Abstract

Protein folding in living cells is inherently coupled to protein synthesis and chain elongation. There is considerable evidence that some nascent chains fold into their native structures in a cotranslational manner before release from the ribosome, but, despite its importance, a detailed description of such a process at the atomic level remains elusive. We show here at a residue-specific level that a nascent protein chain can reach its native tertiary structure on the ribosome. By generating translation-arrested ribosomes in which the newly synthesized polypeptide chain is selectively 13C/15N-labeled, we observe, using ultrafast NMR techniques, a large number of resonances of a ribosome-bound nascent chain complex corresponding to a pair of C-terminally truncated immunoglobulin (Ig) domains. Analysis of these spectra reveals that the nascent chain adopts a structure in which a native-like N-terminal Ig domain is tethered to the ribosome by a largely unfolded and highly flexible C-terminal domain. Selective broadening of resonances for a group of residues that are colocalized in the structure demonstrates that there are specific but transient interactions between the ribosome and the N-terminal region of the folded Ig domain. These findings represent a step toward a detailed structural understanding of the cellular processes of cotranslational folding.

Keywords: cotranslational folding

The three-dimensional structures of proteins are inherently determined by their amino acid sequences, and through the process of protein folding the hereditary information contained within the genetic sequence is converted into biological function (1). Our current mechanistic understanding of protein folding at the level of individual residues has come overwhelmingly from a combination of computer simulations and experimental studies of protein denaturation and renaturation in vitro, using biochemical and biophysical methods (2–6). In living cells, however, the folding processes are intricately linked to chain elongation on the ribosome, which occurs in a vectorial manner as the N-terminal part of the nascent chain emerges from the ribosome (7–10). Although recent studies have provided evidence for a degree of structural ordering of nascent chains (11–13), the molecular details of the contribution of the conformational and dynamical restraints imposed by the ribosome on nascent chain folding remain elusive, not the least because of the challenges that arise in applying to such systems the high-resolution physical techniques that can provide the level of structural information required.

Through a series of groundbreaking studies using x-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), ribosome structures have been determined in a variety of functional states and have provided detailed insights into the protein translation machinery (for reviews, see refs. 14–17). In addition, by using cryo-EM methods, localized conformational changes have been observed in Escherichia coli ribosomes under translation arrest, with a range of different nascent chains threading through the ribosomal tunnel (12). The tRNAs to which the nascent chains are attached are clearly visible in these studies, but the nascent chains themselves have not been observed with any certainty, likely because of their inherent flexibility.

The technique that is most amenable to providing residue-specific structural information about dynamic systems is NMR spectroscopy (5, 18). The ribosome, however, has a mass of ≈2.3 MDa and contains >7,500 amino acid residues in the >50 proteins of which it is composed (19). This size suggests that both the resonance linewidths and the complexity of the spectra would be far too great for NMR to be used to study the properties of any nascent chain attached to such a complex. Nonetheless, we and others have shown (20, 21) that a number of well resolved resonances can be observed in NMR spectra of the ribosome itself as a result of the independent motion of localized regions of the structure. This has enabled us to define the structure and dynamics of the L7/L12 proteins in the mobile GTPase-associated region (GAR or stalk region) of the E. coli ribosome that is involved in the regulation of protein elongation (19). If at least part of a nascent chain were to have local dynamical properties similar to those observed for L7/L12, it might be feasible to observe resonances from individual residues of the newly synthesized polypeptide chain as it emerges from the ribosome.

Results and Discussion

To explore the possibility of using NMR to study nascent chains on ribosomes, we used a procedure similar to that used in our earlier cryo-EM study (12) to generate a ternary peptidyl-tRNA-ribosome species, i.e., a translation-arrested RNC. As in the cryo-EM study, we used a DNA template that encodes a tandem Ig domain repeat from the gelation factor ABP-120 of Dictyostelium discoideum (domains 5 and 6) (22), from which the stop codon was removed (see Materials and Methods) by restriction enzyme digestion (12). This template was designated as “Ig2.” We then selectively labeled the nascent chains of the RNCs by using a coupled transcription-translation E. coli cell-free system supplied with the Ig2 DNA template and 13C/15N-labeled amino acids, so that the translation products, i.e., the nascent polypeptide chains, are the only species present in the RNC with the potential to be detected by heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy.

