Abstract

osmY is a stationary phase-induced and osmotically regulated gene in Escherichia coli that requires the stationary phase RNA polymerase (EσS) for in vivo expression. We show here that the major RNA polymerase, Eσ70, also transcribes osmY in vitro and, depending on genetic background, even in vivo. The cAMP receptor protein (CRP) bound to cAMP, the leucine-responsive regulatory protein (Lrp) and the integration host factor (IHF) inhibit transcription initiation at the osmY promoter. The binding site for CRP is centred at –12.5 from the transcription start site, whereas Lrp covers the whole promoter region. The site for IHF maps in the –90 region. By mobility shift assay, permanganate reactivity and in vitro transcription experiments, we show that repression is much stronger with Eσ70 than with EσS holoenzyme. We conclude that CRP, Lrp and IHF inhibit open complex formation more efficiently with Eσ70 than with EσS. This different ability of the two holoenzymes to interact productively with promoters once assembled in complex nucleoprotein structures may be a crucial factor in generating σS selectivity in vivo.

Keywords: repressors/RNA polymerase/rpoS/σ factor/stationary phase

Introduction

Entry of Escherichia coli cells into stationary phase results in complex morphological and physiological changes (Siegele and Kolter, 1992; Hengge-Aronis et al., 1993). Stationary phase E.coli cells become more resistant to a variety of stresses including starvation, near UV radiation, high temperature, hydrogen peroxide, acidic pH and high medium osmolarity (Loewen and Hengge-Aronis, 1994). These properties result from the induction of a set of specific genes. Many of these genes are expressed under the control of the major regulator of the general stress response, σS, the product of the rpoS gene (Lange and Hengge-Aronis, 1991). σS has been shown to interact with core RNA polymerase and to transcribe several promoters, thus appearing as a ‘second principal’ σ factor in stationary phase E.coli (Mulvey and Loewen, 1989; Nguyen et al., 1993; Tanaka et al., 1993).

σS is homologous to σ70, the major σ factor, even in the domains involved in interaction with the –10 and the –35 consensus regions of a promoter (Lonetto et al., 1992). In agreement with these properties, σS and σ70 show overlapping promoter specificities in vitro (Nguyen et al., 1993; Tanaka et al., 1993; Ding et al., 1995; Kusano et al., 1996; Nguyen and Burgess, 1997; Ballesteros et al., 1998; Bordes et al., 2000). However, in contrast to the relaxed specificity observed under in vitro conditions, many promoters are known to be transcribed in vivo solely by one of the two holoenzymes. This discrepancy between the analogous recognition properties in vitro and the in vivo EσS recognition specificity has been pointed out (for reviews see Hengge-Aronis, 1999; Ishihama, 1999). In this respect, higher concentrations of potassium glutamate and lower template supercoiling have been shown to contribute to EσS selectivity of some stationary phase-specific promoters (Ding et al., 1995; Kusano et al., 1996; Nguyen and Burgess, 1997). These experimental conditions for increased EσS selective transcription in vitro seem to be in agreement with the in vivo intracellular conditions prevailing in late stationary phase or after osmotic upshift.

osmY (also called csi-5) is an example of a gene that is strongly dependent on σS in vivo (Lange et al., 1993; Yim et al., 1994) but transcribed by RNA polymerase containing either σS or σ70 in vitro (Ding et al., 1995; Kusano et al., 1996). This promoter is induced not only during transition into stationary phase but also in response to increased medium osmolarity during exponential growth (Yim and Villarejo, 1992; Hengge-Aronis et al., 1993). osmY expression is controlled at the transcriptional level from a single promoter under both conditions and the gene encodes the periplasmic protein OsmY of unknown function (Yim and Villarejo, 1992; Lange et al., 1993; Yim et al., 1994). The osmY promoter sequence possesses a –10 region (TATATT) with strong similarity to the σ70/σS consensus, but a –35 region (CCGAGC) with a poor match to the –35 consensus sequence of σ70. Genetic data indicated that this promoter is repressed by three global regulators: integration host factor (IHF), cAMP–receptor protein (CRP) and leucine-responsive regulatory protein (Lrp) (Lange et al., 1993).

In the present study, we asked whether the presence of the regulatory factors could affect preferentially one of the two holoenzymes (EσS or Eσ70) for in vitro transcription initiation, thus mimicking the σ factor selectivity observed in vivo. We report direct evidence that IHF, cAMP–CRP and Lrp mainly inhibit Eσ70-dependent expression at the osmY promoter.

Results

Inhibition by Lrp, IHF and cAMP–CRP in the control of osmY expression in vivo in the presence or absence of σS

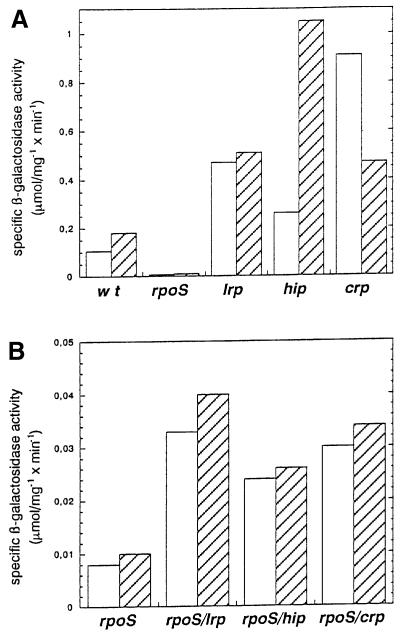

Using a single copy transcriptional lac fusion to the chromosomal copy of osmY, Lange et al. (1993) have shown that expression of the osmY promoter depends on the presence of an intact rpoS allele in all growth media and genetic backgrounds. However, the conditions that strongly increase σS levels are not always sufficient to induce the osmY promoter fully. In minimal medium, the depletion of glucose, ammonium or phosphate ions results in a clear σS induction, but only in a modest increase of the β-galactosidase activity of the osmY::lac fusion (Weichart et al., 1993). Besides σS availability, other transcription factors such as Lrp, IHF and CRP negatively regulate osmY expression. Figure 1 shows the β-galactosidase activities of cells grown in M9 medium containing 0.1% glucose until late log phase or stationary phase. A significant increase in activities can be observed in lrp, hip and crp strains in both conditions.

Fig. 1. Effect of single or double deficiencies in σS, Lrp, IHF and CRP on the expression of the osmY gene. Strain RO151, which carries the single copy osmY (csi-5)::lacZ transcriptional fusion, and its derivatives carrying a nlpD-rpoS deletion (which has the same effect on osmY expression as a mutation affecting rpoS alone), lrp::Tn10, hip::cat or a deletion in crp, were grown in minimal medium M9 supplemented with 0.1% glucose. β-galactosidase activities were determined during late exponential phase (white bars) or in stationary phase (overnight cultures; hatched bars). (A) Mutants defective in a single regulatory gene. (B) Mutants carrying lesions in rpoS in combination with a mutation in one of the other regulatory genes. Measurements were performed in triplicate and average values are given (±10%).

Lrp, a small homodimeric protein, acts as a transcriptional regulator by binding to DNA. Its activity is modulated by the presence of leucine or alanine (for a review see Newman and Lin, 1995). Lrp activates some genes involved in anabolism and represses others involved in catabolism. Lrp levels are constitutively high during growth and after entry into stationary phase in glucose minimal medium (Landgraf et al., 1996; Azam et al., 1999). The absence of Lrp derepresses expression of the osmY fusion by a 3- to 4-fold factor in late log and stationary phases. In the absence of σS, although the activities are ∼10-fold lower, a similar derepression is observed (Figure 1B).

