Abstract

Rapid neurotransmission is mediated through a superfamily of Cys-loop receptors, that includes the nicotinic acetylcholine (nAChR), γ-aminobutyric-acid (GABAA/C), serotonin (5-HT3) and glycine receptors. A class of ligands, including galanthamine, local anesthetics and certain toxins, interact with nAChRs non-competitively. Suggested modes of action include blockade of the ion-channel, modulation from as yet undefined extracellular sites, stabilization of desensitized states, and association with annular or boundary lipid. Alignment of mammalian Cys-loop receptors show aromatic residues, found in the acetylcholine or ligand binding pocket of nAChRs, are conserved in all subunit interfaces of neuronal nAChRs, including subunit interfaces that are not formed by α subunits on the principal side of the transmitter binding site. The amino terminal domain containing the ligand recognition site is homologous to the soluble acetylcholine binding protein (AChBP) from mollusks, an established structural and functional surrogate. Herein we assess ligand specificity and employ X-ray crystallography with AChBP to demonstrate ligand interactions at subunit interfaces lacking vicinal cysteines (i.e., the non-α subunit interfaces in nAChRs). Non-competitive nicotinic ligands bind AChBP with high affinity (KD’s of 0.015 to 6 μM). We mutated the vicinal cysteines in loop C of AChBP to mimic the non-alpha subunit interfaces of neuronal nAChRs and other Cys loop receptors. Classical nicotinic agonists show a 10 to 40-fold reduction in binding affinity, whereas binding of ligands known to be non-competitive are not affected. X-ray structures of cocaine and galanthamine bound to AChBP (1.8 and 2.9 Å resolution respectively) reveal interactions deep within the subunit interface and the absence of a contact surface with the tip of loop C. Hence, in addition to channel blocking, non-competitive interactions with heteromeric neuronal nAChR appear to occur at the non-alpha subunit interface, a site presumed to be similar to that of modulating benzodiazepines on GABAA receptors.

Keywords: non-competitive inhibitors, nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, acetylcholine binding protein, benzodiazepine, galanthamine, cocaine

Cys-loop receptors activating ion flow are pentameric proteins composed of a large amino-terminal extracellular ligand binding domain, a stretch of three membrane-spanning segments, a cytoplasmic domain, following by a fourth transmembrane span1. Neurotransmitters, by binding to an extracellular site, allosterically gate the flow of ions through the channel. In nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChR), acetylcholine (ACh) binds at a well defined pocket lined with aromatic residues. It is located at an interface formed with an α subunit containing an overlapping loop with vicinal cysteines and the opposite face of a partnering subunit. Ligands that compete with ACh or α-bungarotoxin (bgtx) at this site are agonists or competitive antagonists; ligands influencing channel opening, but not competing with ACh and bgtx, are non-competitive ligands. Heteromeric receptors form subunit interfaces lacking a α subunit with vicinal cysteines on its principal face. These ‘non-alpha’ interfaces are not known to bind ACh or bgtx.

Non-competitive ligands interact with nAChR at sites distinct from the competitive ligand binding pocket1; 2, conferring multiple modes of action (Figure 1a). Channel blockers, including phencyclidine (PCP), quinacrine, and QX222, are among the best characterized non-competitive ligands. Photolabeling of Torpedo nAChRs with chlorpromazine localized a non-competitive binding region to the membrane spanning M2 helix outlining the transmembrane pore3. Other compounds have been shown to label this region, and their incorporation is diminished by the addition of PCP4; 5. The structural position of the labeled residues for these receptors is consistent with this site blocking the flow of ions6; 7; 8. Less well defined sites are those found for non-competitive inhibitors not occupying the channel9; 10; 11; 12 and potential positive allosteric modulators2; 13; 14.

