Abstract

Evi-1 encodes a nuclear protein involved in leukemic transformation of hematopoietic cells. Evi-1 possesses two sets of zinc finger motifs separated into two domains, and its characteristics as a transcriptional regulator have been described. Here we show that Evi-1 acts as an inhibitor of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), a class of mitogen-activated protein kinases implicated in stress responses of cells. Evi-1 physically interacts with JNK, although it does not affect its phosphorylation. This interaction is required for inhibition of JNK. Evi-1 protects cells from stress-induced cell death with dependence on the ability to inhibit JNK. These results reveal a novel function of Evi-1, which provides evidence for inhibition of JNK by a nuclear oncogene product. Evi-1 blocks cell death by selectively inhibiting JNK, thereby contributing to oncogenic transformation of cells.

Keywords: apoptosis/Evi-1/JNK/zinc fingers

Introduction

Evi-1 was first identified as a gene existing in a common locus of retroviral integration in myeloid tumors in AKXD mice (Mucenski et al., 1988). This gene encodes a 145 kDa nuclear-localized protein, which possesses seven and three repeats of zinc finger motifs separated into two clusters (Morishita et al., 1988, 1990). The human Evi-1 gene is located on chromosome 3q26, and rearrangements involving this region often activate Evi-1 expression in myeloid leukemia and myelodysplasia (Morishita et al., 1992b; Levy et al., 1994; Ogawa et al., 1996a; Peeters et al., 1997), although its expression is barely detectable in normal bone marrow and peripheral blood. In t(3;21)(q26;q22), found in cases with blastic crisis of chronic myelogenous leukemia, we have reported that Evi-1 is fused to the AML1 gene and is transcriptionally activated as the AML1–Evi-1 chimera (Mitani et al., 1994). Many lines of evidence suggest a critical role for Evi-1 in t(3;21) leukemogenesis (Tanaka et al., 1994, 1995; Kurokawa et al., 1995, 1998a,b). Elevated expression of Evi-1 also occurs without cytogenetically evident translocations in some myeloid malignancies (Russell et al., 1994; Ogawa et al., 1996b). These facts indicate that Evi-1 has a pivotal role in malignant transformation of hematopoietic cells as a dominant oncogene.

Thus far, characteristics of Evi-1 as a transcriptional regulator have been described (Lopingco and Perkins, 1996; Bartholomew et al., 1997). We reported that Evi-1 elevates intracellular AP-1 activity and stimulates the c-fos promoter with dependence on the second zinc finger domain (Tanaka et al., 1994). With regard to the biological effects of Evi-1, it is known that overexpressed Evi-1 can disturb hematopoietic cell differentiation (Morishita et al., 1992a; Kreider et al., 1993). We have reported that Evi-1 causes cellular transformation when overexpressed in Rat-1 fibroblast cells (Kurokawa et al., 1995) and that it antagonizes the growth-inhibitory effects of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) by inhibiting Smad3 (Kurokawa et al., 1998a,b). Available evidence suggests that Evi-1 potentially possesses abilities for growth promotion and differentiation block in some types of cells.

Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase cascades are universal signal transduction modules that are used in a wide variety of biological response mechanisms (Davis, 1993). In vertebrates, at least three such pathways have been identified, which activate different MAP kinase classes, known as ERK, JNK and p38 (Treisman, 1996; Robinson and Cobb, 1997). Among MAP kinases, JNK (also known as SAPK) is activated preferentially by extracellular stress stimuli including UV light, γ-radiation, osmotic shock, protein synthesis inhibitors, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-1 (Derijard et al., 1994; Kyriakis et al., 1994; Kharbanda et al., 1995; Chen et al., 1996a; Fanger et al., 1997). Whereas ERK signaling is generally involved in the control of cell proliferation and differentiation, recent evidence suggests that the JNK pathway may play an important role in triggering apoptosis in response to cellular stresses (Xia et al., 1995; Chen et al., 1996a; Verheij et al., 1996; Zanke et al., 1996).

JNK activation requires phosphorylation at two residues, Thr183 and Tyr185, by MKK4 (also called SEK1 or MEK4) (Sanchez et al., 1994; Derijard et al., 1995; Lin et al., 1995) or MKK7 (Holland et al., 1997; Moriguchi et al., 1997; Tournier et al., 1997), which are dual specificity protein kinases. Like ERKs, the activated JNKs translocate into the nucleus where they phosphorylate transcription factors such as c-Jun (Derijard et al., 1994) and strongly augment their transcriptional activity. While several nuclear transcription factors exhibit alterations in their function depending on phosphorylation by activated MAP kinases, regulatory mechanisms that modify the activities of MAP kinases in the nucleus are not well understood. In the present study, we demonstrate that Evi-1 suppresses JNK activity, thus preventing cellular death induced by stress stimuli. Identification of Evi-1 as a regulator of JNK activity provides a novel function for a nuclear oncoprotein, and proposes a novel mechanism through which Evi-1 contributes to malignant transformation of cells.

Results

Evi-1 inhibits JNK activity

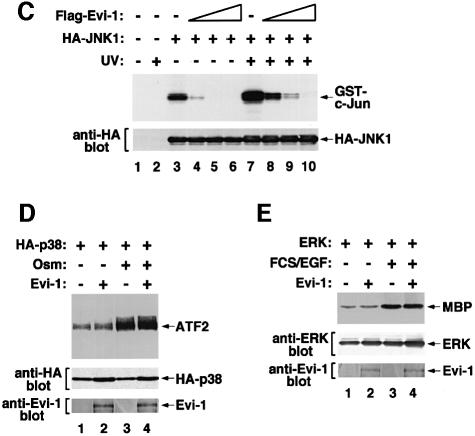

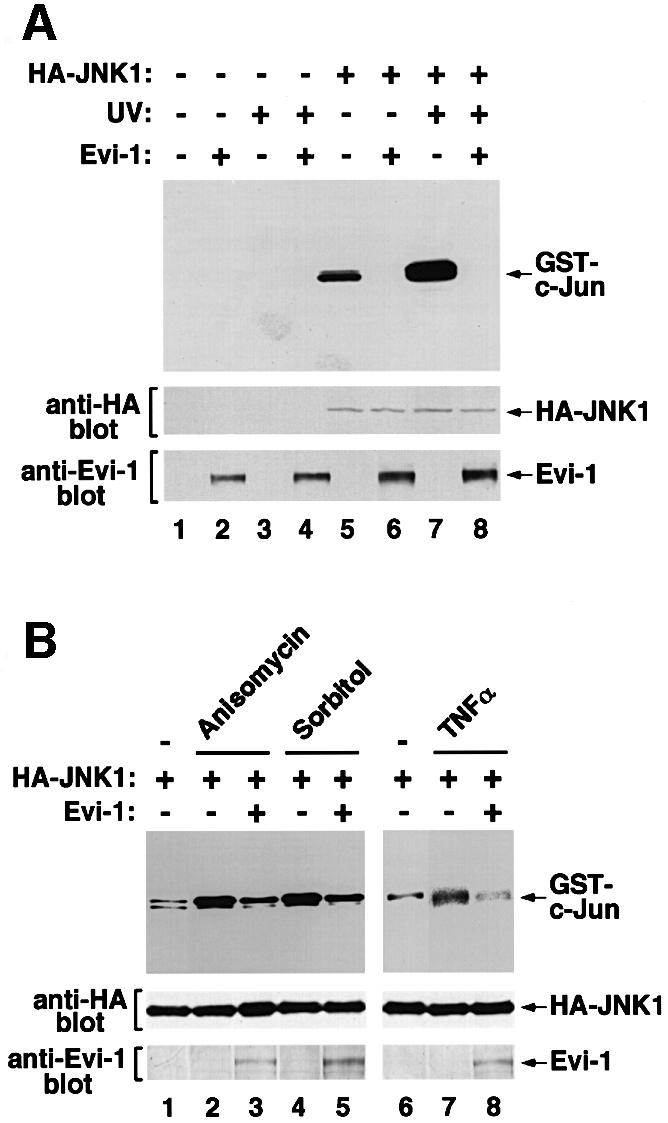

To examine the potential role of Evi-1 in regulating JNK signal transduction, we evaluated the effect of Evi-1 on the kinase activity of JNK. Hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged JNK1 was expressed either alone or with Evi-1 in COS7 cells. The cells were exposed to UV, and JNK1 activity was measured by immunoprecipitation followed by in vitro kinase assay using GST–c-Jun as a substrate. In the absence of Evi-1, phosphorylation of GST–c-Jun by JNK1 is enhanced efficiently after UV stimulation (Derijard et al., 1994) (Figure 1A). However, Evi-1 significantly suppressed JNK1 activity when they were co-expressed. JNK is also known to be activated in response to the protein synthesis inhibitor anisomycin, sorbitol-induced osmolarity changes and treatment with TNF-α. Consistent with previous observations, these reagents effectively activated JNK1 expressed in COS7 cells (Figure 1B). All of these effects were again inhibited when Evi-1 was present, indicating that Evi-1 can suppress JNK activity induced by a wide variety of stimuli. To test whether Evi-1 can inhibit JNK in vitro, Flag-tagged Evi-1 was expressed in COS7 cells, recovered on protein G–Sepharose conjugated with the anti-Flag antibody (M2; Sigma) and eluted with the Flag peptide. Then it was added to the precipitates including HA-JNK1 in increasing doses, and JNK1 activity was measured. As shown in Figure 1C, Flag-Evi-1 inhibited JNK activity in a dose-dependent manner. These results suggest that JNK inhibition by Evi-1 does not require intricate pathways that are possible only in intact cells, although they do not preclude the need for accessory molecules. Kinase assays were also performed with p38, another mammalian MAP kinase that can be activated by cellular stresses (Han et al., 1994), and with ERK. In contrast to JNK1, Evi-1 did not inhibit the activity of p38 (Figure 1D). The kinase activity of ERK was also little affected by Evi-1 (Figure 1E). These results indicate that Evi-1 specifically inhibits JNK activity.

