Abstract

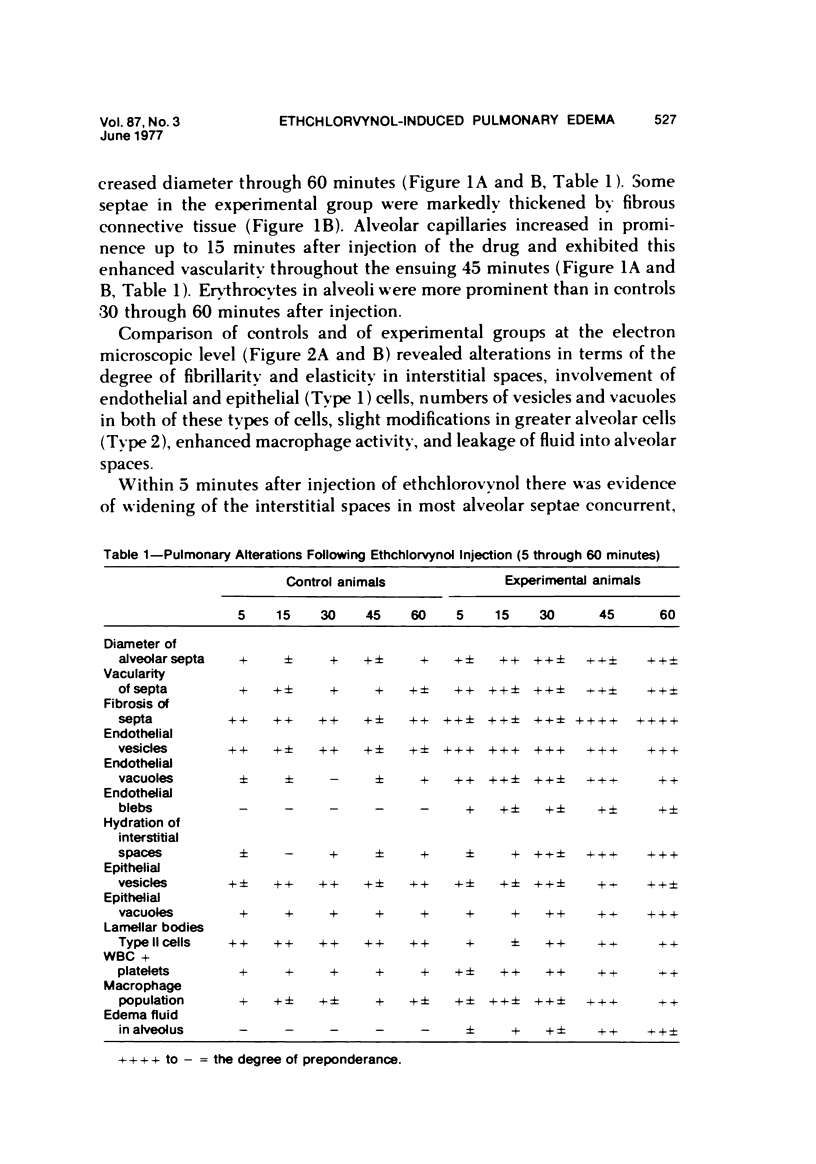

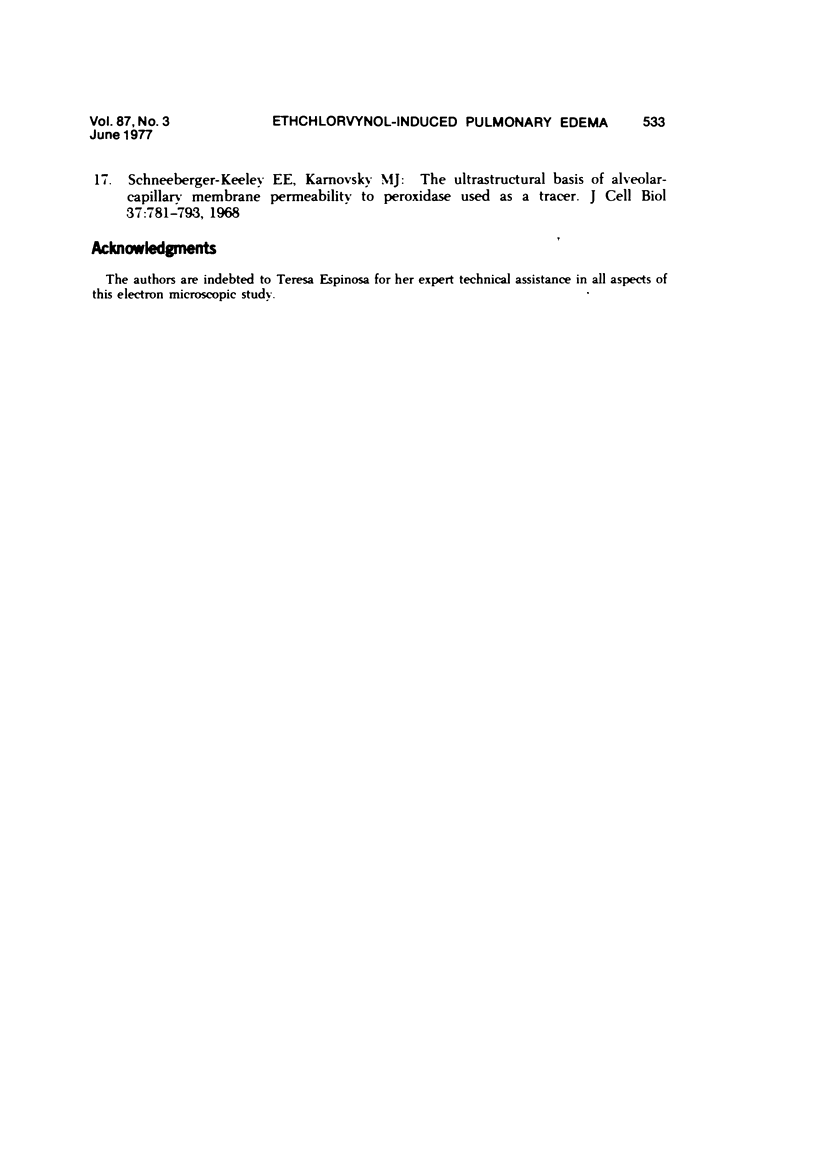

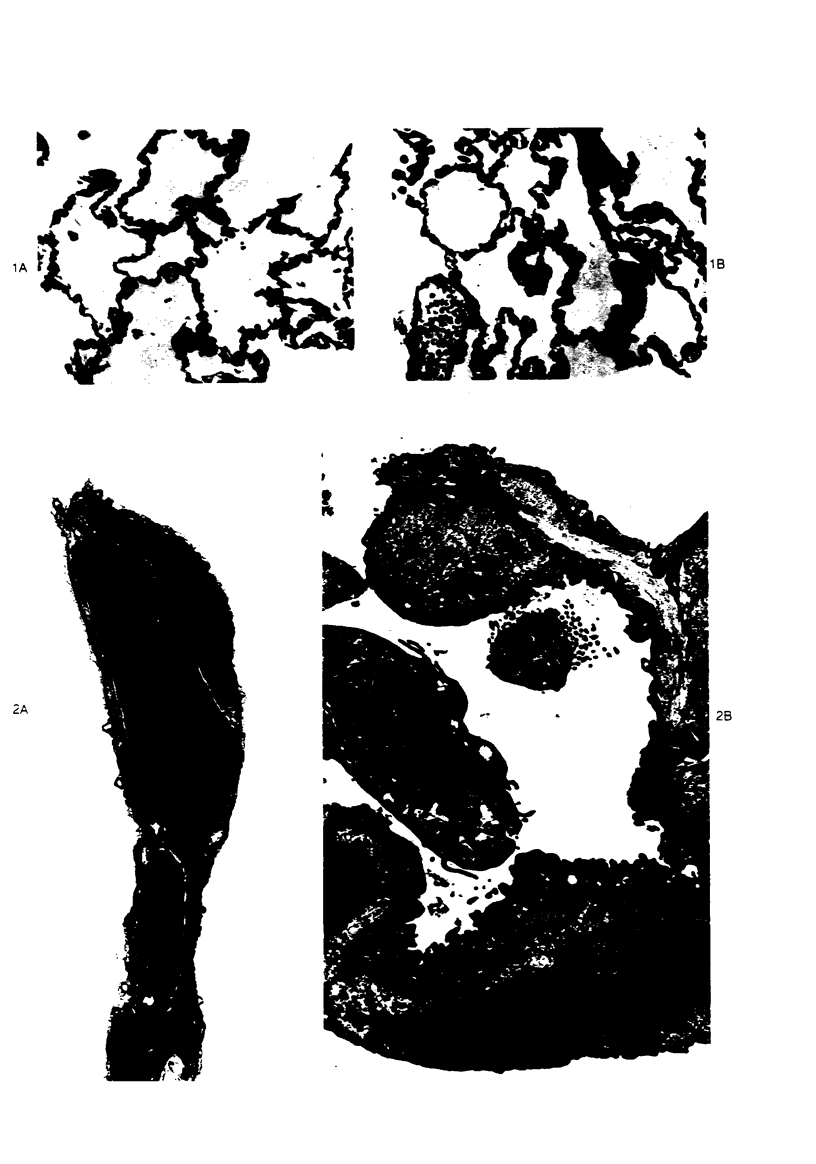

The ultrastructure of alveolar septae in dogs is investigated at times ranging from 30 seconds to 60 minutes after intravenous injection of ethchlorvynol (Placidyl). Pulmonary edematous fluid first appears in alveolar spaces 5 minutes after injection and becomes progressively more prominent with increasing time. Alveolar septae are initially somewhat fibrotic, and subsequently, most interstitial spaces become swollen and hydrated. Vesicles in endothelial cells increase with postinjectional time, and they seem to form channels or pores interconnecting capillaries and interstitial spaces. Similar vesicles in epithelial cells (Type 1) show an increase after 30 minutes, and they also seem to form channels or pores interconnecting interstitial spaces and the alveolus. Vesicles, whether in endothelial or epithelial cells, contain a flocculent filamentous material similar to plasma protein and the filamentous proteinaceous material in edematous fluid in alveolar spaces. Ethchlorvynol injection rapidly induces a non-hemodynamic form of pulmonary edema. Since cell junctions of both endothelial and epithelial cells remained intact, it is proposed that transalveolar transport of edematous proteinaceous fluid is mediated by means of endothelial and epithelial vesicles.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- ALGERI E. J., KATSAS G. G., LUONGO M. A. Determination of ethchlorvynol in biologic mediums, and report of two fatal cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1962 Aug;38:125–130. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/38.2.