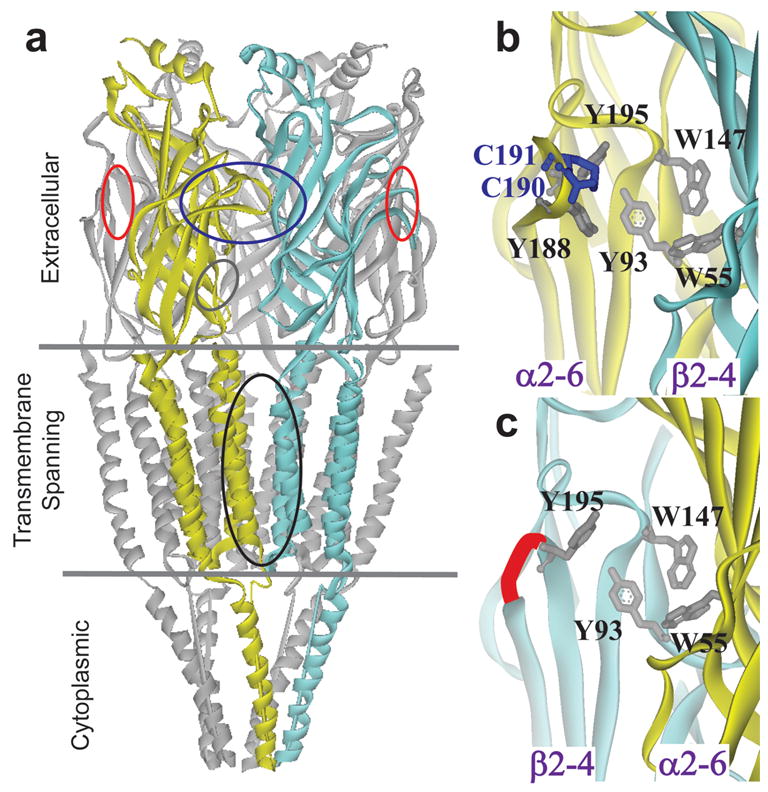

Figure 1.

Non-competitive ligand binding sites: a, Subunit interface of a full length nAChR28; 37; 38. Ovals indicate binding location of channel blockers (black), competitive ligands (blue), non-alpha sites (red) and positive modulators (grey oblique) b, The competitive binding pocket of AChBP19; 28; 38 containing 5 aromatic residues and bonded vicinal cysteines (shown as grey and blue sticks respectively). c, Non-alpha subunit interface of a neuronal nicotinic (adapted from crystal AChBP structure28). Conserved aromatic residues are shown as grey sticks. A red connection indicates a shortened amide backbone link that replaces the vicinal cysteine region in loop C of neuronal β subunits.

C-Loop Modification and AChBP Ligand Affinity

The acetylcholine binding protein (AChBP) is a soluble homopentamer homologous to the extracellular domain of nAChRs and contains all ligand binding determinants for competitive nicotinic agonists and antagonists15; 16. When its cDNA, encoding minor structural changes and a chimeric link to a transmembrane domain from the Cys loop receptor family, is expressed, the chimeric AChBP-receptor is capable of gating ions17. The absence of a transmembrane domain in AChBP allows one to investigate potential competitive and non-competitive extracellular binding determinants by physical methods. Furthermore, AChBP-ligand complexes are amenable to structural studies at atomic resolution with X-ray crystallography.