The RNC preparation protocol is depicted schematically in Fig. 1. A particular challenge is that the quantity of material required for NMR studies (10–100 nmol) is larger by a factor of >104 than that needed for biophysical methods such as fluorescence spectroscopy (from single molecules to femtomoles) (13) or cryo-EM (≈10 pmol) (12). We therefore carried out a series of large-scale reactions to generate appropriate quantities of the required RNCs. The resulting reaction mixture was subjected to sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation to separate the RNCs from any dissociated 50S and 30S ribosome subunits, small molecules such as free tRNAs and amino acids, any aggregated material, and, most importantly, any nascent chains free in solution [see supporting information (SI) Fig. 6].

Fig. 1.

Schematic protocol of RNC preparation for NMR studies. (A) Structural model of the ABP-120 domains 5 and 6 [Upper, residues 644–857 of Ig2; Protein Data Bank ID code 1QFH (22)] and the construct used for the Ig2 RNC (Lower). The N-terminal domain (NTD, domain 5) and the C-terminal domain (CTD, domain 6) are designated Ig2 NTD and Ig2 CTD, respectively. The DNA plasmid of the Ig2 was digested at the unique BstNI restriction site, leading to a truncated translation product ending at residue 838, the position at which the last β-strand of the Ig2 CTD begins (highlighted in black and also indicated in the structural model). (B) Schematic description of the experimental protocol for RNC preparation (for further details, see Materials and Methods and SI Fig. 6).

To monitor the structural properties of the Ig2 nascent chain, we used recently developed SOFAST-HMQC spectroscopy (23) to record backbone fingerprint 1H–15N correlation spectra. This relaxation-optimized NMR technique makes use of selective pulses to achieve rapid repetition of data acquisition; in our case, this resulted in an ≈4-fold reduction in data acquisition time relative to conventional techniques, an advance that proved to be critical at these low molar concentrations of the RNC samples. This approach enabled us to acquire NMR spectra with the spectral quality necessary to begin their detailed analysis within 6 h. The resulting 1H–15N correlation spectra of the Ig2 RNC (Fig. 2A) are of remarkable quality given the very large molecular mass of the complex and reveal that at least part of the nascent chain is dynamic. Further analysis of the spectrum shows that the average 1H linewidths (as detected in the 1H dimension of the SOFAST-HMQC experiment for 15N-labeled backbone amides) of the resonances observed in the Ig2 RNC spectrum, 59 ± 26 Hz, are in fact comparable to those of purified recombinant Ig2 protein in the presence of 70S ribosomes (designated Ig2/70S; Fig. 2B), which we measured to be 41 ± 11 Hz. By contrast, the values expected for the 70S ribosome particle are >1,000 Hz (24, 25). The addition of 70S ribosomes to purified Ig2 is done to account for the nonspecific increases in sample viscosity and crowding that are associated with the presence of ribosomes and is a similar control to that used in our previous NMR study of the E. coli ribosome (20).

Fig. 2.