IHF is a small heterodimeric histone-like protein that binds and bends DNA (Friedman, 1988). It is involved in a great variety of processes including replication, site-specific recombination and transcriptional regulation. The absence of a functional IHF protein leads to a 2-fold increase in osmY::lac expression in late log phase but to a 6-fold increase in stationary phase (Figure 1A). This result is consistent with the dramatic increase in the amount of IHF observed in stationary phase cell cultures, partly under the dependence on σS (Aviv et al., 1994; Azam et al., 1999). The derepression in the rpoS background is still observed but with little difference between stationary phase and late log cells (Figure 1B), consistent with the lack of IHF stationary phase induction in the rpoS mutant (Aviv et al., 1994).

The presence of a mutation in the crp gene leads to a 9-fold increase in late log phase expression of the fusion. Much of this effect is probably indirect, i.e. due to increased σS levels in the crp mutant (Lange and Hengge-Aronis, 1994). The inhibitory effect of CRP appears to be only 2-fold in the stationary phase. Since stationary phase levels of σS are similar in wild-type and in the crp backgrounds, this inhibitory effect of CRP is probably a direct effect on osmY expression. In the rpoS mutant, CRP inhibits the osmY::lac activity to the same extent in stationary phase and in late log phase (i.e. 4-fold). These data suggest that, in stationary phase, the direct inhibitory effect of CRP on osmY expression is more pronounced with Eσ70 than with EσS.

In conclusion, the in vivo data show that Lrp, IHF and CRP are able to repress osmY. The quantitative interpretation of these data, however, is complicated by the fact that the regulators involved also affect the cellular levels of each other (Aviv et al., 1994; Lange and Hengge-Aronis, 1994; Bouvier et al., 1998). This means that the regulatory effects observed may be the sum of direct and indirect effects. We therefore decided to investigate the in vitro ability of Lrp, IHF and CRP to bind to the osmY promoter, and the direct effects of these regulators on open complex formation and in vitro transcription of osmY.

In vitro analyses of the binding of EσS, Eσ70, cAMP–CRP, IHF and Lrp at the osmY promoter region

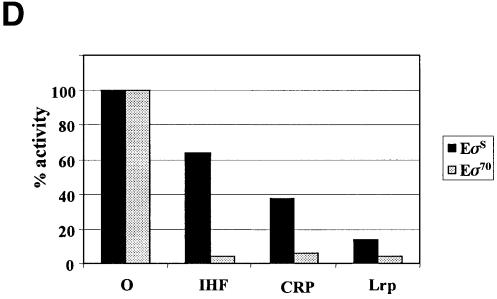

To analyse precisely binding of the two holoenzymes and the repressors in the osmY promoter region, DNase I footprinting experiments were performed using a radiolabelled PCR osmY fragment extending from positions –175 to +48 with respect to the transcriptional start site. Both RNA polymerases are clearly able to bind to the osmY promoter. They protect DNA from position –51.5 to +19.5 on the non-template strand and from –54.5 to +12.5 on the template strand (Figure 2A and B, respectively). However, significant differences in the protection patterns were observed: (i) EσS strongly protects the sequence downstream of –26.5 while protection by Eσ70 in this region is clearly weaker (Figure 2); (ii) Eσ70 strongly protects the region upstream of –35, especially on the non-template strand; and (iii) on the same strand, an EσS-specific hypersensitive site is observed at –42.5 (Figure 2A).

Fig. 2. DNase I footprint analysis of the complexes formed by EσS or Eσ70 holoenzymes (150 nM) at osmY. After DNase I attack, the heparin-resistant complexes were purified and samples were analysed on a 7% denaturing polyacrylamide gel, which was calibrated using a sequencing reaction for G + A (lane 4). Results obtained on the non-template and template strands are shown in (A) and (B), respectively: DNA alone (lane 1), EσS (lane 2) and Eσ70 (lane 3).

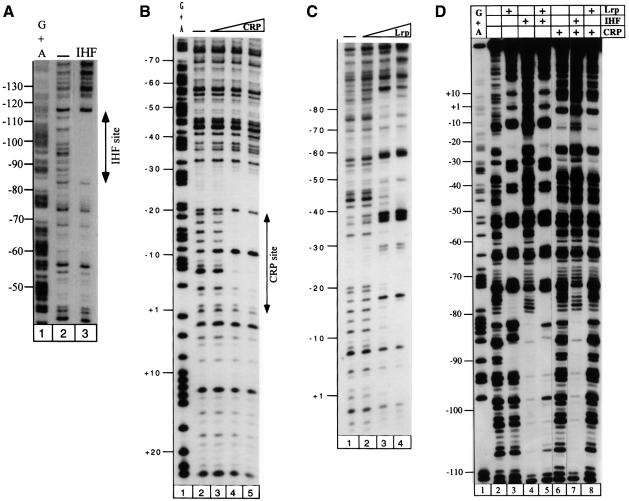

The IHF protein at 100 nM binds to the far upstream region of the promoter protecting the template strand between positions –110.5 and –82.5 from DNase I cleavage (Figure 3A). IHF recognizes a specific DNA sequence centred at position –98.5, which is only distantly related to the consensus sequence (WATCAANNNNTTR; Figure 4B; Craig and Nash, 1984; Goodrich et al., 1990; Rice et al., 1996).

Fig. 3. DNase I footprint analysis of the complexes formed at the template strand of the osmY promoter with IHF (A), CRP (B), Lrp (C) or at the non-template strand with a mixture of repressors (D). The reaction mix was treated with DNase I as described in Materials and methods. Samples were analysed on a 7% denaturing polyacrylamide gel, which was calibrated using a sequencing reaction for G + A (Maxam and Gilbert, 1977). Repressor concentration: (A) IHF (100 nM, lane 3); (B) CRP (10, 50 and 150 nM, lanes 3–5); (C) Lrp (5, 25 and 125 nM, lanes 2–4); and (D) IHF (50 nM), CRP (50 nM) and Lrp (8 nM). Note that the DNA fragment has been overdigested by DNase I in (A) lane 2 with respect to lane 3. The reactive bands upstream of the IHF-binding site are located at the same positions in lanes 2 and 3 but are overexposed in lane 3.

Fig. 4. (A) Summary of the protection patterns observed at the osmY promoter in the presence of IHF and CRP. The centre of the CRP-binding site is indicated by an asterisk, –10 and –35 regions are boxed. (B) Alignment of the osmY-binding sites with the respective consensus sites of CRP, IHF and Lrp where W = A/T, R = A/G, Y = C/T, H = ‘not G’, D = ‘not C’ (Craig and Nash, 1984; Kolb et al., 1993; Cui et al., 1996). The centres of the CRP- and Lrp-binding sites, indicated by asterisks, are numbered with respect to the transcription start site. For IHF, only the most conserved half of the binding site is indicated (Goodrich et al., 1990). Nucleotides matching the consensus sequences are underlined.

In the presence of cAMP, protection by the CRP protein is observed in the –10 region and extends from at least –19.5 to +1.5 on the template strand (Figure 3B). The sequence centred at –12.5 contains between –20 and –15, the TGTGA motif, the best conserved element of the palindromic CRP-binding site, whereas only two positions match the consensus in the symmetric element between –9 and –5 (Figure 4B; Kolb et al., 1993). Thus, its affinity is ∼4- to 5-fold lower than at lac (data not shown). The specific binding sites for IHF and CRP at osmY are indicated in Figure 4.

