Abstract

Background:

C2 hemisection results in paralysis of the ipsilateral hemidiaphragm. Recent data indicate that an upregulation of the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor 2A subunit following chronic C2 hemisection is associated with spontaneous hemidiaphragmatic recovery following injury. MK-801, an antagonist of the NMDA receptor, upregulates the NR2A subunit in neonatal rats.

Hypothesis:

We hypothesized that administration of MK-801 to adult, acute C2-hemisected rats would result in an increase of NR2A in the spinal cord. Furthermore, we hypothesized that upregulation of NR2A would be associated with recovery of the ipsilateral hemidiaphragm as in the chronic studies.

Design:

To develop a dose-response curve, adult rats were treated with varying doses of MK-801 and their spinal cords harvested and assessed for NR2A as well as AMPA GluR1 and GluR2 subunit protein levels. In the second part of this study, C2-hemisected animals received MK-801. Following treatment, the animals were assessed for recovery of the hemidiaphragm through electromyographic recordings and their spinal cords assessed for NR2A, GluR1, and GluR2.

Results:

Treatment with MK-801 leads to an increase of the NR2A subunit in the spinal cords of adult noninjured rats. There were no changes in the expression of GluR1 and GluR2 in these animals. Administration of MK-801 to C2-hemisected rats resulted in recovery of the ipsilateral hemidiaphragm, an increase of NR2A, and a decrease of GluR2.

Conclusion:

Our findings strengthen the evidence that the NR2A subunit plays a substantial role in mediating recovery of the paralyzed hemidiaphragm following C2 spinal cord hemisection.

Keywords: C2 hemisection, Spinal cord injuries, Motor recovery, Phrenic nucleus, Plasticity, Long-term potentiation, N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA), MK-801, NMDA-receptor antagonist

INTRODUCTION

The descending respiratory drive to the phrenic nucleus arises from medullary respiratory centers (1). A C2 spinal cord hemisection disrupts these pathways and results in paralysis of the ipsilateral hemidiaphragm (2). It has been demonstrated that activation of a spared, latent respiratory pathway crossing over from the contralateral spinal cord to innervate phrenic motor neurons caudal to the C2 hemisection can restore activity to the once-paralyzed hemidiaphragm (3). Activation of the “crossed phrenic pathway” can be induced by severing the phrenic nerve contralateral to the hemisection or after administration of pharmacological agents in an acute model of the C2 hemisection (3–6). Chronically, after C2 hemisection, activation of the crossed phrenic pathway occurs spontaneously without any kind of intervention and restores ipsilateral hemidiaphragmatic function (7).

The mechanisms underlying the spontaneous recovery of hemidiaphragm function are not well understood. However, recent data from our laboratory have indicated that an upregulation of the 2A subunit (NR2A) of the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor may be a possible mediator of spontaneous recovery (7). Furthermore, an upregulation of the GluR1 subunit of the alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionate (AMPA) receptor and down regulation of the GluR2 subunit of the AMPA receptor following C2 hemisection have also been implicated as potential mediators underlying the chronic, spontaneous recovery of the ipsilateral hemidiaphragm following C2 hemisection. An upregulation of NR2A subunit protein occurs at 6 and 12 weeks following C2 hemisection (8). GluR1 is upregulated 6, 12, and 16 weeks post hemisection, and GluR2 is down regulated at 16 weeks post hemisection. These changes correlate with the same time points at which spontaneous recovery occurs in our C2-hemisection model. Consistent with previous work, it was determined that these subunits are indeed present on phrenic motor neurons (10). Furthermore, an upregulation of NR2A subunit mRNA and a down regulation of GluR2 mRNA in ventral horn motor neurons was also correlated with an improvement of hind limb motor function in a chronic model of T8 spinal cord injury (11,12).

The NMDA receptor is a pentameric complex composed of the NR1 and NR2A-D subunits. Each subunit confers distinct physiological and biochemical properties to the NMDA receptor (13–17). Physiologically, the NR2A subunit has been implicated as a necessary component in the induction of the synaptic plasticity known as long-term potentiation (LTP) in the hippocampus (18,19). The upregulation of NR2A in the cited spinal cord injury models may play the same role and mediate synaptic plasticity in spared pathways, inducing LTP, and increasing synaptic efficacy in ventral horn motor neurons, resulting in improved functional motor activity.

The AMPA receptors are the primary glutamatergic receptors in the central nervous system (CNS). Specifically, in the respiratory system, the AMPA receptor is the primary mediator of the descending glutamatergic respiratory drive (20,21). Like the NMDA receptor, the AMPA receptor is composed of differing subunits (GluR1–GluR4), with each one conferring different properties. The GluR1/GluR2 heteromeral AMPA receptor complex is delivered to the synapse on the basis of synaptic activity, in particular, through activation of the NMDA receptor (22). In addition, the GluR2 subunit is the calcium gate of the AMPA receptor, and deletion or down regulation of the subunit has been implicated as a mediator of synaptic plasticity and an enhancer of LTP (23,24). For extensive discussion of both NMDA and AMPA receptors and their subunits, please see the recent review by Mayer (17).

