Abstract

Most cases of hearing loss are caused by the death or dysfunction of one of the many cochlear cell types. We examined whether cells from a neural stem cell line could replace cochlear cell types lost after exposure to intense noise. For this purpose, we transplanted a clonal stem cell line into the scala tympani of sound damaged mice and guinea pigs. Utilizing morphological, protein expression and genetic criteria, stem cells were found with characteristics of both neural tissues (satellite, spiral ganglion and Schwann cells) and cells of the organ of Corti (hair cells, supporting cells). Additionally, noise-exposed, stem cell-injected animals exhibited a small but significant increase in the number of satellite cells and Type I spiral ganglion neurons compared to non-injected noise-exposed animals. These results indicate that cells of this neural stem cell line migrate from the scala tympani to Rosenthal's canal and the organ of Corti. Moreover, it suggests that cells of this neural stem cell line may derive some information needed from the microenvironment of the cochlea to differentiate into replacement cells in the cochlea.

Keywords: stem cell, hearing loss, spiral ganglion, hair cell

Introduction

The mammalian cochlea is a highly structured organ consisting of a wide variety of cell types. Although hearing loss is mainly attributed to the loss of hair cells, the sensory transducers of the cochlea, hearing impairment also results from dysfunction from many different cochlear cell types. For instance, the primary inherited form of deafness in humans is attributed to a mutation of the connexin 26 gene, which is a cytoplasmic gap junction protein located in a variety of cochlear supporting cells (D'Andrea et al., 2002). Diseases of the auditory nerve such as auditory neuropathy (Trautwein et al., 2000) and acoustic Schwannoma (Glastonbury et al., 2002), which involve the degeneration of auditory neurons and glia, respectively, also result in hearing loss.

A biological approach to the amelioration of disease, which involves the replacement of damaged tissue using biological tools, holds great promise when applied as a means of treating hearing loss (Holley, 2002; Kanzaki et al., 2002). While hair cell regeneration has been shown to repair the damaged cochleas of birds (Corwin et al., 1988; Ryals et al., 1988) and a low level of hair cell genesis continues into adulthood in mammalian vestibular systems (Rubel et al., 1995; Warchol et al., 1993), the mature mammalian cochlea has not exhibited any inherent ability to regenerate after trauma. However, injection of viral particles engineered to deliver the transcription factor Math1 into the cochlea has resulted in the production of new cochlear hair cells (Izumikawa et al., 2005; Kawamoto et al., 2003). Another method of cellular replacement is the therapeutic application of exogenous cells that are capable of developing into cochlear cell types. The development of multipotent cell lines derived from stem cells represents a practical source of exogenous cells for the replacement of damaged or ablated cochlear cells (Parker et al., 2004).

Several murine and human stem cell lines have proven to be useful tools for cellular replacement. Notably, the v-myc immortalized murine clonal 17.2 neural stem cell (cNSC) line (Snyder et al., 1992), which is derived from the fetal cerebellum, has been used successfully in several cellular replacement experiments involving the brain and spinal cord. Transplanted cNSCs have been shown to migrate to the site of a brain lesion and differentiate into native cell types, such as oligodendrocytes (Yandava et al., 1999), microglia, astrocytes, cortical neurons (Snyder et al., 1997), and spinal cord glia and neurons (Himes et al., 2001). These results indicate that cNSCs are capable of both replacement of damaged neural tissue and functional recovery after injury (Teng et al., 2002). Moreover, these cNSCs express several markers that are expressed in cochlear tissues, such as connexin 26 and the hair cell marker myosin 7a (Mi et al., 2005; Parker et al., 2005). Therefore, they may be an appropriate tool for cellular replacement within the cochlea.

In this study, we investigated whether transplanted cNSCs could migrate from the scala tympani into different areas of the cochlea and possibly develop characteristics of native neuronal and organ of Corti cell types. To test this, we injected cNSCs into the scala tympani of sound-damaged mice and guinea pigs and allowed the animals to recover for up to six weeks. In both animal models, some of the cNSCs appeared to have migrated throughout the cochlea and demonstrated morphological, protein and genetic characteristics of neural cochlear tissue (e.g. spiral ganglion neurons, satellite cells, Schwann cells) and cells of the organ of Corti ( pillar cells, supporting cells, hair cells).

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

A frozen stock of passage 4 c17.2 cNSCs was provided by one of us (E.Y. Snyder) as previously described (Snyder et al., 1992). The c17.2 neural stem cell line was derived from male murine fetal cerebellar cells that were immortalized with the v-myc proto-oncogene and exhibits constitutive expression of the lacZ gene product E. coli β-galactosidase, which enables the transplanted cNSCs to be identified histochemically using anti-β-galactosidase antibodies (Snyder et al., 1992). The frozen stock was thawed and grown to confluence for four days on 100 mm Corning culture dishes (Fisher Scientific Ltd., Ontario, Canada) at 37°C ( 5% CO2) in media containing Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 5% horse serum (HS), 2mM glutamine, and 1% Antibiotic-Antimycotic (all from Invitrogen (Gibco), Carlsbad, California). This confluent plate was split 1:4, cells were again expanded to confluence and the resulting plates were frozen at −80 °C 1:4 in the above media, supplemented with 20% FBS and 15% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). After two weeks, this stock of c17 NSCs was transferred to liquid nitrogen for long-term storage. All of the cells used in these experiments were derived from this frozen stock. Cells were cultured as undifferentiated cells in the above media for 3−4 days or until 90% confluent. Differentiating conditions were obtained by culturing the cNSCs in the above media, supplemented with 0.5 mM mitomycin c (Sigma, St. Lois, Missouri), which inhibits mitotic spindle formation, for 10 days. For some transplantation experiments, cNSCs were cultured in the above media, supplemented with10 μM bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU; Sigma) for 72 hrs prior to transplantation. It should be noted that since streptomycin was used in these culture conditions, any cells that may be sensitive to this antibiotic would be eliminated when culturing these cells. Cochlear progenitor OC-2 cell lines (gift from Mathew Holley, University of Sheffield, UK), derived from the developing otocyst of the immortomouse, were cultured in proliferating conditions at 33°C in the above media, supplemented with 50U/ml γ-interferon (Sigma) as described (Rivolta et al., 1998). Human neonatal dermal fibrocytes (Cambrex, East Rutherford, New Jersey) were cultured at 37°C in FGM-2 Bullet kit media (Cambrex) as per instruction.

Sound-damage and In Vivo Transplantation

Murine model

Noise damage was performed as previously described (Wang et al., 2002). Four groups of four adult (6-week-old) male FVB mice (Jackson Laboratories) were secured in a wire cage suspended from the ceiling of an acoustic chamber and subjected to two hrs of an 8−16 kHz band of noise presented at 105 dB SPL. Mice were allowed to recover for 48 hrs prior to implantation. Undifferentiated c17.2 cell cultures were trypsinized during their log growth phase, washed in the above serum containing media, pelleted by centrifugation (5 min at 800g), resuspended at 40,000 cells/ μl in Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS; Gibco) and stored in ice until use (within 1 hour). Mice were anesthetized by IP injection of Ketamine (40−60mg/kg)/Xylazine (Xylazine 3−5mg/kg). The auditory bulla was exposed using a high temperature loop tip cauterizer (Aaron Medical Industries, St. Petersburg, Florida). A small piece of adipose tissue or muscle was collected and placed in iced HBSS during access to the bulla. Once the bulla was exposed, a 2 or 10 μl Hamilton syringe was advanced (Kite Manipulator, World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, Florida) into the round window of the cochlea. Cells were then withdrawn from the iced test tubes into a heat sterilized Hamilton Gastight syringe (Fischer Scientific, Suwanee, Georgia). Cells remained in the syringe at room temperature for approximately 10 minutes prior to injection. Control animals were injected with an equivalent volume of vehicle. Next, the gap between the cochlear wall and needle (custom 28, 32 or 33 gauge needle, Hamilton, Reno, Nevada) was sealed by insertion of the collected tissue. Control animals received HBSS injections. The total volume injected ranged from 0.15 μl-2.0 μl over a 10 min injection. The needle was withdrawn 2 minutes after injection and the wound was sutured using 5−0 Chromic Gut biodegradable suture (Ethicon, Somerville, New Jersey). Eight animals died within the first two weeks after surgery. The remaining 8 mice were divided into control and injected groups, where four animals (1 control and three stem cell injected) were anesthetized and decapitated after 2 weeks, and another four animals (1 control and three stem cell-injected) were similarly sacrificed 4 weeks after surgery. For each time point, cochleas were removed, placed in 4% paraformaldehyde 2 hrs, incubated in 4% ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA, Sigma) for three days at 4 °C, subjected to increased concentrations of sucrose washes, embedded in Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) compound (Ted Pella Inc, Redding, Ca), frozen in liquid nitrogen, cryosectioned in 16 μM slices and stored at 4 °C until use.

Guinea pig model

Eight male and seven female one month old guinea pigs (Mid South Distributors, Slidell, Louisiana) were used in this study and all were subjected to daily cyclosporine (Sandimune 14 mg/kg i.p.) injections 2 days prior to stem cell injection in order to suppress the immune response. One female control guinea pig received an injection of vehicle only, and the remaining guinea pigs received injections of vehicle containing stem cells. An additional group of four normal, non-sound-induced and non-injected guinea pigs was used in obtaining cells counts (see below). The animals were exposed to a 1−4 kHz filtered noise band at 112 dB SPL for 72 hr. Thereafter, the animals received oral doses of cyclosporine (Neoral 6 mg/kg) for the six-week duration of the study. Perfusion through the cochlea was performed as previously described for drug administration and subsequent anatomical studies (Bobbin et al., 2003). The guinea pigs were removed from the noise exposure, directly anesthetized, and an opening made in the bulla as described previously (Bobbin et al., 2003). An input opening (∼0.25 mm) was drilled into the basal turn of the scala tympani and an effluent hole was drilled into the horizontal vestibular canal using a hand drill. Stem cell cultures were resuspended at 40,000 cells/μl in artificial perilymph (137 mM NaCl; 5 mM KCl; 2.5 mM CaCl2; 1 mM MgCl2; 10 mM D-glucose; 10 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES, Gibco); 2 mM Na pyruvate; 2 mM creatine, pH 7.4.adjusted with NaOH) and stored in ice until use (within 1 hour). Stem cells were perfused through all scalae of the cochlea (2.5 μl/min) for 15 minutes using a glass electrode affixed to a 1 ml pipette. The presence of stem cells entering the cochlea and within the effluent was confirmed visually. Animals received 50 mg/kg of the antibiotic enrofloxacin (Baytril) two times daily for five days post surgery. Guinea pigs were allowed to recover for 6 weeks. All guinea pigs except one female survived up to this time point. At 6 weeks after the animals were anesthetized with urethane (1.5 g/kg, i.p.), the cochleas were removed, the round window and oval windows opened and 4% paraformaldehyde was perfused through the perilymph scala. The cochleas remained in the paraformaldehyde for 4−8hrs, then were added to phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 8% EDTA and stored for four weeks at 4 °C. Cochleas were embedded in paraffin and cut into 6 μM sections and stored at 23 °C until use.

