Abstract

Transferrin (Tf) conjugates of CRM107 are currently being tested in clinical trials for treatment of malignant gliomas. However, the rapid cellular recycling of Tf limits its efficiency as a drug carrier. We have developed a mathematical model of the Tf/TfR trafficking cycle and have identified the Tf iron release rate as a previously unreported factor governing the degree of Tf cellular association. The release of iron from Tf is inhibited by replacing the synergistic carbonate anion with oxalate. Trafficking patterns for oxalate Tf and native Tf are compared by measuring their cellular association with HeLa cells. The amount of Tf associated with the cells is an average of 51% greater for oxalate Tf than for native Tf over a two hour period at Tf concentrations of 0.1 nM and 1 nM. Importantly, diphtheria toxin (DT) conjugates of oxalate Tf are more cytotoxic against HeLa cells than conjugates of native Tf. Conjugate IC50 values were determined to be 0.06 nM for the oxalate Tf conjugate vs. 0.22 nM for the native Tf conjugate. Thus, we show that inhibition of Tf iron release improves the efficacy of Tf as a drug carrier through increased association with cells expressing TfR.

Keywords: Transferrin, Diphtheria toxin, Drug carrier, Trafficking, Targeted cancer therapy

1. Introduction

The serum iron transport protein transferrin (Tf) has been investigated as a potential drug carrier to allow specific targeting to cancer cells, since the transferrin receptor (TfR) is overexpressed in a broad range of cancers [1, 2]. Specific targeting of drugs to cancer cells may help alleviate nonspecific toxicity associated with chemotherapy and radiation treatments [3, 4]. Tf conjugates of cytotoxins including methotrexate (MTX), artemisinin, and diphtheria toxin (DT) have been reported, as well as Tf conjugates with novel payloads such as liposomally encapsulated drugs and siRNA [5–12]. The use of Tf conjugates for cancer therapy is currently being assessed in clinical trials. For example, Tf conjugates of CRM107, a point mutant of DT with reduced nonspecific binding, are being studied as treatment for malignant gliomas. Results of a Phase II trial indicated complete and partial tumor response in 35% of patients treated with the Tf-CRM107 conjugate [13].

In addition to Tf, other ligands which bind TfR have been used to target therapeutics to cancer cells, including TfR monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and Tf oligomers [5, 14]. Work from the Murphy laboratory has explored the principles governing the effectiveness of different cytotoxin conjugates targeting TfR [14–16]. Using in vitro cell experiments and mathematical modeling, Murphy showed that the cellular trafficking of the ligand is an important factor. Specifically, it was demonstrated that the duration of cellular trafficking is correlated with the effectiveness of drug delivery. For example, the trafficking of TfR mAbs is somewhat different than Tf, because the mAbs are more prone to intracellular degradation than to being recycled to the cell surface. This increases the cellular association of TfR mAbs relative to Tf, and as a result, gelonin conjugates of TfR mAbs show increased cytotoxicity over gelonin conjugates of Tf [14]. Similarly, oligomerization of Tf increases intracellular degradation in comparison to monomeric Tf. Consequently, MTX conjugates of Tf oligomers show greater cytotoxicity than MTX conjugates of monomeric Tf [5].

Therefore, the effectiveness of cytotoxin conjugates may be enhanced by identifying ligands for TfR which exhibit an increased degree of cellular association. One strategy is to engineer Tf in order to modify its normal trafficking behavior such that its cellular association is increased. The general principle of modifying cellular trafficking behavior to achieve a beneficial effect has been successfully applied to other systems. For example, a mutated version of granulocyte colony stimulating factor (GCSF) which favors the cellular recycling pathway results in a significantly extended GCSF half-life [17]. In addition, IgG antibodies with mutated Fc regions resulting in greater binding affinities for the FcRn receptor in the endosome show an increase in cellular recycling, leading to longer half-lives in vivo [18].

In the current study, we have applied a mathematical model of Tf/TfR cellular trafficking in order to alter the trafficking pathway of Tf to increase its cellular association. We identify the release rate of iron from Tf as a previously unidentified factor influencing the degree of cellular association. We then demonstrate that Tf ligands modified to inhibit iron release associate with HeLa cells to a greater extent when compared to native Tf. Finally, we show that DT conjugates of iron release modified Tf ligands are significantly more cytotoxic than DT conjugates of native Tf in an in vitro cell-killing assay.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Mathematical model of Tf/TfR trafficking

A previously reported Tf/TfR trafficking model was integrated with a model of endosomal sorting [19, 20]. When necessary, additional terms were added to enable the trafficking simulation of Tf ligands with modified properties. For example, to enable the simulation of an iron-free Tf (apo-Tf) ligand with an increased association rate for TfR, a term describing the association of apo-Tf for TfR was added to the species balance of the apo-Tf/TfR surface complex. This was not accounted for in the original model, since the apo-form of native Tf does not bind TfR. A full list of model equations and parameters is provided in the Appendix.

Model equations were solved with initial conditions of zero for all species except the concentration of iron-loaded diferric Tf, or holo-Tf, in the media (1 nM) and the number of transferrin receptors on the cell surface (5.4 × 105 receptors) [15]. The length of the simulations was 50 h. To quantify cellular association of Tf ligands, the area under the curve (AUC) of internalized Tf vs. time was calculated.

