Abstract

The estrogen receptor (ER) is a member of a large superfamily of nuclear receptors that regulates the transcription of estrogen-responsive genes. Several recent studies have demonstrated that XBP-1 mRNA expression is associated with ERα status in breast tumors. However, the role of XBP-1 in ERα signaling remains to be elucidated. More recently, two forms of XBP-1 were identified due to its unconventional splicing. We refer to the spliced and unspliced forms of XBP-1 as XBP-1S and XBP-1U, respectively. Here, we report that XBP-1S and XBP-1U enhanced ERα-dependent transcriptional activity in a ligand-independent manner. XBP-1S had stronger activity than XBP-1U. The maximal effects of XBP-1S and XBP-1U on ERα transactivation were observed when they were co-expressed with full-length ERα. SRC-1, the p160 steroid receptor coactivator family member, synergized with XBP-1S or XBP-1U to potentiate ERα activity. XBP-1S and XBP-1U bound to the ERα both in vitro and in vivo in a ligand-independent fashion. XBP-1S and XBP-1U interacted with the ERα region containing the DNA-binding domain. The ERα-interacting regions on XBP-1S and XBP-1U have been mapped to two regions, including the N-terminal basic region leucine zipper domain (bZIP) and the C-terminal activation domain. The bZIP-deleted mutants of XBP-1S and XBP-1U completely abolished ERα transactivation by XBP-1S and XBP-1U. These findings suggest that XBP-1S and XBP-1U may directly modulate ERα signaling in both the absence and presence of estrogen and, therefore, may play important roles in the proliferation of normal and malignant estrogen-regulated tissues.

INTRODUCTION

The estrogen receptor (ER) belongs to a superfamily of nuclear receptors that act as ligand-activated transcription factors [for reviews see Klinge (1), Katzenellenbogen and Katzenellenbogen (2), and Aranda and Pascual (3)]. Based on structural and functional similarities (4,5), the nuclear receptors can be subdivided into six regions (A–F). Two domains are well conserved among nuclear receptors, the highly conserved C domain serving to direct DNA binding and the moderately conserved C-terminal E/F domain forming a pocket for ligand binding. The ligand-binding domain (LBD) contains a ligand-dependent transcriptional activation function (AF-2), whereas the quite divergent A/B domain contains another transactivation function (AF-1), which is constitutive in the absence of ligand. There are two isoforms of ERs, namely ERα and ERβ [Kuiper et al. (6,7), and references therein]. Activation of ERα is responsible for many biological processes, including cell growth and differentiation, morphogenesis and programmed cell death (8,9). In addition, ERα plays an important role in the development and progression of breast cancer by regulating genes and signaling pathways involved in cellular proliferation. Regulation of gene expression by the ERα requires the coordinate activity of ligand binding, phosphorylation and cofactor interactions, with particular combinations probably resulting in the tissue-specific responses elicited by the receptor (10–13). However, the intracellular signaling pathways modulating these components and regulating ERα transcriptional activity are not fully understood.

Human X box-binding protein 1 (XBP-1), originally identified as a protein binding to the cis-acting X box present in the promoter regions of target genes, is a basic region leucine zipper (bZIP) protein in the CREB/ATF (cAMP response element-binding protein/activating transcription factor) family of transcription factors (14). XBP-1 has been found to be ubiquitously expressed in adult tissues but preferentially expressed in fetal exocrine glands, osteoblasts, chondroblasts and liver (14,15). XBP-1 is essential for the growth of hepatocytes (16), as XBP-1-deficient embryos die in utero from severe liver hypoplasia and the resultant fatal anemia. In human multiple myeloma cells, XBP-1 has been shown to be implicated in the proliferation of malignant plasma cells (17). Since the cloning of XBP-1 over 10 years ago (14), there has been general acceptance that only one XBP-1 existed. More recently, however, XBP-1 mRNA has been shown to be unconventionally spliced by IRE1 in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress (18,19), resulting in production of a highly active transcription factor that can activate the mammalian unfolded protein response (UPR). The unconventional splicing of XBP-1 mRNA results in a frameshift at amino acid 165 of the unspliced XBP-1. Thus, unspliced and spliced XBP-1 mRNA encode proteins of 261 and 376 amino acids, respectively, with the identical N-terminal regions containing the bZIP domain. We refer to the spliced and unspliced forms of XBP-1 as XBP-1S and XBP-1U, respectively.

XBP-1 has been reported to be expressed at high levels in ERα-positive breast tumors (20–25), although the forms of XBP-1 are unknown. Using cDNA arrays, Perou et al. described that variation of the ERα gene in 65 surgical specimens of human breast tumors from 42 different individuals paralleled variation in the expression of the XBP-1 gene (20). Bertucci et al. compared the gene expression profiles in ERα-positive breast cancers (n = 23) versus ERα-negative breast cancers (n = 11) with cDNA array technology (22). The XBP-1 mRNA expression in ERα-positive breast cancers was 2.7-fold as much as that in ERα-negative breast cancers. SAGE (serial analysis of gene expression) showed that XBP-1 appeared to be highly expressed in cancerous mammary epithelial cells (26). Because of the importance of ERα signaling in the regulation of breast cancer development and progression, we investigated the potential role of XBP-1 in ERα transcriptional activity. Here, we show that both XBP-1S and XBP-1U enhance ERα transactivation in breast cancer and non-breast cells in a ligand-independent manner. We further present in vitro and in vivo evidence that XBP-1S and XBP-1U interact with ERα, and that deletion of the N-terminal portion of XBP-1S and XBP-1U fully abolishes the ERα transcriptional activity by XBP-1S and XBP-1U.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids

The following plasmids have been described previously: pERE-LUC (estrogen-responsive element-containing luciferase reporter) (27), a kind gift from Dr Ming-jer Tsai (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX); pcDNA3-ERα (human ERα expression vector) (27); pCMX-SRC-1 (28), a kind gift from Dr Rosalie M. Uht (University of Virginia, VA); pcDNA-hAR [human androgen receptor (AR) expression vector] (29); and PSA-LUC [androgen responsive element (ARE)-containing luciferase reporter] (29), a generous gift from Dr Chinghai Kao (University of Indiana, Indianapolis, IN). To construct pcDNA3-FLAG-XBP-1S, full-length human XBP-1S cDNA was obtained by standard PCR amplification from an ovary two-hybrid cDNA library (Clontech). Full-length human XBP-1U cDNA was obtained using recombinant PCR (27). The amplified XBP-1S and XBP-1U cDNAs were both cloned into pcDNA3 vector harboring FLAG epitope sequence (pcDNA3-FLAG), and the constructs were confirmed by sequencing. Deletion mutants of XBP-1S and XBP-1U were constructed by inserting PCR-generated fragments from the corresponding XBP-1 cDNAs into the pcDNA3-FLAG vector. The expression vectors for ERα AF-1 (amino acids 1–282) and ERα AF-2 (amino acids 178–595) were constructed by introducing the cDNAs into pcDNA3 (Invitrogen). Constructs encoding GST fusion proteins were prepared by amplification of each sequence by standard PCR methods, and the resulting fragments were cloned in-frame into pGEX-KG (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), using appropriate restriction sites as described previously (30). The constructs were partially sequenced to confirm the correct orientation.