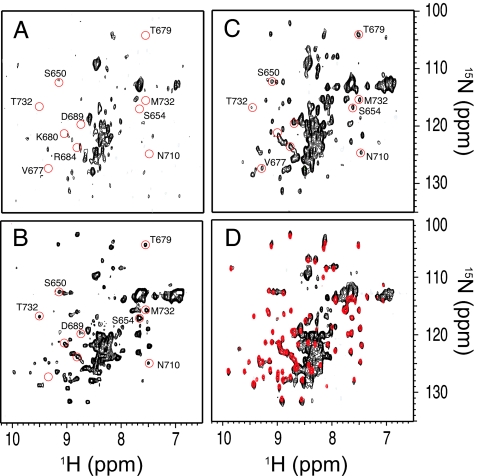

1H–15N correlation spectra of the Ig2 RNC. The SOFAST-HMQC spectra of Ig2 RNC (A), Ig2/70S (B), Ig2 RNC as in A but incubated with 1 mM puromycin (1 h, 25°C) before data acquisition (C), and isolated Ig2 NTD (red) and Ig2 (black) in the absence of 70S ribosomes (D). The cross-peaks that are absent in the Ig2 RNC spectrum (A) are indicated with red circles in A–C and are labeled with the corresponding residue identities. All spectra were recorded under identical conditions (binding buffer, 10°C) and at 700 MHz, except the spectrum in A, which was recorded at 900 MHz.

The spectrum of the Ig2 RNC shows a large number of cross-peaks located in the region between 8.2 and 8.6 ppm along the 1H dimension (Fig. 2A), characteristic of resonances arising from amino acids within an unfolded polypeptide chain, but it includes in addition ≈45 cross-peaks that are well dispersed, indicative of a highly folded protein. Overall, the spectrum shows a marked similarity to that of the Ig2/70S sample (Fig. 2B), and the majority of the well dispersed cross-peaks in the Ig2 RNC spectrum show only marginal chemical shift differences (〈ΔδHN〉 = 0.18 ± 0.17 ppm) from those of the isolated Ig2 NTD. This result is significant because it shows the presence of a highly folded structure of the nascent Ig2 NTD even when attached to the ribosome (Fig. 2) (26, 27). The molecular chaperone, trigger factor, could not be identified in the purified RNCs (see SI Fig. 7), and it is therefore possible that folding of the Ig2 NTD occurred spontaneously in its absence. Trigger factor is known to bind emerging nascent chains at the ribosomal tunnel exit, with higher affinity found for hydrophobic segments of nascent chains (26, 27).

We also carried out 15N-filtered diffusion experiments [X-STE measurements (28)] to monitor the translational diffusion rate of the species giving rise to the observed resonances, an approach similar to that which we used previously to study the mobile region in the ribosome itself (20). The translational diffusion coefficient (Dtrans) observed for the species labeled with the 15N isotope (i.e., the Ig2 nascent chain) is at least four times smaller than that of purified Ig2 in the presence of 70S ribosomes (Ig2/70S), thus setting a lower bound for the apparent molecular mass for the species that gives rise to the observed resonances of ≈1 MDa and thereby confirming that the nascent chain is attached to the ribosome (Fig. 3 and Table 1).

Fig. 3.

Identification of RNCs. 15N-filtered X-STE diffusion NMR measurements of Ig2 RNC (A) and purified Ig2 (B) in the presence of 70S ribosomes (Ig2/70S), recorded at 25°C, 700 MHz. Significant attenuation of the 15N-filtered signal of purified Ig2 was observed in the spectrum recorded with a strong diffusion coding/decoding gradient pair (70% Gzmax, red) flanking the 200-ms diffusion period, compared with the same spectrum recorded with a weak coding/decoding gradient pair (10% Gzmax, black) (B). The same X-STE experiments recorded for the Ig2 RNC (A) showed no discernible intensity changes, indicating the very slow diffusion of the Ig2 RNC as a result of the connection of the nascent chain to the ribosomes. (C) [35S]Met radioactivity profile of sucrose gradients loaded with [35S]Met-labeled Ig2 RNC. Aliquots of [35S]Met-labeled Ig2 RNC were incubated at 25°C to monitor sample stability. No significant release of tRNA-bound nascent chains from the 70S ribosome was found after 8 h of incubation (red curve) vs. without incubation (black curve), whereas incubation in the presence of 1 mM puromycin over the same 8-h period induces very efficient release of the nascent chain (green curve). A time course of puromycin-induced nascent chain release under the same conditions shows that the reaction can be completed within 30 min of incubation (data not shown).

