Abstract

Background

Headache accounts for up to a third of new specialist neurology appointments, although brain lesions are extremely rare and there is little difference in clinical severity of referred patients and those managed in primary care. This study examines influences on GPs' referral for headache in the absence of clinical indicators.

Design of study

Qualitative interview study.

Setting

Eighteen urban and suburban general practices in the South Thames area, London.

Method

Purposive sample comprising GPs with varying numbers of referrals for headache over a 12-month period. Semi-structured interviews with 20 GPs were audio taped. Transcripts were analysed thematically using a framework approach.

Results

All GPs reported observing patient anxiety and experiencing pressure for referral. Readiness to refer in response to pressure was influenced by characteristics of the consultation, including frequent attendance, communication problems and time constraints. GPs' accounts showed variations in individual's willingness or ‘resistance’ to refer, reflecting differences in clinical confidence in identifying risks of brain tumour, personal tolerance of uncertainty, views of patients' ‘right’ to referral and perceptions of the therapeutic value of referral. A further source of variation was the local availability of services, including GPs with a specialist interest and charitably-funded clinics.

Conclusion

Referral for headache is often the outcome of patient pressure interacting with GP characteristics, organisational factors and service availability. Reducing specialist neurological referrals requires further training and support for some GPs in the diagnosis and management of headache. To reduce clinical uncertainty, good clinical prediction rules for headache and alternative referral pathways are required.

Keywords: doctor–patient relationship, headache, patient anxiety, referral, qualitative

INTRODUCTION

Headache, including migraine, accounts for 44 consultations per 1000 people in primary care,1 even though much headache is self-managed and not presented to doctors.2 Some life-threatening brain disorders present with secondary headache, but this is extremely rare and accounts for less than 0.1% of the population who experience headaches.3 Most headaches in the community are due to primary headache where the headache itself is the disorder, such as tension headache, migraine and chronic daily headache. However, large numbers of headache sufferers managed in primary care do not receive a specific diagnosis and are diagnosed as ‘headache not otherwise specified’.4 Brain imaging, although essential for the optimal management of brain tumours and other secondary headache disorders, is not recommended for the clinical management of most headaches.5

GPs refer 2–3% of patients consulting for headaches.1 This forms the most common symptom presented to neurologists and accounts for up to a third of new specialist neurology appointments6 in the UK. A study compared adult patients presenting with headache (including migraine) who were managed by GPs with patients referred to neurologists. Results indicated that the referred group did not experience greater impact or disability because of their headaches and were not clinically more severely affected,7 raising questions of the reasons and needs for specialist referral. This is of particular importance in the UK where access to neurologists is scarce and where the neurology workforce is one-tenth the size of other western countries.8 Therefore, small changes in referral patterns can have large effects on capacity in the UK.

How this fits in

The large numbers of patients referred to neurology services for headache and apparent variations in GP referral rates cannot be explained by the severity of headache. This paper identifies the importance of GPs' perceptions of patient anxiety and pressure in shaping referral decisions, especially when accompanied by time pressures and problems in the doctor-patient relationship. GPs' willingness to refer is also influenced by their clinical confidence and worries about missed diagnosis, personal tolerance of uncertainty, views of patients' ‘right’ to referral, and belief in the therapeutic value of referral. Situational factors increasing readiness to refer include the local availability of sources of referral.

There is evidence of variation between GPs' referral rates of patients with headache to a neurologist. Referrals of 150 GPs in 18 practices in South Thames were analysed. Over a 1-year period 63% made no headache referrals, 33% made one or two referrals and 4% made three or more referrals.7 In view of the small numbers of referrals it is difficult to know if this represents true differences in referral practices. These results correspond with well-documented variations in overall general practice referral rates that are not accounted for by random variation, other statistical artefacts, or by differences in age, sex, and morbidity of practice populations.9–11 A large number of mainly quantitative studies have sought to identify factors associated with differences in referral rates. No consistent pattern has emerged and it has been concluded that, ‘variation in referral rates remains largely unexplained’.10

To date there has been only a small number of qualitative studies of GPs' referral behaviour and none relating specifically to headache. This paper reports findings of a study that aimed to elicit GPs' beliefs about and motives for the referral of adult patients with primary headache. It employs qualitative methods to allow more detailed exploration of GPs' personal beliefs and reasons for referral behaviours than is possible using more structured approaches.

