Abstract

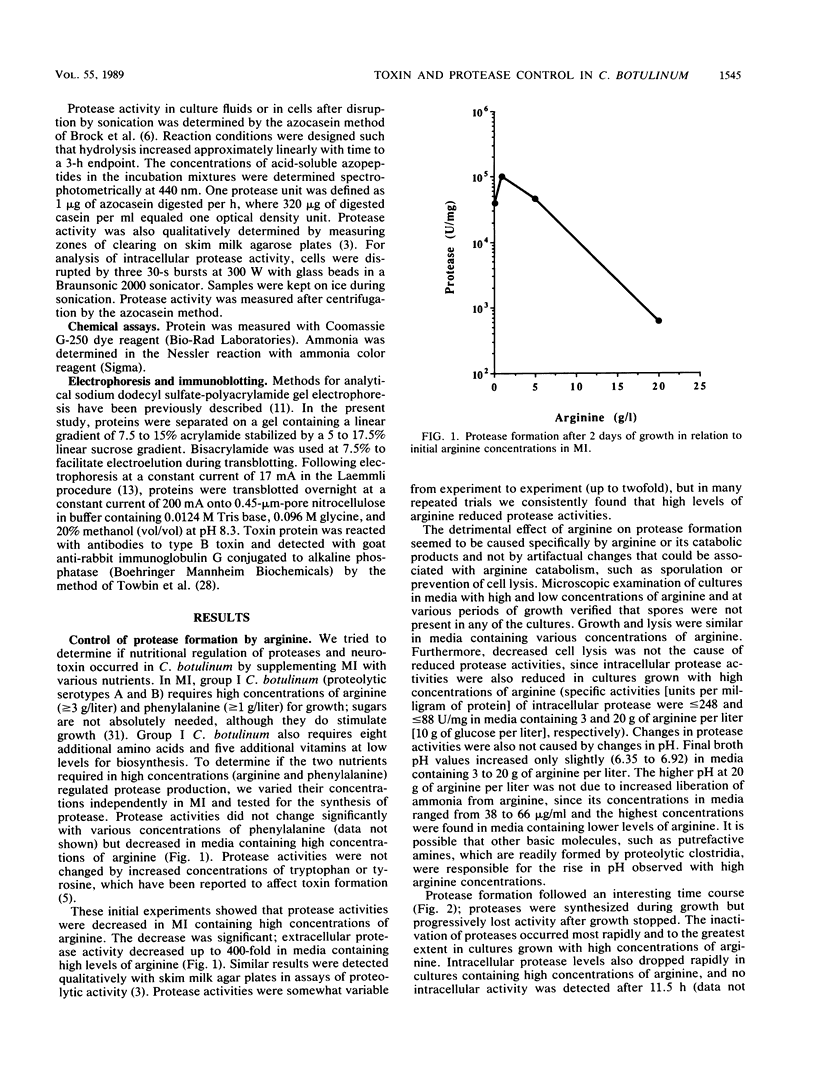

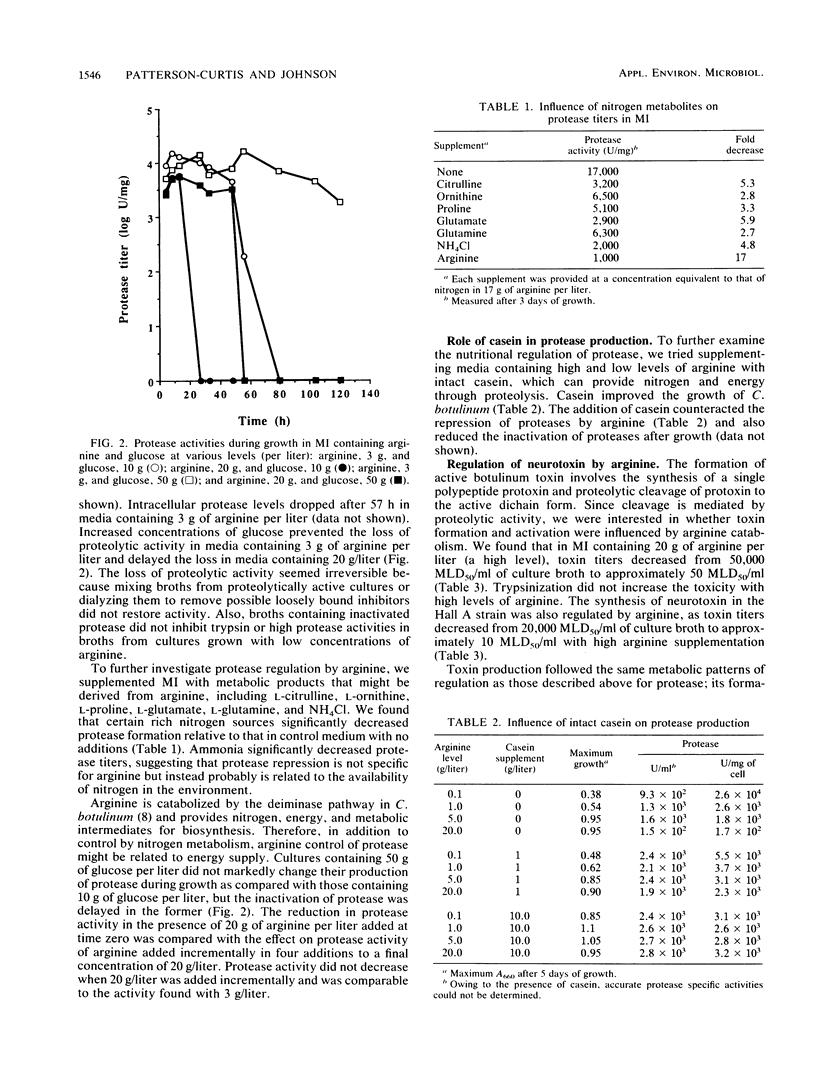

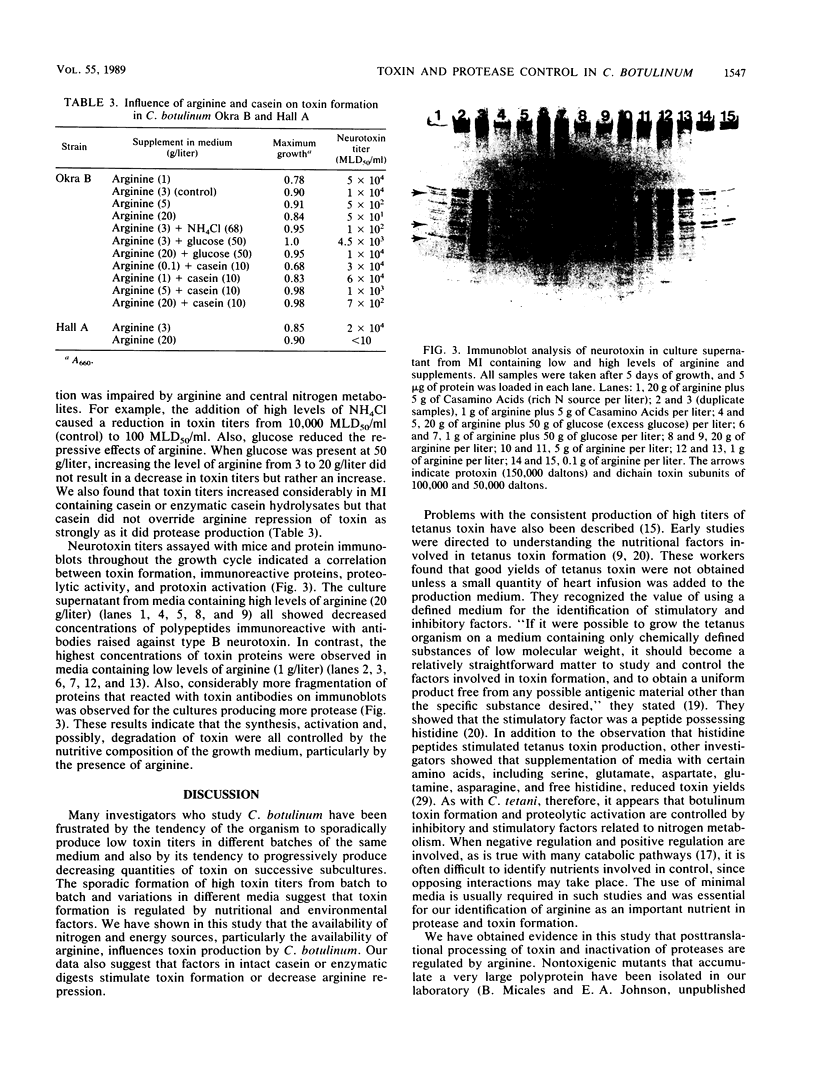

Supplementation of a minimal medium with high levels of arginine (20 g/liter) markedly decreased neurotoxin titers and protease activities in cultures of Clostridium botulinum Okra B and Hall A. Nitrogenous nutrients that are known to be derived from arginine, including proline, glutamate, and ammonia, also decreased protease and toxin but less so than did arginine. Proteases synthesized during growth were rapidly inactivated after growth stopped in media containing high levels of arginine. Separation of extracellular proteins by electrophoresis and immunoblots with antibodies to toxin showed that the decrease in toxin titers in media containing high levels of arginine was caused by both reduced synthesis of protoxin and impaired proteolytic activation. In contrast, certain other nutritional conditions stimulated protease and toxin formation in C. botulinum and counteracted the repression by arginine. Supplementation of the minimal medium with casein or casein hydrolysates increased protease activities and toxin titers. Casein supplementation of a medium containing high levels of arginine prevented protease inactivation. High levels of glucose (50 g/liter) also delayed the inactivation of proteases in both the minimal medium and a medium containing high levels of arginine. These observations suggest that the availability of nitrogen and energy sources, particularly arginine, affects the production and proteolytic processing of toxins and proteases in C. botulinum.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Arnon S. S. Infant botulism: anticipating the second decade. J Infect Dis. 1986 Aug;154(2):201–206. doi: 10.1093/infdis/154.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BONVENTRE P. F., KEMPE L. L. Physiology of toxin production by Clostridium botulinum types A and B. II. Effect of carbohydrate source on growth, autolysis, and toxin production. Appl Microbiol. 1959 Nov;7:372–374. doi: 10.1128/am.7.6.372-374.1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker H. A. Amino acid degradation by anaerobic bacteria. Annu Rev Biochem. 