Abstract

We demonstrate nanoscale resolution in far-field fluorescence microscopy using reversible photoswitching and localization of individual fluorophores at comparatively fast recording speeds and from the interior of intact cells. These advancements have become possible by asynchronously recording the photon bursts of individual molecular switching cycles. We present images from the microtubular network of an intact mammalian cell with a resolution of 40 nm.

INTRODUCTION

Far-field fluorescence microscopy is of key relevance to the life sciences because it enables three-dimensional imaging of cellular constituents with unrivaled specificity. However, for many years its resolution was limited by diffraction to about half the wavelength of light, λ/2 > 200 nm. Matters began to change when it became clear that the spectral properties of the fluorescence markers, in particular their molecular states, may not only be used to generate signal, but also to dramatically increase the spatial resolution (1). For example, stimulated emission depletion microscopy (2) overcomes the diffraction limit by effectively confining the fluorescent state of the marker to a well-defined region ≪λ/2. To this end, a beam of light is used to effectively keep the marker in the ground state everywhere except at a point or line where this beam is zero (3). This concept has been extended to using any marker which can be optically kept or transferred to a dark state, in particular to photoswitchable organic fluorophores and photoactivatable proteins (3). In all cases, the subdiffraction image is assembled sequentially in time, by translating the location of the intensity zero through the sample. When assembling an image in this way the (switchable) fluorophores must undergo several off-on-off cycles.

Multiple switching is elegantly avoided if the molecules are recorded individually rather than in an ensemble. This is possible by illuminating deactivated but switchable dyes with so little activation light that only a few isolated molecules are transferred to the bright state at a time. Upon excitation, the on-state molecules can fire many fluorescent photons in a row, while their neighboring molecules remain entirely dark. Since a single molecule in the on-state already represents the smallest possible spot no additional optical confinement is needed to reduce the fluorescent spot any further. However, unlike in the ensemble case, where the position of the bright marker molecules is given by the position of the zero, the exact position of the switched-on or activated molecule is unknown. By imaging the burst of emitted fluorescence on a pixilated detector such as a camera and exploiting the a priori knowledge that the emission stems from the same point, the position of the molecule can be determined with a precision much higher than the full width at half-maximum of the point-spread function (PSF) of the imaging lens (4–9). In this way each molecule can be precisely mapped so that an image can be assembled. After recording, the molecule has to be switched off again, meaning that the molecule underwent just a single switching cycle. This single molecule recording method was termed photoactivated localization microscopy (PALM) (10), fluorescence photoactivation localization microscopy (FPALM) (11), or stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM) (12). Its resolution is determined by the localization precision which is given by  with n being the number of photons detected per activated molecule. In fact, the resolution of the final image can be somewhat tuned by including only those events where n is above a certain threshold.

with n being the number of photons detected per activated molecule. In fact, the resolution of the final image can be somewhat tuned by including only those events where n is above a certain threshold.

Implemented in a wide-field setup, this novel nanoscopy form is very powerful (13). Nonetheless it has so far entailed a number of limitations. Working with low densities of fluorescent molecules (14), it is so sensitive to diffuse background that a total internal reflection fluorescence microscope has been preferred for recording. This measure limited the method to two-dimensional samples, specifically to sectioned slices thinner than 100 nm (10). Furthermore, extremely long image acquisition times of 2–12 h were reported to form a meaningful image of biological specimens (10). We now overcome these limitations by changing both the fluorescent protein and the mode with which we record the biological sample. In particular, employing the fast reversibly photoswitching fluorescent protein (RSFP) rsFastLime (15), a variant (V157G) of the reversibly switchable fluorescent protein Dronpa (16), in combination with fast and asynchronous recording (17), accelerates image acquisition ∼100-fold, cutting down the recording time to 2–2.5 min. Furthermore, our strategy reduces background, thus allowing us to image from within the interior of intact (nonsliced) cells. Because we record nontriggered, spontaneous off-on-off cycles without synchronization of the detector, we refer to this method as PALM with independently running acquisition (PALMIRA).