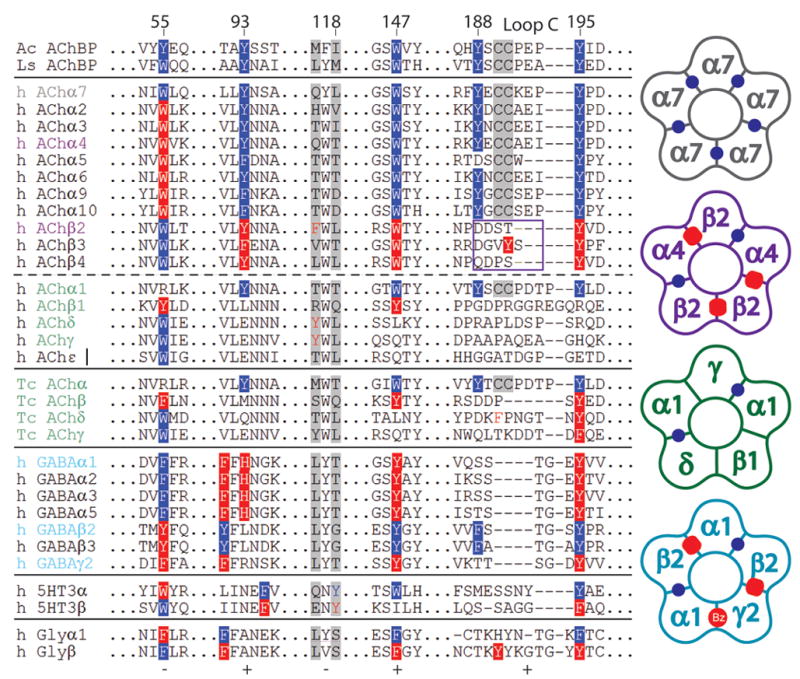

To this end, we used AChBP from the mollusk, Aplysia californica16. Ligand binding was examined by competition with a variety of nicotinic non-competitive antagonists and candidate positive modulators. Dissociation constants ranged from 0.015 to 6 μM (see Figure 2 and Table 1). Previously, we and others identified structural determinants for a range of agonists and antagonists delineating the competitive ligand binding site18; 19. Important residues are highlighted in an alignment of amino acid sequences of the extracellular domain of human Cys-loop receptors (Figure 3). The essential interfacial binding site, typically bounded by 4–5 aromatic residues provided by the two subunits, is conserved in all interfaces where agonists bind (Figure 3 blue shading). The side chain aromatic groups are also conserved in the non-alpha interfaces of human neuronal receptors, but not in muscle or in Torpedo (Figure 3 red shading). This site resembles a benzodiazepine site thought to be a positive modulatory site in GABAA receptors20 (Figure 3 right cartoon).

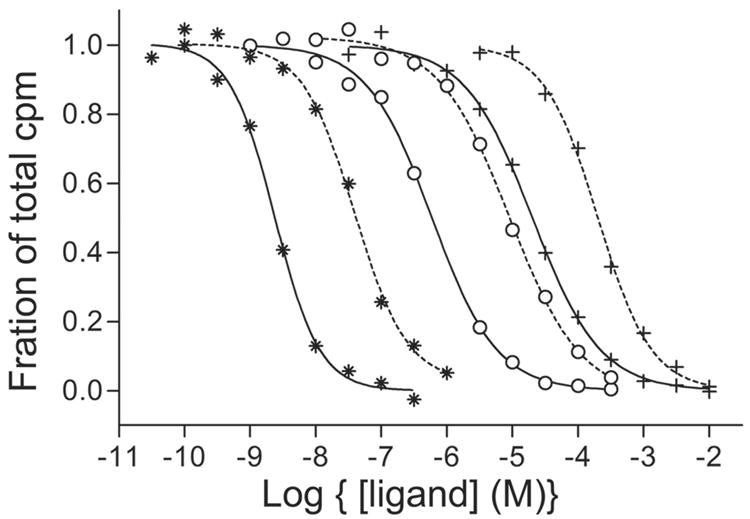

Figure 2.

Radioligand binding profiles. Wild type (wt) (solid line) and C190A+C191A (dotted line) ●-epibatidine, ○-nicotine, *-acetylcholine. These ligands were competed against 20 nM 3H Strychnine as the reference ligand. Binding curves for non-competitive ligands were similar with little difference between wt and mutant.

Table 1.

Ligand Binding Constants for Aplysia californica AChBP

| Wildtype† |

C190/191A† |

Ratio

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-competitive | Kd* (μM) | SEM | Kd* (μM) | SEM | mt/wt |

| Strychninen | 0.015 | 0.006 | 0.016 | 0.006 | 1.1 |

| TCPn,^ | 0.78 | 0.1 | 2.3 | 0.01 | 3.8 |

| Galanthaminep | 1.3 | 0.04 | 2.1 | 0.1 | 1.6 |

| Cocainen | 1.8 | 0.6 | 2.1 | 0.7 | 1.2 |

| Codeinep | 3.6 | 0.2 | 5.0 | 0.005 | 1.4 |

| Morphinen | 6.1 | 0.5 | 4.9 | 0.08 | 0.8 |

|

| |||||

|

Competitive

| |||||

| Acetylcholinea | 4.4 | 0.6 | 52 | 3.0 | 12 |

| Nicotinea | 0.055 | 0.003 | 0.97 | 0.23 | 18 |

| Epibatidinea | 0.00032 | 0.00003 | 0.012 | 0.002 | 38 |

contains the Y55W mutation found in the human receptors

non-competitive antagonist

positive modulator

competitive agonist

N-(1-(2 Thienyl)cyclohexyl)-3,4-piperdine

Dissociation constants (Kd) were determined by competition with3H- strychnine in a scintillation proximity assay (Amersham) and are the mean of typically three experiments. Substitution of serines at 190 and 191 for cysteines yielded similar Kd’s to the alanine mutations.