1981;50:23–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.50.070181.000323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock F. M., Forsberg C. W., Buchanan-Smith J. G. Proteolytic activity of rumen microorganisms and effects of proteinase inhibitors. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982 Sep;44(3):561–569. doi: 10.1128/aem.44.3.561-569.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunin R., Glansdorff N., Piérard A., Stalon V. Biosynthesis and metabolism of arginine in bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1986 Sep;50(3):314–352. doi: 10.1128/mr.50.3.314-352.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FISEK N. H., MUELLER J. H., MILLER P. A. Muscle extractives in the production of tetanus toxin. J Bacteriol. 1954 Mar;67(3):329–334. doi: 10.1128/jb.67.3.329-334.1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GROSSOWICZ N., KINDLER S. H., MAGER J. Toxin production by Clostridium parabotulinum type A. J Gen Microbiol. 1956 Oct;15(2):394–403. doi: 10.1099/00221287-15-2-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J. D., McCroskey L. M., Pincomb B. J., Hatheway C. L. Isolation of an organism resembling Clostridium barati which produces type F botulinal toxin from an infant with botulism. J Clin Microbiol. 1985 Apr;21(4):654–655. doi: 10.1128/jcm.21.4.654-655.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer B. A., Johnson E. A. Purification, properties, and metabolic roles of NAD+-glutamate dehydrogenase in Clostridium botulinum 113B. Arch Microbiol. 1988;150(5):460–464. doi: 10.1007/BF00422287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LATHAM W. C., BENT D. F., LEVINE L. Tetanus toxin production in the absence of protein. Appl Microbiol. 1962 Mar;10:146–152. doi: 10.1128/am.10.2.146-152.1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970 Aug 15;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamanna C., Spero L., Schantz E. J. Dependence of time to death on molecular size of botulinum toxin. Infect Immun. 1970 Apr;1(4):423–424. doi: 10.1128/iai.1.4.423-424.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis K. H., Hill E. V. Practical Media and Control Measures for Producing Highly Toxic Cultures of Clostridium botulinum, Type A. J Bacteriol. 