MK-801 or dizocilpine is a noncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonist. In previous studies examining NMDA-mediated excitotoxicity, pretreatment with MK-801 to block NMDA receptors prior to the administration of an excitotoxic dose of NMDA in the neonatal rat resulted in an augmented CNS insult (25). In the same study, it was determined through radio-ligand binding studies that pretreatment with MK-801 resulted in a higher number of NMDA binding sites, resulting in the enhanced insult. Subsequent studies using in situ hybridization have demonstrated that treatment with MK-801 results in a preferential increase of the NR2A subunit in various brain regions of the neonatal rat (26).

The present study was designed to determine whether MK-801 administration in adult rats results in an increased expression of the NR2A subunit at the level of the phrenic nucleus in the spinal cord. Furthermore, since an upregulation of the NR2A subunit has been correlated with chronic spontaneous recovery after spinal cord injury, we predicted that an increase in NR2A would lead toward functional motor recovery of the paralyzed hemidiaphragm in acute, C2-hemisected rats. The AMPA receptor subunits GluR1 and GluR2 were also assessed following these treatments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

MK-801 Administration and Dose-Response Curve

A dose-response study was initiated to determine which dose(s) of MK-801 was/were necessary and sufficient to increase NR2A subunit protein at the level of the phrenic motor nucleus. Noninjured adult female Sprague-Dawley rats (250–350 g) were divided into 5 groups (n = 5 per group) and received either vehicle treatment (saline) or MK-801 treatment at one of the following dosages: 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, or 1.0 mg/kg. Starting dosages were obtained from studies conducted on neonatal rats (25,26). MK-801 was prepared by dissolving the appropriate amount in 1 mL of sterile saline. Animals received vehicle or MK-801 (single intraperitoneal [IP] injection) once per day for 2 consecutive days (Table 1). Two days after the last administration, the animals were sacrificed and the ventral, left quarter of the spinal cord at C3-C6 (level of the phrenic nucleus) was harvested from each animal and Western blot analysis was performed (Table 1). We also examined whether MK-801 treatment led to changes in the AMPA receptor subunits GluR1 and GluR2.

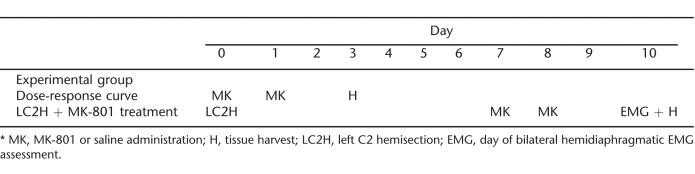

Table 1.

Treatment Schedule for the Dose-Response Curve and Administration of MK-801 to Left C2-Hemisected Animals*

C2 Hemisection and Electromyographic Recordings

Adult female Sprague-Dawley rats (250–350 g) were anesthetized with a ketamine (70 mg/kg) and xylazine (7 mg/kg) solution administered intraperitoneally. Following administration of anesthesia, the animals were prepared for surgery by shaving and cleansing the dorsal neck area with betadine and rubbing alcohol. Following cleansing and sterilization, a dorsal midline incision approximately 4-cm long was made on the neck. The paravertebral muscles were cut and retracted, and a second cervical laminectomy was performed. The dura and arachnoid mater were cut and the spinal cord exposed. A left C2 hemisection caudal to the C2 dorsal root was made with a sharp microblade. The hemisection was made from the spinal cord midline to the most lateral extent. The muscle layers were drawn back together with 3–0 suture and the skin stapled with wound clips.

Immediately after the hemisection, the animals were assessed for functional completeness of the hemisection. Following cleansing as described above, an 8-cm incision was made at the base of the rib cage to expose the abdominal surface of the diaphragm in spontaneously breathing animals. Bipolar electrodes were inserted in the left and right side of the diaphragm to record respiratory diaphragmatic activity. Animals that displayed no activity on the side ipsilateral to the lesion, indicating a functionally complete hemisection, were included in the study. Animals that displayed residual activity ipsilateral to the hemisection were not included in the study. The muscle layers were sutured back together and the skin stapled.

Following these surgical procedures, all animals received saline (10 mL subcutaneously [SC]) and the analgesic buprenorphine (0.1 mg/kg, SC). The animals were placed on a circulating water blanket until they regained consciousness, upon which time they were returned to their cages. Rats were housed individually on a normal day/night schedule and given food and water ad libitum. Rats were monitored each day and 5 to 10 mL of subcutaneous saline was administered if animals appeared dehydrated. All animal care and handling were carried out under strict compliance with the Division of Laboratory Animal Research at Wayne State University.

MK-801 Treatment of Hemisected Animals

Based on the results obtained from the dose-response study (see Results), the hemisected animals were divided into 3 groups: (a) saline-treated (n = 9), (b) 0.125 mg/kg MK-801–treated (n = 6); and (c) 0.5 mg/kg MK-801–treated (n = 11). On days 7 and 8 after the hemisection, the animals received the indicated treatments (Table 1). Two days after the last administration, which was 10 days post hemisection, the animals were anesthetized with chloral hydrate (400 mg/kg IP), and electromyographic (EMG) activity of the diaphragm was again evaluated as described above to determine whether functional recovery of the ipsilateral hemidiaphragm had occurred (Table 1).

Gel Electrophoresis and Western Blot Analysis

Following the assessment of functional recovery by EMG recording in the 3 experimental groups (as described above), the spinal cords were harvested at the level of the phrenic nucleus (C3–C6). The spinal cords were bisected rostra-caudally into left and right sides and the left, injured side of the spinal cord was further dissected by removing the dorsal half. The left ventral quarters of these spinal cords were stored at −80°C until processed for electrophoresis.