METHOD

A purposive sample of 40 GPs was selected from the larger database of 150 GPs in the South Thames region. The researchers approached all seven GPs referring three or more patients in 1 year. GPs who made one or two referrals over this period were selected and GPs who made no referrals were selected according to those with the highest number of headache patients during the study period.

A non-medical researcher conducted semi-structured interviews with the study sample. Interviews were based on a topic guide that was informed by prior literature and three preliminary interviews (Box 1). GPs were encouraged to talk freely, with the interviewer probing and prompting responses as required. Interviews were held at the practice and were all tape-recorded with permission. The majority of interviews lasted 30–45 minutes (range = 20–60 minutes). By the time 20 interviews had been conducted, responses indicated that the saturation point had been reached and it was therefore not necessary to contact further GPs.

Box 1. Research topic guide.

GPs were asked about their management of and approach to the diagnosis of patients presenting with headache and migraine. The main themes with examples of prompts are given below:

-

▸

Can you tell me about the headaches you see?

What types, how common?

-

▸

What happens when someone presents with headache or migraine — how do you decide how to manage the problem?

What are the options, what do you prefer to do, what do you usually do, how do you treat?

-

▸

Do any particular characteristics of the patient influence this?

Duration of headache, patients age/sex, frequency of attendance, knowledge, expressed views and wishes.

-

▸

How do your own qualities influence the decision to refer?

Training and experience, skills, attitude to risk, management of uncertainty, relationship with hospital consultants.

-

▸

What are your views of the barriers to referral and the benefits?

Availability of services, waiting times, practice referral guidance, perceived benefit of referral, effect of private insurance.

Interviews were fully transcribed. A preliminary coding scheme was developed and tested by the three authors coding independently. Points of difference were discussed and revisions made until a common approach was agreed. The coded transcripts were analysed using ATLAS-ti qualitative analysis software. Initially, the main coding categories were analysed. The coded segments were then charted using a framework approach. Relationships between the variables were identified by examining responses given by individual GPs to a series of questions relating to a particular theme.12

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

Forty GPs were approached. Two refused to be interviewed, 13 had left the practice and five were unavailable due to maternity leave, sick leave or annual leave. The 20 responders were from six inner and seven outer London practices and included areas ranging from deprived inner London to affluent suburban areas. Eleven GPs were men and nine were women. Mean age was 42.3 (SD = 8.6) years (male = 40.8 years and female = 43.5 years). Ten study GPs made no referrals for headache in the past year, five GPs made one or two referrals, and five GPs made three referrals.

Patient anxiety and pressure

All GPs described problems of patient anxiety and pressure for referral for headache, mainly because of fear of a brain tumour:

‘ … everybody feels they need a scan — as soon as they've got a headache they feel they need a CT scan, or they've heard of the scan and think that's the only way of knowing what's going on in their head … and sometimes as a GP, you know, you're pressed to send patients for their investigations.’ (GP 5208)

All GPs acknowledged that they had made referrals in situations where they were unable to convince patients that there was no organic cause. Such referrals were most likely if the patient was a frequent consulter and their headache was of considerable duration:

‘ … ultimately they say that's all very interesting and thank you very much for the time you've taken, but I still want to see someone …’ (GP 0604)

GPs also acknowledged that problems in the doctor–patient relationship and time pressures increased their readiness to refer as a way of managing the consultation:

‘ … say you were supposed to have a 10-minute appointment but you've already been in here for 20 minutes and I'm beginning to get a bit hot and bothered and I realise that your agenda is to get a referral, then its highly tempting not to debate anymore, because you think, well if I say ‘yes’ to that, then … they'll be happier and they'll go, and I'll be happier …’ (GP 1803)

All GPs acknowledged referring in response to patient pressure, especially as a way of managing the consultation. However, GPs' accounts identified differences in their willingness or ‘resistance’ to refer. Willingness to refer was influenced by clinical confidence, ability to tolerate uncertainty, attitudes and beliefs regarding referral, and by the local availability of services.

