Abstract

Kutznerides, actinomycete-derived cyclic depsipetides, consist of six nonproteinogenic residues, including a highly oxygenated tricyclic hexahydropyrroloindole, a chlorinated piperazic acid, 2-(1-methylcyclopropyl)-glycine, a β-branched-hydroxy acid, and 3-hydroxy glutamic acid, for which biosynthetic logic has not been elucidated. Herein we describe the biosynthetic gene cluster for the kutzneride family, identified by degenerate primer PCR for halogenating enzymes postulated to be involved in biosyntheses of these unusual monomers. The 56-kb gene cluster encodes a series of six nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) modules distributed over three proteins and a variety of tailoring enzymes, including both mononuclear nonheme iron and two flavin-dependent halogenases, and an array of oxygen transfer catalysts. The sequence and organization of NRPS genes support incorporation of the unusual monomer units into the densely functionalized scaffold of kutznerides. Our work provides insight into the formation of this intriguing class of compounds and provides a foundation for elucidating the timing and mechanisms of their biosynthesis.

Keywords: chlorination, halogenases, nonribosomal peptide biosynthesis

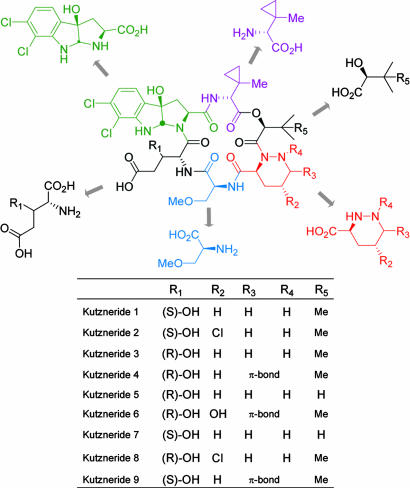

Kutznerides are antifungal and antimicrobial cyclic hexadepsipeptides isolated from the soil actinomycete Kutzneria sp. 744 (1). Structural elucidation of these metabolites revealed nine related compounds composed of five unusual nonproteinogenic amino acids and one hydroxy acid (Fig. 1) but differing in the extent of substitution and stereochemistry of constituent residues (2). All kutznerides contain 2-(1-methylcyclopropyl)-d-glycine (MecPGly) connected to the α-hydroxyl moiety of either (S)-2-hydroxy-3-methylbutyric or (S)-2-hydroxy-3,3-dimethylbutyric acid. The hydroxy acid residue is followed by a piperazic acid moiety, found in four distinct forms: as piperazic acid in kutznerides 1, 3, 5, and 7; as dehydropiperazate in kutznerides 4 and 9; as γ-chloro-piperazate in kutznerides 2 and 8; and as γ-hydroxy-dehydropiperazate in kutzneride 6. Furthermore, kutznerides contain O-methyl-l-serine and either the threo or erythro isomer of 3-hydroxy-d-glutamate. Finally, an unusual tricyclic dihalogenated (2S,3aR,8aS)-6,7-dichloro-3a-hydroxy-hexahydropyrrolo[2,3-b]indole-2-carboxylic acid (PIC) is conserved in all structurally characterized kutznerides. The structural subunits of kutznerides suggest unusual enzymatic mechanisms involved in their biosynthesis.

Fig. 1.

Structures of kutznerides 1–9.

Recently, our laboratory has elucidated the enzymatic logic of carbon–chlorine bond formation during the biosynthesis of several chlorinated secondary metabolites. Among these, dichlorination of the pyrrole moiety in the biosynthesis of pyoluteorin (3) and chlorination of tryptophan in rebeccamycin biosynthesis (4) are carried out by the flavin-dependent halogenases PltA and RebH, respectively. The work of van Pee and coworkers (5) on the pyrrolnitrin halogenase PrnA demonstrated the necessity of FADH2, chloride, and oxygen for catalytic activity of flavoprotein halogenases. The addition of chloride to the terminal oxygen of a FAD-C4a-OOH intermediate in these enzymes generates reactive hypochlorous acid, which is proposed to react with the enzyme's active-site lysine to form lysine chloramine as the active halogenating species (6). Because chloride is transferred as a Cl+ equivalent, only electron-rich carbon centers in substrates can be chlorinated. By contrast, chlorination of unactivated carbon centers is carried out by the class of nonheme iron enzymes represented by the syringomycin halogenase SyrB2 (7), the barbamide halogenases BarB1 and BarB2 (8), and the aliphatic halogenase CytC3 (9). These enzymes chlorinate an unactivated methyl group of protein thiolation (T)-domain-tethered amino acids and require Fe(II), oxygen, chloride, and α-ketoglutarate for activity. Substrate activation is achieved by hydrogen atom abstraction by an Fe(IV)-oxo species (10), resulting in a HO-Fe(III)-Cl intermediate that transfers a chlorine atom to the substrate radical, resulting in the formation of product. Studies on the biosynthesis of coronamic acid (1-amino-1-carboxy-2-ethyl cyclopropane) showed that the cyclopropane moiety is formed via a cryptic chlorination pathway (11). A T-domain-tethered γ-chloro-allo-Ile thioester is the substrate for the cyclopropane-forming enzyme CmaC, which catalyzes the intramolecular displacement of chloride by a thioester-stabilized aminoacyl α-carbanion (12). Combined, these studies demonstrated that halogenating enzymes not only account for the production of chlorinated secondary metabolites in bacteria but also are involved in the formation of chlorinated intermediates during the biosynthesis of cyclopropane residues.

