Abstract

Sexual activity and mating are accompanied by a high level of arousal, whereas anecdotal and experimental evidence demonstrate that sedation and calmness are common phenomena in the postcoital period in humans. These remarkable behavioral consequences of sexual activity contribute to a general feeling of well being, but underlying neurobiological mechanisms are largely unknown. Here, we demonstrate that sexual activity and mating with a receptive female reduce the level of anxiety and increase risk-taking behavior in male rats for several hours. The neuropeptide oxytocin has been shown to exert multiple functions in male and female reproduction, and to play a key role in the regulation of emotionality after its peripheral and central release, respectively. In the present study, we reveal that oxytocin is released within the brain, specifically within the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus, of male rats during mating with a receptive female. Furthermore, blockade of the activated brain oxytocin system by central administration of an oxytocin receptor antagonist immediately after mating prevents the anxiolytic effect of mating, while having no effect in nonmated males. These findings provide direct evidence for an essential role of an activated brain oxytocin system mediating the anxiolytic effect of mating in males.

Keywords: black–white box, elevated plus maze, paraventricular nucleus, risk-taking behavior, anxiety

The neuropeptide oxytocin (OT) is a well acknowledged neuromodulator/neurotransmitter of the brain regulating emotionality, stress coping, and prosocial behaviors (1–3). In females, high activity of the brain OT system has been linked to the fine-tuned regulation of parturition and milk letdown (4), to the performance of maternal behaviors (3), and to the low stress response characteristic for the peripartum period (5, 6). Importantly, behavioral and physiological actions of intracerebral OT are not limited to females, because OT synthesis, local OT release, and OT receptor binding have also been demonstrated in the male brain (2, 7, 8). A major site of both OT synthesis and release within the brain is the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) (2), a region integrating behavioral and neuroendocrine stress responses (9). In male rats and mice, OT is an important regulator of sexual function (10), of anxiety (11), and of stress-coping circuitries (12–14). Moreover, in humans, intranasal OT was recently described to promote trust (15), and to reduce the level of anxiety (16), possibly at the level of the amygdala (17). With respect to sexual activity, preclinical (18) and human (19) research has shown elevated OT secretion into the blood during mating behavior and orgasm, respectively. Additionally, increased OT levels have been described in the cerebrospinal fluid after mating in rats (20), which is indicative of stimulation of the OT system (21).

In combination, these findings lead us to hypothesize that mating results in reduced anxiety-related behavior, possibly mediated by an elevation in local OT release within the brain, specifically within the PVN. Therefore, after providing evidence for the anxiolytic effect of mating in males, intracerebral microdialysis was performed within the PVN of conscious male rats in the presence of either a nonreceptive (nonprimed; nonmated group) or a receptive (estrogen/progesterone-primed; mated group) female. Moreover, the causal involvement of brain OT in the reduced anxiety-related behavior found after copulation was examined by using a selective OT receptor antagonist administered immediately after mating.

Results

Effects of Mating on Anxiety in Males.

