Abstract

Background and Aims

Patients recovering from mild acute pancreatitis typically receive a clear liquid diet (CLD) when ready to initiate oral nutrition. Patient discharge then depends upon successful advancement to solid food. We hypothesized that initiating oral nutrition with a low-fat solid diet (LFSD) after mild pancreatitis would be well-tolerated and would result in a shorter length of hospitalization (LOH).

Methods

Patients with mild pancreatitis were randomized to a CLD or LFSD when ready to resume oral nutrition. Decisions about diet advancement and hospital discharge were at the discretion of the medical team without input from study team members. Patients were monitored daily for recurrence of pain, need to stop feeding, post-refeeding LOH (primary endpoint), and for 28 days post-refeeding to capture readmission rates.

Results

We randomized 121 patients: 66 to CLD, 55 to LFSD. The number of patients requiring cessation of feeding due to pain or nausea was similar in both groups (6% for CLD, 11% for LFSD; p=0.51). The median LOH after refeeding was identical in both groups (1 day, inter-quartile range 1–2; p=0.77). Patients in the LFSD arm consumed significantly more calories and grams of fat than those in the CLD arm during their first meal and on study day #1. There was no difference in 28 day re-admission rates between the two arms.

Conclusions

Initiating oral nutrition after mild acute pancreatitis with a LFSD appeared safe and provided more calories than a CLD, but did not result in a shorter LOH.

INTRODUCTION

Acute pancreatitis results in excess of 240,000 hospitalizations in the U.S. each year and the incidence continues to rise.1–3 The majority of cases are classified as mild and 70% to 90% usually resolve within three to five days.4, 5 The management of mild pancreatitis typically involves intravenous hydration, pain management, and elimination of oral feeding (NPO) until pain has significantly improved. The rationale for keeping patients NPO is based upon the presumption that pancreatic stimulation caused by eating may increase pancreatic inflammation.6 However, the timing and method of resumption of oral feeding after mild acute pancreatitis is based upon anecdotal experience rather than scientific study.7

When the signs and symptoms of acute pancreatitis resolve, patients are typically placed on a clear liquid diet. If this diet is tolerated (e.g., there is no recurrence of pain or vomiting) the patient’s diet is expanded to full liquids or low-fat solids. Discharge is then predicated upon tolerance of a low-fat solid diet.8 It is not known whether resumption of feeding with a liquid diet is essential. Therefore, this sequence may needlessly prolong patient hospitalization, inconvenience patients and their families, and incur unnecessary costs.

We hypothesized that patients recovering from mild acute pancreatitis would be discharged sooner if they resumed feeding with a low-fat solid diet as compared to a clear liquid diet. Implicit in this hypothesis was the assumption that the low-fat solid diet would not cause an excessive number of patients to suffer increased pain or nausea compared to a clear liquid diet. The present study was designed to address these hypotheses.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This was a prospective, randomized, single-center clinical trial authorized by the Institutional Review Board of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Potential subjects were identified by a daily review of inpatient laboratory values in the hospital’s electronic medical records system. Any non-pregnant inpatient aged ≥18 years, with an elevated serum amylase or lipase and a clinical picture consistent with acute pancreatitis (e.g. characteristic abdominal pain lasting ≥24 hours) was screened for the following inclusion criteria:

Amylase and/or lipase >3x the upper limit of normal or >2x the upper limit of normal and a CT scan demonstrating unequivocal acute pancreatitis with peri-pancreatic inflammation (a Balthazar-Ranson score ≥C).9

Mild acute pancreatitis (absence of pancreatic necrosis if an abdominal CT scan was obtained with intravenous contrast and absence of organ dysfunction at any time after hospital admission including hypoxemia [oxygen saturation <90%], hypotension [systolic blood pressure <90mmHg], and renal insufficiency [creatinine >2mg/dl without pre-existing renal disease]).

Ability to be contacted by phone after hospital discharge.

Leukocyte count <16,000/mm and temperature <101.6 degrees Fahrenheit on the day of study enrollment.

