Abstract

The ISWI ATPase of Drosophila is a molecular engine that can drive a range of nucleosome remodelling reactions in vitro. ISWI is important for cell viability, developmental gene expression and chromosome structure. It interacts with other proteins to form several distinct nucleosome remodelling machines. The chromatin accessibility complex (CHRAC) is a biochemical entity containing ISWI in association with several other proteins. Here we report on the identification of the two smallest CHRAC subunits, CHRAC-14 and CHRAC-16. They contain histone fold domains most closely related to those found in sequence-specific transcription factors NF-YB and NF-YC, respectively. CHRAC-14 and CHRAC-16 interact directly with each other as well as with ISWI, and are associated with functionally active CHRAC. The developmental expression profiles of both subunits suggest specialized roles in chromatin remodelling reactions in the early embryo for both histone fold subunits.

Keywords: CHRAC/chromatin/histone fold/ISWI/nucleosome

Introduction

The packaging of the eukaryotic genome into a complex chromatin structure requires molecular mechanisms that allow regulatory molecules to gain access to DNA. Biochemical and genetic studies have identified several multiprotein complexes, including the yeast SWI/SNF complex, which assist the DNA binding of nuclear proteins by opening inaccessible chromatin structures in an ATP-dependent reaction (Imbalzano, 1998; Guschin and Wolffe, 1999; Kingston and Narlikar, 1999; Muchardt and Yaniv, 1999). Biochemical studies in Drosophila have identified three distinct nucleosome remodelling complexes, nucleosome remodelling factor (NURF), chromatin accessibility complex (CHRAC) and the ATP-utilizing chromatin assembly and remodelling factor (ACF) (Tsukiyama and Wu, 1995; Ito et al., 1997; Varga-Weisz et al., 1997), which differ in protein composition and function but all contain ISWI, an ATPase of the SWI2/SNF2 superfamily (Eisen et al., 1995; see also http://www.stanford.edu/~jeisen/SNF2/snf2.html). ISWI, the catalytic core of these nucleosome remodelling machines (Corona et al., 1999), is able to catalyse nucleosome sliding on DNA, without disruption or trans-displacement of the histone octamer (Hamiche et al., 1999; Längst et al., 1999; Travers, 1999). The precise mechanism of this induced nucleosome mobility is unclear, but the reaction requires significant energy input which is derived from ATP hydrolysis. ISWI-containing remodelling factors are thought to function by establishing a dynamic state of chromatin, characterized by an increased mobility of nucleosomes. Chromatin that has been rendered ‘fluid’ can be accessed much better by DNA-binding proteins in a variety of in vitro binding assays (Tsukiyama and Wu, 1995; Ito et al., 1997; Mizuguchi et al., 1997; Varga-Weisz et al., 1997; Alexiadis et al., 1998; Corona et al., 1999; reviewed by Kingston and Narlikar, 1999).

The presence of ISWI in different chromatin remodelling machines highlights the modular nature of these complexes and suggests that the different molecular environments of ISWI may correspond to different functional contexts (Varga-Weisz and Becker, 1998). Genetic studies in Drosophila have revealed that ISWI is required for cell viability, developmental gene expression and the maintenance of higher order chromatin structure. (Deuring et al., 2000), but it is unclear at present which of the ISWI-containing remodelling machines contribute to which aspect of the complex phenotype. Further understanding of the in vivo role and specificity of ISWI may come from characterization of the proteins associated with ISWI in CHRAC and other chromatin remodelling complexes. These proteins may serve to regulate or target ISWI activity, perhaps defining the physiological context within which the nucleosome remodelling reaction takes place.

Two ISWI-associated proteins have so far been identified as NURF subunits: NURF-55 is a WD repeat protein identical to the 55 kDa subunit of the Drosophila chromatin assembly factor (CAF-1; Martinez-Balbas et al., 1998). Since WD repeat proteins related to NURF-55 are also associated with histone deacetylase and histone acetylase complexes, NURF-55 may function as a general, common adaptor for protein complexes involved in chromatin metabolism (Martinez-Balbas et al., 1998). NURF-38, an inorganic pyrophosphatase, may have a structural or regulatory role in the complex (Gdula et al., 1998). In ACF, ISWI activity is modulated by Acf1, a Drosophila protein related to the human WSTF protein, deleted in Williams’ syndrome (Lu et al., 1998; Ito et al., 1999).

We have defined CHRAC as a biochemical entity containing ISWI, topoisomerase II and three other subunits of molecular masses 14, 16 and 175 kDa (Varga-Weisz et al., 1997). The potential regulatory importance of CHRAC-induced access to nucleosomal DNA in vitro is best illustrated by the finding that CHRAC was able to trigger the initiation of replication by facilitating the access of T-antigen to a nucleosomal origin of replication (Alexiadis et al., 1998). CHRAC may also facilitate the repositioning of nucleosomes that is required to establish an active ribosomal DNA promoter (Längst et al., 1998). CHRAC-induced nucleosome sliding may also be important during chromatin assembly when the mobilization of nucleosomes allows their rearrangement into a regular nucleosomal array (Varga-Weisz et al., 1997; Corona et al., 1999).

Here we report on the identification and initial characterization of the two smallest subunits of CHRAC, CHRAC-14 and -16. These Drosophila proteins show a striking similarity to the histone fold domains of the mammalian transcription factors NF-YB (CBF-A) and NF-YC (CBF-C), respectively (Maity and de Crombrugghe, 1998). Our data suggest that CHRAC-14 and CHRAC- 16 heteromerize via their histone folds and are able to form a complex with ISWI. We provide biochemical evidence that both proteins are associated with functionally active CHRAC in vivo. CHRAC-14 and -16 are most abundant in early embryos and their expression is rapidly down-regulated as development proceeds. This developmental expression profile points to a specific role for CHRAC in the early embryo, which is characterized by rapid nuclear division cycles. Histone fold proteins so far have been identified in the NF-Y transcription factors, in the general transcription factor TFIID and in histone acetyl transferase complexes. Our study now adds nucleosome remodelling to the growing list of reactions in which histone fold proteins participate.

Results

CHRAC-14 and -16 are histone fold proteins related to NF-YB and NF-YC

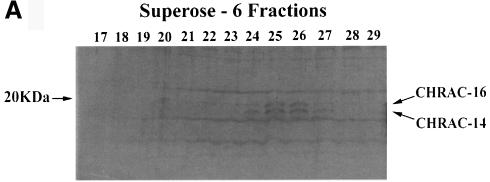

Polypeptides with molecular masses of 14 and 16 kDa repeatedly copurify with CHRAC to apparent homogeneity (Varga-Weisz et al., 1997). A Superose-6 gel filtration profile of the last step of the CHRAC purification shows a tight correlation of these two proteins with the peak fractions 25 and 26 of CHRAC (arrows in Figure 1A). On the basis of this correlation, we tentatively defined these proteins as CHRAC subunits, CHRAC-14 and -16, respectively. Peptide sequences were obtained from CHRAC-14 and -16 polypeptides by mass spectrometry microsequencing (Figure 1B) and used in a TBLASTN search at the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project database. The search identified two distinct perfectly matching expressed sequence tag (EST) clots, as well as two P1 genomic clones, encoding novel proteins containing all peptides retrieved by mass spectrometric analysis (Figure 1C). Using the sequence information from the EST clots as well as the available genomic DNA sequence, we deduced the full open reading frame of CHRAC-14 and -16. A BLAST search of the CHRAC-14 and -16 sequences identified extensive homology to the histone fold domains of the transcription factors NF-YB and NF-YC (also known as CBF-A and CBF-C, respectively), as well as with the archaeal histone-like protein Hmf2.

Fig. 1. Purification and identification of CHRAC-14 and -16. (A) Fractions from the last Superose-6 gel filtration purification step of CHRAC (Varga-Weisz et al., 1997) were resolved by 15% SDS–PAGE and stained with silver. Arrows indicate the two small proteins that co-fractionate with CHRAC activity, which peaks in fractions 25 and 26 (data not shown). (B) Summary of peptide identity information on CHRAC-14 and -16, after electrospray tandem mass spectrometric analysis. (C) Results of DNA sequence obtained with a TBLASTN search against the nucleic acid database present at Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project database, using the peptide information on CHRAC-14 and -16. CHRAC-14 ESTs GM01831 and GM04761 can also be found at the NCBI database (http://www3.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) under accession numbers AI237921 and AA695912, respectively. CHRAC-16 ESTs LD33780 and LD06740 can be found at the NCBI database under accession numbers AI061700 and AA263589, respectively.

