Abstract

We have studied the folding during biosynthesis of the lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1) αL subunit using mAb to epitopes that map to seven different regions within the amino acid sequence. The N-terminal portion of αL is predicted to contain a β-propeller domain, consisting of seven β-sheets, and an I domain that is predicted to be inserted between β-sheet 2 and β-sheet 3 of the β-propeller. The I domain of αL folds before association with the β2 subunit, as shown by immunoprecipitation of the unassociated αL subunit by mAbs specific for four different sequence elements within the I domain. By contrast, the β-propeller domain is not folded in unassociated αL after a chase of as long as 12 h after synthesis, but does fold upon association with β2. This is shown with mAbs to regions of αL, that precede and follow the I domain in the primary structure. A mAb that maps near the junction of the C terminus of the I domain with the β-propeller domain suggests that this region is partially folded before subunit association. The results show that the I domain and β-propeller domains fold independently of one another, and suggest that the β-propeller domain bears an interface for association with the β subunit.

Lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1) is a member of the leukocyte integrin or β2 integrin subfamily that is expressed on all leukocytes and is important in adhesive interactions in immune and inflammatory responses (1). LFA-1 consists of αL (CD11a) and β2 (CD18) subunits that are noncovalently associated in a 1:1 complex (2). LFA-1 binds three cell surface ligands that are members of the Ig superfamily, intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1, ICAM-2, and ICAM-3 (1). Interactions with ligands can be transiently up-regulated by cellular activation, apparently both by increased avidity or affinity and changes in association with the cytoskeleton (3–5).

Regions important for ligand binding by integrins have been mapped to the N-terminal portions of integrin α and β subunits (6). One region corresponds to seven repeats of about 60 aa each that have weak sequence homology to one another. The homologies include FG (phenylalanyl-glycyl) and GAP (glycyl-alanyl-prolyl) consensus sequences (7, 8). Seven FG-GAP repeats are found in all integrin α subunits, and the last three or four contain putative Ca2+-binding motifs (9). The FG-GAP repeats have been found to be important for ligand binding particularly for integrins that lack inserted (I) domains (6). Within the third FG-GAP repeat, in 7 of the 16 known integrins in mammals including LFA-1, an I domain is inserted (Fig. 1). In the integrins that contain I domains, the I domain appears to be important for or has been directly implicated in ligand binding (10–19). The three-dimensional structures of the I domains of the leukocyte integrins Mac-1 and LFA-1 were recently solved by x-ray crystallography (20, 21). The I domain folds to a doubly wound α/β structure with a Mg2+ binding site in its crevice. A specific binding site on LFA-1 for ICAM-1 was mapped to residues of the I domain that are on the same face, and surround the Mg2+ binding site (19). This is consistent with the idea that a glutamic acid residue in ICAM-1 that is crucial for binding to LFA-1 (22) could coordinate with the Mg2+.

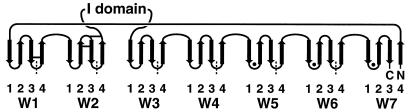

Figure 1.

Folding topology of the predicted LFA-1 α subunit β-propeller domain. β-Strands are arrows, predicted disulfide bonds are horizontal lines, putative Ca2+ ions bound to 1–2 loops are filled circles, and boundaries between FG-GAP repeats are marked with vertical dashes. The Ws are shown upright, with the 1–2 and 3–4 loops on the bottom, and 2–3 loops and 4–1 loops connecting adjacent Ws on the top.