Processing involved sonication of the tissues in a modified Glasgow protein extraction buffer that included 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1.0 mmol/L EDTA, 50 mmol/L Tris, 1% NP40, 0.1% Triton X-100, and protease inhibitors. Following sonication, the solutions were centrifuged for 30 minutes at 15,000 rcf (relative centrifugal force). The supernatants were collected and the protein concentration was determined using the Bradford assay (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Protein homogenate (50 μg total) in a 40-μL solution including Laemmli sample buffer was then loaded onto a 7.5% Tris-HCl gel (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and separated. Following separation, the proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane.

The PVDF membranes were washed 3× with a Tris/Tween/saline buffer (TBST), followed by blocking with 8% milk, 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 2% normal goat serum (NGS). Following the blocking step, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C in the primary antibody diluted in a 1% BSA and 1% NGS TBST solution. The primary antibodies used were a mouse monoclonal anti-NR2A (1:2000), and rabbit polyclonal anti-GluR1 (1:400) and anti-GluR2 (1:2000) (all antibodies were purchased from Chemicon, Temecula, CA). Membranes were washed extensively and then incubated in a peroxidase conjugated goat antimouse or goat antirabbit secondary antibody diluted 1:2500 and 1:5000, respectively, in a 1% BSA and 1% NGS TBST solution for 2 hours at room temperature. The membranes were again washed extensively with TBST and incubated in an enhanced chemiluminescent peroxidase substrate (Chemicon) for 5 minutes and then apposed to film and developed.

The films were scanned with the Image Scanner II, and bands corresponding to the subunits were quantified with the ImageQuant TL program (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). The area and density were measured, and the band intensity derived. A standard rat cortical tissue was run with each gel to standardize measurements between individual gels, since the cortex contains high levels of NR2A, GluR1, and GluR2 subunit protein.

Statistical Analysis

SigmaStat (Point Richmond, CA) was used to determine statistical significance. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used along with Bonferonni's method to compare experimental groups with control animals., Values are expressed as means ± the standard error. A P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Immunocytochemistry

Following the EMG recordings, a portion of the animals treated with saline and 0.5 mg/kg MK-801 (n = 3 per treatment) were perfused with saline (50 mL) followed by a 2.5% glutaraldehyde/1% paraformaldehyde solution in 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer (PB) (250 mL). The spinal cords were harvested and postfixed for 2 hours before cryoprotection in 30% sucrose in 0.1 mol/L PB. Following cryoprotection, the C3–C6 levels of the spinal cord, which contain the phrenic nucleus, were dissected and a pinhole was made on the right side to distinguish between the left and right spinal cord. The spinal cord tissues were embedded in OCT compound (Tissue Tek, Torrance, CA), sectioned transversely on a cryostat at a 50 μm thickness and stored in PBS at 4°C.

For the immunocytochemistry studies, tissue sections from all different groups were processed at the same time. Tissue sections were washed first with a 1% sodium borohydrate solution, followed by PBS washing 3 times. Endogenous peroxidase was quenched with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide, and sections were blocked and permeabilized with a 10% NGS/0.3% Triton X-100 0.1 mol/L PBS solution for 30 minutes. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4°C in rabbit polyclonal antibodies directed against NR2A (1:1000), GluR1 (1:200–1:700), and GluR2 (1:500) diluted in 1% NGS/0.3% Triton X-100 0.1 mol/L PBS solution. Following incubation and extensive washing with PBS, the sections were incubated in biotinylated goat antirabbit antibody (1:200) diluted in 0.3% Triton X-100 in 1% NGS for 2 hours at room temperature and then processed according to the Vector Laboratory ABC method (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Immunoreactive areas of the sections were developed and visualized with a DAB substrate/hydrogen peroxide solution.

Sections were viewed using a Nikon bright-field microscopy setup. Digital photographs were taken with a SPOT digital camera and imaging software (Diagnostic Instruments Inc., Sterling Heights, MI).

RESULTS

NMDA and AMPA Subunit Expression in Adult, Noninjured Rats Treated With MK-801 at the Level of the Phrenic Nucleus

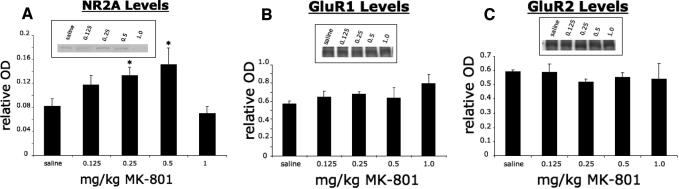

There was an upregulation of NR2A subunit protein in the left ventral C3–C6 spinal cord in noninjured adult female rats treated with MK-801, as revealed by Western blot analysis. Treatment with 0.25 or 0.5 mg/kg MK-801 resulted in a significant increase of NR2A subunit, as determined through Western blot analysis, whereas treatment with 0.125 or 1.0 mg/kg MK-801 resulted in no significant increase (Figure 1A). The expression of the AMPA receptor subunits GluR1 and GluR2 was not affected by MK-801 treatment at any dosage in non-injured rats (Figures 1, B and C).