Mammalian cell transfection and luciferase assay

MDA-MB-435, MCF-7 and 293T cells were routinely cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen) containing 10% newborn calf serum at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. For transfection, MDA-MB-435, MCF-7 and 293T cells were seeded in 12-well plates containing phenol red-free RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% charcoal dextran-treated fetal bovine serum (Hyclone). The cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) with 0.2 µg of ERE-LUC or PSA-LUC reporter plasmid, 50 ng of ERα or AR expression vector, 0.1 µg of β-galactosidase reporter, and 20 ng–0.5 µg of the expression vectors for XBP-1S or XBP-1U, and the respective empty vector was used to adjust the total amount of DNA. After treatment with 10 nM 17β-estradiol (E2; for ERα) or 2 nM R1881 (for AR) for 24 h, the transfected cells were harvested, and luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were determined as described previously (27). β-Galactosidase activity was used as an internal control for transfection efficiency. All experiments were repeated at least three times with similar results.

GST pull-down assay

GST and GST fusion proteins were expressed and purified according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Pharmacia), with the induction of protein expression performed at 20°C overnight (30). The expression vector for ERα, XBP-1S or XBP-1U was used for in vitro transcription and translation in the TNT Reticulocyte Lysate System (Promega). The 35S-labeled ERα, XBP-1S or XBP-1U was mixed with 10 µg of GST derivatives bound to glutathione–Sepharose beads in 0.5 ml of binding buffer [50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.3 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.1% NP-40 and protease inhibitor tablets from Roche]. The binding reaction was performed at 4°C overnight and the beads were subsequently washed four times with the washing buffer (the same as the binding buffer), 30 min each time. The beads were eluted in 10 µl of 2× SDS–PAGE sample buffer and the proteins were resolved on a 10% denaturing gel. The gel was then dried and exposed to X-ray films overnight.

Co-immunoprecipitation

293T cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). At 24 h post-transfection, cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in 0.5 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris at pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM DTT and protease inhibitor tablets from Roche). After brief sonication, the lysate was centrifuged at 14 000 r.p.m. for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was used for subsequent co-immunoprecipitation (30). A 15 µl aliquot of 50% slurry of the anti-FLAG agarose beads (Sigma-Aldrich) was used in each immunoprecipitation. Immunoprecipitation was performed overnight at 4°C. The beads were centrifuged at 3000 r.p.m. for 2 min, and washed four times with the washing buffer (the same as the lysis buffer), with each wash lasting at least 30 min. The precipitates were then eluted in 30 µl of 2× SDS–PAGE sample buffer and loaded on SDS–polyacrylamide gels, followed by western blotting according to the standard procedures. A 4 µl aliquot of the input crude extract was used for detecting protein expression levels. The ERα proteins were detected using an anti-ERα polyclonal antibody (HC-20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Gel shift assay

The double-stranded oligonucleotide (31), corresponding to the consensus ERE (5′-AGCTCTTTGATCAGGTCACTGTGACCTGACTTT-3′) or mutant ERE (EREM; 5′-AGCTCTTTGATCAGTACACTGTGACCTGACTTT-3′), was 32P-labeled using T4 polynucleotide kinase (Promega). Binding reactions (20 µl) were performed in the presence or absence of ligands (1 µM) for 30 min using in vitro translated protein or the same amount of unprogrammed lysate (Promega) in 10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 4% glycerol, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT and 0.1 µg/µl poly(dT–dC). The labeled ERE (0.5 ng) or EREM (0.5 ng) was then added, incubated for 20 min at room temperature, and analyzed on a 5% polyacrylamide gel. Protein–DNA binding was visualized by autoradiography.

RT–PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen). First strand cDNA was reverse transcribed from 1.0 µg of total RNA with oligo(dT) primers using AMV reverse transcriptase as recommended by the supplier (Promega). A 1 µl aliquot of the first strand cDNA synthesis reaction mixture was used for PCR amplification in a total volume of 50 µl. The oligonucleotides 5′-TCTGCTGAGTCCGCAGCAG-3′ and 5′-GAAAAGGGAGGCTGGTAAGGAAC-3′ were used for amplification of a 233 bp fragment of XBP-1S, and 5′-TGGTTGCTGAAGAGGAGGCGGAAG-3′ and 5′-GAGATGTTCTGGAGGGGTGACAACTG-3′ for amplification of a 136 bp fragment of XBP-1U. PCR amplifications were performed for 35 cycles using the following cycling parameters: 94°C for 1 min, 68°C for 1 min and 72°C for 1 min. The RT–PCR products were purified and ligated to a T vector, and the resulting positive clones were sequenced. β-Actin was amplified as described previously (32), and used as an internal control.

RESULTS

Potentiation of ERα transcriptional activity by XBP-1S and XBP-1U

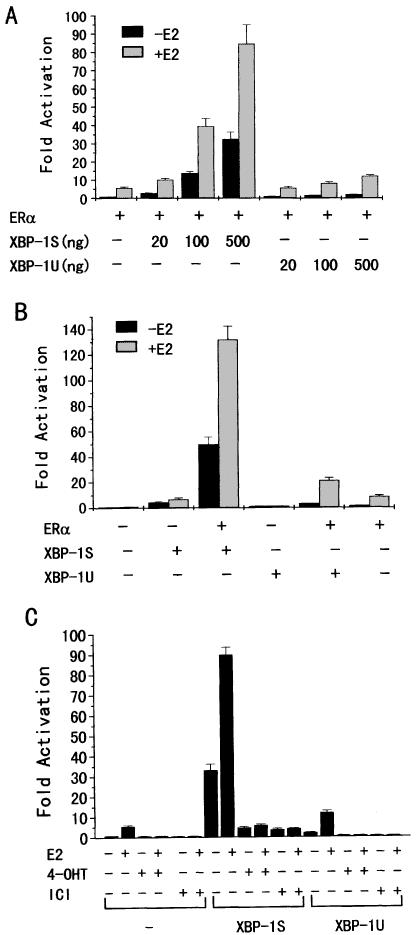

To investigate the effects of the XBP-1 proteins on ERα transcriptional activity, human breast cancer MDA-MB-435 cells, which lack the ERα, were co-transfected with the estrogen response element-containing reporter ERE-LUC, ERα and increasing amounts of XBP-1S or XBP-1U. As shown in Figure 1A, in the absence and presence of E2, 0.5 µg of XBP-1S enhanced the transcriptional activity of ERα 32- and 15-fold, respectively, whereas 0.5 µg of XBP-1U only enhanced ERα transcriptional activity 2.1- and 2.2-fold, respectively. This might be explained by the structural differences between the C-terminal transactivation domains of XBP-1S and XBP-1U. Both XBP-1S and XBP-1U increased ERα transcriptional activation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1A). It is important to note that the magnitude of the ligand-independent activation of the ERα by XBP-1S (0.5 µg) was 5-fold higher than that observed with E2 (10 nM), and that XBP-1S and estrogen were synergistic in stimulating estrogen-regulated transcription. The activity of the ERE-LUC reporter activated by XBP-1S and XBP-1U decreased dramatically in the absence of exogeneous ERα (Fig. 1B), indicating that ERα itself was required for the maximal effects of XBP-1S and XBP-1U on ERE-LUC reporter transcription.

