Abstract

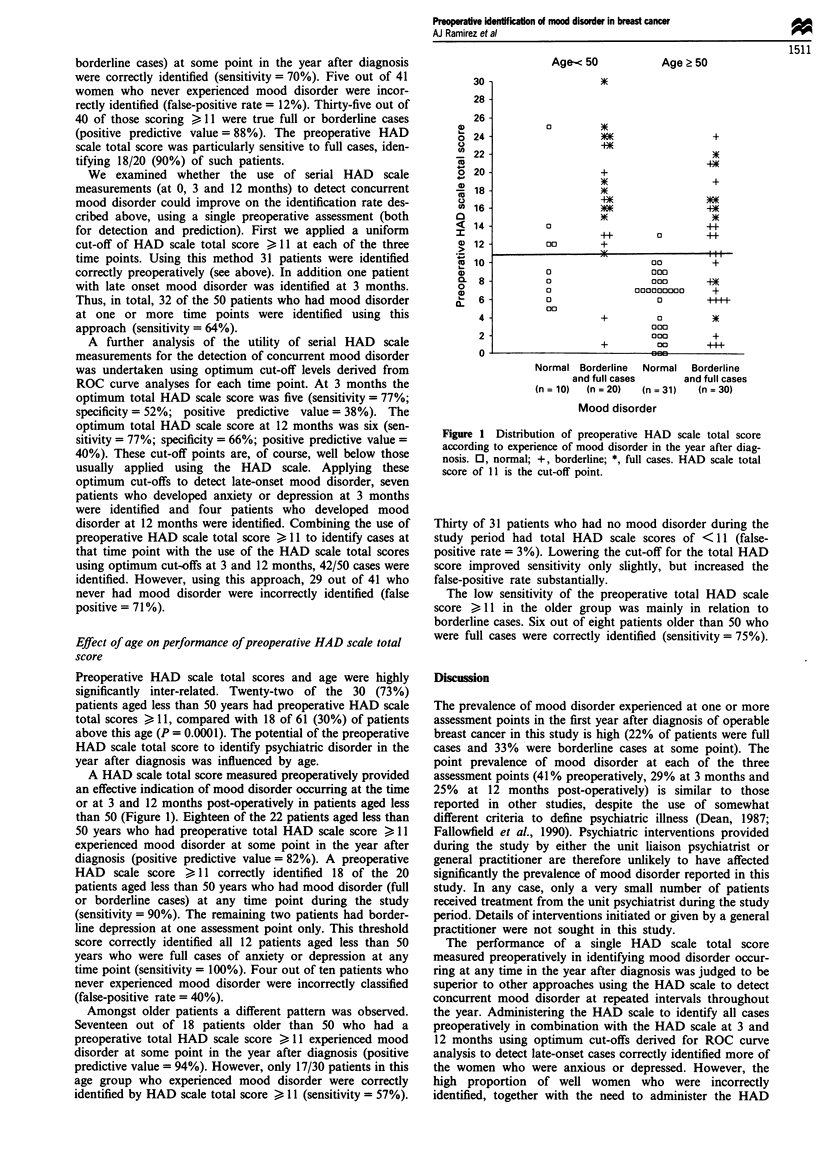

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale, a self-report questionnaire, was tested as a method of identifying mood disorder among patients with operable breast cancer during the year after diagnosis. In a cohort of 91 patients anxiety and depression were assessed preoperatively, and at 3 and 12 months post-operatively, using a standardised psychiatric interview and diagnostic rating criteria. The patients also completed the HAD scale at each assessment. Fifty out of 91 (55%) patients were full or borderline cases of depression and/or anxiety at one or more assessment points. Using a receiver operator characteristic curve analysis, the optimum threshold for the preoperative HAD scale total score to identify psychiatric disorder either preoperatively or at 3 and 12 months post-operatively was 11. With this threshold 70% of both full and borderline cases occurring at any of the assessment points were correctly identified. The false-positive rate was 12%. This approach was particularly sensitive to full cases, correctly identifying 90% of them. The potential for the preoperative HAD scale total score to identify mood disorder in the year after diagnosis was influenced by age. Among women aged less than 50 years, a preoperative HAD scale total score > or = 11 provided a highly sensitive indicator of mood disorder (full and borderline cases) at any time in the year after diagnosis (sensitivity = 90%). The false-positive rate was 40%. Among women older than 50 who experienced a mood disorder, only 57% were correctly identified by a HAD scale total score of > or = 11 (sensitivity = 57%). However, the false-positive rate among older women was low (3%). This simple preoperative screening approach can be used to identify patients who have or are at high risk of developing severe mood disorder in the year after diagnosis. The HAD scale is also sensitive to the detection of borderline mood disorder in patients under the age of 50. It is a specific screening tool among patients over 50, but is not sensitive to the detection of borderline mood disorder in this age group.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Costa D., Mogos I., Toma T. Efficacy and safety of mianserin in the treatment of depression of women with cancer. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1985;320:85–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1985.tb08081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean C. Psychiatric morbidity following mastectomy: preoperative predictors and types of illness. J Psychosom Res. 1987;31(3):385–392. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(87)90059-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallowfield L. J., Hall A., Maguire G. P., Baum M. Psychological outcomes of different treatment policies in women with early breast cancer outside a clinical trial. BMJ. 1990 Sep 22;301(6752):575–580. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6752.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay-Jones R., Brown G. W., Duncan-Jones P., Harris T., Murphy E., Prudo R. Depression and anxiety in the community: replicating the diagnosis of a case. Psychol Med. 1980 Aug;10(3):445–454. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700047334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer S., Moorey S., Baruch J. D., Watson M., Robertson B. M., Mason A., Rowden L., Law M. G., Bliss J. M. Adjuvant psychological therapy for patients with cancer: a prospective randomised trial. BMJ. 1992 Mar 14;304(6828):675–680. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6828.675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood P., Howell A., Maguire P. Screening for psychiatric morbidity in patients with advanced breast cancer: validation of two self-report questionnaires. Br J Cancer. 1991 Aug;64(2):353–356. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1991.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibbotson T., Maguire P., Selby P., Priestman T., Wallace L. Screening for anxiety and depression in cancer patients: the effects of disease and treatment. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30A(1):37–40. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(05)80015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy J. M., Berwick D. M., Weinstein M. C., Borus J. F., Budman S. H., Klerman G. L. Performance of screening and diagnostic tests. Application of receiver operating characteristic analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987 Jun;44(6):550–555. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180068011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razavi D., Delvaux N., Bredart A., Paesmans M., Debusscher L., Bron D., Stryckmans P. Screening for psychiatric disorders in a lymphoma out-patient population. Eur J Cancer. 1992;28A(11):1869–1872. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(92)90025-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razavi D., Delvaux N., Farvacques C., Robaye E. Screening for adjustment disorders and major depressive disorders in cancer in-patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1990 Jan;156:79–83. doi: 10.1192/bjp.156.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snaith P. Psychological treatments for patients with cancer. BMJ. 1992 Jun 13;304(6841):1569–1569. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6841.1569-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond A. S., Snaith R. P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983 Jun;67(6):361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]