We postulate that the MecPGly residue in kutznerides could arise from a cryptic chlorination pathway involving such a nonheme iron halogenase, although through a different enzymatic logic to that of CmaC-catalyzed cyclopropane formation, given the attachment of the cyclopropane ring to Cβ, rather than the Cα of the amino acid. Furthermore, the presence of two halogenated residues, 6,7-dichlorinated hexahydropyrroloindole in all isolated kutznerides and 4-chloropiperazate in kutznerides 2 and 8, implicates flavin-dependent halogenases in kutzneride biosynthesis. We hypothesized that the gene cluster responsible for the biosynthesis of these secondary metabolites could be identified by degenerate primer-based PCR amplification of highly conserved mononuclear nonheme iron (9, 13, 14) and flavin-dependent halogenase sequences (15–18) in a cosmid library constructed from genomic DNA. Herein, we use this strategy to find the biosynthetic gene cluster of kutznerides, which reveals that these hexadepsipeptides are biosynthesized on a modular nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) assembly line. The most striking feature of the gene cluster is the large number of genes encoding for tailoring enzymes that carry out oxidative transformations. In addition to the three predicted halogenating enzymes, there are two Fe(II)-αKG-dependent dioxygenases, a flavin-dependent oxygenase and a cytochrome P450. Bioinformatic analysis of the function of NRPS modules and modifying enzymes has allowed for prediction of enzymatic steps leading to the biosynthesis of the unusual building blocks and their order of utilization during chain growth. The identity of the cluster has been confirmed via the analysis of amino acid activation specificity of three of the seven constituent adenylation domains.

Results and Discussion

Identification of Kutzneride Cluster from Kutzneria sp. 744.

The producing organism that yields kutznerides 1–9 was cultivated as described (1) and its genomic DNA isolated. Amplicons obtained by PCR using genomic DNA as a template and degenerate primers for both flavin and mononuclear nonheme iron halogenases [supporting information (SI) Table 2] were sequenced, identifying two distinct flavin-dependent halogenases and one Fe(II)-dependent halogenase. Specific primers were thereby designed (SI Table 2) and used to screen a cosmid library of genomic DNA. The cosmid library was prepared by cloning 30- to 50-kb fragments followed by lambda-phage transduction and preparation of 50 liquid gel culture pools (19), each harboring ≈60 colonies. Positive pools identified with specific primers were plated and positive colonies identified. No single colony harboring both nonheme iron and the two flavin halogenase genes was identified. Further PCR screening with primers specific for ends of DNA inserts identified two colonies with sequence overlap, one containing genes for both flavin halogenases and the other with the nonheme iron halogenase. The two inserts from these colonies were fully sequenced (Agencourt Bioscience, Beverley, MA).

Analysis of Kutzneride Gene Cluster.