Figure 1.

XBP-1S and XBP-1U enhance ERα-mediated transactivation in MDA-MB-435 cells. (A) Effects of XBP-1S and XBP-1U on ERα-mediated transactivation. Cells were co-transfected with 0.2 µg of ERE-LUC, 50 ng of the expression plasmid for ERα and increasing amounts of the expression vector for either XBP-1S or XBP-1U as indicated. Cells were then treated with control (0.1% ethanol) vehicle or 10 nM E2 for 24 h before luciferase assay. The LUC activity obtained on transfection of ERE-LUC and ERα without exogenous XBP-1S and XBP-1U in the absence of E2 was set as 1. Results are expressed as means ± SE for three independent experiments. (B) Effect of ERα on ERE-LUC reporter gene transcription by XBP-1S and XBP-1U. Cells were co-transfected with 0.2 µg of ERE-LUC and 0.5 µg of the expression vector for either XBP-1S or XBP-1U in both the absence and presence of the expression plasmid for ERα. Cells were then treated and analyzed as in (A). (C) Effects of antiestrogens on ERE-LUC reporter gene transcription by XBP-1S and XBP-1U. Cells were co-transfected with 0.2 µg of ERE-LUC, 50 ng of the expression plasmid for ERα and 0.5 µg of the expression vector for either XBP-1S or XBP-1U. Cells were then treated with control (0.1% ethanol) vehicle, 10 nM E2, 100 nM 4-OHT or 100 nM ICI 182,780 for 24 h before luciferase assay. Cells were analyzed as in (A).

To examine the effects of antiestrogens on ERα transactivation by XBP-1S and XBP-1U, MDA-MB-435 cells were co-transfected with the ERE-LUC reporter, ERα and XBP-1S or XBP-1U, and subsequently treated with antiestrogens, 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) and ICI 182,780 (Fig. 1C). Both ICI 182,780 and 4-OHT completely blocked the effects of XBP-1U on ERα transcriptional activity in the presence or absence of E2, whereas both ICI 182,780 and, to a lesser extent, 4-OHT reduced but did not abolish the ability of XBP-1S to transactivate ERα.

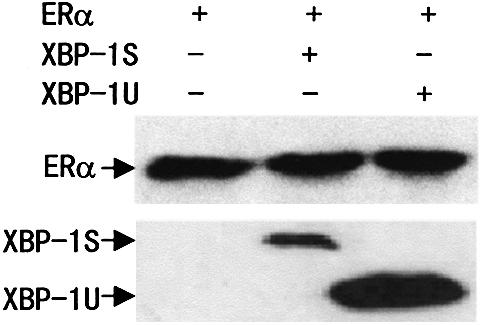

To determine whether the observed effects of XBP-1S and XBP-1U on ERα transactivation were specific to MDA-MB-435 cells, human breast cancer cell line MCF-7 and human embryonic kidney cell line 293T were used in co-transfection experiments. Although ERα transactivation by XBP-1S in MCF-7 and 293T cells was of a lower magnitude than in MDA-MB-435 cells, similar results were observed (Table 1). The transcriptional activity of ERα co-activated by XBP-1S was always greater than that co-activated by XBP-1U. Thus, XBP-1S and XBP-1U can act as positive regulators of ERα-dependent transcriptional activation in a variety of mammalian cell lines. To verify that this E2-independent enhanced transcriptional activity was not a result of increased ERα protein production, we examined protein expression in whole-cell extracts using western blotting analysis. Figure 2 shows that ERα levels were not increased by XBP-1S or XBP-1U expression. In addition, the greater effects of XBP-1S on ERα transcriptional activation were also not attributable to its high expression level. Conversely, the expression level of XBP-1S was lower than that of XBP-1U (Fig. 2). Together, our results suggest that XBP-1S and XBP-1U could function as a co-regulator to enhance ERα transcriptional activity in a ligand-independent manner.

Table 1. XBP-1S and XBP-1U enhance ERα-mediated transactivation.

| Expressed proteins | Activation of transcription (fold activation) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCF7 cells | 293T cells | |||

| –E2 | +E2 | –E2 | +E2 | |

| ERα | 1 | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 1 | 5.3 ± 0.6 |

| ERα, XBP-1S | 5.1 ± 0.6 | 14.0 ± 1.2 | 7.6 ± 0.8 | 28.8 ± 3.0 |

| ERα, XBP-1U | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 7.3 ± 0.5 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 10.3 ± 0.6 |

Cells were transfected, treated and analyzed as described in the legend to Figure 1A.

Figure 2.

Western blotting showing the ERα, XBP-1S and XBP-1U protein levels in 293T cells. Cells were transfected as in Table 1. Whole-cell extracts were prepared, and equivalent amounts of each extract were probed with anti-ERα antibody (H-184; Santa Cruz Biotech) or anti-XBP-1 antibody (SC-7160; Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

To determine the specificity of XBP-1S and XBP-1U in ERα-mediated transactivation, we tested the effects of XBP-1S and XBP-1U on AR-mediated transactivation using the ARE-containing reporter construct PSA-LUC. As expected, transcription of the reporter was induced by an androgen, R1881, in MDA-MB-435, MCF-7 and 293T cells (Table 2). XBP-1S and XBP-1U failed, however, to enhance AR-mediated transcription in both the presence and absence of R1881. Conversely, in the presence and absence of R1881, XBP-1S decreased AR transcriptional activity ∼2- and 4-fold, respectively, in MCF-7 and 293T cells (Table 2). This result suggests that XBP-1S and XBP-1U may not be general co-activators for steroid receptors.

Table 2. XBP-1S and XBP-1U do not enhance AR-mediated transactivation.

| Expressed proteins | Activation of transcription (fold activation) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDA-MB-435 cells | MCF7 cells | 293T cells | ||||

| –R1881 | +R1881 | –R1881 | +R1881 | –R1881 | +R1881 | |

| AR | 1 | 10.2 ± 1.2 | 1 | 12.5 ± 1.0 | 1 | 20.5 ± 0.8 |

| AR, XBP-1S | 0.62 ± 0.1 | 14.1 ± 3.3 | 0.25 ± 0.04 | 6.6 ± 1.9 | 0.27 ± 0.05 | 9.6 ± 0.3 |

| AR, XBP-1U | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 14.2 ± 1.0 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 10.7 ± 2.8 | 0.94 ± 0.17 | 20.5 ± 3.4 |

Cells were co-transfected with 0.2 µg of PSA-LUC, 50 ng of the expression plasmid for AR and 0.5 µg of the expression vector for either XBP-1S or XBP-1U, as indicated. Cells were then treated with control (0.1% ethanol) vehicle or 2 nM R1881 for 24 h before luciferase assay. The LUC activity obtained on transfection of PSA-LUC and AR without exogenous XBP-1S and XBP-1U in the absence of R1881 was set as 1.