Patients were excluded from enrollment if they:

Received any enteral nutrition prior to randomization;

Received parenteral narcotics for abdominal pain <6 hours prior to randomization;

Were considered likely to have poor oral intake or prolonged hospitalization for reasons other than pancreatitis (e.g. severe comorbidities, a pre-existing problem with oral feeding such as gastroparesis, or a likely surgical intervention during the hospital admission);

Had a pancreatic neoplasm;

Were under the direct care of a study team member, enrolled in another pancreas-related clinical trial, or enrolled previously in this study.

Patients meeting preliminary study criteria were consented for the study and monitored daily by a study nurse until the medical team caring for the patient decided to resume oral feeding. At that time, final inclusion/exclusion criteria were verified and patients were randomly assigned to receive either a clear liquid diet (CLD; 588 calories, 2gm of fat/day) or a low-fat solid diet (LFSD; 1200 calories, 35g of fat/day). Randomization was accomplished with the use of a random number generator with dietary assignments placed in numbered opaque envelopes by personnel otherwise uninvolved with the study. Envelopes were opened by a study nurse at the time a diet order was written to reveal the study assignment and to begin non-blinded enrollment in the trial. Once enrolled, all patients were permitted to consume water and extra juice administered by the nursing staff when requested. Those in the LFSD arm were also permitted low-fat snacks (e.g., low-fat custard) if requested. Decisions about diet advancement and the timing of hospital discharge were at the discretion of the medical team without input from study team members. Patients were monitored daily until discharge by a study nurse who recorded dietary and clinical information including diet tolerance and pain scores using a 10-point Likert-type scale. A dietician conducted a calorie count for the first meal and any subsequent meals on study day one. For example, if the first meal was lunch, then lunch and dinner were included in the calorie count for day 1. After hospital discharge, patients were contacted by telephone 28 days after resumption of feeding to inquire about a recurrence of pancreatitis or need for repeat hospitalization.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of the study was the length of hospitalization (LOH) from the time of refeeding until discharge. Secondary outcomes included the frequency that subjects were made NPO because of pain, nausea or vomiting after refeeding, and the need for hospital readmission within 28 days of refeeding.

Sample Size

The median duration of hospitalization for mild pancreatitis in our institution historically has been five days with a typical range of three to ten days. A sample size of 120 total patients was calculated as required to detect a reduction in duration of stay of one day (i.e. to a median of four days), with 90% power and a two-sided α of 0.05.

Statistical Methods

Study outcomes were evaluated with an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis and a per-protocol (PP) analysis. For the ITT analysis, we analyzed all subjects according to their assigned study arm, regardless of any protocol deviations. For the PP analysis, we excluded any subject with a major deviation from protocol defined as having received a diet for first meal other than what had been assigned by randomization; having been permitted to eat within six hours of receiving parenteral narcotics for abdominal pain; or having been enrolled previously in the study.

The post-refeeding LOH was compared between the two study arms using a Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test. The proportions of patients in each arm requiring cessation of diet post-refeeding or requiring hospital readmission were compared using Chi-square analysis or Fisher’s Exact test where appropriate. In an exploratory analysis, univariate odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were calculated by Exact methods to identify variables potentially related to cessation of feeding due to pain, nausea or vomiting after study enrollment. Such variables included age, gender, body mass index, etiology of pancreatitis, number of prior episodes of pancreatitis, abdominal pain scores at time of randomization, serum lipase levels on the day of refeeding and APACHE II10 scores at hospital admission and on study day #1. The APACHE II score on the day of feeding was the highest score generated using appropriate data within a 24 hour window around the time of refeeding. Other variables compared between study arms included the time between randomization and consumption of first meal, number of calories consumed in the first meal and on study day #1, number of grams of fat consumed in the first meal and on study day #1, and the number of meals consumed on study day #1 (e.g., one, two, or three meals). When values of continuous variables were not normally distributed, results are presented as medians with inter-quartile ranges (IQR). All calculations were performed using SAS, version 8.02 (SAS institute, Cary, NC) and two-sided p values <0.05 were considered significant.