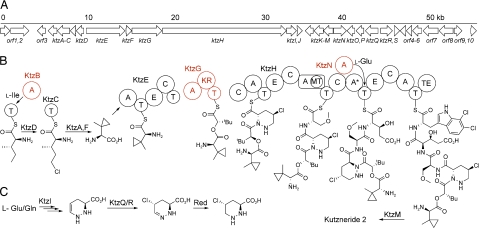

The biosynthetic gene cluster of kutznerides spans ≈56 kb of genomic DNA and consists of 29 ORFs, 17 of which can be assigned roles in kutzneride biosynthesis (Fig. 2A and Table 1). In analogy to other bacterial secondary metabolites (20), biosynthesis of kutznerides is carried out in thiotemplated fashion, where intermediates are covalently tethered to phosphopantetheinyl arms of carrier proteins. NRPS are multidomain enzymes that in each module perform amino acid activation via adenylation (A) domain-catalyzed acyl-AMP formation, loading of the adenylated intermediate to the adjacent T domain, and condensation (C) domain-catalyzed peptide bond formation. The kutzneride cluster encodes three multidomain NRPS proteins, KtzE, KtzG, and KtzH, that make up the six required modules. We propose that four stand-alone proteins, A domains KtzB and KtzN, the T domain KtzC, and the α/β-hydrolase-fold enzyme KtzF also function in the assembly line (Table 1). At least nine tailoring enzymes are encoded by the remaining genes found in the cluster. Eight of these proteins likely catalyze oxidative transformations, including the acyl-CoA dehydrogenase-like protein KtzA, the mononuclear nonheme iron halogenase KtzD, the flavoprotein monooxygenase KtzI, the cytochrome P450 monooxygenase KtzM, the mononuclear nonheme iron dioxygenases KtzO and KtzP, and the flavin-dependent halogenases KtzQ and KtzR. KtzS is predicted to be a dedicated flavin reductase. In addition, the kutznerides gene cluster harbors an S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferase KtzL and several genes postulated to be involved in regulating the production of and resistance to kutznerides. A set of genes adjacent to ktzS has been identified, with unclear correlation to the production of kutznerides. Evaluation of the essentiality of these genes will likely require establishment of a genetic system in Kutzneria or functional characterization of their protein products.

Fig. 2.

Map of sequenced ktz genes and proposed biosynthetic pathway of kutznerides. (A) Organization of ktz genes. (B) Proposed biosynthesis of kutzneride 2. Proteins assayed in ATP-PPi exchange experiments are indicated in red. (C) Proposed biosynthesis of γ-chloro-piperazate residue. Domain notation: T, thiolation; A, adenylation; E, epimerization; C, condensation; KR, ketoreductase; MT, methyltransferase; TE, thioesterase.

Table 1.

Deduced function of ORFs in kutznerides biosynthetic gene cluster

| Protein | Amino acid | Proposed function | Sequence similarity | Identity/similarity, % | GenBank accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF1 | 408 | Permease | BH3211, Bacillus halodurnas C-125 | 32/53 | NP_244077 |

| ORF2 | 781 | Penicillin acylase | STH69, Symbiobacterium thermophilium IAM 14863 | 37/49 | YP_073898 |

| ORF3 | 344 | Transporter | Strop_2409, Salinispora tropica CNB-440 | 40/60 | ABP54856 |

| KtzA | 381 | Dehydrogenase | FadE20, Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5 | 31/51 | AAY94312 |

| KtzB | 531 | Adenylation domain | NcpB (A domain), Nostoc sp. ATCC 53789 | 38/56 | AAO2334 |

| KtzC | 90 | Thiolation domain | LtxA (T domains), Lyngbya majuscula | 31/53 | AAT12283 |

| KtzD | 321 | Nonheme iron halogenase | SyrB2, Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae | 58/74 | AAD50521 |

| KtzE | 1643 | NRPS (A T E C T) | TioR, Micromonospora sp. ML1 | ≈40/55 module homology | CAJ34374 |

| KtzF | 250 | Thioesterase | RifR, Amycolatopsis mediterranei | 41/55 | AAG52991 |

| KtzG | 1273 | NRPS (A KR T) | CesA, Bacillus cereus | ≈30/50 module homology | ABK00751 |

| KtzH | 5260 | NRPS (C A T E C A(MT) T C A * T E C A T TE) | NRPS, Rhodococcus sp. RHA1 | ≈40/50 module homology | ABG97880 |

| KtzI | 424 | Lysine/Ornithine N-monooxygenase | PvdA, Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 35/55 | AAX16346 |

| KtzJ | 71 | MbtH-like protein | Ecm8, Streptomyces lasaliensis | 74/80 | BAE98157 |

| KtzK | 222 | Regulatory protein | AfsR, Streptomyces coelicolor | 43/55 | BAA14186 |

| KtzL | 340 | SAM-dependent methyltransferase | CalO6, Micromonospora echinospora | 40/55 | AAM70356 |

| KtzM | 396 | Cytochrome P450 | PlaO3, Streptomyces sp. Tu6071 | 41/59 | ABB69748 |

| KtzN | 554 | Adenylation domain | MassB, Pseudomonas fluorescence | 40/54 | ABH06368 |

| KtzO | 323 | Dioxygenase | TlmR3, Streptoalloteichus hindustanus | 44/58 | ABL74947 |

| KtzP | 334 | Dioxygenase | TlmR3, Streptoalloteichus hindustanus | 43/55 | ABL74947 |

| KtzQ | 533 | Flavin-dependent halogenase | ThaL, Streptomyces albogriseolus | 60/75 | ABK79936 |

| KtzR | 505 | Flavin-dependent halogenase | PyrH, Streptomyces rugosporus | 54/69 | AAU95674 |

| KtzS | 174 | Flavin reductase | Pyr9, Streptomyces vitaminophilus | 40/60 | ABO15845 |