Although previously the FG-GAP repeats have been conceptualized as independent domains, it was recently suggested that they fold cooperatively into a single domain known as a β-propeller (23). In the β-propeller fold, four, six, seven, or eight β-sheets are arranged radially around a central pseudosymmetry axis (24). Each sheet contains four anti-parallel β-strands that form the legs of a W. These sheets are twisted, like the blades of a propeller. The predicted integrin β-propeller contains seven sheets, and hence is a seven-bladed β-propeller (Fig. 1). The sequence threads through the propeller in a circular fashion, so that the N and C termini of the β-propeller sequence are adjacent in the structure, and β-sheet W7 is in between β-sheets W6 and W1. The FG-GAP repeats are predicted to be offset with respect to the Ws, so that the seventh W contains β-strands contributed by the most N-terminal and C-terminal FG-GAP repeats (Fig. 1). The β-propeller is a tightly folded domain, with extensive hydrophobic contacts between each neighboring W (24). The upper surface of the integrin β-propeller is predicted to bind ligand (23). This is consistent with results from mutagenesis studies and with findings that multiple FG-GAP repeats contribute to ligand binding, since all FG-GAP repeats contribute two loops to this surface (reviewed in ref. 23). The Ca2+-binding motifs are predicted to be in close proximity to one another in the loops between β-strands 1 and 2 on the lower surface of the β-propeller. Because removal of Ca2+ activates ligand binding by many integrins and destabilizes association between the α and β subunits in several integrins (4, 5, 25, 26), including LFA-1 (27, 28), the lower surface of the β-propeller may be involved in interactions with the β subunit that regulate ligand binding. The I domain is predicted to be inserted in the connecting loop between β-strand 4 of W2 and β-strand 1 of W3, and to be tethered to the rim of the upper surface of the β-propeller (Fig. 1). Of all structurally characterized β-propeller domains, that of the G protein β subunit is predicted to be most similar to the integrin β-propeller domain. Indeed, these proteins may have evolved from a common ancestor (23). Interestingly, the I domain is structurally homologous to the G protein α subunit (20, 21, 29, 30), and may interact with the β-propeller domain in a manner analogous to that between G protein α and β subunits (23).

We have examined the folding of the β-propeller and I domains during biosynthesis and assembly of the αL/β2 integrin heterodimer to examine whether the I and β-propeller domains fold independently of one another and of the β2 subunit. This information can test the prediction that the β-propeller domain would fold as a unit and provide information on the nature of the association between different domains within leukocyte integrins. Previous studies on leukocyte integrin biosynthesis have shown that the α subunit and β subunit precursors are initially unassociated and have high mannose N-linked carbohydrate, and that processing to complex carbohydrate with an accompanying increase in Mr does not occur until after α and β subunit association (31–35). Thus, transport from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi apparatus is dependent on formation of the αβ complex. In most cell types, the leukocyte integrin β subunit is produced in excess over the α subunits and requires considerably longer to be chased from the precursor to mature form. In leukocyte adhesion deficiency, the β2 integrin subunit is mutated, and the αL subunit precursor is present but does not undergo carbohydrate processing or transport to the surface (34, 35). Most previously characterized mAbs to the LFA-1 α subunit precipitate αL whether or not it is complexed with β; however, at least one mAb, TS2/4, has been shown to only immunoprecipitate the αL/β2 complex (32). Recently, we mapped mAbs to different regions within the α subunit. Multiple subregions are defined within the β-propeller domain and within the LFA-1 I domain (19, 36). Here, we demonstrate by reactivity with mAbs that folding of the β-propeller domain is dependent on association with the β subunit, whereas folding of the I domain is independent of the β-propeller domain and the β subunit.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

mAbs and Cell Lines.

The mouse anti-human CD11a mAbs TS1/22, TS2/4, TS2/6, and TS2/14 and the mouse anti-human CD18 mAb TS1/18 were described (37). The mAbs S6F1 (38), BL5, F8.8, MAY.035 (39), 25–3-1 (40), G-25.2, and CBR LFA-1/1 (41) were obtained through the 5th International Leukocyte Workshop. Antibodies were previously mapped to specific regions of αL (19, 36). The mapping of certain mAbs has been further refined. The P144R substitution abolishes binding of CBR LFA-1/9 and F8.8, and diminishes binding of BL5. Furthermore, these mAbs react with the isolated I domain as shown in BIAcore (Pharmacia) experiments, confirming reactivity within the I domain. The mAb G-25.2 reacts with the h654m and not the m654h chimera, as correctly reported in ref. 36 but not in ref. 19. Immunoprecipitation of the h654m αL/β2 complex confirms assignment of G-25.2 to amino acid residues 443–654 (data not shown).