Clinical confidence

A key characteristic influencing GPs' attitudes to referral was their clinical confidence in conducting neurological examinations, including checking the fundi for papilloedema to identify ‘red flags’ for headache that should trigger a search for secondary headache.6 GPs who described themselves as very confident in conducting a brief neurological examination, appeared to resist patient pressures most strongly. These GPs questioned the appropriateness of referral when they felt confident that this was not clinically necessary:

‘I'm quite resistant if I think there's no [clinical] concern … to a patient bullying me into referring them. Partly with one eye to resources and how few neurologists there are in the country and how important those appointments are … partly with a view to not being willing to feed into that consumerism and actually because, actually you know, it feeds into that anxiety as well and that pattern of behaviour that I'll get a second opinion for every single problem I ever have. So I'm quite resistant to patients requesting reassurance for problems which I feel I could reassure them … but occasionally I have done it.’ (GP2510)

The majority of GPs, although confident in their ability to identify indicators for secondary headache, achieved this by taking an accurate history and asking discerning questions. They described themselves as feeling less certain about conducting a brief neurological examination:

‘I'm not sure I'd definitely pick up papilloedema looking at the back of the eye, ‘cos I'm not sure if I've ever seen it … but to be honest I think by the time you're diagnosing a brain tumour by finding papilloedema you've got a pretty clear history and picture of what you're going to be looking for.’ (GP 1707)

GPs often described tests as important in reassuring patients rather than a necessary requirement for diagnosis. They frequently referred to the ‘safety net’ of bringing patients back for review to check what was happening and giving patients a ‘licence’ to come back. Rather than emphasising the importance of tests in reassuring patients, they described the importance of their experience and their rapport and relationships with patients:

‘I think part of my ability to help people is [a] projection of my confidence, personality, holistic approach, whatever … to give them confidence in me so when I say: “it's fine” they believe me.’ (GP 1704)

A small number of GPs acknowledged that they lacked confidence in diagnosing headache and were therefore the most willing to refer. For two GPs this was because they or their partner had previously missed diagnosing a brain tumour. Others recognised their limited clinical experience or the need to ‘brush up’ their diagnostic examination skills for headache:

‘If someone says to me they've got a headache I kind of like … I do take a deep breath. I'll be honest with you, its not my favourite subject … and its only through experience that one feels more confident dealing with headache.’ (GP 2511)

A few inner-city GPs observed that they were more likely to refer patients with poorer English from a different cultural background, as they felt less confident in assessing the severity of headache experienced by these patients.

Some GPs commented that (and others were asked directly), if referral for headache was influenced by worries about patient complaints. This was of particular significance for two GPs aware of a missed diagnosis of a brain tumour. However, the general response was to acknowledge that this influence was something ‘in the back of my mind’:

‘It's not at the forefront … its always at the back of my mind to some extent but I think I've been able to deal with it in my own mind enough not to let it affect my clinical judgement … I'd find it very difficult to practice if I had to do things because I felt they were going to sue me … I think I've managed to negotiate in my brain a way of dealing with it by being conscious of it but not letting it affect me.’ (GP 5303)

GPs' responses appeared to reflect their practice style, either emphasising the importance of tests to rule out red flags or stressing the importance of ‘working with the patient’ and communication to explain what you are doing.

Tolerance of uncertainty

Some GPs described considerable personal cautiousness and inability to tolerate uncertainty. These GPs acknowledged that they referred for their own reassurance:

‘I'm, I would say, cautious I suppose. I tend to err on the side of caution and refer more … that's my nature.’ (GP 0607)

This was particularly, but not exclusively, emphasised by GPs who described less clinical confidence:

‘ … I might refer people just for my own anxiety and fears of missing something, even if they're not anxious. So, really, I suppose it depends on lots of factors.’ (GP 1803)

‘If we could refer everybody for an MRI scan tomorrow, we'd all have a lot more peace of mind. But we cannot, because there aren't the facilities available. And so we have to live with uncertainty and we can, all of us, can only live with a certain amount — there comes a point where you just get uneasy and think “I need to be more sure about this”.’ (GP 2511)

However, problems of tolerating uncertainty were not fully explained by actual clinical competence or experience, as this GP observed:

‘We used to have a partner who is retired now who had pretty well double everyone else's [referral rate], in spite of being very experienced, good at diagnosis and so on, but he couldn't stand uncertainty.’ (GP3911)

Beliefs and attitudes to referral

‘Right’ to referral

GPs who were most resistant to pressures for referral in the absence of clinical indicators often extended this to requests for a private referral:

‘ … even if someone was asking for a private referral and was prepared to pay for it, I don't think I would refer something that I felt was not appropriate, simply because they were anxious about it … Sometimes, if they are anxious and its affecting their ability to deal with the problem then, you know, you may need to investigate further just for reassurance.’ (GP 1704)

In contrast, the majority of GPs acknowledged what they described as patients' ‘right’ to a referral and some therefore agreed fairly readily to patients' requests:

