During the first outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Toronto, 9 health care workers at Sunnybrook and Women's College Health Sciences Centre (who were wearing the barriers and taking the precautions recommended at the time) were infected during intubation of 2 patients with probable SARS.1 In the interval between the onset of hypoxemic respiratory failure and intubation, management of these patients included use of high-flow oxygen circuits (> 15 L/min), an attempt over 1 h to institute non-invasive ventilation and a difficult intubation requiring multiple attempts by junior personnel.

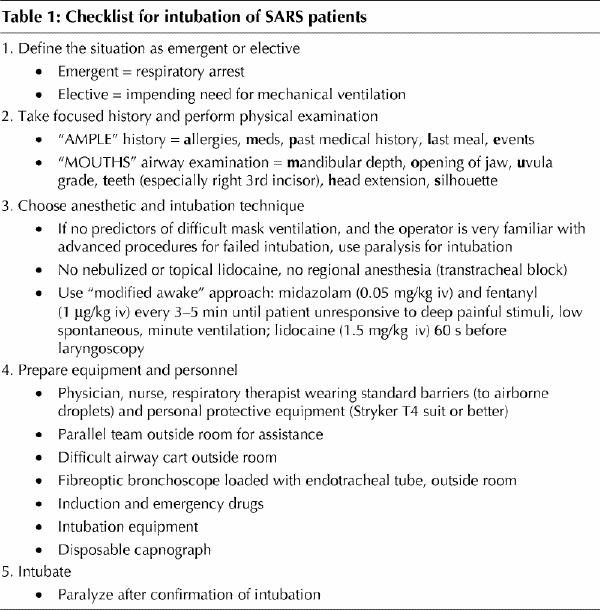

Airway management is a risky procedure in SARS patients because they shed respiratory droplets containing a high viral burden.2 Health care workers must wear appropriate equipment to protect themselves from infection. Current recommendations for protective equipment and an instructive slide presentation can be found on the Web site of Mount Sinai Hospital's Critical Care Unit.3,4 Our approach to SARS patients is summarized in the accompanying checklist (Table 1). The underlying message is: consider intubation sooner than is customary to give operators sufficient time for preparation.

Table 1

1. Define the need for intubation as emergent or elective

Classification of the patient's airway status as emergent or elective is crucial and determines the appropriate management options. We define an emergency situation as one in which a patient with probable SARS has undergone a respiratory arrest. An elective situation is one in which the patient is hypoxemic and may require mechanical ventilation. In an emergency, there may be no time to move the patient to a negative-pressure isolation room, although every effort should be made to do so. If the patient has already undergone a respiratory arrest, the use of adjunctive drugs to suppress laryngeal reflexes is unnecessary, and the protected operator simply intubates using the technique of greatest familiarity.

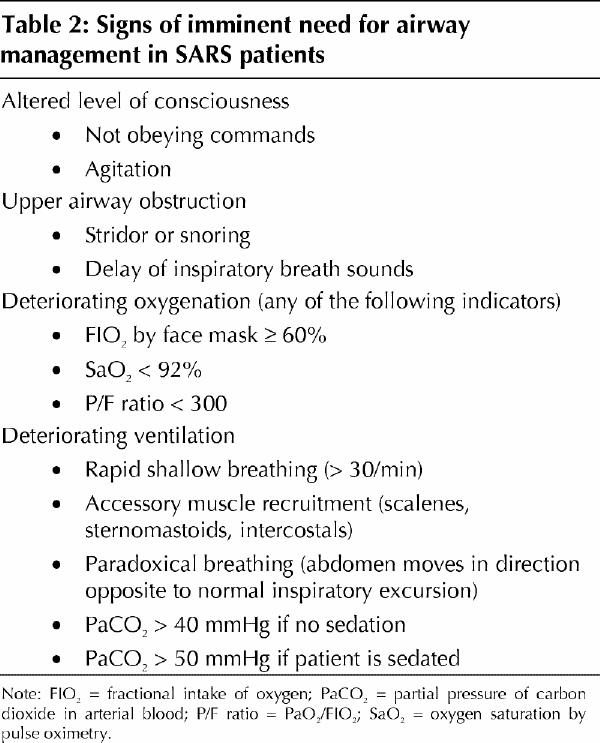

An emergency intubation represents a failure to anticipate a respiratory arrest. Management should be reviewed subsequently to improve early recognition of clinical features predicting an imminent need for airway management (Table 2).