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell T. S., Levine O. R., Senior R. M., Wiener J., Spiro D., Fishman A. P. Electron microscopic alterations at the alveolar level in pulmonary edema. Circ Res. 1967 Dec;21(6):783–797. doi: 10.1161/01.res.21.6.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frand U. I., Shim C. S., Williams M. H., Jr Heroin-induced pulmonary edema. Sequential studies of pulmonary function. Ann Intern Med. 1972 Jul;77(1):29–35. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-77-1-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glauser F. L., Smith W. R., Caldwell A., Hoshiko M., Dolan G. S., Baer H., Olsher N. Ethchlorvynol (Placidyl)-induced pulmonary edema. Ann Intern Med. 1976 Jan;84(1):46–48. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-84-1-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes J. A., Shiga A. Ultrastructural changes in pulmonary oedema produced experimentally with ammonium sulphate. J Pathol. 1970 Apr;100(4):281–286. doi: 10.1002/path.1711000407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath D., Moosavi H., Smith P. Ultrastructure of high altitude pulmonary oedema. Thorax. 1973 Nov;28(6):694–700. doi: 10.1136/thx.28.6.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnovsky M. J. The ultrastructural basis of capillary permeability studied with peroxidase as a tracer. J Cell Biol. 1967 Oct;35(1):213–236. doi: 10.1083/jcb.35.1.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyrick B., Miller J., Reid L. Pulmonary oedema induced by ANTU, or by high or low oxygen concentrations in rat--an electron microscopic study. Br J Exp Pathol. 1972 Aug;53(4):347–358. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneeberger-Keeley E. E., Karnovsky M. J. The ultrastructural basis of alveolar-capillary membrane permeability to peroxidase used as a tracer. J Cell Biol. 1968 Jun;37(3):781–793. doi: 10.1083/jcb.37.3.