‘My view is, if it was in any other Western country people would be getting these things [referral], so why should they be denied in this country … ’ (GP 0710)

These GPs often regarded it beneficial for both themselves and patients to agree to requests for referral at an early stage:

‘If you pick up that the only thing that's really going to make them happy that they haven't got something awful is to have a scan, then there probably isn't a lot of point to bring them both back several times and try to persuade them that it's not the case.’ (GP 0604)

Therapeutic value

Whereas some GPs regarded referral for reassurance as inappropriate in the absence of clinical indicators, many GPs justified referral for its therapeutic effects in reducing patients' anxiety and helping them cope:

‘For some people we could actually have a cardboard CT scanner, and because it's the scan that's therapeutic. Although having said that, it is reassuring to me, even though I'm pretty sure they've got a tension headache … but it doesn't always work [for patients] …’ (GP 1304)

Referral was also identified as assisting doctor and patient in working together:

‘ … once you've got the brain scan out of the way, then you're on an equal footing and basically neither of you know exactly the best way to go and you can sort of muddle along together.’ (GP 0710)

Alternative sources of advice and referral

The local availability of alternative facilities increased GPs' readiness to refer. For example, two GPs acknowledged that they referred more readily to a GP with Special Interest (GPwSI) who, if required, could organise a scan more quickly. Four GPs made referrals to a regional charitably-funded clinic for migraine and tension headaches, describing this as an important ‘back-stop’ with considerably shorter waiting times compared with a neurology specialist referral:

‘The ones who go to the headache clinic are usually ones where you think it's probably going to be alright, but you're not so confident that you can just turn them away, but they're not showing signs of particularly neurological … abnormality or anything …’ (GP 1704)

Some GPs also sought advice or made referrals in ways that are not formally recorded as referral. This included referring to a GPwSI within the practice, asking advice on the phone from the consultant neurologist or clinic, and referral to a physiotherapist or acupuncturist for treatment. One GP commented positively on having direct access to a scan, although several GPs observed that they did not want direct access to scans unless this involved a neurologist's report.

DISCUSSION

Summary of main findings

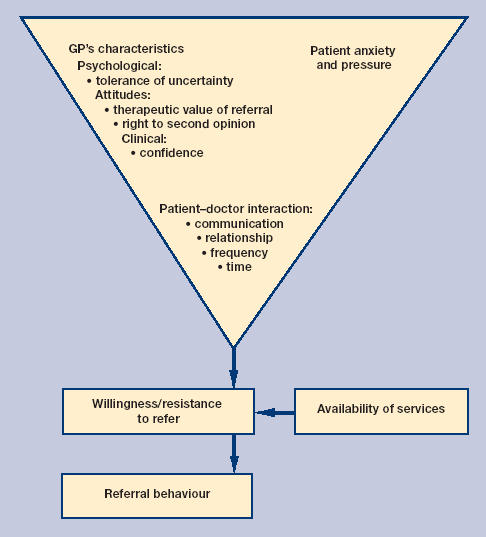

GPs' accounts identified the perceived importance of patient anxiety and pressure in making referrals for headache in the absence of clinical indications. All GPs acknowledged that they had made referrals for headache in response to patient pressure, especially for patients whose headache was of long duration and who were frequent consulters, or as a way of managing a difficult consultation. There was also evidence of individual differences in GPs' willingness or ‘resistance’ to refer. Resistance was associated with confidence in conducting basic neurological checks, personal tolerance of uncertainty, and questioning patients' ‘right’ to referral and its therapeutic value. The local availability of services was also an important determinant of referral practices and responses to patient pressure (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Major influences on GPs' referral behaviour for headache in the absence of clinical indicators.

A comparison of GPs' accounts with recorded numbers of patients referred for headache over a 1-year period, indicated that making no referral over the recording period was associated with high clinical confidence and questioning of patients' right to referral. However, there was not a complete correspondence, which may reflect the problem of small numbers as well as variations in practice populations (the study included relatively affluent and disadvantaged areas). Research on other medical conditions suggests that younger people with a relatively high education and expectations of patients' rights and choices may press for referral at an earlier stage compared with older and more disadvantaged populations, or GPs be more willing to refer them.13

GPs' accounts also identified the interaction between variables. For example, some GPs who were clinically confident questioned the appropriateness and therapeutic value of referral, had a low personal tolerance of uncertainty, and practised in areas with alternative sources of referral.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The GP study group was drawn from practices in deprived urban areas and more affluent suburban practices, and GPs with a range of referral rates were selected. This diversity aimed to identify the range of views and GP behaviours that can occur in different settings. A non-medical researcher conducted the interviews in an informal conversational manner. The rapport she achieved with GPs in discussing their worries and uncertainties in managing headache indicated that the accounts they provided reflected their personal beliefs and practices rather forming an acceptable ‘public’ account.