NF-Y factors belong to a family of proteins, conserved from yeast to humans (see Maity and de Crombrugghe, 1998, for review), that associate into heteromeric complexes able to bind the CCAAT box, a common cis-acting element in regulatory regions of many eukaryotic genes (see Mantovani, 1998, for review). CCAAT-binding factors generally consist of A subunits (CBF-A or NF-YB), B subunits (CBF-B or NF-YA) and C subunits (CBF-C or NF-YC). Dimerization of NF-YB and NF-YC via their histone fold motifs is a prerequisite for the association of NF-YA, which in turn is required for interaction of the NF-Y–CBF complex with the CCAAT box (Sinha et al., 1995).

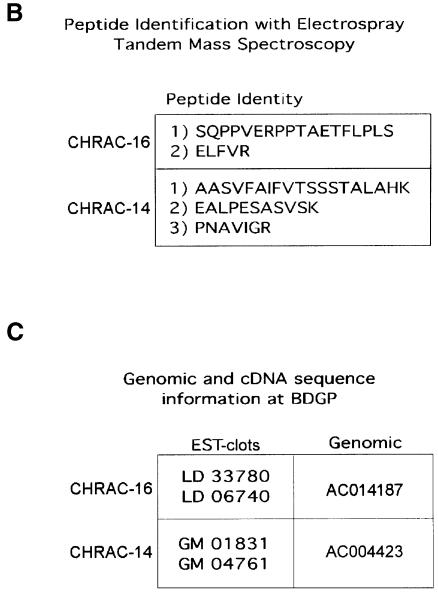

A CLUSTALW alignment revealed a striking similarity between the putative histone fold domains of CHRAC-14 and NF-YB and less prominent similarity between the corresponding domains of CHRAC-16 and NF-YC (Figure 2A). Histone folds are commonly classified by their similarity to the corresponding domains of histones themselves. By this classification, NF-YC shows an H2A-related histone fold [see Baxevanis et al. (1995) and Ouzounis and Kyrpides (1996) for a discussion of their relationship to histones H3 and H4], while the fold of NF-YB resembles that of histone H2B (Sinha et al., 1996). Both histone folds are also distantly related to the archaeal histone-like protein HMf2 (Kim et al., 1996; Sinha et al., 1996). Taken together, our data suggest that CHRAC-14 and -16 are novel histone fold proteins of the H2B and H2A classes, respectively. Secondary structure prediction suggests that CHRAC-14 and -16 consist of the three helices and two loops that constitute the histone fold, with relatively short N- and C-terminal extensions (Figure 2B and C).

Fig. 2. CHRAC-14 and -16 are histone fold proteins. (A) Amino acid sequence alignments of CHRAC-14 and -16 with the histone fold motifs of histones H2B and H2A and of the histone-fold proteins NF-YB and NF-YC. Amino acid identities are displayed between the lines, as are conservative changes (+). Shading identifies the α-helixes, separated by loop regions (lines), according to the structural data of the nucleosome (Luger et al., 1997). (B and C) Alignments of (B) CHRAC-14 and (C) CHRAC-16 with their human (hEST), mouse (mEST) and zebrafish (zEST) counterparts. Protein sequences were obtained by back-translation of the corresponding ESTs. Vertebrate ESTs homologous to CHRAC-14 can be found at the NCBI database (http://www3.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) under the following accession numbers: z-EST, AI416300; mEST, AI386008; hEST, AW250660. Vertebrate ESTs homologous to CHRAC-16 can be found at the NCBI database under the following accession numbers: z-EST, AI878165; mEST, AI195704; hEST, AI353705. The EMBL database accession Nos of CHRAC-14 and -16 are AJ271141 and AJ271142, respectively.

A TBLASTN search against the NCBI EST database revealed close homologues of CHRAC-14 and -16 in zebrafish, mouse and humans (Figure 2B and C), and in Arabidopsis thaliana and Schizosaccharomyces pombe (data not shown). No obvious homologues were found in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Remarkably, whereas the similarity of CHRAC-14 and -16 with NF-YB and NF-YC is only confined to the histone-fold motif, the zebrafish, mouse and human EST clots show identities throughout the entire length of CHRAC-14 and -16 (Figure 2B and C).

The BLAST search did not reveal any other NF-Y-like proteins in Drosophila. No obvious CCAAT-binding sites are present in Drosophila promoters, and all attempts to identify biochemically an NF-Y complex in flies failed, so Drosophila may well lack those factors altogether (Li and Liao, 1992). Because CHRAC-14 and -16 differ significantly from NF-Y subunits, both in size and in sequences outside of the histone fold domains, but have homologues in zebrafish, mammals, S.pombe and plants, we suggest that CHRAC-14 and -16 and their homologues define a novel class of histone fold proteins with distinct functions.

CHRAC-14 and -16 are bona fide subunits of CHRAC

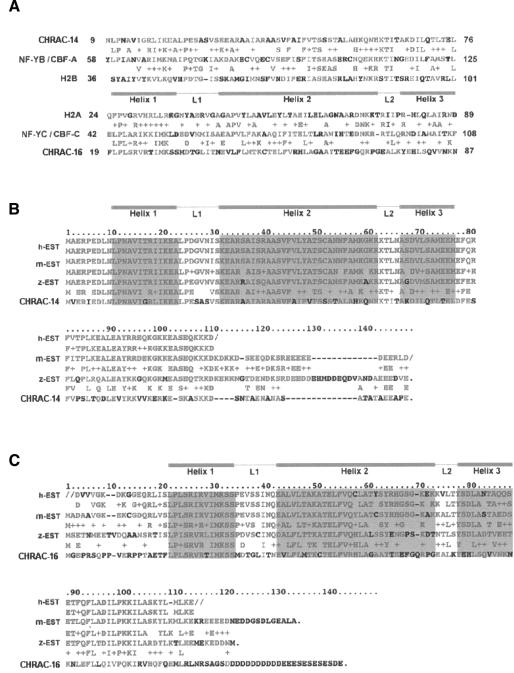

In order to confirm that CHRAC-14 and -16 are bona fide subunits of CHRAC, we raised polyclonal antisera against CHRAC-14 in the form of a glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein, expressed in Escherichia coli. We obtained useful antisera allowing the detection of CHRAC-14 (αp14), but could not express CHRAC-16 in a similar manner, and thus could not obtain an equivalent reagent for its detection. We failed to raise antisera against CHRAC-16-derived peptides that allowed the unambiguous identification of CHRAC-16 in Drosophila extracts. However, very recently, we were able to co-express CHRAC-16 with GST–CHRAC-14 in bacteria (see below) and obtained an antiserum recognizing both proteins simultaneously from an immunization with CHRAC-14 and -16 together (αp14/16). This antiserum allowed us to follow the copurification of CHRAC-14 and -16 with ISWI and p175 through several columns (data not shown). Figure 3A shows, as an example, the Superose-6 gel filtration profile of CHRAC which has been purified over four columns (see Materials and methods). The single peak of CHRAC-14 and -16 coincides well with the peak of ISWI. Immunoprecipitation of CHRAC-14 and -16 with αp14/16 from crude embryo extracts co-precipitated ISWI (Figure 3B). Conversely, the immunoprecipitate obtained with an antibody raised against ISWI also contained CHRAC-14 and -16 (Figure 3B). However, the use of the αp14/16 serum to visualize the two subunits in crude extracts is rather limited due to prominent cross-reactivities, particularly in the higher molecular weight range. Gel filtration of crude cytoplasmic extracts from preblastoderm embryos or nuclear extracts from postblastoderm embryos showed 50 and 90% of the bands corresponding to CHRAC-14–CHRAC-16 in ISWI- containing fractions, respectively, whereas the remaining protein resided in fractions of lower molecular masses (data not shown).

Fig. 3. CHRAC-14 and -16 co-purify with ISWI. (A) Superose 6 size exclusion chromatography of highly purified CHRAC. Input material (I) after the hydroxyapatite column (see Materials and methods) and eluted fractions were electrophoresed on 6% (upper panel) or 18% (lower panel) polyacrylamide gels, transferred to PVDF membrane and analysed by western blotting using an antiserum against ISWI or an antiserum raised against CHRAC-14 and -16 together (p14/p16). Input (In) and fraction numbers are indicated above the gel. (B) Interactions of CHRAC-14–CHRAC-16 with ISWI in vivo. Protein from crude extracts was immunoprecipitated with anti-ISWI and anti-p14/16 antibodies as well as preimmune serum (P). An aliquot of the input material (I) was resolved in parallel with immunoprecipitated protein by PAGE and detected by Western blotting as in (A).