2.2. Cell culture

HeLa cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were seeded on 35 mm dishes (Becton Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ) in MEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 2.2 g/L sodium bicarbonate, 10% FBS (Hyclone, Logan, UT), 1% sodium pyruvate (Invitrogen), 100 units/mL penicillin (Invitrogen), and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen) at a pH of 7.4. Cells were incubated overnight at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 to a final density of 4 × 105 cells/cm2. All reagents and materials were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise noted.

2.3. Radiolabeling of Tf ligands

Holo-Tf proteins were iodinated with Na125I from MP Biomedicals (Irvine, CA) using IODO-BEADS from Pierce Biotechnology (Rockford, IL). Radiolabeled Tf was purified using a Sephadex G-10 column with bovine serum albumin present to block non-specific binding.

2.4. Cellular trafficking of Tf ligands

Trafficking experiments were performed in triplicate. After aspirating the seeding medium, incubation medium containing varying concentrations of radiolabeled holo-Tf was added to each dish. This medium was comprised of MEM supplemented with 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 containing 1% sodium pyruvate, 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. After 5, 15, 30, 60, 90, or 120 min, the incubation medium was aspirated and the dishes were washed five times with ice-cold WHIPS (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 containing 1 mg/mL PVP, 130 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 0.5 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM CaCl2) to remove non-specifically bound Tf. Ice-cold acid strip solution (1 mL of 50 mM glycine-HCl, pH 3.0 containing 100 mM NaCl, 1 mg/mL polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), and 2 M urea) was then added to each dish. Dishes were placed on ice for 8 min and then washed again with an additional mL of the acid strip solution. Following the removal of the specifically bound Tf on the cell surface by the acid strip washes, NaOH (1 mL of 1 M) was added to the dishes for 30 min to solubilize the cells. After addition of another mL of NaOH, the two basic washes were collected and counted to determine the amount of internalized Tf.

2.5. Conjugation of Tf with diphtheria toxin

DT conjugates of holo-Tf were made using 2-iminothiolane and sulfo-SMCC (Pierce Biotechnology) as crosslinkers. To thiolate DT, 6.4 μL of an iminothiolane-HCl solution (prepared by dissolving 0.5 mg of iminothiolane-HCl in 800 μL of the borate buffer) was added to 0.3 mg of DT dissolved in 60 μL of borate buffer (0.1 M sodium borate, pH 8 containing 1 μM EDTA, 0.15 M NaCl). After 90 minutes at room temperature, the thiolated DT was separated from free iminothiolane by size exclusion chromatography using small spin columns (Zeba Desalt Spin Column, Pierce Biotechnology). While DT was being thiolated, Tf was reacted with sulfo-SMCC by first dissolving 0.5 mg of sulfo-SMCC in 20 μL of DMSO and then adding that solution to 80 μL of borate buffer. Tf (16 mg) was dissolved in 2 mL of borate buffer and 36 μL of the SMCC solution was added. After 90 minutes at room temperature, the modified Tf-SMCC compound was then separated from free sulfo-SMCC by size exclusion chromatography using the spin columns. The two modified protein solutions were diluted, incubated together overnight at 4°C, and reduced in volume using centrifugal concentrators (Centriprep YM-10, Millipore, Billerica, MA). The DT conjugates with a 1:1 Tf:DT ratio in the concentrated solution were then purified by HPLC (AKTA FPLC Chromatographic System, GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Piscataway, NJ) using a HiPrep 16/60 Sephacryl S-200 HR size exclusion column (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences); the identity of each peak was confirmed by SDS-PAGE. The concentration of the 1:1 Tf:DT conjugates was quantified using the absorbance of holo-Tf at 465 nm with a measured extinction coefficient of 0.0506 mL mg−1 cm−1.

2.6. Cytotoxicity assay

The MTT cell proliferation assay was used to determine cell survival according to instructions supplied by the manufacturer (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA). Briefly, HeLa cells (2 × 104 cells) were seeded into each well of a 24-well tissue culture plate with four wells for each condition. After incubating the cells overnight, the seeding medium was aspirated, and the cells were washed with PBS and incubated for 48 hours with 450 μL of fresh seeding medium containing varying concentrations of DT conjugates. Reagent AB (40 μL of 5 mg/mL MTT in PBS) was then added to each well for 4 hours, followed by the addition of 450 μL of Reagent C (isopropanol with 0.04 M HCl) for color development. Visible light absorbance of each well was measured at 570 nm and 630 nm with a plate reader. The survival of cells relative to the control (cells incubated with media containing no DT conjugates) was calculated by taking the ratio of the (A570 – A630) values. Cytotoxicity experiments were performed four times.

3. Results

3.1. Mathematical model identifies Tf iron release as a factor governing cellular association

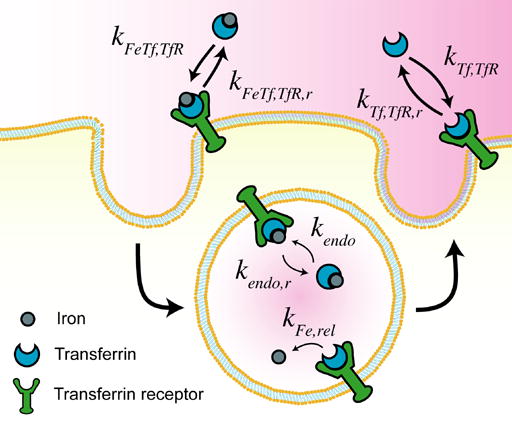

The transport of Tf into cells has been extremely well characterized and serves as a model for receptor mediated endocytosis [21] (Fig. 1). To determine how Tf can be modified to increase cellular association, we developed a mathematical model of the Tf/TfR trafficking pathway to assess how changes in properties of Tf might affect its trafficking through cells. We considered seven different properties associated with ligand/receptor and ligand/metal interactions that could in principle be modified (Table 1). The specific properties in the context of the Tf/TfR trafficking cycle are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the Tf/TfR trafficking pathway.