JY, an Epstein–Barr virus transformed B lymphoblastoid line, was grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% of fetal bovine serum, and 50 μg/ml gentamycin. An Epstein–Barr virus transformed B lymphoblastoid cell line derived from a severely deficient LAD patient was grown in the same medium with 20% fetal bovine serum.

Metabolic Labeling, Immunoprecipitation, and Electrophoresis.

Cultured cells were washed once with cysteine-free RPMI 1640 medium plus 15% dialyzed fetal bovine serum and resuspended to 5 × 106 cells/ml in the same medium. After incubation for 45 min, 500 μCi/ml (1 Ci = 37 GBq) [35S]cysteine (ICN) was added. Cells were pulse labeled for 1 h at 37°C. Half of the cells were harvested, and the remaining cells were chased for 12–16 h with an equal volume of RPMI 1640 medium containing 500 μg/ml cysteine. Labeled cells were washed twice with PBS and resuspended (107 cells/ml) in lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100/150 mM NaCl/20 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.5/1 mM iodoacetamide/1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride/0.24 trypsin inhibitor units/ml of aprotinin/10 μg/ml each of pepstatin A, antipain, and leupeptin) on ice for 30 min. Lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C to remove nuclei and other debris.

Preclearing was with 100 μl of Pansorbin (Calbiochem) and 100 μl of a 1:1 slurry of protein G-Sepharose beads (Pharmacia) per ml of lysate for 2 h at 4°C with gentle agitation. Lysates were again centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min. Equal aliquots of the precleared supernatants (200–400 μl, depending on the experiment) were incubated with antibodies (2 μg of purified IgG or 2 μl of ascites) for 1 h at 4°C in 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes. Nonspecific precipitates were removed by centrifugation for 10 min at 12,000 × g, and supernatants were mixed with 20 μl of a 1:1 slurry of protein G-Sepharose beads at 4°C for 2 h with gentle agitation. Beads were washed three times with lysis buffer and once with lysis buffer without Triton X-100. Beads were mixed with 20 μl of Laemmli SDS sample buffer containing 5% 2-mercaptoethanol and heated for 5 min at 100°C. Eluates were subjected to SDS/7.5% PAGE. Gels were fixed, soaked in EN3HANCE (New England Nuclear) and dried according to manufacturer’s instructions, and exposed to Kodak X-Omat XAR-5 film for 1–7 days at −70°C.