METHODS

PALMIRA setup

The arrangement of our wide-field imaging setup is illustrated in Fig. 1. The beam of an Argon Ion Laser (Innova 300, Coherent, Santa Clara, CA) running at a wavelength of 488 nm is intensity-controlled by an acousto-optical tunable filter (AOTF, AA Opto Electronic, New York, NY) and expanded by a telescope (T). Background is removed by a cleanup filter (Z488, 10, Chroma Technology, Rockingham, VT) and the beam is converted from linear to circular polarization by a quarter wave plate (L4) and subsequently coupled into a regular commercial wide-field microscope (DMIRE 2, Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). We assure uniform epiillumination of a 10-μm field-of-view by under-illuminating the back aperture of the objective lens (HCX APO 100×/1.30 Oil U-V-I 0.17/D, Leica Microsystems). The fluorescent light is collected by the same objective lens, separated from the laser light by a dichroic filter (495DCXR, Chroma Technology) and imaged onto an electron multiplying charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (IXON-Plus DU-860, Andor Technology, Belfast, Northern Ireland). Stray laser light and background outside the dye's emission spectrum is removed by a notch filter (NF, DNPF488-25, LOT-Oriel, Darmstadt, Germany) and a bandpass filter (BP, HC525/50, Semrock, Rochester, NY).

FIGURE 1.

PALMIRA setup. The excitation beam is intensity controlled by an acousto-optical tunable filter (AOTF) and expanded by a telescope (T). Background is removed by a cleanup filter (CF) and the beam is converted from linear to circular polarization by a quarter wave plate (L4) and coupled into a regular commercial wide-field microscope. The fluorescent light is separated from the laser light by a dichroic filter (DF) and imaged onto an electron multiplying (EM) CCD camera. Stray laser light and background is removed by a notch (NF) and a bandpass filter (BP).

Position determination

The planar positions of the fluorophores in a sparsely activated sample are determined by the use of Hogbom's classical CLEAN algorithm (18) in conjunction with a mask-fitting algorithm of the Airy spot. The CLEAN algorithm provides data segmentation whereas the localization serves to find the precise position of the emitting molecule. This interplay between the two algorithms is illustrated in Fig. 2. The subtraction of the PSF entailed by the CLEAN algorithm resulted in a more adequate treatment of slightly overlapping Airy peaks as was the case for simple connection-based segmentation procedures.

FIGURE 2.

The combined CLEAN/mask-fitting algorithm used to identify and localize single emitters in individual camera frames. Each image is initially smoothed by a Gaussian filter that is much narrower than the PSF (full width at half-maximum of 70 nm); the resulting noise reduction is sufficient to provide notably better segmentation without compromising the localization precision. Subsequently, the pixel with the highest photon count is identified and used as a starting point for the mask-fitting iteration described in the text. If this iteration converges, the retrieved two-dimensional position of the marker is tabulated together with the number of photons constituting the event. A theoretical PSF is then subtracted from the image, scaled in such a way that the amplitude at the dye's position becomes zero above the median background. The algorithm then reiterates, identifying the pixel with the highest photon count. The escape point is reached when this photon count is below a certain threshold value, which is chosen well above background level to avoid artifacts.

The localization itself is equivalent to the Gaussian mask-fitting algorithm described in Thompson et al. (19) and runs in the form of a fixed point iteration: At the beginning, the starting point  is set to the center of the pixel with the highest photon count. Then, in each iteration, the center of mass

is set to the center of the pixel with the highest photon count. Then, in each iteration, the center of mass  of the data multiplied by a PSF centered at the point

of the data multiplied by a PSF centered at the point  is determined. Usually, the algorithm converges after a few iterations. If after 50 iterations the path of

is determined. Usually, the algorithm converges after a few iterations. If after 50 iterations the path of  is longer than the size of an Airy disk, this is considered as a divergence, and the corresponding molecule is discarded.

is longer than the size of an Airy disk, this is considered as a divergence, and the corresponding molecule is discarded.

