Abstract

ICP8, the herpes simplex virus type-1 encoded single-strand DNA (ssDNA)-binding protein, promotes the assimilation of a single-stranded DNA molecule into a homologous duplex plasmid resulting in the formation of a displacement loop. Here we examine the mechanism of this process. In contrast to the RecA-type recombinases that catalyze strand invasion via an active search for homology, ICP8 acts by a salt-dependent strand annealing mechanism. The active species in this reaction is a ssDNA:ICP8 nucleoprotein filament. There appears to be no requirement for ICP8 to interact with the acceptor DNA. At higher concentrations, ICP8 promotes the reverse reaction, presumably owing to its helix destabilizing activity. ICP8-mediated strand assimilation imparts single-stranded character onto the acceptor DNA, consistent with the formation of a displacement loop. These data suggest that the recombination activity of ICP8 is similar to the mechanism of eukaryotic Rad52.

INTRODUCTION

The ∼152 kbp linear genome of herpes simplex virus type-1 (HSV-1) is known to undergo prolific recombination (reviewed in 1). Recombination is temporally linked to viral replication (2) and is thought to be responsible for the isomerization of the viral genome as well as generation of highly branched replication intermediates during the viral life cycle (1,3). In addition, recombination may also be required to repair DNA damage that leads to double-strand breaks (DSBs). DSBs may arise as a consequence of replication fork demise at sites of oxidative damage which is known to be induced upon viral infection (4,5). DSBs also arise in replicating DNA due to cleavage of viral a sequences by endonuclease G that may serve in genome isomerization (6,7). The a sequences have also been implicated in circularization of the viral genome by homologous recombination (8). This process occurs immediately following infection by the virus and has been shown to be mediated by host factors (9,10).

High-frequency homologous recombination in HSV-1 occurs in the absence of a viral encoded RecA-like protein. It has been demonstrated that plasmid-based homologous recombination is dependent on replication initiated from the viral origin, oriS (11). Furthermore, this recombination depends solely on the seven essential viral replication genes (11). This complicates the study of viral recombination by genetic analysis since mutations in the genes for replication are rendered unviable. Work from our laboratory has demonstrated that a subset of viral replication proteins have the ability to perform recombination reactions in vitro. Thus, ICP8, the viral single-strand DNA (ssDNA)-binding protein (SSB), in conjunction with the viral encoded helicase-primase, was shown to catalyze strand exchange (12) along the lines of the bacteriophage T7 SSB and helicase-primase (13). Furthermore, ICP8 was shown to promote the assimilation of ssDNA into homologous supercoiled acceptor DNA, resulting in the formation of a displacement loop (D-loop) (14). The invading primer in the D-loop provides a platform for long chain synthesis catalyzed by the viral replication proteins in the presence of a DNA-relaxing enzyme (15). These observations suggest a mechanism whereby recombination-dependent replication accounts for the extensive branching observed during viral replication in vivo (3).

In this work, the ability of ICP8 to promote D-loop formation was examined in greater detail. Our results show that although the product of the ICP8-catalyzed reaction is similar to that formed by the prototypic Escherichia coli recombinase RecA, the mechanism of the two reactions differ. Thus, while RecA promotes ATP-dependent strand invasion, ICP8 relies on its ability to renature the complementary ssDNA molecule, thereby proceeding via a single-strand annealing (SSA) mechanism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Enzymes and reagents

ICP8 was purified as previously described (16). Its concentration, expressed in moles of monomeric protein, was determined using an extinction coefficient of 82 720 M–1 cm–1 at 280 nm, calculated from its predicted amino acid sequence (17). RecA was purchased from United States Biochemical Corp. RecA concentrations are expressed in moles of monomeric protein. Bacteriophage T4 polynucleotide kinase and proteinase K were purchased from New England Biolabs and Roche Molecular Biochemicals, respectively. P1 nuclease, ATP (disodium salt) and chloroquine (diphosphate salt) were purchased from Sigma. One unit of P1 nuclease is that amount of enzyme required to liberate 1 µmol of acid soluble nucleotide from RNA per minute at 37°C and pH 5.3. [γ-32P]ATP (4500 Ci/mmol) was purchased from ICN Biomedicals.