Table 1.

Relative translational diffusion coefficients, Dtrans, determined by 15N-filtered X-STE NMR diffusion experiments

| Protein | Relative Dtrans, %* | Molecular mass, kDa | Apparent molecular mass, kDa† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human lysozyme | 100 (1) | 14 | 14 |

| Ig2 NTD | 107 (3) | 11 | 11 |

| Ig2 | 76 (4) | 21 | 32‡ |

| Ig2/70S | 63 (2) | 32§ | |

| Ig2 RNC | 18 (>10) | >1,300 |

*Relative Dtrans was defined relative to a 15N-labeled human lysozyme sample reference (error estimates are indicated in parentheses), as described elsewhere (28). The relative Dtrans of the Ig2 RNC is estimated from the intensity ratio of the X-STE spectra with 10% and 70% Gzmax integrated over the region from 7.6 to 9.3 ppm in the 1H dimension (see Fig. 4A). Only two gradient points were employed for the Ig2 RNC because of the limited sample concentrations.

†The apparent molecular mass (MM) was derived by using the Stokes–Einstein relationship, MM ∝ (r)3 ∝ (1/Dtrans)3. This estimation assumes a spherical species (of radius r) with a density similar to that of the lysozyme.

‡The apparent MM of Ig2 in aqueous solution is significantly higher than that of a monomeric Ig2 due to its tendency to dimerize (unpublished data).

§The presence, in a sample of isolated Ig2, of a concentration of 70S ribosomes similar to that present in the Ig2 RNC sample (12 μM) reduces the relative Dtrans as a result of the increased sample viscosity. Under the assumption that the change in sample viscosity does not affect the monomer–dimer equilibrium of Ig2, and that the sample viscosity is dominated by the concentration of 70S ribosomes, the apparent MM of Ig2 derived from aqueous solution (32 kDa) was then used to determine the apparent MM of the Ig2 RNC. When human lysozyme is used as a reference without correcting for sample viscosity, the apparent MM of Ig2 RNC is found to be 2.4 MDa.

To further verify that the nascent chain is associated with the ribosome, nascent chains labeled with [35S]Met were found to be efficiently released from the ribosome by the addition of puromycin, a phenylalanine-mimicking antibiotic that reacts specifically with the peptidyl-tRNA in the 70S ribosome (Fig. 3C). Addition of puromycin to the NMR sample after recording the 1H–15N correlation spectra (Fig. 2C) resulted in an overall signal increase of 62 ± 7%, as assessed by integrating the signal intensities over the region of 7.5–8.5 ppm along the 1H dimension of the 1H–15N correlation spectra. On release from the ribosomal tunnel, the Ig2 CTD remains largely unfolded (Fig. 2C) as a result of the designed absence of the last β-strand in the construct (see Materials and Methods). This intensity increase reflects the increased dynamics of the nascent chain as a consequence of its release from the ribosome, which occurs without significant structural perturbations, as reflected in the very marginal chemical shift changes, 〈ΔδHN〉 = 0.10 ± 0.07 ppm (Fig. 2C).

To obtain insight into the dynamical restraints on the nascent chain resulting from its attachment to the ribosome, we examined the linewidths of the resolved resonances of the Ig2 NTD in the spectrum of the Ig2 RNC (Fig. 2A). We found that a number of cross-peaks of the Ig2 NTD exhibit differential line broadening (Fig. 4); in particular, the cross-peaks of 10 residues in the Ig2 RNC spectrum are broadened beyond detection (highlighted in Figs. 2 and 4B). Remarkably, mapping of the residues whose resonances exhibit significantly broader 1H linewidths on the structure of the Ig2 NTD reveals that all of these, apart from V729, are located in loop regions of the native structure (filled orange circles in Fig. 5). The localized line broadening of the resonances of G697 and N677, as well as the missing cross-peak of I748, can be attributed to their spatial proximity to the flexible and structurally heterogeneous Ig2 CTD that tethers the nascent chain to the peptidyl transferase center through the ribosomal tunnel. The much greater line broadening observed in the N-terminal hemisphere of the Ig2 NTD (Fig. 5), however, suggests that there are preferential, albeit transient, intermolecular interactions between this region of the nascent chain and the ribosome, which are lost upon its release.

