until 24 hours. At the 48-hour time point, macrophages from CLP mice had a significantly higher phagocytic index than those from sham mice (26.74 +/- 5.38 vs. 7.09 +/- 1.97) (Figure 3b). This late increase in capacity to clear apoptotic cells paralleled that seen in the spleen.

Fluorescence Microscopy

Splenic macrophages isolated 48 hours after CLP had a significantly higher phagocytic index than macrophages from sham mice (20.8+/-4.42 vs. 1.8+/-0.37) (Figure 4b). This confirmed the difference seen at 48 hours using the Giemsa-based staining method. Using confocal microscopy, 5um sections of macrophages that had phagocytized thymocytes confirmed that the CFSE-labeled thymocytes were within the PKH26-labeled macrophage cytoplasm (Figure 4c).

Flow Cytometric Analysis of Splenic Macrophages

While representing a small fold overall increase, a significantly higher percentage of splenocytes isolated 48 hours after CLP expressed CD11b compared to sham (13.1 +/-0.64 vs. 11.3 +/- 0.41). Similar percentages of splenocytes from CLP and sham mice expressed Gr-1 (7.32 +/- 0.55 vs. 7.62 +/- 0.26) as well as CD11b and Gr-1 simultaneously (5.72 +/- 0.64 vs. 4.94 +/- 0.33) (Figure 5a-c). Gating upon CD11b+ cells, a similar percentage of cells in the CLP and sham groups expressed Gr-1 (40.04 +/- 4.00 vs. 41.60 +/- 2.13) (Figure 5d). CD11b+ / Gr-1+ cells have been identified as immature or “inflammatory” monocytes18,19. These data suggest that there is not an influx of monocytes into the spleen that would account for this increase in apoptotic cell clearance.

Figure 5.

Typical flow cytograms of splenic macrophages isolated from mice 48 hours after CLP (a) or sham (b) and stained with CD11b and Gr-1. Percentages of all splenocytes stained with either CD11b or Gr-1 alone, and for both CD11b as well as Gr-1 as delineated by flow cytometry are presented (c). *P<0.05, CLP vs. Sham, Student’s t-test. The percentage of CD11b positive splenocytes that are Gr-1 positive is presented (d). Cumulative results of 5 separate experiments are presented as mean +/- SEM.

DISCUSSION

Sepsis induces widespread and profound apoptosis across virtually every lymphocyte population4,5. This event has been shown to correlate with mortality, and inhibition at multiple points along the intrinsic or extrinsic apoptotic pathways has improved survival in animal studies4,6-8. The question of why this survival difference exists has yet to be elucidated. Are cells rescued from entering programmed cell death able to function as active components of the immune system, thus enabling the animal to resist overwhelming infection? Or, conversely, could a decreased load of apoptotic material contribute to this survival advantage by preventing apoptotic cell clearance and a subsequent anergic or even actively anti-inflammatory macrophage population? In this study, we have shown that splenic macrophages from septic mice exhibit an increasing capacity to engulf apoptotic thymocytes as sepsis progresses. It is interesting that both septic and sham splenic macrophages have a very low capacity to recognize and engulf these apoptotic immune cells early following the septic insult; however, later in the course of sepsis the capacity to take up these cells is enhanced. This would correlate well with the timeframe of immunosuppression known to be associated with this mouse model of polymicrobial sepsis20. In previous studies from our laboratory utilizing this model, plasma transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), classically implicated in immune suppression, was shown to be elevated in septic mice compared to sham at 24 hours, but not at earlier time points21. This is interesting in that in vitro data has shown an increase in macrophage release of TGF-β following exposure to apoptotic cells, which in turn also acts to decrease production of inflammatory cytokines (Interleukin-1β, Interleukin-8, GM-CSF, Tumor Necrosis Factor-α)12.

In regards to other anti-inflammatory cytokines observed in the plasma following CLP, our laboratory has also reported an increase in interleukin-10 (IL-10) at 24 hours in septic mice22,23. Others have reported an earlier increase in IL-10 after CLP, peaking at 16 hours and subsequently declining by 24 hours24. In a recent extensive evaluation of serum cytokine levels and their relation to early and late mortality in CLP, Osuchowski et al.25 evaluated plasma levels of multiple inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines from 6 to 72 hours after CLP. In this study, IL-10 was elevated as early as 6 hours after CLP in the subset of mice that would go on to early death (before 5 days), and gradually declined through 72 hours. The relationship between macrophage exposure to apoptotic cells and IL-10 levels is less clear than that of TGF-β. In studies by Fadok et al.12 and Lucas et al.14, the addition of apoptotic cells to LPS-stimulated macrophages actually decreased the release of IL-10. This would correlate with the declining levels of IL-10 reported by Osuchowski et al., and it also implies that any anti-inflammatory effect of apoptotic cell clearance is likely modulated initially through TGF-β release. As an interesting aside, it has recently been reported in a model of Burkitt’s lymphoma, that high levels of IL-10 are seen within these tumors, and IL-10 enhances the ability of macrophages to engulf apoptotic tumor cells, implicating IL-10 as a potential driver of this process26.