Figure 3.

Non-alpha interfaces of Cys-loop receptors. Left, residues on the principal (+) (93,147, 188, 195) and complementary (−) (55, 118) faces within 3.5 Å of bound ligand are highlighted. Aromatic resides at a competitive α subunit interface are shown on a blue background and residues forming a non-alpha interface are shown on a red background. For nAChRs, the core aromatic pocket forming residues, typically 4 to 5, are found in all competitive alpha subunits and in all of the non-alpha interfaces of neuronal receptors, but not non-alpha interfaces of Torpedo or human muscle nAChRs. 5HT3, GABA, and glycine, (Gly) receptors contain homologous π pockets with varied aromatic residues. A box indicates the tip of loop C in a non-alpha interface of neuronal nAChRs. Right, cartoon schematic depicting the competitive (blue dots) and non-alpha (red ovals) interfaces of nAChR α7 (grey), nAChR α4β2 (purple), Torpedo/human muscle receptors (green), and GABA α1β2γ2 receptors (cyan). Coloring corresponds to subunit composition on the left.

We reasoned that non-competitive ligands might bind at a non-alpha interface of heteromeric neuronal nAChRs. To test this hypothesis, we substituted alanine or serine for both of the vicinal cysteines in loop C of AChBP, therein yielding a sequence similar to the β subunit of neuronal nAChRs and other Cys loop receptors (Figure 1c and 3). These mutations caused decreases in affinities (10–40 fold) for all agonists studied, (cf:ref21), but no significant decrease in affinities for classical non-competitive nicotinic ligands (Table 1).

Crystal Structures of the Cocaine and Galanthamine Complexes

To determine the structural binding determinants of non-competitive nicotinic ligands, we co-crystallized Aplysia AChBP with cocaine or galanthamine and obtained crystals that diffracted to 1.8 and 2.9 Å, respectively. Cocaine and galanthamine bound AChBP structures refined to a % Rcryst (Rfree) of 18(21) and 21(24), respectively. (See Supplemental Information for full statistics.) In agreement with their ligand binding properties, cocaine and galanthamine both associate at these subunit interfaces. No other binding site was apparent from the crystal structures (Figure 4a–b). For the cocaine complex, two of the five binding sites contained clear electron density for the ligand. A third subunit interface contained density for a mixture of cocaine and PEG and the remaining two interfaces contained mostly PEG. Galanthamine bound in two conformations in four of five subunits. The fifth subunit contained a small, 8 carbon, PEG molecule.

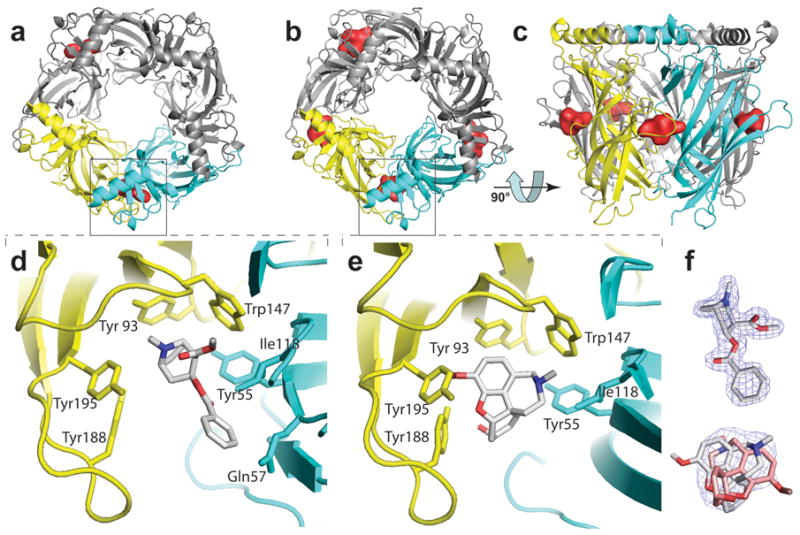

Figure 4.

X-ray Crystal Structures of Cocaine and Galanthamine (pdb accession code XXXX and XXXX respectively). The subunit interface is shown between two subunits colored yellow and cyan (+ and − face, respectively). Bound ligand surfaces are shown in red. a and b, Cocaine and galanthamine (respectively) bound AChBP viewed along the pore’s five fold symmetry axis. c, Pentamer with galanthamine bound viewed rotated by 90° from panel b orientation. d and e, Zoom of a and b (respectively) with no ligand surfaces shown. f, Bound ligand with electron density contoured at 1.5 sigma.