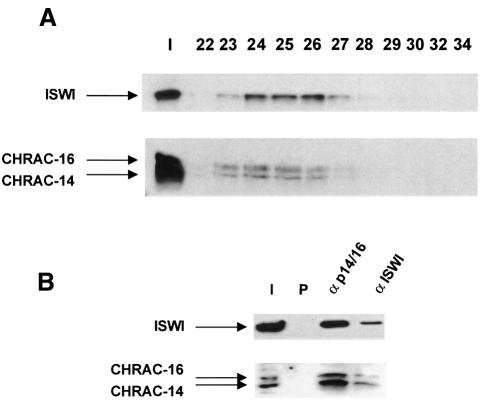

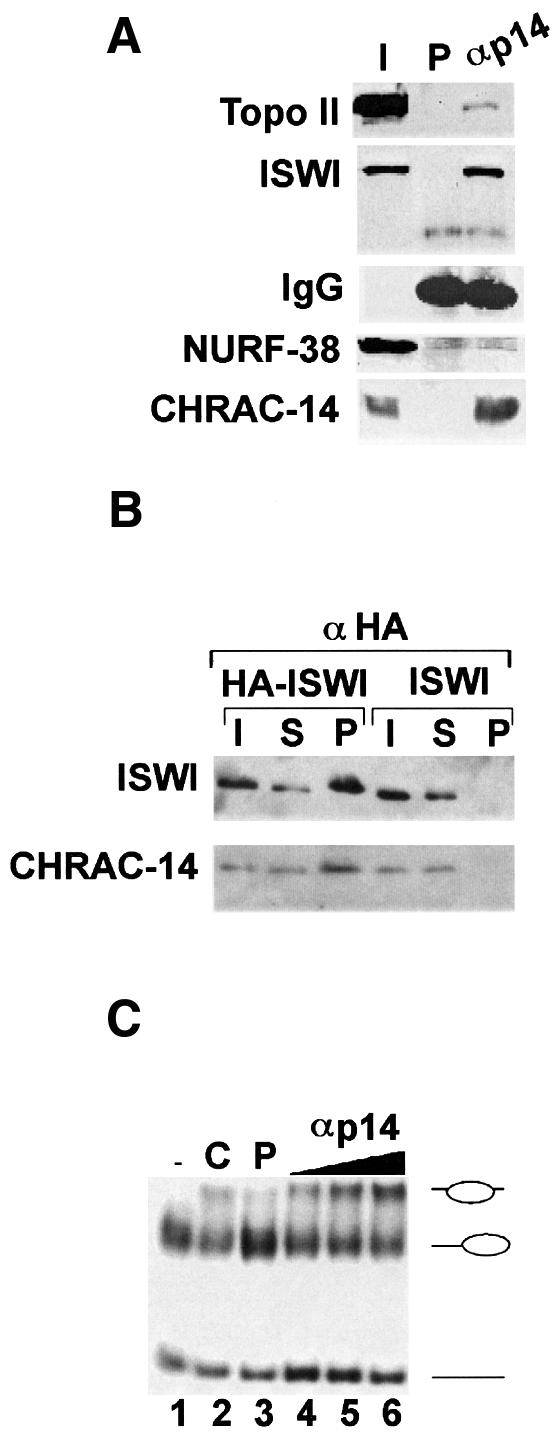

The lower band of the pair was detected by the antiserum raised against GST–CHRAC-14 (αp14), confirming the identity of the two bands. This antiserum was also used in immunoprecipitations from embryo extracts and associated proteins were detected by western blotting (Figure 4A). Immunoprecipitation of CHRAC-14 efficiently pulled down ISWI, as well as a small amount of topoisomerase II (see Discussion). Parallel reactions with preimmune serum established the specificity of the precipitation. Notably, the NURF-specific subunit NURF-38 (Gdula et al., 1998) was not precipitated under these conditions (Figure 4A). To demonstrate the interaction between ISWI and CHRAC-14 by yet another strategy, we co-immunoprecipitated ISWI and CHRAC-14 from extracts prepared from Drosophila embryos bearing a transgene encoding haemagglutinin (HA) epitope-tagged ISWI (HA-ISWI; Deuring et al., 2000). Embryo extracts derived from a Drosophila strain lacking the HA-ISWI transgene provided a negative control. Anti-HA antibody specifically immunoprecipitated CHRAC-14 and ISWI from extracts containing HA-tagged ISWI, but not from the control extracts (Figure 4B), providing further evidence that CHRAC-14 is physically associated with ISWI in the Drosophila embryo.

Fig. 4. CHRAC-14 is associated with active CHRAC. (A) Drosophila embryo nuclear proteins were immunoprecipitated with rabbit polyclonal anti-CHRAC-14 serum or with an equivalent amount of preimmune serum (P). Immunoprecipitated protein was analysed by SDS–PAGE and western blotting with antibodies against topoisomerase II, ISWI, NURF-38 and CHRAC-14. I, 5% of input material; P, total pellet with preimmune serum; αM, total pellet with anti-CHRAC-14 serum. (B) A rabbit anti-HA antibody was used to immunoprecipitate HA-ISWI from embryo extracts derived from a transgenic fly line containing an ectopic copy of ISWI tagged with the HA epitope. I, 20% of input material; S, supernatant after immunoprecipitation; P, total pellet. Immunoprecipitated materials were analysed by SDS–PAGE and western blotting with anti-ISWI and anti-CHRAC-14 antibodies. (C) Drosophila embryo nuclear extracts were incubated with anti-rabbit Dynal beads preincubated with preimmune or anti-CHRAC-14 serum. Precipitated complexes were rigorously washed and resuspended in 40 µl of EX-100 buffer. Twenty microlitres of control (preimmune) beads (lane 3) and 5, 10 or 20 µl (lanes 4–6, respectively) of anti-CHRAC-14 beads were incubated with gel-purified end-positioned nucleosomes for 90 min at 26°C. The nucleosome sliding reactions were loaded on to a native polyacrylamide gel. Lane 1 (–), input mononucleosomes; lane 2, a control sliding reaction catalysed by partially purified CHRAC (C).

CHRAC-14 is associated with active CHRAC

In order to test whether the association of CHRAC-14 with ISWI was compatible with an active remodelling machine, we made use of a previously established nucleosome sliding assay. This assay visualizes the ability of CHRAC to mobilize a nucleosome positioned at a fragment end to slide to a more central position on a short DNA fragment (Längst et al., 1999). Anti-CHRAC-14 antiserum was immobilized on paramagnetic beads and used to ‘fish out’ CHRAC-14 and associated factors from a crude embryo extract. Immobilized factors were then tested for CHRAC activity in the nucleosome sliding assay. Incubation of the affinity-purified protein with the nucleosomal substrate led to an ATP-dependent movement of the nucleosome to the more central position (Figure 4C, lanes 1 and 4–6), as determined by earlier mapping (Längst et al., 1999). Apparently, the CHRAC-14-specific antiserum was able to retrieve CHRAC from the extract, as defined by an activity able to induce nucleosome sliding from a peripheral to a central position (Längst et al., 1999). As a control for specificity of the reaction we used paramagnetic beads coated with preimmune serum (Figure 4C, lane 3). Taken together, these experiments document the association of CHRAC-14 with ISWI in the context of an active nucleosome remodelling machine.

CHRAC-14 and -16 form a heteromeric complex

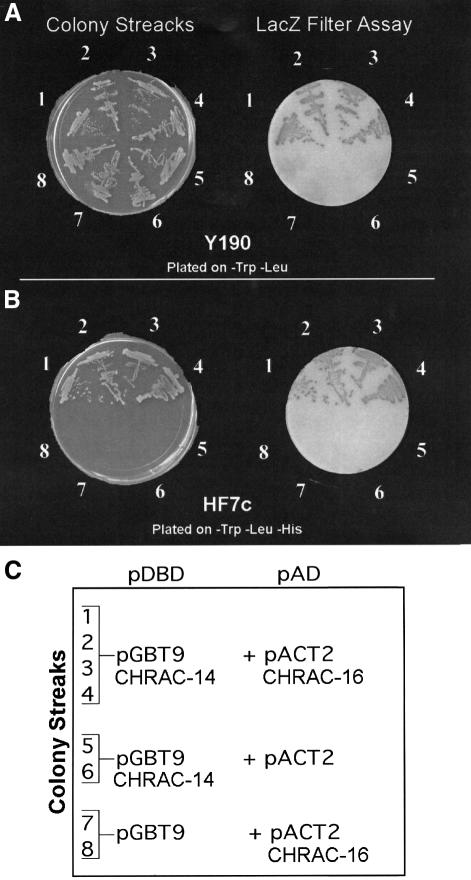

Without exception, histone fold proteins have been found to associate with other histone fold factors as homo- or heterodimers. Because we found CHRAC-14 and -16 with similar stoichiometry in CHRAC (Figure 1A), we considered that the two histone fold proteins might interact. We first tested this hypothesis by performing a GAL4-based yeast two-hybrid interaction test (Fields and Song, 1989). Full-length CHRAC-14 and -16 were fused in-frame to the DNA-binding domain (DBD) and activation domain (AD) of GAL4, respectively. Interaction of the two hybrid proteins in yeast reconstitutes a transcription factor able to activate transcription of two reporter genes, the HIS3 gene and the lacZ gene, each under the control of a Gal1 promoter. Under these circumstances, survival of yeast under conditions of histidine starvation can be directly correlated to the extent to which the HIS3 promoter is activated, providing a direct assessment of the interaction between CHRAC-14 and -16. Growth tests in the absence of a histidine supplement and β-galactosidase filter assays (Figure 5A and B, samples 1–4) clearly reveal an interaction between CHRAC-14 and -16 in yeast. Omission of one partner leads to lack of growth on starvation medium and no significant β-galactosidase activity (Figure 5A and B, samples 5–8).