Table 1.

List of potentially modifiable Tf molecular properties

| Rate | Definition | Native Value | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| kFeTf,TfR a | Association rate of holo-Tf for TfR | 4 ± 1 × 107 M−1 min−1 | [15] |

| kFeTf,TfR,r a | Dissociation rate of holo-Tf from TfR | 1.3 ± 0.5 min−1 | [15] |

| kTf,TfR | Association rate of apo-Tf for TfR | 0.0 M−1 min−1 | [23] |

| kTf,TfR,r | Dissociation rate of apo-Tf from TfR | 2.6 min−1 | [19] |

| kendo b | Endosomal association rate of Tf for TfR | 4.4 ± 0.4 × 107 M−1 min−1 | [23] |

| kendo,r b | Endosomal dissociation rate of Tf from TfR | 0.056 ± 0.012 min−1 | [23] |

| kFe,rel | Tf iron release rate | 1.0 × 102 min−1 | Est. |

Range reported is the 95% confidence interval.

Range reported is the mean and standard deviation.

Fig. 2.

Illustration of Tf properties varied in the model.

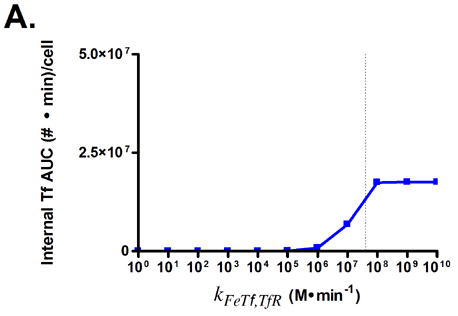

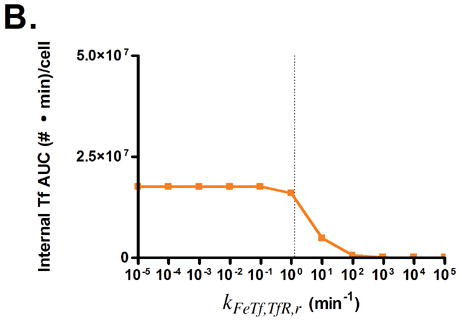

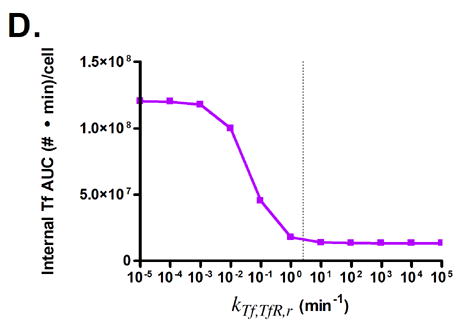

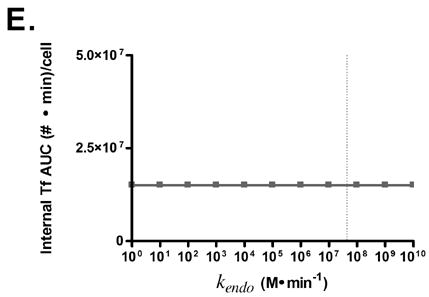

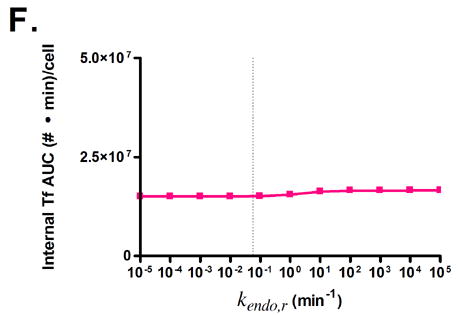

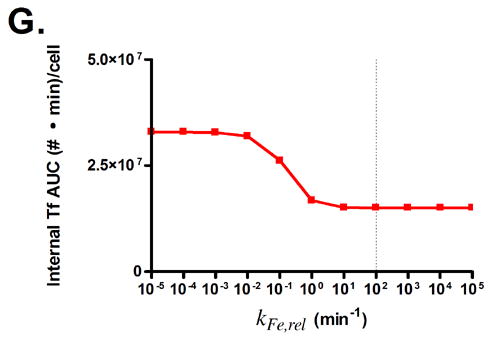

The effects of modifying these properties on the degree of cellular association were investigated by ranging the value of each property over several orders of magnitude (Fig. 3). Cellular association is quantified by taking the area under the curve (AUC) of the internalized Tf values generated by model simulations, such that higher AUC values correspond to increased cellular association.

Fig. 3.

Predicted responses in cellular association to changes in Tf parameters. Dashed lines indicate native Tf values for each property. Note change in scale for plots 3C and 3D.