In contrast to CRP and IHF, Lrp does not bind to a single site, but binds co-operatively to the whole promoter region from –90 to +1 (Figure 3C). As previously reported, there is a periodic pattern of protection and enhanced cleavages separated by 10–11 bp (Wiese et al., 1997; Marschall et al., 1998). The most highly hypersensitive bands appear around positions –57.5 and –35.5 on the template strand and around –33.5 and –12.5 on the non-template strand, suggesting the existence of several Lrp-binding sites. In addition, circular permutation analysis of the mobilities of the osmY–Lrp complexes showed that Lrp bends the promoter region and forms a nucleoprotein complex at osmY. The in vitro methylation of the dam site at positions –15 and –16 did not significantly alter the Lrp footprinting pattern (data not shown).

Since the regions protected by IHF and CRP partially overlapped with those protected by Lrp, we tested the competition between these DNA-binding proteins on the non-template strand of the osmY promoter. After the simultaneous addition of IHF (50 nM) and CRP (50 nM), the specific protection patterns of both proteins were observed, showing that IHF and CRP binding were not mutually exclusive (Figure 3D, lane 7). In contrast, a mixture of CRP (50 nM) and Lrp (8 nM) resulted only in tight binding of CRP (Figure 3D, lane 8). Finally, when IHF (50 nM) and Lrp (8 nM) are added together, tight Lrp binding is observed whereas IHF binding is only slightly affected (Figure 3D, lane 5). Together, these results indicate that at the concentrations tested on linear template, Lrp is able to bind in the osmY promoter region even in the presence of IHF, while the presence of CRP leads to its exclusion from this promoter sequence.

EσS forms an open complex at osmY even in the presence of repressors

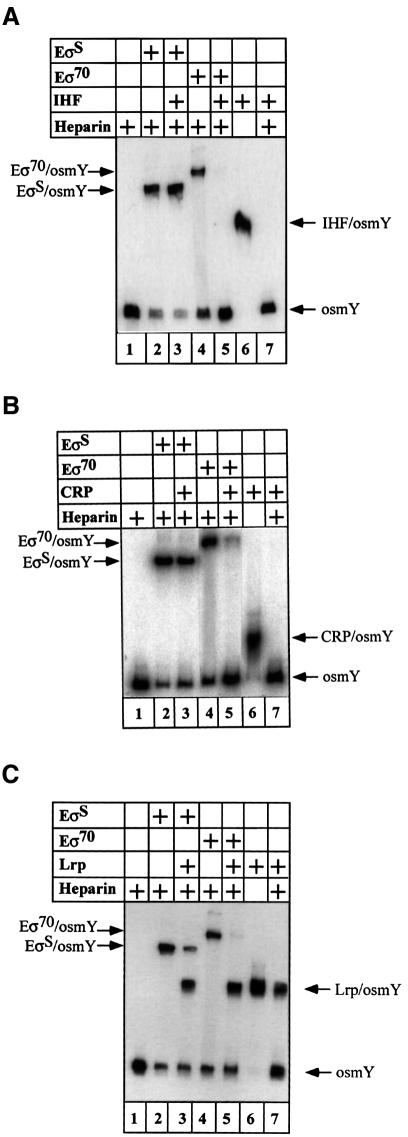

A simple approach was used to monitor in vitro the effect of these DNA-binding proteins on open complex formation with both forms of RNA polymerase. Open complexes with EσS or Eσ70 holoenzymes are known to be resistant to heparin challenge whereas binary complexes containing DNA and CRP or IHF are chased off quickly by this competitor (Figure 5A and B, lane 7). We first checked for the formation of heparin-resistant complexes with both holoenzymes. After a 20 min incubation of the osmY promoter with each reconstituted RNA polymerase (50 nM), 75% of heparin-resistant complex is observed with EσS (Figure 5, lane 2) and 60% with Eσ70 after heparin challenge (Figure 5, lane 4). In a second set of experiments, the repressor was incubated first with the osmY promoter without RNA polymerase. Full occupancy of CRP, IHF and Lrp DNA-binding sites is observed, as shown in Figure 5 (lane 6). As expected, the addition of heparin totally dissociates CRP–osmY and IHF–osmY complexes whereas the Lrp–osmY complex appears less sensitive (Figure 5, lane 7). We then added EσS or Eσ70 to these complexes for 20 min and followed the time course of formation of any heparin-resistant complex. A striking difference was observed: EσS is able to form a heparin-resistant complex on a promoter template pre-bound to IHF or cAMP–CRP (compare lane 3 in Figure 5A, B and C). Only in the presence of Lrp was open complex formation slightly reduced (Figure 5C, lane 3). In the case of Eσ70 RNA polymerase, however, binding to the osmY DNA fragment is highly inhibited by the presence of each repressor (Figure 5, lane 5). A simple conclusion can be drawn from these results: whatever the nature of the repressor, the formation of a heparin-resistant complex is hardly affected with EσS and strongly inhibited with Eσ70.

Fig. 5. Repressor effect on EσS and Eσ70 DNA binding and open complex formation. The radioactively labelled osmY promoter (0.2 nM) was mixed for 20 min at room temperature with the following repressors: (A) IHF (100 nM), (B) CRP (30 nM) and (C) Lrp (1.5 nM). EσS or Eσ70 holoenzymes (50 nM) were then added and incubated for 20 min at 37°C. The samples were heparin challenged before loading onto a 5% TBE polyacrylamide gel (except for lane 6). Lanes contain: DNA alone (1); DNA + EσS (2); DNA + Eσ70 (4); DNA + repressor + EσS (3); DNA + repressor + Eσ70 (5); DNA + repressor without heparin (6); or DNA + repressor with heparin (7).