Fig. 5. Interaction of CHRAC-14 and -16 in a yeast two-hybrid assay. CHRAC-14 and -16 coding sequences were cloned into the yeast two-hybrid plasmids pGBT9 and pACT2, respectively, and transformed according to the scheme shown in (C) into yeast strains Y190 (A) and HF7c (B). β-galactosidase filter assays and growth tests in the absence of histidine [compare streaks 1–4 with control streaks 5–8 in (A) and (B)] revealed an interaction between CHRAC-14 and -16.

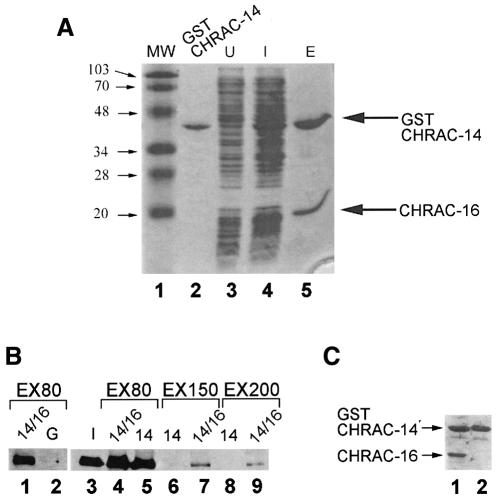

To verify that the interaction between CHRAC-14 and -16 is direct, and not mediated by an endogenous yeast factor, we examined the interactions between recombinant CHRAC-14 and -16 proteins in vitro. Expression of CHRAC-14 as a GST fusion protein in E.coli, followed by purification on a glutathione affinity column, yielded abundant soluble protein (Figure 4, lane 2). By contrast, we were unable to express soluble CHRAC-16 independently in E.coli, despite many attempts. We obtained high yields of soluble CHRAC-16 if we co-expressed CHRAC-16 together with GST–CHRAC-14. Apparently, CHRAC-16 was rendered soluble through interaction with GST–CHRAC-14, since purification of GST–CHRAC-14 on a glutathione affinity matrix resulted in co-purification of CHRAC-16 (Figure 6A, lane 5). Taken together, our results demonstrate that CHRAC-14 and -16 can form heteromers in vivo and in vitro.

Fig. 6. (A) Expression and interaction of CHRAC-14 and -16 in E.coli. Plasmids coding for CHRAC-14, as a GST fusion, and CHRAC-16 were co-expressed in E.coli. Upon induction with IPTG, two major bands, indicated by arrows, appeared in the total bacterial lysate (compare lanes 3 and 4). These bands, corresponding to GST–CHRAC-14 and CHRAC-16, co-eluted upon glutathione–Sepharose bead purification. Proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE on an 8% gel and stained with Coomassie Blue. Molecular masses (MW) in kilodaltons are indicated with arrows in lane 1. Lane 3, protein from uninduced control lysate; lane 4, protein from induced lysate; lane 5, protein eluted from the affinity resin. (B) CHRAC-14 and -16 physically interact with ISWI in vitro. About 20 µl of GST (G), GST–CHRAC-14 (14) or GST–CHRAC-14 bound with CHRAC-16 (14/16) were immobilized on Sepharose 4B–glutathione resin and incubated with 1.5 µg of purified recombinant ISWI. Bound material was challenged with wash buffers containing 80, 150 and 200 mM of monovalent cations, as indicated (EX80, EX150 and EX200, respectively). Bound protein was analysed by SDS–PAGE and western blotting with anti-ISWI antibody. (C) The integrity of the affinity resins was unaffected by the high stringency washes. An aliquot of each resin was processed as above and bound CHRAC-14 and -16 were visualized by SDS–PAGE and Coomassie staining (lanes 1 and 2).

CHRAC-14 and -16 interact directly with ISWI

To test whether the interaction between CHRAC-14–CHRAC-16 and ISWI, observed in immunoprecipitation reactions (Figures 3 and 4), was direct and not mediated by other CHRAC components, we expressed GST–CHRAC-14 alone or together with CHRAC-16 in E.coli as before and created an affinity resin by adsorbing the proteins to the Sepharose 4B–glutathione via the GST. ISWI was passed through the columns and the bound protein was challenged with washes of increasing stringency by raising the ionic strength. Whereas a control GST resin did not retain ISWI (Figure 6B, lane 2), the ATPase interacted efficiently with immobilized CHRAC-14 or CHRAC-14–CHRAC-16 complexes and resisted washes with buffers containing 80 mM monovalent cations (Figure 6B; compare lane 2 with lanes 4 and 5). Increasing the stringency of the wash to 150 or 200 mM monovalent cations weakened considerably the interaction of ISWI with both affinity resins. Remarkably, ISWI was still able to associate with the CHRAC-14–CHRAC-16 complex under conditions of increased stringency where it fails to interact with CHRAC-14 alone (Figure 6B; compare lanes 6 and 7 with lanes 8 and 9). The integrity of the affinity resins is unaffected by high salt washes (Figure 6B): GST–CHRAC-14 and GST–CHRAC-14–CHRAC-16 remain column-bound under those conditions. In summary, we conclude that ISWI can interact directly with CHRAC-14 and this interaction is further stabilized by associated CHRAC-16.

CHRAC-14 and -16 expression is tightly developmentally controlled

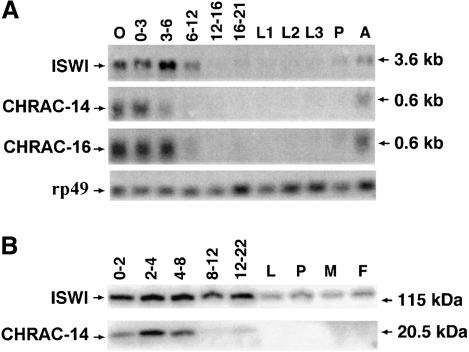

DNA probes specific for CHRAC-14 and -16 were used to visualize the corresponding mRNAs during fly development (Figure 7A). The expression profile in developmentally staged RNAs was compared with that of ISWI RNA, which is maternally provided and highly abundant in early embryos, but decreases considerably during later developmental stages (Elfring et al., 1994). Likewise, CHRAC-14 and -16 RNAs are abundant in oocytes and embryos up to ∼6 h of development but are sharply down-regulated later to ∼5–10% of the preblastoderm levels (Figure 7A, 6–12 h). The protein profiles obtained from western blot analyses of staged total protein preparations also document the developmental regulation of CHRAC-14. While ISWI is particularly abundant throughout embryogenesis, but clearly present in larvae, pupae and adults (Figure 7B), as observed earlier (Tsukiyama et al., 1995), the CHRAC-14 protein levels drop sharply a few hours into embryonic development (Figure 7B).

Fig. 7. CHRAC-14 and -16 are developmentally regulated subunits of CHRAC. (A) Northern blot analysis of ISWI, CHRAC-14 and -16 was performed with total RNA isolated at different stages of Drosophila development, probed with the corresponding cDNA probes. As a control for equivalent loading and integrity of the RNA, the blot was also hybridized with an rp49 probe (O’Connell and Rosbash, 1984). The numbers above the lanes indicate the age of the embryos in hours. L1, L2 and L3, first, second and third instar larvae, respectively; P, pupae; A, adults (mixture of males and females. (B) Western blot analysis of ISWI and CHRAC-14 was performed with equivalent amounts of total soluble protein derived from Drosophila at the indicated stages of development. Samples were subjected to SDS–PAGE and western blotting with anti-ISWI and anti-CHRAC-14 antibody. The labelling of the stages is as in (A). M, adult male flies; F, adult female flies.