Nucleic acids

Oligodeoxyribonucleotide PB11 (100mer) (18), complementary to residues 379–478 of the minus strand of pUC18, was synthesized and gel purified by Sigma Genosys. Its concentration was determined using an extinction coefficient of 939 208.1 M–1 cm–1 at 260 nm. PB11 was 5′ 32P-labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase and purified using Sephadex G-25 (fine) Quick spin columns (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). M13 and φX174 ssDNA were purchased from New England Biolabs. Unless otherwise stated, pUC18 form I DNA was prepared from E.coli JM109 with the Promega Wizard Plus DNA purification system followed by ethanol precipitation. Alternatively, pUC18 form I was isolated from Brij58-lysed cells followed by anion exchange and gel filtration chromatography [Q high (BioRad) and Chroma Spin + TE-1000 columns (BD Biosciences)]. To mimic the effect induced during alkaline lysis, a portion of this preparation was treated with 0.1 M NaOH, followed by neutralization and extraction with the Promega Wizard Plus DNA purification system and ethanol precipitation. All DNA concentrations are expressed in moles of molecules. The M13:100mer substrate was formed by annealing PB11 (100mer, 1.4 pmol) to M13 ssDNA (0.7 pmol) in the presence 0.1 M NaCl at 95°C for 3 min followed by gradual cooling to <30°C. The un-annealed PB11 was removed by gel filtration through Chroma Spin + TE-1000 columns (BD Biosciences).

D-loop formation

ICP8 (250 nM) was incubated with PB11 (10.5 nM) on ice for 8 min in 25 mM Tris-acetate pH 7.5, 10 mM magnesium acetate, 1 mM DTT and 100 µg/ml BSA to form nucleoprotein filaments. The pairing reaction was initiated by adding pUC18 form I DNA (3.5 nM) and incubation was continued for 30 min at 30°C. Nucleoprotein filaments consisting of RecA (300 nM) and PB11 (10.5 nM) were formed by incubating the two on ice for 8 min in 25 mM Tris-acetate pH 7.5, 10 mM magnesium acetate, 1 mM ATP, 1 mM DTT and 100 µg/ml BSA. The pairing reaction was initiated by adding pUC18 form I DNA (3.5 nM) and incubation was continued for 4 min at 37°C. The reactions were quenched by the addition of termination buffer (final concentration: 50 mM EDTA and 3 µg/µl proteinase K) followed by incubation for 20 min at 30°C. When stated, D-loops were purified using the Promega Wizard DNA clean-up system followed by removal of excess un-annealed PB11 by gel filtration through Biogel A15M (BioRad) in 25 mM Tris-acetate pH 7.5 and 1 mM EDTA. Reaction products were resolved by Tris-acetate EDTA (pH 7.6) agarose gel electrophoresis as stated in the figure legends. Following electrophoresis, the gels were dried onto DE81 chromatography paper (Whatman), analyzed and quantitated by storage phosphor analysis with a Molecular Dynamics Storm 820. Quantitation of D-loop formation is reported after subtracting the protein-independent D-loop reaction from that catalyzed by ICP8. D-loop formation is expressed as a percentage with respect to the concentration of plasmid.

RESULTS

ICP8 and RecA catalyze D-loop formation via distinct mechanisms

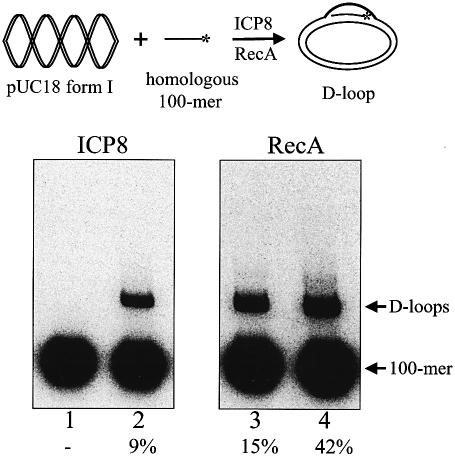

We had previously demonstrated the ability of ICP8 to promote complete assimilation of a 100mer into a homologous form I acceptor plasmid (14). During that study, we observed that the efficiency of strand invasion varied with the batch of pUC18. To determine whether differential exposure to transient denaturing conditions during the preparation of form I DNA (alkaline lysis, phenol–chloroform extraction, alcohol precipitation) contributes towards D-loop formation, we performed reactions using form I that was purified using either denaturing or non-denaturing conditions (see Materials and Methods for purification details). Figure 1 compares the ability of ICP8 and RecA to form D-loops with DNA prepared under non-denaturing conditions and the same DNA that was transiently denatured using alkali. The data show that ICP8 formed D-loops only with the DNA that was briefly exposed to denaturing conditions (Fig. 1, compare lanes 1 and 2). In contrast, RecA formed D-loops with both preparations of DNA (Fig. 1, compare lanes 3 and 4). However, even with RecA, the efficiency of D-loop formation was higher (∼3-fold) with the transiently denatured preparation of DNA. This is presumably because RecA can promote both strand annealing as well as strand invasion reactions with this substrate (19). Consequently, all subsequent experiments used form I acceptor DNA that was purified by exposure to transient denaturing conditions (alkaline lysis). This result suggests that ICP8 does not promote strand invasion along the lines of RecA. Rather, ICP8 relies on the presence of locally denatured DNA to promote assimilation of the donor, thereby indicating that ICP8-mediated D-loop formation proceeds via an SSA mechanism.