Surprisingly, only minor increases in cellular association are predicted for increasing the affinity of holo-Tf for TfR (Figs. 3A and B). This is due to the fast rate of iron release (2–3 min) from Tf upon internalization into the endosome, which converts holo-Tf into apo-Tf [22]. This rapid conversion to apo-Tf from holo-Tf counteracts the expected increase in cellular association from increasing the affinity of holo-Tf for TfR, since apo-Tf has undetectable binding to TfR at neutral pH and is thus quickly released from TfR upon recycling back to the cell surface [23]. This phenomenon accounts for the large increases in cellular association predicted when the binding affinity of apo-Tf for TfR is increased (Figs. 3C and D).

Variation of endosomal binding affinity for TfR was not predicted to lead to a significant change in cellular association. In the endosomal sorting model used, dissociation of Tf from TfR in the endosome raises the likelihood of Tf being routed to the lysosome and degraded. This increases the cellular association of Tf slightly, since the rate constants characterizing the length of time spent in the degradation pathway are lower than those for the recycling pathway. Nevertheless, this increase in cellular association is minimal compared to the predicted increases seen in Figs. 3C, D, and G.

Fig. 3G shows that lowering the rate of iron release from Tf is predicted to lead to an increase in Tf cellular association. In this instance, the lowered iron release rate allows Tf to remain as holo-Tf upon being recycled, thus retaining its affinity for TfR.

3.2. Lowering the Tf iron release rate through replacement of carbonate with oxalate

To test the prediction of the model, we generated a version of Tf in which iron release is inhibited. This strategy seemed preferable over attempting to increase the affinity of apo-Tf for TfR, as increasing protein affinity is very challenging [24] whereas the literature contains numerous examples of successful efforts to slow or inhibit iron release from Tf. We chose to replace the synergistic carbonate anion with oxalate, which greatly reduces the iron release rate of iron from Tf without significantly affecting its binding affinity for TfR [25]. A summary of the iron release rates for native Tf and oxalate Tf [19] is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Iron release rates of native Tf vs. oxalate Tf in the presence of 12 mM Tiron (pH 7.4) or 4 mM EDTA (pH 5.6) [25].

| Native Tf (min−1) | Oxalate Tf (min−1) | |

|---|---|---|

| Tf (pH 7.4, N-lobe) | 0.044 ± 0.002 | 0.0005 ± 0.00003 |

| Tf (pH 7.4, C-lobe) | 0.037 ± 0.002 | 0.0032 ± 0.0002 |

| Tf (pH 5.6, N-lobe) | 16.8 ± 1.3 | 0.192 ± 0.008 |

| Tf (pH 5.6, C-lobe) | 0.139 ± 0.006 | 0.0083 ± 0.0010 |

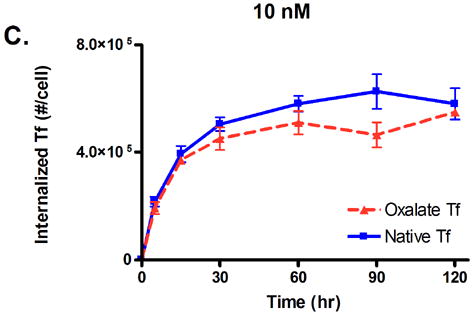

3.3. Trafficking of Tf in HeLa cells shows increased cellular association of oxalate Tf compared to native Tf

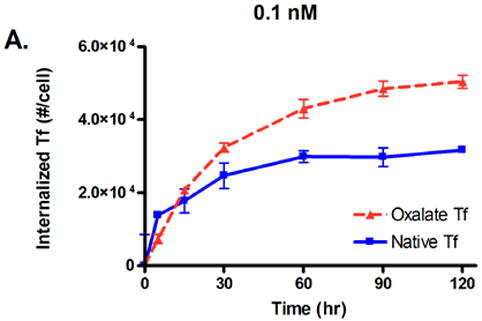

To test our prediction that a lowered iron release rate would increase the cellular association of Tf, we conducted in vitro cell trafficking experiments with HeLa cells. Native Tf and oxalate Tf were radiolabeled with iodine-125 and incubated with HeLa cells for two hours, and the amount of internalized Tf as a function of concentration and time was monitored (Fig. 4). The results show that HeLa cells internalize a significantly greater amount of oxalate Tf compared to native Tf at concentrations of 0.1 nM and 1 nM. At the end of the two hour period, at a concentration of 0.1 nM, the level of native Tf had reached 3.2 × 104 internalized Tf molecules per cell, compared to 5.0 × 104 internalized Tf molecules per cell for oxalate Tf (Fig. 4A). Taking the AUC for each curve, we obtain values of 3.1 × 106 (#·min)/cell for native Tf and 4.5 × 106 (#·min)/cell for oxalate Tf, an increase of 45%. Similarly, at 1 nM, native Tf had reached 2.4 × 105 internalized Tf molecules per cell compared to 4.1 × 105 internalized Tf molecules per cell for oxalate Tf (Fig. 4B). The AUC values of each curve are 2.3 × 107 (#·min)/cell for native Tf vs. 3.6 × 107 (#·min)/cell for oxalate Tf, an increase of 57%. At 10 nM, the difference in cellular association between oxalate Tf and native Tf diminishes because the receptors become saturated (Fig. 4C). These results support the hypothesis that inhibition of iron release from Tf can increase its cellular association.

Fig. 4.