Figure 1. Increase in NR2A after treatment with 0.25 or 0.5 mg/kg MK-801 as revealed by Western blot analysis. (A) All optical density values (OD) corresponding to NR2A levels are relative to a standard cortical sample run alongside the samples. After treatment with 0.25 or 0.5 mg/kg MK-801 for 2 consecutive days, the left spinal cord of noninjured animals had a significant increase of NR2A compared to saline-treated control animals (A). There was no significant change in animals treated with 0.125 or 1.0 mg/kg MK-801 (A). No significant change of GluR1 (B) or GluR2 (C) after any dose of MK-801. All values are relative to a standard cortical sample run alongside the samples. After treatment with 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, or 1.0 mg/kg for 2 consecutive days, there were no changes in the levels of GluR1 or GluR2 in the left spinal cord of adult noninjured animals compared to saline-treated controls as revealed by Western blot analysis (B and C). * indicates significance with P < 0.05. Inserts show a representative Western blot.

NMDA and AMPA Subunit Expression in Adult, C2 Hemisected Rats 10 Days Following Hemisection and Treatment With MK-801

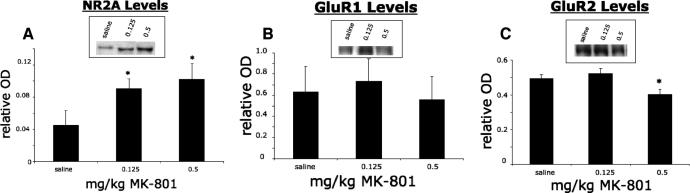

Levels of NR2A subunit protein of left C2-hemisected animals treated with MK-801 or saline were assessed through Western blot analysis of the ventral half of the left C3–C6 spinal cord. Treatment with either 0.125 or 0.5 mg/kg MK-801 for 2 consecutive days starting 1 week after hemisection resulted in a significant increase of NR2A compared to saline-treated animals (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Significant increase of NR2A following C2 hemisection and treatment with MK-801 as revealed by Western blot analysis (A). All values are relative to a standard cortical sample run alongside the samples. After 2 days of consecutive treatment with either 0.125 or 0.5 mg/kg MK-801, there was a significant increase of NR2A in the left spinal cord of C2-hemisected animals compared to saline-treated controls (A). No significant change of GluR1 (B) and down regulation of GluR2 (C) following C2 hemisection and treatment with MK-801 as revealed by Western blot analysis. All values are relative to a standard cortical sample run alongside the samples. After 2 days of consecutive treatment with either 0.125 or 0.5 mg/kg MK-801, there was no significant change in the levels of GluR1 in C2-hemisected rats compared to saline-treated animals (B). However, treatment with 0.5 mg/kg MK-801 resulted in a significant reduction of GluR2 levels compared to saline-treated animals (C). * indicates significance with P < 0.05. Representative Western blots shown in the inserts.

Western blot analysis of the ventral half of the left C3–C6 spinal cord revealed that treatment of left C2-hemisected animals with either 0.125 or 0.5 mg/kg MK-801 resulted in no change of the protein levels of the AMPA receptor subunit GluR1 compared to saline-treated hemisected animals (Figure 2B). However, administration of 0.5 mg/kg MK-801 to hemisected rats resulted in a significant decrease of the GluR2 subunit. Hemisected rats that received the 0.125 mg/kg MK-801 dosage did not have a significant change in the expression of GluR2 (Figure 2C). Ten days following C2 hemisection and treatment with vehicle, there were no significant changes of NR2A, GluR1, and GluR2 compared to noninjured animals.

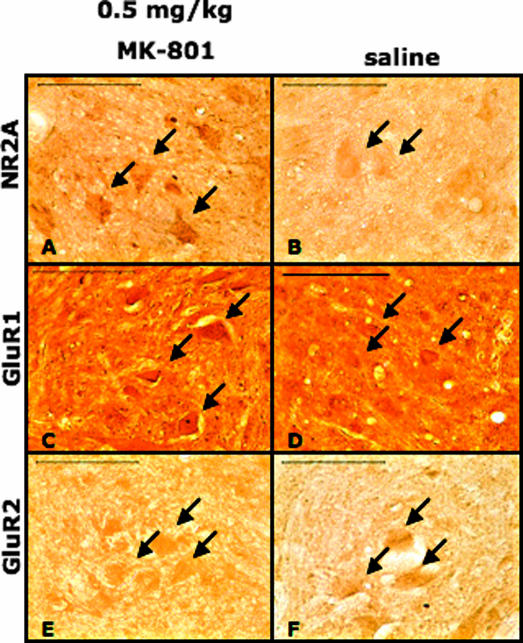

NR2A and AMPA Receptor Subunit Expression on C3–C6 Ventral Horn Motor Neurons

NR2A, GluR1, and GluR2 were localized in ipsilateral C3–C6 ventral horn motor neurons in saline and 0.5 mg/kg MK-801–treated left C2-hemisected rats through immunocytochemistry. The immunocytochemical analysis qualitatively supported the findings of the Western blot analysis.

Treatment of C2-hemisected animals with 0.5 mg/kg MK-801 resulted in an increase of NR2A immunoreactivity on C3–C6 ventral horn motor neurons compared to saline-treated rats (Figures 3A and B). It appeared that there was a similar intensity of GluR1 immunoreactivity on ventral horn motor neurons between saline and 0.5 mg/kg MK-801–treated animals, indicating no difference in the levels of GluR1 (Figures 3C and D). There was a slight decrease, however, of GluR2 immunoreactivity on ventral horn motor neurons when C2-hemisected animals were treated with 0.5 mg/kg MK-801 compared to control (Figures 3E and F).