RESULTS

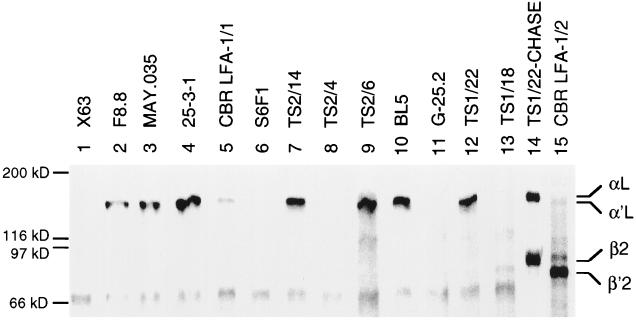

mAbs that had previously been mapped to different subregions of the LFA-1 αL subunit (Fig. 2) were tested for immunoprecipitation of LFA-1 metabolically labeled with [35S]cysteine. Eleven of the mAbs were found to reliably immunoprecipitate LFA-1 from lysates of JY B lymphoblastoid cells that had been pulsed for 1 h with [35S]cysteine and chased for 16 h with unlabeled cysteine. The mAbs immunoprecipitated the mature αL subunit of Mr 175,000 associated with the mature β2 subunit of Mr 95,000 (Fig. 3, lanes 2–11 and 13). The same material was immunoprecipitated by a mAb to the β2 subunit that reacts only with β2 associated with α (Fig. 3, lane 12). The association of the αL and β2 subunits was demonstrated by their coprecipitation. Thus, all 11 anti-αL mAbs could immunoprecipitate αL when it was complexed with β2. Furthermore, all of the mAbs studied here were found to react with a human × mouse hybrid T cell line that expresses the human αL/mouse β2 complex in the absence of human αL/human β2, and not to react with a hybrid line that expresses the mouse αL/human β2 complex (42) (data not shown). This shows that the mAbs recognize species-specific differences in the human αL subunit alone.

Figure 2.

Folding topology and mAb localization for the LFA-1 α subunit I domain (21) and predicted LFA-1 α subunit β-propeller domain (23). β-Strands are arrows, predicted disulfide bonds are horizontal lines, putative Ca2+ ions bound to 1-2 loops are filled circles, and boundaries between FG-GAP repeats are marked with vertical dashes. The regions are shown to which mAbs used in this study map, as determined with human × mouse αL subunit chimeras (19, 36) (see Materials and Methods).

Figure 3.

Immunoprecipitation of mature LFA-1. JY lymphoblastoid cells were labeled for 1 h with [35S]cysteine and chased for 16 h with unlabeled cysteine. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with mouse anti-human LFA-1 antibodies or X63 myeloma IgG as control and subjected to reducing SDS/7.5% PAGE and fluorography. The positions of molecular weight standards, myosin (200 kDa), β-galactosidase (116 kDa), phosphorylase b (97 kDa), and serum albumin (66 kDa), are marked.

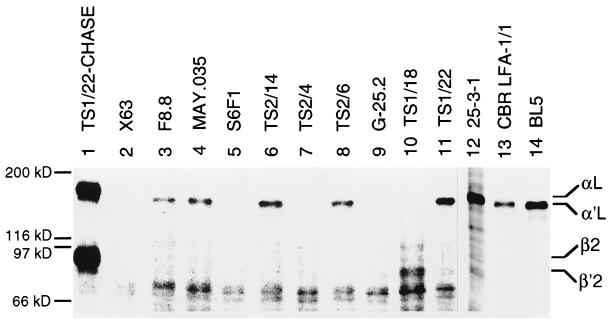

The ability of the antibodies to precipitate the αL precursor (α′L) was tested using lysates of JY cells pulsed for 1 h with [35S]cysteine. At this time point, little αβ association had occurred. Little or no β was coprecipitated by the anti-αL mAb TS1/22 (Fig. 4, lane 12), whereas both α and β were precipitated after the chase (Fig. 4, lane 14). Furthermore, little or no α was precipitated by the anti-β mAb TS1/18 that only precipitates the αβ complex (Fig. 4, lane 13) or by the mAb CBR LFA-1/2 that precipitates both free and complexed β (Fig. 4, lane 15). However, the β′2 precursor was precipitated by CBR LFA-1/2 mAb, and the α′L precursor was precipitated by TS1/22 mAb, showing that precursors were present, but not yet associated. Interestingly, all of the mAbs that map to the I domain (Fig. 2) precipitated the free α′L subunit (Fig. 4, lanes 2–4, 7, 9, 10, and 12). By contrast, two mAbs that mapped to the β-propeller domain failed to precipitate the free α′L subunit (Fig. 4, lanes 6 and 8). Although the S6F1 mAb precipitated less αβ complex than other mAbs (Fig. 3, lane 6), no precipitation of free α′L in the experiment in Fig. 4 was seen even after longer exposure. The mAb G-25.2 that maps either in the β-propeller domain or C-terminal to it also failed to immunoprecipitate free α′L (Fig. 4, lane 11). The mAb CBR LFA-1/1 consistently gave weak precipitation of free α′L (Fig. 4, lane 5) and good precipitation of complexed αL (Fig. 4, lane 5); it mapped to a region overlapping the I and β-propeller domains (Fig. 2).