Internalized Tf/cell for oxalate Tf vs. native Tf at concentrations of 0.1, 1, and 10 nM. Error bars represent the standard deviation from an average of three measurements.

3.4. Diphtheria toxin conjugates of oxalate Tf are more cytotoxic against HeLa cells than native Tf conjugates

To test whether an increase in cellular association would translate to increased Tf drug carrier efficacy, we produced DT conjugates with oxalate Tf and native Tf. These conjugates were administered to cultured HeLa cells over a range of DT concentrations (10−3 nM to 10 nM), and using the MTT assay, the % inhibition of cellular growth was assessed after 48 hours. DT conjugates of oxalate Tf are significantly more cytotoxic than DT conjugates of native Tf (Fig. 5). IC50 values, the concentrations at which 50% inhibition of cellular growth was achieved, are 0.22 nM for native Tf compared to 0.06 nM for oxalate Tf.

Fig. 5.

Cytotoxicity comparison between DT conjugates of oxalate Tf vs. native Tf. Error bars represent standard error from an average of four experiments.

4. Discussion

Although Tf has been extensively investigated as a potential delivery agent for cancer therapeutics, the rapid recycling of Tf through the endocytic TfR pathway may significantly limit its efficiency as a drug carrier [5]. Tf is recycled back into the bloodstream as apo-Tf, which has a non-detectable binding affinity for TfR [23]. Rebinding of iron by Tf can be a variable and inefficient process, and therefore in models of Tf trafficking, recycled Tf is often assumed to be lost [15, 19]. Thus, the window of drug delivery for a Tf conjugate may well be limited to one passage through a cell. Furthermore, studies suggest that the translocation of drug from the conjugate into the cytosol is frequently the rate-limiting step of the overall drug delivery process [14]. For example, it has been estimated that in the case of Tf conjugates of the gelonin cytotoxin that for every ten million conjugates that are recycled, only one molecule of gelonin is actually delivered into the cell. Therefore, it appears unlikely that any given gelonin conjugate trafficking once through the cell will deliver its drug and achieve its intended purpose.

To address this inefficiency, alternate TfR ligands with different trafficking properties than those of Tf have been investigated, such as TfR mAbs and Tf oligomers [5, 14]. Because these ligands continue to utilize the TfR pathway, they maintain specificity towards cancer cells which overexpress TfR. However, unlike Tf, these ligands appear to favor intracellular degradation; thus, they tend to be routed to cellular lysosomes instead of being recycled. This has the effect of increasing the length of time the ligand remains associated with the cell, thereby increasing the probability of delivering the drug. Indeed, MTX conjugates of Tf oligomers were shown to be more cytotoxic than MTX conjugates of native Tf [5]. Although routing conjugate traffic to the lysosome appears effective for MTX, which requires release from Tf to be active, lysosomal degradation may adversely affect the effectiveness of protein drugs such as DT and CRM107. In fact, TfR mAb conjugates of CRM107 are less cytotoxic than Tf conjugates of CRM107, though the reasons for this are not clear [16].

To investigate whether Tf itself could be modified to change its cellular trafficking behavior, we employed a mathematical model of Tf/TfR trafficking. The use of models for the study of the Tf/TfR trafficking system is well-established, though typically such models are used to analyze and better understand experimental data [15, 19]. Here, we have used the model as a convenient framework to allow a mathematical assessment of how changes in intracellular trafficking could result from alteration of Tf properties. By systematically varying the values of seven different Tf parameters, the model indicated that decreasing the rate of iron release from Tf is a potential strategy for increasing cellular association. This design criterion is novel, since it alters the ligand/metal interaction, instead of the ligand/receptor interaction, for the engineering of protein-based drug delivery vehicles.