Fig. 1. (A and B) Effects of Evi-1 on JNK activation by cellular stresses. (A) pSRα-HA-JNK1 was transfected into COS7 cells either alone or together with pME18S-Evi-1, and the cells were treated with 60 J/m2 UV. HA-JNK1 was isolated by immunoprecipitation, and its activity was measured by phosphorylation of the substrate GST–c-Jun(1–79) using SDS–PAGE (top). Expression of JNK1 and Evi-1 is shown (middle and bottom). (B) COS7 cells transfected with pSRα-HA-JNK1 either alone or together with pME18S-Evi-1 were treated with 0.5 M sorbitol, 10 µg/ml anisomycin or 5 nM TNFα. HA-JNK1 was isolated by immunoprecipitation with 12CA5, and subjected to the kinase assay (top). Expression of HA-JNK1 was monitored (bottom). (C) Evi-1 inhibits JNK1 activity in vitro. COS7 cells introduced with HA-JNK1 were either left untreated or treated with 60 J/m2 UV. HA-JNK1 was immunoprecipitated, incubated with increasing doses of Flag-Evi-1 isolated from COS7 cells and subjected to the kinase assay (top). Expression of HA-JNK1 was monitored (bottom). (D and E) Activities of p38 and ERK in the presence of Evi-1. HA-p38 or ERK was expressed in COS7 cells either alone or together with Evi-1, and the cells were treated with 0.7 M NaCl or FCS plus epidermal growth factor (EGF), respectively. HA-p38 or ERK was immunoprecipitated with 12CA5 or αC92, and subjected to kinase assays using ATF2 or MBP as a substrate (top). Expression of each protein was monitored (middle and bottom).

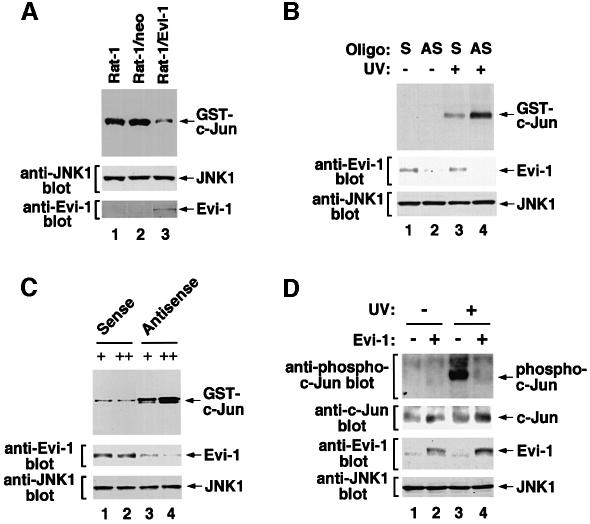

Next, we tested the effect of Evi-1 on endogenous JNK activity. We introduced Evi-1 into Rat-1 cells by retroviral infection and exposed them to UV. As shown in Figure 2A, JNK1 activity was significantly suppressed in the Rat-1 cells stably expressing Evi-1. We investigated further whether the naturally expressed Evi-1 also inhibits JNK activity. MOLM-1 cells, a human megakaryoblastoid cell line that uniquely expresses a truncated form of Evi-1 (Ogawa et al., 1996a), were treated with an antisense oligonucleotide complementary to the sequence encoding the N-terminus of the first zinc finger domain of Evi-1. As shown in Figure 2B, endogenous Evi-1 expression in MOLM-1 cells was reduced effectively by treatment with the antisense oligonucleotide, as compared with the corresponding sense oligonucleotide. Expression of endogenous JNK1 remained unchanged in the presence of either oligonucleotide. We determined the UV-induced activity of endogenous JNK1 in these cells, and found that JNK1 activity was restored when expression of endogenous Evi-1 was repressed (Figure 2B). Similar experiments were performed with HEC1B cells, a human endometrial carcinoma cell line that expresses Evi-1 at a high level (Morishita et al., 1990). When Evi-1 expression was reduced by antisense inhibition with different doses of oligonucleotide, the endogenous JNK1 activity was recovered with dependence on expression levels of Evi-1 (Figure 2C). Taking these results together, we can conclude that Evi-1 inhibits endogenous JNK activity in both non-hematopoietic and hematopoietic cells. We next examined whether Evi-1 affects phosphorylation of endogenous substrates as a result of JNK inhibition. To this end, we introduced Evi-1 into NIH 3T3 cells, and evaluated the amount of phosphorylated c-Jun in these cells. Phosphorylation of c-Jun was clearly detected in response to UV stimulation in the mock-infected cells using the antibody specific to phosphorylated c-Jun (Figure 2D). This phosphorylation was reduced significantly in the Evi-1-expressing cells, while the amount of endogenous c-Jun was little affected regardless of Evi-1 expression or UV stimulation. These results suggest that Evi-1 can reduce phosphorylation of the endogenous substrate for JNK in vivo.

Fig. 2. Evi-1 inhibits endogenous JNK activity. (A) Evi-1 was introduced into Rat-1 cells by retroviral infection, and the cells were treated with 300 J/m2 UV. Endogenous JNK1 was immunoprecipitated with anti-JNK1, and the kinase assay was performed (top). Samples from the parental and the mock-infected Rat-1 cells are shown (lanes 1 and 2). Expression of endogenous JNK1 and retrovirally introduced Evi-1 was monitored (middle and bottom). (B) MOLM-1 cells were treated with 5 µg of the sense (S) or antisense (AS) oligonucleotide for Evi-1, and then treated with 100 J/m2 UV. Endogenous JNK1 was then immunoprecipitated with anti-JNK1 and subjected to the kinase assay (top). Expression of endogenous Evi-1 and JNK1 was determined (middle and bottom). (C) HEC1B cells were treated with 0.1 (+) or 5 µg (++) of the sense or antisense oligonucleotide for Evi-1, and treated with 100 J/m2 UV. Then endogenous JNK1 was immunoprecipitated with anti-JNK1 and subjected to the kinase assay (top). Expression of endogenous Evi-1 and JNK1 was determined (middle and bottom). (D) Evi-1 was introduced into NIH 3T3 cells by retroviral infection, and the cells were treated with 80 J/m2 UV. Whole-cell extracts were subjected to SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted with the phospho-c-Jun antibody, anti-c-Jun, anti-Evi-1 or anti-JNK1 as indicated.

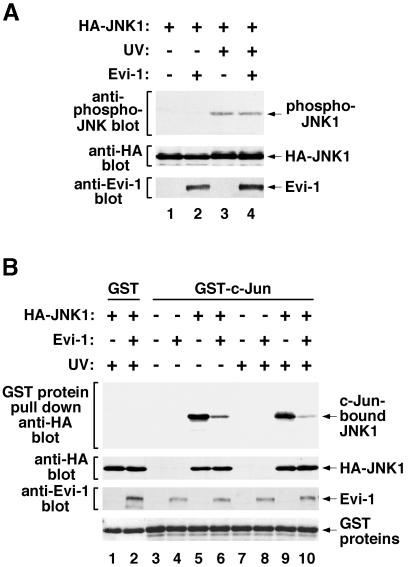

Evi-1 interferes with the interaction between JNK and its substrate

Extracellular stimuli activate a class of JNK kinases, which in turn phosphorylate and activate JNK. To examine whether Evi-1 interrupts these activation processes, we evaluated phosphorylation of JNK1 in the presence of Evi-1 using the phospho-specific JNK antibody. As shown in Figure 3A, JNK1 was phosphorylated effectively by UV stimulation. This phosphorylation was not eliminated by the presence of Evi-1. We next examined the binding of JNK1 to c-Jun immobilized on glutathione–Sepharose in either the absence or presence of Evi-1 by a pull-down assay. It was observed that JNK1 from either unstimulated or UV-stimulated cells bound equally to GST–c-Jun (Figure 3B). This binding was reduced significantly by concomitant expression of Evi-1. These results point to a mechanism for JNK inhibition in which Evi-1 interrupts the interaction between JNK and its substrates. To preclude the possibility that Evi-1 may act as a substrate for JNK1 and thus compete with other substrates, we analyzed phosphorylation of endogenous Evi-1 in either untreated or UV-treated HEC1B cells using metabolic labeling with [32P]phosphate. UV exposure of HEC1B cells did not induce phosphorylation of Evi-1 even when JNK1 was overexpressed (data not shown), suggesting that Evi-1 is an authentic inhibitor of JNK rather than a tightly bound substrate.