Fig. 4.

Differential line broadening in the Ig2 NTD of the Ig2 RNC. (A) Representative regions of the SOFAST-HMQC spectra of the Ig2 RNC (Left) and Ig2/70S (Right), as shown in Fig. 2 A and B, respectively. Cross-peaks that show significantly broader linewidths in the Ig2 RNC spectrum are indicated with dashed circles. The cross-peak of residue I748, which is adjacent to the domain boundary between the Ig2 NTD and CTD (Fig. 1A), cannot be identified in the Ig2 RNC spectrum (Left). (B) 1H linewidth profiles of the Ig2 NTD in the Ig2 RNC (black open circles) and Ig2/70S (green line) obtained from the corresponding 1H–15N SOFAST-HMQC spectra (Fig. 2 A and B). The residues in the Ig2 NTD in the Ig2 RNC whose cross-peaks exhibit severe line broadening are indicated by filled red circles, with those that exhibit linewidths >1 standard deviation above the average (dashed horizontal line) indicated by filled orange circles. Residues that are part of the β-strands of the Ig2 NTD are indicated by black arrows.

Fig. 5.

Structural mapping of the locations of the Ig2 RNC that experience NMR line broadening. (A) Schematic representation of Ig2 RNC showing relative sizes (approximate) of the 70S ribosome and the Ig2 NTD (boxed), with the loop regions in the N-terminal hemisphere that appear to interact with the ribosome indicated in red. (B) Mapping of the residues whose resonances are broadened on the structure of Ig2 NTD, depicted in ribbon representation [Protein Data Bank ID code 1QFH (22)]. The heavy atoms of those residues whose resonances are broadened by >1 standard deviation from the average (filled orange circles in Fig. 2B) and those that are broadened beyond detection in the Ig2 RNC spectra (filled red circles in Fig. 2B) are shown as orange and red spheres, respectively, and labeled with their residue identities. Residue I748, which lies at the domain boundary and whose cross-peak is absent in the Ig2 RNC spectrum (Fig. 4A), is shown by green spheres. The figure was generated by using PyMol (www.pymol.org).

Conclusions

We have demonstrated that NMR spectra of remarkable quality can be obtained from a nascent polypeptide chain attached to a ribosome, through a combination of selective isotope labeling using cell-free expression, ultrafast NMR spectroscopy, NMR diffusion measurements, and biochemical assays. Analysis of the spectra of the Ig2 construct studied here has shown not only that the C-terminal Ig domain is unfolded when attached to the ribosome, but also that it is sufficiently mobile to enable us to show that the remainder of the nascent chain, the Ig2 NTD, has folded to its fully native state despite retaining some interactions with the ribosome surface.

The ability to record high-resolution NMR spectra of nascent chains provides an avenue of opportunity for obtaining a detailed description of the steps involved in the process of cotranslational folding at a residue-specific level. This understanding could be spurred by recent advances in our ability to define protein structures and dynamics (5, 29, 30) by using a variety of NMR parameters that can be collected even from large biomolecular assemblies of great biological interest (31, 32). Together, these developments serve as a vantage point for probing (in synergy with the information obtainable from x-ray crystallographic and cryo-EM studies) the manner in which auxiliary factors such as molecular chaperones help an elongating polypeptide chain to fold into a specific structure and to avoid misfolding and its potential pathogenic consequences (6, 33).

Materials and Methods

Sample Constructs.