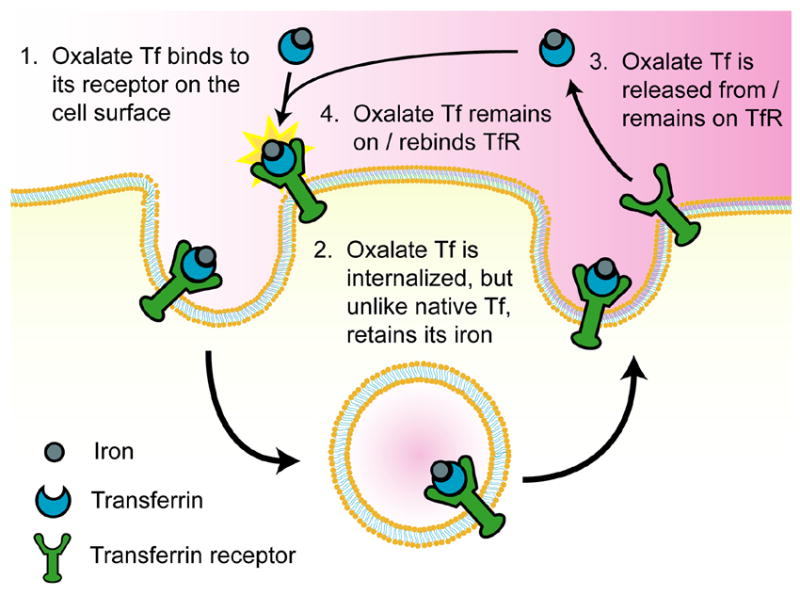

To test the prediction from the model, we generated Tf ligands with reduced iron release rates by replacing the synergistic carbonate anion with oxalate. Oxalate lowers the iron release rate of Tf by increasing the structural stability of the Tf iron binding sites [19] and because it has a lower pKa than carbonate [7]. Oxalate is present normally in the human circulation at micromolar concentrations, and hence its presence would not be expected to be problematic for in vivo administration [26]. Additionally, the oxalate complex of Tf would not be predicted to elicit an immune response. Tf ligands modified with oxalate were found to associate with HeLa cells an average of 51% more than native Tf at concentrations of 0.1 and 1 nM. These results suggest that if the iron release rate of Tf is lowered such that Tf holds its iron upon recycling to the cell surface, then Tf may retain its ability to either bind to or remain associated with TfR, and may thus be reinternalized. This appears to enable Tf to undergo multiple cycles through the cell without having to rebind iron, thereby altering the normal trafficking pathway of Tf to increase its cellular association. This proposed alternative trafficking pathway is illustrated in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Proposed alternative trafficking pathway for oxalate Tf.

We produced conjugates of Tf with the DT cytotoxin to test whether the observed increase in cellular association would translate into improved drug carrier efficacy. HeLa cells were selected for the cytotoxicity assay due to their high expression of transferrin receptors (5.4 × 105 receptors/cell) [15]. In future work, additional cell lines expressing TfR, such as the K562 and HL60 human leukemia cell lines, may be tested to broaden the applicability of the conjugates [27]. DT was selected as a cytotoxin since the effective concentration range of DT (IC50 ~ 0.1 nM) [7] is consistent with the concentration range in which increases in cellular association were observed in the cellular trafficking assay (0.1 and 1 nM, Fig. 4). This is in contrast to cytotoxins such as adriamycin, whose effective concentration range is considerably higher (IC50 ~ 1 μM) [27]. Thus, oxalate Tf conjugates with these cytotoxins would not be expected to display increased efficacy, since differences in cellular association between oxalate Tf and native Tf diminish as concentrations rise to 10 nM (Fig. 4C). In the results of our cytotoxicity assay, oxalate Tf conjugates of DT showed greater cytotoxicity than native Tf conjugates of DT against HeLa cells, with an IC50 value of 0.06 nM compared to 0.22 nM for native Tf conjugates.

Tumor extracellular pH was measured by Gerweck et al. in mice and found to be 6.77, which is somewhat more acidic than the pH of the bloodstream, 7.4 [28]. Intracellular tumor pH was found to be similar to normal tissue. The acidic extracellular pH of tumors was not accounted for in our model, which was designed to guide our in vitro experiments. We would expect the acidic tumor pH to be problematic if it significantly promoted conversion of holo-Tf to apo-Tf before binding of Tf to TfR on the tumor surface. Although apo-Tf has a high affinity for TfR at the acidic pH of the endosome, this high affinity is due in part to protonation of histidines at its TfR binding site [29]. Since histidines have a pKa of 6.4, we would not expect these histidines to be protonated at an extracellular pH of 6.77. Therefore, it is important to consider whether a pH of 6.77 would significantly promote iron release from Tf. The retention of iron as a function of pH has been studied for both native Tf and oxalate Tf [25]. Following a one week equilibration period, it was found that oxalate Tf retained over 90% of its iron at a pH of 6.77, while native Tf retained over 80%. Thus, we would expect the majority of Tf to remain as holo-Tf in the acidic extracellular environment of the tumor and retain its ability to bind to TfR on the tumor surface.

The high concentration of endogenous holo-Tf in the bloodstream (3 – 6 μM) [30] likely precludes the intravenous administration of Tf conjugates in vivo, as any administered conjugates would have difficulty competing with endogenous Tf for binding to TfR. Indeed, intravenously administered imaging agents conjugated with Tf were unable to specifically target tumors in mice [31]. Rather, high concentrations of endogenous Tf will likely necessitate the administration of Tf conjugates within the vicinity of a tumor, as in clinical trials of a Tf-CRM107 conjugate for malignant gliomas [13].

Inhibiting Tf iron release through replacement of carbonate with oxalate may provide a relatively simple and inexpensive method to improve the efficacy of Tf drug carriers through increased association with cancer cells. However, increasing the cellular association of a TfR ligand might also result in an undesired increase in cytotoxicity to normal cells, since TfR is ubiquitously expressed [21]. This may be expected to be the case for ligands such as the TfR mAbs 5E9 and OKT9, which bind to a site on TfR distinct from that of Tf and thus do not compete with endogenous Tf [16, 31]. However, since replacement of carbonate with oxalate does not significantly affect the binding affinity of Tf for TfR, conjugates of oxalate Tf which do not reach their intended target may be unable to bind normal cells due to high levels of endogenous Tf.

Supplementary materials

Sensitivity analysis of parameter uncertainty

Complete set of model parameters

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Sidney Kimmel Scholar Award to D.T.K and by USPHS Grant R01 DK21739 to A.B.M.

5. Appendix

5.1. Model Assumptions

Several assumptions are used to define the behavior of the model, and are described below.

Total Tf receptor number is assumed to be constant. As receptors are degraded, they are replaced through the production of an equal number of new receptors.

Internalization rate is assumed to be the same for free receptors as for bound receptors.