Figure 1.

ICP8 and RecA catalyze D-loop formation via distinct mechanisms. ICP8 (lanes 1 and 2) and RecA (lanes 3 and 4) were examined for their ability to form D-loops with pUC18 form I isolated from detergent lysed cells (odd lanes) or the equivalent DNA that had been transiently denatured with alkali followed by purification (even lanes) as described in Materials and Methods. Reactions were resolved by electrophoresis through 0.75% agarose at 8 V/cm for 1.5 h. The positions of D-loops and 100mer are as indicated. The percentage of D-loops formed is indicated below the respective lanes. (Top) A schematic representation of the D-loop reaction.

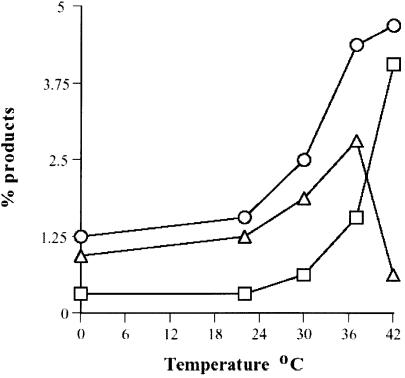

To lend further support to the possible SSA mechanism, we examined whether local ‘opening’ of the acceptor DNA as achieved by thermal denaturation, enhances ICP8-mediated D-loop formation. Thus, the effect of increasing temperature on the efficiency of D-loop formation was determined. Figure 2 shows that the extent of D-loop formation was greater at higher temperatures of incubation. It should be noted that higher temperatures also increased the extent of protein-independent D-loop formation. The biggest difference between ICP8-mediated and spontaneously formed D-loops was observed at 37°C.

Figure 2.

Efficiency of D-loop formation increases with temperature. D-loop reactions were assembled as described in Materials and Methods and incubation was performed at 0, 22, 30, 37 and 42°C. Reactions were resolved by electrophoresis through 0.75% agarose at 8 V/cm for 1.5 h and D-loop formation was quantitated. ICP8 reactions (circles), protein independent reactions (squares) and the corrected values (triangles).

An ssDNA:ICP8 nucleoprotein filament is the active species during D-loop formation

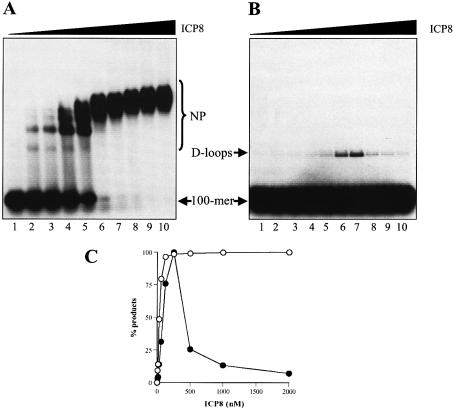

To further understand the mechanism of D-loop formation, we examined the interaction of ICP8 with donor and acceptor DNA. In the first experiment, increasing concentrations of ICP8 were incubated with the donor DNA to allow nucleoprotein filament formation (Fig. 3A and C). The amount of ICP8 required to completely coat the 100mer was 250 nM. This amount corresponds to a 2.5-fold excess over the coating concentration, assuming a site size of 10 ± 1 nt (20) and that 100% of the protein was active. Importantly, maximal D-loop formation occurred at the same concentration of ICP8 (Fig. 3B and C). Although higher ICP8 concentrations yielded robust nucleoprotein filaments, the efficiency of D-loop formation decreased (Fig. 3B and C). To determine whether optimal D-loop formation required the interaction of the excess ICP8 with acceptor DNA, the extra ICP8 was sequestered by the addition of a 5-fold excess of φX174 ssDNA following the formation of nucleoprotein filaments. Acceptor DNA was then added to initiate the pairing reaction. Figure 4 shows that removal of the excess ICP8 did not affect the efficiency of D-loop formation [compare lanes 4 (3.45% D-loops) and 5 (4% D-loops)]. Moreover, nucleoprotein formation was not significantly affected (Fig. 4, compare lanes 1 and 2). Also, pre-incubation of acceptor DNA with ICP8 followed by the addition of ssDNA did not influence D-loop formation (data not shown). Thus, an interaction between ICP8 and the acceptor DNA does not appear to be necessary to enhance the pairing reaction.

Figure 3.