Discussion

We have identified a novel pair of histone fold proteins, CHRAC-14 and -16, as subunits of CHRAC, a nucleosome remodelling factor. Homologous proteins exist in yeast, plants and throughout the animal kingdom, suggesting an important function of these proteins. Importantly, their association with the nucleosome remodelling ATPase ISWI is also conserved. Varga-Weisz and colleagues (Poot et al., 2000) have identified the human homologues of CHRAC-14 and -16 (huCHRAC-15 and -17) associated with the human homologue of ISWI in a complex that appears to be human CHRAC. Based on sequence analysis, we suggest that CHRAC-14 and -16 and their homologues define a novel class of histone fold proteins, most closely related to the heterodimer pairs NF-YB– NF-YC and yeast HAP3–HAP5, but significantly diverged from them. We do not know the stoichiometry with which the CHRAC-14–CHRAC-16 heteromer associates with ISWI.

The association of CHRAC-14 and -16 with ISWI suggest that they may target or modulate the activity of the latter. Consistent with a possible functional interaction between CHRAC-14 and ISWI, a large deficiency spanning CHRAC-14 and other genes in salivary gland chromosome region 29C1-2 and 30C8-9 enhances the eye defects that result from partial loss of ISWI function (J.Armstrong, M.Ding and J.Tamkun, personal communication). The isolation and characterization of mutations in CHRAC-14 and -16 will be necessary to provide conclusive evidence for a genetic interaction. Importantly, CHRAC-14 and -16 associate with ISWI in functionally active CHRAC since the nucleosome sliding activity can be retrieved from a crude extract with an antibody against CHRAC-14. This observation argues against a repressive role of these histone fold proteins in nucleosome remodelling.

The identification of the two small subunits has advanced the molecular definition of CHRAC significantly. Recently, and in agreement with data presented by Poot et al. (2000), we identified the largest subunit of CHRAC as Acf1 (S.Ferrari, A.Eberharter, T.Straub, G.Längst, P.D.Varga-Weisz and P.B.Becker, manuscript in preparation) which has previously been found to associate with ISWI to form the dimeric ACF (Ito et al., 1999). Based on extensive co-fractionation with CHRAC activity and co-immunoprecipitations with ISWI, we previously concluded that topoisomerase II was also a subunit of CHRAC (Varga-Weisz et al., 1997). However, we recently realized that topoisomerase II could be chromatographically separated from CHRAC without affecting the integrity of the remaining complex or the nucleosome sliding activity quantitatively or qualitatively (Ferrari,S., Eberharter,A. et al., manuscript in preparation). Because of this, we have to reconsider the suitability of topoisomerase II as a diagnostic subunit of CHRAC. As it stands, CHRAC can best be defined as ISWI and Acf1 (= ACF), associated with the two histone fold proteins, CHRAC-14 and -16. The two small subunits, therefore, have important diagnostic value since they distinguish CHRAC from ACF.

There are various ways in which the association of the small CHRAC subunits with ISWI could modulate the nucleosome remodelling activity of the ATPase in various ways. The CHRAC-14–CHRAC-16 heteromers could constitute a structural element that ties the complex together or targets CHRAC to sites of action through further interactions. They could also provide a non-specific DNA binding surface, stabilizing the interaction of the complex with chromatin. Finally, they could be involved in the mechanism of nucleosome remodelling.

The histone fold is a particularly successful heterodimerization motif in chromatin-associated proteins. Histone fold proteins vary considerably in size and usually also contain other functional domains. Diverse as they are, histone fold heterodimers can all make further contacts with other proteins, building higher order complexes of regulatory importance. Thus, TBP-associated factors (TAFs) featuring the histone fold are integral components of the general transcription factor TFIID, where they transmit cues from interacting activators (Hoffmann et al., 1996; Xie et al., 1996; Birck et al., 1998; Gangloff et al., 2000; for review see Burley et al., 1997). The same proteins are also constituents of the large histone acetyl transferase complexes SAGA and PCAF (Grant et al., 1998; Ogryzko et al., 1998; Gangloff et al., 2000; for review see Struhl and Moqtaderi, 1998). Interaction of the histone domain factors NF-YB and NF-YC with NF-YA forms the CCAAT-specific transcription factor NF-Y, which activates transcription from many promoters (for review see Mantovani, 1998). Alternatively, NF-YB– NF-YC may also interact with TBP, although the functional importance of this interaction is less clear (Bellorini et al., 1997). The paired histone fold domains of NF-Y may also interact with the GCN5 and PCAF histone acetyl transferase (Currie, 1998). By contrast, the more transient association of the histone fold heterodimer NC2α–NC2β (Dr1–DRAP1) with TBP leads to repression of transcription (Inostroza et al., 1992; Goppelt et al., 1996; Mermelstein et al., 1996). Histone folds of opposite ‘polarity’ may thus have structural roles: by stable dimerization into a compact unit and further interaction with other components, they may help to assemble higher order complexes, the functional significance being determined by specific features of the interaction. The interaction with other factors may involve the paired histone fold motif itself, since even small proteins which mainly consist of the histone folds, like histones themselves or the CHRAC-14–CHRAC-16 pair, are still able to bind other proteins. In the case of CHRAC-14–CHRAC-16 we have documented direct interactions with the nucleosome remodelling ATPase ISWI. Binding of CHRAC-14 to paramagnetic beads via a polyclonal antiserum targets CHRAC activity to the bead surface. CHRAC-14–CHRAC-16 may thus serve to integrate ISWI into a proper functional context.

The induction of nucleosome sliding may involve contacts with both histones and the associated DNA to disrupt interactions locally. Due to their similarity to other DNA-associated histone fold pairs, CHRAC-14 and -16 are excellent candidates for providing a surface for non-specific DNA interaction. Key residues that are involved in H2A–H2B interactions with DNA in the nucleosome (Figure 2A), such as S53 of H2B, and R29, R35, V43 and K74 of H2A (Luger and Richmond, 1998), are identical or at least conservatively substituted in CHRAC-14 and -16, respectively. Molecular modelling of a putative CHRAC-14–CHRAC-16 dimer, using the histone H2A–H2B dimer as a structural frame, confirms the potential of a putative CHRAC-14–CHARC-16 dimer to interact with DNA (J.Brzeski and P.B.Becker, unpublished observation). Consistent with a role of a CHRAC-14–CHARC-16 dimer in contacting DNA, Varga-Weisz and colleagues recently demonstrated sequence-independent DNA binding of the human homologues, huCHRAC-15/-17 (Poot et al., 2000). In this study, the heteromeric complex of huCHRAC-15 and -17 interacted with DNA, whereas each individual protein was unable to do so, arguing for the involvement of a specific DNA binding fold and against a non-specific electrostatic interaction. While the functional relevance of this observation in the context of intact CHRAC remains to be established, it is likely that the DNA-binding surfaces of CHRAC-14–CHRAC-16 will be exposed to DNA, as DNA binding of other histone fold modules is compatible with additional protein interactions. The histone folds of NF-YB and NF-YC contribute to specific DNA binding in the context of the NF-Y heterotrimer (Zemzoumi et al., 1999). Positive charges on the histone octamer that define the path of DNA over the particle surface are at least partially conserved in TAFs that may contribute to stable interaction of TFIID with DNA (Xie et al., 1996). In the context of the SAGA complex, depletion of the H2B-like TAFII68 leads to reduced histone acetyl transferase activity on nucleosomal substrates, indicating that this TAF may be involved in recognizing the nucleosomal substrate (Grant et al., 1998).

In order to use the information stored in chromatin, the accessibility of DNA has to be altered locally while the overall packaging of DNA must be maintained. Histone fold proteins may contribute to this fine balance by replacing histones in order to alter local chromatin organization transiently. For example, it has been proposed that histone fold TAFs constitute an octameric structure which may serve as a specialized chromatin component marking active promoters (Hoffmann et al., 1997) although the situation is likely to be more complex and dynamic (Birck et al., 1998). Remarkably, chimeric particles formed by interaction of histone fold proteins with histones are possible; recently, Mantovani and colleagues not only assembled particles consisting of histone H3–H4 tetramers and the paired histone fold domains of NF-YB and NF-YC in vitro (Caretti et al., 1999), but also established that similar interactions are possible between the human homologues of CHRAC-14 and -16 (called YBL1 and YCL1 in the Mantovani laboratory) and histones H3 and H4 (F.Bolognese, C.Imbriano, G.Caretti and R.Mantovani, submitted). It is, therefore, conceivable that CHRAC-14 and -16 in CHRAC may stabilize an intermediate of the nucleosome remodelling process, either by serving as acceptors for transiently dislodged histones or by replacing H2A–H2B dimers in the nucleosome. We recently established that, in principle, nucleosome sliding can be triggered by ISWI itself (Corona et al., 1999), but simply adding bacterially expressed CHRAC-14–CHRAC16 to nucleosome sliding reactions does not have a qualitative effect (G.Längst, unpublished observation). However, it is still possible that the presence of CHRAC-14–CHRAC-16 might quantitatively alter the kinetics of the sliding reaction and that the reconstitution of a functional interaction between CHRAC subunits requires the development of more sophisticated biochemical assays.