Fig. 3. (A) Phosphorylation of JNK1 is not inhibited by Evi-1. pSRα-HA-JNK1 was transfected into COS7 cells either alone or together with pME18S-Evi-1, and the cells were treated with 60 J/m2 UV. Whole-cell extracts were subjected to SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted with the phospho-specific JNK antibody (top). Expression of HA-JNK1 and Evi-1 was monitored (middle and bottom). (B) Effect of Evi-1 on the interaction between JNK1 and c-Jun. HA-JNK was expressed in COS7 cells with or without Evi-1. The cells were either left untreated or stimulated with 60 J/m2 UV. Whole-cell extracts were incubated with GST or GST–c-Jun(1–79), and bound JNK1 was detected by immunoblotting with 12CA5 (top). Expression of HA-JNK1, Evi-1 and GST proteins was monitored as indicated.

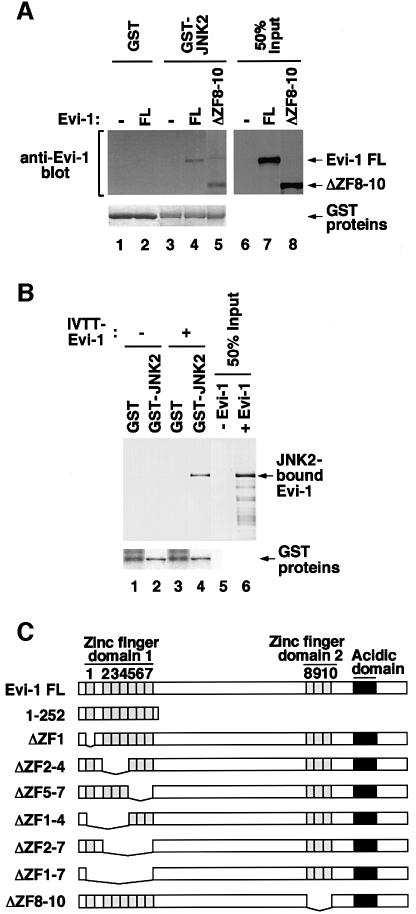

Evi-1 interacts with JNK through the first zinc finger domain

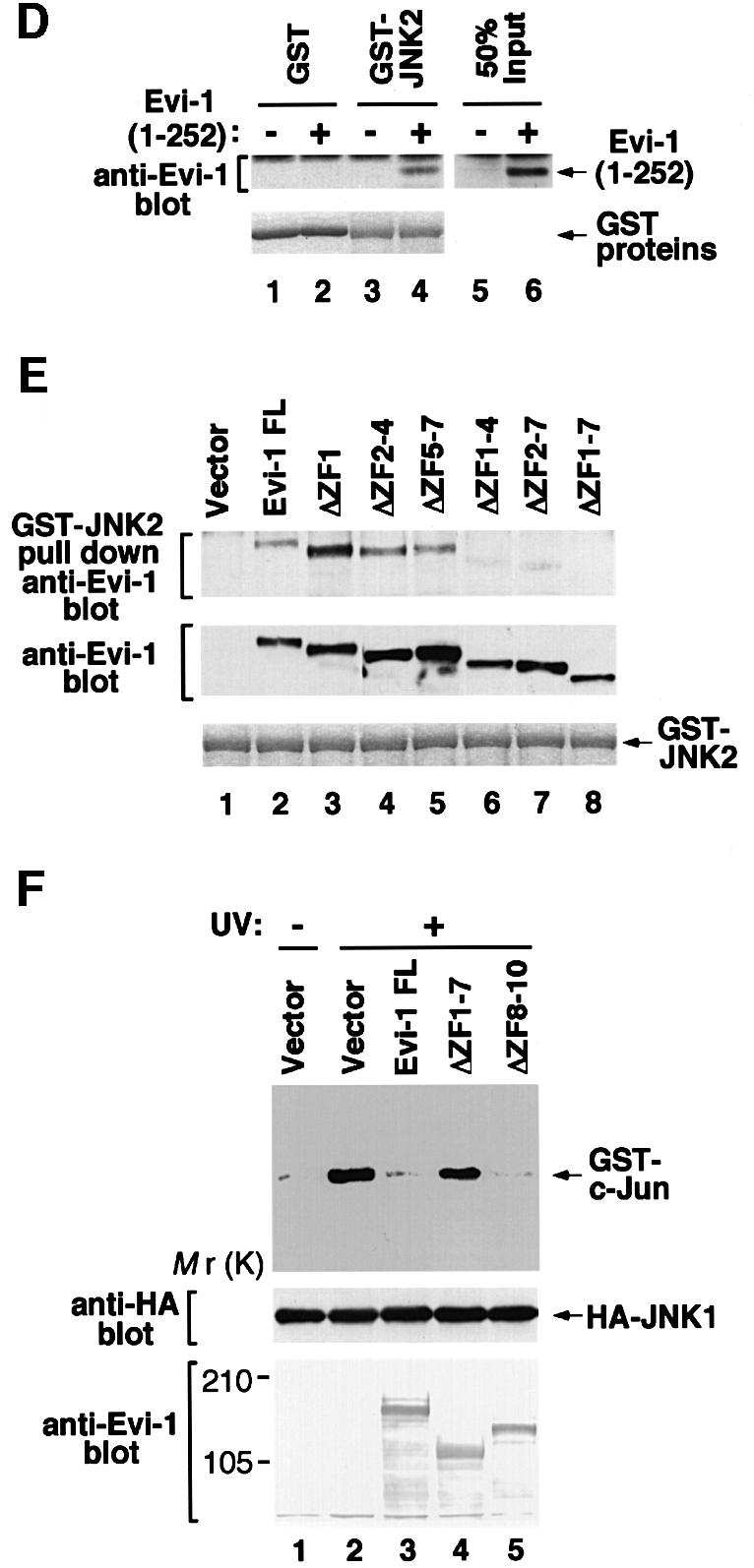

To explore the mechanism by which Evi-1 affects JNK activity, we examined whether Evi-1 physically interacts with JNK, using a pull-down assay. As shown in Figure 4A, bacterially produced GST–JNK2 immobilized on glutathione–Sepharose associated with Evi-1 that was expressed in COS7 cells. We found that GST–JNK2 also bound to Evi-1ΔZF8–10, a mutant that lacks the second zinc finger domain (ZF8–10) (Figure 4A). Although ZF8–10 is known to be responsible for the ability of Evi-1 to induce intracellular AP-1 activity (Tanaka et al., 1994), these results indicate that ZF8–10 is dispensable for the interaction between Evi-1 and JNK. These interactions are thought to be direct, as demonstrated by the pull-down assay using GST–JNK2 protein and in vitro translated Evi-1 (Figure 4B). We found that Evi-1(1–252), a C-terminally truncated mutant that consists mainly of the first zinc finger domain (ZF1–7) (Figure 4C), can associate with GST–JNK2 (Figure 4D). As shown in Figure 4E, a pull-down assay using Evi-1 mutants that harbor specific deletions within this domain revealed that Evi-1ΔZF1–7, a mutant lacking the entire ZF1–7 region, failed to interact with GST–JNK2. These results indicate that ZF1–7 is responsible for Evi-1–JNK binding.

Fig. 4. (A) Binding of full-length Evi-1 (FL) and Evi-1ΔZF8–10 to GST–JNK2 (top, lanes 4 and 5). Inputs of whole-cell extracts from COS7 cells transfected with the indicated Evi-1 constructs are shown (lanes 7 and 8). GST fusion proteins are shown in the bottom panel. (B) Binding of [35S]methionine-labeled Evi-1 that was synthesized in vitro (IVTT-Evi-1) to GST–JNK2 (top, lane 4). Input of IVTT-Evi-1 is indicated (lane 6). GST fusion proteins are shown in the bottom panel. (C) Structures of full-length Evi-1 and of its deletion mutants. Zinc finger motifs are numbered 1–10. (D) The pull-down assay for binding of Evi-1(1–252) to GST–JNK2 (top, lane 4). Input of whole-cell extracts from COS7 cells transfected with Evi-1(1–252) is shown (lane 6). GST fusion proteins are shown in the bottom panel. (E) The pull-down assay for binding of the Evi-1 mutants to GST–JNK2 (top). Expression of each Evi-1 mutant in COS7 cells was monitored (middle) and GST fusion proteins are shown (bottom). (F) The first zinc finger of Evi-1 is required for inhibition of JNK1 activity. pSRα-HA-JNK1 was transfected into COS7 cells either alone or with the Evi-1 FL, Evi-1ΔZF1–7 or Evi-1ΔZF8–10. The cells were either left untreated or treated with 60 J/m2 UV, and HA-JNK1 was immunoprecipitated with 12CA5, followed by the kinase assay (top). Expression of HA-JNK1 and the Evi-1 mutants is shown.