An ssDNA:ICP8 nucleoprotein filament is the active species in D-loop formation. PB11 was incubated with increasing ICP8 concentrations as described in Materials and Methods. One half of each reaction was immediately subjected to electrophoresis without termination to determine nucleoprotein filament formation. The other half was supplemented with pUC18 form I to allow for D-loop formation and incubated as described followed by electrophoresis through 0.75% agarose at 4.5 V/cm for 3.5 h. (A) Storage phosphor image showing nucleoprotein filament formation. Lanes 1–10, reactions with 0, 7.5, 15, 30, 60, 125, 250, 500, 1000 and 2000 nM ICP8, respectively. (B) Storage phosphor image showing D-loop formation. Lanes 1–10, reactions with 0, 7.5, 15, 30, 60, 125, 250, 500, 1000 and 2000 nM ICP8, respectively. (C) Quantitation of nucleoprotein filaments (open circles) and D-loop formation (closed circles). Values are expressed as a percentage of maximal activity (97% for nucleoprotein filaments and 4% for D-loops). The positions of D-loops, nucleoprotein filaments (NP) and 100mer are as indicated.

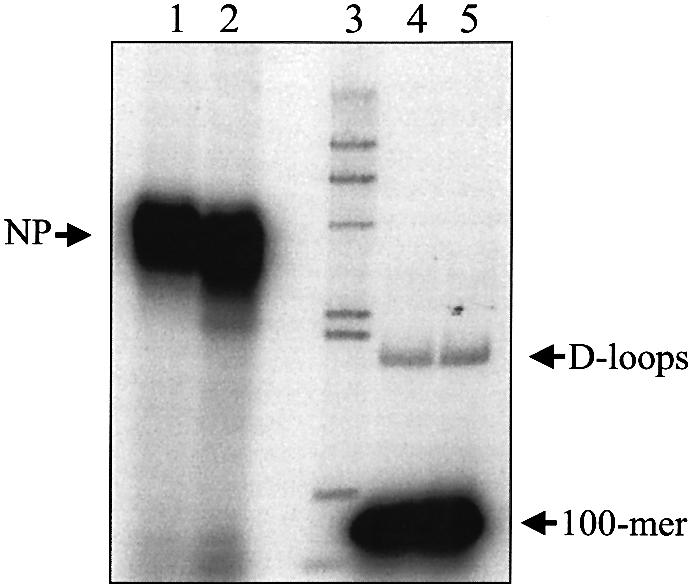

Figure 4.

Competitor ssDNA has no effect on nucleoprotein filament or D-loop formation. PB11 was incubated with ICP8 as described in Materials and Methods to form nucleoprotein filaments. The nucleoprotein filaments were further processed as follows. Reaction 1 was immediately subjected to electrophoresis without termination to determine nucleoprotein filament formation (lane 1). Reaction 2 was supplemented with 7.5 µM φX174 DNA and incubated for an additional 8 min on ice followed by electrophoresis without termination (lane 2). Reactions 3 and 4 were treated similarly to reactions 1 and 2 except that they were supplemented with pUC18 form I to allow D-loop formation (lanes 4 and 5). Reactions were resolved by electrophoresis through 0.75% agarose at 8 V/cm for 1.5 h. The positions of D-loops, nucleoprotein filaments (NP) and 100mer are as indicated. Lane 3 depicts the migration of 32P-labeled λ-HindIII fragments.

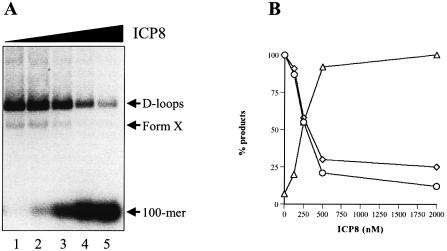

D-loops are destabilized at high ICP8 concentrations

To examine the possibility that D-loops are disrupted at higher ICP8 concentrations (see Fig. 3B and C), purified D-loops were incubated with increasing concentrations of ICP8. Reaction products were analyzed by electrophoresis through a chloroquine-containing agarose gel which permits separation of D-loops from a more positively supercoiled form of D-loops, called form X (14). Figure 5 shows that increasing concentrations of ICP8 resulted in the disappearance of D-loops with the concomitant release of the 100mer. Approximately 50% of the D-loops were unwound at 250 nM. This corresponds to a 5-fold excess of ICP8 over that required to coat all the DNA on the plasmid that underwent D-loop formation, based on a site size of 10 ± 1 nt (20). Dissociation of form X followed similar kinetics (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

D-loops are destabilized at high ICP8 concentrations. Purified D-loops (∼0.1 nM) were incubated with increasing concentrations of ICP8 for 30 min at 30°C in 25 mM Tris-acetate pH 7.5, 1 mM DTT and 100 µg/ml BSA. Reaction products were resolved by electrophoresis through 1% agarose containing 25 µg/ml chloroquine at 4.5 V/cm for 3 h. (A) Storage phosphor image. Lanes 1–5, 0, 125, 250, 500 and 2000 nM ICP8, respectively. (B) Quantitation of the data in (A). D-loops (circles), form X (diamonds) and 100mer (triangles). The positions of D-loops, form X and 100mer are as indicated.