Tf/TfR complexes with inhibited iron release are assumed to be recycled to the cell surface like native Tf/TfR complexes, as opposed to being degraded. This is supported by studies on the effects of lysosomotropic agents on the Tf/TfR cycle. Lysosomotropic agents raise the pH level in the endosome, and hence slow the rate of iron release from Tf. The administration of such agents was not found to inhibit the recycling of Tf to the cell surface [19].

Direct measurements of the iron release rate within cellular endosomes, kFe,rel, are unavailable. However, it is known that iron is completely released from Tf that has been internalized into the endosome before Tf is recycled to the cell surface [19]. Therefore, an iron release rate of 100 min−1 was assumed in the model, which allows all iron from native Tf to be released prior to it being recycled to the cell surface.

For the endosomal sorting component of the model, Tf/TfR complexes are assumed to not associate with endosomal retention complexes which promote the degradation of ligand/receptor complexes [32]. This is consistent with the observation that native Tf is almost completely recycled.

The partition coefficient, κ, was calculated according to the expression κ = (1-λ)2, where λ is the diameter of Tf divided by the diameter of the tubule [32]. An average Tf diameter of 60 nM was estimated from the crystal structure of Tf [33], and a tubule diameter of 600 nM was assumed [34].

5.2. Sensitivity Analysis of Parameter Uncertainty

A sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the impact of parameter uncertainty on the prediction that lowering the Tf iron release rate increases cellular association. The AUC values in Fig. 3G were recalculated while setting the value for a particular variable to the lower or upper range of its error interval. The AUC values show the most sensitivity to variations across the error intervals of kFeTf,TfR and kFeTf,TfR,r (Fig. S1A), and are relatively insensitive to variations across the error intervals of kendo, kendo,r, and kint (Fig. S1B). In each case where a parameter was varied, lowering the iron release rate was still predicted to increase cellular association.