The DNA sequence of domains 5 and 6 of the gelation factor ABP-120 from D. discoideum (residues 644–838) was cloned and digested by BstNI, as described previously (12). A stop codon was reintroduced in the truncation site by PCR, and the resulting DNA template is designated Ig2. Similarly, a stop codon was introduced at the boundary between the domains to obtain an isolated domain 5 construct (residues 644–750), i.e., the NTD of the Ig2, designated Ig2 NTD. Both DNA constructs were transformed into an E. coli BL21 strain for protein overexpression.

Preparation of Ribosome-Nascent Chain Complexes.

We used a coupled transcription–translation E. coli cell-free system (RTS100 E. coli HY kit; Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). The truncated DNA plasmids and a 13C,15N, >98%-labeled amino acid mix (Spectra Stable Isotopes, Columbia, MD) were supplied to achieve selective labeling of the nascent chains in the RNC for NMR measurements. With the truncated DNA template of the Ig2 construct, an RNA transcript was created in the cell-free reaction without a stop codon at the 3′ end, which leads to translation arrest when the ribosome reaches the end of this transcript. To monitor the reaction product, [35S]methionine (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) was added to small, separated aliquots of these NMR-scale reaction mixtures. All expression reactions were carried out at 25°C for 30 min, and reactions were stopped by adding equal volumes of ice-chilled S30 buffer (10 mM Tris-OAc, pH 8.2/60 mM K-OAc/14 mM Mg-OAc/1 mM DTT) to the sample. The reaction products were layered onto 10–30% sucrose gradients in S30 buffer for ultracentrifugation at 4°C for 16 h in an SW32Ti rotor (all rotors are Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) for NMR samples [maximum relative centrifugal force (max. rcf) 68,000 × g] and for 18 h in a SW40 rotor for 35S-containing samples (max. rcf 71,000 × g). These sucrose gradients were fractionated and monitored by optical absorbance at 254 nm. Fractions corresponding to 70S ribosomes were pooled and pelleted by ultracentrifugation at 4°C for 22 h in a 45Ti (max. rcf 126,000 × g) and a 50Ti rotor (max. rcf 98,500 × g) for NMR and radioactively labeled samples, respectively. The pellets were then resuspended with binding buffer (10 mM Hepes, pH 7.6/140 mM NH4Cl/6 mM MgCl2/0.005 mM spermine/2 mM spermidine/2 mM DTT) by shaking at 4°C for 1 h. The concentration of 70S ribosomes was determined by the optical absorbance at 260 nm (one A260 unit = 24 pmol 70S). The resuspended RNC samples were divided into aliquots, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Typically, the cell-reaction size is 10 ml, which proved sufficient to give two reproducible NMR samples after being subjected to the purification procedure described above.

Preparation of Isolated Ig2 and E. coli 70S Ribosomes.

Uniformly 13C,15N-labeled Ig2 NTD and Ig2 polypeptides were overexpressed in minimal medium and purified as described previously (22). The purified proteins were then concentrated to 300–500 μM in buffer (20 mM KPi, pH 7.0/2 mM EDTA/2 mM 2-mercaptoethanol). E. coli 70S ribosomes were purified by zonal sucrose-gradient centrifugation and were dialyzed against Tico buffer (10 mM Hepes, pH 7.6/30 mM NH4Cl/6 mM MgCl2/2 mM 2-mercaptoethanol). Purified 70S ribosomes were divided into aliquots, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Uniformly 15N-labeled Ig2, which has an identical sequence to that of the Ig2 nascent chain prepared from the cell-free reactions, was mixed with purified 70S ribosomes solution (Ig2 and 70S ribosome concentrations were 100 μM and 12 μM, respectively, in this Ig2/70S sample). The Ig2/70S sample was then exchanged into the same binding buffer used for RNC samples, for spectral comparison.

NMR Spectroscopy.