The presence of CHRAC-14 and -16 is strongly regulated during Drosophila development. Both proteins are maternally provided; they are most abundant during early embryonic development and strikingly down- regulated to be minimally expressed in pupal and adult stages. This pattern is reminiscent of that of components of the Drosophila origin recognition complex (ORC), which is involved in the initiation of DNA replication. ORC proteins are also abundant in preblastoderm embryos and strongly down-regulated during development (Chesnokov et al., 1999), a pattern which correlates with developmental stages in which replication is the dominant nuclear process. This correlation leads us to speculate about a role for CHRAC in nuclear division in its widest sense. CHRAC may be directly involved in facilitating replication of chromosomal DNA, consistent with biochemical data (Alexiadis et al., 1998), or in alterations of higher order chromatin structure leading to condensation of chromatin into metaphase chromosomes or decondensation after telophase. The currently available data are not consistent with a role of CHRAC in general transcription of chromatin templates (Mizuguchi et al., 1997; Di Croce et al., 1999; Deuring et al., 2000).

The developmental regulation of CHRAC-14 and -16 implies that CHRAC, defined as a particular molecular context that incorporates the nucleosome remodelling activity of ISWI, is restricted to defined developmental stages. Whether this is due to its involvement in nuclear division or other processes that characterize early embryonic development remains an interesting topic for future investigations.

Materials and methods

Mass spectrometry

Proteins were proteolytically trypsinized in the gel (Shevchenko et al., 1996). Extracted peptides were purified on a 100 nl R2 Poros microcolumn and eluted in 1 µl of 60% methanol/5% formic acid into a nanoelectrospray capillary. The peptides were sequenced on an API III triple quadrupole instrument (PE-Sciex) equipped with an upgraded collision cell and the nanoelectrospray ion source (Wilm and Mann, 1996). Partial sequences of peptides from CHRAC-16 retrieved from a single tandem mass spectrometric experiment were sufficient to identify EST clones in the Berkeley database. Comparison between the complete peptide sequence from the database and the fragment spectra confirmed that these peptides had indeed been fragmented. The peptides from the CHRAC-14 protein were sequenced de novo using the esterification method (Hunt et al., 1986; Wilm et al., 1996). Details of the analysis are available upon request.

DNA and protein sequence analysis

DNA and protein sequences data were retrieved from the Entrez server (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Entrez) and the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project database (http://www.fruitfly.org/). DNA and protein sequence analysis and assembly were performed with the Lasergene DNASTAR and GCG 10.0 software packages. The BLAST software package (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST) was used to find DNA and protein sequence homology. Multiple sequence alignments were generated with CLUSTALX software. Protein secondary structure and 3D modelling predictions were done at the SWISS-MODEL server (http://www.expasy.ch/swissmod/SWISS-MODEL.html).

Cloning of CHRAC-14 and -16

The cDNA coding for the full-length CHRAC-14 and -16 proteins was cloned by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) in the pCRII-TOPO vector (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Primers for RT–PCR (CHRAC-141/U: 5′-ATGGATCCATGGTCGAGCGCATCGAGGAT-3′; CHRAC-141/L: 5′-CGAATTCTCACTCGGGGGCTTCCTCTGC-3′; CHRAC-161/U: 5′-GGTCTCCCATGGGCGAACCAAGGAG-3′; CHRAC-161/L: 5′-GGTCTCGGATCCCTATTCATCAGACTCC-3′) were designed using the sequence information derived from the EST clots. The sequences derived from the cloned cDNAs were identical to the sequences of the EST clots and genomic data and resulted in one unique open reading frame. The DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank database accession Nos of CHRAC-14 and -16 are AJ271141 and AJ271142, respectively.

Expression of recombinant CHRAC-14 and -16 in E.coli

The DNA fragment released by digestion of plasmid pCRII-CHRAC-14 with BamHI and EcoRI was cloned into BamHI- and EcoRI-cut expression vector pGEX2T (Pharmacia). The DNA fragment released by digestion of pCRII-CHRAC-16 with BsaI was cloned into the NcoI and BamHI sites of the expression vector pET24-d(+) (Novagen). Plasmid pGEX2T-CHRAC-14 alone or with pET24-d-CHRAC-16 was transformed into E.coli expression strain ER2566 (NEB). Single colonies were grown on LB medium containing 100 µg/ml ampicillin and 50 µg/ml kanamycin, until they had reached an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6 at 37°C and induced with 0.3 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 30°C for 2 h. Purification of GST–CHRAC-14 alone or co-purification of GST–CHRAC-14 with CHRAC-16 protein was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol for the GST purification module kit (Pharmacia).

Yeast two-hybrid interaction test

Primers CHRAC-142/U (5′-CGAATTCATGGTCGAGCGCATCGAGGAT-3′) and CHRAC-142/L (5′-ATGGATCCTCGGGGGCTTCCTCTGCTGT-3′) were designed to PCR-amplify CHRAC-14 cDNA from the pCRII-CHRAC-14 plasmid. The amplified fragment was digested with EcoRI and BamHI and cloned into the EcoRI and BamHI sites of the yeast DNA binding domain plasmid (pDBD) pGBT9 (Clontech). The DNA fragment resulting from the digestion of plasmid pCRII-CHRAC-16 with BsaI was cloned into the NcoI and BamHI sites of the yeast DNA activation domain plasmid (pAD) pACT2 (Clontech). Yeast strain Y190 and HF7c were co-transformed with pDBDs and pADs according to the scheme in Figure 3C. Co-transformants in strain Y190 were tested for growth on SD solid medium lacking tryptophan and leucine, and those in strain HF7c on SD solid medium lacking tryptophan, leucine and histidine. lacZ expression was monitored by colony-lift filter assay (Clontech).

Antibodies

Polyclonal antibodies against CHRAC-14 were generated by immunization of rabbits with recombinant GST–CHRAC-14 and RIBI adjuvant. Affinity purification was performed with immobilized pure CHRAC-14 antigen on PVDF membrane. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against the CHRAC-14–CHRAC-16 heterodimer were generated against recombinant GST–CHRAC-14 and CHRAC-16 co-expressed in E.coli and purified via the GST tag on CHRAC-14, using Titer Max (Sigma) as adjuvant. Anti-HA antibody, derived from ascites fluid, and anti-ISWI antibody were provided by J.Tamkun. The NURF-38 and topoisomerase II antibodies were kindly provided by C.Wu and D.Arndt-Jovin, respectively.

Purification of CHRAC from Drosophila embryos

Nuclear extracts were prepared from 0–24 h old embryos as before (Varga-Weisz et al., 1997). CHRAC devoid of topoisomerase II (Figure 3) was prepared by a novel srategy detailed elsewhere (S.Ferrari, A.Eberharter, T.Straub, G.Längst, P.D.Varga-Weisz and P.D.Becker, in preparation), Details can be obtained upon request. In short, extracts were fractionated on a BioRex 70 column (Bio-Rad) equilibrated in buffer C150 [10 mM HEPES pH 7.6, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EGTA, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 10% glycerol, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 0.05% Nonidet P-40 (NP-40) and protease inhibitors] containing 150 mM KCl at 4°C. The 0.5 M eluate containing ∼30% of the total protein was dialysed against buffer C150 and applied to a Mono Q HR 5/5 column (Pharmacia). Proteins were eluted with a linear gradient from 0.15 to 0.5 M KCl in buffer C. CHRAC eluted between 0.3 and 0.35 M KCl. Fractions were further fractionated on a 0.5 ml hydroxyapatite (Bio-Rad) column equilibrated with buffer C100 without NP-40. Subsequently, 2 ml washes in 0.01 and 0.1 M potassium phosphate in buffer C were followed by a 20 column-volume gradient from 0.1 to 0.5 M potassium phosphate. Fractions containing CHRAC (0.28–0.32 M potassium phosphate) were concentrated and underwent size exclusion chromatography. Superose 6 column chromatography was performed in buffer C400 containing 20% as before (Varga-Weisz et al., 1997).