Properties of ICP8-catalyzed D-loop formation

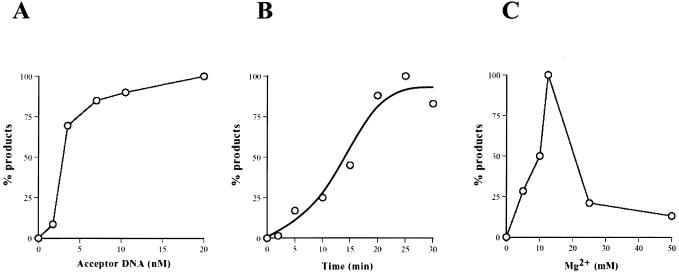

The properties of ICP8-catalyzed D-loop formation are depicted in Figure 6. To determine the optimal concentration of acceptor DNA, the concentration of acceptor DNA was varied while keeping the donor DNA concentration constant at 10.5 nM (Fig. 6A). The data show that D-loop formation initially increased with increasing amounts of acceptor DNA. At higher acceptor DNA concentrations (>10 nM), product formation ceased to increase presumably because the amount of nucleoprotein filament becomes limiting. The time course indicates that D-loop formation plateaus after 30 min, the standard incubation time of our experiments (Fig. 6B). Figure 6C shows the dependence of D-loop formation on Mg2+, with an optimum at 15 mM. Higher concentrations of Mg2+ (>15 mM) inhibited D-loop formation, probably due to stabilization of duplex DNA, thereby essentially preventing intermolecular pairing.

Figure 6.

Properties of ICP8-mediated D-loop formation. D-loops were formed with ICP8 as described in Materials and Methods, followed by electrophoresis through 0.75% agarose at 8 V/cm for 1.5 h. Quantitation of D-loop formation as functions of acceptor DNA concentration (A), time (B) and Mg2+ concentration (C). Values are expressed as a percentage of maximal activity for each variable [1.2% (with respect to ssDNA) for acceptor DNA, 1.8% for time and 3.6% for Mg2+].

ICP8-catalyzed D-loop formation imparts single-stranded character onto the acceptor DNA