All RNC samples (70S ribosome concentrations of 12 μM) were prepared in binding buffer. NMR data were recorded by using Bruker 700-MHz and 900-MHz spectrometers (Bruker BioSpin, Karlsruhe, Germany), both equipped with triple resonance cryogenic probeheads. As a lock solvent, 10% D2O was present in all NMR samples. 1H–15N SOFAST-HMQC spectra (23) were recorded by using a 300-ms recycling delay with 1,024 × 64 complex points collected in the 1H and 15N dimensions, respectively, and 1,024 transients per increment. 15N-edited X-STE diffusion measurements (28) with varied diffusion coding gradient strengths (3 ms total duration) were recorded by using a diffusion delay of 200 ms with 2,048 transients. These two experiments, SOFAST-HMQC and X-STE diffusion measurements, were carried out in an interleaved manner, allowing the integrity of the RNC to be ascertained. These experiments were also recorded with the reconstituted Ig2/70S sample for comparison. 1H PFG-LED diffusion measurements (34) were also recorded for RNC samples, to monitor the translational diffusion of the 70S ribosome by using the observable proton resonances of the stalk L7/L12 proteins (20). HNCO experiments (1H–15N or 1H–13C correlation projections) were recorded and revealed that the observed 1H–15N correlations in the SOFAST-HMQC spectra could not arise from free amino acids because the presence of a peptide bond is the prerequisite for detection of HiNiCOi−1 correlations (35). For backbone assignments of the isolated Ig2 NTD spectra, the standard triple resonance experiments [HNCA, HN(CO)CA, CBCA(CO)NH, HNCACB, HNCO, HN(CA)CO, and 15N-TOCSY-HSQC spectra (35)] were recorded at 25°C at 700 MHz in the absence of the ribosome. The chemical shifts of individual spin systems (HN, N, CA, CB, CO, and HA) were collected manually for automated assignment using the program MARS (36). High-resolution 1H–15N HSQC spectra (2,048 × 200 complex points) of the Ig2 NTD and Ig2 were recorded at several temperatures ranging from 10° to 25°C to facilitate assignment of the resolved cross-peaks in Ig2 RNC SOFAST-HMQC spectra by following the minimum chemical shift displacement criterion. All NMR data were processed and analyzed by XWIN-NMR (Bruker BioSpin), NMRPipe (37), and Sparky (38) software packages. The linewidth analyses were carried out by using the two-dimensional cross-peak fitting routine in Sparky, assuming Gaussian line shapes with visual inspection of the fitting quality in each case. Twenty-nine and 59 cross-peaks in the Ig2 RNC and Ig2/70S, respectively, were analyzed to obtain the mean values of linewidths (Fig. 4). Thirty-two nonoverlapping cross-peaks that are commonly present in the spectrum of Ig2 RNC before and after the addition of puromycin, and also in the spectrum of Ig2/70S, were used to obtain the 1H- and 15N-weighted chemical shift displacement given by ΔδHN = [(ΔδH)2 + (0.65ΔδN)2]1/2.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff and acknowledge the use of the Biomolecular NMR Facility, Department of Chemistry, University of Cambridge. S.-T.D.H. is a recipient of a Netherlands Ramsay Fellowship and a Human Frontier Long-Term Fellowship. L.D.C. is a National Health and Medical Research Council C. J. Martin Fellow. P.F. and J.C. are recipients of a Human Frontier Young Investigators Award (RGY67/2007). C.M.D. and J.C. acknowledge funding from The Wellcome Trust and The Leverhulme Trust. The 900-MHz spectra were recorded at the SON NMR Large-Scale Facility, Utrecht, The Netherlands, which is funded by the European Union project “EU-NMR-European Network of Research Infrastructures for Providing Access and Technological Advancement in Bio-NMR.”

Abbreviations

- CTD

C-terminal domain

- NTD

N-terminal domain

- RNC

ribosome-bound nascent chain complex.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0704664104/DC1.