Figure 3. Light micrographs showing that treatment of C2-hemisected rats with 0.5 mg/kg MK-801 induces an upregulation of NR2A, no change in GluR1, and a down regulation of GluR2 in C3–C6 ventral horn motor neurons. A, C, and E are C2-hemisected rats treated with 0.5 mg/kg MK-801. B, D, and F are C2-hemisected rats treated with saline. NR2A (A and B), GluR1 (C and D), and GluR2 (E and F) subunits are localized to motor neurons (arrows). Scale bars = 100 μm.

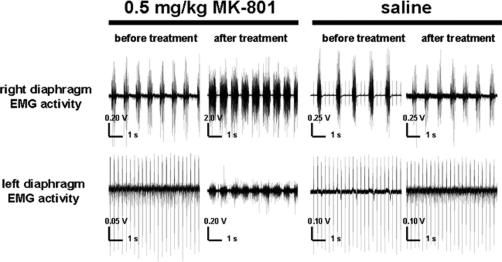

EMG Activity in the Diaphragms of C2-Hemisected Rats Treated With MK-801

Following left C2 hemisection, there was an absence of respiratory activity in the ipsilateral hemidiaphragm, observed through bilateral EMG recordings (Figure 4). Treatment with 0.5 mg/kg of MK-801 for 2 days starting 7 days after hemisection resulted in a return of hemidiaphragm motor activity in 8 of the 11 animals (Figure 4). For animals treated with 0.125 mg/kg MK-801, recovery was present in 1 out of the 6 animals treated (data not shown). For both groups, recovery was present 2 days after the last administration of drug or 10 days after the C2 hemisections. The recovered EMG activity of the once-paralyzed hemidiaphragm coincided with respiratory-related activity of the noninjured side (Figure 4). Treatment with vehicle control at the same time points resulted in no return of hemidiaphragm motor activity in any animal (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Electromyograms from both the left and right sides of the hemidiaphragm of a saline-treated and the same 0.5 mg/kg MK-801–treated left C2-hemisected rat before and after drug treatment. In both saline- and MK-801–treated rats, there was an absence of EMG activity on the left hemidiaphragm following C2 hemisection and before treatment (first and third pair of traces). Following saline treatment for 2 consecutive days starting 7 days after injury, there was no return of diaphragmatic activity as observed through EMG activity (fourth pair of traces). Following 0.5 mg/kg MK-801 treatment for 2 consecutive days starting 1 week after injury, there was a return of left hemidiaphragmatic activity that was rhythmic and synchronized to the right hemidiaphragm as revealed through bilateral EMG recordings (second pair of traces). Each trace is 7 seconds long. Note difference in scale bars.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrates that administration of MK-801 to noninjured adult rats induces an upregulation of the NR2A subunit in the C3–C6 spinal cord. No changes were observed in the expression of the AMPA receptor subunits GluR1 and GluR2 in noninjured animals. Furthermore, this study also shows that administration of MK-801 to C2-hemisected rats results in an upregulation of the NR2A subunit at the C3–C6 spinal cord and a return of functional hemidiaphragmatic recovery. In addition, MK-801 treatment of C2-hemi-sected animals leads to a decrease in the AMPA receptor subunit GluR2, whose down regulation has been implicated as a mediator of synaptic plasticity and long-term potentiation enhancement.

Antagonism of the NMDA Receptor Leads to Upregulation of NR2A Subunit Protein and Enhanced LTP

Previous work has demonstrated that antagonism of the NMDA receptor results in alterations of NMDA receptor subunits. As stated previously, administration of MK-801 to neonatal rats resulted in an increase of NMDA binding sites (25). Later studies from the same group showed that there was a preferential increase of NR2A mRNA after MK-801 administration in the cortex, striatum, and hippocampus (26). In other studies, exogenous treatment with phencyclidine (PCP), another noncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonist that acts at the same site as MK-801, resulted in an increase of the NR2A subunit on corticostriatal slice cultures (27). However, there is no consensus on the effects of NMDA receptor antagonism on NMDA receptor subunit regulation, and different results have been reported (28,29). The differences may be due to the different anatomical regions investigated, antagonists used, dosages, and durations of drug administration in these different studies. However, in this report, we demonstrate through Western blot analysis that administration of MK-801 results in an increase of the NR2A protein after 2 consecutive days of 0.25 or 0.5 mg/kg treatment in noninjured rats. In spinal cord–injured rats, MK-801 also induced an upregulation of NR2A subunit protein at dosages of 0.125 and 0.5 mg/kg.

It has been recently observed that in addition to inducing changes of NMDA receptor subunits, treatment with MK-801 can enhance LTP. In a study by Buck and colleagues, treatment of adult rats with MK-801 led to an enhancement of LTP at the CA1-subiculum synapse (30). It has been demonstrated that the NR2A subunit is the primary mediator of LTP (18). Therefore, it is plausible that upregulation of NR2A through MK-801 treatment mediates a form of LTP in our C2-hemisection model.