Drift and vibration compensation

During our typical image acquisition times of 2–2.5 min, we observed a sample drift of some tens of nanometers. Therefore, we added fluorescent microspheres to the samples. By tracking these bright particles (typically more than 2000 photons/frame), we corrected for the errors in the determined positions of individual fluorophores during the post-processing analysis.

Conventional image retrieval

In the case of negligible readout noise, the epifluorescent counterpart image to the superresolved PALMIRA image is given by the sum of the individual frames. The conventional images shown in Figs. 4 A and 5 A were therefore determined by summing up all recorded frames and setting the lowest pixel count to zero.

FIGURE 4.

Imaging E. coli. Conventional (A) and PALMIRA (B) image of a 200-nm-thick cryosection of cytoplasmic membrane labeled E. coli. The image was recorded in 140 s.

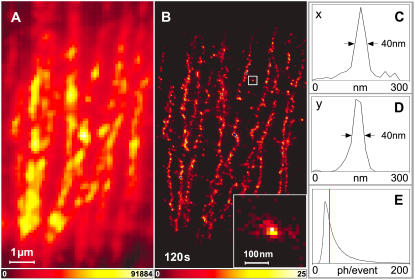

FIGURE 5.

Imaging stained α-tubulin inside intact PtK2 cells. Conventional (A) and PALMIRA (B) image. The image was recorded in 120 s. The averaged line profiles in x (C) and y (D) direction of a single rsFastLime molecule or agglomeration of molecules (inset in B) prove a focal plane resolution of 40 nm. The distribution of detected photons per single molecule event is depicted in panel E. For large photon counts (>30), it is well approximated by a geometrical distribution with an expectation value of ∼21. Only events with 35 photons or more (red vertical line) were chosen for the data representation.

Protein production and purification

The RSFP rsFastLime was expressed in the Escherichia coli strain HMS 174 (DE3) and purified by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography and subsequent size-exclusion chromatography according to standard procedures (15). The purified proteins were concentrated to ≈33 mg/ml and taken up in 100 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5.

Single molecule spectroscopy

To acquire time traces of isolated molecules as shown in Fig. 3, coverslips were rinsed with deionized water for 5 min and cleaned in a low pressure plasma system (Femto-RF, Diener Electronic, Nagold, Germany). A phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-based solution with 1.27 nM rsFastLime, 0.1% (w/v) Polyvinyl alcohol (88 mol % hydrolyzed, Polysciences Europe, Eppelheim, Germany) and 0.32% (w/v) L-ascorbic acid (A.C.S. reagent, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was prepared. The pH was adjusted to 7.4. A 40-μl aliquot of the solution was pipetted onto the coverslip, which was then spin-coated for 20 s at 3000 rpm (Spin-Coater KW-4A, Chemat Technology, Northridge, CA). The overall image acquisition time was 40 s (500 frames/s) and the light intensity (488 nm) was 5.0 kW/cm2.

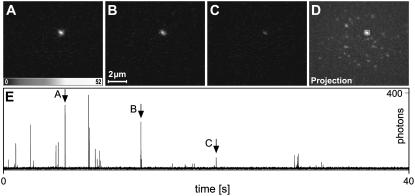

FIGURE 3.

Imaging single rsFastLime molecules. Three typical recordings of a sparse rsFastLime sample (A–C) and the maximum projection from the whole series of 20,000 frames (D). The object marked in panel D is most likely a single molecule as the rsFastLime concentration was only 1.27 nM and our position retrieval algorithm did not show any indication that the object represents more than one molecule. In panel E, the time trace, integrated over the 4×4 pixels marked in panel D, is shown. The RSFP is switched on and off over 25 times. The arrows mark the bursts corresponding to the frames A–C. Because switching off as well as bleaching is a truly stochastic process, it is unknown whether the molecule was in its dark state or bleached after the recording.

Cryosections of cytoplasmic membrane labeled E. coli

To label the cytoplasmic membrane with the RSFP rsFastLime, we expressed a fusion protein consisting of the M13 bacteriophage procoat protein fused to rsFastLime. M13 is integrated into the cytoplasmic membrane. It has two membrane-spanning domains with both termini reaching into the cytoplasm. The coding sequence for rsFastLime (15) was PCR amplified and inserted into a modified pET28 expression vector harboring a M13-GFP fusion (20) to replace the GFP coding sequence. The fusion protein was expressed in SURE E. coli cells (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA).