References

- 1.Anfinsen CB. Science. 1973;181:223–230. doi: 10.1126/science.181.4096.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dinner AR, Sali A, Smith LJ, Dobson CM, Karplus M. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:331–339. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01610-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brockwell DJ, Smith DA, Radford SE. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2000;10:16–25. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(99)00043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daggett V, Fersht A. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:497–502. doi: 10.1038/nrm1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vendruscolo M, Dobson CM. Philos Trans R Soc London Ser A. 2005;363:433–450. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2004.1501. discussion 450–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiti F, Dobson CM. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:333–366. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.101304.123901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fedorov AN, Baldwin TO. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32715–32718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.32715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicola AV, Chen W, Helenius A. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:341–345. doi: 10.1038/14032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frydman J, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Hartl FU. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:697–705. doi: 10.1038/10754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kramer G, Ramachandiran V, Hardesty B. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2001;33:541–553. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(01)00044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Etchells SA, Hartl FU. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:391–392. doi: 10.1038/nsmb0504-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilbert RJC, Fucini P, Connell S, Fuller SD, Nierhaus KH, Robinson CV, Dobson CM, Stuart DI. Mol Cell. 2004;14:57–66. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00163-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson AE. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:916–920. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramakrishnan V. Cell. 2002;108:557–572. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00619-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noller HF. Science. 2005;309:1508–1514. doi: 10.1126/science.1111771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moore PB, Steitz TA. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:281–283. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitra K, Frank J. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2006;35:299–317. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.040405.101950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mittermaier A, Kay LE. Science. 2006;312:224–228. doi: 10.1126/science.1124964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson DN, Nierhaus KH. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;40:243–267. doi: 10.1080/10409230500256523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christodoulou J, Larsson G, Fucini P, Connell SR, Pertinhez TA, Hanson CL, Redfield C, Nierhaus KH, Robinson CV, Schleucher J, Dobson CM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10949–10954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400928101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mulder FAA, Bouakaz L, Lundell A, Venkataramana M, Liljas A, Akke M, Sanyal S. Biochemistry. 2004;43:5930–5936. doi: 10.1021/bi0495331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCoy AJ, Fucini P, Noegel AA, Stewart M. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:836–841. doi: 10.1038/12296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schanda P, Kupce E, Brutscher B. J Biomol NMR. 2005;33:199–211. doi: 10.1007/s10858-005-4425-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amand B, Pochon F, Lavalette D. Biochimie. 1977;59:779–784. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(77)80207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tritton TR. FEBS Lett. 1980;120:141–144. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(80)81065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agashe VR, Guha S, Chang HC, Genevaux P, Hayer-Hartl M, Stemp M, Georgopoulos C, Hartl FU, Barral JM. Cell. 2004;117:199–209. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00299-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaiser CM, Chang HC, Agashe VR, Lakshmipathy SK, Etchells SA, Hayer-Hartl M, Hartl FU, Barral JM. Nature. 2006;444:455–460. doi: 10.1038/nature05225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrage F, Zoonens M, Warschawski DE, Popot JL, Bodenhausen G. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:2541–2545. doi: 10.1021/ja0211407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korzhnev DM, Salvatella X, Vendruscolo M, Di Nardo AA, Davidson AR, Dobson CM, Kay LE. Nature. 2004;430:586–590. doi: 10.1038/nature02655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindorff-Larsen K, Best RB, Depristo MA, Dobson CM, Vendruscolo M. Nature. 2005;433:128–132. doi: 10.1038/nature03199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fiaux J, Bertelsen EB, Horwich AL, Wuthrich K. Nature. 2002;418:207–211. doi: 10.1038/nature00860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sprangers R, Kay LE. Nature. 2007;445:618–622. doi: 10.1038/nature05512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hartl FU, Hayer-Hartl M. Science. 2002;295:1852–1858. doi: 10.1126/science.1068408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones JA, Wilkins DK, Smith LJ, Dobson CM. J Biomol NMR. 1997;10:199–203. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sattler M, Schleucher J, Griesinger C. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 1999;34:93–158. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jung YS, Zweckstetter M. J Biomol NMR. 2004;30:11–23. doi: 10.1023/B:JNMR.0000042954.99056.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goddard TD, Kneller DG. SPARKY 3. San Francisco: Univ of California; 2004. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.