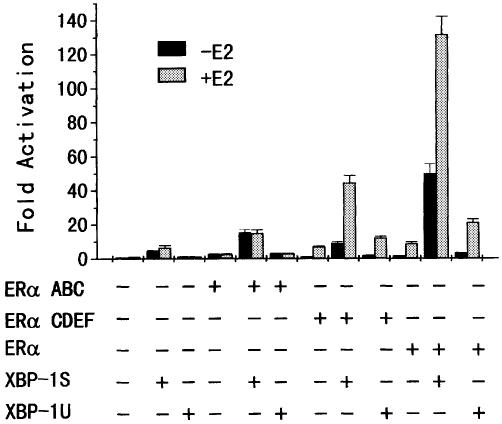

Both the N- and C-terminal domains of ERα contribute to ERα transactivation by XBP-1S and XBP-1U

To determine which domain of ERα is involved in the co-activation of ERα by XBP-1S and XBP-1U, ERα constructs containing N-terminal AF-1 and DNA-binding domain (DBD) (ABC domain) or C-terminal AF-2 and DBD (CDEF domain) were co-expressed with XBP-1S or XBP-1U in MDA-MB-435 cells. XBP-1S and, to a lesser extent, XBP-1U enhanced both the constitutive transactivation activity of AF-1 and ligand-dependent transcriptional activity of AF-2 (Fig. 3). However, co-expression of XBP-1S or XBP-1U with full-length ERα resulted in a more efficient enhancement of the reporter transcriptional activity (2- to 5-fold), compared with ABC and CDEF domains expressed separately (Fig. 3). Thus, both N- and C-terminal domains of ERα contribute to ERα transcriptional activity by XBP-1S and XBP-1U.

Figure 3.

Both N- and C-terminal domains contribute to ERα transcriptional activity regulated by XBP-1S and XBP-1U. MDA-MB-435 cells were co-transfected with 50 ng of the expression vector for ERα, ERα ABC domain or ERα CDEF domain, 0.2 µg of ERE-LUC and 0.5 µg of the expression vector for either XBP-1S or XBP-1U as indicated. The LUC activity obtained on transfection of ERE-LUC without exogenous ERα, ERα ABC domain, ERα CDEF domain, XBP-1S and XBP-1U in the absence of E2 was set as 1. Results are expressed as means ± SE for three independent experiments.

Cooperative co-activation of ERα by XBP-1 and SRC-1

SRC-1 is a member of the p160 steroid receptor coactivator (SRC) family (33). SRC-1 interacts with ERα and stimulates E2-mediated gene transcription. SRC-1 enhances the interaction between the N-terminal AF-1-containing and C-terminal AF-2-containing regions of the ERα, allowing for full ERα activation. To determine whether XBP-1 plays a role in SRC-1-mediated co-activation of the ERα, MDA-MB-435 cells were co-transfected with the ERE-LUC reporter construct and expression vectors for XBP-1 and SRC-1 (Table 3). As expected, in the absence of E2, transfection of XBP-1S or XBP-1U alone co-activated ERα transcriptional activity, whereas transfection of SRC-1 did not have a significant effect. Co-transfection with XBP-1S or XBP-1U, plus SRC-1 expression vectors gave greater than additive effects of XBP-1S or XBP-1U and SRC-1 measured independently. In the presence of E2, XBP-1S, XBP-1U and SRC-1 all enhanced ERα transcriptional activity to different levels. When SRC-1 was co-expressed with either XBP-1S or XBP-1U, however, the ERα transcriptional activity was cooperatively enhanced. Therefore, the synergistic enhancement of ERα activity by co-expression of SRC-1 and XBP-1S or XBP-1U is ligand independent.

Table 3. Synergistic enhancement of ERα activity by SRC-1 and XBP-1.

| Expressed proteins | Activation of transcription (fold activation) | |

|---|---|---|

| –E2 | +E2 | |

| ERα | 1 | 4.0 ± 0.3 |

| ERα, XBP-1S | 22.5 ± 1.5 | 68.4 ± 5.8 |

| ERα, XBP-1U | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 9.2 ± 0.9 |

| ERα, SRC-1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 11.4 ± 1.0 |

| ERα, SRC-1, XBP-1S | 53.2 ± 2.9 | 136.3 ± 7.7 |

| ERα, SRC-1, XBP-1U | 5.3 ± 0.4 | 37.1 ± 2.0 |

MDA-MB-435 cells were co-transfected with 0.2 μg of ERE-LUC, 50 ng of the expression vector for ERα, 0.5 μg of the expression vector for SRC-1 and 0.5 μg of the expression vector for either XBP-1S or XBP-1U, as indicated. Cells were treated and analyzed as described in the legend to Figure 1A.

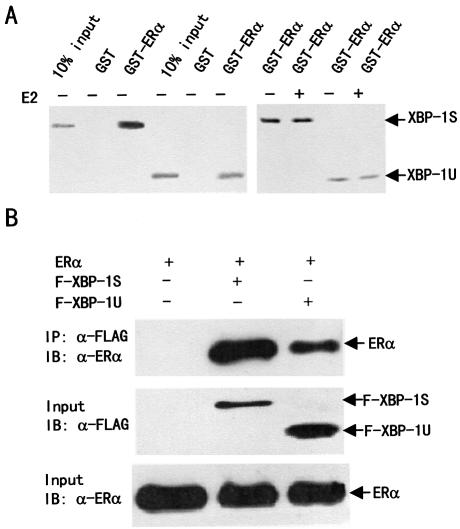

Interaction of XBP-1S and XBP-1U with ERα in vitro and in vivo

Our observation that XBP-1S and XBP-1U could function as a co-regulator to enhance ligand-independent ERα transactivation suggested that XBP-1S and XBP-1U might physically interact with ERα. To test this possibility, GST pull-down experiments were performed in which in vitro translated [35S]methionine-labeled XBP-1S or XBP-1U was incubated with full-length GST–ERα. The binding of XBP-1S and XBP-1U to GST–ERα, but not to GST, was observed in both the absence and presence of E2 (Fig. 4A). E2 did not increase the interaction of XBP-1S and XBP-1U with GST–ERα. Notably, the binding of XBP-1S to ERα was stronger than that of XBP-1U to ERα.

Figure 4.

XBP-1S and XBP-1U bind to ERα in vitro and in vivo. (A) Interaction of XBP-1S and XBP-1U with ERα in vitro. GST pull-down assay was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Full-length GST–ERα fusion proteins, immobilized on beads, were mixed with in vitro translation reaction mixtures of XBP-1S or XBP-1U in the absence or presence of E2 (10–6 M) as indicated. The bound proteins were subjected to SDS–PAGE followed by autoradiography. (B) Interactions between either XBP-1S or XBP-1U and ERα in vivo. 293T cells were co-transfected with the expression vectors for either the FLAG-tagged XBP-1 or the FLAG-tagged XBP-1U and ERα as indicated. Lysates from the transfected cells were immunoprecipitated (IP) using anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma-Aldrich), and the immunoprecipitates were probed with an anti-ERα antibody (HC-20; Santa Cruz Biotech). (C) Mapping of interaction regions of XBP-1S and XBP-1U in ERα. GST pull-down assay was performed using 35S-labeled XBP-1S or XBP-1U and fusion proteins between GST and three different ERα fragments. (D) Mapping of the ERα interaction region in XBP-1S and XBP-1U. GST pull-down assay was performed using 35S-labeled ERα and fusion proteins between GST and six different XBP-1 fragments.