To determine the functional consequences of the Evi-1–JNK interaction, we examined the effect of Evi-1 mutants on JNK activity. As shown in Figure 4F, Evi-1ΔZF1–7, which cannot bind to JNK, failed to suppress UV-activated JNK1, while Evi-1ΔZF8–10, which can bind to JNK, inhibited JNK1 as effectively as full-length Evi-1. These results indicate that inhibition of JNK activity is dependent on the interaction with Evi-1 through ZF1–7.

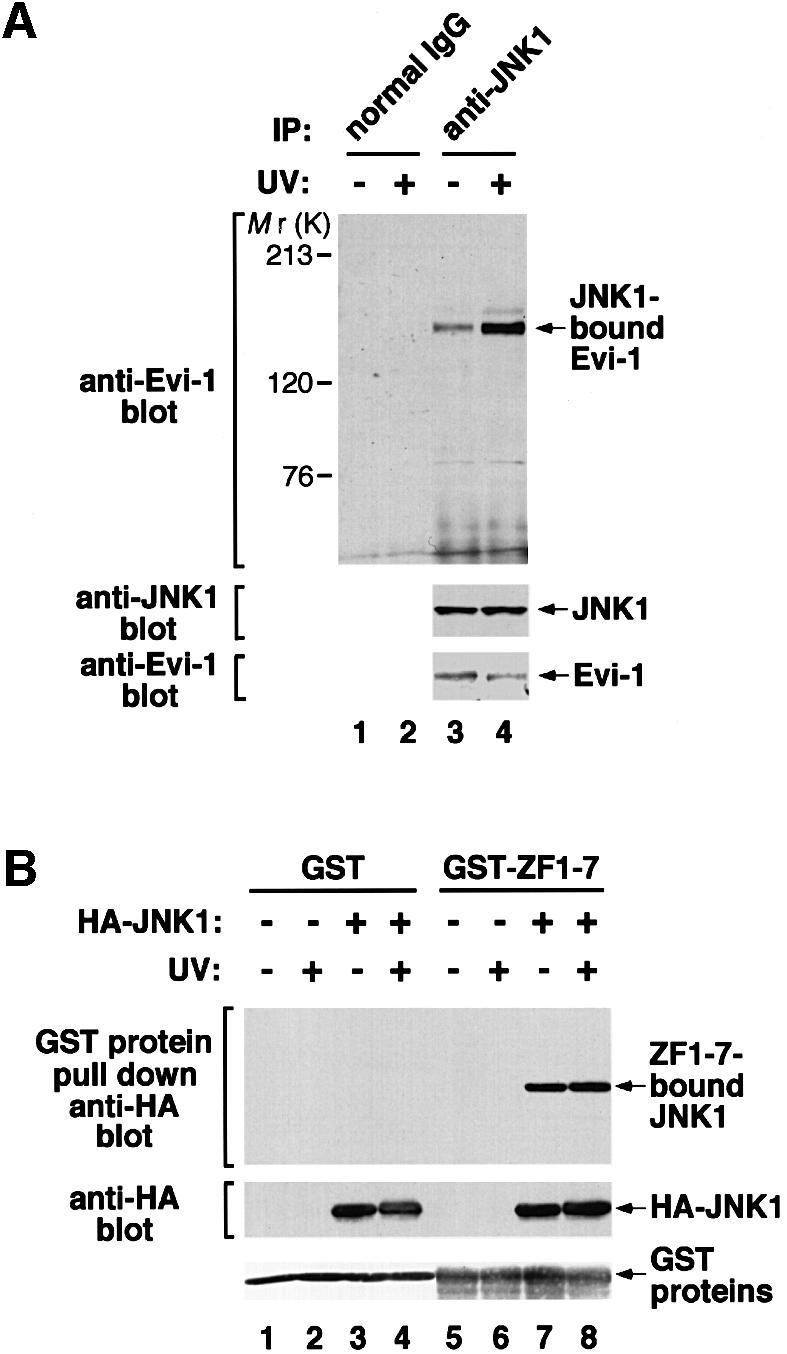

To test the in vivo interaction between JNK and Evi-1, we performed a co-precipitation assay using HEC1B cells. As shown in Figure 5A, Evi-1 was co-precipitated with JNK1, both of which were endogenously expressed in HEC1B cells. We also observed that the amount of Evi-1 co-precipitated with JNK1 was elevated in response to UV stimulation. To clarify the effect of JNK1 phosphorylation on Evi-1–JNK1 binding, the purified form of ZF1–7 (GST–ZF1–7) was incubated with HA-JNK1-containing COS7 cell extracts in vitro, and subsequently ZF1–7-bound JNK1 was detected by a pull-down assay. In contrast to the results of the co-precipitation assay, GST–ZF1–7 bound equally to JNK1 derived from either unstimulated or UV-stimulated cells (Figure 5B). Using immunofluorescent labeling of HEC1B cells, we observed that Evi-1 was consistently nuclear regardless of UV stimulation (data not shown). In contrast, JNK1, which was predominantly cytoplasmic without UV stimulation, almost translocated completely into the nucleus upon UV stimulation and co-localized with Evi-1 in the nucleus. We found a small fraction of JNK1 in the nucleus even in the absence of UV stimulation, however, which may contribute to constitutive binding of Evi-1 and JNK1 detected in unstimulated cells (Figure 5A). Available evidence suggests that the interaction of Evi-1 and JNK is reinforced upon UV stimulation as a result of UV-induced translocation of JNK into the nucleus, where the two proteins can co-localize.

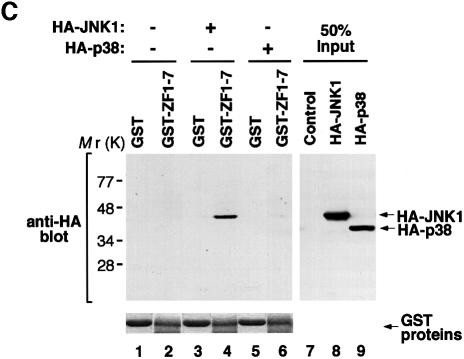

Fig. 5. (A) The constitutive interaction between Evi-1 and JNK1, and further stimulation by UV exposure. HEC1B cells were either left untreated or treated with 100 J/m2 UV. Whole-cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-JNK1, and bound Evi-1 was detected by immunoblotting with anti-Evi-1 (top). Expression of JNK1 and Evi-1 is monitored as indicated. (B) Evi-1 binds to both inactive and activated JNK. COS7 cells were transfected with HA-JNK1 and then either left untreated or treated with 60 J/m2 UV. Whole-cell extracts were incubated with GST or GST–ZF1–7, and bound JNK1 was detected by immunoblotting with 12CA5. HA-JNK1 and GST proteins were monitored as indicated. (C) JNK1, but not p38, binds to the first zinc finger domain of Evi-1. Whole-cell extracts from COS7 cells introduced with HA-JNK1 or HA-p38 were subjected to a pull-down assay using GST or GST–Evi-1(1–252) as indicated (top). Input of whole-cell extracts from HA-JNK1- or HA-p38-expressing COS7 cells is shown (lanes 8 and 9). GST fusion proteins are shown at the bottom.

To confirm the specificity of the binding of Evi-1 to JNK, we tested whether Evi-1 can interact with p38 by a pull-down assay. As shown in Figure 5C, no interaction was detected between GST–ZF1–7 and p38, whereas the GST–ZF1–7–JNK1 binding was clearly recognized. These results are consistent with the fact that Evi-1 effectively inhibits the activity of JNK1, but not that of p38.