Table 2

2. Take a focused history and perform a physical examination

As in any therapeutic approach to the airway, an examination must be undertaken before deciding on the appropriate course of action. Again, the approach depends on whether the case is emergent or elective. Use of the “AMPLE” history template (allergies, meds, past medical history, last meal, events) and a directed physical examination of the airway, such as that recommended by Davies and Eagle5 is a minimum. Additional information, such as family history (e.g., difficult intubations, malignant hyperthermia) and co-existing disease with particular attention to conditions that might result in anesthetic–drug interactions, could alter management. The degree of hepatic and renal dysfunction associated with SARS is minor, and it is unlikely that commonly used medications, with rapid clearance, would be affected by the syndrome.6

3. Choose technique for intubation

The choice of technique for intubation is always a matter of operator judgement. We believe that for the elective intubation scenario, “classic” awake intubation techniques with light intravenous sedation and topical or nebulized local anesthesia are contraindicated. This reduces the pharmacologic component of management to the choice of deep sedation, either alone or in combination with neuromuscular paralysis to abolish laryngo-spinal reflexes.

We recommend a “modified awake” intubation technique because this affords the best possible compromise between patient and operator safety. With the patient unresponsive to deep painful stimuli and maintaining low, spontaneous, minute ventilation, the response to laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation will be lowest. We use a combination of the following intravenous doses: midazolam (0.05 mg/kg), fentanyl (1 μg/kg) and lidocaine (1.5 mg/kg).7 Midazolam and fentanyl doses are repeated every 3–5 min until the patient reaches the desired level of sedation. Lidocaine is administered 60 s before laryngoscopy. Other regimens are possible provided the operator is familiar with their use.

4. Prepare equipment and personnel

The most skilled airway practitioner should intubate, as the goal is to do it rapidly, without coughing or periods of mask ventilation. The procedure is carried out in a negative-pressure room with the operator wearing personal protective equipment and isolated from the nursing unit by closed doors. Meticulous preplanning of the equipment, drugs, procedure and communication within and outside the room is required. All aspects of the procedure should be prepared for and discussed. There should be a parallel team outside the room ready to assist the physician, nurse and respiratory therapist who are inside. To counterbalance the pharmacologic effects of sedating drugs and positive-pressure ventilation resulting in a drop in blood pressure, the patient should receive a rapid bolus of crystalloid (10–20 mL/kg) to increase intravascular volume.

5. Intubate and paralyze

For a patient who is in progressive respiratory failure, the usual approach to airway management is based on the principle of maximum patient safety.8,9 For SARS patients, strict adherence to this principle must be altered because “classic” awake intubation techniques increase the risk of transmission of infection to the care team. Such techniques preserve spontaneous respiration through the use of sedation, but require airway anesthesia. Although airway anesthesia can be achieved without the use of nebulized therapy, even alternative regional anesthesia techniques such as transtracheal block can result in undesirable stimulation of the cough reflex. Accordingly, they cannot be used in patients with SARS.

We recognize that the fundamental airway management principle in anticipated difficult intubation is to avoid neuromuscular paralysis and to maintain spontaneous respiration. If the history and physical examination disclose predictors of either difficult mask ventilation or tracheal intubation, neuromuscular paralysis should not be used during intubation, except where there has been prior preparation for a surgical airway, whether temporizing (e.g., Melker cricothyrotomy) or definitive (open surgical tracheostomy). However, it would not exceed the standard of a skilled “reasonable practitioner” to give neuromuscular paralysis when there are no predictors of difficult mask ventilation or tracheal intubation. After confirmation of successful intubation with disposable capnography, the patient should be paralyzed (if this has not already been done) to prevent droplet contamination due to coughing.