Thin cryosections were prepared as described previously (21,22). E. coli cells were fixed with 2% PFA (1 vol growth medium + 1 vol 4% (w/v) PFA) for 30 min at room temperature. After centrifugation, cells were postfixed with 4% and 0.1% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 2 h on ice. After being washed twice with PBS-0.02% glycine, cells were embedded in 10% gelatin, cooled on ice, and cut into small blocks. The blocks were infused with 2.3 M sucrose in PBS at 4°C overnight, mounted on metal pins and frozen in liquid nitrogen. 200-nm sections were cut at ∼−110°C using a diamond knife (Diatome, Biel, Switzerland) in an ultracryomicrotome (Leica Microsystems, Germany) and collected using a 1:1 mixture of 2.3 M sucrose (23) and 2% methyl-cellulose containing 40 mM Cysteamine (BioChemika, ≥98.0% (RT) (Sigma-Aldrich)). The cryosections were deposited on electric glow discharge (minus) treated coverslips, which were rinsed beforehand with deionized water for 5 min and cleaned in a low pressure plasma system (Femto-RF, Diener Electronic, Nagold, Germany). The mixture of methyl cellulose and sucrose which completely covered the sample was removed mechanically. A PBS (pH 7.4) based solution with 0.045% (v/v) Fluospheres (FluoSpheres carboxylate-modified microspheres, 0.2 μm, Nile red fluorescent (535/575) × 2% solids, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 0.09% (w/v) Polyvinyl alcohol was prepared. A 40-μl aliquot of the solution was pipetted onto the sample spinning at 3000 rpm in a spin-coating apparatus.

The final image was generated by analyzing 70,000 frames. The overall image acquisition time was 140 s (500 frames/s) and the light intensity (488 nm) was 5.0 kW/cm2.

α-Tubulin stained PtK2 cells

PtK2 cells were grown as described previously (24). Cells were seeded on coverslips (Menzel, Braunschweig, Germany) in a six-well plate (Nunc, Wiesbaden, Germany) and grown to a confluency of ∼80%.

For immunofluorescence labeling, cells were fixated for 4–6 min in ice-cold methanol and subsequently blocked for 10 min in PBS containing 1% BSA (blocking buffer). Cells were incubated with primary antibodies (2 μg/ml, anti-α-tubulin mouse IgG biotin conjugated, Invitrogen) diluted in blocking buffer at room temperature for 1 h followed by PBS washes and 5 min blocking in blocking buffer. For bridging the biotinylated anti-α-tubulin antibody with biotinylated rsFastLime, cells were incubated with Neutravidin (10 μg/ml, Invitrogen) at room temperature for 1 h followed by a short fixation with 3.7% PFA at room temperature for 5 min and subsequent PBS washes. Finally, cells were incubated with biotinylated rsFastLime (50 μg/ml, FluoReporter Mini-biotin-XX Protein Labeling Kit, Invitrogen) at room temperature for 1 h.

For sample preparation, a PBS-based solution with 0.045% (v/v) Fluospheres, 0.09% (w/v) Polyvinyl alcohol, and 0.29% (w/v) L-ascorbic acid was prepared. The pH was adjusted to 7.4–7.5. A 15-μl aliquot of this solution was pipetted onto the sample, which was then spin-coated for 40 s at 3000 rpm.

The final image was generated by analyzing 60,000 frames. The overall image acquisition time was 120 s (500 frames/s) and the light intensity (488 nm) was increased stepwise from 3.5 kW/cm2 to 5.0 kW/cm2.

RESULTS

Our setup (Fig. 1) consists of a light source for excitation, which may be complemented by another one for activation, and a CCD camera imaging the sample at a certain frame rate f. The imaging speed is determined by the number of molecular coordinates retrieved per second and thus by the activation rate, while the resolution depends on the unambiguous assignment of detected photons to single molecules. The density of activated fluorophores has to be low enough to avoid simultaneous bursts from molecules with overlapping images on the camera.