Figure 4.

Immunoprecipitation of unassociated α′L and β′2 subunit precursors. JY lymphoblastoid cells were pulsed with [35S]cysteine for 1 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with mouse anti-human LFA-1 mAb or X63 myeloma IgG as control, and subjected to reducing SDS/7.5% PAGE and fluorography. As a control, mature LFA-1 was precipitated with TS1/22 from lysates of JY cells that were pulsed for 1 h and chased for 16 h (lane 14).

Differential reactivity of the mAbs with free αL could be because some regions of αL were either slow to fold in the absence of association with β or were completely dependent on association with β for folding. To examine this, a β subunit-deficient B lymphoblastoid cell line from a severe leukocyte adhesion deficiency patient was labeled with [35S]cysteine and chased for 12 h. Lack of αβ complex formation was confirmed with the β subunit mAb TS1/18 (Fig. 5, lane 10). The same results were obtained as with JY cells pulsed for 1 h. mAbs directed to the I domain precipitated αL (Fig. 5, lanes 3, 4, 6, 8, 11, 12, and 14). mAbs to the β-propeller domain (Fig. 5, lanes 5 and 7) and mAb G-25.2 overlapping the end of the β-propeller domain (Fig. 5, lane 9) failed to precipitate αL. mAb CBR LFA-1/1 to the overlap between the I domain and the β-propeller domain gave weaker precipitation (Fig. 5, lane 13) than two other mAbs in the same immunoprecipitation experiment (Fig. 5, lanes 12 and 14). Thus, antibody reactivity correlates with association of αL with β, and not with the length of the chase.

Figure 5.

Immunoprecipitation of unassociated α′L precursor from a leukocyte adhesion deficiency patient cell line. A B lymphoblastoid cell line established from a deficient patient was pulsed for 1 h with [35S]cysteine and chased for 12 h with unlabeled cysteine. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with LFA-1 mAb or X63 myeloma IgG as control and subjected to reducing SDS/7.5% PAGE. Lanes 1–11 and 12–14 are from two separate immunoprecipitation experiments. As a control, lysates from pulse-labeled and chased JY cells were used in lane 1.

DISCUSSION

We have used mAbs as probes for folding during biosynthesis of different regions of the LFA-1 αL subunit. Six mAbs to four different regions within the primary sequence of the I domain reacted with the αL subunit before its association with the β2 subunit, and with the αL/β2 complex. Because mAbs specific for regions of the primary sequence before and following the I domain did not react with the free αL subunit, the I domain folds independently of surrounding αL sequence regions that contribute to the β-propeller domain and independently of the β2 subunit. This is consistent with the finding that the I domain can be expressed as an isolated domain (11, 16, 20, 21). It also is consistent with the notion that in native integrin αβ complexes, the I domain and β-propeller domain might move relative to one another, for example in regulation of ligand binding (23).

The seven FG-GAP repeats of integrins have been proposed based on multiple lines of evidence to fold into a seven-bladed β-propeller domain (23). The I domain is predicted to be inserted into the connecting loop between W2 and W3, on the rim of the upper surface of the β-propeller (Fig. 2). Two mAbs that map to a region of the β-propeller domain primary sequence N terminal to the I domain failed to react with the αL subunit before its association with the β2 subunit, but reacted with the αL/β2 complex. The same result was obtained with G-25.2 mAb that localizes to a region C terminal of the I domain. Of the 212 aa residues to which this mAb maps, 159 are located in the β-propeller domain. The same three mAbs also failed to react with αL in β2 subunit-deficient patient cell lines after a 12-h chase, confirming dependence on association with β, and suggesting that even if an extended time period for folding is allowed, it does not occur in the absence of β. Thus at least one, and possibly two, different regions of the β-propeller domain require β subunit association for proper folding. Similar to these results, the G protein β subunit β-propeller does not fold in absence of association with the G protein γ subunit (43).