5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-beta-D-galactopyranoside (X-gal) Detection

Cryosections were washed in rinse solution (PBS, 2mM MgCl2, 2mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA), pH 7.6) twice for 10 min each. Next, sections were post-fixed in iced methanol for 10 min, permeablized in detergent solution (rinse solution supplemented with 0.01% sodium desoxycholate and 0.02% NP40, Sigma) at 4 °C for 10 min and incubated in X-gal reaction solution (rinse solution supplemented with 5 mM potassium ferrocyanide, 1 mg/ml X-gal, Molecular Probes) at 37 °C overnight. Afterwards, sections were rinsed in 1 X PBS + MgCl2 + EGTA pH 7.6 three times for 5 minutes each and mounted for detection.

Immunohistochemistry

Sections were washed twice in PBS, then permeablized in 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma), 3% normal serum (specific for the species in which the secondary antibody was raised; Jackson Immuno Laboratories, West Grove, PA), 0.3% Triton X-100 (Sigma), 0.3% H2O2 (for biotinylated antibodies only) in 1 X PBS. Next, samples were incubated 45 minutes at 23 °C in humid environment with primary antibodies diluted in the above solution, then washed three times in PBS, and incubated with the secondary antibody at 1:200 in the above solution for 45 minutes at 23 °C. The monoclonal and/or polyclonal primary antibodies used were directed against β-III tubulin (rabbit, Covance, Princeton, New Jersey); β -galactosidase, GFAP (mouse, Sigma); β -galactosidase, Map-2 (mouse, Chemicon, Temecula, California); BrdU (sheep, Capralogics, Hardwick, Massachusetts); Calbindin, neurofiliment (NF) 68, NF-medium, p75 (rabbit, Chemicon); Myosin 6 (rabbit, gift from Tama Hasson, UCSD); Myosin 7a (rabbit, gift from Tama Hasson, UCSD); NF 200 (rabbit and mouse, Sigma); Oncomodulin (polyclonal), S100β (rabbit, Swant, Bellinzona, Switzerland); synapsin (rabbit, Calbiochem, San Diego, California). Samples were then incubated for 45 minutes to 2 hrs with secondary antibodies directed against the species in which the primary antibody was raised. The samples labeled with either 1:200 FITC donkey anti-sheep; Texas Red rabbit anti-sheep (Jackson ImmunoResearch); 1:1000 Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit, mouse (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon); 1:1000 Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-rabbit, mouse (Molecular Probes) or 1:200 Texas Red goat anti-rabbit, mouse (Molecular Probes). Next, the samples were washed three times in PBS and mounted in Vectashield mounting medium with 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, California) for fluorescence detection. The samples labeled with biotinylated secondary antibodies were treated as described in the Vectastain ABC kit, developed with either 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) or Vector VIP substrates, counterstained with methyl Green, dehydrated and mounted with Vectamount (all from Vector Laboratories). The mouse on mouse (M.O.M.) antibody labeling kit (Vector Laboratories) was used with all primary antibodies that were raised in mouse. Images were captured using a SPOT digital camera (Spot Diagnostic Instruments, Inc, Sterling Heights, Michigan) and mounted to either a Nikon TE200-U or E800 fluorescent microscope. Images were processed using SPOT v.3.5.6 software.

Y-chromosome fluorescence in situ hybridization

In mice, the detection of the LacZ construct (by either X-gal labeling or immunohistochemical labeling to β-galactosidase) in the transplanted cells decreased by 4 weeks after injections (Figure 2E). Therefore, we sought to establish a method to detect the presence of the injected cNSCs over the long term. Detection of male (XY) chromosomes in female (XX) host using fluorescence in vitro hybridization (FISH) has been a useful tool for differentiating transplanted from endogenous cells (Deb et al., 2003; Ismail et al., 2002; Weimann et al., 2003). We processed the cochleas obtained from five female guinea pigs (1 vehicle-injected control, 4 stem cell-injected) for Y-chromosomal FISH labeling. Sections were processed following manufacturer's specifications for either fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) conjugated probes directed against the pan centromeric region of the murine Y chromosome (ID Laboratories, Ontario, Canada), or biotinylated probes directed against the pan-centromeric region or whole murine X and Y chromosomes (ID Laboratories and Cambio, Cambridge, United Kingdom). Biotinylated probes were subjected to an additional 10 minute incubation with either Avidin DCS FITC or Avidin DCS Texas Red (Vector Laboratories). After hybridization, sections were then mounted in Vectashield with DAPI (Vector Laboratories) for imaging and stored at 4°C until immunohistochemistry was performed. Sections chosen for immunohistochemistry were then washed, treated with Antigen Unmasking Solution (Vector Laboratories) as described by the manufacturer and then subjected to immunolabeling. Positive signals met four criteria: 1) they were single punctate signals, 2) they were specific to either the green (FITC conjugated) or red (Avidin DCS Texas red) channel, 3) they co-localized to the nucleus, and 4) they exhibited a low degree or absence of background (non-nuclear fluorescence). Slides processed from injected ears were compared to similarly processed sections obtained from male ears (Y-probe positive control, Figure 3), non-injected female ears, vehicle-injected female ears, and ears that received the Y-probe vehicle 1x saline-sodium citrate buffer (SSC) (Y-probe negative controls, data not shown).

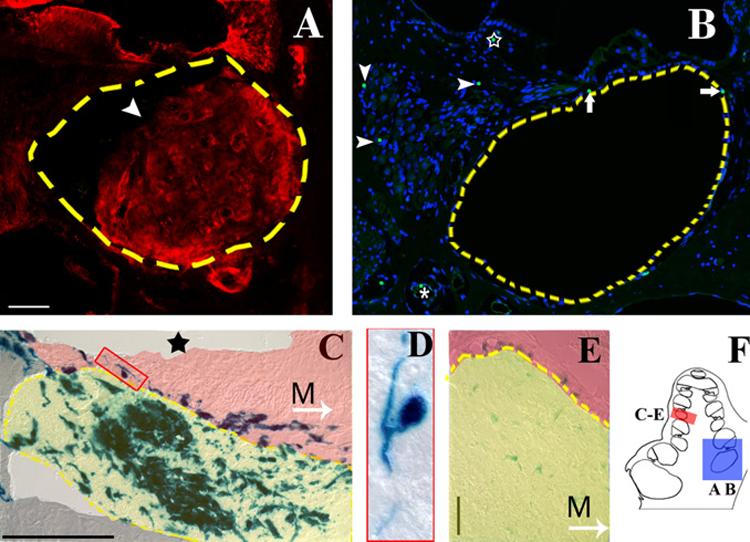

Figure 2. cNSCs migrate into the sound-damaged cochlea.

A) Round window injections into the murine cochlea resulted in a bolus of cells (arrowhead) located in the basal turns of the scala tympani (broken line). β-galactosidase positive cells (Texas red) were observed in the bolus itself, as well as in the spiral ganglion, spiral limbus, organ of Corti, and spiral ligament. Nonspecific labeling was observed in the spiral limbus and tectorial membrane. B) Perfusion throughout the cochlea and vestibular system failed to produce obstruction the basal turns of the scala tympani; however, transplanted cells were observed within the cochlear tissue. A mid-turn view of a female guinea pig cochlea shows Y- positive cells (green FITC punctate label localized to the DAPI labeled nucleus in blue) lining the scala tympani (arrows) and blood vessel (asterisk), and within the spiral ganglion (arrow heads) and spiral limbus (star). Blue= nuclear DAPI label, green= FITC labeled Y-chromosome. C) X-gal labeling of a murine cochlea two weeks after transplantation shows that transplanted cells within the scala tympani (highlighted in yellow) primarily exhibit an amorphous morphology. Some cells that migrated into the osseous spiral lamina region (highlighted in red) exhibited a pseudounipolar neural morphology (box). The sound stimulus has ablated any remaining cells of the organ of Corti (star indicates the location of the organ of Corti in a control animal). M, Arrow = direction to modiolus. D) Detail of cell outlined in box of (C). E) X-gal labeling of the bolus within the scala tympani (outlined in yellow) 4 weeks after transplantation illustrates a decrease in LacZ expression over time. The spiral ganglion region is highlighted in red. M, Arrow = direction to modiolus. F) Schematic highlights the representative regions for A and B (blue box) and C-E (red box). Broken line = scala tympani boundary. Scale bars=50 μM.