The most intriguing finding of our study is the dramatic increase in the phagocytic capacity of splenic macrophages as sepsis progresses; however, it must be noted that this is in contrast to that seen in peritoneal macrophages, which display a decline in capacity until 24 hours, then a late increase at 48 hours. This raises the question of whether what was observed in the spleen is a global phenomenon, or rather tissue specific. We attribute this difference to the idea that the peritoneal cavity is similar to a wound bed following CLP, with exposure to a large bacterial load followed by the subsequent influx of neutrophils and monocytes to the site of inflammation, which undoubtedly impacted the phagocytosis of apoptotic cells in our system. Furthermore, the staining techniques used to identify the peritoneal macrophages were based on cell morphology and were not adequate to discern between native peritoneal macrophages and infiltrating inflammatory macrophages; thus, there could be two different populations being observed, with varying ability to engulf apoptotic cells. The spleen is likely more indicative of what would be occurring systemically in response to a septic insult, as lymphocytes within the spleen have been observed to undergo high levels of apoptosis during sepsis4. Furthermore, macrophages from the spleen have been shown to increase the release of TGF-β, and decrease the release of the inflammatory mediators IL-6 and IL-12 in response to LPS treatment 24 hours after CLP as compared to sham, indicating that they are likely to be involved in immune suppression, at least on the local tissue level21,22. Similarly, splenocytes obtained from septic mice 24 hours after CLP have been shown to produce less IL-2 and interferon gamma (IFN-γ) and proliferate less in response to concavalin A stimulation as compared to sham, indicating that the function of the splenic T-cell population during sepsis may also be impaired21,27. The question of whether this is a global tissue phenomenon, however, still stands, and it would be beneficial to evaluate other tissue beds such as the liver, as well as serum monocytes, to resolve this issue. As mentioned, a weakness of this study is that while the staining methods are adequate to identify macrophages by cellular and nuclear morphology, they do not discern between macrophage phenotypes. Our flow cytometric data suggests, however, that there is not an influx of “inflammatory” monocytes (as defined by CD11b+Gr1+ expression) into the spleen during sepsis; therefore, it appears that there is more likely a resident splenic macrophage sub-population that upregulates the receptors necessary for clearance of apoptotic cells as sepsis progresses. In this respect, marginal zone macrophages have been implicated in the clearance of apoptotic cells, and would be a likely candidate28. However, discerning the phenotype of the macrophages responsible for this increased uptake of apoptotic material is a topic of further investigation.