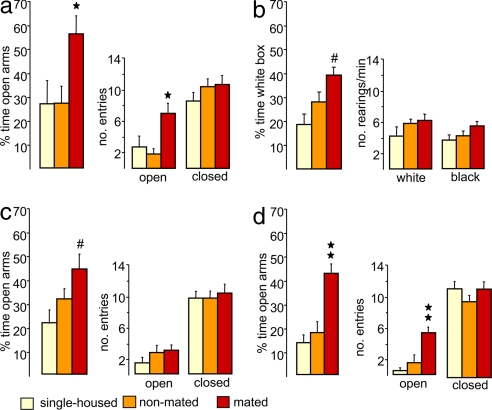

Male Wistar rats, which were successfully mated with a receptive female for 30 min during the dark phase, showed significantly reduced anxiety-related behavior, both on the elevated plus maze (22) (Fig. 1a) and in the black–white box (23) (Fig. 1b), 30 min after removal of the female rat. Males that were mated spent a higher percentage of time in the unprotected and exposed open arms of the plus maze (factor mating, F(2,25) = 3.62, P = 0.042, ANOVA) and entered the open arms more often (F(2,25) = 6.72, P = 0.005) compared with single-housed and nonmated males (P < 0.05, Bonferroni's test). In confirmation, in the black–white box, mated males spent a higher percentage of time (F(2,25) = 6.70, P = 0.005) in the aversive lit compartment compared with the single-housed group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1b). The anxiolytic effect of mating was found to be a long-lasting and robust phenomenon, because increased risk-taking behavior on the plus maze could be confirmed both after 120 min (P < 0.05 versus single-housed) (Fig. 1c) and 240 min (P < 0.001 versus single-housed and nonmated controls) (Fig. 1d) after mating. Moreover, an anxiolytic effect of mating was also seen, when the rats were mated in the light phase (i.e., 6–8 h after lights on) [supporting information (SI) Fig. 4a]. However, the level of anxiety found after mating did not correlate with the number of intromissions (SI Fig. 4b). Sexual activity did not significantly alter the locomotor activity and exploratory behavior after 30, 120, and 240 min, because the number of entries into the closed arms of the maze (24) and the frequency of rearings displayed in the white or black box (23), respectively, were similar among groups (Fig. 1 a–d).

Fig. 1.

Anxiolytic effect of mating in males. Male Wistar rats were tested on the elevated plus maze (a, c, and d) and in the black–white box (b) 30 min (a and b), 120 min (c), and 240 min (d) after termination of a 30-min mating period. Male rats were either single-housed (yellow) or exposed to a nonreceptive (nonmated group; orange) or an estrogen/progesterone-primed (mated group; red) female rat in their home cage in the dark phase. Reduced anxiety levels were found in mated males at all three time points as indicated by increased exploration of the open arms of the plus maze (a, c, and d) and of the lit compartment of the black–white box (b), respectively. The locomotor activity (number of entries into the closed arms of the plus maze) (a, c, and d) was not altered by mating. Data represent means + SEM. Group size was as follows: single-housed: a, n = 8; b, n = 8; c, n = 12; d, n = 9; nonmated: a, n = 13; b, n = 9; c, n = 11; d, n = 10; mated: a, n = 7; b, n = 11; c, n = 10; d, n = 11. ★★, P < 0.001; ★, P < 0.05 versus single-housed and nonmated males; #, P < 0.05 versus single-housed males after ANOVA.

In a subsequent experiment, which has been performed because OT release already started to rise during the presence of the primed female (Fig. 2, dialysates 3 and 4), the anxiety-related behavior on the elevated plus maze was compared between males, which were either single-housed (n = 9) or exposed to a primed female behind a perforated polycarbon wall (n = 9). Statistical analysis revealed no differences in anxiety-related behavior between these two groups 30 min after removal of the female (percentage of entries into open arms: single-housed, 34.0 ± 2.8%; presence of primed female, 36.9 ± 4.0%; F(1,16) = 0.36; P = 0.56; percentage of time on open arms: 13.5 ± 2.6 versus 14.2 ± 3.6%; F(1,16) = 2.64; P = 0.86) or in the locomotor activity (number of entries into closed arms, 10.9 ± 1.5 versus 10.8 ± 1.5).

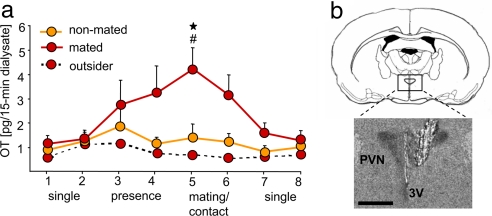

Fig. 2.

OT release within the brain during sexual activity in male rats. Mating triggers OT release into the extracellular fluid of the hypothalamic PVN of male Wistar rats as indicated by elevated OT content in microdialysates sampled during exposure to a receptive female (a). Two 15-min microdialysates were sampled during single-housing (dialysates 1 and 2), during the presence of a nonreceptive (nonmated group, orange; n = 5) or receptive (mated group, red; n = 8) female behind a perforated wall (dialysates 3 and 4), during physical contact (nonmated) or mating with the respective female (dialysates 5 and 6), and after removal of the female from the male's home cage (dialysates 7 and 8). The dotted line (red symbols) indicates OT content in microdialysates sampled from outside the PVN of a mated male (see also SI Fig. 5). Note the tendency of elevated OT release in males in the presence of the receptive female (dialysates 3 and 4; mated group). Data represent means + SEM. ★, P < 0.05 versus single-housing (dialysates 1, 2, 7, and 8); #, P < 0.05 versus nonmated group. (b) Schematic drawing of the rat brain at the level of the hypothalamus and the PVN (Upper) (at bregma −1.5 mm) (40) and microphotograph of a Nissl-stained coronal brain section after removal of the microdialysis probe located inside the right PVN (Lower). 3V, third ventricle. (Scale bar, 1.0 mm.)