Evi-1 protects cells from stress-induced cell death with dependence on its ability to inhibit JNK

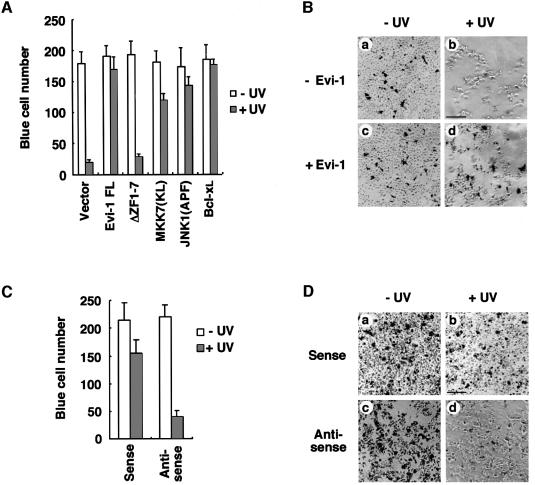

The JNK signaling pathway is implicated in apoptotic cell death induced by UV (Chen et al., 1996b), Fas ligand (FasL) (Gulbins et al., 1995) and TNF-α (Kolesnick and Golde, 1994). To test the effect of Evi-1 on these apoptotic responses, we performed transient transfection cell protection assays using 293 cells. The 293 cells were co-transfected with the β-galactosidase expression plasmid plus the effector plasmid for Evi-1, Evi-1ΔZF1–7, or various controls as indicated in Figure 6A. Each transfection was performed in duplicate for treatments with or without UV exposure and then assayed for β-galactosidase activity. A decrease in the number of β-galactosidase-expressing cells in comparison with the control group was used as an indicator of cell death (Chen et al., 1996b; Liu et al., 1996). JNK1(APF), a dominant-negative form of JNK1 (Derijard et al., 1994), blocked UV-induced cell death (Figure 6A), in agreement with the previous report (Chen et al., 1996b). A kinase-dead form of MKK7 [MKK7(KL)] (Moriguchi et al., 1997) and Bcl-xL, a strong anti-apoptotic protein (Boise et al., 1993), also suppressed cell death effectively. Under these conditions, Evi-1 blocked cell death significantly after UV exposure (Figure 6A and B). In contrast, the Evi-1ΔZF1–7 mutant that can neither interact with nor inhibit JNK did not show any effect on cell survival. We performed similar assays using HEC1B cells and found that suppression of Evi-1 expression by treatment with the antisense oligonucleotide significantly enhanced UV-induced cell death (Figure 6C and D). These results suggest that Evi-1 prevents UV-mediated apoptosis by inhibiting JNK.

Fig. 6. Blocking of UV-induced cell death by Evi-1. (A) The 293 cells were transfected in duplicate with pSRα-βgal and the indicated plasmids. Then the cells were either left untreated or treated with 60 J/m2 UV, and stained for β-galactosidase expression. The number of blue cells in five randomly chosen fields was determined, and the data shown are averages of three separate experiments. (B) Colorimetric staining of vector (pME18S)- (a and b) or pME18S-Evi-1- (c and d) transfected cells either left untreated (a and c) or treated with UV (b and d). Scale bar = 150 µm. (C) HEC1B cells were treated with 5 µg of the sense or antisense oligonucleotide for Evi-1. Then the cells were either left untreated or treated with 100 J/m2 UV, and stained for β-galactosidase expression. The number of blue cells in five randomly chosen fields was determined, and the data shown are averages of three separate experiments. (D) Colorimetric staining of the sense (a and b) or antisense (c and d) oligonucleotide-transfected cells either left untreated (a and c) or treated with UV (b and d). Scale bar = 150 µm.

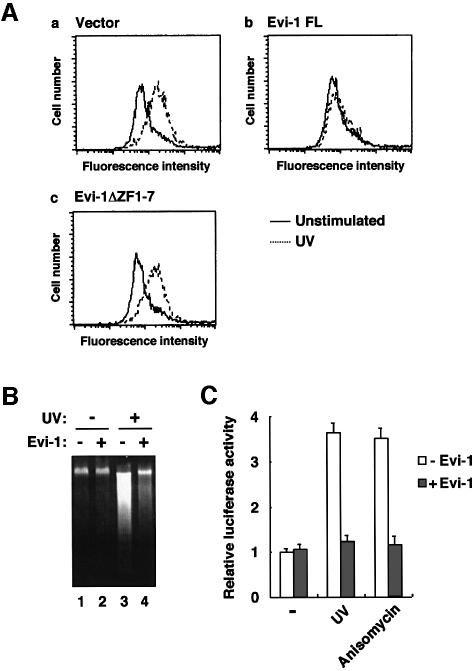

A recent study has revealed that stress activation of JNK promotes up-regulation of FasL expression in T lymphocytes, which is one of the mechanisms that potentially cause apoptosis (Faris et al., 1998). To examine whether Evi-1 affects JNK-induced up-regulation of FasL, Jurkat cells stably expressing full-length Evi-1 or Evi-1ΔZF1–7 were exposed to UV and subsequently analyzed for FasL expression as determined by flow cytometry. We observed a significant increase in the FasL expression level in response to UV stimulation in the mock-transfected cells (Figure 7A). In contrast, the Evi-1-expressing cells failed to show distinct FasL induction. Remarkably, Evi-1ΔZF1–7 has lost the ability to prevent FasL up-regulation. These results indicate that Evi-1 represses UV-induced FasL up-regulation in T lymphocytes with dependence on its ability to inhibit JNK. The DNA fragmentation assay showed that the UV-induced cell death was inhibited effectively in the Evi-1-expressing Jurkat cells (Figure 7B), in parallel with FasL expression. To confirm further the effect of Evi-1 on FasL gene expression, we performed the transcriptional response assay using a FasL promoter reporter plasmid (CD95L-486) (Faris et al., 1998). Transient transfection of CD95L-486 into Jurkat cells shows 3- to 4-fold activation by stimulation with UV or anisomycin (Figure 7C). When Evi-1 is introduced, activation of CD95L-486 is suppressed almost back to the control level. These results again suggest that Evi-1 can block stress-mediated FasL gene induction.

Fig. 7. (A) FasL expression induced by UV stimulation. Jurkat cells introduced with the empty vector (pcDNA3) (a) or the indicated form of Evi-1 (b and c) were either left untreated or treated with 100 J/m2 UV for 14 h. The cells were stained with anti-FasL and subjected to FACS analysis. (B) Blocking of UV-induced apoptosis by Evi-1 in Jurkat cells. The mock- (lanes 1 and 3) or the Evi-1-transfected Jurkat cells (lanes 2 and 4) were left untreated or treated with 100 J/m2 UV as indicated. Cellular DNA was extracted and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. (C) Inhibition of the stress-induced activation of the FasL promoter by Evi-1. CD95L-486 was transiently transfected into Jurkat cells either alone or together with pME18S-Evi-1. After 24 h, the cells were left unstimulated, or treated with either 100 J/m2 UV or 1 µg/ml anisomycin. The cells were lysed 8 h later and analyzed for luciferase activity. Values of the relative luciferase activity and error bars represent the means and standard deviations, respectively, for four separate experiments.

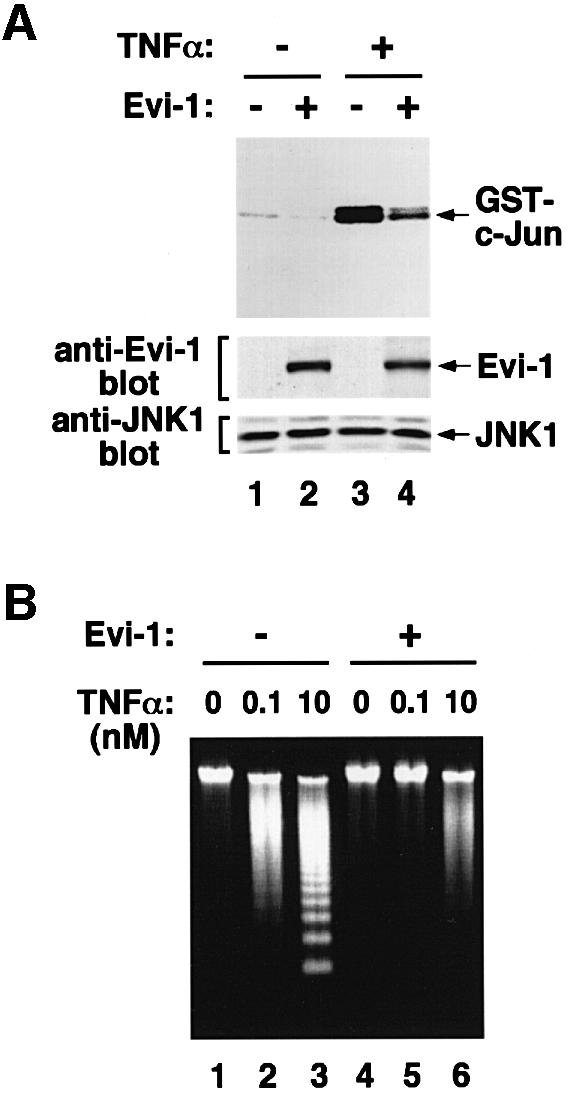

It is known that the JNK pathway is required for initiating TNF-α-induced apoptosis in U937 human monoblastic leukemia cells (Verheij et al., 1996). To examine whether Evi-1 can block cellular death induced by stress stimuli other than UV, we introduced Evi-1 into U937 cells, and assessed TNF-α-induced apoptosis. The in vitro kinase assay revealed that induced expression of Evi-1 in U937 cells effectively inhibited the TNF-α-induced JNK1 activation (Figure 8A). The DNA fragmentation assay showed that TNF-α induced apoptosis of the mock-transfected U937 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 8B). In contrast, TNF-α-mediated DNA fragmentation was inhibited markedly in the Evi-1-expressing U937 cells. These results suggest that Evi-1 can widely protect cells from stress-induced cell death in which the JNK pathway is required.