1947 Feb;53(2):213–230. doi: 10.1128/jb.53.2.213-230.1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILLER P. A., MUELLER J. H. Essential role of histidine peptides in tetanus toxin production. J Biol Chem. 1956 Nov;223(1):185–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magasanik B. Classical and postclassical modes of regulation of the synthesis of degradative bacterial enzymes. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1976;17:99–115. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCroskey L. M., Hatheway C. L., Fenicia L., Pasolini B., Aureli P. Characterization of an organism that produces type E botulinal toxin but which resembles Clostridium butyricum from the feces of an infant with type E botulism. J Clin Microbiol. 1986 Jan;23(1):201–202. doi: 10.1128/jcm.23.1.201-202.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller J. H., Miller P. A. Growth Requirements of Clostridium tetani. J Bacteriol. 1942 Jun;43(6):763–772. doi: 10.1128/jb.43.6.763-772.1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg E., Keller K. H., Dworkin M. Cell density-dependent growth of Myxococcus xanthus on casein. J Bacteriol. 1977 Feb;129(2):770–777. doi: 10.1128/jb.129.2.770-777.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson L. L. Molecular pharmacology of botulinum toxin and tetanus toxin. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1986;26:427–453. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.26.040186.002235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TSUNASHIMA I., SATO K., SHOJI K., YONEDA M., AMANO T. EXCESS SUPPLEMENTATION OF CERTAIN AMINO ACIDS TO MEDIUM AND ITS INHIBITORY EFFECT ON TOXIN PRODUCTION BY CLOSTRIDIUM TETANI. Biken J. 1964 Dec;7:161–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin H., Staehelin T., Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979 Sep;76(9):4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellink J., van Kammen A. Proteases involved in the processing of viral polyproteins. Brief review. Arch Virol. 1988;98(1-2):1–26. doi: 10.1007/BF01321002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmer M. E., Johnson E. A. Development of improved defined media for Clostridium botulinum serotypes A, B, and E. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988 Mar;54(3):753–759. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.3.753-759.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]