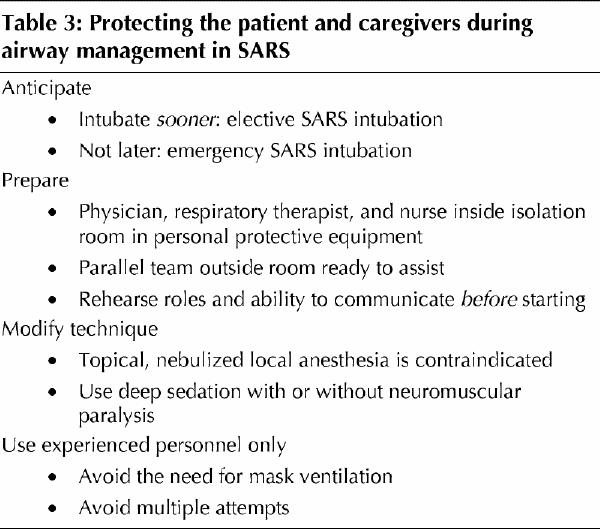

We believe that airways of patients with SARS can be managed safely for both the care team and the patient (Table 3). Intubation should be considered early in the course of hypoxemic respiratory failure, with appropriate planning as we have outlined above and in Table 2.

Table 3

Acknowledgments

We thank the Sunnybrook nurses, respiratory therapists and physicians for sharing their experiences with us during the writing of this commentary.

Footnotes

Published at www.cmaj.ca on Sept. 17, 2003.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: All authors contributed to the conception and design, analysis, drafting, critical revisions and final approval of the submitted version.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Andrew B. Cooper, Department of Critical Care Medicine, Sunnybrook and Women's College Health Sciences Centre, B708-2075 Bayview Ave., Toronto ON M4N 3M5; fax 416 480-4999

References

- 1.Population and Public Health Branch. Summary of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) cases: Canada and international. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2003. Available: www.hc-sc.gc.ca/pphb-dgspsp/sars-sras/eu-ae/sars20030502_e.html (accessed 2003 Aug 19).

- 2.Ofner M, Lem M, Sarwal S, Vearncombe M, Simor A. Cluster of severe acute respiratory syndrome cases among protected health care workers — Toronto, April 2003. Can Commun Dis Rep 2003;29(11):93-7. Available: www.hc-sc.gc.ca/pphb-dgspsp/publicat/ccdr-rmtc/03vol29/dr2911ea.html (accessed 2003 Aug 19). [PubMed]

- 3.Wax R, Brunet F, Peerbaye Y, Castle M, Abrahamson S, Darrah W, et al., for the Working Group on Adjunctive Protective Equipment for High-Risk Procedures in SARS Patients. Draft report — circulated for comment, April 28, 2003. Toronto: Technology Application Unit, Mount Sinai Hospital; 2003. Available: sars.medtau.org/adjunctreport.doc (accessed 2003 Aug 19).

- 4.Wax R, Mazurik L, Campbell VT. Using the Stryker T4 personal protection system for high-risk procedures during SARSoutbreaks. Toronto: The Greater Toronto Area Critical Care/Emergency Medicine Advisory Group, Mount Sinai Hospital; 2003. Available: sars.medtau.org/strykertraining.htm (accessed 2003 Aug 19).

- 5.Davies JM, Eagle CJ. M.O.U.T.H.S. Can J Anesth 1991;38(5):687-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preliminary clinical description of severe acute respiratory syndrome. JAMA 2003;289(15):1920-1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Stoelting RK, editor. Pharmacology and physiology in anesthetic practice. Philadelphia: Lippincot Williams & Wilkins; 1998.

- 8.Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway. A report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology 1993;78(3):597-602. [PubMed]

- 9.George E, Haspel KL. The difficult airway. Int Anesthesiol Clin 2000;38(3):47-63. [DOI] [PubMed]