Fig. 8. (A) Evi-1 inhibits JNK in U937 cells. pcDNA3-Evi-1 was introduced into U937 cells and cells were selected for G418 resistance. The mock- and the Evi-1-transfected cells were either left untreated or treated with 10 nM TNF-α for 1 h as indicated. Then endogenous JNK1 was immunoprecipitated with anti-JNK1, and the kinase assay was performed (top). Expression of endogenous JNK1 along with Evi-1 was monitored as indicated (middle and bottom). (B) Blocking of TNF-α-induced apoptosis by Evi-1 in U937 cells. The mock- (lanes 1–3) and the Evi-1-transfected U937 cells (lanes 4–6) were treated with the indicated doses of TNF-α for 24 h. Cellular DNA was extracted and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

The ERK, but not the JNK cascade is required for AP-1-dependent transcription induced by Evi-1

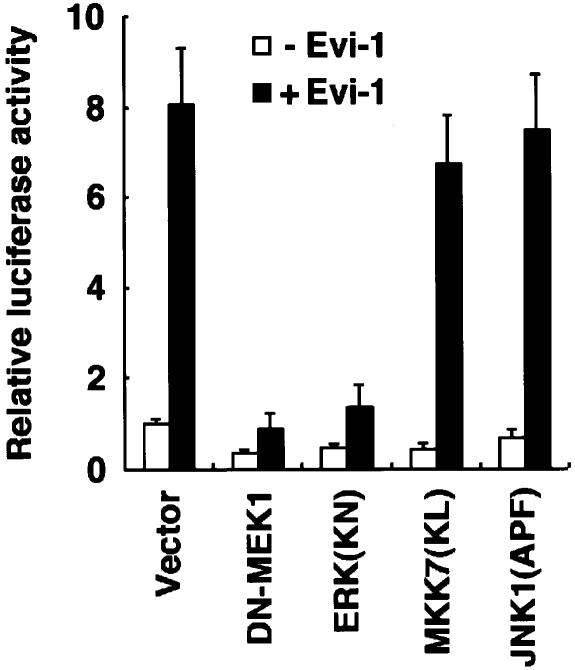

We previously demonstrated that Evi-1 increases intracellular AP-1 activity through ZF8–10 (Tanaka et al., 1994). The JNK pathway also elevates AP-1 activity through phosphorylation and activation of c-Jun. To determine the relative contribution of the JNK pathway to the ability of Evi-1 to up-regulate AP-1, we examined the effects of dominant-negative forms of the ERK or the JNK cascade constituents on Evi-1-mediated AP-1 induction. The AP-1-dependent reporter plasmid, p(TRE)×3-tk-Luc, was co-transfected into NIH 3T3 cells with each effector plasmid in the absence or presence of Evi-1 as indicated in Figure 9. As we reported elsewhere (Tanaka et al., 1994), expression of Evi-1 significantly activated p(TRE)×3-tk-Luc. This transactivation was not affected by concomitant expression of MKK7(KL) or JNK1(APF), indicating that the JNK pathway is dispensable for AP-1 induction by Evi-1. In contrast, blocking of the ERK pathway by a dominant-negative form of MEK1 (DN-MEK1) or a catalytically inactive form of ERK [ERK(KN)] (Tanaka et al., 1996) markedly suppressed the Evi-1-induced AP-1 activity. These results suggest that the ERK pathway is required for efficient AP-1 induction by Evi-1.

Fig. 9. The ERK, but not the JNK cascade is involved in AP-1-dependent transcription induced by Evi-1. The indicated expression plasmids were transfected into NIH 3T3 cells either with or without pME-18S-Evi-1. p(TRE)×3-tk-Luc was co-transfected with each set of expression plasmids, and the cells were analyzed for luciferase activity. Values of the relative luciferase activity and error bars represent the means and standard deviations, respectively, for four separate experiments.

Discussion

In this report, we have shown that Evi-1 functions as an inhibitor of JNK signaling. We have demonstrated that Evi-1 associates with JNK through the first zinc finger domain and that this association is required for efficient inhibition of JNK. Our results highlight a novel function of Evi-1, which is to inhibit JNK selectively among MAP kinases. Among the factors involved in regulating JNK activity are a cell cycle inhibitor p21 (Shim et al., 1996), GSTp (Adler et al., 1999) and HSP72 (Meriin et al., 1999). p21 appears to inhibit JNK by direct interaction, which suggests its potential role in the regulation of cellular responses induced by DNA damage. GSTp inhibits JNK activity by binding to the c-Jun–JNK complex in non-stressed conditions, while HSP72 is suggested to block repression of JNK inactivation, thus suppressing apoptosis. Although several oncoproteins are also known to prevent apoptosis induced by cellular stresses, little is known about their implication in JNK signaling. We have demonstrated that Evi-1 protects a variety of cells from stress-induced cell death that is dependent on JNK activation. Suppression of JNK activity may, by protecting cells against apoptotic signals, contribute to the oncogenic potential of Evi-1. In this respect, it is interesting to see JNK activity in cases of leukemia with elevated Evi-1 expression, which is under investigation at present. Intriguingly, Evi-1 inhibits neither p38 nor ERK. Each group of MAP kinases may play different roles in signal transduction for a variety of cellular processes. The ability of Evi-1 to inhibit JNK selectively will provide a valuable clue to understanding the function of each MAP kinase subfamily.

During ontogeny in mice, expression of Evi-1 is observed in mesoderm and neural crest-derived cells (Hoyt et al., 1997). Regions that exhibit high-level expression of Evi-1 also include the developing limbs and the surrounding areas of various cavities and ducts, such as the urinary system, the Müllerian ducts, bronchial epithelium of the lung, focal areas near the nasal cavities, the endocardial cushions and truncus swellings of the heart, strongly suggesting the anti-apoptotic function of Evi-1 (Perkins et al., 1991). The temporally and spatially restricted pattern of Evi-1 expression in embryonic tissues indicates that Evi-1 could play a physiologically important role in organogenesis and morphogenesis during embryonic development. Consistent with this idea, Evi-1 homozygous mutant mice die at E10.5 and are distinguished by widespread hypocellularity and disruption in the development of the heart, somites and neural crest-derived cells (Hoyt et al., 1997). It was reported recently that JNK1/JNK2 double mutant fetuses die on around E11.5 and display an open neural tube with reduction of cell death in the hindbrain, which points to pro-apoptotic functions for JNK (Kuan et al., 1999; Sabapathy et al., 1999). These data suggest distinct roles for Evi-1 and JNK in general cell proliferation and cell-specific developmental signaling in embryonic development. In contrast to a definitive role for Evi-1 in early development, Evi-1 expression in normal adult tissues is very low except in kidney and ovary (Perkins et al., 1991). These facts suggest that the activity of Evi-1 could be silent in normal adult tissues under physiological conditions. Given that many lines of evidence suggest a critical role for expression of Evi-1 in oncogenesis (Morishita et al., 1992b; Kreider et al., 1993; Kurokawa et al., 1995), it is important to elucidate how ectopically expressed Evi-1 leads to oncogenic change of diverse tissues, in order to understand the significance of Evi-1 function in the adult. In this regard, identification of the ability of Evi-1 to inhibit JNK activity and cellular death would reveal a role for Evi-1 in adult tissues.

It has been documented that activation of the JNK cascade is able to induce AP-1-dependent transcription (Moriguchi et al., 1997). Nonetheless, dominant-negative forms of the JNK cascade constituents failed to repress Evi-1-induced AP-1-dependent transcription in our study. This indicates that elimination of the JNK-inhibitory activity of Evi-1 does not enhance the effect of Evi-1 in increasing AP-1-dependent transcription. On the other hand, we revealed that Evi-1ΔZF8–10, which has lost the ability to enhance AP-1, remains as potent as full-length Evi-1 in JNK inhibition. This in turn indicates that disruption of the ability to induce AP-1 activity does not reinforce JNK’s inhibition by Evi-1. All these findings suggest that the JNK pathway does not make a major contribution to Evi-1-induced AP-1 activity. Significant in this regard is the recent demonstration that ERK but not JNK activation is responsible for induction of c-jun expression, at least in some cellular milieux (Leppä et al., 1998; Fritz and Kaina, 1999). Along these lines, we showed that inhibition of the ERK pathway resulted in a significant decrease in the Evi-1-induced AP-1 activity in NIH 3T3 cells (Figure 9). We had also observed that selective activation of the ERK cascade dramatically enhances AP-1-dependent transcription induced by Evi-1 (our unpublished data). These results suggest functional cooperation between Evi-1 and the ERK pathway, one of the mechanisms for which may be dependent on Evi-1-induced c-fos expression. Further studies to elucidate the precise mechanism are in progress.