| ORF4 | 213 | Regulator | Veis_0716, Verminephrobacter eiseniae | 31/50 | YP_995516 |

| ORF5 | 224 | Thioesterase | BarC, Burkholderia pseudomallei 1710b | 38/53 | ABA52161 |

| ORF6 | 385 | Dehydrogenase | Orf34, Streptomyces vitaminophilus | 48/62 | ABO15870 |

| ORF7 | 635 | RadicalSAM | ThnK, Streptomyces cattleya | 34/51 | CAD18979 |

| ORF8 | 597 | Adenylation domain | LgrC, Brevibacillus parabrevis | 40/59 | Q70LM5 |

| ORF9 | 328 | Ornithine cyclodeaminase | Strop_1041, Salinispora tropica CNB-440 | 43/58 | ABP53515 |

| ORF10 | 240 | Regulator | TioB, Mictromonospora sp. ML1 | 51/71 | CAJ34358 |

Sequence analysis and database comparison allowed us to postulate the following functions (Fig. 2B). Genes ktzA–D are postulated to be involved in the biosynthesis of the remarkable MecPGly moiety. KtzD is highly homologous to mononuclear nonheme iron halogenase proteins (7) and by analogy is believed to chlorinate a terminal methyl group of thioester-bound aliphatic amino acids. A postulated substrate for this enzyme is Ile- (or allo-Ile-) loaded KtzC, which can be generated via activation of Ile (or allo-Ile) by A domain KtzB, followed by tethering of the activated amino acid to the phosphopantetheinyl arm of KtzC. Indeed, bioinformatic analysis of the substrate-binding pocket of KtzB predicts specificity for the activation of branched hydrophobic residues (SI Table 3). We postulate that KtzD-catalyzed chlorination generates δ-chloro-(allo)Ile-S-KtzC, which is subsequently converted to the MecPGly moiety. Unlike the CmaC-catalyzed formation of coronamic acid, biosynthesis of the cyclopropane ring in kutznerides requires intramolecular replacement of the δ-chloride leaving group by Cβ, rather than thioester-stabilized Cα-carbanion (12). We postulate that this role can be fulfilled by acyl-CoA dehydrogenase-like protein KtzA. In analogy to the requirement of CoA thioester-bound substrates for Cα-H acidification in fatty acid dehydrogenation (21), abstraction of the α-proton from δ-chloro-(allo-)Ile-S-KtzC could be facilitated by the phosphopantetheinyl thioester, to be followed by a removal of β-hydride. Similar flavoprotein dehydrogenases catalyze α,β-dehydrogenation of T domain-bound thioesters in the biosynthesis of pyrrole moieties in pyoluteorin and undecylprodigiosin (22, 23). Analogous dehydrogenation of δ-chloro-(allo-)Ile-S-KtzC would yield an enamine intermediate, where Cβ could serve as an intramolecular nucleophile in cyclopropane formation. Final imine reduction would result in the formation of MecPGly, which could subsequently be released from KtzC by the action of a free-standing thioesterase KtzF.

KtzD is followed by a NRPS gene ktzE with five domains (A-T-E-C-T). Predicted adenylation specificity of the KtzE A domain suggests activation of a valine-like amino acid (SI Table 3), in agreement with our postulate that KtzE loads MecPGly to its first T domain. The presence of an epimerization (E) domain within ktzE accounts for the observation that kutznerides contain a d-MecPGly moiety. The next NRPS gene in the cluster, ktzG, suggests that its protein product is responsible for formation of the β-branched α-hydroxy acid monomer. In analogy to other NRPS assembly line modules that carry out hydroxy acid incorporation, this protein consists of three domains: an A domain, a ketoreductase (KR) domain, and a T domain (24, 25). Keto-acid-activating A domains are characterized by the replacement of the α-amino group-stabilizing aspartate, found in amino acid-activating A domains, by a neutral residue, commonly valine (13, 24, 25), as found in KtzG (SI Table 3). Therefore, we postulate that KtzG(A) activates 2-ketoisovaleric acid or 3,3-dimethyl-2-ketobutyrate. The activation is followed by in situ reduction from NADH via KR action to form the hydroxy acid residue. Alternatively, the t-butyl group could arise from KtzL-catalyzed methyl transfer to Cβ of KtzG(T)-tethered 2-ketoisovaleric acid before its reduction by the KR, similar to the formation of 3-methyl glutamate in the biosynthesis of calcium-dependent antibiotic (26).