In contrast to several competitive agonists and antagonists16; 19, interactions with the vicinal cysteines, at the tip of loop C, appeared minimal for both galanthamine and cocaine. In all binding pockets that contained galanthamine, loop C packed against the ligand, but the vicinal cysteines were positioned away from the ligand (Figure 4e). Galanthamine bound in two conformations in equal proportions (Figure 4f). The amine nitrogen of galanthamine was situated between Trp 147 and either Tyr 93 or Tyr 55. In both orientations the polar oxygen atoms of galanthamine were oriented towards loop C. For the complex with cocaine, one subunit resulted in the vicinal cysteines contacting the benzene ring of cocaine (not shown). This configuration might be explained by crystal packing of the cysteines with a neighboring molecule. In a second subunit, where the cysteines lacked crystal contacts, loop C occupied two conformations, and the more abundant conformation resembled that of galanthamine with minimal interaction between cysteines and ligand (Figure 4d). Cocaine occupied the same bound position in both subunits. Hence, the tight packing of loop C involving contact of the ligand with the vicinal cysteines seen with competitive agonists and antagonist16; 19 is not evident.

The ability of cocaine and galanthamine to bind AChBP is governed foremost by the conserved tryptophans at the core of the aromatic pocket and to a lesser extent by Tyr 195 on loop C. This is evident from the proximity of the cationic moiety to these aromatic side chains and the carbonyl of Trp 149 in the crystal structures. The Asp 89 anionic side chain likely exerts an inductive influence on the carbonyl group of Trp 149 increasing the strength of the dipole that interacts with the protonated nitrogen in the ligand 19. Using a protein sequence alignment of Cys loop receptors, we compared the sequence of amino acids residues governing cocaine and galanthamine binding in AChBP to homologous residues in nAChRs (Figure 3). Excluding the tip of loop C, the sequence of amino acids contacting cocaine and galanthamine are conserved in both the competitive and non-alpha interfaces of heteromeric neuronal nAChRs; Asp 89 is invariant, and a conserved GSW149 motif is found in the non-α site proximal to the Asp 89 side chain. Hence, galanthamine and cocaine likely bind at both the competitive and non-alpha interfaces of neuronal nAChRs. This agrees well with analysis of ligand binding that have shown these ligands to bind both competitively and non-competitively in a concentration dependent manner13.

Galanthamine is known to modulate positively ligand binding to nAChRs22. Another positive modulator, diazepam, binds to GABAA receptors. Diazepam and other benzodiazepines are known to associate at subunit interfaces not occupied by the agonist20; 23 (Figure 3). Interestingly, our proposed site for galanthamine binding in nAChR is similar to the benzodiazepine interfacial site of GABAA receptors. While our data provide evidence that conserved residues at the non-alpha interface of nAChR are sufficient to form sites resembling that for benzodiazepines or other allosteric ligands, the homomeric nature of AChBP precludes the direct study of modulatory function or interaction between non-identical subunits. Nevertheless, our identification of non-competitive binding determinants suggests that the potential exists for positive modulation of nicotinic receptors at a non-alpha site. Similarities to GABAA also suggest that ligand binding is likely to be subunit interface specific; diazepam appears to only modulate at the α1-γ2 interfaces, as examined by binding specificity or a selective elicitation of a response upon ligand binding23.

Antagonism of nAChRs is more widespread than positive modulation and non-competitive antagonists have multiple modes of action. Many non-competitive ligands have a primary action that blocks the ion channel2; 13. Others are described as extra-channel non-competitive ligands2; 13. Our data suggest that cocaine is capable of binding at a non-alpha interface, but do not indicate whether its occupation is sufficient to antagonize function, since AChBP lacks a transmembrane domain. Interestingly, strychnine is non-competitive in α4β2 nicotinic receptors, but competitive in α7 receptors24; 25. This binding pattern is to be expected, for α7 has five competitive interfaces and lacks non-alpha interfaces found in α4β2 (Figure 3). Identifying a non-competitive binding site in the extracellular domain should help distinguish the functional contributions of the non-alpha interface from the channel blocking or the competitive antagonist sites. It is important to note here that the non-alpha interfaces of human muscle and Torpedo nAChRs lack the necessary 4–5 aromatic amino acids to make a surrounding aromatic nest (Figure 3 alignment). Hence, modulation by physostigmine (as well as galanthamine) in Torpedo, likely occurs at a site distinct from the non-alpha subunit interface, consistent with previous findings26; 27 (Figure 1a grey oval). Furthermore, we would predict that antagonism in the Torpedo or muscle systems would be influenced more by channel blockade than allosteric inhibition at a non-alpha subunit interface.

