Increasingly, it is recognized that the many factors and determinants underlying healthy, successful societies require the involvement of a variety of sectors from within those societies. As one of these sectors, public health is inextricably linked to human development, through activities such as improvements in sanitation and access to clean water, advances in immunization and microbiology, advocacy for appropriate housing and nutrition, health promotion efforts and social reforms. As such, public health measures have played important roles in the successes of various societies and their economies. In the broader agenda to improve health and well-being and to reduce inequalities, public health has played, and can continue to play, many roles.

There is little doubt that, despite recent advances in public health, some countries are being left behind. As just one example, in Zambia in 2005 a child could, for a variety of reasons, expect to live about 38 years,1 little better than what might have been expected in the Bronze Age. For another example, we can look to the impact of malaria in Africa. Causing severe illness in 500 million people each year, this disease accounts for an estimated average loss of 1.3% in annual economic growth, which, compounded over the years, can account for significant deficiencies in gross domestic product.2,3 In this, we must remember that health is not merely a consumer of resources; it is also a driver of economies. The question thus arises as to how we can effectively work with developing countries and disadvantaged communities around the world to improve health and development.

The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) was created in 2004 to provide national guidance, leadership and coordination in public health. While the nature of the agency means that addressing public health here in Canada is a priority, it is also clear that the health of the Canadian public is very much connected to the health, well-being and success of communities outside our borders. The outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome reinforced our understanding that a public health crisis is just a plane ride away and that taking an isolated approach to public health ignores the interconnectedness of the modern world.

Public health is more than a set of programs and services; it is a way of understanding and addressing the causes of ill health or, as Michael Marmot, chair of the World Health Organization (WHO) Commission on the Social Determinants of Health, would say, “the causes of the causes.”4 It is a whole-society approach to addressing the determinants of health, creating supportive environments and working to ensure that every person has the opportunity to be healthy and to prosper. Increasing the knowledge base for the factors that underlie health inequalities within countries, as well as between developing and developed countries, is a vital first step. The Commission on the Social Determinants of Health, supported by PHAC and other federal partners through a Canadian reference group5 and through a series of global knowledge networks,6 is helping to develop that knowledge base by generating and sharing information and by facilitating the participation of low-and middle-income countries in forums that seek to reduce these inequalities.

The following are just a few examples of the work that PHAC is doing and will continue to do in the coming years.

PHAC recently sponsored representatives from low-and middle-income countries to participate in a dialogue on approaches for working across sectors to improve health equity. This dialogue will inform recommendations to be made to the WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health for inclusion in its final report. Canada also sponsored representatives from several developing countries to attend a symposium in Adelaide, Australia, thus supporting an international exchange between indigenous peoples on the social determinants related to the health of these groups. The Commission on the Social Determinants of Health is due to release its final report, with official recommendations, in May 2008.7 This report will guide and inform public health activities around the world.

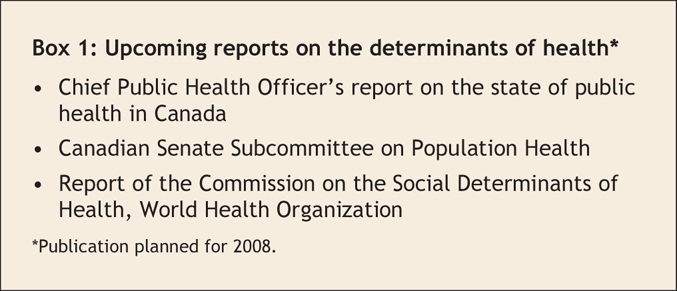

Canada is also contributing to increasing knowledge through a pair of upcoming reports (Box 1). In 2008, I will release the first Chief Public Health Officer's report on the state of public health in Canada, focusing on the country's health inequalities. The second report, now being developed by the Canadian Senate Subcommittee on Population Health, will examine the impact of social determinants on Canadians' health. Although these reports will focus on public health in Canada, some knowledge will be transferable, and both will reaffirm this country's commitment to knowledge generation and learning.

Box 1.

In addition to partnering with organizations and international networks, PHAC also works directly with many developing nations to help mitigate the impacts of public health events. For instance, in January 2007, in collaboration with several other countries and international organizations, the agency assisted the Kenyan ministry of health in containing an outbreak of Rift Valley fever, and in spring 2005, agency scientists joined a WHO mission in Angola to provide laboratory support during a Marburg virus outbreak.

The PHAC is also devoting substantial efforts to reducing the global burden of chronic disease. Canada has been a strong supporter of the Global Strategy on Non-Communicable Diseases and related resolutions in this area, including the Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health (www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/en/), the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (www.who.int/gb/fctc/) and others. At the 2003 World Health Assembly, Canada recommended securing commitments from each member state to develop a national plan of action consistent with the principles and recommendations of the Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health.

In terms of research, ongoing work at PHAC's National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg brings us closer every day to vaccines against organisms such as the Ebola and Marburg viruses and against the broader threat of pandemic influenza. Scientists at the Winnipeg laboratory have also been working closely with laboratory experts in Vietnam to study influenza viruses and prevention measures. The Canadian HIV Vaccine Initiative, supported by funding from PHAC and other federal departments and agencies, and in partnership with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, is contributing to worldwide efforts to accelerate the development of globally accessible HIV vaccines. The PHAC has also contributed resources and expertise to the recently established International Infectious Disease Centre in Kenya, a state-of-the-art research centre, accessible to researchers from all contributing countries, that is able to respond quickly to outbreaks of infectious disease. These kinds of partnerships and information-sharing endeavours offer immense benefits to populations in developing nations that are in need of these shared resources.

At PHAC, we recognize that globalization presents countries and communities with both opportunities and challenges in public health. How we build and maintain our public health systems as part of larger reforms will contribute to our success as societies and to the development and support of those currently living in poverty. In supporting international organizations and networks to strengthen public health infrastructures, in contributing to the development and sharing of public health knowledge and research, and in working directly with communities to mitigate the impacts of public health emergencies abroad, PHAC will continue to work toward realizing its vision of not only healthier Canadians, but also healthier communities in a healthier world.

Key points of the article

To improve public health at home and abroad, the Public Health Agency of Canada engages in the following activities:

• Works with its domestic and international partners to study and address the determinants of health

• Facilitates dialogue and knowledge-sharing among partners

• Strengthens domestic and international public health infrastructure

• Engages in new research

• Helps to mitigate the impacts of outbreaks and other public health emergencies abroad

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. David Butler-Jones, Public Health Agency of Canada, 130 Colonnade Rd., Ottawa ON K1A 0K9; fax 613 941-3605; cpho-aspc@phac-aspc.gc.ca

REFERENCES

- 1.World development indicators (WDI) 2007 database. Geneva: World Bank; 2007.

- 2.Malaria [fact sheet no 94]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. Available: www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs094/en/print.html (accessed 2007 Sept 24).

- 3.Gallop JL, Sachs JD. Theeconomicburdenofmalaria[Working Paper no 52]. Cambridge(MA):CenterforInternationalDevelopmentatHarvardUniversity; 2000.

- 4.Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet 2005;365:1099-104. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Canadian Reference Group on Social Determinants of Health. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2006. Available: www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/media/nr-rp/2006/2006_06bk3_e.html (accessed 2007 Sept 24).

- 6.Canada's response to WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2007. Available: www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/sdh-dss/kn-rs_e.html (accessed 2007 Sept 24).

- 7.Department of equity, poverty and social determinants of health. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available: www.who.int/social_determinants/equity/en/index.html (accessed 2007 Sept 24).