The number of emitted photons before deactivation or bleaching and thus the achievable resolution is a constant for moderate excitation intensities I, while the average on-time of a molecule, ton, is proportional to 1/I. The imaging speed can therefore be dramatically increased by simultaneously increasing I and the camera frame rate f such that ton ≈ 1/f, thus maintaining the highest activation density allowing reliable assignment of photons to individual molecules. PALMIRA also reduces background noise to a minimum: While frame rates faster than 1/ton spread bursts over several frames, increasing readout noise, slower frame rates would result in additional accumulation of background.

We used a fast CCD camera that allowed us to compress the readout process to several milliseconds. Fig. 3 shows three typical recordings of a sparse sample of the reversible photoswitchable protein rsFastLime (15) at a frame rate of 500 Hz. At this rather high frequency, our camera still operated at 97% duty cycle. The excellent signal/noise ratio of the data is evident in the time trace (Fig. 3 E). The root-mean-square of the combined background and readout noise typically averaged to <1 photon/pixel.

The data shown in Fig. 3 were recorded under pure 488 nm irradiation, which not only switches off dyes in the process of fluorescence reading but also activates dark molecules. Therefore, a dynamic equilibrium is formed during image acquisition with most of the molecules in the dark state and a small fraction of the molecules in the bright state. This fraction can be estimated from our single molecule experiments as the number of frames in which the molecule is visible, divided by the frame number of the last occurrence of such a burst from the molecule. The analysis of >600 time traces showed that the dynamic equilibrium keeps <0.2% of the rsFastLime molecules in their bright state.

This activation crosstalk keeps PALMIRA simple because, unlike in PALM or STORM, only a single laser line is used for activation and readout. Activation now occurs at arbitrary times during image acquisition, making the synchronization of illumination and image acquisition redundant. However, an activation density of 0.2% might be too high for some dense samples and would have to be reduced either by prebleaching some of the molecules or if possible by using a different excitation wavelength at which the action crosstalk between excitation and activation is different. If the activation density is lower than optimal, image acquisition can be accelerated by applying auxiliary activation light of a different wavelength. Alternatively, one can increase the excitation intensity beyond the optimum (ton < 1/f) at the expense of noise.

To explore the capabilities of PALMIRA, we first imaged 200-nm-thick cryosections of E. coli whose cytoplasmic membrane was labeled with rsFastLime (Fig. 4). We obtained the image by dividing the field of view into 20 nm pixels. Each time a molecule was located within the corresponding image region, that was brighter than the threshold, the pixel value was incremented by one. Note that this image assembly differs from that in Betzig et al. (10). In the latter the image is formed by plotting a Gaussian around each fitted position, with the standard deviation equaling the fit uncertainty. We have not followed this procedure because it tends to suggest more dynamic range than actually conveyed by the number of molecules detected. In Fig. 4 B, the dynamic range directly reflects the real number of events. In all experiments the number of photons per activation event followed geometrical distributions. In Fig. 4 B the threshold was adjusted to 22 photons tuning the resolution to an estimated 50 nm. Nonetheless, image acquisition times of ≈140 s yielded enough events to form clear images with sufficient dynamic range. Fig. 4 B shows that several bacteria can be identified. Their membranes are much more clearly resolved than in the conventional image from the same sample (Fig. 4 A).

There is no fundamental reason for this method to be limited to (ultra)thin samples. As long as the number of addressable molecules per unit area is small enough and these molecules are located inside a section where the shape of the PSF does not significantly change, it is also possible to record data inside whole cells or even thicker samples.

As a matter of fact, operating at the optimal frame rate and hence being less susceptible to background, PALMIRA allowed us to image stained α-tubulin inside whole PtK2 cells. Fig. 5 compares wide-field (Fig. 5 A) and PALMIRA (Fig. 5 B) recordings of the same area inside the cell. While individual microtubules are not resolved in the conventional image they can be clearly distinguished in the PALMIRA recording. The resolution is even high enough to pinpoint the somewhat inhomogeneous labeling along the filaments.