A limitation was the focus solely on GPs' reporting rather than direct observation of consultations or eliciting patients' wishes and views of the consultation. Although all GPs identified issues of patient pressure for referral, it was not possible to establish whether GPs varied in their perception of patient pressure. Pressure is conveyed not only by direct requests for referral but also by the ways in which patients present the impact of symptoms, including their use of emotional language and expression of emotional distress.14

How GPs actually perceive patient anxiety and pressure, and also whether patient pressure is reduced if GPs are more confident and conduct basic neurological examinations, requires further study. Although GPs talked about patients' ‘right’ to referral, it is not clear whether patients also regarded referral as a ‘right’ or if they referred to this in the consultation.

Comparison with existing literature

GPs' perceptions of considerable anxiety among many patients presenting with headache is corroborated by patient-based accounts15 and has been identified as an influence on referral for a wide range of conditions.14,16–17 The model derived in this study, although concerned specifically with explaining variations in referral for headache, is likely to be applicable to other conditions for which patients press for referral to achieve a definitive investigation, such as patients with low-back pain wanting a lumbar spine scan and patients with dyspepsia wanting to have a gastroscopy for diagnostic purposes. There is also evidence that patient pressure combined with doctors' personal readiness to serve; feelings of insecurity and uncertainty are not restricted to referral and are also a strong independent predictor of prescribing in the absence of clear clinical indications, such as prescribing of antidepressants and antibiotics.18,19 An outcome of these influences on GPs' behaviours is that a significant minority of examining, prescribing, and referral behaviour and almost half of investigations are thought by GPs to be slightly needed or not needed at all.20

Implications for clinical practice

Current policies that emphasise consumer choice may increase pressures to refer.21 This identifies the importance of doctors asking patients directly about their expectations and worries, and the need to assist GPs in managing their patients' and their own uncertainty. This forms a particular challenge in primary care, as GPs generally deal with greater diagnostic uncertainty than their hospital-based colleagues. The development of validated clinical prediction rules based on systematic reviews and original research have been advocated as progress toward achieving rational and evidence-based test-ordering and referral through quantifying individual contributions that history, examination and basic tests make towards a diagnosis.22 For example, good clinical prediction rules with high predictive values for excluding brain tumour as a diagnosis could reduce uncertainty in the management of headache and enhance GPs' confidence.

Management of headache requires not only confidence in diagnosis but also reassuring patients who worry that they may have a serious condition. There is some evidence that patients with a high level of psychological morbidity who receive a scan have reduced service use for headache; the provision of a scan may therefore be cost-effective for this group.23 However, two studies examining the effects of referral for headache on clinical outcomes, assessed in terms of symptoms and patient anxiety, produced conflicting findings.15,23 Inconclusive results may reflect differences in the processes of care, particularly the quality of communication and reassurance given by the clinician which may sometimes be of greater importance than whether technical procedures are undertaken, especially for patients with high psychological morbidity.24 As Kessel observed, merely asserting that nothing is wrong can seem to deny the reality of patients' concerns.25

Achieving effective primary care management of headache is an important issue for GPs. It is estimated that GPs transferring 1% of headache referrals to neurologists will double the demand for new appointments for headache.1 The present study indicates that some GPs need to develop their skills in undertaking basic neurological examinations and may be assisted through the educational function of a GPwSI. The management of headache raises current issues of the balance between supporting individual GPs as general providers of services, and increasing the availability of primary care-based specialist provider schemes, including GPwSI, headache clinics and counselling services.26–28

Acknowledgments

We thank GPs at the following practices for participating in the research: Brigstock Medical Centre, Central Surgery (Surbiton), Cheam Family Practice, Jenner Health Centre, Manor Brook Medical Centre, Morden Hall Medical Centre, Morden Hill Group Practice, Rushey Green Group Practice, Selsdon Park Medical Practice, The Green Surgery (Twickenham), The Hurley Clinic, The Medical Centre at New Cross and The Woodcote Medical Practice. We thank Dr A Dowson and Dr L Goldstein, members of the larger project team, for commenting on drafts.