Materials and methods

Construction of expression vectors

Human Evi-1 cDNA was inserted into plasmids pME18S (Tanaka et al., 1994) or pcDNA3 (Invitrogen). Construction of the retroviral vector that expresses Evi-1 was described previously (Kurokawa et al., 1995). For Flag-tagged Evi-1, the corresponding fragment was generated by PCR. C-terminally truncated versions of Evi-1 were made by digesting full-length Evi-1 with the appropriate enzymes. Construction of Evi-1ΔZF1, ΔZF2–4, ΔZF5–7 and ΔZF8–10 was described elsewhere (Tanaka et al., 1994). The other mutants of the first zinc finger domain were generated from Evi-1ΔZF1, Evi-1ΔZF2–7 and ΔZF5–7. All these Evi-1 mutants were placed in pME18S or pcDNA3. GST–ZF1–7 was made by inserting the corresponding fragments into pGEX-2TK (Pharmacia). The HA-tagged human JNK1 cDNA was inserted into pSRα and JNK1(APF) was inserted into pcDNA3 (Derijard et al., 1994). pCMVMK, which is an expression vector for a rat ERK1–ERK2 chimeric protein, was described elsewhere (Ueki et al., 1994). HA-tagged human p38 and MKK7(KL) were placed in pcDL-SRα456 (Moriguchi et al., 1996). ERK(KN) and DN-MEK1 were made as described elsewhere (Tanaka et al., 1996) and inserted into pRc/CMV and pactEF, respectively. Bcl-xL was inserted into the pUC-CAAGS vector. For GST–JNK2, the rat JNK2 cDNA was inserted into pGEX-2T. GST–c-Jun(1–79) was made by inserting the corresponding fragment generated by PCR into pGEX-2T.

Cell lines, transfections and oligonucleotide treatments

COS7, Rat-1, HEC1B and NIH 3T3 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). MOLM-1, Jurkat and U937 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 with 10% FCS. Production of the retrovirus stock that expresses Evi-1, and retroviral infection into Rat-1 and NIH 3T3 cells were performed as described previously (Kurokawa et al., 1995). Transient transfection into COS7 cells was carried out by the DEAE–dextran method as described elsewhere (Kurokawa et al., 1995). Transfection of pcDNA3-Evi-1 or -Evi-1ΔZF1–7 into Jurkat or U937 cells was performed by electroporation (Faris et al., 1998), and the cells were selected for neomycin-resistant gene expression with G418 (Gibco-BRL). Phosphothioate oligonucleotides were transfected into HEC1B and MOLM-1 cells by using SuperFect Transfection Reagents (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. The oligonucleotide sequences were as follows: sense, TATCGCTGCGAAGACTGTGA; antisense, TCACAGTCTTCGCAGCGATA.

Western blot analyses, protein kinase assays and pull-down assays

The cells indicated were lysed in the lysis buffer described elsewhere (Moriguchi et al., 1996). Whole-cell extracts were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-HA (12CA5; Boehringer Mannheim), anti-Evi-1 (Tanaka et al., 1994), anti-ERK (αC92) (Tobe et al., 1991), anti-JNK1 (PharMingen), phospho-c-Jun (NEB), anti-c-Jun (KM-1; Santa Cruz) or the phospho-specific JNK antibody (pJNK; Santa Cruz). To assess kinase activities, JNK1, p38 or ERK was immunoprecipitated with 12CA5, anti-JNK1 or αC92, and subjected to kinase assays as described elsewhere (Moriguchi et al., 1996). Recombinant GST–c-Jun and ATF2 were expressed in the bacterial strain BL21 and purified using glutathione–Sepharose beads (Pharmacia). MBP was purchased from Sigma. For pull-down assays, 5 µg of GST fusion proteins were collected on glutathione–Sepharose beads (Pharmacia), incubated for 3 h at 4°C with 250 µg of cell extracts or [35S]methionine-labeled proteins that were synthesized using TNT Coupled Reticulocyte Lysate Systems (Promega), and analyzed by SDS–PAGE. Fractions of the reaction mixture were analyzed by Coomassie staining to visualize GST fusion proteins.

Cell protection assays and FasL expression

The 293 or HEC1B cells were transfected with the β-galactosidase expression vector (pSSRα-βgal) (Tanaka et al., 1994) together with the indicated plasmids using SuperFect Transfection Reagents. The cells were stained for β-galactosidase as described elsewhere (Chen et al., 1996b). Immunostaining for FasL expression was performed by incubating the cells with the biotin-conjugated anti-FasL monoclonal antibody (NOK1; PharMingen) followed by phycoerythrin-conjugated streptavidin (PharMingen). The cells were analyzed by flow cytometry using the Cell Quest program (Beckton Dickinson).

DNA fragmentation assays and transcriptional response assays

DNA fragmentation assays and transcriptional response assays were performed as described elsewhere (Tanaka et al., 1994; Chen et al., 1996a; Faris et al., 1998). As an internal control of transfection efficiency, pSSRα-βgal was co-transfected. Relative luciferase activities were measured in cell extracts using the luciferase assay system (Promega) and a luminometer (Lumat, Berthold), and normalized to the β-galactosidase activity.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors thank R.J.Davis for JNK1 and JNK1(APF) cDNAs, T.Kadowaki for pCMVMK, DN-MEK1, ERK(KN) and the αC92 antibody, Y.Tsujimoto for Bcl-xL, and G.A.Koretzky for CD95L-486. This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Cancer Research from the Ministry of Health and Welfare and from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture of Japan, and by The Ryoichi Naito Foundation for Medical Research.