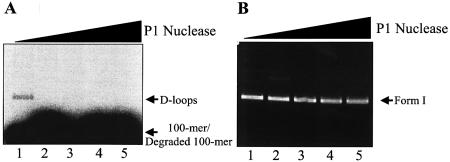

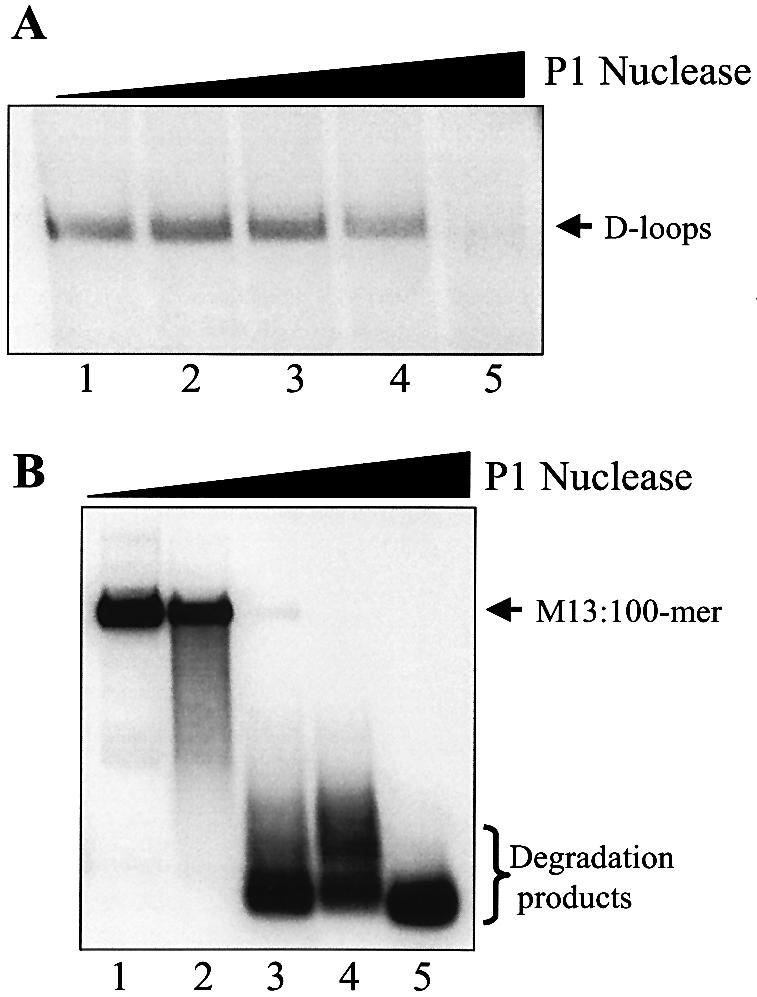

To determine whether strand assimilation imparts single-stranded character onto the acceptor plasmid, D-loops were subjected to P1 nuclease, an ssDNA-specific endonuclease. Figure 7 shows whereas D-loops were sensitive to P1, form I DNA that did not participate in the D-loop reaction was resistant, thereby indicating that D-loops possess a different degree of single-stranded character as compared with the acceptor DNA molecule. We had earlier determined that the donor 100mer undergoes Watson–Crick base-pairing with the complementary strand of the acceptor DNA, presumably resulting in the displacement of the non- complementary strand (14). The susceptibility of the D-loops towards P1 nuclease provides additional support to this notion since the displaced single-stranded region would be vulnerable to incision.

Figure 7.

ICP8-promoted D-loops exhibit single-stranded character. D-loops were formed as described in Materials and Methods, treated with increasing amounts of P1 nuclease for 2 min at room temperature and resolved by electrophoresis through 0.75% agarose at 8 V/cm for 1.5 h. (A) and (B) are storage phosphor and ethidium bromide-stained images of the same gel, respectively. Lanes 1–5, 0, 2, 5, 10 and 20 µunits of P1 nuclease. The positions of form I, D-loops, 100mer and degraded 100mer are as indicated.

To ascertain whether D-loops possess extensive single-stranded character, we compared the P1 nuclease susceptibility of purified D-loops to M13 ssDNA to which the same 100mer (PB11) was annealed (M13:100mer). The M13: 100mer substrate is theoretically equivalent to a D-loop in which base-pairing in the body of the plasmid is completely disrupted, i.e. it possesses maximum single-stranded character. Thus, while degradation of M13:100mer was already evident with 0.05 µunits (Fig. 8B, lane 2), degradation of D-loops was only observed with 5 µunits (Fig. 8A, lane 5), thereby indicating that D-loops are not predominantly single stranded.

Figure 8.

Comparison of cleavage kinetics of D-loops and ssDNA by P1 nuclease. D-loops (3.5 nM) and M13:100mer (3.5 nM) were formed as described in Materials and Methods, treated with increasing amounts of P1 nuclease for 2 min at room temperature and resolved by electrophoresis through 0.75% agarose at 8 V/cm for 1.5 h. (A) Lanes 1–5, D-loops treated with 0, 0.05, 0.5, 1 and 5 µunits of P1 nuclease. (B) Lanes 1–5, M13:100mer treated with 0, 0.05, 0.5, 1 and 5 µunits of P1 nuclease. The positions of D-loops, M13ssDNA:100mer and degradation products are as indicated.

DISCUSSION

ICP8 exhibits several thermodynamic properties that more closely resemble those of recombinases (e.g. RecA and T4 UvsX) than those of other SSBs (20). These include its ability to stretch ssDNA, formation of stable complexes with ssDNA at high salt concentrations, relatively low-affinity ssDNA binding and weak cooperativity (20). Indeed, using a classical in vitro assay, we demonstrated that ICP8 promotes assimilation of ssDNA into a homologous plasmid, resulting in the formation of a D-loop (14). The products of this reaction are the same as those formed by the action of the prototypic E.coli recombinase RecA. However, the reaction mechanism appeared to be different primarily because it occurred in the absence of ATP (14). Moreover, we showed that the ICP8 reaction proceeded only with form I as acceptor DNA (14). This led us to conclude that ICP8 may utilize the energy stored in the superhelical acceptor DNA to drive the reaction.

To gain further insight into the mechanistic differences between the RecA- and ICP8-mediated reactions, we compared the ability of ICP8 and RecA to form D-loops using acceptor DNA that was purified using non-denaturing conditions or by transient denaturation (alkaline lysis). The reasoning was to determine whether brief exposure to denaturing conditions contributes towards D-loop formation. Our results show that although RecA could promote ‘invasion’ of ssDNA into either acceptor DNA, ICP8 could only promote assimilation of ssDNA into the transiently denatured acceptor DNA. Plasmids purified by alkaline lysis possess stretches of denatured DNA that may be used by ICP8 to promote intermolecular pairing. This indicates that the ICP8-mediated reaction proceeds via an SSA mechanism. We previously commented on the inefficiency of the ICP8-catalyzed reaction relative to that mediated by RecA (14). It is possible that this is due to the presence of suitably denatured acceptor regions in only a fraction of the plasmid molecules.