NR2A- and GluR2-Mediated Plasticity

Data from previous work have shown that following chronic C2 hemisection, there is an increase of NR2A subunit protein at the level of the phrenic nucleus at 6 and 12 weeks (7). These time points correlate with the onset and full establishment of spontaneous recovery of the ipsilateral hemidiaphragm (9). Also, at 16 weeks post injury, there is a significant reduction of the GluR2 subunit (8). The findings of these studies are consistent with other work that has investigated changes in NMDA and AMPA receptor subunits. Specifically, in a T8 model of spinal cord injury, an increase in NR2A and a decrease of GluR2 was also reported and correlated with improved hind limb function (11,12).

A distinctive feature of the NR2A and GluR2 subunits is the capacity to mediate synaptic plasticity. In a study by Liu et al, induction of LTP in hippocampal slices was blocked after administration of NR2A-specific antagonists, suggesting an essential role for NR2A in LTP induction (18). Other studies have confirmed these findings (19). The GluR2 subunit is the calcium gate of the AMPA receptor. It has been demonstrated that reductions of the GluR2 subunit lead to increases of Ca++ influx and an enhanced expression of LTP (24,31–33). Therefore, it is plausible that the above changes in glutamate receptor subunits could also lead to the induction of the changes associated with synaptic strengthening in ventral horn motor neurons after chronic experimental spinal cord injury and enhancement of LTP-like mechanisms. The resulting increase in synaptic strength and efficacy in turn would lead to improvement in hind limb function, or in our model, a return of hemidiaphragmatic motor activity, through strengthening of the crossed phrenic synapse.

However, prior to this study, there has been no attempt to selectively upregulate the NR2A subunit or down regulate the GluR2 subunit in a spinal cord injury model to induce or improve functional recovery. One way of achieving this is through administration of NMDA receptor antagonists. In this study, we show that an upregulation of the NR2A subunit can be pharmacologically induced with MK-801 in both noninjured rats and C2-hemisected rats, resulting in functional recovery of the ipsilateral hemidiaphragm. It was also observed that following treatment of C2-hemisected rats with a high dosage of MK-801, there was a down regulation of GluR2, albeit small. The reduction of GluR2 following C2 hemisection and treatment with MK-801 may be induced by hemidiaphragmatic recovery. This is possible because GluR2 protein levels did not change at any dosage of MK-801 in noninjured animals, and saline treatment of C2-hemisected animals led to no change in GluR2 expression. Furthermore, GluR2 was only down regulated at the higher dosage of MK-801 in C2-hemisected rats, where functional recovery was significant. Again, the reduction was quite small and its effect on restoration of respiratory activity may be minimal.

There were no recorded differences in the level of GluR1 proteins in the present study. Previous studies investigating chronic C2 hemisection revealed that there is an upregulation of the GluR1 subunit receptor at time points when spontaneous recovery occurs (6–16 wk post hemisection). The contradiction in results may be due to insufficient time for the upregulation of GluR1 to occur in the present study, or possibly, existing GluR1 subunits are sufficient for the recovery observed in the MK-801–induced recovery model.

Treatment with Glutamate Receptor Antagonists: Neuroprotection and Neurotrophic Factors

There is ample evidence that glutamate concentrations following traumatic brain injury, and specifically spinal cord injury, reach toxic levels (34–36). The rise in glutamate concentration is a cause of much of the secondary damage and neuronal death after the injury itself. Both neurons and oligodendrocytes are vulnerable to excitotoxicity (35,37).

Various treatment regimes have been utilized to minimize the damage caused by the rise in glutamate following trauma. Primary among them is the antagonism of both AMPA and NMDA glutamate receptors; both have been shown to mediate cell death (38). In a spinal cord injury study by Wrathall et al, administration of AMPA and kainite glutamate receptor antagonists resulted in a dose-dependent reduction of tissue loss and improved functional recovery (39). Antagonism of the NMDA receptor with MK-801 following traumatic brain injury resulted in a decrease of neuronal damage (40). Specifically, in models of spinal cord injury, an improvement in functional recovery and cell survival occurs after administration of MK-801 (41,42). It can be concluded that administration of glutamate receptor antagonists, and specifically, the NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801, has been shown to improve functional recovery and cell survival through neuroprotective mechanisms.

Aside from its neuroprotective effects, another aspect of MK-801 that may aid in the survival of CNS cells after injury is its effect on neurotrophic factors, specifically brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). It has been shown that administration of MK-801 to adult rats results in a dose-dependent upregulation of BDNF mRNA, suggesting a link between NMDA receptor activation, antagonism, and BDNF synthesis (43,44). This is noteworthy because BDNF has also been implicated as a mediator of synaptic plasticity, in particular increasing synaptic activity and transmission (45–47).

In spinal cord injury models, BDNF administration after SCI results in axonal regeneration and stimulated hind limb stepping and locomotor activity (48–50). Within the respiratory system, BDNF plays an essential role in the induction of phrenic long-term facilitation (LTF), a type of long-term plasticity (51). Just recently, the induction of phrenic LTF has also been shown to be dependent on NMDA receptor activation—strengthening the link between BDNF, NMDA receptor activation, and phrenic output (52). It would be interesting to determine whether there is a change in BDNF levels after administration of MK-801 in C2-hemisected animals. It is conceivable that the combined effect of increasing NR2A, decreasing GluR2, and increasing BDNF levels may lead to the activation of phrenic motor neurons and the return of hemidiaphragmatic motor function after cervical spinal cord hemisection. Such a study is presently underway in our laboratory.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, this report shows that MK-801 induced an upregulation of the 2A subunit of the NMDA receptor and a down regulation of the GluR2 AMPA subunit, which is associated with a return of hemidiaphragmatic activity after C2 hemisection. Furthermore, the changes in NR2A and GluR2 receptor subunits in this acute model closely parallel glutamate receptor changes associated with spontaneous recovery observed after chronic C2 hemisection. Manipulation of the glutamate receptor subunits in humans with spinal cord injury may be a potential therapy that can lead to an improvement in motor function.