Data Safety Monitoring Committee

A data safety monitoring committee (DSMC) comprised of an independent gastroenterologist from another institution and a biostatistician (MDH) was established prior to trial inception. The committee reviewed study data when approximately one-third and two-thirds of the planned accrual had been completed. If there was evidence that the LFSD had clinically inferior effects, the committee would have recommended early termination of the study. Evidence of inferiority was defined a priori as a difference in the proportion of subjects stopping the LFSD which was significant with a p value <0.0l, or a difference in the duration of post-refeeding LOH or readmission rates significant with a p value <0.05. As very strong evidence of a beneficial effect of the LFSD would likely be necessary to alter clinical practice, it was felt unnecessary to stop the trial early if there had been preliminary evidence of such a beneficial effect.

RESULTS

Outcome of Randomization

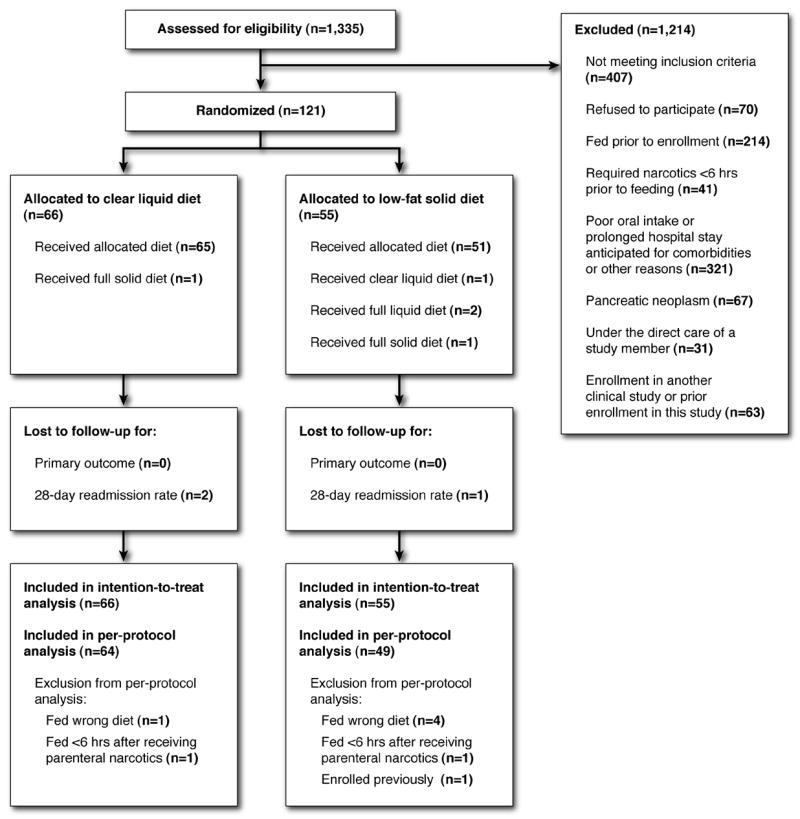

There were 1,335 non-pregnant, adult patients with acute pancreatitis assessed for eligibility based upon an elevation of amylase and/or lipase between May 2, 1999 and September 29, 2005. Among those, 407 failed to meet inclusion criteria, mainly because their pancreatic enzymes were <3x the upper limit of normal with a normal CT scan (when obtained) or they demonstrated evidence of severe pancreatitis (organ dysfunction and/or pancreatic necrosis). Another 807 were excluded for a variety of reasons as shown in Figure 1. There were 121 patients enrolled, including three with enzyme elevations between two to three times the upper limit of normal but with a Balthazar-Ranson score of ≥C based upon CT scan findings. Among the 121 patients enrolled, 66 were randomized to CLD and 55 to LFSD. All 121 were included in the ITT analysis (Figure 1). There were five subjects who received the wrong diet for their first meal (one subject in each arm received a full solid diet, one subject in the LFSD arm received a CLD, and two subjects in the LFSD arm received a full liquid diet). These five subjects were excluded from the PP analysis. There were two subjects who were fed within six hours of receiving parenteral narcotics for abdominal pain (one in each study arm) and both were excluded from the PP analysis. Finally, one subject in the LFSD arm was inadvertently enrolled in the study on two separate hospitalizations (randomized each time to LFSD). Only his first enrollment was included in the PP analysis. Three patients were inadvertently randomized within six hours of receiving parenteral narcotics, but did not actually eat their first meal until six hours or more after receiving narcotics. This was considered a minor protocol violation and these three patients were included in the PP analysis.