To determine whether XBP-1S and XBP-1U interact with ERα in vivo, 293T cells were transfected with ERα and FLAG-tagged XBP-1S or XBP-1U and cultured in both the absence (Fig. 4B) and presence of 10 nM E2 (data not shown). FLAG-XBP-1S or XBP-1U was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates by an anti-FLAG antibody and analyzed for ERα binding by western blotting analysis. The results showed that ERα could be co-immunoprecipitated in a ligand-independent manner in the presence, but not in the absence, of FLAG-XBP-1S or FLAG-XBP-1U (Fig. 4B, and data not shown). Consistent with the co-activation results, the binding of XBP-1S to ERα was stronger than that of XBP-1U to ERα. The in vivo interaction of XBP-1S and XBP-1U with ERα was unlikely to be mediated by nucleic acids, as it was not affected by the treatment with ethidium bromide that disrupts DNA–protein interaction (data not shown).

Mapping of the ERα and XBP-1 interaction domains

To determine which region of ERα binds to XBP-1S or XBP-1U, GST pull-down experiments were performed. As shown in Figure 4C, the GST–ERα(180–282) containing the DBD bound specifically to in vitro translated [35S]methionine-labeled XBP-1S or XBP-1U, but the GST-ERα(1–185) containing the AF-1 and the GST–ERα(282–595) containing the AF-2 did not. Consistent with the in vivo binding results, XBP-1S interacted with GST–ERα(180–282) in vitro more strongly than XBP-1U.

XBP-1S and XBP-1U are proteins of 261 and 376 amino acids, respectively, with an identical N-terminus (amino acids 1–164). To delineate the domains in the XBP-1S and XBP-1U that mediate the protein–protein interaction with ERα, a series of mutant GST–XBP-1 fusion proteins were used in GST pull-down experiments (Fig. 4D). Deletion of the XBP-1 N-terminal amino acids (1–82) reduced but did not abolish the ability of the XBP-1 proteins to bind to the ERα. Either region (amino acids 1–101, containing the bZIP domain, or either amino acids 148–376 or amino acids 148–261, containing the transactivation domain) of XBP-1S or XBP-1U was sufficient for ERα binding. However, the full-length GST–XBP-1 interacted with ERα more strongly than any GST–XBP-1 fragments. In addition, GST–XBP-1S associated with ERα more strongly than GST–XBP-1U.

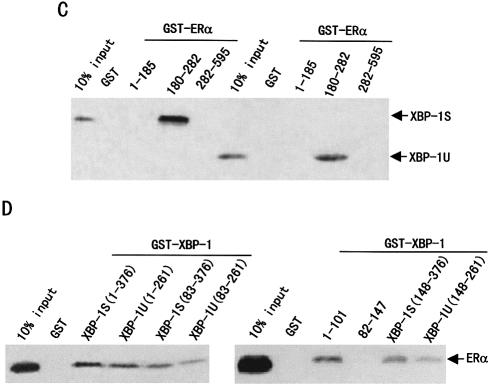

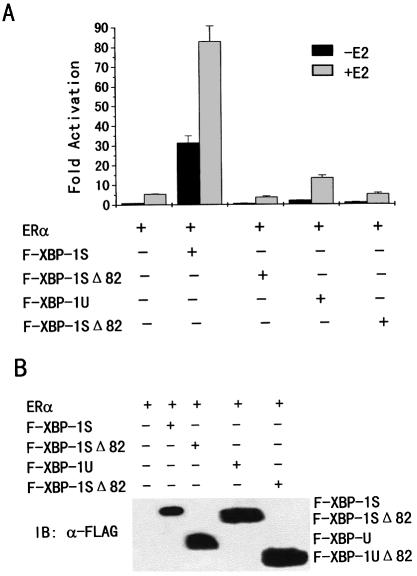

The N-terminal portion of XBP-1 is required for ERα transactivation function

To test the possibility that the maximal interaction of XBP-1S and XBP-1U with ERα is required for the enhancement of ERα transcriptional activation, mutants of XBP-1S and XBP-1U (ΔXBP-1S and ΔXBP-1U) were made in which the N-terminal region from amino acids 1 to 82 was deleted. MDA-MB-435 cells were co-transfected with the ERE-LUC reporter, ERα and either FLAG-tagged XBP-1S, XBP-1U, ΔXBP-1S or ΔXBP-1U. As shown in Figure 5A, the mutations lacking some of the ERα-binding sites completely abolished the ERα transcriptional activation in a ligand-independent manner. This is not attributable to decreased expression of the ΔXBP-1S and the ΔXBP-1U deletion mutants. In contrast, ΔXBP-1S and ΔXBP-1U were expressed at higher levels than XBP-1S and XBP-1U (Fig. 5B). Taken together, these findings suggest that the XBP-1S and XBP-1U action of ERα by their maximal binding contributes to the transactivation function of ERα.

Figure 5.

The deletion mutants of XBP-1S and XBP-1U abolished the ERα transactivation. (A) MDA-MB-435 cells were co-transfected with 0.2 µg of ERE-LUC, 50 ng of the expression plasmid for ERα and 0.5 µg of the expression vector for FLAG-tagged XBP-1S, XBP-1SΔ82, XBP-1U or XBP-1UΔ82 as indicated. Cells were then treated with control (0.1% ethanol) vehicle or 10 nM E2 for 24 h before luciferase assay. The LUC activity obtained on transfection of ERE-LUC and ERα without exogenous XBP-1 and its derivatives in the absence of E2 was set as 1. Results are expressed as means ± SE for three independent experiments. (B) Western blotting showing expression of FLAG-tagged XBP-1S, XBP-1SΔ82, XBP-1U and XBP-1UΔ82. Cells were transfected as in (A). Whole-cell extracts were prepared, and equivalent amounts of each extract were probed with anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma-Aldrich).