REFERENCES

- Dobbins EG, Feldman JL. Brainstem network controlling descending drive to phrenic motoneurons in rat. J Comp Neurol. 1994;347:64–86. doi: 10.1002/cne.903470106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshgarian HG, Guth L. Demonstration of functionally ineffective synapses in the guinea pig spinal cord. Exp Neurol. 1977;57:613–621. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(77)90093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter WT. The path of the respiratory impulse from the bulb to the phrenic nuclei. J Physiol. 1895;17:455–485. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1895.sp000553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nantwi KD, El Bohy A, Goshgarian HG. Actions of systemic theophylline on hemidiaphragmatic recovery in rats following cervical spinal cord hemisection. Exp Neurol. 1996;140:53–59. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1996.0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou SY, Goshgarian HG. Effects of serotonin on crossed phrenic nerve activity in cervical spinal cord hemisection in cervical spinal cord hemisected rats. Exp Neurol. 1999;160:446–453. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou SY, Goshgarian HG. 5-Hydroxytryptophan-induced respiratory recovery after cervical spinal cord hemisection in rats. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89:1528–1536. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.4.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alilain WJ, Goshgarian HG. N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor 2A subunit upregulation following C2 spinal hemisection in adult rats. Abstract #11. J Spinal Cord Med. 2005;28(4):366. [Google Scholar]

- Alilain WJ, Goshgarian HG. AMPA receptor subunit regulation following C2 spinal cord hemisection in adult rats. Society for Neuroscience Annual Meeting in Washington, DC. 2005: Program No. 784.15.