Monitoring of OT Release in the PVN of Male Rats During Mating.

In the next stage, we wanted to demonstrate that activation of brain OT because of sexual activity is likely to enforce these behavioral adaptations. Thus, to link the brain OT system with mating-induced anxiolysis, the dynamics of neuronal OT release was monitored within the PVN via intracerebral microdialysis. Fifteen-minute microdialysates were collected from male rats in their home cage during single housing, in the presence of the receptive (mated group) or nonreceptive (nonmated group) female behind a perforated wall, as well as during and after a 30-min mating period. A significant change in OT release within the PVN across the eight samples was found (factor time: F(7,91) = 3.0, P = 0.007), which depended on the presence of either the receptive or the nonreceptive female rat (factor mating: F(1,13) = 6.88, P = 0.021) (Fig. 2a). It is important to note that even the presence of a receptive female behind the perforated wall tended to elevate the intra-PVN release of OT in the male rat (Fig. 2a, dialysates 3 and 4). Therefore, auditory, visual, and/or olfactory stimuli originating from a receptive female are likely to contribute to the activation of the brain OT system in preparation for the anticipated sexual activity. However, significant activation of local OT release within the PVN was witnessed only during successful mating (P < 0.05 versus single-housing and versus nonprimed group; dialysate 5). In contrast, OT release was unchanged in males, which were in contact with a nonreceptive female (Fig. 2a, nonmated group). The microdialysis procedure per se did not affect mating behavior, because the number of intromissions (14.0 ± 3.68) was not different than that of nonoperated rats (13.2 ± 1.52). The mating-induced release of OT was locally restricted to the PVN as revealed by unchanged concentration in samples collected from outside the PVN (Fig. 2a and SI Fig. 5).

Administration of an OT or a Vasopressin Receptor Antagonist.

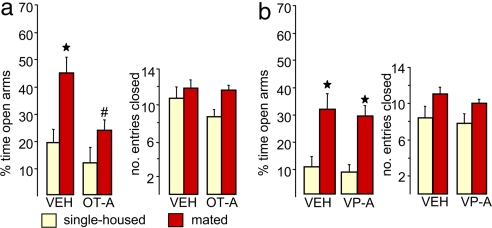

The demonstration of a significant release of OT within the male brain in response to mating consequently led us to determine whether there is a causal link between mating-induced activation of the brain OT system and the subsequent anxiolysis. Therefore, the widely distributed brain OT receptors (7) of mated male rats were blocked by administration of a selective OT receptor antagonist into the lateral ventricle via a previously implanted guide cannula. The antagonist treatment was performed immediately after removal of the receptive female from the male's cage to prevent adverse effects on penile erection and thereby sexual activity (10). Confirming our hypothesis, the reduced level of anxiety-related behavior seen in vehicle-treated males on the plus maze 30 min after mating (two-way ANOVA, factor mating: F(1,27) = 12.0, P = 0.022, compared with the respective single-housed group) was prevented by the OT receptor antagonist (factor treatment: F(1,27) = 9.13, P = 0.036; Fig. 3a; compared with the vehicle-treated mated males). This effect was neuropeptide specific, because in an additional group of male rats, administration of the receptor antagonist for the related neuropeptide vasopressin had no effect on mating-induced anxiolysis (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, OT receptor antagonist administration had no effect on anxiety-related behavior in nonmated rats, which further proves that the up-regulation of the OT-system is responsible for the anxiolytic effect of mating.

Fig. 3.