The distribution of detected photons per event for the data presented in Fig. 5 is shown in Fig. 5 E. Due to the threshold of 1.5 photons in the CLEAN algorithm, detection of events with a small number of photon counts was significantly less probable. For large photon counts per event (>30), the histogram approximately follows a geometrical distribution with an expectation value of ≈21 photons. To estimate the resolution, we scrutinized the object indicated in Fig. 5 B showing an agglomeration of several rsFastLime proteins. The averaged x- and y-profiles (Fig. 5, C and D) reveal that the resolution can be tuned to ≈40 nm by only choosing events with 35 photons or more for the data representation. Note that the “gray values” in our images represent the number of single molecule events per pixel. Hence the resolution directly results from the statistics of recording many events. Higher thresholds would improve the resolution further but reduce the dynamic range.

DISCUSSION

In summary, we demonstrated nanoscale far-field fluorescence imaging based on reversible photoswitching and detecting the photon bursts of individual molecules with recording times of 2–2.5 min. These advancements are due to an asynchronous laissez-faire protocol of data acquisition that just matches the camera acquisition time to the duration of the photon bursts. The 100-fold cut-down in recording time as compared to previous experiments lessens the requirements on long-term stability of the setup. Dedicated background suppression techniques such as total internal reflection fluorescence imaging are no longer generally required for single-molecule, localization-based applications. The use of a standard epifluorescence setup consequently allowed us to image features inside whole cells.

It is possible that a molecule is counted more than once in our image. This is because the utilized protein is reversibly switchable and because a single burst of emission may be spread over two or more camera frames. However, the overcounting probability is the same for every molecule, ensuring that the image is an unbiased representation of the fluorophore concentration in the sample. Controlling or knowing the average number of total counts of a molecule is not required. An advantage of reversible switching is that molecules that have emitted too few photons to be registered have another chance to finally contribute to the image. Time-lapse microscopy using PALMIRA will probably benefit from reversibility, because the labeling density is much less altered after the recording. Nonetheless, PALMIRA would work equally well with irreversible switches.

In the future, individual planes inside a thicker sample will selectively be activated and imaged. This can be accomplished, for example, by multiphoton-induced activation processes. By utilizing three-dimensional position determination techniques inside these individual planes, and by combining the information from several planes, it will be possible to obtain subdiffraction three-dimensional images of, e.g., whole cells, organelles, or transparent nonbiological samples.

Higher threshold values improve the resolution at the expense of dynamic range or imaging speed. This possibility will be partially limited by the geometrical distribution of the emitted photons in a burst. Since the main factor determining the image sharpness is the label itself, the development and use of other (reversibly) switchable fluorophores with stronger photon bursts will directly result in sharper images. Our frame acquisition time of 2 ms is sufficient to collect even 100-times more photons per burst, which will lead to an overall resolution of ≈4 nm. Still, the use of faster detectors will accelerate PALMIRA imaging even further.

Limiting the amount of crosstalk in prospective markers is of major importance, because it will allow the imaging of dense samples without prior bleaching. The speed of the switching process itself remains of minor importance because in our asynchronous recording protocol it has no influence on the total acquisition time. Finally, our results once more underscore the huge potential of molecular photoswitching for nanoscale imaging with visible light and regular lenses.

Acknowledgments

We thank J.-W. L. de Gier, Stockholm University, Sweden, for providing us with the expression vector harboring the M13-GFP fusion and Tim Salditt, Institute for X-Ray Physics, Göttingen University, for the use of the plasma system. We also thank Sylvia Löbermann, Rainer Pick, Jaydev Jethwa, and Donald Ouw for technical assistance, Michael Hoffmann for valuable discussions, and Brian Rankin for proofreading the manuscript.

Funding by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Research Center Molecular Physiology of the Brain and the European Union grant SPOTLITE is acknowledged.

Editor: Feng Gai.