Loop C capping the agonist binding site senses ligand binding and its closure initiates as yet unclear conformational changes that influence channel gating18; 28. In both the cocaine and galanthamine structures, Loop C is extended radially, similar to the positions found for bound antagonists. The rigidity of the ring systems in both of these molecules may preclude a tight capping by Loop C on the principal face of the alpha subunit as seen for the agonists. However, at the non-alpha interfaces, not only is the vicinal disulfide in loop C not conserved, but several residues involved in the capping are deleted. Moreover, in the intact receptor, intersubunit interactions, reflected in cooperativity in the binding function and the state function for activation29, may be mediated through the transmembrane domains. Ligand association in AChBP has not been found to be cooperative, and this may indicate that intersubunit interactions do not solely involve the extracellular domain.

Conservation of aromatic residues at non-alpha subunit interfaces of neuronal receptors suggests an important functional role for the aromaticity. The absence of an aromatic cluster of side chains in muscle and Torpedo receptor subunits argues that a full complement of aromatic side chains is not a structural requirement for proper folding, subunit assembly, protein stability or cooperative agonist-elicited responses, since these features are present in muscle receptors. Rather a more likely role of the potential sites at the non-alpha interface is to regulate the influence of the agonist on gating. One potential non-competitive modulator that acts in this manner is lynx1, found endogenously in the central nervous system of mammals30. Lynx1 is structurally similar to α-bungarotoxin, yet modulates nicotinic receptors non-competitively. Given the similarities of important residues in both the competitive and non-alpha interfaces, lnyx1 might bind at this non-competitive interface.

Acetylcholine might also play a role at non-alpha interfaces. Removing the vicinal cysteines from loop C moderately affects agonist binding affinities. For acetylcholine in AChBP, the affinity decreased from a Kd of 4μM to 50 μM (Table 1). Hence, we can exclude ACh occupying non-alpha sites near the foot of the concentration-response curve. A possible function of a lower affinity acetylcholine site would be to decouple transmitter activation from desensitization by modulating the rate of desensitization.

The non-alpha interfaces of nAChRs represent potential therapeutic targets. In fact, non-alpha interfaces of nAChRs exhibit more variation in amino acid sequence than their competitive counterparts due to the high degree of sequence variation in loop C at non-alpha interfaces (Figure 3, box). The site will likely prove useful in developing subtype-selective compounds for studying receptor subtype assembly and localization. Future studies will be needed to show the functional consequences of ligand association at the non-alpha interface. If nAChRs behave as GABAA receptors, the potential exists to develop novel non-competitive therapeutics selective for nAChR subtypes. Provided selectivity can be achieved, such sites may be potentially beneficial targets in treating schizophrenia, nicotine addiction, Alzheimer’s disease, depression and pain.

Methods

A gene chemically synthesized from oligonucleotides encoding the soluble Aplysia AChBP was expressed in HEK293S cells lacking the N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase I (GnTI−)31 gene. AChBP was purified from the media as previously described 16; 28. Dissociation constants were determined by a scintillation proximity assay (Amersham Biosciences). Briefly, purified AChBP (100–200 nM sites) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, was mixed with SPA beads, log dilutions of drug, and 5–20 nM 3H strychnine or 3H epibatidine as a competing ligand (50 μl total volume). Samples were equilibrated for 1hr and assayed on a Beckman LS6500 scintillation counter.

Cocaine and galanthamine complexes with Aplysia AChBP were formed using 1mM ligand and 0.3–0.5 mM protein (10–15 mg/ml) at room temperature. Crystallization was achieved by vapor diffusion at 18° C using a protein-to-well ratio of 1:1 in 2μl hanging drops. The well solutions were: for the cocaine complex, 10% PEG-400, 15% PEG-1000, 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, and for the galanthamine complex, 10% PEG-1000, 24% isopropanol, 0.1 M sodium citrate, pH 5.6. The crystals were flash cooled in liquid nitrogen. Data were processed with HKL200032 and all further computing was carried out with the CCP4 suited program33.