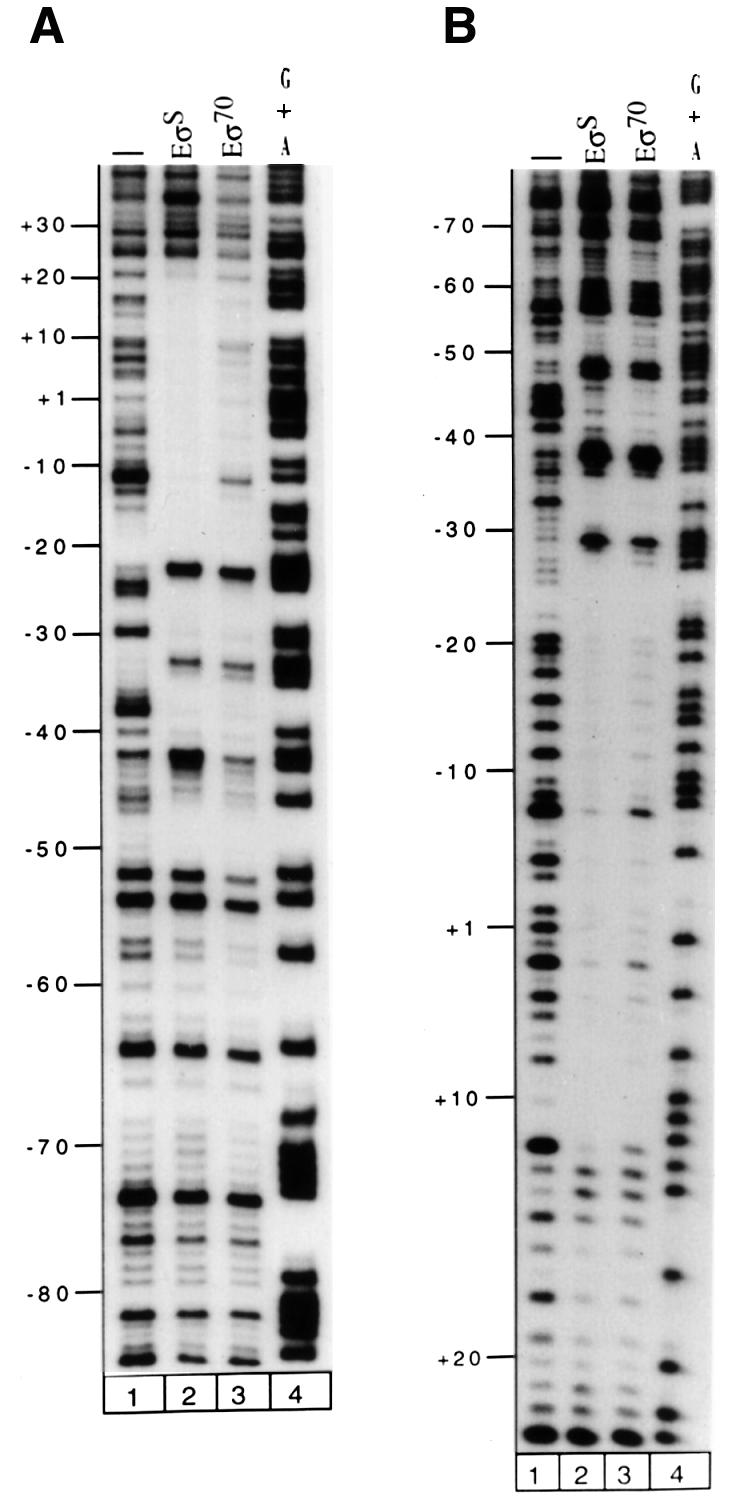

To confirm that EσS forms an open complex even in the presence of repressor, we used potassium permanganate reactivity. KMnO4 specifically reacts with thymine residues in single-stranded regions of DNA and has been used extensively to probe open complex formation (Sasse-Dwight and Gralla, 1989). When RNA polymerase forms an open complex at the osmY promoter, the melted region extends from –12 to –1 on the template strand for both holoenzymes (Figure 6, lanes 3 and 4). However, the reactivity pattern is different between both holoenzymes, with an enhanced reactivity of the thymines located in the downstream part of the transcription bubble observed with EσS. When CRP and IHF are added before RNA polymerase, open complex formation with EσS remains unaffected whereas it is decreased with Eσ70 (Figure 6, lanes 5–12). However, previous incubation with Lrp at 10 nM diminishes permanganate reactivity with both holoenzymes but to a greater extent with Eσ70 (Figure 6, lanes 13 and 14). At a higher Lrp concentration (50 nM), open complex formation is inhibited completely with both holoenzymes (Figure 6, lanes 15 and 16). These observations are in agreement with the previous gel shift experiments and strongly suggest that in the presence of repressors, EσS is more efficient at forming an open complex than Eσ70 at the osmY promoter.

Fig. 6. KMnO4 reactivity patterns of EσS and Eσ70 at the template strand of the osmY promoter in the absence and presence of repressors. Lane 1 shows a sequencing reaction for G + A and lane 2 represents DNA without protein treated with KMnO4. Except for these two lanes, odd and even numbers correspond to EσS and Eσ70, respectively. IHF (100 nM, lanes 5–6; 500 nM, lanes 7–8), CRP (5 nM, lanes 9–10; 25 nM, lanes 11–12) and Lrp (10 nM, lanes 13–14; 50 nM, lanes 15–16) were added to the osmY promoter before RNA polymerase. Reactive thymines, from –12 to –1, are indicated on the left of the gel.

The inhibitory effects of repressors on transcription activity are more drastic with Eσ70 than with EσS

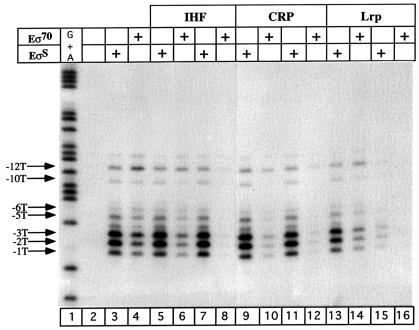

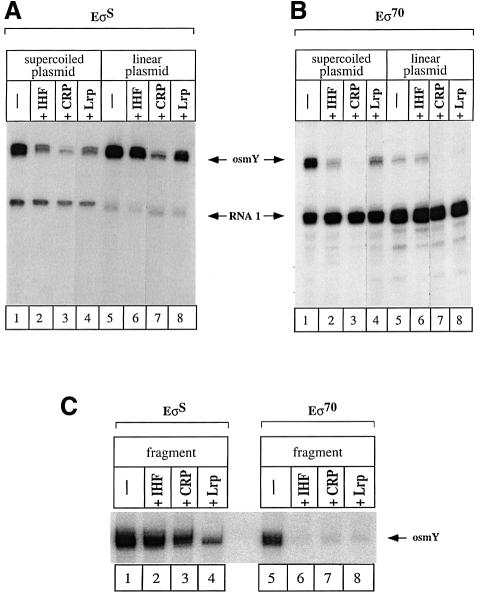

In order to test whether the inhibitory effects observed on open complex formation translate into different transcriptional activities, single round transcription assays were used. When transcription was performed from the osmY promoter in front of two rrnB transcriptional terminators on a supercoiled plasmid, both RNA polymerases were able to generate similar amounts of transcripts (Figure 7A and B, lane 1), in agreement with the results obtained by Ding et al. (1995). Binding of IHF, CRP or Lrp to the supercoiled osmY plasmid, before RNA polymerase addition and subsequent incubation for 20 min at 37°C, reduces transcription activity with either EσS or Eσ70 holoenzymes, indicating a direct inhibitory effect of each repressor on overall transcription activity (Figure 7A and B, compare lane 1 with lanes 2–4). Further, a significant differential effect is observed between the two RNA polymerases as Eσ70 is at least 2-fold more sensitive to repression than EσS (Figure 7A and B, lanes 1–4).

Fig. 7. Repressor effect on EσS- and Eσ70-dependent transcriptional activity. Single-round transcription experiments were performed using plasmid pJCDO2 (4 nM) (A and B) or a 343 bp osmY fragment (6 nM) (C) as template. (A and B) Supercoiled (lanes 1–4) or linearized (lanes 5–8) pJCD02 was incubated with holoenzyme (50 nM) containing either σS (A) or σ70 (B). (C) The 343 bp osmY fragment was incubated with holoenzyme (50 nM) containing either σS (lanes 1–4) or σ70 (lanes 5–8). In (A), (B) and (C), transcription was performed with holoenzyme alone (lanes 1 and 5) or with holoenzyme + IHF (lanes 2 and 6), cAMP–CRP (lanes 3 and 7) or Lrp (lanes 4 and 8). (D) Quantification of the relative intensities of the transcripts in (C) using a PhosphorImager.

An additional effect was observed when a linear plasmid cut with the unique restriction enzyme, AflIII, was used as a template. In the absence of repressors, Eσ70-mediated transcription from this template appears very weak as compared with EσS-mediated transcription (Figure 7A and B, lane 5). Thus, the state of DNA supercoiling significantly affects the rate of osmY transcription by Eσ70. This result agrees with previous in vitro transcription data obtained by Kusano et al. (1996). Due to this low actual transcriptional activity of Eσ70, the inhibitory effects of CRP, Lrp and IHF when added before RNA polymerase to the linear template were less visible but seemed qualitatively similar to those observed on supercoiled DNA. Restricting the length of the template used and therefore the competing effect of other promoters makes the effects even clearer. When transcription was performed on a small osmY fragment carrying the transcriptional terminator generated by PCR, the inhibitory effects of the repressors appeared very different for the two RNA polymerases (Figure 7C): IHF, CRP and Lrp affected Eσ70 activity more dramatically than EσS (Figure 7D).