Formation of the oxoester linkage between the first two residues in kutznerides is likely catalyzed by the C domain within KtzE, condensing MecPGly loaded onto the upstream T domain of KtzE with the hydroxy acid acceptor attached to KtzG(T), thus bypassing the second T domain of KtzE. Subsequent incorporation of the remaining four amino acid residues (piperazate3-O-Me-Ser4-3-OH-Glu5-diClPIC6) and their condensation with the starting depsi-dipeptidyl unit are likely to be catalyzed by KtzH, a four-module NRPS protein. Biosynthesis of kutznerides requires formation and incorporation of the piperazic acid moiety into the growing depsipeptide chain. Although little is known about the biosynthesis of this heterocyclic amino acid containing an unusual hydrazo linkage, feeding experiments showed that glutamic acid and glutamine are precursors to piperazate moieties of monamycin (27) and polyoxypeptin (28). In analogy to the formation of hydrazo linkage in valanimycin (29, 30), N–N bond formation in piperazate biosynthesis is likely achieved by initial N-hydroxylation of the terminal amine of an ornithine-like precursor by flavin monooxygenase KtzI, followed by the intramolecular displacement of hydroxide by α-amine as a nucleophile. γ,δ-Dehydropiperazate (Fig. 2C) could serve as a common precursor to all four piperazate moieties in kutznerides. Enamine to imine tautomerization could provide Cδ–N unsaturated dehydropiperazate. Subsequent reduction of hydrazone moiety would lead to the generation of piperazate. Formation of γ-chloro-substituted piperazate would require initial halogenation of the electron-rich Cγ in γ,δ-dehydropiperazate by KtzQ or KtzR, homologs to known flavin-dependent halogenases (4, 18), followed by the reduction of hydrazone (Fig. 2C). Finally, γ-hydroxylated dehydropiperazate of kutzneride 6 could result from flavin monooxygenase-catalyzed hydroxylation of γ,δ-dehydropiperazate or nonheme iron dioxygenase-catalyzed hydroxylation of Cδ–N unsaturated dehydropiperazate. A similar route for the formation of γ-chloro and γ-hydroxy-substituted piperazic acids has been proposed for the synthesis of piperazimycins (31). We postulate that piperazate monomers are incorporated into the assembly line by the action of the first A domain of KtzH.

The second adenylation domain of KtzH contains an embedded methyltransferase (MT), similar to the A domain within pyochelin synthetase in pyochelin biosynthesis (32). Based on the presence of a MT and the predicted A domain serine specificity (SI Table 3), we postulate that the second module of KtzH incorporates O-methyl serine as the fourth residue in the growing chain. The third module of this protein is expected to carry out incorporation of glutamate. At ≈90 residues, this module's A domain, designated A*, is only 20% the size of other A domains and is likely to be nonfunctional, suggesting that glutamate activation and loading may be carried out in trans by the action of free-standing KtzN. The Cγ hydroxylation of Glu5 is likely to be catalyzed by either of the mononuclear nonheme iron dioxygenases KtzO or KtzP (33). Perhaps one oxygenase generates the threo and the other the erythro diastereomer of 3-OH-Glu5 found in different kutznerides. The E domain in the proposed glutamate-loading module agrees with the observed d-configuration of this residue. Finally, incorporation of 6,7-dichlorotryptophan, likely biosynthesized by double halogenation of tryptophan by a flavin halogenase (KtzQ or KtzR), is carried out by the final A domain of KtzH acting as the sixth and last module of the assembly line. Macrocyclization and release of the hexadepsipeptide from the assembly line are catalyzed by the thioesterase that is the final domain of KtzH (20). Postassembly line epoxidation of the indole ring and cyclization to form the tricyclic hexahydropyrroloindole moiety are likely catalyzed by the P450 monooxygenase KtzM, similar to the postulated role of LtxB in lyngbyatoxin biosynthesis (34).

It should be pointed out that no candidate genes for the reduction of the amide moiety of glutamine or Cδ–N double bond of dehydropiperazate and its γ-chloro derivative have been identified in the kutzneride cluster. Similarly, no putative gene for the intramolecular cyclization to form the six-member ring of piperazate scaffold has been detected. Although genes encoding for the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites are usually clustered, incomplete clusters have previously been identified, such as the enterocin and pederin clusters (35, 36).

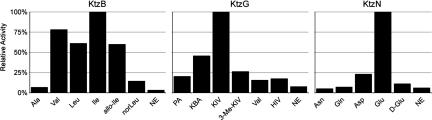

Adenylation Domain Activity Assays.

Adenylation domains are responsible for the selection of building blocks in the biosynthesis of nonribosomal peptides. Analysis of the primary sequence within substrate-binding pockets of these domains allows for the prediction of A domain selectivities (37). The A domains within the kutznerides gene cluster (SI Table 3) have predicted specificities in agreement with the primary structure of kutznerides. To obtain experimental evidence for the proposed specificity of three of the seven adenylation domains, KtzB, KtzN, and KtzG were cloned, overexpressed, and purified from Escherichia coli and their ability to reversibly adenylate various amino acids tested.