Brain OT mediates the anxiolytic effect of sexual activity. Male rats were infused with a selective OT receptor antagonist (OT-A) (0.75 μg/5 μl) (a) or a vasopressin receptor antagonist (VP-A) (0.75 μg/5 μl) (b) into the right cerebral ventricle immediately after a 30-min mating period with a receptive female rat. Treatment with the OT-A, but not the VP-A, prevented the reduced anxiety-related behavior seen in vehicle (VEH)-treated mated males compared with VEH-treated single-housed male rats on the plus maze. The percentage of time spent in the open arms of the maze indicates anxiety-related behavior, and the number of entries performed into the closed arms indicates the locomotor activity. Data represent means + SEM. Group size was as follows: single-housed (yellow): vehicle, n = 7 (a), n = 11 (b); OT-A, n = 8; VP-A, n = 5; mated (red): VEH, n = 8 (a), n = 11 (b); OT-A, n = 8; VP-A, n = 6. ★, P < 0.01 versus respective single-housed group; #, P < 0.05 versus VEH-treated mated group.

Discussion

These results provide evidence that an elevated activity of the brain OT system, as a consequence of sexual activity, mediates the anxiolytic effect of successful mating in males. Thus, increased release of OT, as demonstrated within the PVN, is important not only for the regulation of sexual functions (10) but also for supporting future beneficial behavioral strategies. Multiple behavioral consequences of reduced anxiety are possible, which are likely to be species dependent. In rats, the most beneficial behavioral strategy for a male is to embrace the risky search for novel mating partners to ensure optimal distribution of his genes, especially in sparsely populated environments (25). Also, OT has been shown to exert reinforcing and rewarding actions (26). Therefore, the combination of these behavioral traits of increased OT after successful mating in the polygamous male rodent may facilitate the potentially risky search for receptive females (25), increasing the chances for distribution of his genes. In addition, the activated brain OT system has also been linked to a general attenuation of stress responsiveness (5, 6, 16, 17, 27), and brain OT was shown to promote non-rapid eye movement sleep (28). Therefore, the phenomenon of increased relaxation, calmness, and sedation found in humans after sexual activity and orgasm (29, 30), which are clearly related to anxiolysis, may also be mediated by an activated OT system. Moreover, although highly speculative, the possibility exists that enforced/reinforced trust to the sexual partner involves brain OT (15, 26). However, the dominant behavioral trait from the wide range of possible OT effects in the postcoital period may depend on natural environmental conditions and the species considered (31).

The question arises via which brain circuitries OT exerts the anxiolytic effects after mating. The demonstration of mating-induced release of OT within the PVN points toward the possibility of direct OT effects within the PVN (13, 27), a brain region integrating inputs from other stress-related brain sites and regulating anxiety (9, 27, 32). Also, we may consider OT diffusion to remote regions (2) after local release in the PVN, as well as mating-induced OT release from axonal terminals originating within the PVN and projecting to other brain sites, such as the amygdala. Here, OT was shown to exert anxiolytic effects, to inhibit autonomic fear responses (12) and to promote sedation (14). Moreover, the activation of the amygdala was reduced after intranasal OT treatment (17), and after ejaculation in men (33), further implicating similar anxiolytic mechanisms of OT actions across species. Thus, multiple brain regions relevant for OT actions might be involved in the anxiolytic effects seen after mating in male rats. This may also partially explain the fact that a rather transient increase in local OT release results in a behavioral effect that lasts over several hours. Additionally, the role of other neurotransmitter systems, including serotonin, dopamine, and opioids all activated during sexual activity (10, 34, 35), and their regulation by OT needs to be considered.

The maintenance of emotional homeostasis including the regulation of a well balanced level of anxiety is a key function of limbic brain regions, which developed early in evolutionary terms. Brain OT, which is conserved throughout numerous species (36), has been demonstrated to be a vital component of this circuitry. Our results demonstrate that sexual activity and mating behavior activate OT release within the male brain. In turn, the activated OT system contributes to reduced emotional responses to anxiogenic stimuli, which could be an important neurobiological mechanism supporting the positive effects of sexual activity on mental and physical health. In parallel, the increased risk-taking behavior found after copulation is likely to have evolved as an important behavioral strategy in male polygamous mammals to secure the successful distribution of their genes. Thus, our findings may further our neurobiological understanding of behavioral and emotional consequences of sexual activity, and the important involvement of brain OT.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

Sexually naive adult male (body weight, 350–400 g) and female (200–250 g) Wistar rats (Charles River, Bad Sulzfeld, Germany) were used. They were kept under standard laboratory conditions (12:12 light/dark cycle, lights off at noon; 22°C; 60% humidity; food and water ad libitum). Female rats were ovariectomized under isoflurane anesthesia at least 3 weeks before the experiments, and were s.c. treated with estrogen (200 μg/0.2 ml of oil) and progesterone (500 μg/0.2 ml of oil; Fluka Chemie, Buchs, Switzerland) 48 and 6 h before start of the mating experiment, respectively, to increase sexual receptivity. Nonprimed female rats received 0.2 ml of oil. All experiments were approved by the local Bavarian government and performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals by the National Institutes of Health.