The mAb CBR LFA-1/1 recognizes regions of overlap between neighboring domains. It maps to a region including the last amino acid of the C-terminal I domain α-helix (21), a linker region between the I domain and the predicted beginning of β-propeller β-sheet W3, and the first 3/4 of W3. The only differences between the human and mouse sequences, respectively, in this region are 304 KK/RR at the end of the C-terminal α-helix, 313 SK/NR in the linker, and 356 KA/RE in the predicted loop between strands 3 and 4 in W3 of the β-propeller. The mAb CBR LFA-1/1 consistently reacted less well with the free αL subunit than mAbs to the I domain; it will be of interest to localize its epitope more precisely to determine whether its intermediate reactivity with αL reflects recognition of a boundary region between the I and β-propeller domains.

From this and other papers, a picture is beginning to emerge of how specific domains in integrin α and β subunits may associate. In another study, we have found that folding of the conserved domain of the integrin β2 subunit is dependent on association with the αL subunit (44). However, folding of the region N terminal to the conserved domain and two subregions that are C terminal to the conserved domain is not dependent on αL association. Thus far, we have not identified mAbs that map completely within the region C terminal to the β-propeller domain in αL, and do not know whether this region is folded in the absence of β. However, it has been shown for the αIIb/β3 integrin that a Mr 55,000 fragment of αIIb, corresponding to approximately the N-terminal 490 residues, together with a fragment corresponding to most of the extracellular domain of β3, retains native conformation and ligand binding activity (45). The β-propeller domain of αIIb is predicted to be 452-aa residues (23) and to account for most of the Mr 55,000 fragment. Together, these data suggest that the α subunit β-propeller domain may associate with the β-subunit conserved domain and account for the mutual dependence of these regions for αβ association for folding. It is interesting that at least for several integrins, divalent cations stabilize αβ association. Removal of Ca2+ results in dissociation of α and β in detergent-solubilized αIIb/β3 (25) and makes α and β susceptible to dissociation by high pH in αL/β2 (28). The Ca2+-binding motifs in integrin α subunits are predicted to be close to one another on the lower surface of the β-propellers, and therefore this lower surface may associate with the β subunit conserved domain. Chelation of Ca2+ can also result in activation of integrins, suggesting that this interface may also be important in integrin regulation (26, 27).

Our results provide a rough outline of how domains within integrins may associate. Although the I domain is inserted within the β-propeller domain, these domains are conformationally independent. The conformation of the β-propeller domain is dependent on association with the β subunit, and since the conformation of the conserved domain within the β subunit is dependent on association with the α subunit, the β-propeller and conserved domains may associate. This work further advances understanding of the structure and function of integrins, and of identification of subregions that may lend themselves to definitive three-dimensional structural characterization.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant CA31798.