KtzB demonstrates a preference for hydrophobic branched amino acids, because l-Ile, l-Val, l-Leu, and l-allo-Ile were preferentially activated in ATP-pyrophosphate assays (PPi) exchange (Fig. 3). The preferential activation of Ile is in agreement with the postulate that KtzD should catalyze halogenation at the substrate δ-methyl group. Adenylation activity of KtzN was also tested, because we postulate that this enzyme loads the T3 domain of KtzH with glutamic or 3-hydroxy-glutamic acid in trans and thus substitutes for the activity of incomplete A* domain in module three of KtzH. Indeed, KtzN demonstrates a preference toward reversible formation of l-Glu-AMP, with modest activation of l-Asp (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Adenylation domain activities of KtzB, KtzG, and KtzN in kutznerides cluster. NE, no enzyme; PA, pyruvic acid; KBA, 2-ketobutyric acid; KIV, 2-ketoisovaleric acid; HIV, 2-hydroxyisovaleric acid. All acids are l, unless otherwise indicated.

Particularly significant is the substrate specificity of the adenylation module of KtzG because of the protein's postulated involvement in the formation of β-branched-α-hydroxy acid monomer. When tested in ATP-PPi exchange assays, KtzG shows a strong preference for activation of keto acids over the cognate amino or hydroxy analogs. α-Ketoisovaleric acid is the preferred substrate of KtzG (Fig. 3). Although moderate activity toward 2-keto-butyric acid was noted, no substantial activation of 3,3-dimethyl-2-ketobutyrate was detected, suggesting that the t-butyl group found in many kutznerides is likely formed via KtzL-catalyzed Cβ methylation of tethered 2-ketoisolaveryl-S-KtzG, before its in situ reduction. The amino acid specificities of these three adenylation domains of KtzB, KtzN, and KtzG provide direct biochemical evidence for the involvement of this gene cluster in the biosynthesis of kutznerides. The remaining four adenylation domains of the NRPS assembly line have not yet been isolable in soluble form.

Our double-halogenase-based cloning approach led to the identification of a 56-kb cluster that sets the stage for deciphering the chemical logic for assembly of the kutzneride class of cyclic hexadepsipeptides. As we anticipated, the kutzneride gene cluster harbors two types of halogenating enzymes. We assigned the mononuclear nonheme iron halogenase KtzD as a cryptic halogenation catalyst in the biosynthesis of methylcyclopropyl-glycine moiety. One of the two flavoprotein halogenases is likely involved in the formation of 6,7-dichloro-hexahydropyrroloindole and the other in the chlorination of piperazate unit. The kutznerides cluster provides a first glimpse into how nature constructs a cyclopropane moiety attached to Cβ of an amino acid. No less interesting are two conformationally constrained nonproteinogenic amino acids: the highly substituted tricyclic hexahydropyrroloindole scaffold and the hydrazo-containing γ-chloropiperazate. The hydroxy acid unit also brings a conformationally restricting dimethyl or trimethyl β substituent to further rigidify the macrocyclic lactone scaffold. Understanding the enzymatic construction of these monomer units is prelude to portability and reengineering efforts to incorporate these building blocks into other natural product assembly lines.

Materials and Methods

Kutzneria DNA Manipulation.

Kutzneria sp. 744 was cultured as described (1), and the total DNA was isolated by using the Qiagen (Valencia, CA) DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit, protocol for Gram-positive bacteria. PCRs were carried out in a final volume of 50 μl by using Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) with genomic DNA as a template and halogenase degenerate primers (SI Table 2). PCR products were ligated into the pCR-BLUNT II- TOPO vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and transformed into TOP10 E. coli electrocompetent cells, and obtained colonies were sequenced [Dana Farber Cancer Institute (Boston, MA) sequencing facility], resulting in the identification of three halogenating enzymes. Three primer sets, specific to each of the three halogenases, were designed based on the resulting sequences (SI Table 2).

Preparation and Screening of Kutzneria's Fosmid Library.