Experimental Design.

Effects of mating on anxiety in males.

Single-housed male rats were divided into the following three groups: single-housed males, males with a nonreceptive female, and males with an estrogen/progesterone-primed, receptive female. During the 30-min presentation of the respective female in the male's home cage, the number and frequency of mounts with intromissions were recorded.

Males were tested on the elevated plus maze or in the black–white box 30, 120, or 240 min after removal of the female. Mating experiments were performed in the dark between 1400 and 1700 (i.e., 2–5 h after lights off). In a second set of male rats, mating effects on anxiety were confirmed during the light phase (i.e., 6–8 h after lights on) (see SI Fig. 4).

In an additional experiment, an estrogen/progesterone-primed, receptive female was placed into the male's cage behind a perforated polycarbon wall allowing auditory, visual, and olfactory communication, but no physical contact for 30 min; males were tested on the plus maze after 30 min and compared with single-housed controls.

Monitoring of OT release in the PVN of male rats during mating.

Two days after stereotaxic surgery (14) (see SI Text), eight consecutive 15-min dialysates were collected: samples 1 and 2 were taken under basal, single-housed conditions; samples 3 and 4 were collected in the presence of a receptive or nonreceptive female behind a perforated wall allowing sensory communication, but no physical contact. Afterward, the wall was removed allowing sexual behavior (mated group) or physical contact (nonmated group) during collection of samples 5 and 6, before the respective female was removed and collection of samples 7 and 8. OT content in lyophilized microdialysates was quantified by RIA (37) (see SI Text).

Administration of an OT or a vasopressin receptor antagonist.

To test the involvement of endogenous OT in the anxiolytic effect of mating, a selective OT receptor antagonist, desGly-NH2(9),d(CH2)5[Tyr(Me)2,Thr4]OVT (0.75 μg/5 μl) (38), or vehicle (sterile isotonic saline) were slowly infused into the lateral ventricle of the male rat (see SI Text). Infusions were performed after termination of the 30-min mating period and removal of the receptive female to avoid interference with sexual functions (39). Thirty minutes after intracerebroventricular treatment, the anxiety-related behavior of mated male rats was tested on the plus maze. In a second experiment performed under otherwise identical conditions, a vasopressin V1a receptor antagonist d(CH2)5Tyr(Me)vasopressin (0.75 μg/5 μl) (38) or vehicle were infused.

Elevated plus maze.

Anxiety-related behavior was tested on the elevated plus maze (6, 22). Increased open-arm exploration (percentage of time spent on and number of entries performed into open arms; 140 lux) indicates reduced anxiety. The number of entries into closed arms (20 lux) monitored during the 5-min observation period indicates locomotor activity (24).

Black–white box.

To confirm the anxiolytic effect of mating in another established test for anxiety-related behavior, rats were monitored in the black–white box (23) (lit compartment: 40 × 50 cm, 350 lux; dark compartment: 40 × 30 cm, 70 lux) 30 min after mating. The percentage of time spent in the lit compartment indicates anxiety-related behavior; the number of rearings is recorded as exploratory behavior (23).

Statistics.

Data are presented as mean + SEM. Either a one-way ANOVA (factor mating: single-housed, contact without or with mating; factor treatment) or a two-way ANOVA (factors, treatment × time; or factors, mating × treatment) was performed. All interactions were followed up by Bonferroni's post hoc tests for pairwise comparisons. Significance was accepted at P < 0.05. All statistics were performed by using SPSS 13.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Landgraf for quantification of OT in dialysates and M. Manning (University of Toledo Health Science Campus, Toledo, OH) for providing the OT and VP receptor antagonists.

Abbreviations

- OT

oxytocin

- PVN

paraventricular nucleus.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0705860104/DC1.