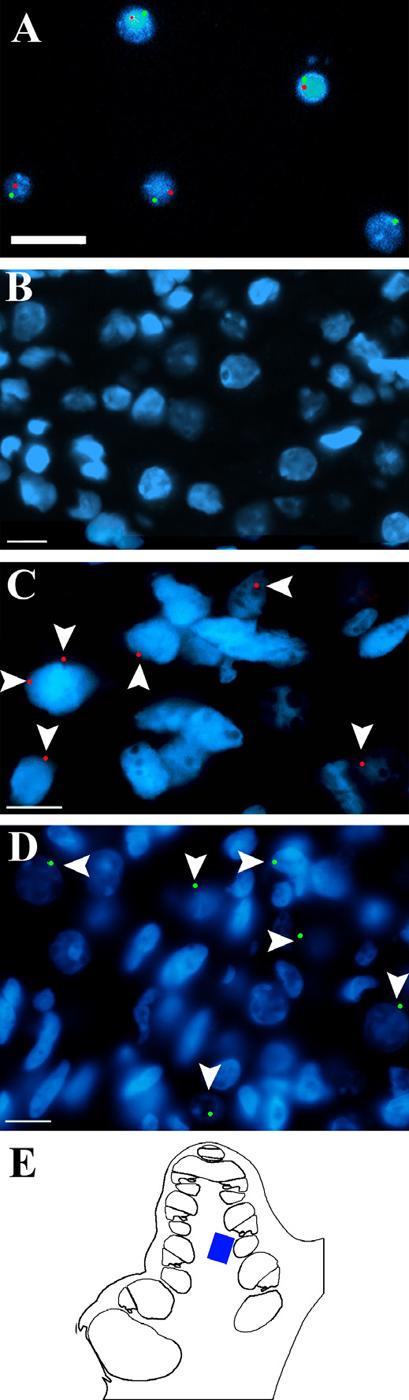

Figure 3. FISH labeled Y-chromosome in XY cNSCs.

A) Clonal NSCs obtained from a male mouse were cultured 2 days, fixed, and processed for FISH by using biotinylated X (Texas red) and Y (FITC, green) probes (Cambio). A positive signal is indicated by the presence of a single punctate signal that co-localizes with the nuclear DAPI staining (blue). B) Negative control section through the spiral ganglion of a female guinea pig that was injected with NSC vehicle and hybridized with the FITC (green) conjugated Y-probe (ID Laboratories) shows no labeling. C) Similar section of a non-injected male guinea pig that was hybridized with the biotinylated Y-probe (Texas red) shows an abundance of labeling (arrowheads). Not every cell is labeled because the narrow width of the sections (6 μM) would exclude some Y-chromosomes from the slide. D) Section through the spiral ganglion of a female guinea pig that was injected with male stem cells and then hybridized with the FITC (green) conjugated Y-probe exhibits labeling of single punctate signals (arrow heads) that co-localize with the nuclear DAPI staining (blue). E) Schematic highlighting the region of the cochlea where images B-D were obtained. Arrows = positive Y chromosome label. Scale bar = 10 μM. DAPI (blue) stains nuclei in all panels.

Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Three postnatal day zero FVB mice were decapitated. Whole brains were removed, flash frozen, and stored at −80°C until use. Next, brains were homogenized on ice in lysis buffer containing 7% β-mercaptoethanol and stored in ice until RNA extraction. Total RNA was extracted from brain homogenate and 2 day cultured cells using the Stratagene Absolutely RNA RT-PCR Miniprep Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, California) and RNA concentrations were determined by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm on a spectrophotometer. Reverse transcriptase was performed per Prostar First-Strand RT-PCR kit's instructions (Stratagene). Previously published PCR primers were used when possible (Table 1). PCR conditions were dependent upon primer sequences. Beta-actin primers were used as a positive control as per Stratagene directions. RNA samples run with no reverse transcriptase were used as negative controls in subsequent PCR runs. Gel electrophoresis was performed using 1% agarose gels, containing 0.5μg/ml ethidium bromide (EtBr) at 120V. PCR products were visualized under UV light.

Table 1.

Summary of RT-PCR product size, annealing temperature, and primer sequences.

| PCR Product | Size (bp) | Ann. T (°C) | Sequence (fwd) | Sequence (rev) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-actin | 514 | 60 | tgtgatggtgggaatgggtcag | tttgatgtcacgcacgatttcc |

| Aquaporin 4 | 610 | 55 | atggtggctttcaaaggggt | gatgggcccaacccaatatat |

| Calbindin 45 | 440 | 58 | cgcactctcaaactagccg | cagcctacttctttatag cgca |

| Connexin 26 46 | 365 | 55 | cggaagttcatgaagggagagat | ggtcttttggacttccctgagca |

| GFAP 47 | 149 | 55 | gttgtgaaggtctattcctgg | tcccttagcttggagagcaa |

| Math1 48 | 199 | 58 | agtgacggagagtttcccc | ctgcagccgtccgaagtcaa |

| Myosin 6 | 932 | 57 | ccgggagatagtggataacc | ccagcacagagcctgtagaa |

| Myosin 7a | 789 | 57 | gctgacaactgctacttcaac | gctgttcacagtgaagttctc |

| Oncomodulin 49 | 292 | 55 | atcttcccatctccatcgtt | tgtgcatcacggacattctg |

| S100β 50 | 227 | 65 | gactccagcagcaaaggtgac | catcttcgtccagcgtctcca |

Cell counting and statistical analysis

DAPI labeled differential interference contrast (DIC) images were obtained from axial sections through cochleas of normal, non-sound-damaged, non-injected guinea pigs (N=4), sound-exposed, cNSC-injected guinea pigs (N=4), and sound-exposed, non-injected contralateral cochleas of the previous group (N=4). To avoid counting the same cells more than once, only non-adjacent serial sections were counted. These criteria resulted in the use of approximately 50 axial sections per cochlea in this analysis. Turn number was established as follows: The hook region was identified and the wide basal turn (the first turn apical to the hook) was labeled turn 1.0. The spiral ganglion cells medial to this turn were grouped as turn 1.0 as well. The next apical region opposite the modiolus, and the collection of spiral ganglion cells medial to this region, were labeled turn 1.5, and so on. Type I spiral ganglion neurons were identified by morphology and counted in each turn by superimposing a 100 μM X 100 μM box on the spiral ganglion image and counting cells within each box (Spot Software V3.5.6, Diagnostic Instruments, University of New South Wales, Australia). This method allowed for an average of three 10,000 μM2 boxes to be counted per cochlear turn. Deiters' cells, hair cells, and pillar cells were identified by morphology and subsequently counted in each turn. Cell counts were obtained from each turn of the cochlea and were verified by a double blind protocol. Statistical significance was measured by using paired-samples T-test (α=0.05) and values are presented ± standard error of the mean. All of these experiments have been approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees of both LSUHSC and Children's Hospital-Boston.

Results

Sound damage

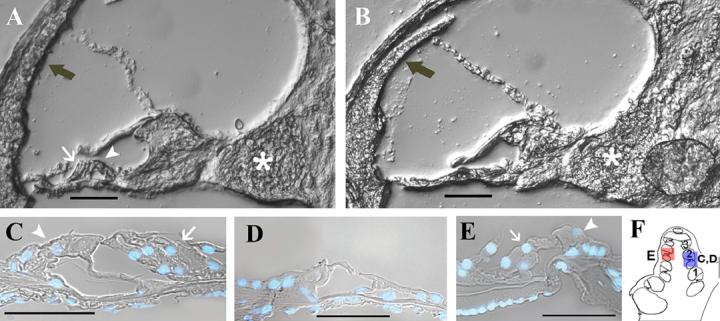

We used two animal models, mouse and guinea pig, in these experiments. First, we set out to describe the structural damage produced by our sound stimuli. The damage caused by the noise exposure in the mouse was consistent with previously reported results (Wang et al., 2002) and involved damage to many different cell types including cells of the stria vascularis, hair cells, and supporting cells of the organ of Corti (Figure 1). In the guinea pig, the second cochlear turn corresponded with the frequency of the sound stimulus and received the most severe structural damage from the noise exposure (Figure 1C, D). Cell counts indicated that the amount of cell loss decreased basal-ward and apical-ward of this damaged area.

Figure 1. Sound induced damage in the murine and guinea pig cochlea.

A) DIC image of the second turn of a murine control cochlea. B) The second cochlear turn of a sound-damaged littermate of A) shows the resulting structural damage after two weeks of intense noise (8−16 kHz, 2hr, 105 dB SPL). This damage includes death or destruction of cells of the stria vascularis (grey arrow), organ of Corti, and swelling of the spiral ganglion neurons (asterisk). C) DAPI-stained nuclei superimposed on DIC image of the organ of Corti in the second turn from a control guinea pig cochlea illustrates the normal inner (white arrowhead) and outer hair cell (white arrow) morphology. D) Six weeks after exposure to intense sound (1−4 K Hz, 72 hr, 115 dB SPL), guinea pig cochleas exhibited loss of outer hair cells and most supporting cells in the second cochlear turn (outlined with the blue box in F). This stimulus produces a gradient of cell loss that is most severe in this region. E) The damage extends apical from the second turn of the cochlea; however, the third turn of a guinea pig sound-damaged cochlea (outlined with the red box figure F) shows the presence of some surviving supporting cells in addition to outer and inner hair cells. Therefore, this turn exhibits less structural damage than the second turn. F) Schematic highlighting the representative regions for C and D (blue box) E (red box). Scale bar = 50μM

cNSCs integrate into the spiral ganglion and organ of Corti

Next, we sought to describe the extent of cNSC integration when injected into the scala tympani of sound-damaged animals. Mice received injections through the round window (Materials and Methods) and this approach resulted in a bolus of cells in each animal that was observed histologically in the basal scala tympani of the cochlea that approximated the injection site (Figure 2). The cells in the bolus were stem cell-derived as shown by being both positive to the B-galactosidase antibody (Texas red, Figure 2A) and exhibiting the X-gal labeling product (Figure 2C). Some of the X-gal labeled cells had adopted a soma and axonal morphology resembling neurons (Figure 2C, D).