A nucleoprotein filament consisting of ICP8 and the donor 100mer is the active species in the reaction. Maximum D-loop formation was observed at the lowest concentration of ICP8 that yielded 100% nucleoprotein filaments. This concentration corresponds to a 2.5-fold excess over that required to coat all molecules of 100mer, based on a site size of 10 ± 1 nt (20). In theory, coating concentrations of ICP8 should suffice for 100% nucleoprotein filament formation. This apparent discrepancy may be due to the fact that a fraction of ICP8 is inactive or due to an overestimation of its concentration. It is also possible that excess concentrations of ICP8 are required for an interaction with the acceptor DNA. To address this notion, we performed an experiment in which the excess ICP8 was sequestered by the addition of heterologous competitor ssDNA. This experiment showed that removal of the excess ICP8 did not affect the efficiency of nucleoprotein filament or D-loop formation, thereby indicating that ICP8 does not need to interact with and destabilize the acceptor DNA to facilitate D-loop formation. Supersaturating concentrations of ICP8 were seen to decrease D-loop formation. We speculated that at higher concentrations, the helix-destabilizing activity of ICP8 (21) would dominate over the pairing activity (22), thereby resulting in destruction of D-loops. This view was supported by the observation that ICP8 does indeed catalyze the reverse reaction leading to the release of the assimilated 100mer from purified D-loops. The requirement for ICP8 concentrations in excess of those required to coat the DNA may be attributed to the fact that either only a portion of ICP8 was active and/or reaction conditions were not optimal.

The standard incubation conditions for the pairing reaction were 30°C for 30 min. Although the efficiency of D-loop formation increased with temperature, higher temperatures also enhanced spontaneous D-loop formation. Therefore, reactions were performed at 30°C to keep the spontaneous reaction at a minimum. Incubation times longer than 30 min did not increase the efficiency of D-loop formation, possibly because an equilibrium between the forward and reverse reactions is established, or because acceptor plasmid that contains suitably denatured regions becomes limiting. D-loop formation is salt-dependent (Mg2+), although at higher concentrations, Mg2+ is inhibitory. Divalent salts are known to stabilize duplex DNA and higher concentrations would presumably impede D-loop formation.

The donor DNA undergoes Watson–Crick base-pairing with the complementary region of the acceptor plasmid (14). This was demonstrated by the susceptibility of D-loops to restriction endonucleases that cleave within the region of pairing (14). This result indicates that D-loops do not exist in a triple-helical state, since such a structure is known to resist cleavage by restriction endonucleases (23). Pairing between the donor and complementary acceptor strands is thought to displace the non-complementary strand, resulting in a D-loop. The observation that the products of ICP8-catalyzed strand assimilation are sensitive to P1 nuclease supports the existence of a displaced non-complementary strand, i.e. a D-loop. The fact that D-loops do not possess extensive single-stranded character is demonstrated by the differential susceptibility of M13:100mer, an artificially constructed substrate that would represent a D-loop with maximum single-stranded character, and D-loops towards P1 nuclease. Whereas the lowest amount of P1 nuclease tested was sufficient to degrade M13:100mer, D-loops required 100-fold more enzyme for cleavage.