ABBREVIATIONS

- LFA

lymphocyte function-associated antigen

- ICAM

intercellular adhesion molecule

References

- 1.Springer T A. Cell. 1994;76:301–314. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kürzinger K, Springer T A. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:12412–12418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dustin M L, Springer T A. Nature (London) 1989;341:619–624. doi: 10.1038/341619a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diamond M S, Springer T A. Curr Biol. 1994;4:506–517. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00111-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ginsberg M H. Biochem Soc Trans. 1995;23:439–446. doi: 10.1042/bst0230439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loftus J C, Smith J W, Ginsberg M H. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:25235–25238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corbi A L, Miller L J, O’Connor K, Larson R S, Springer T A. EMBO J. 1987;6:4023–4028. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02746.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larson R S, Corbi A L, Berman L, Springer T A. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:703–712. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.2.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuckwell D S, Brass A, Humphries M J. Biochem J. 1992;285:325–331. doi: 10.1042/bj2850325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diamond M S, Garcia-Aguilar J, Bickford J K, Corbi A L, Springer T A. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:1031–1043. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.4.1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michishita M, Videm V, Arnaout M A. Cell. 1993;72:857–867. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90575-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muchowski P J, Zhang L, Chang E R, Soule H R, Plow E F, Moyle M. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26419–26423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rieu P, Ueda T, Haruta I, Sharma C P, Arnaout M A. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:2081–2091. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou L, Lee D H S, Plescia J, Lau C Y, Altieri D C. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:17075–17079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Champe M, McIntyre B W, Berman P W. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1388–1394. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.3.1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landis R C, Bennett R I, Hogg N. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:1519–1527. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.6.1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kern A, Briesewitz R, Bank I, Marcantonio E E. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:22811–22816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamata T, Takada Y. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26006–26010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang C, Springer T A. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:19008–19016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.32.19008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee J-O, Rieu P, Arnaout M A, Liddington R. Cell. 1995;80:631–638. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90517-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qu A, Leahy D J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10277–10281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Staunton D E, Dustin M L, Erickson H P, Springer T A. Cell. 1990;61:243–254. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90805-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Springer T A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;94:65–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murzin A G. Proteins. 1992;14:191–201. doi: 10.1002/prot.340140206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jennings L K, Phillips D R. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:10458–10466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ginsberg M H, Lightsey A, Kunicki T J, Kaufmann A, Marguerie G, Plow E F. J Clin Invest. 1986;78:1103–1111. doi: 10.1172/JCI112667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dransfield I, Cabañas C, Craig A, Hogg N. J Cell Biol. 1992;116:219–226. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.1.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dustin M L, Carpen O, Springer T A. J Immunol. 1992;148:2654–2663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edwards Y J K, Perkins S J. FEBS Lett. 1995;358:283–286. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01447-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee J-O, Bankston L A, Arnaout M A, Liddington R C. Structure (London) 1995;3:1333–1340. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00271-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ho M-K, Springer T A. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:2766–2769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanchez-Madrid F, Nagy J, Robbins E, Simon P, Springer T A. J Exp Med. 1983;158:1785–1803. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.6.1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sastre L, Kishimoto T K, Gee C, Roberts T, Springer T A. J Immunol. 1986;137:1060–1065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Springer T A, Thompson W S, Miller L J, Schmalstieg F C, Anderson D C. J Exp Med. 1984;160:1901–1918. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.6.1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kishimoto T K, Hollander N, Roberts T M, Anderson D C, Springer T A. Cell. 1987;50:193–202. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90215-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang C, Springer T A. In: Leucocyte Typing V: White Cell Differentiation Antigens. Schlossman S F, Boumsell L, Gilks W, Harlan J, Kishimoto T, Morimoto T, Ritz J, Shaw S, Silverstein R, Springer T, Tedder T, Todd R, editors. New York: Oxford Univ. Press; 1995. pp. 1595–1597. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanchez-Madrid F, Krensky A M, Ware C F, Robbins E, Strominger J L, Burakoff S J, Springer T A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:7489–7493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.23.7489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morimoto C, Rudd C E, Letvin N L, Schlossman S F. Nature (London) 1987;330:479–482. doi: 10.1038/330479a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohashi Y, Tsuchiya S, Fujie H, Minegishi M, Konno T. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1992;167:297–299. doi: 10.1620/tjem.167.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fischer A, Blanche S, Veber F, Delaage M, Mawas C, Griscelli C, Le Deist F, Lopez M, Olive D, Janossy G. Lancet. 1986;ii:1058–1061. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)90465-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petruzzelli L, Maduzia L, Springer T. J Immunol. 1995;155:854–866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marlin S D, Morton C C, Anderson D C, Springer T A. J Exp Med. 1986;164:855–867. doi: 10.1084/jem.164.3.855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garcia-Higuera I, Fenoglio J, Li Y, Lewis C, Panchenko M P, Reiner O, Smith T F, Neer E J. Biochemistry. 1996;35:13985–13994. doi: 10.1021/bi9612879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang C, Lu C, Springer T A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3156–3161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lam S C-T. J Biol Chem. 1995;267:5649–5655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]