Although these results suggest that the sound-damaged cochlea may support injected cells, the methodologies for cNSC injection and detection warranted refinement. Foremost, the presence of a cell mass in the scala tympani is problematic because it would presumably alter the normal physiology of the cochlea. Therefore, we sought an alternative method of cell perfusion throughout the cochlea (discussed below). In addition, we experienced a problem with long-term detection of the transplanted cells. Although there was a robust signal 2 weeks after implantation, there was a decrease in both X-gal and β-galactosidase antibody labeling at 4 weeks in mouse (Figure 2E). Therefore, a FISH protocol was adopted for the long-term detection of the transplanted cells. In this protocol, the injected male cNSCs (XY) were identified in female (XX) guinea pig hosts by FISH labeling of the Y chromosome. We demonstrated the validity of the method by showing FISH label in male mouse cNSCs (Figure 3A); the absence of FISH label in the spiral ganglion cell area of a female guinea pig not injected with stem cells (Figure 3B); the presence of FISH label in the male guinea pig spiral ganglion cell area (Figure 3C), and the presence of FISH label in the spiral ganglion cell area of a female guinea pig that was injected with male NSCs six weeks prior (Figure 3D). These results indicate that FISH may be used for long-term detection of the Y chromosome in histological sections.

In an attempt to eliminate the bolus of cells that accumulated in the basal turn, and to obtain a larger distribution of cells throughout the cochlea, we used a method that perfused cells throughout the cochleas and vestibular system of guinea pig (Materials and Methods). How far along the perfusion route the stem cells remained suspended in the vehicle could not be determined. However, the mortality rate in guinea pig (7%) was less than in mice (50%). In contrast to the round window injection method used in mice, there was no observable cell mass in the any of the cochleas of guinea pigs receiving a perfusion of cells (Figure 2B). However, it is possible that the failure to detect a cell mass in any scala of the guinea pig cochlea may have been due to the fixation procedure that washed fixative through the scala which could have pushed any small mass out of the cochlea. In any case, FISH labeling showed that Y-positive cells were observed throughout the cochlea of all injected animals (N=4) which indicates that cells migrated from the scala tympani into Rosenthal's canal and the organ of Corti (Figure 2B). Interestingly, no cells were observed in the vestibular organs of any injected animal even though cells were perfused throughout the entire perilymphatic system. We presume this is because sound exposure failed to produce damage to these organs.

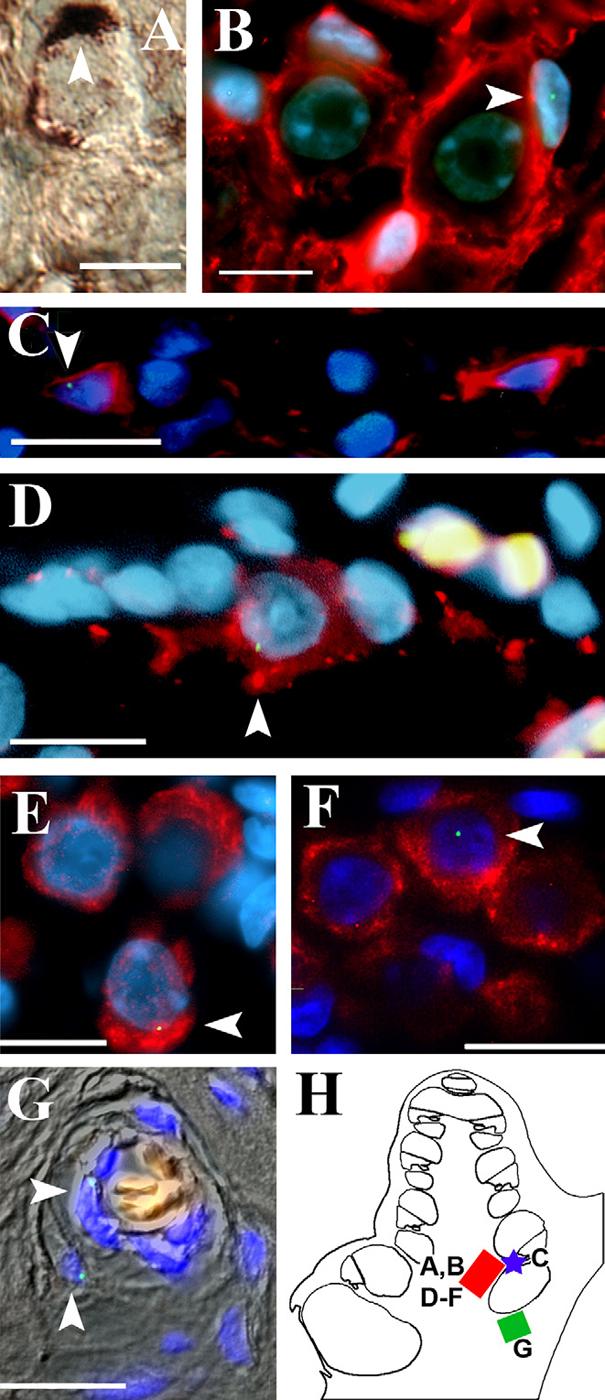

The greatest number of cells labeled with cNSC markers were found in the spiral ganglion area of the basal turn and some were associated with blood vessels (Figure 4). In the spiral ganglion area, cNSC markers were found in what appeared to be satellite cells (thin nuclei with cytoplasm that enfolds adjacent soma of spiral ganglion neurons) (Figure 4A, B). FISH identified the presence of the Y chromosome in nuclei of satellite and Schwann cells (thin nuclei, cytoplasm non-adjacent to spiral ganglion soma) in the spiral ganglion area and in the osseous spiral lamina (Figure 4C) of female hosts. These cells also labeled for S100β, which is normally expressed in both undifferentiated cNSCs in vitro (Figure 5) and endogenous cochlear satellite and Schwann cells. In addition to satellite cells, some FISH positive cells in the spiral ganglion area appeared to have a large soma and nucleus, suggesting they were adapting the morphology of spiral ganglion neurons, and they stained positive for the spiral ganglion neuronal markers neurofiliment 200 kDa (NF 200) and BIII-tubulin (Figure 4D, E). These markers are not expressed in undifferentiated cNSCs (data not shown), which suggests that the cochlea exerts some influence on cNSC differentiation. FISH positive cells also labeled for synapsin (Figure 4F) suggesting further differentiation. Other FISH positive cells were found to be associated with blood vessels in the bone of the cochlea (Figure 4G).

Figure 4. Transplanted cNSCs differentiate into satellite cells and neuronal cells in the cochlear spiral ganglion.

Most of the transplanted cNSCs that localized within the spiral ganglion exhibited a neural morphology and expression pattern. A) Immunolabeling of a mouse cochlea 4 weeks after transplantation for anti-β-galactosidase (DAB, brown) shows a cNSC (white arrowhead) in the spiral ganglion region that exhibited the morphology of a satellite cell, with its cytoplasm enveloping the large round soma of endogenous type I spiral ganglion neuron. B) Similarly, guinea pig sections subjected to FISH labeling of the Y chromosome (FITC, green) in female (XX) hosts showed that injected cNSCs (XY, white arrowhead) exhibiting the satellite cell morphology expressed the satellite/Schwann cell marker s100β (Texas red) when localized to the spiral ganglion. C) Y-positive cells that located to the osseous spiral lamina exhibited a thin nucleus (DAPI, blue) and s100β (Texas red) labeling which is characteristic of Schwann cells that populate this region. In addition to satellite and Schwann cell morphologies, many transplanted cells that localized to the spiral ganglion region adopted the morphology and expression pattern of endogenous Type I spiral ganglion neurons. D) Example of a Y-positive cNSC (white arrowhead) in the spiral ganglion that adopted a large soma and nucleus similar to the morphology of an endogenous spiral ganglion cell. Cells of this morphology express the neuronal markers NF 200 (D, Texas red) and βIII-tubulin (E, Texas red). F) Additionally, these large soma Y-positive cNSCs (white arrowhead) exhibited synapsin labeling (Texas red) similar to endogenous Type I spiral ganglion cells. G) DIC overlay showing Y-positive cells (white arrowhead) localized to blood vesicle within the cochlear boney labyrinth. Red blood cells within the lumen autofluoresce orange. H) Schematic highlighting the regions of study for this figure. Images A, B, and D-F were obtained from the basal spiral ganglion region (red box) in different animals. Image C was obtained from the basal osseous spiral lamina (blue star). Image G was obtained from the boney labyrinth as indicated in the green box. Scale bars = 10 μM.

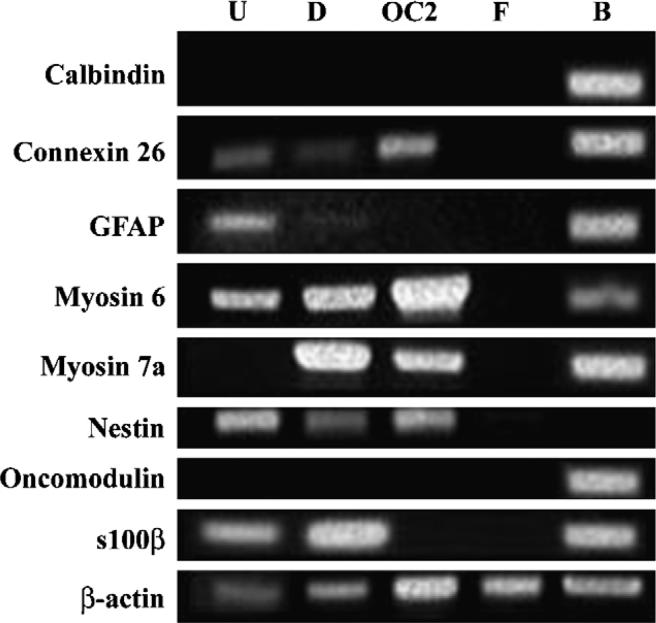

Figure 5. Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) indicates NSCs exhibit neural and cochlear gene expression.

Total RNA isolated from NSCs cultured in undifferentiating (U) or differentiating (D) conditions was compared to total RNA isolated from the OC2 cell line (OC; cochlear cell type positive control), a commercially available human fibroblast cell line (F; negative control), and whole brain (B; positive control). Undifferentiated NSCs express myosin 6 and low levels of connexin 26. Myosin 6 and 7a are upregulated in cNSCs in differentiating conditions (media supplemented with 10 μM mitomycin c for 10 days). As discussed in the Results section, these NSCs express GFAP and s100β as well as the neural progenitor marker nestin. Notably, these NSCs fail to express either oncomodulin or calbindin in vitro.