- Nantwi KD, El Bohy A, Schrimsher GW, Reier PJ, Goshgarian HG. Spontaneous functional recovery in paralyzed hemidiaphragm following upper cervical spinal cord injury in adult rats. Neurorehabil Repair. 1999;13:225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson D, Ellenber H. Distribution of N-methyl-d-aspartate and non-N-methyl-d-aspartate glutamate receptor subunits on respiratory motor and premotor neurons in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1997;389:94–116. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19971208)389:1<94::aid-cne7>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman SD, Wolfe BB, Yasuda RP, Wrathall JR. Alterations in AMPA receptor subunit expression after experimental spinal cord contusion injury. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5711–5720. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-05711.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman SD, Wolfe BB, Yasuda RP, Wrathall JR. Changes in NMDA receptor subunit expression in response to contusive spinal cord injury. J Neurochem. 2000;75:174–184. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monyer H, Sprengel R, Schoepfer R, et al. Heteromeric NMDA receptors: molecular and functional distinction of subtypes. Science. 1992;256:1217–1221. doi: 10.1126/science.256.5060.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii T, Moriyoshi K, Sugihara H, et al. Molecular characterization of the family of the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor subunits. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:2836–2843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monyer H, Burnashev N, Laurie DJ, Sakmann B, Seeburg PH. Developmental and regional expression in the rat brain and functional properties of four NMDA receptors. Neuron. 1994;12:529–540. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupp JJ, Vissel B, Heinemann SF, Westbrook GL. N-terminal domains in the NR2 subunit control desensitization of NMDA receptors. Neuron. 1998;20:317–327. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80459-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer ML. Glutamate receptors at atomic resolution. Nature. 2006;440:456–462. doi: 10.1038/nature04709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Wong TP, Pozza MF, et al. Role of NMDA receptor subtypes in governing the direction of hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Science. 2004;304:1021–1024. doi: 10.1126/science.1096615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey PV, Johnson BE, Moult PR, et al. Differential roles of NR2A and NR2B-containing NMDA receptors in cortical long-term potentiation and long-term depression. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7821–7828. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1697-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrimmon DR, Speck DF, Feldman JL. Involvement of excitatory amino acids in neurotransmission of inspiratory drive to spinal respiratory motoneurons. J Neurosci. 1989;9:1910–1921. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-06-01910.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Feldman JL, Smith JC. Excitatory amino acid–mediated transmission of inspiratory drive to phrenic motoneurons. J Neurophysiol. 1990;64:423–436. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.64.2.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteban JA. AMPA receptor trafficking: a roadmap for synaptic plasticity. Mol Interv. 2003;3:375–385. doi: 10.1124/mi.3.7.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett MV, Pellegrini-Giampietro DE, Gorter JA, Aronica E, Connor JA, Zukin RS. The GluR2 hypothesis: Ca(++)-permeable AMPA receptors in delayed neurodegeneration. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1996;61:373–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Z, Agopyan N, Miu P, et al. Enhanced LTP in mice deficient in the AMPA receptor GluR2. Neuron. 1996;17:945–956. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80225-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JW, Silverstein FS, Johnston MV. MK-801 pretreatment enhances N-methyl-d-aspartate- and quis-qualate-mediated neurotoxicity in perinatal rats. Neuroscience. 1990;36:589–600. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90002-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MA, Kinsman SL, Johnston MV. Expression of NMDA receptor subunit mRNA after MK-801 treatment in neonatal rats. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1998;109:211–220. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Fridley J, Johnson K. The role of NMDA receptor upregulation in phencyclidine-induced cortical apoptosis in organotypic culture. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;69:1373–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden AM, Vasanen J, Storvik M, et al. Uncompetitive antagonists of the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors alter the mRNA expression of proteins associated with the NMDA receptor complex. Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;88:98–105. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2001.d01-89.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl JS, Keifer J. Glutamate receptor subunits are altered in forebrain and cerebellum in rats chronically exposed to the NMDA receptor antagonist phencyclidine. Neuropsy-chopharmacology. 2004;29:2065–2073. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck N, Cali S, Behr J. Enhancement of long-term potentiation at CA1-subiculum synapses in MK-801-treated rats. Neurosci Lett. 2006;392:5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu JG, Albuquerque C, Lee CJ, MacDermott AB. Synaptic strengthening through activation of Ca2+-permeable AM-PA receptors. Nature. 1996;381:793–796. doi: 10.1038/381793a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainen ZF, Jia Z, Roder J, Malinow R. Use-dependent AMPA receptor block in mice lacking GluR2 suggests postsynaptic site for LTP expression. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:579–586. doi: 10.1038/2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Y, Zhang Y, Jia Z. Synaptic transmission and plasticity in the absence of AMPA glutamate receptor GluR2 and GluR3. Neuron. 2003;39:163–176. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00368-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panter SS, Yum SW, Faden AI. Alteration in extracellular amino acids after traumatic spinal cord injury. Ann Neurol. 1990;27:96–99. doi: 10.1002/ana.410270115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Thangnipon W, McAdoo DJ. Excitatory amino acids rise to toxic levels upon impact injury to the rat spinal cord. Brain Res. 1991;547:344–348. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90984-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Xu GY, Pan E, McAdoo DJ. Neurotoxicity of glutamate at the concentration released upon spinal cord injury. Neuroscience. 1999;93:1383–1389. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00278-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu GY, Hughes MG, Ye Z, Hulsebosch CE, McAdoo DJ. Concentrations of glutamate released following spinal cord injury kill oligodendrocytes in the spinal cord. Exp Neurol. 2004;187:329–336. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass TF, Reeves B, Sharp FR. The impact of excitotoxic blockade on the evolution of injury following combined mechanical and hypoxic insults in primary rat neuronal culture. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;17:378–384. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrathall JR, Choiniere D, Teng YD. Dose-dependent reduction of tissue loss and functional impairment after spinal cord trauma with the AMPA/kainate antagonist NBQX. J Neurosci. 1994;14:6598–6607. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-06598.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goda M, Isono M, Fujiki M, Kobayashi H. Both MK801 and NBQX reduce the neuronal damage after impact-acceleration brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2002;19:1445–1456. doi: 10.1089/089771502320914679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faden AI, Lemke M, Simon RP, Noble LJ. N-methyl-d-aspartate antagonist MK801 improves outcome following traumatic spinal cord injury in rats: behavioral, anatomic, and neurochemical studies. J Neurotrauma. 1988;5:33–45. doi: 10.1089/neu.1988.5.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Pinilla F, Tram H, Cotman CW, Nieto-Sampedro M. Neuroprotective effect of MK-801 and U-50488H after contusive spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 1989;104:118–124. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(89)80004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castren E, da Penha Berzaghi M, Lindholm D, Thoenen H. Differential effects of MK-801 on brain-derived neuro-trophic factor mRNA levels in different regions of the rat brain. Exp Neurol. 1993;122:244–252. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1993.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes P, Dragunow M, Beilharz E, Lawlor P, Gluckman P. MK-801 induces immediate-early gene proteins and BDNF mRNA in rat cerebrocortical neurones. Neuroreport. 1993;4:183–186. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199302000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Causing CG, Gloster A, Aloyz R, et al. Synaptic innervation density is regulated by neuron-derived BDNF. Neuron. 1997;18:257–267. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80266-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kafitz KW, Rose CR, Thoenen H, Konnerth A. Neurotrophin-evoked rapid excitation through TrkB receptors. Nature. 1999;401:918–921. doi: 10.1038/44847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu B, Figurov A. Role of neurotrophins in synapse development and plasticity. Rev Neurosci. 1997;8:1–12. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.1997.8.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bregman BS, McAtee M, Dai HN, Kuhn PL. Neurotrophic factors increase axonal growth after spinal cord injury and transplantation in the adult rat. Exp Neurol. 1997;148:475–494. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakeman LB, Wei P, Guan Z, Stokes BT. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor stimulates hindlimb stepping and sprouting of cholinergic fibers after spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 1998;154:170–184. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.6924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankeny DP, McTigue DM, Guan Z, et al. Pegylated brain-derived neurotrophic factor shows improved distribution into the spinal cord and stimulates locomotor activity and morphological changes after injury. Exp Neurol. 2001;170:85–100. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Herman TL, Fuller DD, Bavis RW, et al. BDNF is necessary and sufficient for spinal respiratory plasticity following intermittent hypoxia. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:48–55. doi: 10.1038/nn1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire M, Zhang Y, White DP, Ling L. Phrenic long-term facilitation requires NMDA receptors in the phrenic motonucleus in rats. J Physiol. 2005;567:599–611. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.087650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]