All structures were solved by molecular replacement with AMoRe34, using as a search model the structure of Apo A-AChBP (PDB code 2BYN28). The initial electron density maps were improved considerably by manual adjustment with the graphics program Xtalview v4.135. All structures were refined with REFMAC36 using the maximum likelihood approach and incorporating bulk solvent corrections, anisotropic Fobs versus Fcalc scaling, and TLS refinement with each subunit defining a TLS group. NCS restraints were applied during refinement of the galanthamine complexed structures. Coordinates are deposited with the protein data bank; accession code XXXX for galanthamine and XXXX for cocaine.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to ALS (Berkeley, CA) and APS (Argonne, IL) staff for assistance in data collection, and to Todd Talley, Zoran Radic, Ryan Hibbs, Choel Kim, Susan Taylor and Andrew Hansen for scientific support and fruitful discussions. Supported by USPHS grants R37-GM18360/UO1-DA019372 (to P.T.) and a TRDRP and GM07752 fellowship (to S.B.H.)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Changeux J-P. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: from molecular biology to cognition. 1. Odile Jacob; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pereira EF, Hilmas C, Santos MD, Alkondon M, Maelicke A, Albuquerque EX. Unconventional ligands and modulators of nicotinic receptors. J Neurobiol. 2002;53:479–500. doi: 10.1002/neu.10146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giraudat J, Dennis M, Heidmann T, Chang JY, Changeux JP. Structure of the high-affinity binding site for noncompetitive blockers of the acetylcholine receptor: serine-262 of the delta subunit is labeled by [3H]chlorpromazine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:2719–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.8.2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oberthur W, Muhn P, Baumann H, Lottspeich F, Wittmann-Liebold B, Hucho F. The reaction site of a non-competitive antagonist in the delta-subunit of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Embo J. 1986;5:1815–9. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04431.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pedersen SE, Sharp SD, Liu WS, Cohen JB. Structure of the noncompetitive antagonist-binding site of the Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. [3H]meproadifen mustard reacts selectively with alpha-subunit Glu-262. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:10489–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cymes GD, Ni Y, Grosman C. Probing ion-channel pores one proton at a time. Nature. 2005;438:975–80. doi: 10.1038/nature04293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miyazawa A, Fujiyoshi Y, Unwin N. Structure and gating mechanism of the acetylcholine receptor pore. Nature. 2003;423:949–55. doi: 10.1038/nature01748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akabas MH, Stauffer DA, Xu M, Karlin A. Acetylcholine receptor channel structure probed in cysteine-substitution mutants. Science. 1992;258:307–10. doi: 10.1126/science.1384130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blanton MP, Xie Y, Dangott LJ, Cohen JB. The steroid promegestone is a noncompetitive antagonist of the Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor that interacts with the lipid-protein interface. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;55:269–78. doi: 10.1124/mol.55.2.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gumilar F, Arias HR, Spitzmaul G, Bouzat C. Molecular mechanisms of inhibition of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by tricyclic antidepressants. Neuropharmacology. 2003;45:964–76. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00247-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costa V, Nistri A, Cavalli A, Carloni P. A structural model of agonist binding to the alpha3beta4 neuronal nicotinic receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;140:921–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Francis MM, Vazquez RW, Papke RL, Oswald RE. Subtype-selective inhibition of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by cocaine is determined by the alpha4 and beta4 subunits. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:109–19. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arias HR, Bhumireddy P, Bouzat C. Molecular mechanisms and binding site locations for noncompetitive antagonists of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38:1254–76. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daly JW. Nicotinic agonists, antagonists, and modulators from natural sources. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2005;25:513–52. doi: 10.1007/s10571-005-3968-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smit AB, Syed NI, Schaap D, van Minnen J, Klumperman J, Kits KS, Lodder H, van der Schors RC, van Elk R, Sorgedrager B, Brejc K, Sixma TK, Geraerts WP. A glia-derived acetylcholine-binding protein that modulates synaptic transmission. Nature. 2001;411:261–8. doi: 10.1038/35077000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansen SB, Talley TT, Radic Z, Taylor P. Structural and ligand recognition characteristics of an acetylcholine-binding protein from Aplysia californica. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:24197–202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402452200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bouzat C, Gumilar F, Spitzmaul G, Wang HL, Rayes D, Hansen SB, Taylor P, Sine SM. Coupling of agonist binding to channel gating in an ACh-binding protein linked to an ion channel. Nature. 