References

- 1.Choleris E, Little SR, Mong JA, Puram SV, Langer R, Pfaff DW. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:4670–4675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700670104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landgraf R, Neumann ID. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2004;25:150–176. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Insel TR, Young LJ. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:129–136. doi: 10.1038/35053579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russell JA, Leng G, Douglas AJ. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2003;24:27–61. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3022(02)00104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Windle RJ, Shanks N, Lightman SL, Ingram CD. Endocrinology. 1997;138:2829–2834. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.7.5255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neumann ID, Torner L, Wigger A. Neuroscience. 2000;95:567–575. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00433-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gimpl G, Fahrenholz F. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:629–683. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ludwig M, Pittman QJ. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:255–261. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herman JP, Cullinan WE. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:78–84. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)10069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Argiolas A, Melis MR. Physiol Behav. 2004;83:309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ring RH, Malberg JE, Potestio L, Ping J, Boikess S, Luo B, Schechter LE, Rizzo S, Rahman Z, Rosenzweig-Lipson S. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;185:218–225. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0293-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huber D, Veinante P, Stoop R. Science. 2005;308:245–248. doi: 10.1126/science.1105636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neumann ID, Wigger A, Torner L, Holsboer F, Landgraf R. J Neuroendocrinol. 2000;12:235–243. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2000.00442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ebner K, Bosch OJ, Kromer SA, Singewald N, Neumann ID. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:223–230. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kosfeld M, Heinrichs M, Zak PJ, Fischbacher U, Fehr E. Nature. 2005;435:673–676. doi: 10.1038/nature03701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heinrichs M, Baumgartner T, Kirschbaum C, Ehlert U. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:1389–1398. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00465-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirsch P, Esslinger C, Chen Q, Mier D, Lis S, Siddhanti S, Gruppe H, Mattay VS, Gallhofer B, Meyer-Lindenberg A. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11489–11493. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3984-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stoneham MD, Everitt BJ, Hansen S, Lightman SL, Todd K. J Endocrinol. 1985;107:97–106. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1070097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carmichael MS, Humbert R, Dixen J, Palmisano G, Greenleaf W, Davidson JM. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1987;64:27–31. doi: 10.1210/jcem-64-1-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hughes AM, Everitt BJ, Lightman SL, Todd K. Brain Res. 1987;414:133–137. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91333-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Witt DM, Insel TR. J Neuroendocrinol. 1994;6:13–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1994.tb00549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pellow S, Chopin P, File SE, Briley M. J Neurosci Methods. 1985;14:149–167. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(85)90031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henniger MS, Ohl F, Holter SM, Weissenbacher P, Toschi N, Lorscher P, Wigger A, Spanagel R, Landgraf R. Behav Brain Res. 2000;111:153–163. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00151-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korte SM, De Boer SF, Bohus B. Stress. 1999;3:27–40. doi: 10.3109/10253899909001110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robitaille JA, Bovet J. Biol Behav. 1976;1:289–308. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liberzon I, Trujillo KA, Akil H, Young EA. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1997;17:353–359. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Windle RJ, Kershaw YM, Shanks N, Wood SA, Lightman SL, Ingram CD. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2974–2982. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3432-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lancel M, Kromer S, Neumann ID. Regul Pept. 2003;114:145–152. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(03)00118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brody S. Biol Psychol. 2006;71:214–222. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kruger TH, Haake P, Hartmann U, Schedlowski M, Exton MS. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2002;26:31–44. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(01)00036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pfaus JG, Kippin TE, Coria-Avila G. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2003;14:1–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li HY, Ericsson A, Sawchenko PE. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2359–2364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holstege G, Georgiadis JR, Paans AM, Meiners LC, van der Graaf FH, Reinders AA. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9185–9193. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-27-09185.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pfaus JG. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1999;9:751–758. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(99)00034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Devidze N, Lee AW, Zhou J, Pfaff DW. Physiol Behav. 2006;88:283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Acher R, Chauvet J, Chauvet MT. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995;395:615–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Landgraf R, Neumann I, Holsboer F, Pittman QJ. Eur J Neurosci. 1995;7:592–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb00663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manning M, Sawyer WH. J Lab Clin Med. 1989;114:617–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Melis MR, Spano MS, Succu S, Argiolas A. Neurosci Lett. 1999;265:171–174. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00236-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Sydney: Academic; 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.