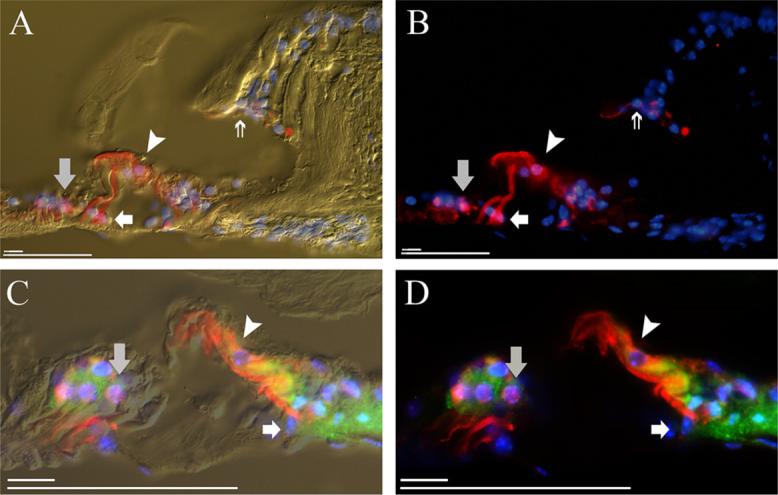

In addition to the spiral ganglion, cells labeled with cNSC markers were also found in the organ of Corti (Figures 6, 7 & 8), particularly in regions of the organ of Corti exhibiting incomplete destruction (Figure 1E). In mice, β-galactosidase labeled cells were found in the areas occupied by interdental cells of the spiral limbus, inner phalangeal cells, inner hair cells, pillar cells and Deiters' cells (Figure 6A, B). The supporting cell marker glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) was co-expressed in β-galactosidase labeled cells in the area of Deiters' cells (grey arrow in Figure 6C, D), however, cells in the areas of the pillar cells or the inner hair cells failed to label with GFAP (white arrow and arrowheads in Figure 6C, D). This is another example illustrating that cNSCs express different markers depending upon their localization within the cochlea.

Figure 6. Stem cell integration into the organ of Corti supporting cell layer.

A) Anti-β-galactosidase labeling (Texas Red) of the murine cochlea shows cNSC localization to the interdental cell region of the spiral limbus (double arrow), inner phalangeal cell layer (asterisk), inner hair cell region (arrowhead), pillar cell region (white arrow), and Deiters' cell region (grey arrow). Cell nuclei are labeled with DAPI (blue). Non-injected ears failed to exhibit fluorescent β-galactosidase labeling (data not shown). B) Fluorescence image of A. C) β-galactosidase+ (Texas Red) cNSCs that localize to the pillar cell region (white arrow) of the murine cochlea and the inner hair cell region (arrowhead) do not express the supporting cell marker GFAP (FITC, green), while Deiters' cells (grey arrow) and cells of the inner sulcus double label for GFAP. D) Fluorescence image of C. Scale bars = 10 μM, 50μM.

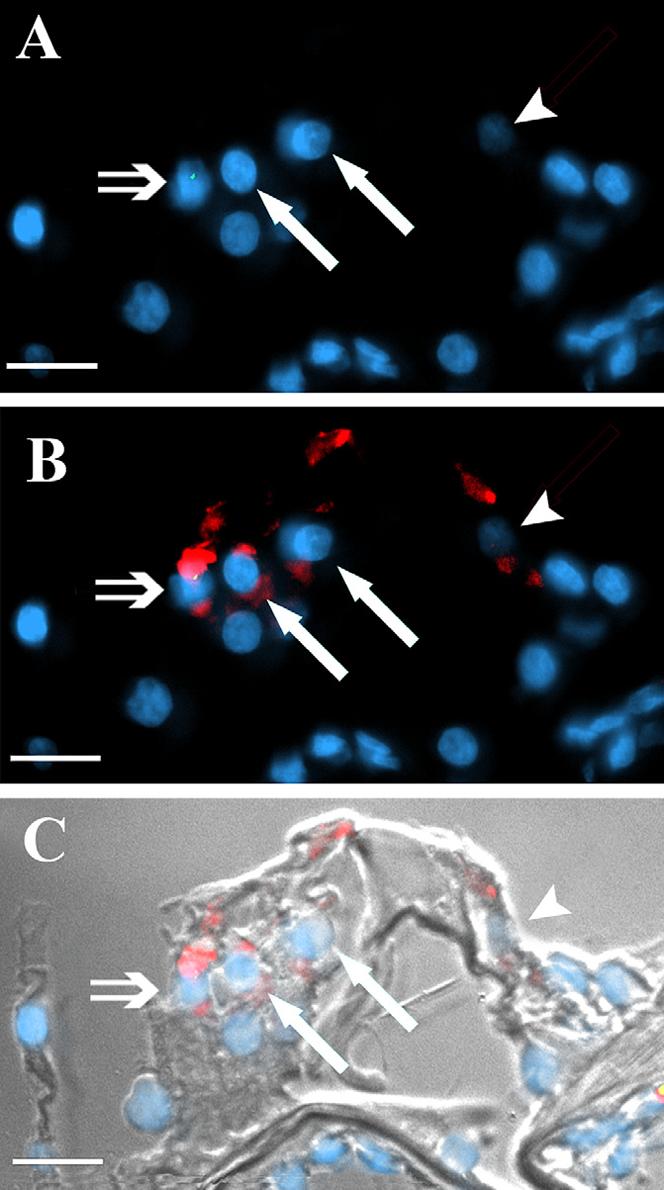

Figure 7. cNSCs localize to the hair cell layer and express hair cell proteins.

A) Y-FISH labeling (green dot) identifies a cNSC (double arrow) in the third row of outer hair cells (white arrows) in the sound-damaged guinea pig cochlea. B) Overlay showing myosin 7a labeling (Texas Red) indicates that this cell expresses myosin 7a, as do the endogenous outer hair cells of the other two rows (white arrows) and the inner hair cell (arrowhead). C) DIC overlay of B. This image was recorded from the region of the cochlea highlighted by the red box in Figure 1 F. Scale bars = 10 μM.

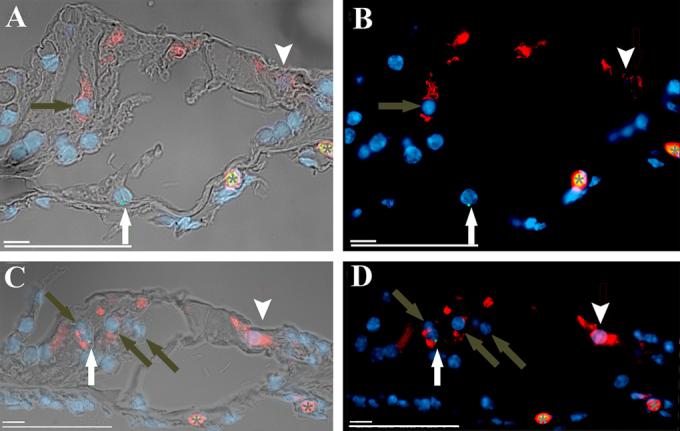

Figure 8. cNSC conditional expression of hair cell markers after transplantation into the sound-damaged guinea pig cochlea.

A) A Y-FISH labeled cNSC in the pillar cell region (white arrow) shows that cNSCs localized to the guinea pig pillar cell region do not express the hair cell marker oncomodulin (Texas Red), which is seen in the endogenous inner (arrowhead) and outer (grey arrow) hair cells. B) Fluorescence image of A. C) Similar FISH labeling shows that cNSCs that localize to the outer hair cell region (white arrow) do upregulate the hair cell protein oncomodulin and show similar levels of expression to the endogenous outer (grey arrows) and inner (arrowhead) hair cells . D) Fluorescent image of E. Red blood cells (asterisk) in the cochlear vein autofluoresce in both the green and red channels producing a yellow-orange overlay. This image was recorded from the region of the cochlea highlighted by the red box in Figure 1F. Scale bars = 10 μM, 50μM.

In all of the stem cell transplanted female guinea pig cochleas subjected to FISH (N=4), Y-positive labeling was found in the area of what would normally be occupied by a row of outer hair cells (OHCs), albeit in low numbers (Figure 7, Table 2). Twenty-six FISH labeled cells were detected in the outer hair cell regions of all injected ears. Figure 7B shows an example of a FISH labeled cell that co-expressed myosin 7a (double arrow) as well as two non-FISH labeled endogenous OHCs (white arrows). Similarly, a FISH label in a cell that appears to be in the OHC region (white arrow Figure 8C, D) did stain for the hair cell marker oncomodulin as did the remaining endogenous OHCs that were not labeled with FISH (grey arrows). Interestingly, a FISH labeled cell found in the region of the outer pillar cells did not stain for oncomodulin (white arrow Figure 8A, B), even though it localized one cell-length away from the hair cell rows. This suggests that the differentiation of the transplanted cells is influenced by their localization within the organ of Corti.

Table 2.

Number of Y-positive cells located within the Organ of Corti. This table lists both the regions within the organs of Corti and the total numbers of FISH identified Y-positive cells in all of the transplanted animals. At least three transplanted animals exhibited cells located in the described regions.

| Organ of Corti Region | Number of Y-positive cells |

|---|---|

| Outer Hair Cell | 26 |

| Inner sulcus | 5 |

| Spiral Ligament | 5 |

| Spiral Limbus | 5 |

| Dieter's | 5 |

| Outer sulcus | 5 |

| Inner Hair Cell | 4 |

| Pillar cell | 4 |

| Interdental | 4 |

| Stria Vascularis | 3 |

| Inner phalangeal | 3 |

Cochlear microenvironment influences cNSC differentiation

In order to examine whether the cochlear environment influenced cNSC differentiation, we obtained a baseline analysis of cNSC expression using RT-PCR prior to transplantation (Figure 5). We found that undifferentiated NSCs express several CNS markers in vitro that are also expressed in cochlear tissues such as the glial markers s100β and GFAP; connexin 26, which is expressed in supporting cells of the cochlea; and myosin 6, which is a hair cell marker in the cochlea. When NSCs were exposed to differentiating conditions in vitro (0.5 mM mitomycin c), they exhibited an upregulation of myosin 7a which is a specific hair cell marker in the cochlea, and a down regulation of GFAP. NSCs failed to express the hair cell markers calbindin and oncomodulin when cultured in either undifferentiating or differentiating conditions. Foremost, these results indicate that these NSCs possess the capacity to express some cochlear markers; therefore, they may be suitable for use in a model for cochlear repair. Furthermore, these results provide a framework in which to analyze any influence of the cochlear environment on NSC expression. If a transplanted NSC would upregulate a cochlear marker not normally expressed in vitro, such as oncomodulin, the argument could be presented that the cochlear environment bears an influence on NSC development.