Multiple receptors and ligands have been implicated in the interaction between apoptotic cells and phagocytes9-11. Some of these interactions have been demonstrated to be distinctly anti-inflammatory, such as those involving phosphatidylserine, while others, such as calreticulin/CD91, may induce inflammation; furthermore, it is likely a balance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory signals that influences the overall macrophage phenotype9. Our data suggest that splenic macrophages have an increasing capacity to take up apoptotic material as sepsis progresses, which is intriguing in that it corresponds with the immune suppression of late sepsis; however, which apoptotic cell receptors are responsible for this enhancement, and whether this enhanced uptake will lead to an anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype during sepsis requires further investigation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, Pinsky MR. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1303–1310. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, Dellinger RP, Fein AM, Knaus WA, Schein RM, Sibbald WJ. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Chest. 1992;101:1644–1655. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.6.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hotchkiss RS, Karl IE. The pathophysiology and treatment of sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:138–150. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wesche DE, Lomas-Neira JL, Perl M, Chung CS, Ayala A. Leukocyte apoptosis and its significance in sepsis and shock. J Leukocyte Biol. 2005;25:325–337. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0105017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oberholzer C, Oberholzer A, Clare-Salzler M, Moldawer LL. Apoptosis in sepsis: a new target for therapeutic exploration. FASEB J. 2001;15:879–892. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-058rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hotchkiss RS, Swanson PE, Freeman BD, Tinsley KW, Cobb JP, Matuschak GM, Buchman TG, Karl IE. Apoptotic cell death in patients with sepsis, shock and multiple organ dysfunction. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1230–1251. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199907000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Le Tulzo Y, Pangault C, Gacouin A, Guilloux V, Tribut O, Amiot L, Tattevin P, Thomas R, Fauchet R, Drénou B. Early circulating lymphocyte apoptosis in human septic shock is associated with poor outcome. Shock. 2002;18:487–494. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200212000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hotchkiss RS, Osmon SB, Chang KC, Wagner TH, Coopersmith CM, Karl IE. Accelerated lymphocyte death in sepsis occurs by both the death receptor and mitochondrial pathway. J Immunol. 2005;174:5110–5118. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.5110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henson PM, Hume DA. Apoptotic cell removal in development and tissue homeostasis. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:244–250. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gregory CD, Devitt A. The macrophage and the apoptotic cell: an innate immune interaction viewed simplistically? Immunology. 2004;113:1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01959.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fadok VA, Bratton DL, Henson PM. Phagocyte receptors for apoptotic cells: recognition, uptake and consequences. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:957–962. doi: 10.1172/JCI14122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fadok V, Bratton DL, Konowal A, Freed PW, Westcott JY, Henson PM. Macrophages that have ingested apoptotic cells in vitro inhibit proinflammatory cytokine production through autocrine/paracrine mechanisms involving TGF-beta, PGE2, and PAF. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:890–898. doi: 10.1172/JCI1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDonald PP, Fadok V, Bratton D, Henson PM. Transcriptional and translational regulation of inflammatory mediator production by endogenous TGF-β in macrophages that have ingested apoptotic cells. J Immunol. 1999;163:6164–6172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lucas M, Stuart LM, Savill J, Lacy-Hulbert A. Apoptotic cells and innate immune stimuli combine to regulate macrophage cytokine secretion. J Immunol. 2003;171:2610–2615. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lucas M, Stuart LM, Zhang A, Hodivala-Dilke K, Febbraio M, Silverstein R, Savill J, Lacy-Hulbert A. Requirements for apoptotic cell contact in regulation of macrophage responses. J Immunol. 2006;177:4047–4054. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.4047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baker CC, Chaudry IH, Gaines HO, Baue AE. Evaluation of factors affecting mortality rate after sepsis in murine cecal ligation and puncture model. Surgery. 1983;94:331–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Licht R, Jacobs CWM, Tax WJM, Berden JHM. An assay for the quantitative measurement of in vitro phagocytosis of early apoptotic thymocytes by murine resident peritoneal macrophages. J Immunol Methods. 1999;223:237–248. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon S, Taylor PR. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:953–964. doi: 10.1038/nri1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geissmann F, Jung S, Littman DR. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity. 2003;19:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ayala A, Chaudry IH. Immune dysfunction in murine polymicrobial sepsis: mediators, macrophages, lymphocytes and apoptosis. Shock. 1996;6:S27–S38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ayala A, Knotts JB, Ertel W, Perrin MM, Morrison MH, Chaudry IH. Role of interleukin 6 and transforming growth factor-beta in the induction of depressed splenocyte responses following sepsis. Arch Surg. 1993;128:89–95. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420130101015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song GY, Chung CS, Jarrar D, Chaudry IH, Ayala A. Evolution of an immune suppressive macrophage phenotype as a product of p38 MAPK activation in polymicrobial sepsis. Shock. 2001;15:42–48. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200115010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newton S, Ding Y, Chung CS, Chen Y, Lomas-Neira JL, Ayala A. Sepsis-induced changes in macrophage co-stimulatory molecule expression: CD86 as a regulator of anti-inflammatory IL-10 response. Surg Infect (Larchmt ) 2004;5:375–383. doi: 10.1089/sur.2004.5.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ebong S, Call D, Nemzek J, Bolgos G, Newcomb D, Remick D. Immunopathologic alterations in murine models of sepsis of increasing severity. Infection & Immunity. 1999;67:6603–6610. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.12.6603-6610.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Osuchowski MF, Welsh K, Siddiqui J, Remick D. Circulating cytokine/inhibitor profiles reshape the understanding of the SIRS/CARS continuum in sepsis and predict mortality. J Immunol. 2006;177:1967–1974. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogden CA, Pound JD, Batth BK, Owens IJ, Wood K, Gregory CD. Enhanced apoptotic cell clearance capacity and B Cell Survival Factor production by IL-10-activated macrophages: Implications for Burkitt’s lymphoma. J Immunol. 2005;174:3015–3023. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song GY, Chung CS, Chaudry IH, Ayala A. Immune suppression in polymicrobial sepsis: differential regulation of Th1 and Th2 responses by p38 MAPK. J Surg Res. 2000;91:141–146. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2000.5928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kraal G, Mebius R. New insights into the cell biology of the marginal zone of the spleen. International Review of Cytology. 2006;250:175–215. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(06)50005-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]