The library was prepared in the fosmid vector pCC2FOS (Epicentre Biotechnologies, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's protocol, with several modifications: the end-repair step was performed after size selection and was followed by two equal-volume phenol/chloroform extractions and buffer exchange to water (CentriSep columns; Princeton Separations, Adelphia, NJ). Inserts were ligated into the vector by using T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs) for 16 h at 4°C. Infected EPI100-T1R cells were grown in liquid gel cultures, prepared in 50 sterile vials containing 1 ml of LB, 5 mg of SeaPrep Agarose (Cambrex, Rockland, ME), and 12.5 μg of chloramphenicol per vial. Vials were grown at 37°C overnight resulting in a growth of ≈60 clones per vial. The vials were subsequently vortexed for 5 sec, and 1 μl of the culture was tested by using all three sets of specific primers. The positive pools were plated on LB/agar/chloramphenicol plates, and 80 colonies were subjected to colony PCR by using the same specific primers. Positive colonies were grown in liquid cultures overnight and induced to a high copy number according to the manufacturer's protocol (Epicentre), and the DNA was isolated by using the Qiagen Miniprep kit, with the following modifications: after the addition of neutralizing buffer, an equal volume of chloroform wash was performed, and DNA was precipitated by the addition of isopropanol (0.7 volumes) and centrifugation (20 min, 10,000 × g). The DNA was washed with 70% aqueous ethanol, air-dried, and resuspended in elution buffer (10 mM Tris·Cl, pH 8.5; Qiagen). DNA sequencing was performed by Agencourt Bioscience (Beverly, MA), and sequence analysis was carried out by BLAST software.

Adenylation Domain Cloning, Expression, and Purification.

DNA fragments corresponding to adenylation domains KtzB and KtzN and A-KR-T protein KtzG were amplified from fosmid DNA via PCR by using Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs). A list of PCR primers and restriction sites is provided in SI Table 4. PCR products were purified by agarose gel electrophoresis, digested with the appropriate restriction enzymes, purified (GFX kit; GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ), and ligated into digested vectors: KtzB into pQE30 derivative (Qiagen), KtzG into pET24b (Novagen, San Diego, CA), and KtzN into pMAL-c2X (New England Biolabs). After transformation into E. coli TOP10 (Invitrogen), expression vectors were purified, and the inserts were confirmed by ddNTP sequencing. Positive clones were subsequently transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3), and resulting transformants were grown in antibiotic-supplemented LB medium (ampicillin for KtzB-pQE30 and KtzN-pMAL-c2X, and kanamycin for KtzG-pET24b). Protein overexpression was carried out by the inoculation of 2 liters of the medium with 20 ml of overnight culture, and cultures were incubated at 35°C, then 25°C, and finally 15°C until OD600 ≈0.6. Overproduction was induced by the addition of 100 μM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) (KtzB, KtzG) or 300 μM IPTG (KtzN), and cultures were incubated for an additional 15 h at 15°C. The resulting N-terminally His-tagged KtzB and C-terminally His-tagged KtzG were purified by Ni-affinity chromatography, whereas KtzN, possessing the N-terminal maltose-binding protein tag, was purified by amylose affinity chromatography (SI Fig. 4). The KtzB and KtzG were dialyzed against 10 mM Tris, pH 8/50 mM sodium chloride/2 mM magnesium chloride/10% glycerol buffer, flash-frozen, and stored at −80°C. KtzN was directly flash-frozen while in the 10 mM maltose/25 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, elution buffer.

ATP-PPi Exchange Assays.

Substrates for the ATP-PPi exchange assay were purchased from Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI) with the exception of trimethylpyruvic acid, which was purchased from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA) as a 60% aqueous solution. Keto and hydroxy acids supplied as the free acids were neutralized with an equimolar amount of NaOH before use. Tetrasodium [32P]PPi was obtained from NEN–PerkinElmer (Boston, MA). ATP-PPi exchange was assayed in 500 μl of reaction buffer (50 mM Tris·HCl/40 mM KCl/10 mM MgCl2, pH 7.5) containing 0.1 mM ATP, 0.5 mM tetrasodium PPi (0.72 μCi of [32P]PPi), 0.1 mM DTT, and 10 mM substrate. Reactions were initiated by adding purified protein to a final concentration of 2 μM. After incubating at 37°C for 10 min, reactions were quenched by the addition of charcoal suspension (0.1 M tetrasodium PPi/0.35 M HClO4/16 g/liter charcoal). Free [32P]PPi was removed by centrifugation of the sample followed by washing twice with wash solution (0.1 M tetrasodium PPi/0.35 M HClO4). Charcoal-bound radioactivity was measured on a Beckman LS 6500 (Fullerton, CA) scintillation counter.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Audrius Menkis and Anders Broberg (Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden) for a generous gift of Kutzneria sp. 744 and Carl J. Balibar for valuable suggestions and careful proofreading of the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants GM-20011 and GM-49338 (to C.T.W.). D.G.F. is supported by the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship (Grant DRG-1893-05). M.S. and M.A.M. are supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

Abbreviations

- MecPGly

2-(1-methylcyclopropyl)-d-glycine

- NRPS

nonribosomal peptide synthetase

- T domain

thiolation domain

- KR

ketoreductase domain

- E domain

epimerization domain

- PPi

pyrophosphate.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the GenBank database (accession no. EU074211).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0708242104/DC1.