Immunoprecipitations

HA-ISWI-tagged embryo extract immunoprecipitation. Twenty microlitres of 12CA5 ascites fluid were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with ∼100 µl of protein A–Sepharose 4B beads (Pharmacia) and 80 µl of incubation buffer (10 mM HEPES–KOH pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 50 mM NaCl). After removal of unbound proteins by three washes with 500 µl of incubation buffer, 25 µl of the resulting immunoaffinity resin were added to 250 µg of embryo extract in a final volume of 125 µl of immunoprecipitation buffer (10 mM HEPES–KOH pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.05% Tween-20, 100 µg/ml PMSF and protease inhibitors). Embryo extracts were prepared as described in the ‘Developmental northern and western blot analysis’ section, from Df(1)w67c2, y P[w+ ISWI+-6HIS-HA]19-4 embryos or from control Df(1)w67c2, y embryos (Deuring et al., 2000). Incubation was performed at 4°C with agitation for 3 h to overnight. Following washing with 60 bead volumes of immunoprecipitation buffer, bound material was eluted by boiling for 5 min in sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS) loading buffer. Bound proteins were analysed by SDS–PAGE and western blotting.

Immunoprecipitation with anti-CHRAC-14 serum. Rabbit anti-CHRAC-14 serum or preimmune serum (1 ml) was incubated overnight at 4°C with ∼100 µl of protein A-coated Sepharose 4B beads (Pharmacia) and unbound protein was removed by three washes with 500 µl of EX500 buffer (500 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EGTA, 10% glycerol). For immunoprecipitation, 30 µl of the immunoaffinity resin were added to 200 µl of Drosophila embryo nuclear extract (15 mg/ml) and 200 µl of EX100 buffer (100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EGTA, 10% glycerol) and incubated with gentle agitation at 4°C for 4 h. After 10 min washes with 500 µl each of EX700, EX500, EX300 and EX100 (700, 500, 300 and 100 mM, respectively, KCl, plus 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EGTA, 10% glycerol), bound material was eluted by boiling for 5 min in SDS loading buffer. Bound proteins were analysed by SDS–PAGE and western blotting.

GST pull-down assay

Protein A–Sepharose 4B beads (75 µl) with immobilized GST, GST–CHRAC-14 or GST–CHRAC-14–CHRAC-16 were used to incubate 2.5 µg of recombinant bacterial ISWI in a final volume of 600 µl in EX80 at 4°C up to overnight. Beads were washed twice with EX80 for 5 min at 4°C, split between three tubes and washed again with EX80, EX150 or EX200. Bound ISWI protein was analysed by SDS–PAGE and western blotting.

Nucleosome sliding assay

Rabbit anti-CHRAC-14 serum or preimmune serum (1 ml) was incubated overnight at 4°C with ∼300 µl of anti-rabbit IgG paramagnetic beads (Dynal) and unbound proteins were removed by three washes with 500 µl of EX80. Immunoaffinity beads (80 µl) were added to 200 µl of Drosophila embryo nuclear extract (15 mg/ml) and 200 µl of EX100. Incubation was at 4°C with gentle agitation for 4 h. After 10 min washes with 500 µl each of EX300 and EX100, bead-bound material was used in the nucleosome sliding assay as described by Längst et al. (1999). Isolated mononucleosomes (60 fmol), centrally positioned on a 248 bp rDNA fragment, were incubated with 5–20 µl of immunoaffinity beads for 60 min at 30°C in 10 µl of EX80 buffer containing 1 mM ATP, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 400 ng BSA/µl and 1 mM DTT. Nucleosome mobility was tested on a 5% acrylamide gel in 0.5× TBE.

Developmental northern and western blot analysis

RNA was isolated and analysed by northern blotting as described previously (Tamkun et al., 1992). To control for even loading, the RNA blot was probed with a radiolabelled fragment from the rp49 gene (O’Connell and Rosbash, 1984). For western blotting, native protein extracts were prepared from wild-type (Oregon R) Drosophila embryos, larvae, pupae and adults as previously described for Drosophila (Papoulas et al., 1998). Equal amounts of total protein (20 µg) were fractionated by SDS–PAGE on a 4–15% gradient gel and transferred to PVDF membranes. Western blots were probed with affinity-purified polyclonal antibodies against CHRAC-14 or ISWI (Tsukiyama et al., 1995). Bound priCHRAC-14 antibody was subsequently visualized using horseradish peroxidase-coupled secondary antibody (Bio-Rad) and Super Signal chemiluminescent reagent (Pierce).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr G.Längst for providing the reagents and expertise for the nucleosome sliding assay. D.F.V.C. specially thanks Mary for inspiration, continuous support and love. He is a fellow of the EMBL International PhD Programme.