Funding body

Medical Research Council (grant number G0001083)

Ethics committee

The Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee of the South-East of England (MREC 01/01/32)

Competing interests

The authors have stated that there are none

REFERENCES

- 1.Latinovic R, Gulliford M, Ridsdale L. Headache and migraine in primary care: consultation, prescription and referral rates in a large population. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(3):385–387. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.073221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morrell DC, Wale CJ. Symptoms perceived and recorded by patients. Br J Gen Pract. 1976;26:398–403. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rasmussen BK. Epidemiology of headache. Cephalalgia. 1995;15:45–68. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1995.1501045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hasse LA, Ritchey PN, Smith R. Quantifying headache symptoms and other headache features from chart notes. Headache. 2004;44(9):873–874. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2004.04169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Goadsby PJ. Headache in clinical practice. 2nd edn. London: Martin Dunitz; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patterson VH, Esmonde TF. Comparison of the handling of neurological outpatient referrals by general physicians and a neurologist [letter] J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1993;56(7):830. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.56.7.830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ridsdale L, Clark L, Dowson A, et al. How do patients referred to neurologists for headache differ from those managed in primary care? Br J Gen Pract. 2007 in press. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Association of British Neurologists. Acute neurological emergencies in adults. London: ABN; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore AT, Roland MO. How much variation in referral rates among general practitioners is due to chance? BMJ. 1989;298(6672):500–502. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6672.500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Donnell CA. Variation in GP referral rates. Fam Pract. 2000;17(6):462–471. doi: 10.1093/fampra/17.6.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sullivan CO, Omar RZ, Ambler G, Majeed A. Case-mix and variation in specialist referral in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(516):529–533. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richie J, Spencer L, O'Connor W. Carrying out qualitative analysis. In: Ritchie J, Lewis J, editors. Qualitative research practice. London: Sage Publications; 2003. pp. 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hippisley-Cox J, Hardy C, Pringle M, et al. The effect of deprivation on variations in general practitioners' referral rates: a cross sectional study of computerised data on new medical and surgical outpatient referrals in Nottinghamshire. BMJ. 1997;314(7092):1458–1461. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7092.1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Armstrong D, Fry J, Armstrong P. Doctors' perceptions of pressure from patients for referral. BMJ. 1991;302(6786):1186–1188. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6786.1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fitzpatrick R, Hopkins A. Referrals to neurologists for headaches not due to structural disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1981;44(12):1061–1067. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.44.12.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dale N, Godsman J. Factors influencing general practitioner referrals to a tertiary pediatric neurodisability service. Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50(451):131–132. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nandy S, Chalmers-Watson C, Gantley M, Underwood M. Referral for minor mental illness: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51(467):461–465. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hyde J, Calnan M, Prior L, et al. A qualitative study exploring how GPs decide to prescribe antidepressants. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(519):755–762. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petursson P. GPs' reasons for ‘non-pharmacological’ prescribing of antibiotics: a phenomenological study. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2005;23(2):120–125. doi: 10.1080/02813430510018491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Little P, Dorward M, Warner G, et al. Importance of patient pressure and perceived pressure and perceived medical need for investigations, referral, and prescribing in primary care: nested observational study. BMJ. 2004;328(7437):444. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38013.644086.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Department of Health. Patient choice at the point of GP referral. London: The Stationery Office; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCowan C, Fahey T. Diagnosis and diagnostic testing in primary care [editorial] Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56(526):323–324. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howard L, Wessely S, Leese M, et al. Are investigations anxiolytic or anxiogenic? A randomised controlled trial of neuroimaging to provide reassurance in chronic daily headache. J Neurol Neurosurg, Psychiatry. 2005;76:1558–1564. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.057851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fitzpatrick R. Telling patients there is nothing wrong. BMJ. 1996;313(7053):311–312. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7053.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kessel N. Reassurance. Lancet. 1979;1(8126):1128–1133. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)91804-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Department of Health. Guidelines for the appointment of General Practitioners with Special Interests in the delivery of clinical services: headaches. London: The Stationary Office; 2003. pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kernick D, Mannion R. Developing an evidence base for intermediate care delivered by GPs with a special interest [editorial] Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(521):908–910. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faulkner A, Mills N, Bainton D, et al. A systematic review of the effect of primary care based service innovations on quality and patterns of referral to specialists. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53(496):878–884. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]