We found that the morphology and protein expression of transplanted cNSCs was dependent upon their localization within the cochlea. Some of the cells that labeled for cNSCs in the spiral ganglion exhibited both the morphology and protein expression pattern (S100β+, NF 200−, neurofiliment medium [NF M]−, βIII tubulin−) of spiral ganglion satellite cells (Table 3; Figure 4). In addition to satellite cells, some cells that labeled as cNSCs in the spiral ganglion exhibited both the phenotype and expression pattern (NF 200+, NF M+, βIII tubulin+, S100β−) of spiral ganglion neurons (Table 3; Figure 4). In addition, cNSCs exhibited synapsin labeling similar to local endogenous cells (Figure 4F), which suggests that they contained the synaptic machinery required for synaptic transmission.

Table 3.

Summary of cNSC cochlear localization and protein expression. This table lists those markers that were expressed in transplanted cNSCs. In most cases, cNSCs had upregulated those markers that are expressed by endogenous cells of the microenvironment.

| cNSC Localization | Mouse | Guinea Pig | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expressed | Not Expressed | Expressed | Not Expressed | |

| Inner hair cell | myosin 7a+ | GFAP- | No Observed Localization | |

| Outer hair cell | No Observed Localization | calbindin+/-, myosin 7a+, oncomodulin+ | NF200- | |

| Pillar cell | βIII tubulin+ | p75-, GFAP- | † | calbindin-, oncomodulin- |

| Deiters' cell | GFAP+ | βIII tubulin-, myosin 7a-, NF 200- | GFAP+ | myosin 7a-, S100β- |

| Inner phalangeal cell | GFAP+ | myosin 7a-, NF 200- | GFAP+ | calbindin-, myosin 6-, oncomodulin-, S100β- |

| Spiral ganglion neuron | NF 200+, βIII tubulin+, myosin 7a+, | S100β-, GFAP- | βIII tubulin+, NF 200+, NF M+ | calbindin-, oncomodulin-, S100β- |

| Satellite cell | MAP-2+, S100β+ | NF 200- | GFAP+, S100β+ | βIII tubulin-, myosin 7a, NF 200-, NF M-, oncomodulin- |

| Schwann cell (oss. spiral lamina.) | βIII tubulin+ | NF 200-, GFAP- | S100β+, GFAP+ | calbindin-, NF68-, NF200-, myosin 6- |

| Schwann cell (VIIIth Nerve Trunk) | No Observed Localization | S100β+ | myosin 7a-, NF200- | |

| Spiral limbus (Interdental cell) | βIII tubulin+ myosin 7a+, S100β+ | GFAP- | S100β+ | NF200-, oncomodulin- |

| Spiral ligament | myosin 7a+, S100β+ | GFAP- | S100β+ | NF68-, NF200- |

| Bony labyrinth | No Observed Localization | † | myosin 7a-, NF200-, NF68-, S100β- | |

Key: (+) = immunohistochemistry positive; (-) = immunohistochemistry negative; (+/-) = in sections with positive calbindin labeling to endogenous cells, stem cells exhibited variable calbindin expression. Bold = immunolabeling not expected in endogenous tissue. (†)= could not determine expression due to lack of antibodies appropriate for paraffin sections

Similar to those observed in the spiral ganglion, cells labeled as cNSCs in the organ of Corti region expressed different markers depending upon their localization within the organ. However, unlike those in the spiral ganglion, none of the cells labeled as cNSCs in the organ of Corti also labeled for neuronal proteins such as NF 200 or NF M (Table 3). It should be noted that hair cells label with NF M during development but down regulate this marker by postnatal day 21 (Hasko et al., 1990). In our study, neither endogenous hair cells nor transplanted cells that localized to the organ of Corti labeled with NF M. However, as previously noted, cells labeled as cNSCs in the supporting cell region expressed GFAP, which is normally expressed in supporting cells (Figure 6C, D) (Rio et al., 2002). In contrast, GFAP could not be detected in cells labeled as cNSCs in the pillar cell region, a result which mirrors GFAP− expression of endogenous pillar cells (Rio et al., 2002). RT-PCR of cells in culture demonstrated that these cNSCs express GFAP prior to implantation (Figure 5). Therefore, transplanted cNSCs appear to differentially regulate GFAP depending on their location within the organ of Corti.

Prior to transplantation, undifferentiated cNSCs do not express the hair cell markers myosin 7a, oncomodulin, and calbindin (Figure 5). However, cells labeled as cNSCs in the hair cell region expressed these hair cell markers (Figures 7 & 8, Table 3). In the normal cochlea, myosin 7a is selectively expressed in hair cells. In our experiments, myosin 7a expression was observed in cells labeled as cNSCs in the hair cell region of the organ of Corti (Figure 7), but not in supporting cell regions in the organ of Corti (Table 3). Similarly, oncomodulin was differentially expressed depending upon the location of cNSC label within the organ of Corti. We used a commercially available polyclonal antibody to oncomodulin which labels both inner and outer hair cells of the cochlea (Sakaguchi et al., 1998). cNSCs failed to label with this antibody when cultured in either proliferating or differentiating conditions in vitro (data not shown). In vivo, the cNSC labeled cells in the pillar cell region did not express the hair cell marker oncomodulin (Table 3; Figure 8 A, B). However, cNSC labeled cells that localized to the OHC layer expressed oncomodulin in a similar manner as endogenous OHCs (Table 3; Figure 8 C, D). Similar to oncomodulin, the hair cell marker calbindin was found only in those cNSCs labeled cells that had localized to the outer hair cell region (Table 3). These results indicate that the microenvironment of the cochlea may influence cNSC expression.

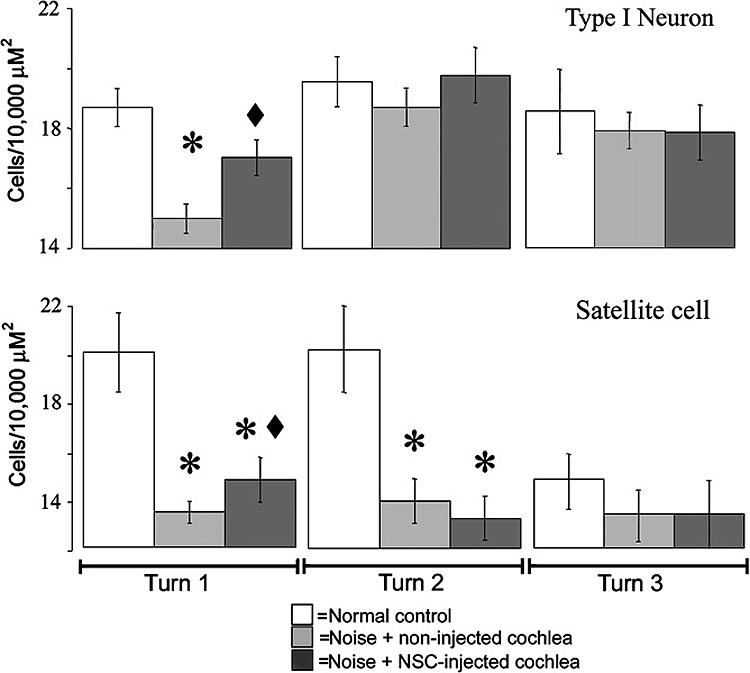

Quantification of cochlear cell loss

We tested the hypothesis that the application of stem cells into the scala tympani led to a significant alteration in the number of cochlear cell types missing due to the noise exposure (Figure 9). The number of cells present within each mid-modialar cross section of the cochlea was measured either by a direct count of all of the cells within the organ of Corti or by a measurement of cell density within the spiral ganglion (Materials and Methods). Cells were counted in normal guinea pigs (N=4), noise-damaged guinea pigs that received cNSC injections (N=4), and the non-injected noise damaged contralateral cochleas of the previous group (N=4). The results indicate that the sound damage produced a significant decrease in the density of Type I spiral ganglion cells (n= 15.1 ± 0.5 cells/10,000 μM2) and satellite cells (n=13.5 ± 0.8 cells/10,000 μM2) in the basal turn (immediately inferior to the blue box in Figure 1F) of the non-injected cochlea six weeks after noise exposure as compared to non-sound-damaged controls (n= 18.7 ± 0.6 Type I cells/10,000 μM2, p< 0.01; 20.0 ± 1.6 satellite cells/10,000 μM2, p< 0.01) (Figure 9). However, sound-damaged cochleas injected with cNSCs exhibited a significantly larger density of both Type I spiral ganglion neurons (n=17.0 ± 0.6 cells/10,000 μM2, p< 0.01) and satellite cells (n=14.8 ± 0.9 cells/10,000 μM2, p< 0.01) in the basal turn compared to their non-injected contralateral ears. The cNSC-injected sound-damaged cochleas exhibited a significantly lower concentration of satellite cells in the first cochlear turn than control cochleas (p=0.01). There was no significant difference, however, between the Type I spiral ganglion neurons in injected and normal cochleas (p=0.21). This data indicates that the injection of cNSCs leads to a significant increase in cell density within an average 10,000 μM2 region of the spiral ganglion.

Figure 9. Quantification of spiral ganglion cell counts in the basal turn of the guinea pig cochlea.