5.3. Model Equations

5.3.1. Bulk & Surface Equations

Species balance for bulk extracellular FeTf

| (1) |

Species balance for bulk extracellular Tf

| (2) |

Species balance for surface TfR

| (3) |

Species balance for surface FeTf/TfR complex

| (4) |

Species balance for surface Tf/TfR complex

| (5) |

5.3.2. Vesicular Equations

Species balance for vesicular FeTf

| (6) |

Species balance for vesicular Tf

| (7) |

Species balance for vesicular TfR

| (8) |

Species balance for vesicular FeTf/TfR complex

| (9) |

Species balance for vesicular Tf/TfR complex

| (10) |

5.3.3. Tubular Equations

Species balance for tubular FeTf/TfR complex

| (11) |

Species balance for tubular Tf/TfR complex

| (12) |

Species balance for tubular TfR

| (13) |

5.3.4. Recycling Equations

Species balance for recycled FeTf

| (14) |

Species balance for recycled Tf

| (15) |

Species balance for recycled TfR

| (16) |

Species balance for recycled FeTf/TfR complex

| (17) |

Species balance for recycled Tf/TfR complex

| (18) |

5.3.5. Degradation Equations

Species balance for degraded FeTf

| (19) |

Species balance for degraded Tf

| (20) |

Species balance for degraded TfR

| (21) |

Species balance for degraded FeTf/TfR complex

| (22) |

Species balance for degraded Tf/TfR complex

| (23) |

5.3.6. Internalized Tf Equation

Species balance for total internalized Tf

| (24) |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cazzola M, Bergamaschi G, Dezza L, Arosio P. Manipulations of cellular iron metabolism for modulating normal and malignant cell proliferation: achievements and prospects. Blood. 1990;75(10):1903–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reizenstein P. Iron, free radicals and cancer. Med Oncol Tumor Pharmacother. 1991;8(4):229–33. doi: 10.1007/BF02987191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saul JM, Annapragada AV, Bellamkonda RV. A dual-ligand approach for enhancing targeting selectivity of therapeutic nanocarriers. J Control Release. 2006;114(3):277–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kreitman RJ. Immunotoxins for targeted cancer therapy. Aaps J. 2006;8(3):E532–51. doi: 10.1208/aapsj080363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lim CJ, Shen WC. Transferrin-oligomers as potential carriers in anticancer drug delivery. Pharm Res. 2004;21(11):1985–92. doi: 10.1023/b:pham.0000048188.69785.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lai H, Sasaki T, Singh NP, Messay A. Effects of artemisinin-tagged holotransferrin on cancer cells. Life Sci. 2005;76(11):1267–79. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson VG, Wilson D, Greenfield L, Youle RJ. The role of the diphtheria toxin receptor in cytosol translocation. J Biol Chem. 1988;263(3):1295–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beyer U, Rothern-Rutishauser B, Unger C, Wunderli-Allenspach H, Kratz F. Differences in the intracellular distribution of acid-sensitive doxorubicin-protein conjugates in comparison to free and liposomal formulated doxorubicin as shown by confocal microscopy. Pharm Res. 2001;18(1):29–38. doi: 10.1023/a:1011018525121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu-Lieskovan S, Heidel JD, Bartlett DW, Davis ME, Triche TJ. Sequence-specific knockdown of EWS-FLI1 by targeted, nonviral delivery of small interfering RNA inhibits tumor growth in a murine model of metastatic Ewing’s sarcoma. Cancer Res. 2005;65(19):8984–92. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tros De Ilarduya C, Bunuales M, Qian C, Duzgunes N. Antitumoral activity of transferrin-lipoplexes carrying the IL-12 gene in the treatment of colon cancer. J Drug Target. 2006;14(8):527–35. doi: 10.1080/10611860600825282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maruyama K, Ishida O, Kasaoka S, Takizawa T, Utoguchi N, Shinohara A, Chiba M, Kobayashi H, Eriguchi M, Yanagie H. Intracellular targeting of sodium mercaptoundecahydrododecaborate (BSH) to solid tumors by transferrin-PEG liposomes, for boron neutron-capture therapy (BNCT) J Control Release. 2004;98(2):195–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiu SJ, Liu S, Perrotti D, Marcucci G, Lee RJ. Efficient delivery of a Bcl-2-specific antisense oligodeoxyribonucleotide (G3139) via transferrin receptor-targeted liposomes. J Control Release. 2006;112(2):199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weaver M, Laske DW. Transferrin receptor ligand-targeted toxin conjugate (Tf-CRM107) for therapy of malignant gliomas. J Neurooncol. 2003;65(1):3–13. doi: 10.1023/a:1026246500788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yazdi PT, Wenning LA, Murphy RM. Influence of cellular trafficking on protein synthesis inhibition of immunotoxins directed against the transferrin receptor. Cancer Res. 1995;55(17):3763–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yazdi PT, Murphy RM. Quantitative analysis of protein synthesis inhibition by transferrin-toxin conjugates. Cancer Res. 1994;54(24):6387–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wenning LA, Yazdi PT, Murphy RM. Quantitative analysis of protein synthesis inhibition and recovery in CRM107 immunotoxin-treated HeLa cells. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1998;57(4):484–96. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0290(19980220)57:4<484::aid-bit13>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarkar CA, Lowenhaupt K, Horan T, Boone TC, Tidor B, Lauffenburger DA. Rational cytokine design for increased lifetime and enhanced potency using pH-activated “histidine switching”. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20(9):908–13. doi: 10.1038/nbt725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hinton PR, Johlfs MG, Xiong JM, Hanestad K, Ong KC, Bullock C, Keller S, Tang MT, Tso JY, Vasquez M, Tsurushita N. Engineered human IgG antibodies with longer serum half-lives in primates. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(8):6213–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300470200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ciechanover A, Schwartz AL, Dautry-Varsat A, Lodish HF. Kinetics of internalization and recycling of transferrin and the transferrin receptor in a human hepatoma cell line. Effect of lysosomotropic agents. J Biol Chem. 1983;258(16):9681–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.French AR, Lauffenburger DA. Controlling receptor/ligand trafficking: effects of cellular and molecular properties on endosomal sorting. Ann Biomed Eng. 1997;25(4):690–707. doi: 10.1007/BF02684846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hentze MW, Muckenthaler MU, Andrews NC. Balancing acts: molecular control of mammalian iron metabolism. Cell. 2004;117(3):285–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00343-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bali PK, Zak O, Aisen P. A new role for the transferrin receptor in the release of iron from transferrin. Biochemistry. 1991;30(2):324–8. doi: 10.1021/bi00216a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lebron JA, Bennett MJ, Vaughn DE, Chirino AJ, Snow PM, Mintier GA, Feder JN, Bjorkman PJ. Crystal structure of the hemochromatosis protein HFE and characterization of its interaction with transferrin receptor. Cell. 1998;93(1):111–23. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rao BM, Lauffenburger DA, Wittrup KD. Integrating cell-level kinetic modeling into the design of engineered protein therapeutics. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23(2):191–4. doi: 10.1038/nbt1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halbrooks PJ, Mason AB, Adams TE, Briggs SK, Everse SJ. The oxalate effect on release of iron from human serum transferrin explained. J Mol Biol. 2004;339(1):217–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Costello J, Landwehr DM. Determination of oxalate concentration in blood. Clin Chem. 1988;34(8):1540–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berczi A, Barabas K, Sizensky JA, Faulk WP. Adriamycin conjugates of human transferrin bind transferrin receptors and kill K562 and HL60 cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;300(1):356–63. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerweck LE, Vijayappa S, Kozin S. Tumor pH controls the in vivo efficacy of weak acid and base chemotherapeutics. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5(5):1275–9. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giannetti AM, Halbrooks PJ, Mason AB, Vogt TM, Enns CA, Bjorkman PJ. The molecular mechanism for receptor-stimulated iron release from the plasma iron transport protein transferrin. Structure (Camb) 2005;13(11):1613–23. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson MB, Enns CA. Diferric transferrin regulates transferrin receptor 2 protein stability. Blood. 2004;104(13):4287–93. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aloj L, Jogoda E, Lang L, Caraco C, Neumann RD, Sung C, Eckelman WC. Targeting of transferrin receptors in nude mice bearing A431 and LS174T xenografts with [18F]holo-transferrin: permeability and receptor dependence. J Nucl Med. 1999;40(9):1547–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anthony DAL, French R. Intracellular receptor/ligand sorting based on endosomal retention components. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 1996;51(3):281–297. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19960805)51:3<281::AID-BIT4>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng Y, Zak O, Aisen P, Harrison SC, Walz T. Structure of the human transferrin receptor-transferrin complex. Cell. 2004;116(4):565–76. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marsh M, Griffiths G, Dean GE, Mellman I, Helenius A. Three-dimensional structure of endosomes in BHK-21 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83(9):2899–903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.9.2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sensitivity analysis of parameter uncertainty

Complete set of model parameters