Discussion

A paradox in the regulation of osmY and other σS-controlled genes

The osmY gene belongs to a class of genes that are dependent specifically on σS in vivo. However, like many other σS-dependent promoters, the osmY promoter can be transcribed efficiently by EσS and Eσ70 holoenzymes under standard in vitro conditions. Thus, one puzzling question is to understand why the osmY promoter is not expressed during exponential phase by Eσ70. Three DNA-binding proteins (IHF, CRP and Lrp) repress this promoter in vivo and in vitro (Figures 1 and 7; Lange et al., 1993). These proteins appear to affect osmY transcription by the Eσ70 RNA polymerase during exponential phase, since mutations that eliminate these proteins derepress osmY expression during this phase of the growth cycle (Lange et al., 1993). At the onset of the stationary phase, when σS is induced, the osmY promoter is activated even though the same set of repressors is still present (IHF and the cAMP–CRP complex even at increased concentrations; Azam et al., 1999).

In this study, we therefore asked whether repression exerted on EσS is weaker than on Eσ70 and by what molecular mechanisms this different effect is maintained. First, the repressor-binding sites as well as the positioning of RNA polymerases at osmY had to be identified in order to understand the inhibitory effect. Since transcription initiation is a multistep process that includes RNA polymerase binding, open complex formation, initiation of RNA synthesis and promoter clearance, it was then essential to investigate whether the efficiency of any of these steps at the osmY promoter was (i) different for the two holoenzymes and (ii) differentially affected by IHF, cAMP–CRP or Lrp in the presence of the two holoenzymes.

Transcription initiation at the osmY promoter by EσS and Eσ70 in the absence of the repressors

Our DNase footprint experiments show that EσS and Eσ70 both recognized the osmY promoter with globally the same pattern. However, the stationary phase holoenzyme protects especially the downstream part of the osmY promoter (from –30) whereas the exponential phase holoenzyme protects the upstream region (from –35) more strongly (Figure 2). Our results are in good agreement with previous observations suggesting that the –35 region as well as the –10 region are recognized by Eσ70 whereas EσS mainly recognizes the –10 region (Hiratsu et al., 1995; Kolb et al., 1995; Tanaka et al., 1995; Marschall et al., 1998; Colland et al., 1999).

Both holoenzymes are also able to form open complexes as demonstrated by heparin resistance (Figure 5) and permanganate footprinting (Figure 6). An enhanced permanganate reactivity of thymines in the downstream part was observed with EσS, suggesting a slightly different positioning of the transcription bubble, closer to the messenger start site in this case, as previously observed at the bolAP1 promoter (Nguyen and Burgess, 1997).

On supercoiled plasmid templates, EσS and Eσ70 produce comparable amounts of osmY transcripts. This was observed both after a 20 min pre-incubation between promoter and RNA polymerase as in Figure 7A and B (lane 1) and after shorter incubation times, i.e. transcription initiation is fast and occurs at similar rates for both holenzymes on supercoiled templates (data not shown). In contrast, on the linearized plasmid, Eσ70 produced far fewer transcripts than EσS, even after longer incubation periods, consistent with results previously reported (Kusano et al., 1996). This reduction in transcript synthesis is specific for Eσ70 transcription on linear osmY template and could also be observed, although less dramatically, on a smaller osmY fragment (Figure 7C, lanes 1 and 5). Again this difference in efficiency between EσS and Eσ70 persisted even after very long times of incubation of the osmY fragment with RNA polymerase. Since after 20 min incubation no significant difference between the two holoenzymes was detected in the formation of the heparin-resistant complexes, reactive to permanganate (Figures 5 and 6), our data suggest that the open complexes formed by EσS and Eσ70 have different abilities to initiate transcription. This hypothesis is supported by the reduced permanganate reactivity at positions –1, –2 and –3 of the Eσ70 complex, which could possibly mean that the +1 start is not as accessible to the incoming initiating ribonucleoside triphosphate as it is in the EσS complex. The different transcriptional activities of EσS and Eσ70 on linear templates might reflect a difference in their rates of promoter clearance on DNA that is not negatively supercoiled. This is certainly an attractive possibility that deserves further study.

The modulation of the Eσ70 activity by supercoiling may have a functional significance. While the entire chromosomal DNA is never completely relaxed, it is not excluded that, locally, certain promoter regions might become relatively relaxed by the action of topology-affecting ‘histone-like’ proteins such as H-NS or HU, and may therefore be transcribed less well by Eσ70 than by EσS. This also implies that changes in supercoiling on the one hand and the presence of DNA-binding proteins on the other, both of which may differentially affect transcription by EσS and Eσ70, should not be seen as completely independent parameters.

Positioning of the DNA-binding proteins cAMP–CRP, IHF and Lrp is consistent with their inhibitory role in the control of osmY

By assaying open complex formation and transcription in vitro, we demonstrated a direct and independent role of each DNA-binding protein (CRP, IHF and Lrp) in repressing osmY expression (Figure 7). Besides being specific gene regulators, all three proteins bend DNA by >80° and appear as global organizers of the nucleoid structure (Schultz et al., 1991; Wang and Calvo, 1993; Rice et al., 1996).

At the osmY promoter, the CRP-binding site is centred at position –12.5, overlapping the –10 region of the promoter. Thus, CRP-induced repression can be understood easily as a competition between CRP and RNA polymerase for DNA occupancy. Contrary to the proximal positioning of CRP, the IHF site is located in the far upstream region of the osmY promoter (Figure 4). The inhibitory effect of IHF at other promoters has been shown previously when it is bound at similar positions (Huang et al., 1990; Pratt et al., 1997). The IHF- and CRP-binding sites are separated by 86 bp, i.e. within a distance of eight B-DNA turns assuming a DNA helix repeat of 10.8 bp per turn, close to the in vivo situation. This positioning places the IHF- and CRP-induced bends in-phase and participates in the formation of a higher order curved DNA structure in conjunction with the intrinsic curvature of the osmY promoter sequence (Lange et al., 1993).

The Lrp protein binds the osmY promoter co-operatively and with high affinity to several sites, irrespective of the presence of leucine, as was observed previously for other promoter regions of Lrp-controlled genes (Wang and Calvo, 1993; Marschall et al., 1998; Zhi et al., 1999). Since a phasing of protected regions, extending over a region of >100 bp, was observed every 10–11 bp at osmY and at other promoters, it is likely that Lrp causes DNA to be wrapped around a core of Lrp molecules.

In summary, positioning of the binding sites for cAMP–CRP, IHF and Lrp is consistent with their repressing role in osmY control as well as with the formation of a complex nucleoprotein structure at this promoter (Lanzer and Bujard, 1988; Rojo, 1999).

The repressors differentially affect open complex formation by EσS and Eσ70

Both EσS and Eσ70 RNA polymerases initiate transcription from the osmY promoter in vitro (Figure 7; Ding et al., 1995), but a closer analysis demonstrates that the details of promoter binding and open complex formation are slightly different. IHF, CRP and Lrp not only inhibit osmY promoter activity, but our data indicate that these repressors differentially affect EσS and Eσ70 holoenzymes. The formation of heparin-resistant complexes, the melting of the DNA strands and the transcriptional activity (especially on supercoiled templates) are all less affected by the repressors when EσS is used rather than Eσ70 (Figures 5, 6 and 7). The same qualitative result was obtained irrespective of whether the repressors were added first or a mixture of the repressor and RNA polymerase was added to DNA (data not shown).