Noise damage produced a significant decrease in both Type I spiral ganglion neurons and satellite cells in non-injected ears (N=4). Cochleas that were injected with cNSCs (N=4) exhibited a significant increase in the numbers of Type I spiral ganglion neurons and satellite cells at six weeks compared to their contralateral un-injected cochleas. Asterisk = significantly different from normal controls, diamond = significantly different from non-injected cochleas.

Next, we sought to correlate the increase in cell density of an average 10,000 μM2 region to the entire spiral ganglion region of the transplanted cochlea. Since the method of counting cell density resulted in 1/3 of the total spiral ganglion being counted (Materials and Methods), we multiplied the increase in the spiral ganglion cell number (1.9 cell/10,000 μM2 difference between injected and non injected cochleas) by 3 and added this to the increase in the satellite cell number (1.3 cell/10,000 μM2 difference between injected and non injected cochleas) which was also multiplied by 3. Thus we estimate that the spiral ganglion of each transplanted cochlea exhibits an average increase of 5.7 Type I spiral ganglion neurons and 3.9 satellite cells as compared to non-injected contralateral cochleas.

The noise damage caused a decrease in the average numbers of outer hair cells, pillar cells, and Dieter's cells of the organ of Corti in the second and third cochlear turn (Figure 1). However, the structural damage produced by the noise was highly variable. Therefore, our counts failed to detect a significant change in the numbers of these organ of Corti cells in cochleas injected with cNSCs when compared to non-injected noise exposed animals (data not shown).

Finally, we sought to determine the grafting efficiency of the transplanted cells. In guinea pig, the injections were perfused throughout the perilymphatic duct of the inner ear, the total volume of which is 15.94 μl, and the cochlear potion consists of 8.87 μl (Shinomori et al., 2001). Theoretically, if all the stem cells in suspension were injected into the perilymph, then approximately 354,800 cells were instilled into each cochlea. The data presented on in Figure 9 represents the average count cells/ 100,000 μM2 in 6 μM sections of each turn of the cochlea. To calculate the total number of engrafted cNSCs/cochlea, one needs to multiply the approximately 9.6 cells /section in the basal turn alone (5.7 Type I spiral ganglion neurons + 3.9 satellite cells) by the 50 sections analyzed from each cochlea (Material and Methods). This equates to approximately 480 cells in the basal spiral ganglion per injected cochlea and corresponds to an engraftment efficiency of approximately 0.14%.

We observed cNSC-labeled cells in other regions of the cochlea, including more apical sections of the spiral ganglion and the organ of Corti (Figures 6-8, Tables 2-3). However, these cells failed to represent a statistically significant increase in a particular cell type. If we were to include the total numbers of cNSC-labeled cells observed throughout the entire cochlear spiral ganglion, organ of Corti, and boney labyrinth, there would be on average 13 additional cells per section. This corresponds to approximately 1,130 cells per cochlea, which represents a grafting efficiency of 0.32%.

Discussion

Our results indicate that injection of cNSCs into the scala tympani following noise exposure resulted in markers for cNSCs appearing throughout the structures of the cochlea including Rosenthal's canal and the organ of Corti. We speculate that the appearance of these markers indicates that some of the cNSCs migrated to different areas of the cochlea from the scala tympani. Utilizing morphological, protein expression and genetic criteria, cNSCs were found with characteristics of both neural tissues (satellite, spiral ganglion and Schwann cells) and cells of the organ of Corti (hair cells, supporting cells).

The different expression profiles exhibited by the cNSCs indicate that the cochlear microenvironment exerts an influence over cNSC development. We hypothesize that once the cells of this neural stem cell line migrate within the cochlea, they receive signals from the microenvironment and will upregulate genetic cell fate programs expressed by local endogenous cells. This is consistent with results of cNSC transplantation experiments in both the brain and spinal cord where transplanted cNSCs upregulated the endogenous phenotypes of the surrounding environment (Doering et al., 2000; Himes et al., 2001; Ourednik et al., 2002; Park et al., 2002; Rosario et al., 1997; Snyder et al., 1997; Wagner et al., 1999; Yandava et al., 1999; Yang M, 2002). Once within the microenvironment of the cochlea, some cells upregulate site-specific proteins that correspond to either neural, glial, hair cell or supporting cell types. These results support the developmental potential of stem cells. They also suggest that the mature mammalian cochlea retains the signals necessary to influence stem cell differentiation along a cochlear phenotype, even though it cannot regenerate these cells from its own endogenous population. The timing of cell transplantation also bears mention. Two days post sound damage was chosen for the injection time because preliminary experiments indicated that the number of engrafted cells decreased as the latency between sound damage and stem cell injection increased. We assume that at two days post otic insult, the cochlear environment is in a metabolic state of flux, and as such, the transplanted cells would be exposed to factors not encountered in a healthy cochlea. Nonetheless, different latencies between otic insult and stem cell injections should be systematically investigated in future studies.

For the most part, the exogenous cells exhibited the expression patterns expected from endogenous cells of the local environment to which they migrated. However, there are at least three instances where transplanted cells expressed markers inconsistent with the local microenvironment (Table 3). In murine cochleas, those cells labeled as cNSCs in the pillar region of the organ of Corti adopted the appropriate pillar cell morphology, however these cells expressed the neuronal marker β-III tubulin, which is normally absent in the pillar cells at any age (Jensen-Smith et al., 2003). Similarly, some murine Schwann cells located in the osseous spiral lamia also labeled inappropriately for β-III tubulin. Since β-III tubulin is a marker for immature neurons, it may be that the cNSCs have not completely abandoned all of their neuronal characteristics even though their morphology suggests otherwise. In addition to β-III tubulin, some transplanted cells expressed Myosin 7a in inappropriate environments. As previously noted, hair cells are normally the only cochlear cell type that express myosin 7a. Also, cNSC cells normally express myosin 7a when cultured in differentiating conditions in vitro (Figure 5). In these experiments, the cNSC-derived cells that had localized to the spiral ganglion, spiral ligament and spiral limbus expressed myosin 7a, whereas endogenous cells of these regions fail to express this marker. An explanation of this atypical expression of myosin 7a in cNSC-derived cells could be that the ability for the cNSCs to differentiate completely as a cochlear cell type is limited. Evidence of incomplete differentiation of cNSCs into cochlear cell types can be seen in Figure 6, where a stem cell localized to the spiral ligament expresses a non-cochlear phenotype (white arrow).

Although we did not detect a significant amount of cNSC proliferation (i.e. tumorigenesis) after transplantation, we cannot rule out a limited amount of replication by the transplanted cells. Therefore, it is unknown whether the injected cNSCs themselves or their daughter cells differentiate into the above described cell types. In some in vivo systems, it has been suggested that stem cells up-regulate end organ specific markers not by differentiation, but by fusing with endogenous end organ cells (Ying et al., 2002). One of the advantages of using FISH to detect xeno-transplanted cells is that it may also be used to detect cell fusion (Jiang et al., 2004; Ng et al., 2003; Sato et al., 2005; Vogel, 2004). Although we are unable to completely rule out the possibility of cell fusion in these experiments, we never saw multiple sex chromosomes (i.e. XXXY rather than XX or XY) when we labeled sections with both X and Y specific probes (data not shown). Therefore, based on our observations have do not have convincing evidence that cell fusion has occurred in these experiments. We presented only data that showed Y labeling, because the red channel could then be used to determine expression by immunohistochemistry.

Cochleas that have been transplanted with cNSCs exhibit a significantly greater number of satellite cells and Type I spiral ganglion neurons in the basal turn compared to noise exposed only cochleas. At present, we cannot tell whether this represents newly generated cells or the preservation of cells already present. If they represent newly generated cells the grafting percentage does not represents a staggering number. However, engraftment of 480 cells per turn or 1,130 cells per cochlea is an interesting finding in and of itself, especially when one considers that the injection was not into the modiolus, but into the perilymph.

It is not surprising that neural stem cells differentiate into nervous tissue such as satellite cells and neurons when localized to the spiral ganglion. One of the defining characteristics of a NSC involves the ability to differentiate into a variety of the nervous system cell types. Here we show that NSCs can also differentiate down a pathway that includes the tissues of the cochlear sensory epithelium. Although hair cells are not neurons, they release neurotransmitter(s) upon depolarization, share many transcription factors and proteins expressed in CNS neurons and their association with the nervous system is highlighted by synaptic connections with neurons of both the spiral ganglion and the CNS.

There are precedents for transplanting NSCs into the cochlea. Ito et al. (Ito et al., 2001) have injected aggregates of hippocampal stem cells, or neurospheres, into the cochlear round window of normal rats and described that not only were these aggregates present for up to 4 weeks after transplantation, they had also adopted the “morphology and position of hair cells”. However, they did not report the differentiation of the neurospheres into any non-sensory cells of the cochlea or into any cell types in the spiral ganglion. When considering the neural origin of the neurosphere, it seems unlikely that the sole progeny of transplanted neurospheres would be hair cells. By definition, a neural stem cell would be expected to produce heterogeneous neural progeny such as neurons and glia. Moreover, there was no clear evidence that these neurospheres actually integrated within the sensory epithelium or were capable of full hair cell differentiation as measured by the ability to express hair cell markers such as myosin 7a or oncomodulin.