References

- Alexiadis V., Varga-Weisz,P.D., Bonte,E., Becker,P.B. and Gruss,C. (1998) In vitro chromatin remodelling by chromatin accessibility complex (CHRAC) at the SV40 origin of DNA replication. EMBO J., 17, 3428–3438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxevanis A.D., Arents,G., Moudrianakis,E.N. and Landsman,D. (1995) A variety of DNA-binding and multimeric proteins contain the histone fold motif. Nucleic Acids Res., 23, 2685–2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellorini M., Lee,D.K., Dantonel,J.C., Zemzoumi,K., Roeder,R.G., Tora,L. and Mantovani,R. (1997) CCAAT binding NF-Y–TBP interactions: NF-YB and NF-YC require short domains adjacent to their histone fold motifs for association with TBP basic residues. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 2174–2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birck C., Poch,O., Romier,C., Ruff,M., Mengus,G., Lavigne,A.C., Davidson,I. and Moras,D. (1998) Human TAF(II)28 and TAF(II)18 interact through a histone fold encoded by atypical evolutionary conserved motifs also found in the SPT3 family. Cell, 94, 239–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burley S.K., Xie,X., Clark,K.L. and Shu,F. (1997) Histone-like transcription factors in eukaryotes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 7, 94–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caretti G., Motta,M.C. and Mantovani,R. (1999) NF-Y associates with H3–H4 tetramers and octamers by multiple mechanisms. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 8591–8603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesnokov I., Gossen,M., Remus,D. and Botchan,M. (1999) Assembly of functionally active Drosophila origin recognition complex from recombinant proteins. Genes Dev., 13, 1289–1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corona D.F.V., Längst,G., Clapier,C.R., Bonte,E.J., Ferrari,S., Tamkun,J.W. and Becker,P.B. (1999) ISWI is an ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling factor. Mol. Cell, 3, 239–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie R.A. (1998) NF-Y is associated with the histone acetyltransferases GCN5 and P/CAF. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 1430–1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuring R. et al. (2000) The ISWI chromatin remodeling protein is required for gene expression and the maintenance of higher order chromatin structure in vivo. Mol. Cell, 5, 355–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Croce L., Koop,R., Venditti,P., Westphal,H.M., Nightingale,K.P., Corona,D.F., Becker,P.B. and Beato,M. (1999) Two-step synergism between the progesterone receptor and the DNA-binding domain of nuclear factor 1 on MMTV minichromosomes. Mol. Cell, 4, 45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen J.A., Sweder,K.S. and Hanawalt,P.C. (1995) Evolution of the SNF2 family of proteins: subfamilies with distinct sequences and functions. Nucleic Acids Res., 14, 2715–2723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elfring L.K., Deuring,R., McCallum,C.M., Peterson,C.L. and Tamkun,J.W. (1994) Identification and characterization of Drosophila relatives of the yeast transcriptional activator SNF2/SWI2. Mol. Cell. Biol., 14, 2225–2234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields S. and Song,O. (1989) A novel genetic system to detect protein–protein interactions. Nature, 340, 245–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangloff Y.G., Werten,S., Romier,C., Carre,L., Poch,O., Moras,D. and Davidson,I. (2000) The human TFIID components TAF(II)135 and TAF(II)20 and the yeast SAGA components ADA1 and TAF(II)68 heterodimerize to form histone-like pairs. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 340–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gdula D.A., Sandaltzopoulos,R., Tsukiyama,T., Ossipow,V. and Wu,C. (1998) Inorganic pyrophosphatase is a component of the Drosophila nucleosome remodeling factor complex. Genes Dev., 12, 3206–3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goppelt A., Stelzer,G., Lottspeich,F. and Meisterernst,M. (1996) A mechanism for repression of class II gene transcription through specific binding of NC2 to TBP-promoter complexes via heterodimeric histone fold domains. EMBO J., 15, 3105–3116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant P.A., Schieltz,D., Pray-Grant,M.G., Steger,D.J., Reese,J.C., Yates,J.R.,III and Workman,J.L. (1998) A subset of TAF(II)s are integral components of the SAGA complex required for nucleosome acetylation and transcriptional stimulation. Cell, 94, 45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guschin D. and Wolffe,A.P. (1999) SWItched-on mobility. Curr. Biol., 9, R742–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamiche A., Sandaltzopoulos,R., Gdula,D.A. and Wu,C. (1999) ATP-dependent histone octamer sliding mediated by the chromatin remodeling complex NURF. Cell, 97, 833–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann A., Chiang,C.M., Oelgeschlager,T., Xie,X., Burley,S.K., Nakatani,Y. and Roeder,R.G. (1996) A histone octamer-like structure within TFIID. Nature, 380, 356–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann A., Oelgeschlager,T. and Roeder,R.G. (1997) Considerations of transcriptional control mechanisms: do TFIID–core promoter complexes recapitulate nucleosome-like functions? Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 8928–8935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt D.F., Yates,J.R.D., Shabanowitz,J., Winston,S. and Hauer,C.R. (1986) Protein sequencing by tandem mass spectrometry. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 83, 6233–6237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imbalzano A.N. (1998) Energy-dependent chromatin remodelers: complex complexes and their components. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr., 8, 225–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inostroza J.A., Mermelstein,F.H., Ha,I., Lane,W.S. and Reinberg,D. (1992) Dr1, a TATA-binding protein-associated phosphoprotein and inhibitor of class II gene transcription. Cell, 70, 477–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T., Bulger,M., Pazin,M.J., Kobayashi,R. and Kadonaga,J.T. (1997) ACF, an ISWI-containing and ATP-utilizing chromatin assembly and remodeling factor. Cell, 90, 145–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T., Levenstein,M.E., Fyodorov,D.V., Kutach,A.K., Kobayashi,R. and Kadonaga,J.T. (1999) ACF consists of two subunits, Acf1 and ISWI, that function cooperatively in the ATP-dependent catalysis of chromatin assembly. Genes Dev., 13, 1529–1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim I.S., Sinha,S., de Crombrugghe,B. and Maity,S.N. (1996) Determination of functional domains in the C subunit of the CCAAT-binding factor (CBF) necessary for formation of a CBF–DNA complex: CBF-B interacts simultaneously with both the CBF-A and CBF-C subunits to form a heterotrimeric CBF molecule. Mol. Cell. Biol., 16, 4003–4013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston R.E. and Narlikar,G.J. (1999) ATP-dependent remodeling and acetylation as regulators of chromatin fluidity. Genes Dev., 13, 2339–2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Längst G., Becker,P.B. and Grummt,I. (1998) TTF-I determines the chromatin architecture of the active rDNA promoter. EMBO J., 17, 3135–3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Längst G., Bonte,E.J., Corona,D.F.V. and Becker,P.B. (1999) Nucleosome movement by CHRAC and ISWI without disruption or trans-displacement of the histone octamer. Cell, 97, 843–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. and Liao,W.S. (1992) Cooperative effects of C/EBP-like and NFκB-like binding sites on rat serum amyloid A1 gene expression in liver cells. Nucleic Acids Res., 20, 4765–4772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X., Meng,X., Morris,C.A. and Keating,M.T. (1998) A novel human gene, WSTF, is deleted in Williams syndrome. Genomics, 54, 241–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luger K., Mäder,A.W., Richmond,R.K., Sargent,D.F. and Richmond,T.J. (1997) Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 Å resolution. Nature, 389, 251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luger K. and Richmond,T.J. (1998) DNA binding within the nucleosome core. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 8, 33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maity S.N. and de Crombrugghe,B. (1998) Role of the CCAAT-binding protein CBF/NF-Y in transcription. Trends Biochem. Sci., 23, 174–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani R. (1998) A survey of 178 NF-Y binding CCAAT boxes. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 1135–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Balbas M.A., Tsukiyama,T., Gdula,D. and Wu,C. (1998) Drosophila NURF-55, a WD repeat protein involved in histone metabolism. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 132–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mermelstein F. et al. (1996) Requirement of a corepressor for Dr1-mediated repression of transcription. Genes Dev., 10, 1033–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuguchi G., Tsukiyama,T., Wisniewski,J. and Wu,C. (1997) Role of nucleosome remodeling factor NURF in transcriptional activation of chromatin. Mol. Cell., 1, 141–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muchardt C. and Yaniv,M. (1999) ATP-dependent chromatin remodelling: SWI/SNF and Co. are on the job. J. Mol. Biol., 293, 187–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell P.O. and Rosbash,M. (1984) Sequence, structure, and codon preference of the Drosophila ribosomal protein 49 gene. Nucleic Acids Res., 12, 5495–5513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogryzko V.V., Kotani,T., Zhang,X., Schlitz,R.L., Howard,T., Yang,X.J., Howard,B.H., Qin,J. and Nakatani,Y. (1998) Histone-like TAFs within the PCAF histone acetylase complex. Cell, 94, 35–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouzounis C.A. and Kyrpides,N.C. (1996) Parallel origins of the nucleosome core and eukaryotic transcription from Archaea. J. Mol. Evol., 42, 234–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papoulas O., Beek,S.J., Moseley,S.L., McCallum,C.M., Sarte,M., Shearn,A. and Tamkun,J.W. (1998) The Drosophila trithorax group proteins BRM, ASH1 and ASH2 are subunits of distinct protein complexes. Development, 125, 3955–3966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poot R.A., Dellaire,G., Hülsmann,B.B., Grimaldi,M.A., Corona, D.F.V., Becker,P.B., Bickmore,W.A. and Varga-Weisz,P.D. (2000) HuCHRAC, a human ISWI chromatin remodelling complex contains hACF1 and two novel histone-fold proteins. EMBO J., 19, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevchenko A., Wilm,M., Vorm,O. and Mann,M. (1996) Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Chem., 68, 850–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha S., Maity,S.N., Lu,J. and de Crombrugghe,B. (1995) Recombinant rat CBF-C, the third subunit of CBF/NFY, allows formation of a protein–DNA complex with CBF-A and CBF-B and with yeast HAP2 and HAP3. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 92, 1624–1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha S., Kim,I.S., Sohn,K.Y., de Crombrugghe,B. and Maity,S.N. (1996) Three classes of mutations in the A subunit of the CCAAT-binding factor CBF delineate functional domains involved in the three-step assembly of the CBF–DNA complex. Mol. Cell. Biol., 16, 328–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struhl K. and Moqtaderi,Z. (1998) The TAFs in the HAT. Cell, 94, 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamkun J.W., Deuring,R., Scott,M.-P., Kissinger,M., Pattatucci,A.M., Kaufmann,T.C. and Kennison,J.A. (1992) brahma: a regulator of Drosophila homeotic genes structurally related to the yeast transcriptional activator SNF2/SWI2. Cell, 68, 561–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travers A. (1999) An engine for nucleosome remodeling. Cell, 96, 311–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukiyama T. and Wu,C. (1995) Purification and properties of an ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling factor. Cell, 83, 1011–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukiyama T., Daniel,C., Tamkun,J. and Wu,C. (1995) ISWI, a member of the SWI2/SNF2 ATPase family, encodes the 140 kD subunit of the nucleosome remodeling factor. Cell, 83, 1021–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga-Weisz P.D. and Becker,P.B. (1998) Chromatin-remodeling factors: machines that regulate? Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 10, 346–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga-Weisz P.D., Wilm,M., Bonte,E., Dumas,K., Mann,M. and Becker,P.B. (1997) Chromatin remodelling factor CHRAC contains the ATPases ISWI and topoisomerase II. Nature, 388, 598–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilm M. and Mann,M. (1996) Analytical properties of the nanoelectrospray ion source. Anal. Chem., 68, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilm M., Shevchenko,A., Houthaeve,T., Breit,S., Schweigerer,L., Fotsis,T. and Mann,M. (1996) Femtomole sequencing of proteins from polyacrylamide gels by nano-electrospray mass spectrometry. Nature, 379, 466–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X., Kokubo,T., Cohen,S.L., Mirza,U.A., Hoffmann,A., Chait,B.T., Roeder,R.G., Nakatani,Y. and Burley,S.K. (1996) Structural similarity between TAFs and the heterotetrameric core of the histone octamer. Nature, 380, 316–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemzoumi K., Frontini,M., Bellorini,M. and Mantovani,R. (1999) NF-Y histone fold α1 helices help impart CCAAT specificity. J. Mol. Biol., 286, 327–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]