References

- Adler V. et al. (1999) Regulation of JNK signaling by GSTp. EMBO J., 18, 1321–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew C., Kilbey,A., Clark,A.M. and Walker,M. (1997) The Evi-1 proto-oncogene encodes a transcriptional repressor activity associated with transformation. Oncogene, 14, 569–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boise L.H., Gonzalez,G.M., Postema,C.E., Ding,L., Lindsten,T., Turka,L.A., Mao,X., Nunez,G. and Thompson,C.B. (1993) bcl-x, a bcl-2-related gene that functions as a dominant regulator of apoptotic cell death. Cell, 74, 597–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.R., Meyer,C.F. and Tan,T.H. (1996a) Persistent activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 (JNK1) in γ radiation-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 631–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.R., Wang,X., Templeton,D., Davis,R.J. and Tan,T.H. (1996b) The role of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) in apoptosis induced by ultraviolet C and γ radiation. Duration of JNK activation may determine cell death and proliferation. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 31929–31936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis R.J. (1993) The mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathway. J. Biol. Chem., 268, 14553–14556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derijard B., Hibi,M., Wu,I.H., Barrett,T., Su,B., Deng,T., Karin,M. and Davis,R.J. (1994) JNK1: a protein kinase stimulated by UV light and Ha-Ras that binds and phosphorylates the c-Jun activation domain. Cell, 76, 1025–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derijard B., Raingeaud,J., Barrett,T., Wu,I.H., Han,J., Ulevitch,R.J. and Davis,R.J. (1995) Independent human MAP-kinase signal transduction pathways defined by MEK and MKK isoforms. Science, 267, 682–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanger G.R., Gerwins,P., Widmann,C., Jarpe,M.B. and Johnson,G.L. (1997) MEKKs, GCKs, MLKs, PAKs, TAKs and tpls: upstream regulators of the c-Jun amino-terminal kinases? Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 7, 67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faris M., Kokot,N., Latinis,K., Kasibhatla,S., Green,D.R., Koretzky,G.A. and Nel,A. (1998) The c-Jun N-terminal kinase cascade plays a role in stress-induced apoptosis in Jurkat cells by up-regulating Fas ligand expression. J. Immunol., 160, 134–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz G. and Kaina,B. (1999) Activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 by UV irradiation is inhibited by wortmannin without affecting c-jun expression. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 1768–1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulbins E. et al. (1995) FAS-induced apoptosis is mediated via a ceramide-initiated RAS signaling pathway. Immunity, 2, 341–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J., Lee,J.D., Bibbs,L. and Ulevitch,R.J. (1994) A MAP kinase targeted by endotoxin and hyperosmolarity in mammalian cells. Science, 265, 808–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland P.M., Suzanne,M., Campbell,J.S., Noselli,S. and Cooper,J.A. (1997) MKK7 is a stress-activated mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase functionally related to hemipterous. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 24994–24998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt P.R., Bartholomew,C., Davis,A.J., Yutzey,K., Gamer,L.W., Potter,S.S., Ihle,J.N. and Mucenski,M.L. (1997) The Evi1 proto-oncogene is required at midgestation for neural, heart and paraxial mesenchyme development. Mech. Dev., 65, 55–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharbanda S., Ren,R., Pandey,P., Shafman,T.D., Feller,S.M., Weichselbaum,R.R. and Kufe,D.W. (1995) Activation of the c-Abl tyrosine kinase in the stress response to DNA-damaging agents. Nature, 376, 785–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolesnick R. and Golde,D.W. (1994) The sphingomyelin pathway in tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-1 signaling. Cell, 77, 325–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreider B.L., Orkin,S.H. and Ihle,J.N. (1993) Loss of erythropoietin responsiveness in erythroid progenitors due to expression of the Evi-1 myeloid-transforming gene. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 90, 6454–6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuan C.-Y., Yang,D.D., Samanta Roy,D.R., Davis,R.J., Rakic,P. and Flavell,R.A. (1999) The Jnk1 and Jnk2 protein kinases are required for regional specific apoptosis during early brain development. Neuron, 22, 667–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurokawa M., Ogawa,S., Tanaka,T., Mitani,K., Yazaki,Y., Witte,O.N. and Hirai,H. (1995) The AML1/Evi-1 fusion protein in the t(3;21) translocation exhibits transforming activity on Rat1 fibroblasts with dependence on the Evi-1 sequence. Oncogene, 11, 833–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurokawa M., Mitani,K., Imai,Y., Ogawa,S., Yazaki,Y. and Hirai,H. (1998a) The t(3;21) fusion product, AML1/Evi-1, interacts with Smad3 and blocks transforming growth factor-β-mediated growth inhibition of myeloid cells. Blood, 92, 4003–4012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurokawa M., Mitani,K., Irie,K., Matsuyama,T., Takahashi,T., Chiba,S., Yazaki,Y., Matsumoto,K. and Hirai,H. (1998b) The oncoprotein Evi-1 represses TGF-β signalling by inhibiting Smad3. Nature, 394, 92–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakis J.M., Banerjee,P., Nikolakaki,E., Dai,T., Rubie,E.A., Ahmad,M.F., Avruch,J. and Woodgett,J.R. (1994) The stress-activated protein kinase subfamily of c-Jun kinases. Nature, 369, 156–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppä S., Saffrich,R., Ansorge,W. and Bohmann,D. (1998) Differential regulation of c-Jun by ERK and JNK during PC12 cell differentiation. EMBO J., 17, 4404–4413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy E.R., Parganas,E., Morishita,K., Fichelson,S., James,L., Oscier,D., Gisselbrecht,S., Ihle,J.N. and Buckle,V.J. (1994) DNA rearrangements proximal to the EVI1 locus associated with the 3q21q26 syndrome. Blood, 83, 1348–1354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin A., Minden,A., Martinetto,H., Claret,F.X., Lange,C.C., Mercurio,F., Johnson,G.L. and Karin,M. (1995) Identification of a dual specificity kinase that activates the Jun kinases and p38-Mpk2. Science, 268, 286–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.G., Hsu,H., Goeddel,D.V. and Karin,M. (1996) Dissection of TNF receptor 1 effector functions: JNK activation is not linked to apoptosis while NF-κB activation prevents cell death. Cell, 87, 565–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopingco M.C. and Perkins,A.S. (1996) Molecular analysis of Evi1, a zinc finger oncogene involved in myeloid leukemia. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol., 211, 211–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meriin A.B., Yaglom,J.A., Gabai,V.L., Mosser,D.D., Zon,L. and Sherman,M.Y. (1999) Protein-damaging stresses activate c-Jun N-terminal kinase via inhibition of its dephosphorylation: a novel pathway controlled by HSP72. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 2547–2555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitani K., Ogawa,S., Tanaka,T., Miyoshi,H., Kurokawa,M., Mano,H., Yazaki,Y., Ohki,M. and Hirai,H. (1994) Generation of the AML1–EVI-1 fusion gene in the t(3;21)(q26;q22) causes blastic crisis in chronic myelocytic leukemia. EMBO J., 13, 504–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriguchi T. et al. (1996) A novel kinase cascade mediated by mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 6 and MKK3. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 13675–13679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriguchi T., Toyoshima,F., Masuyama,N., Hanafusa,H., Gotoh,Y. and Nishida,E. (1997) A novel SAPK/JNK kinase, MKK7, stimulated by TNFα and cellular stresses. EMBO J., 16, 7045–7053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishita K., Parker,D.S., Mucenski,M.L., Jenkins,N.A., Copeland,N.G. and Ihle,J.N. (1988) Retroviral activation of a novel gene encoding a zinc finger protein in IL-3-dependent myeloid leukemia cell lines. Cell, 54, 831–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishita K., Parganas,E., Douglass,E.C. and Ihle,J.N. (1990) Unique expression of the human Evi-1 gene in an endometrial carcinoma cell line: sequence of cDNAs and structure of alternatively spliced transcripts. Oncogene, 5, 963–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishita K., Parganas,E., Matsugi,T. and Ihle,J.N. (1992a) Expression of the Evi-1 zinc finger gene in 32Dc13 myeloid cells blocks granulocytic differentiation in response to granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Mol. Cell. Biol., 12, 183–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishita K., Parganas,E., William,C.L., Whittaker,M.H., Drabkin,H., Oval,J., Taetle,R., Valentine,M.B. and Ihle,J.N. (1992b) Activation of EVI1 gene expression in human acute myelogenous leukemias by translocations spanning 300–400 kilobases on chromosome band 3q26. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 3937–3941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucenski M.L., Taylor,B.A., Ihle,J.N., Hartley,J.W., Morse,H.C,III, Jenkins,N.A. and Copeland,N.G. (1988) Identification of a common ecotropic viral integration site, Evi-1, in the DNA of AKXD murine myeloid tumors. Mol. Cell. Biol., 8, 301–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa S. et al. (1996a) Structurally altered Evi-1 protein generated in the 3q21q26 syndrome. Oncogene, 13, 183–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa S., Kurokawa,M., Tanaka,T., Tanaka,K., Hangaishi,A., Mitani,K., Kamada,N., Yazaki,Y. and Hirai,H. (1996b) Increased Evi-1 expression is frequently observed in blastic crisis of chronic myelocytic leukemia. Leukemia, 10, 788–794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters P., Wlodarska,I., Baens,M., Criel,A., Selleslag,D., Hagemeijer,A., Van den Berghe,H. and Marynen,P. (1997) Fusion of ETV6 to MDS1/EVI1 as a result of t(3;12)(q26;p13) in myeloproliferative disorders. Cancer Res., 57, 564–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins A.S., Mercer,J.A., Jenkins,N.A. and Copeland,N.G. (1991) Patterns of Evi-1 expression in embryonic and adult tissues suggest that Evi-1 plays an important regulatory role in mouse development. Development, 111, 479–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson M.J. and Cobb,M.H. (1997) Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 9, 180–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell M., List,A., Greenberg,P., Woodward,S., Glinsmann,B., Parganas,E., Ihle,J. and Taetle,R. (1994) Expression of EVI1 in myelodysplastic syndromes and other hematologic malignancies without 3q26 translocations. Blood, 84, 1243–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabapathy K., Jochum,W., Hochedlinger,K., Chang,L., Karin,M. and Wagner,E.F. (1999) Defective neural tube morphogenesis and altered apoptosis in the absence of both JNK1 and JNK2. Mech. Dev., 89, 115–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez I., Hughes,R.T., Mayer,B.J., Yee,K., Woodgett,J.R., Avruch,J., Kyriakis,J.M. and Zon,L.I. (1994) Role of SAPK/ERK kinase-1 in the stress-activated pathway regulating transcription factor c-Jun. Nature, 372, 794–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim J., Lee,H., Park,J., Kim,H. and Choi,E.J. (1996) A non-enzymatic p21 protein inhibitor of stress-activated protein kinases. Nature, 381, 804–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T., Nishida,J., Mitani,K., Ogawa,S., Yazaki,Y. and Hirai,H. (1994) Evi-1 raises AP-1 activity and stimulates c-fos promoter transactivation with dependence on the second zinc finger domain. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 24020–24026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T., Mitani,K., Kurokawa,M., Ogawa,S., Tanaka,K., Nishida,J., Yazaki,Y., Shibata,Y. and Hirai,H. (1995) Dual functions of the AML1/Evi-1 chimeric protein in the mechanism of leukemogenesis in t(3;21) leukemias. Mol. Cell. Biol., 15, 2383–2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T. et al. (1996) The extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway phosphorylates AML1, an acute myeloid leukemia gene product and potentially regulates its transactivation ability. Mol. Cell. Biol., 16, 3967–3979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobe K. et al. (1991) Insulin and 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate activation of two immunologically distinct myelin basic protein/microtubule-associated protein 2 (MBP/MAP2) kinases via de novo phosphorylation of threonine and tyrosine residues. J. Biol. Chem., 266, 24793–24803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tournier C., Whitmarsh,A.J., Cavanagh,J., Barrett,T. and Davis,R.J. (1997) Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 7 is an activator of the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 7337–7342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treisman R. (1996) Regulation of transcription by MAP kinase cascades. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 8, 205–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueki K. et al. (1994) Feedback regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase activity of c-Raf-1 by insulin and phorbol ester stimulation. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 15756–15761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheij M. et al. (1996) Requirement for ceramide-initiated SAPK/JNK signalling in stress-induced apoptosis. Nature, 380, 75–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Z., Dickens,M., Raingeaud,J., Davis,R.J. and Greenberg,M.E. (1995) Opposing effects of ERK and JNK-p38 MAP kinases on apoptosis. Science, 270, 1326–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanke B.W., Boudreau,K., Rubie,E., Winnett,E., Tibbles,L.A., Zon,L., Kyriakis,J., Liu,F.F. and Woodgett,J.R. (1996) The stress-activated protein kinase pathway mediates cell death following injury induced by cis-platinum, UV irradiation or heat. Curr. Biol., 6, 606–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]