FIGURE 1.

The progress of patients through the trial according to CONSORT (consolidated standards of reporting trials) guidelines.22

Characteristics of Participants

Table 1 provides the baseline characteristics of study participants. Subjects in each arm were similar with respect to age, gender, body mass index, etiology of pancreatitis, type of pancreatitis (e.g. acute vs. acute-on-chronic), number of prior episodes of pancreatitis, and pain scores at the time of randomization. The APACHE II scores appeared higher for subjects in the LFSD arm both at admission and on study day #1, with 16 LFSD subjects (29%) having a score ≥8 on study day #1 compared to 6 CLD subjects (9%; p=0.005)

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Participants

| Characteristic | Clear Liquid Diet (n=66) | Low-fat Solid Diet (n=55) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (SD) | 47 (16) | 51 (15) |

| Male (%) | 34 (52) | 23 (41) |

| Mean BMI (SD) | 29 (8) | 29 (6) |

| Etiology of Pancreatitis (%) | ||

| Gallstones | 15 (22.7) | 15 (27.3) |

| Alcohol | 19 (28.8) | 14 (25.4) |

| ERCP | 10 (15.1) | 9 (16.4) |

| Medication | 1 (1.5) | 5 (9.1) |

| Other | 3 (4.6) | 3 (5.4) |

| Unknown | 18 (27.3) | 9 (16.4) |

| Type of Pancreatitis (%) | ||

| Acute | 63 (95.4) | 52 (94.5) |

| Acute-on-chronic | 3 (4.6) | 3 (5.5) |

| Median number of prior episodes of pancreatitis (IQR) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) |

| Median pain score at time of randomization (IQR)* | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) |

| Median APACHE II score on admission (IQR) | 5 (3–7) | 6 (5–9) |

| Median APACHE II score on day of refeeding (IQR) | 4 (2–6) | 6 (4–8) |

BMI = body mass index; IQR = inter-quartile range

Pain scores were based on a 10-point Likert-type scale (10 = maximal pain)

Calorie Count Data

The time intervals between hospital admission and randomization and between randomization and consumption of first meal were similar in both groups (Table 2). By hospital day 3, 81% (98/121) of subjects had received their first meal. The number of subjects who consumed breakfast, lunch, or dinner as their first meal was similar between the two arms, as was the total number of meals consumed on study day one. Full dietary data on calories and grams of fat consumed was available for 64% of first meals and 58% of study day #1 totals (Table 2). Patients randomized to LFSD consumed significantly more calories and grams of fat in both their first meal and for study day #1 overall compared to patients randomized to CLD (p<0.001 for all comparisons).

Table 2.

Dietary Information [Data presented as medians (IQR) and number of subjects for whom data were available]

| Dietary Factor | Clear Liquid Diet (n=66) | Low-fat Solid Diet (n=55) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time (days) between hospital admission and randomization | 2 (1–3) n=66 | 2 (1–3) n=55 | 0.99 |

| Time (hrs) between randomization and first meal | 1 (1–2) n=65 | 2 (1–3) n=55 | 0.36 |

| Total number of meals consumed per patient on study day 1 | 2 (1–2) n=66 | 2 (1–2) n=55 | 0.71 |

| Calories consumed with first meal | 157 (114–207) n=45 | 350 (165–469) n=36 | <0.001 |

| Fat (g) consumed with first meal | 1 (0–1) n=42 | 5 (2–11) n=35 | <0.001 |

| Calories consumed on study day 1 | 301 (233–544) n=45 | 622 (442–827) n=32 | <0.001 |

| Fat (g) consumed on study day 1 | 2 (1–4) n=39 | 13 (6–21) n=31 | <0.001 |

IQR = Inter-quartile range

Diet Tolerance and Adverse Events

A total of 21 patients were made NPO following resumption of feeding (Table 3). Only 10 of these subjects were made NPO because of pain, nausea or vomiting (6% of CLD subjects; 11% of LFSD subjects; p=0.51). The remainder were made NPO for other reasons, primarily impending radiographic or endoscopic procedures. Neither diet was associated with an increased rate of feeding cessation in the PP analysis, although the total numbers were smaller (Table 3). Besides those patients who failed to tolerate their assigned diet, there were no adverse events due to the study and the DSMC did not request early cessation of the trial.