A number of mutually not exclusive mechanisms might be involved in this differential inhibitory effect of the repressors. (i) In contrast to Eσ70, which requires at least two anchoring regions (the –10 and –35 hexamers) for specific DNA–protein interactions (for a review see Helmann and deHaseth, 1999), the EσS RNA polymerase appears to recognize a smaller part of the promoter (such as an extended –10 region) (Colland et al., 1999). The mechanical constraints required for the proper phasing of the two recognition domains (Buckle et al., 1999) are thus more stringent for Eσ70 and therefore more sensitive to repressor action or to the formation of complex nucleoprotein structures in this region. (ii) Using dimethylsulfate (DMS) protection experiments, a striking difference is observed between both holoenzymes on the osmY template strand. G-14 is weakly protected in the major groove from DMS attack by EσS, but not by Eσ70, which generates a strong hyper-reactivity of this base (F.Colland and A.Kolb, unpublished results). Taking into account the known location of CRP on one side of the DNA in close contact with the minor groove at this position (Schultz et al., 1991; Kolb et al., 1993), it is possible that the first contacts between EσS and the osmY promoter occur on the DNA face opposite to CRP. This might ultimately lead to the removal of CRP from DNA by a mechanism similar to the displacement of nucleosomes by transcription factors (Kingston, 1997). This differential positioning of the two holoenzymes just upstream of the –10 region could explain why CRP represses Eσ70 more efficiently at osmY. (iii) Finally, specific protein–protein interactions between Eσ70 and the repressors might also take place and render Eσ70 inefficient at initiating transcription at the osmY promoter.

It should be noted that a differential effect on the activity of the two holoenzymes is not necessarily restricted to repressor action, nor has the favoured holoenzyme always to be EσS. At the csiD promoter, cAMP–CRP activates in concert with EσS, but not with Eσ70 (although it somewhat improves Eσ70 binding, it fails to stimulate open complex formation by Eσ70; Marschall et al., 1998). At the aidB and osmCp1 promoters, Lrp specifically interferes with activation by EσS (Landini et al., 1996; Bouvier et al., 1998). Similarly, at the alkA promoter, the Ada protein specifically shuts off EσS-dependent transcription (Landini et al., 1999).

Conclusion: generation of EσS selectivity at the osmY promoter

Intracellular salt concentration (Ding et al., 1995), negative global or local DNA supercoiling (Kusano et al., 1996; this study) or an anti-σ factor, such as Rsd, which may reduce the cellular Eσ70 concentration (Jishage and Ishihama, 1998, 1999), have been proposed to be involved in the ability of a promoter to discriminate between EσS and Eσ70, i.e. two RNA polymerase holoenzymes that exhibit very similar if not the same basic promoter sequence recognition. In addition, a possible involvement of DNA-binding proteins such as H-NS, Lrp and CRP has been suggested (Olsen et al., 1993; Arnqvist et al., 1994; Barth et al., 1995; Yamashino et al., 1995; Bouvier et al., 1998; Marschall et al., 1998; Hengge-Aronis, 1999). In this study, we demonstrate that the three global regulators IHF, CRP and Lrp play a major role in promoting or even generating σS selectivity at the osmY promoter by interfering more strongly with transcription initiation by Eσ70 than that by EσS. It is interesting to note that the expression of many σS-dependent genes is affected by various combinations of these and a few more regulatory proteins, most of which are histone-like proteins (Hengge-Aronis, 1996). Further studies will be needed to determine whether the modulation of σ factor specificity by these abundant nucleoid-associated proteins is a general rule at σS-dependent promoters.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and plasmids

All strains/alleles used for the experiment shown in Figure 1 were described in Lange et al. (1993) and were constructed by P1 transduction. Specific mutant alleles used were: Δ(nlpD-rpoS)360, lrp-201::Tn10, Δhip-3::cat and Δcrp96 (linked to zhd-732::Tn10). The osmY PCR fragment from –175 to +48 has been cloned in the HincII site of pJCD0 to generate pJCD02 (Marschall et al., 1998). The 343 bp osmY fragment used for transcription was synthesized by PCR with Pwo polymerase using pJCD02 as template, a specific osmY primer 5′-TTCAGTTCCACCAGACCC-3′ (from –175 to –158) and a plasmid primer 5′-GGATTTGTCCTACTCAGGAG-3′.

Protein purification and holoenzyme reconstitution

IHF was a gift of F.Boccard. Lrp proteins were received from J.Calvo and J.Rouvière-Yaniv. The E.coli CRP was prepared as described in Ghosaini et al. (1988). The σ70 and σS factors were purified from the overproducing strains M5219/pMRG8 and BL21(DE3)/pLysS/pETF, respectively, according to the described purification procedures (Gribskov and Burgess, 1983; Tanaka et al., 1995). Log-phase core enzyme was prepared according to Lederer et al. (1991). Reconstitution of active holoenzymes was achieved by incubating 1 vol. of 5 µM core enzyme with 2 vols of each σ factor at 10 µM for 20 min at 37°C (σ:core = 4). The reconstituted holoenzyme was then diluted at room temperature in buffer A [40 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 10 mM magnesium chloride, 100 mM potassium glutamate, 4 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and 500 µg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA)].

KMnO4 and DNase I footprinting

The labelled osmY fragment was generated by PCR with the primers 5′-TTCAGTTCCACCAGACCC-3′ and 5′-GATATCTACGCATTGAACG-3′ using a combination of one unlabelled primer and the second primer end-labelled with phage T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP (3000 Ci/mmol). This fragment was purified on a glass fibre column (High pure PCR product purification kit, used according to the recommendations of the manufacturer, Boerhinger Mannheim). Complexes with the labelled promoter region (at 2 nM final concentration) were formed for 20 min at 37°C in 15 µl of buffer A (for KMnO4, DTT was omitted) using each repressor and/or reconstituted RNA polymerase (200 nM final concentration). In one set of experiments, 2.5 µl of DNase I solution (1 µg/ml in 10 mM Tris–HCl, 10 mM magnesium chloride, 10 mM calcium chloride, 125 mM potassium chloride) were added and incubated at 37°C for 20 s, or for 30 s when RNA polymerase was present in the mixture. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 200 µl of a solution containing 0.4 M sodium acetate, 2.5 mM EDTA, 50 µg/ml calf thymus DNA, and put on ice. In the other set, 1.5 µl of KMnO4 solution (50 mM) was added to the complexes for 30 s at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by adding 2.5 µl of 2-mercaptoethanol (2 M). Then, all the samples were phenol extracted and precipitated with ethanol. With the KMnO4 samples, the ethanol precipitates were resuspended in 100 µl of piperidine (1 M), heated at 90°C for 30 min and evaporated until dryness. Then, 20 µl of water were added and evaporated (twice). KMnO4 and DNase I samples were resuspended in 5 µl of 20 mM EDTA in formamide containing xylene cyanol and bromophenol blue and loaded on a 7% denaturing polyacrylamide gel.