The results from our study indicate a proof of principle; that cNSCs may be a useful therapeutic tool to repair damaged cochleas. The cNSCs employed in our study integrated into the cochlear tissue and differentiated into a variety of cochlear cell types. Thus, they may be able to replace many of the cell types damaged by trauma. For instance, a form of auditory neuropathy is apparently associated with a loss of myelinating cells of the cochlea (Berlin et al., 2003); therefore, the therapeutic potential of neural stem cells in this disease should be explored. In addition, the ability of these NSCs to differentiate preferentially into specific cell types, such as hair cells, should be pursued. Finally, these studies should be repeated by using other types of stem cells to test whether or not embryonic or hematopoietic stem cells could produce equivalent or even better results than the NSCs. Moreover, one study has reported that the vestibular system may contain a population of endogenous stem cells that can differentiate into a number of cell and tissue types (Li et al., 2003). It is possible that the isolation and transplantation of these cochlear stem cells would prove even more suitable than cNSCs for cochlear repair.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the laboratory efforts of Luke Wall, Niloy Roy and Ronald Ahlfeldt as well as the editorial skills of Jennifer Pina. This work was supported by a Hair Cell Regeneration Initiative Grant from the NOHR Foundation, an NRSA F32 Fellowship DC05866-02 (M.A.P.), a grant from the Dosberg Foundation, The Sarah Fuller Fund, and by an anonymous donation to the Laboratory for Cellular and Molecular Hearing Research at Children's Hospital.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Berlin CI, Morlet T, Hood LJ. Auditory neuropathy/dyssynchrony: its diagnosis and management. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2003;50:331–40. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(03)00031-2. vii-viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobbin RP, Parker M, Wall L. Thapsigargin suppresses cochlear potentials and DPOAEs and is toxic to hair cells. Hear Res. 2003;184:51–60. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(03)00230-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corwin JT, Cotanche DA. Regeneration of sensory hair cells after acoustic trauma. Science. 1988;240:1772–4. doi: 10.1126/science.3381100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Andrea P, Veronesi V, Bicego M, Melchionda S, Zelante L, Di Iorio E, Bruzzone R, Gasparini P. Hearing loss: frequency and functional studies of the most common connexin26 alleles. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;296:685–91. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)00891-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deb A, Wang S, Skelding KA, Miller D, Simper D, Caplice NM. Bone Marrow-Derived Cardiomyocytes Are Present in Adult Human Heart: A Study of Gender-Mismatched Bone Marrow Transplantation Patients. Circulation. 2003;107:1247–1249. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000061910.39145.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doering LC, Snyder EY. Cholinergic expression by a neural stem cell line grafted to the adult medial septum/diagonal band complex. J Neurosci Res. 2000;61:597–604. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20000915)61:6<597::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glastonbury C, Davidson H, Harnsberger H, Butler J, Kertesz T, Shelton C. Imaging findings of cochlear nerve deficiency. Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23:635–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasko JA, Richardson GP, Russell IJ, Shaw G. Transient expression of neurofilament protein during hair cell development in the mouse cochlea. Hear Res. 1990;45:63–67. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(90)90183-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himes BT, Liu Y, Solowska JM, Snyder EY, Fischer I, Tessler A. Transplants of cells genetically modified to express neurotrophin-3 rescue axotomized Clarke's nucleus neurons after spinal cord hemisection in adult rats. J Neurosci Res. 2001;65:549–64. doi: 10.1002/jnr.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holley MC. Application of new biological approaches to stimulate sensory repair and protection. Br Med Bull. 2002;63:157–69. doi: 10.1093/bmb/63.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail M, Gibson FM, Marks K, Draycott GS, Gordon-Smith EC, Rutherford TR. Combined immunocytochemistry and FISH: an improved method to study engraftment of accessory bone marrow stromal cells. Clin Lab Haematol. 2002;24:329–335. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2257.2002.00463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito J, Kojima K, Kawaguchi S. Survival of Neural Stem Cells in the Cochlea. Acta Otolaryngol. 2001;121:140–42. doi: 10.1080/000164801300043226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumikawa M, Minoda R, Kawamoto K, Abrashkin KA, Swiderski DL, Dolan DF, Brough DE, Raphael Y. Auditory hair cell replacement and hearing improvement by Atoh1 gene therapy in deaf mammals. Nature Medicine. 2005;11:271–276. doi: 10.1038/nm1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen-Smith HC, Eley J, Steyger PS, Luduena RF, Hallworth R. Cell type-specific reduction of beta tubulin isotypes synthesized in the developing gerbil organ of Corti. J Neurocytol. 2003;32:185–7. doi: 10.1023/b:neur.0000005602.18713.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S, Walker L, Afentoulis M, Anderson DA, Jauron-Mills L, Corless CL, Fleming WH. Transplanted human bone marrow contributes to vascular endothelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:16891–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404398101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanzaki S, Kawamoto K, Oh SH, Stover T, Suzuki M, Ishimoto S, Yagi M, Miller JM, Lomax M, Raphael Y. From gene identification to gene therapy. Audiol Neurootol. 2002;7:161–4. doi: 10.1159/000058303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto K, Ishimoto S-I, Minoda R, Brough DE, Raphael Y. Vivo J, editor. Math1 Gene Transfer Generates New Cochlear Hair Cells in Mature Guinea Pigs. Neurosci. 2003;23:4395–4400. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-11-04395.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Liu H, Heller S. Pluripotent stem cells from the adult mouse inner ear. Nature Medicine. 2003;9:1293–9. doi: 10.1038/nm925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi R, Luo Y, Cai J, Limke TL, Rao MS, Höke A. Immortalized neural stem cells differ from nonimmortalized cortical neurospheres and cerebellar granule cell progenitors. Exp Neurol. 2005;194:301–19. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng IO, Chan KL, Shek WH, Lee JM, Fong DY, Lo CM, Fan ST. High frequency of chimerism in transplanted livers. Hepatology. 2003;38:989–998. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ourednik J, Ourednik V, Lynch WP, Schachner M, Snyder EY. Neural stem cells display an inherent mechanism for rescuing dysfunctional neurons. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:1103–10. doi: 10.1038/nbt750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park KI, Teng YD, Snyder EY. The injured brain interacts reciprocally with neural stem cells supported by scaffolds to reconstitute lost tissue. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:111–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker MA, Cotanche DA. The potential use of stem cells for cochlear repair. Audol Neurootol. 2004;9:72–80. doi: 10.1159/000075998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker MA, Anderson JK, Corliss DA, Abraria VE, Sidman RL, Park KI, Teng Y, Cotanche DA, Snyder EY. Expression Profile of an Operationally-Defined Neural Stem Cell Clone. Exp Neurol. 2005;194:320–32. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rio C, Dikkes P, Liberman MC, Corfas G. Glial fibrillary acidic protein expression and promoter activity in the inner ear of developing and adult mice. Journal of Comparitive Neurology. 2002;442:156–62. doi: 10.1002/cne.10085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivolta MN, Grix N, Lawlor P, Ashmore JF, Jagger DJ, Holley MC. Auditory hair cell precursors immortalized from the mammalian inner ear. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1998;265:1595–603. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1998.0477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario C, Yandava B, Kosaras B, Zurakowski D, Sidman R, Snyder E. Differentiation of engrafted multipotent neural progenitors towards replacement of missing granule neurons in meander tail cerebellum may help determine the locus of mutant gene action. Dev. 1997;124:4213–4224. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.21.4213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubel EW, Dew LA, Roberson DW. Mammalian vestibular hair cell regeneration. Science. 1995;267:701–03. doi: 10.1126/science.7839150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryals BM, Rubel EW. Hair cell regeneration after acoustic trauma in adult Coturnix quail. Science. 1988;240:1774–6. doi: 10.1126/science.3381101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi N, Henz l.M.T., Thalmann I, Thalmann R, Schulte BA. Oncomodulin is expressed exclusively by outer hair cells in the organ of Corti. J Histochem Cytochem. 1998;46:29–40. doi: 10.1177/002215549804600105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y, Araki H, Kato J, Nakamura K, Kawano Y, Kobune M, Sato Y, Miyanishi K, Takayama T, Takahashi M, Takimoto R, Iyama S, Matsunaga T, Ohtani S, Matsuura A, Hamada H, Niitsu Y. Human mesenchymal stem cells xenografted directly to rat liver are differentiated into human hepatocytes without fusion. Blood. 2005;106:756–763. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinomori Y, Spack DS, Jones DD, Kimura RS. Volumetric and dimensional analysis of the guinea pig inner ear Ann. The Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology. 2001;110:91–98. doi: 10.1177/000348940111000117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder EY, Yoon C, Flax JD, Macklis JD. Multipotent neural precursors can differentiate toward replacement of neurons undergoing targeted apoptotic degeneration in adult mouse neocortex. PNAS. 1997;94:11663–11668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder EY, Deitcher DL, Walsh C, Arnold-Aldea S, Hartwieg EA, Cepko CL. Multipotent neural cell lines can engraft and participate in development of mouse cerebellum. Cell. 1992;68:33–51. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90204-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng YD, Lavik EB, Qu X, Park KI, Ourednik J, Zurakowski D, Langer R, Snyder EY. Functional recovery following traumatic spinal cord injury mediated by a unique polymer scaffold seeded with neural stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:3024–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052678899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trautwein P, Sininger Y, Nelson R. Cochlear implantation of auditory neuropathy. J Am Acad Audiol. 2000;11:309–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel G. Developmental biology. More data but no answers on powers of adult stem cells. Science. 2004;305:27. doi: 10.1126/science.305.5680.27a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner J, Akerud P, Castro DS, Holm PC, Canals JM, Snyder EY, Perlmann T, Arenas E. Induction of a midbrain dopaminergic phenotype in Nurr1-overexpressing neural stem cells by type 1 astrocytes. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:653–9. doi: 10.1038/10862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Hirose K, Liberman MC. Dynamics of noise-induced cellular injury and repair in the mouse cochlea. JARO. 2002;3:248–68. doi: 10.1007/s101620020028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warchol ME, Lambert PR, Goldstein BJ, Forge A, Corwin JT. Regenerative proliferation in inner ear sensory epithelia from adult guinea pigs and humans. Science. 1993;259:1619–22. doi: 10.1126/science.8456285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weimann JM, Charlton CA, Brazelton TR, Hackman RC, HM. B. Contribution of transplanted bone marrow cells to Purkinje neurons in human adult brains. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2003;100:2088–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337659100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yandava BD, Billinghurst LL, Snyder EY. “Global” cell replacement is feasible via neural stem cell transplantation: Evidence from the dysmyelinated shiverer mouse brain. PNAS. 1999;96:7029–7034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.7029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M SN, Berk MA, Snyder EY, Iacovitti L. Neural stem cells spontaneously express dopaminergic traits after transplantation into the intact or 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rat. Experemental Neurology. 2002;177:50–60. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying QL, Nichols J, Evans EP, Smith AG. Changing potency by spontaneous fusion. Nature. 2002;416:545–8. doi: 10.1038/nature729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]