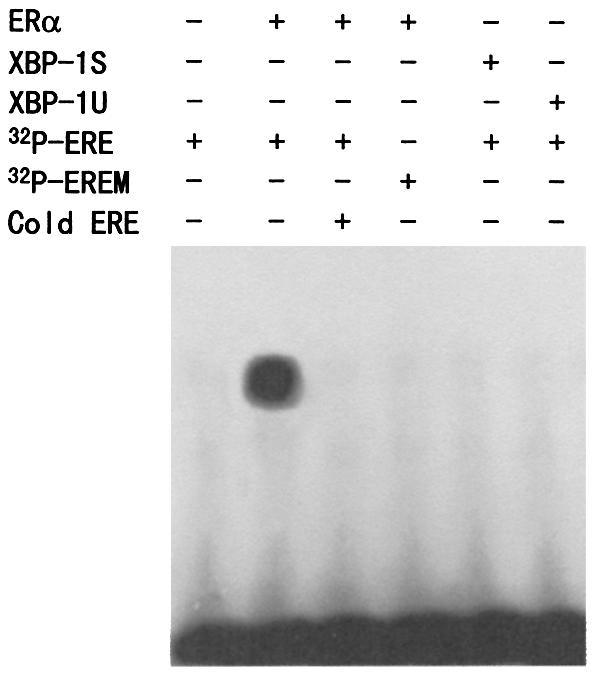

Neither XBP-1S nor XBP-1U binds to ERE

The transcription factor XBP-1 was found to bind preferably to the cAMP responsive element (CRE)-like element GATGACGTG(T/G)nnn(A/T)T (34). ERα binds to the ERE GGTCAnnnTGACC. Since both XBP-1 and ERα target sequences have the sequence TGAC, we tested whether XBP-1S and XBP-1U bind to the consensus ERE, using a gel shift assay. As expected, the 32P-labeled ERE, but not mutant ERE (EREM), bound to in vitro-translated ERα in the absence or presence of E2 (Fig. 6 and data not shown). The binding was specifically inhibited by a 100-fold molar excess of a cold ERE oligonucleotide. Moreover, neither XBP-1S nor XBP-1U bound to the ERE.

Figure 6.

Neither XBP-1S nor XBP-1U binds to ERE. Gel shift assay was performed as described in Materials and Methods. The 32P-labeled ERE probe was incubated with the in vitro-translated ERα, XBP-1S and XBP-1U proteins as indicated, in the presence of 1 µM E2. For competition experiments, a 100-fold molar excess of unlabeled ERE was mixed with the radioactive probe. The 32P-labeled mutant ERE (EREM) probe was used as a negative control.

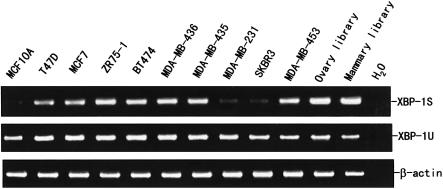

XBP-1S and XBP-1U mRNAs are expressed in breast cancer cell lines

Human XBP-1 (XBP-1U) was originally isolated as a transcription factor which binds to the X2 box present in the promoter region of human major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II genes (14). More recently, XBP-1U mRNA was found to be spliced in response to the endoplasmic reticulum stress, resulting in XBP-1S (18,19). To determine whether XBP-1S mRNA is expressed in breast cancer cells, we prepared mRNA from five ER-positive (MCF10A, T47D, MCF7, ZR75-1 and BT474) and five ER-negative (MDA-MB-436, MDA-MB-435, MDA-MB-231, SKBR3 and MDA-MB-453) breast cancer cell lines and performed RT–PCR using primers specific for the unique XBP-1S region. As shown in Figure 7, in addition to XBP-1U mRNA, we could also detect XBP-1S mRNA in all of the breast cancer cell lines tested. The identity of XBP-1S detected was further confirmed by DNA sequencing. XBP-1S was also expressed in the immortalized normal breast epithelial cell line MCF-10A, although at a lower level. Since a limited number of breast cancer cell lines were examined, there is no significant correlation between XBP-1 and ERα expression. However, both XBP-1S and XBP-1U were widely expressed in breast cancer cells. Interestingly, XBP-1S was also expressed in mammary and ovary two-hybrid cDNA libraries, which were prepared from the corresponding tissues of individuals who died from trauma, indicating that XBP-1S is more widely expressed than previously thought. After searching expressed sequence tags (ESTs) for XBP-1S in GenBank (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast), we also found that human XBP-1S mRNA is expressed in breast adenocarcinoma, lung tumor, stomach, brain, skin and pancreas, and mouse XBP-1S is expressed in mammary tumor, lung tumor metastatic to mammary, and neural retina. Taken together, these data suggest that, like XBP-1U, XBP-1S may play a critical role under physiological and pathological conditions.

Figure 7.

XBP-1 mRNA expression in breast cancer cell lines. RT–PCR from the selected cell lines and cDNA libraries was performed as described in Materials and Methods. β-Actin was used as an internal control.

DISCUSSION

Several recent studies using cDNA microarray analysis have shown that XBP-1 mRNA expression is associated with ERα status in breast tumors (20–25), although the forms of XBP-1 are unknown. This raises at least two possibilities: (i) XBP-1 participates in regulating the ERα promoter or ERα in regulating the XBP-1 promoter; and (ii) XBP-1 interacts with ERα. In this manuscript, we report for the first time that XBP-1 physically and functionally interacts with ERα in a ligand-independent manner. Since XBP-1S and XBP-1U do not bind to the ERE, it is possible that ERα recruits XBP-1 to the ERE-containing promoter to stimulate gene transcription.

ERα has been shown to interact with a number of cofactors, including co-activators and co-repressors (1). Almost all of the co-activators enhance ERα transcriptional activity in a ligand-dependent fashion. They include the SRC-1 family (35), CBP/p300 (36,37), p68 (38), ARA70 (39) and many others (1). In addition to the conventional ligand-dependent regulation of the activity of ERα, ERα has been shown to be activated by non-steroidal agents including dopamine and growth factors (40). This ligand-independent activation is possibly due to the ERα phosphorylation. However, by definition (1), none of the agents are co-activators, as they do not interact with ERα. Cyclin D1 is the first co-activator to have been shown to enhance ERα transactivation in a ligand-independent manner (41–43). Cyclin D1 acts through physical association to activate ERα. To the best of our knowledge, XBP-1 is the second co-activator to enhance ligand-independent ERα transcriptional activation. XBP-1S, the spliced form of XBP-1, is more potent in ERα activation than XBP-1U, the unspliced form of XBP-1. This is consistent with the stronger binding affinity of XBP-1S for ERα both in vitro and in vivo. Effects of antiestrogens on the cyclin D1-induced activation of the ERα are controversial. Neuman et al. have shown that ICI 182,780 and, to a lesser extent, 4-OHT significantly inhibit cyclin D1-mediated activation of the ERα, which is in contrast to the findings of Zwijsen et al. (41,42). In our study, both ICI 182,780 and 4-OHT inhibited the effects of XBP-1 on ERα activity in a similar manner to that reported by Neuman et al.

Co-activators that interact with the DBD of nuclear receptors are less characterized or defined. Our study showed that XBP-1S and XBP-1U interact with the ERα region containing the DBD. Recently, several co-activators that interact with the DBDs of nuclear receptors have been reported, including GT198 (44) and SNURF (45). GT198 interacted with the DBD of glucocorticoid receptor (GR) and potently stimulated transcription mediated by GR. SNURF is a small RING finger protein that co-activates AR-mediated transcription through interaction with the DBD of AR. Since the DBDs of nuclear receptors are highly conserved, we determined the effects of XBP-1U and XBP-1S on AR-mediated transcription. In contrast to the co-activation of ERα by XBP-1S and XBP-1U, XBP-1S decreased transcriptional activity of AR in a cell type-dependent manner, whereas XBP-1U had little effect on AR transcriptional activation (Table 2). This may be exemplified by the cofactor RIP140 (46–50). This cofactor interacts with ERα and increases ERα transcriptional activity in the presence of E2 (46,51). RIP140 has also been shown to act as a co-activator for the rat AR (47). However, recent studies have indicated that RIP140 represses the transcriptional activation of the GR and the orphan nuclear receptor TR2 by interaction with the receptors (48,49). It will be interesting to examine the effects of XBP-1S and XBP-1U on the transcriptional activities of other nuclear receptors.