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simionescu N., Palade G. E. Dextrans and glycogens as particulate tracers for studying capillary permeability. J Cell Biol. 1971 Sep;50(3):616–624. doi: 10.1083/jcb.50.3.616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simionescu N., Siminoescu M., Palade G. E. Permeability of muscle capillaries to small heme-peptides. Evidence for the existence of patent transendothelial channels. J Cell Biol. 1975 Mar;64(3):586–607. doi: 10.1083/jcb.64.3.586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staub N. C., Nagano H., Pearce M. L. Pulmonary edema in dogs, especially the sequence of fluid accumulation in lungs. J Appl Physiol. 1967 Feb;22(2):227–240. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1967.22.2.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg A. D., Karliner J. S. The clinical spectrum of heroin pulmonary edema. Arch Intern Med. 1968 Aug;122(2):122–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szidon J. P., Pietra G. G., Fishman A. P. The alveolar-capillary membrane and pulmonary edema. N Engl J Med. 1972 Jun 1;286(22):1200–1204. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197206012862208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplitz C. The ultrastructural basis for pulmonary pathophysiology following trauma. Pathogenesis of pulmonary edema. J Trauma. 1968 Sep;8(5):700–714. doi: 10.1097/00005373-196809000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodore J., Robin E. D., Gaudio R., Acevedo J. Transalveolar transport of large polar solutes (sucrose, inulin, and dextran). Am J Physiol. 1975 Oct;229(4):989–996. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1975.229.4.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]