In summary, our studies show that the mechanism whereby ICP8 catalyzes recombination reactions is distinct to that of bona fide recombinases such as E.coli RecA, in as much as ICP8 acts by an SSA mechanism (24). In this respect, ICP8 is similar to Rad52, the eukaryotic SSA protein (25). As yet, the crystal structure of ICP8 has not been solved. In addition, the amino acid sequence of ICP8 is unique and lacks homology to other SSBs. These facts as well as the lethality of ICP8 mutants has made identification of active residues difficult. Recently, a mutant form of T7 gene 2.5 protein (R82C) was reported that lacked DNA annealing activity (26). Identific ation of a similar mutant of ICP8 would help to delineate the contributions of the protein during recombination in vivo.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants GM62643 from the National Institutes of Health and BM 022 from the Florida Biomedical Research Program to P.E.B.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boehmer P.E. and Nimonkar,A.V. (2003) Herpes virus replication. IUBMB Life, 55, 13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dutch R.E., Bruckner,R.C., Mocarski,E.S. and Lehman,I.R. (1992) Herpes simplex virus type 1 recombination: role of DNA replication and viral a sequences. J. Virol., 66, 277–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Severini A., Scraba,D.G. and Tyrrell,D.L. (1996) Branched structures in the intracellular DNA of herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol., 70, 3169–3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valyi-Nagy T., Olson,S.J., Valyi-Nagy,K., Montine,T.J. and Dermody,T.S. (2000) Herpes simplex virus type 1 latency in the murine nervous system is associated with oxidative damage to neurons. Virology, 278, 309–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milatovic D., Zhang,Y., Olson,S.J., Montine,K.S., Roberts,L.J.,II, Morrow,J.D., Montine,T.J., Dermody,T.S. and Valyi-Nagy,T. (2002) Herpes simplex virus type 1 encephalitis is associated with elevated levels of F2-isoprostanes and F4-neuroprostanes. J. Neurovirol., 8, 295–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wohlrab F., Chatterjee,S. and Wells,R.D. (1991) The herpes simplex virus 1 segment inversion site is specifically cleaved by a virus-induced nuclear endonuclease. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 88, 6432–6436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang K.J., Zemelman,B.V. and Lehman,I.R. (2002) Endonuclease G, a candidate human enzyme for the initiation of genomic inversion in herpes simplex type 1 virus. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 21071–21079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yao X.D., Matecic,M. and Elias,P. (1997) Direct repeats of the herpes simplex virus a sequence promote nonconservative homologous recombination that is not dependent on XPF/ERCC4. J. Virol., 71, 6842–6849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garber D.A., Beverley,S.M. and Coen,D.M. (1993) Demonstration of circularization of herpes simplex virus DNA following infection using pulsed field gel electrophoresis. Virology, 197, 459–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yao X.D. and Elias,P. (2001) Recombination during early herpes simplex virus type 1 infection is mediated by cellular proteins. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 2905–2913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weber P.C., Challberg,M.D., Nelson,N.J., Levine,M. and Glorioso,J.C. (1988) Inversion events in the HSV-1 genome are directly mediated by the viral DNA replication machinery and lack sequence specificity. Cell, 54, 369–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nimonkar A.V. and Boehmer,P.E. (2002) In vitro strand exchange promoted by the herpes simplex virus type-1 single strand DNA-binding protein (ICP8) and DNA helicase-primase. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 15182–15189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kong D. and Richardson,C.C. (1996) Single-stranded DNA binding protein and DNA helicase of bacteriophage T7 mediate homologous DNA strand exchange. EMBO J., 15, 2010–2019. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nimonkar A.V. and Boehmer,P.E. (2003) The herpes simplex virus type-1 single-strand DNA-binding protein (ICP8) promotes strand invasion. J. Biol. Chem., 278, 9678–9682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nimonkar A.V. and Boehmer,P.E. (2003) Reconstitution of recombination-dependent DNA synthesis in herpes simplex virus type-1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 100, 10201–10206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boehmer P.E. and Lehman,I.R. (1993) Physical interaction between the herpes simplex virus 1 origin-binding protein and single-stranded DNA-binding protein ICP8. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 90, 8444–8448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gill S.C. and von Hippel,P.H. (1989) Calculation of protein extinction coefficients from amino acid sequence data. Anal. Biochem., 182, 319–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boehmer P.E., Dodson,M.S. and Lehman,I.R. (1993) The herpes simplex virus type-1 origin binding protein. DNA helicase activity. J. Biol. Chem., 268, 1220–1225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muller B. and Stasiak,A. (1991) RecA-mediated annealing of single-stranded DNA and its relation to the mechanism of homologous recombination. J. Mol. Biol., 221, 131–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gourves A.S., Tanguy Le Gac,N., Villani,G., Boehmer,P.E. and Johnson,N.P. (2000) Equilibrium binding of single-stranded DNA with herpes simplex virus type I-coded single-stranded DNA-binding protein, ICP8. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 10864–10869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boehmer P.E. and Lehman,I.R. (1993) Herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP8: helix-destabilizing properties. J. Virol., 67, 711–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dutch R.E. and Lehman,I.R. (1993) Renaturation of complementary DNA strands by herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP8. J. Virol., 67, 6945–6949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanvey J.C., Shimizu,M. and Wells,R.D. (1990) Site-specific inhibition of EcoRI restriction/modification enzymes by a DNA triple helix. Nucleic Acids Res., 18, 157–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mazin A.V., Zaitseva,E., Sung,P. and Kowalczykowski,S.C. (2000) Tailed duplex DNA is the preferred substrate for Rad51 protein-mediated homologous pairing. EMBO J., 19, 1148–1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shinohara A., Shinohara,M., Ohta,T., Matsuda,S. and Ogawa,T. (1998) Rad52 forms ring structures and co-operates with RPA in single-strand DNA annealing. Genes Cells, 3, 145–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rezende L.F., Willcox,S., Griffith,J.D. and Richardson,C.C. (2003) A single-stranded DNA-binding protein of bacteriophage T7 defective in DNA annealing. J. Biol. Chem., May 14 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]