Although XBP-1 mRNA expression levels have been shown to be elevated during cancer development and progression (20–26), the forms of XBP-1 are unclear. Initially, XBP-1U was thought to be the only form of XBP-1 mRNA expression (14). Recently, it was shown that XBP-1S was expressed in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress (18,19). XBP-1S was also found to be induced during the differentiation of antibody-secreting B cells (50). We report here that XBP-1S mRNA is constitutively expressed in breast cancer cell lines as well as an immortalized human mammary epithelial cell line. Future experiments are required to test whether XBP-1S is expressed in clinical samples. Since the XBP-1 mRNA expression pattern is highly correlated with ERα and highly upregulated in a subset of breast cancers (20–26), XBP-1, especially XBP-1S, may play an important role in breast cancer growth and represent a new target for therapeutic intervention.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Rong Li for sharing reagents, Philip Leder and Fen Zhou for kindly providing the MCF10A, MDA-MB-435, MDA-MB-436, MDA-MB-453, ZR75-1, SKBR3 and BT474 cell lines, and Hsiang-Fu Kung for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by Innovative Grant from AMMS and SRF for ROCS, and Fujian Qian Bai Wan Outstanding Scientist Plan Grant.

REFERENCES

- 1.Klinge C.M. (2000) Estrogen receptor interaction with co-activators and co-repressors. Steroids, 65, 227–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katzenellenbogen B.S. and Katzenellenbogen,J.A. (2000) Estrogen receptor transcription and transactivation: estrogen receptor alpha and estrogen receptor beta: regulation by selective estrogen receptor modulators and importance in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res., 2, 335–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aranda A. and Pascual,A. (2001) Nuclear hormone receptors and gene expression. Physiol. Rev., 81, 1269–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krust A., Green,S., Argos,P., Kumar,V., Walter,P., Bornert,J.M. and Chambon,P. (1986) The chicken oestrogen receptor sequence: homology with v-erbA and the human oestrogen and glucocorticoid receptors. EMBO J., 5, 891–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mangelsdorf D.J., Thummel,C., Beato,M., Herrlich,P., Schutz,G., Umesono,K., Blumberg,B., Kastner,P., Mark,M. and Chambon,P. (1995) The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade, Cell, 83, 835–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuiper G.G., Enmark,E., Pelto-Huikko,M., Nilsson,S. and Gustafsson,J.A. (1996) Cloning of a novel receptor expressed in rat prostate and ovary. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 5925–5930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuiper G.G., Carlsson,B., Grandien,K., Enmark,E., Haggblad,J., Nilsson,S. and Gustafsson,J.A. (1997) Comparison of the ligand binding specificity and transcript tissue distribution of estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Endocrinology, 138, 863–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katzenellenbogen B.S. (1996) Estrogen receptors: bioactivities and interactions with cell signaling pathways. Biol. Reprod., 54, 287–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katzenellenbogen B.S., Montano,M.M., Ekena,K., Herman,M.E. and McInerney,E.M. (1997) Antiestrogens: mechanisms of action and resistance in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat., 44, 23–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robyr D., Wolffe,A.P. and Wahli,W. (2000) Nuclear hormone receptor coregulators in action: diversity for shared tasks. Mol. Endocrinol., 14, 329–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schapira M., Raaka,B.M., Samuels,H.H. and Abagyan,R. (2000) Rational discovery of novel nuclear hormone receptor antagonists. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 1008–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weigel N.L. (1996) Steroid hormone receptors and their regulation by phosphorylation. Biochem. J., 319, 657–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Su L.F., Knoblauch,R. and Garabedian,M.J. (2001) Rho GTPases as modulators of the estrogen receptor transcriptional response. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 3231–3237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liou H.C., Boothby,M.R., Finn,P.W., Davidon,R., Nabavi,N., Zeleznik-Le,N.J., Ting,J.P. and Glimcher,L.H. (1990) A new member of the leucine zipper class of proteins that binds to the HLA DR alpha promoter. Science, 247, 1581–1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clauss I.M., Gravallese,E.M., Darling,J.M., Shapiro,F., Glimcher,M.J. and Glimcher,L.H. (1993) In situ hybridization studies suggest a role for the basic region-leucine zipper protein hXBP-1 in exocrine gland and skeletal development during mouse embryogenesis. Dev. Dyn., 197, 146–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riemold A.M., Etkin,A., Clauss,I., Perkins,A., Friend,D.S., Zhang,J., Horton,H.F., Scott,A., Orkin,S.H., Byrne,M.C., Grusby,M.J. and Glimcher,L.H. (2000) An essential role in liver development for transcription factor XBP-1. Genes Dev., 14, 152–157. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riemold A.M., Iwakoshi,N.N., Manis,J., Vallabhajosyula,P., Szomolanyi-Tsuda,E., Gravallese,E.M., Friend,D., Grusby,M.J., Alt,F. and Glimcher,L.H. (2001) Plasma cell differentiation requires the transcription factor XBP-1. Nature, 412, 300–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshida H., Matsui,T., Yamamoto,A., Okada,T. and Mori,K. (2001) XBP1 mRNA is induced by ATF6 and spliced by IRE1 in response to ER stress to produce a highly active transcription factor. Cell, 107, 881–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calfon M., Zeng,H., Urano,F., Till,J.H., Hubbard,S.R., Harding,H.P., Clark,S.G. and Ron,D. (2002) IRE1 couples endoplasmic reticulum load to secretory capacity by processing the XBP-1 mRNA. Nature, 415, 92–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perou C.M., Sorlie,T., Eisen,M.B., van de Rijn,M., Jeffrey,S.S., Rees,C.A., Pollack,J.R., Ross,D.T., Johnsen,H., Akslen,L.A., Fluge,O., Pergamenschikov,A., Williams,C., Zhu,S.X., Lonning,P.E., Borresen-Dale,A.L., Brown,P.O. and Botstein,D. (2000) Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature, 406, 747–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van't Veer L.J., Dai,H., van de Vijver,M.J., He,Y.D., Hart,A.A., Mao,M., Peterse,H.L., van der Kooy,K., Marton,M.J., Witteveen,A.T., Schreiber,G.J., Kerkhoven,R.M., Roberts,C., Linsley,P.S., Bernards,R. and Friend,S.H. (2002) Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of breast cancer. Nature, 415, 530–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bertucci F., Houlgatte,R., Benziane,A., Granjeaud,S., Adelaide,J., Tagett,R., Loriod,B., Jacquemier,J., Viens,P., Jordan,B., Birnbaum,D. and Nguyen,C. (2000) Gene expression profiling of primary breast carcinomas using arrays of candidate genes. Hum. Mol. Genet., 9, 2981–2991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bertucci F., Nasser,V., Granjeaud,S., Eisinger,F., Adelaide,J., Tagett,R., Loriod,B. Giaconia,A., Benziane,A., Devilard,E., Jacquemier,J., Viens,P., Nguyen,C., Birnbaum,D. and Houlgatte,R. (2002) Gene expression profiles of poor-prognosis primary breast cancer correlate with survival. Hum. Mol. Genet., 11, 863–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iwao K., Matoba,R., Ueno,N., Ando,A., Miyoshi,Y., Matsubara,K., Noguchi,S. and Kato,K. (2002) Molecular classification of primary breast tumors possessing distinct prognostic properties. Hum. Mol. Genet., 11, 199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.West M., Blanchette,C., Dressman,H., Huang,E., Ishida,S., Spang,R., Zuzan,H., Olson,J.A.J., Marks,J.R. and Nevins,J.R. (2001) Predicting the clinical status of human breast cancer by using gene expression profiles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 11462–11467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porter D.A., Krop,I.E., Nasser,S., Sgroi,D., Kaelin,C.M., Marks,J.R., Riggins,G. and Polyak,K. (2001) A SAGE (serial analysis of gene expression) view of breast tumor progression. Cancer Res., 61, 5697–5702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ye Q., Chung,L.W., Cinar,B., Li,S. and Zhau,H.E. (2000) Identification and characterization of estrogen receptor variants in prostate cancer cell lines. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol., 75, 21–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ding X.F., Anderson,C.M., Ma,H., Hong,H., Uht,R.M., Kushner,P.J. and Stallcup,M.R. (1998) Nuclear receptor-binding sites of coactivators glucocorticoid receptor interacting protein 1 (GRIP1) and steroid receptor coactivator 1 (SRC-1): multiple motifs and different binding specificities. Mol. Endocrinol., 12, 302–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cinar B., Koeneman,K.S., Edlund,M., Prins,G.S., Zhau,H.E. and Chung,L.W. (2001) Androgen receptor mediates the reduced tumor growth, enhanced androgen responsiveness and selected target gene transactivation in a human prostate cancer cell line. Cancer Res., 61, 7310–7317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ye Q., Hu,Y.F., Zhong,H., Nye,A.C., Belmont,A.S. and Li,R. (2001) BRCA1-induced large-scale chromatin unfolding and allele-specific effects of cancer-predisposing mutations. J. Cell Biol., 155, 911–921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lazennec G., Bresson,D., Lucas,A., Chauveau,C. and Vignon,F. (2001) ERβ inhibits proliferation and invasion of breast cancer cells. Endocrinology, 142, 4120–4130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ye Q., Chung,L.W., Li,S. and Zhau,H.E. (2000) Identification of a novel FAS/ER-alpha fusion transcript expressed in human cancer cells. Biochim. Biophys Acta, 1493, 373–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klinge C.M. (2000) Estrogen receptor interaction with co-activators and co-repressors. Steroids, 65, 227–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clauss I.M., Chu,M., Zhao,J. and Glimcher,L.H. (1996) The basic domain/leucine zipper protein hXBP-1 preferentially binds to and transactivates CRE-like sequences containg an ACGT core. Nucleic Acids Res., 24, 1855–1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu L., Glass,C.K. and Rosenfeld,M.G. (1999) Coactivator and corepressor complexes in nuclear receptor function. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 9, 140–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chakravarti D., LaMorte,V.J., Nelson,M.C., Nakajima,T., Schulman,I.G., Juguilon,H., Montminy,M. and Evans,R.M. (1996) Role of CBP/p300 in nuclear receptor signalling. Nature, 383, 99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yao T.P., Ku,G., Zhou,N., Scully,R. and Livingston,D.M. (1996) The nuclear hormone receptor coactivator SRC-1 is a specific target of p300. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 10626–10631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Endoh H., Maruyama,K., Masuhiro,Y., Kobayashi,Y., Goto,M., Tai,H., Yanagisawa,J., Metzger,D., Hashimoto,S. and Kato,S. (1999) Purification and identification of p68 RNA helicase acting as a transcriptional coactivator specific for the activation function 1 of human estrogen receptor alpha. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 5363–5372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 39.Alen P., Claessens,F., Schoenmakers,E., Swinnen,J.V., Verhoeven,G., Rombauts,W. and Peeters,B. (1999) Interaction of the putative androgen receptor-specific coactivator ARA70/ELE1alpha with multiple steroid receptors and identification of an internally deleted ELE1beta isoform. Mol. Endocrinol., 13, 117–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weigel N.L. and Zhang,Y. (1998) Ligand-independent activation of steroid hormone receptors. J. Mol. Med., 76, 469–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zwijsen R.M., Wientjens,E., Klompmaker,R., van der Sman,J., Bernards,R. and Michalides,R.J. (1997) CDK-independent activation of estrogen receptor by cyclin D1. Cell, 88, 405–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neuman E., Ladha,M.H., Lin,N., Upton,T.M., Miller,S.J., DiRenzo,J., Pestell,R.G., Hinds,P.W., Dowdy,S.F., Brown,M. and Ewen,M.E. (1997) Cyclin D1 stimulation of estrogen receptor transcriptional activity independent of cdk4. Mol. Cell. Biol., 17, 5338–5347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lamb J., Ladha,M.H., McMahon,C., Sutherland,R.L. and Ewen,M.E. (2000) Regulation of the functional interaction between cyclin D1 and the estrogen receptor. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 8667–8675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ko L., Cardona,G.R., Henrion-Caude,A. and Chin,W.W. (2002) Identification and characterization of a tissue-specific coactivator, GT198, that interacts with the DNA-binding domains of nuclear receptors. Mol. Cell. Biol., 22, 357–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moilanen A.M., Poukka,H., Karvonen,U., Hakli,M., Janne,O.A. and Palvimo,J.J. (1998) Identification of a novel RING finger protein as a coregulator in steroid receptor-mediated gene transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 5128–5139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.L'Horset F., Dauvois,S., Heery,D.M., Cavailles,V. and Parker,M.G. (1996) RIP-140 interacts with multiple nuclear receptors by means of two distinct sites. Mol. Cell. Biol., 16, 6029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ikonen T., Palvimo,J.J and Janne,O.A. (1997) Interaction between the amino- and carboxyl-terminal regions of the rat androgen receptor modulates transcriptional activity and is influenced by nuclear receptor coactivators. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 29821–29828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Subramaniam N. Treuter,E. and Okret,S. (1999) Receptor interacting protein RIP140 inhibits both positive and negative gene regulation by glucocorticoids. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 18121–18127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee C.H., Chinpaisal,C. and Wei,L.N. (1998) Cloning and characterization of mouse RIP140, a corepressor for nuclear orphan receptor TR2. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 6745–6755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gass J.N., Gifford,N.M. and Brewer,J.W. (2002) Activation of an unfolded protein response during differentiation of antibody-secreting B cells. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 49047–49054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cavailles V., Dauvois,S., L’Horset,F., Lopez,G., Hoare,S., Kushner,P.J. and Parker,M.G. (1995) Nuclear factor RIP140 modulates transcriptional activation by the estrogen receptor. EMBO J., 14, 3741–3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]