2004;430:896–900. doi: 10.1038/nature02753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao F, Bren N, Burghardt TP, Hansen S, Henchman RH, Taylor P, McCammon JA, Sine SM. Agonist-mediated conformational changes in acetylcholine-binding protein revealed by simulation and intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:8443–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412389200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Celie PH, van Rossum-Fikkert SE, van Dijk WJ, Brejc K, Smit AB, Sixma TK. Nicotine and carbamylcholine binding to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors as studied in AChBP crystal structures. Neuron. 2004;41:907–14. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ernst M, Brauchart D, Boresch S, Sieghart W. Comparative modeling of GABA(A) receptors: limits, insights, future developments. Neuroscience. 2003;119:933–43. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00288-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao F, Mer G, Tonelli M, Hansen SB, Burghardt TP, Taylor P, Sine SM. Solution NMR of acetylcholine binding protein reveals agonist-mediated conformational change of the C-loop. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:1230–5. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.027185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samochocki M, Hoffle A, Fehrenbacher A, Jostock R, Ludwig J, Christner C, Radina M, Zerlin M, Ullmer C, Pereira EF, Lubbert H, Albuquerque EX, Maelicke A. Galantamine is an allosterically potentiating ligand of neuronal nicotinic but not of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;305:1024–36. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.045773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarto-Jackson I, Ramerstorfer J, Ernst M, Sieghart W. Identification of amino acid residues important for assembly of GABA receptor alpha1 and gamma2 subunits. J Neurochem. 2006;96:983–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garcia-Colunga J, Miledi R. Modulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by strychnine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:4113–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.4113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsubayashi H, Alkondon M, Pereira EF, Swanson KL, Albuquerque EX. Strychnine: a potent competitive antagonist of alpha-bungarotoxin-sensitive nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat hippocampal neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;284:904–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schrattenholz A, Godovac-Zimmermann J, Schafer HJ, Albuquerque EX, Maelicke A. Photoaffinity labeling of Torpedo acetylcholine receptor by physostigmine. Eur J Biochem. 1993;216:671–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okonjo KO, Kuhlmann J, Maelicke A. A second pathway of activation of the Torpedo acetylcholine receptor channel. Eur J Biochem. 1991;200:671–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hansen SB, Sulzenbacher G, Huxford T, Marchot P, Taylor P, Bourne Y. Structures of Aplysia AChBP complexes with nicotinic agonists and antagonists reveal distinctive binding interfaces and conformations. Embo J. 2005;24:3635–46. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sine SM, Taylor P. The relationship between agonist occupation and the permeability response of the cholinergic receptor revealed by bound cobra alpha-toxin. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:10144–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miwa JM, Ibanez-Tallon I, Crabtree GW, Sanchez R, Sali A, Role LW, Heintz N. lynx1, an endogenous toxin-like modulator of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the mammalian CNS. Neuron. 1999;23:105–14. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80757-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reeves PJ, Callewaert N, Contreras R, Khorana HG. Structure and function in rhodopsin: high-level expression of rhodopsin with restricted and homogeneous N-glycosylation by a tetracycline-inducible N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase I-negative HEK293S stable mammalian cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13419–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212519299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods in Enzymology. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.CCP4. The CCP4 suite: Programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Navaza J. AMoRe: an automated package for molecular replacement. Acta Crystallogr Sect A. 1994;50:157–163. [Google Scholar]

- 35.McRee D. A visual protein crystallographic software system for X11/XView. J Molecular Graphics. 1992;10:44–46. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of Macromolecular Structures by Maximum-Likelihood Method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Unwin N. Refined structure of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor at 4A resolution. J Mol Biol. 2005;346:967–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brejc K, van Dijk WJ, Klaassen RV, Schuurmans M, van Der Oost J, Smit AB, Sixma TK. Crystal structure of an ACh-binding protein reveals the ligand-binding domain of nicotinic receptors. Nature. 2001;411:269–76. doi: 10.1038/35077011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.