References

- 1.Hell, S. W. 1994. Improvement of lateral resolution in far-field light microscopy using two-photon excitation with offset beams. Opt. Commun. 106:19–22. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hell, S. W., and J. Wichmann. 1994. Breaking the diffraction resolution limit by stimulated emission: stimulated emission depletion microscopy. Opt. Lett. 19:780–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hell, S. 2003. Toward fluorescence nanoscopy. Nat. Biotechnol. 21:1347–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bobroff, N. 1986. Position measurement with a resolution and noise-limited instrument. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 57:1152–1157. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Betzig, E. 1995. Proposed method for molecular optical imaging. Opt. Lett. 20:237–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hell, S. W., J. Soukka, and P. E. Hänninen. 1995. Two- and multiphoton detection as an imaging mode and means of increasing the resolution in far-field light microscopy. Bioimaging. 3:65–69. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt, T., G. J. Schutz, W. Baumgartner, H. J. Gruber, and H. Schindler. 1996. Imaging of single molecule diffusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 93:2926–2929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lacoste, T., X. Michalet, F. Pinaud, D. Chemla, A. Alivisatos, and S. Weiss. 2000. Ultrahigh-resolution multicolor colocalization of single fluorescent probes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:9461–9466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michalet, X., T. D. Lacoste, and S. Weiss. 2001. Ultrahigh-resolution colocalization of spectrally separable point-like fluorescent probes. Methods. 25:87–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Betzig, E., G. Patterson, R. Sougrat, O. Lindwasser, S. Olenych, J. Bonifacino, M. Davidson, J. Lippincott-Schwartz, and H. Hess. 2006. Imaging intracellular fluorescent proteins at nanometer resolution. Science. 313:1642–1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hess, S. T., T. P. K. Girirajan, and M. D. Mason. 2006. Ultra-high resolution imaging by fluorescence photoactivation localization microscopy. Biophys. J. 91:4258–4272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rust, M. J., M. Bates, and X. Zhuang. 2006. Sub-diffraction-limit imaging by stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM). Nat. Methods. 3:793–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hell, S. W. 2007. Far-field optical nanoscopy. Science. 316:1153–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moerner, W. E. 2006. Single-molecule mountains yield nanoscale cell images. Nat. Methods. 3:781–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stiel, A. C., S. Trowitzsch, G. Weber, M. Andresen, C. Eggeling, S. W. Hell, S. Jakobs, and M. C. Wahl. 2007. 1.8 Å bright-state structure of the reversibly switchable fluorescent protein Dronpa guides the generation of fast switching variants. Biochem. J. 402:35–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ando, R., H. Mizuno, and A. Miyawaki. 2004. Regulated fast nucleocytoplasmic shuttling observed by reversible protein highlighting. Science. 306:1370–1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geisler, C., A. Schönle, C. von Middendorff, H. Bock, C. Eggeling, A. Egner, and S. W. Hell. 2007. Resolution of λ/10 in fluorescence microscopy using fast single molecule photo-switching. Appl. Phys. A. 88:223–226. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hogbom, J. 1974. Aperture synthesis with a non-regular distribution of interferometer baselines. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 15:417–426. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson, R., D. Larson, and W. Webb. 2002. Precise nanometer localization analysis for individual fluorescent probes. Biophys. J. 82:2775–2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drew, D. E., G. von Heijne, P. Nordlund, and J. W. de Gier. 2001. Green fluorescent protein as an indicator to monitor membrane protein overexpression in Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 507:220–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tokuyasu, K. T. 1973. A technique for ultracryotomy of cell suspensions and tissues. J. Cell Biol. 57:551–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tokuyasu, K. T. 1980. Immunochemistry on ultrathin frozen sections. Histochem. J. 12:381–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liou, W., H. J. Geuze, and J. W. Slot. 1996. Improving structural integrity of cryosections for immunogold labeling. Histochem. Cell Biol. 106:41–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osborn, M., W. W. Franke, and K. Weber. 1977. Visualization of a system of filaments 7–10 nm thick in cultured cells of an epithelioid line (Pt K2) by immunofluorescence microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 74:2490–2494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]