Gel retardation assays

Repressors [CRP (30 nM), IHF (100 nM) and Lrp (1.5 nM)] were complexed to the radioactively labelled osmY promoter (0.2 nM) for 20 min at room temperature in buffer A. Eσ70 or EσS reconstituted holoenzymes (50 nM) were then added and incubated for 20 min at 37°C in a final volume of 10 µl. After addition of heparin (55 µg/ml), the mixture was loaded onto a 5% native polyacrylamide gel. The gel was fixed, dried before being autoradiographed and quantified using a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

Run-off transcription assays

Single-round transcription by reconstituted RNA polymerase was carried out under the standard conditions described previously, using supercoiled plasmid (pJCD02 prepared from an overnight culture of a recA1 strain), linear plasmid (pJCD02 digested with AflIII) or a 343 bp osmY fragment generated by PCR using Pwo polymerase. DNA plasmid (8 nM), previously incubated with IHF (250 nM), cAMP–CRP (100 nM), Lrp (200 nM) or buffer at room temperature for 20 min, was next incubated with each reconstituted holoenzyme (50 nM) in buffer A at 37°C for 20 min in 10 µl final volume. Alternatively, the 343 bp osmY fragment (12 nM), previously incubated with IHF (250 nM), cAMP–CRP (50 nM), Lrp (50 nM) or buffer at room temperature for 20 min was used as template for transcription under the same conditions. Elongation was started by the addition of 5 µl of a pre-warmed mixture containing 600 µM ATP, GTP and CTP, 30 µM UTP, 0.5 µCi of [α-32P]UTP and 600 µg/ml heparin to the template–polymerase mix and allowed to proceed for 5 min at 37°C. Reactions were stopped by the addition of 20 mM EDTA in formamide containing xylene cyanol and bromophenol blue. After heating to 65°C, samples were subjected to electrophoresis on 7% sequencing gels. Run-off products were quantified using a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Henri Buc for his constant interest, and to Gilbert Orsini and Bianca Sclavi for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Frédéric Boccard, Joseph Calvo and Josette Rouvière-Yaniv for the gifts of IHF and Lrp proteins. We also thank Akira Ishihama for providing the pETF plasmid. F.C. is a recipient of a PhD fellowship from the MNRE (Paris VI). This work was supported by grants from the French Ministère de l’Education Nationale, de la Recherche et de la Technologie (Programme de Recherche Fondamentale en Microbiologie, Maladies Infectieuses et Parasitaires) as well as by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Priority program ‘Regulatory Networks in Bacteria’, HE 1556/5), the State of Baden-Württemberg (Landesforschungspreis) and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

References

- Arnqvist A., Olsen,A. and Normark,S. (1994) σS-dependent growth-phase induction of the csgBA promoter in Escherichia coli can be achieved in vivo by σ70 in the absence of the nucleoid-associated protein H-NS. Mol. Microbiol., 13, 1021–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aviv M., Giladi,H., Schreiber,G., Oppenheim,A.B. and Glaser,G. (1994) Expression of the genes coding for the Escherichia coli integration host factor are controlled by growth phase, rpoS, ppGpp and by autoregulation Mol. Microbiol., 14, 1021–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azam T.A., Iwata,A., Nishimura,A., Ueda,S. and Ishihama,A. (1999) Growth phase-dependent variation in protein composition of the Escherichia coli nucleoid. J. Bacteriol., 181, 6361–6370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balke V.L. and Gralla,J.D. (1987) Changes in the linking number of supercoiled DNA accompany growth transitions in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 169, 4499–4506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros M., Kusano,S., Ishihama,A. and Vicente,M. (1998) The ftsQ1p gearbox promoter of Escherichia coli is a major σS-dependent promoter in the ddlB-ftsA region. Mol. Microbiol., 30, 419–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth M., Marschall,C., Muffler,A., Fischer,D. and Hengge-Aronis,R. (1995) Role for the histone-like protein H-NS in growth phase-dependent and osmotic regulation of σS and many σS-dependent genes in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 177, 3455–3464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordes P., Repoila,F., Kolb,A. and Gutierrez,C. (2000) Involvement of differential efficiency of transcription by EσS and Eσ70 RNA polymerase holoenzymes in growth phase regulation of the Escherichia coli osmE promoter. Mol. Microbiol., 35, 845–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouvier J., Gordia,S., Kampmann,G., Lange,R., Hengge-Aronis,R. and Gutierrez,C. (1998) Interplay between global regulators of Escherichia coli: effect of RpoS, Lrp and H-NS on transcription of the gene osmC. Mol. Microbiol., 28, 971–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckle M., Pemberton,I.K., Jacquet,M.A. and Buc,H. (1999) The kinetics of σ subunit directed promoter recognition by E.coli RNA polymerase. J. Mol. Biol., 285, 955–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colland F., Fujita,N., Kotlarz,D., Bown,J.A., Meares,C.F., Ishihama,A. and Kolb,A. (1999) Positioning of σS, the stationary phase σ factor, in Escherichia coli RNA polymerase-promoter open complexes. EMBO J., 18, 4049–4059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig N.L. and Nash,H.A. (1984) E.coli integration host factor binds to specific sites in DNA. Cell, 39, 707–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y., Midkiff,M.A., Wang,Q. and Calvo,J.M. (1996) The leucine-responsive regulatory protein (Lrp) from Escherichia coli. Stoichiometry and minimal requirements for binding to DNA. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 6611–6617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Q., Kusano,S., Villarejo,M. and Ishihama,A. (1995) Promoter selectivity control of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase by ionic strength: differential recognition of osmoregulated promoters by EσD and EσS holoenzymes. Mol. Microbiol., 16, 649–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman D.I. (1988) Integration host factor: a protein for all reasons. Cell, 55, 545–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosaini L.R., Brown,A.M. and Sturtevant,J.M. (1988) Scanning calorimetric study of the thermal unfolding of catabolite activator protein from Escherichia coli in the absence and presence of cyclic mononucleotides. Biochemistry, 27, 5257–5261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich J.A., Schwartz,M.L. and McClure,W.R. (1990) Searching for and predicting the activity of sites for DNA binding proteins: compilation and analysis of the binding sites for Escherichia coli integration host factor (IHF). Nucleic Acids Res., 18, 4993–5000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribskov M. and Burgess,R.R. (1983) Overexpression and purification of the σ subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. Gene, 26, 109–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmann J.D. and deHaseth,P.L. (1999) Protein–nucleic acid interactions during open complex formation investigated by systematic alteration of the protein and DNA binding partners. Biochemistry, 38, 5959–5967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengge-Aronis R. (1996) Regulation of gene expression during entry into stationary phase. In Neidhardt,F.C. (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology. ASM Press, Washington, DC, pp. 1497–1512. [Google Scholar]