References

- 1.Broberg A, Menkis A, Vasiliauskas R. J Nat Prod. 2006;69:97–102. doi: 10.1021/np050378g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pohanka A, Menkis A, Levenfors J, Broberg A. J Nat Prod. 2006;69:1776–1781. doi: 10.1021/np0604331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dorrestein PC, Yeh E, Garneau-Tsodikova S, Kelleher NL, Walsh CT. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:13843–13848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506964102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yeh E, Garneau S, Walsh CT. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:3960–3965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500755102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keller S, Wage T, Hohaus K, Holzer M, Eichhorn E, van Pee KH. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2000;39:2300–2302. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20000703)39:13<2300::aid-anie2300>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yeh E, Blasiak LC, Koglin A, Drennan CL, Walsh CT. Biochemistry. 2007;46:1284–1292. doi: 10.1021/bi0621213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaillancourt FH, Yin J, Walsh CT. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:10111–10116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504412102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galonić DP, Vaillancourt FH, Walsh CT. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:3900–3901. doi: 10.1021/ja060151n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ueki M, Galonić DP, Vaillancourt FH, Garneau-Tsodikova S, Yeh E, Vosburg DA, Schroeder FC, Osada H, Walsh CT. Chem Biol. 2006;13:1183–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galonić DP, Barr EW, Walsh CT, Bollinger JM, Jr, Krebs C. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:113–116. doi: 10.1038/nchembio856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaillancourt FH, Yeh E, Vosburg DA, O'Connor SE, Walsh CT. Nature. 2005;436:1191–1194. doi: 10.1038/nature03797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelly WL, Boyne MT, II, Yeh E, Vosburg DA, Galonić DP, Kelleher NL, Walsh CT. Biochemistry. 2007;46:359–368. doi: 10.1021/bi061930j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang Z, Flatt P, Gerwick WH, Nguyen VA, Willis CL, Sherman DH. Gene. 2002;296:235–247. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00860-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guenzi E, Galli G, Grgurina I, Gross DC, Grandi G. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32857–32863. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanchez C, Butovich IA, Brana AF, Rohr J, Mendez C, Salas JA. Chem Biol. 2002;9:519–531. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nowak-Thompson B, Chaney N, Wing JS, Gould SJ, Loper JE. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2166–2174. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.7.2166-2174.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirner S, Hammer PE, Hill DS, Altmann A, Fischer I, Weislo LJ, Lanahan M, van Pee KH, Ligon JM. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1939–1943. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.7.1939-1943.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zehner S, Kotzsch A, Bister B, Sussmuth RD, Mendez C, Salas JA, van Pee KH. Chem Biol. 2005;12:445–452. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elsaesser R, Paysan J. Biotechniques. 2004;37:200–202. doi: 10.2144/04372BM04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finking R, Marahiel MA. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2004;58:453–488. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghisla S, Thorpe C. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:494–508. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas MG, Burkart MD, Walsh CT. Chem Biol. 2002;9:171–184. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00100-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garneau S, Dorrestein PC, Kelleher NL, Walsh CT. Biochemistry. 2005;44:2770–2780. doi: 10.1021/bi0476329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Magarvey NA, Ehling-Schulz M, Walsh CT. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:10698–10699. doi: 10.1021/ja0640187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishida K, Christiansen G, Yoshida WY, Kurmayer R, Welker M, Valls N, Bonjoch J, Hertweck C, Borner T, Hemscheidt T, Dittmann E. Chem Biol. 2007;14:565–576. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Milne C, Powell A, Jim J, Al Nakeeb M, Smith CP, Micklefield J. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:11250–11259. doi: 10.1021/ja062960c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arroyo V, Hall MJ, Hassall CH, Yamasaki K. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1976:845–846. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Umezawa K, Ikeda Y, Kawase O, Naganawa H, Kondo S. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans. 2001;1:1550–1553. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parry RJ, Li W. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1994:995–996. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tao T, Alemany LB, Parry RJ. Org Lett. 2003;5:1213–1215. doi: 10.1021/ol0340989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller ED, Kauffman CA, Jensen PR, Fenical W. J Org Chem. 2007;72:323–330. doi: 10.1021/jo061064g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reimmann C, Patel HM, Serino L, Barone M, Walsh CT, Haas D. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:813–820. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.3.813-820.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strieker M, Kopp F, Mahlert C, Essen LO, Marahiel MA. ACS Chem Biol. 2007;2:187–196. doi: 10.1021/cb700012y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edwards DJ, Gerwick WH. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:11432–11433. doi: 10.1021/ja047876g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Piel J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14002–14007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222481399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Piel J, Hertweck C, Shipley PR, Hunt DM, Newman MS, Moore BS. Chem Biol. 2000;7:943–955. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stachelhaus T, Mootz HD, Marahiel MA. Chem Biol. 1999;6:493–505. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.