- Hengge-Aronis R. (1999) Interplay of global regulators and cell physiology in the general stress response of Escherichia coli. Curr. Opin. Microbiol., 2, 148–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengge-Aronis R., Lange,R., Henneberg,N. and Fischer,D. (1993) Osmotic regulation of rpoS-dependent genes in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 175, 259–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiratsu K., Shinagawa,H. and Makino,K. (1995) Mode of promoter recognition by the Escherichia coli RNA polymerase holoenzyme containing the σS subunit: identification of the recognition sequence of the fic promoter. Mol. Microbiol., 18, 841–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L., Tsui,P. and Freundlich,M. (1990) Integration host factor is a negative effector of in vivo and in vitro expression of ompC in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 172, 5293–5298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihama A. (1999) Modulation of the nucleoid, the transcription apparatus and the translation machinery in bacteria for stationary phase survival. Genes Cells, 4, 135–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jishage M. and Ishihama,A. (1998) A stationary phase protein in Escherichia coli with binding activity to the major σ subunit of RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 4953–4958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jishage M. and Ishihama,A. (1999) Transcriptional organization and in vivo role of the E.coli rsd gene, encoding the regulator of RNA polymerase σD. J. Bacteriol., 181, 3768–3776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston R.E. (1997) A snapshot of a dynamic nuclear building block. Nature Struct. Biol., 4, 763–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb A., Busby,S., Buc,H., Garges,S. and Adhya,S. (1993) Transcriptional regulation by cAMP and its receptor protein. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 62, 749–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb A., Kotlarz,D., Kusano,S. and Ishihama,A. (1995) Selectivity of the Escherichia coli RNA polymerase Eσ38 for overlapping promoters and ability to support CRP activation. Nucleic Acids Res., 23, 819–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusano S., Ding,Q., Fujita,N. and Ishihama,A. (1996) Promoter selectivity of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase Eσ70 and Eσ38 holoenzymes. Effect of DNA supercoiling. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 1998–2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landgraf J.R., Wu,J. and Calvo,J.M. (1996) Effects of nutrition and growth rate on Lrp levels in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 178, 6930–6936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landini P. and Busby,S.J. (1999) Expression of the Escherichia coli ada regulon in stationary phase: evidence for rpoS-dependent negative regulation of alkA transcription J. Bacteriol., 181, 6836–6839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landini P.J., Hajec,L.I., Nguyen,L.H., Burgess,R.R. and Volkert,M.R. (1996) The leucine-responsive regulatory protein (Lrp) acts as a specific repressor for σ S-dependent transcription of the Escherichia coli aidB gene. Mol. Microbiol., 20, 947–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange R. and Hengge-Aronis,R. (1991) Identification of a central regulator of stationary-phase gene expression in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol., 5, 49–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange R. and Hengge-Aronis,R. (1994) The cellular concentration of the σS subunit of RNA polymerase in Escherichia coli is controlled at the levels of transcription, translation and protein stability. Genes Dev., 8, 1600–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange R., Barth,M. and Hengge-Aronis,R. (1993) Complex transcriptional control of the σS-dependent stationary-phase-induced and osmotically regulated osmY (csi-5) gene suggests novel roles for Lrp, cyclic AMP (cAMP) receptor protein–cAMP complex and integration host factor in the stationary-phase response of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 175, 7910–7917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanzer M. and Bujard,H. (1988) Promoters largely determine the efficiency of repressor action. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 85, 8973–8977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lederer H., Mortensen,K., May,R.P., Baer,G., Crespi,H.L., Dersch,D. and Heumann,H. (1991) Spatial arrangement of σ factor and core enzyme of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. A neutron solution scattering study. J. Mol. Biol., 219, 747–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewen P.C. and Hengge-Aronis,R. (1994) The role of the σ factor σS (KatF) in bacterial global regulation. Annu. Rev. Microbiol., 48, 53–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonetto M., Gribskov,M. and Gross,C.A. (1992) The σ70 family: sequence conservation and evolutionary relationships. J. Bacteriol., 174, 3843–3849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marschall C., Labrousse,V., Kreimer,M., Weichart,D., Kolb,A. and Hengge-Aronis,R. (1998) Molecular analysis of the regulation of csiD, a carbon starvation-inducible gene in Escherichia coli that is exclusively dependent on σS and requires activation by cAMP–CRP. J. Mol. Biol., 276, 339–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxam A.M. and Gilbert,W. (1977) A new method for sequencing DNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 74, 560–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey M.R. and Loewen,P.C. (1989) Nucleotide sequence of katF of Escherichia coli suggests KatF protein is a novel σ transcription factor. Nucleic Acids Res., 17, 9979–9991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman E.B. and Lin,R. (1995) Leucine-responsive regulatory protein: a global regulator of gene expression in E.coli. Annu. Rev. Microbiol., 49, 747–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen L.H. and Burgess,R.R. (1997) Comparative analysis of the interactions of Escherichia coli σS and σ70 RNA polymerase holoenzyme with the stationary-phase-specific bolAp1 promoter. Biochemistry, 36, 1748–1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen L.H., Jensen,D.B., Thompson,N.E., Gentry,D.R. and Burgess,R.R. (1993) In vitro functional characterization of overproduced Escherichia coli katF/rpoS gene product. Biochemistry, 32, 11112–11117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen A., Arnqvist,A., Hammar,M., Sukupolvi,S. and Normark,S. (1993) The RpoS σ factor relieves H-NS-mediated transcriptional repression of csgA, the subunit gene of fibronectin-binding curli in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol., 7, 523–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt T.S., Steiner,T., Feldman,L.S., Walker,K.A. and Osuna,R. (1997) Deletion analysis of the fis promoter region in Escherichia coli: antagonistic effects of integration host factor and Fis. J. Bacteriol., 179, 6367–6377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice P.A., Yang,S., Mizuuchi,K. and Nash,H.A. (1996) Crystal structure of an IHF–DNA complex: a protein-induced DNA U-turn. Cell, 87, 1295–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojo F. (1999) Repression of transcription initiation in bacteria. J. Bacteriol., 181, 2987–2991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasse-Dwight S. and Gralla,J.D. (1989) KMnO4 as a probe for lac promoter DNA melting and mechanism in vivo. J. Biol. Chem., 264, 8074–8081. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz S.C., Shields,G.C. and Steitz,T.A. (1991) Crystal structure of a CAP–DNA complex: the DNA is bent by 90°. Science, 253, 1001–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegele D.A. and Kolter,R. (1992) Life after log. J. Bacteriol., 174, 345–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K., Takayanagi,Y., Fujita,N., Ishihama,A. and Takahashi,H. (1993) Heterogeneity of the principal σ factor in Escherichia coli: the rpoS gene product, σ38, is a second principal σ factor of RNA polymerase in stationary-phase Escherichia coli.Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 90, 3511–3515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K., Kusano,S., Fujita,N., Ishihama,A. and Takahashi,H. (1995) Promoter determinants for Escherichia coli RNA polymerase holoenzyme containing σ38 (the rpoS gene product). Nucleic Acids Res., 23, 827–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q. and Calvo,J.M. (1993) Lrp, a major regulatory protein in Escherichia coli, bends DNA and can organize the assembly of a higher-order nucleoprotein structure. EMBO J., 12, 2495–2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weichart D., Lange,R., Henneberg,N. and Hengge-Aronis,R. (1993) Identification and characterization of stationary phase-inducible genes in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol., 10, 407–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese D.E., Ernsting,B.R., Blumenthal,R.M. and Matthews,R.G. (1997) A nucleoprotein activation complex between the leucine-responsive regulatory protein and DNA upstream of the gltBDF operon in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol., 270, 152–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashino T., Ueguchi,C. and Mizuno,T. (1995) Quantitative control of the stationary phase-specific σ factor, σS, in Escherichia coli: involvement of the nucleoid protein H-NS. EMBO J., 14, 594–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim H.H. and Villarejo,M. (1992) osmY, a new hyperosmotically inducible gene, encodes a periplasmic protein in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 174, 3637–3644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim H.H., Brems,R.L. and Villarejo,M. (1994) Molecular characterization of the promoter of osmY, an rpoS-dependent gene. J. Bacteriol., 176, 100–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhi J., Mathew,E. and Freundlich,M. (1999) Lrp binds to two regions in the dadAX promoter region of Escherichia coli to repress and activate transcription directly. Mol. Microbiol., 32, 29–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]