Table 3.

Trial Outcomes

| Outcome | Intention-to-treat Analysis | Per-protocol Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clear Liquids (n=66) | Low-fat Solid Diet (n=55) | P value | Clear Liquids (n=64) | Low-fat Solid Diet (n=49) | P value | |

| Cessation of feeding | ||||||

| Stopped due to pain or nausea/vomiting | 4 (6%) | 6 (11%) | 0.51 | 3 (5%) | 3 (6%) | 1.00 |

| Stopped for other reasons | 8 (12%) | 5 (9%) | 0.59 | 8 (13%) | 4 (8%) | 0.55 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) post-refeeding* | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 0.77 | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 0.54 |

| 28 day readmission rate† | ||||||

| Readmitted for Pancreatitis | 6 (9%) | 3 (6%) | 0.51 | 6 (10%) | 2 (4%) | 0.46 |

| Readmitted for other Reasons | 3 (5%) | 4 (7%) | 0.70 | 3 (5%) | 4 (8%) | 0.70 |

Presented as medians (inter-quartile range).

28 day readmission rates are based on 118 subjects for whom data were available.

We also calculated univariate odds ratios for variables potentially associated with failure of refeeding. Given the limited number of patients made NPO because of pain or nausea after resumption of a diet (n=10) we did not conduct multivariate analyses. Only the abdominal pain score on the day of refeeding (available for 119 patients) was significantly associated with a failure of oral intake, with those experiencing more pain having a higher likelihood of being made NPO (O.R. 1.86; 95% CI 1.22–2.94; p=0.003). Among patients with an abdominal pain score ≤3, 4/108 (4%) failed refeeding, compared to 5/11 (45%) with a score >3 (p<0.001). Other variables examined, but not significantly associated with a failure of oral intake, included age; gender; BMI; etiology of pancreatitis; number of prior episodes of pancreatitis; APACHE II scores at hospital admission and on the day of refeeding; duration of pain prior to refeeding; number of meals consumed on study day 1; temperature, leukocyte count, and serum lipase on study day 1; and study arm assignment.

Length of Hospitalization Post-refeeding (Primary Outcome)

There was no difference in the LOH after resumption of feeding between the two diets according to the ITT analysis (Table 3). The median post-refeeding LOH was 1 day for both CLD and LFSD (IQR 1–2; range 1–9 for both). Measured in hours, the median post-refeeding LOH was 29.5 hours (IQR 25–49) for CLD and 28 hours (IQR 23–49) for LFSD (p=.61). The corresponding mean post-refeeding LOHs were 1.68 (SD 1.85) and 1.71 (SD 2.04) days for the CLD and LFSD arms respectively (p=0.94). The difference in mean post-refeeding LOH was therefore 0.03 days, with a 95% CI of −0.67 to 0.73 days.

The median post-refeeding LOH was identical in the PP analysis (Table 3) and when the analysis was restricted to participants for whom first meal calorie counts were available (data not shown). The total length of hospitalization from hospital presentation to discharge was likewise similar for patients in each study arm by both ITT and PP analyses (median 4 days, IQR 3–5 for CLD; median 4 days, IQR 3–6 for LFSD by ITT; p=0.72).

The median post-refeeding LOH was significantly shorter for the 100 patients who tolerated refeeding compared to the 10 patients who were made NPO because of pain or nausea (1 day, IQR 1-1 vs 7 days, IQR 3–7; p<0.001). However, there was no difference in the post-refeeding LOH between the two diets in an analysis stratified by diet tolerance. In this case, when either the CLD or the LFSD was tolerated, the post-refeeding LOH was 1 day (IQR 1-1; p=0.46). Likewise, when either diet was not tolerated, the post-refeeding LOH was similar (CLD 7 days, IQR 5–8 vs LFSD 5 days, IQR 3–7; p=0.50). Similar findings were also observed using hours instead of days as the outcome (data not shown).

Hospital Readmission Rate

Twenty-eight day follow-up was available for 118 subjects: 64 (97%) CLD and 54 (98%) LFSD. Among these, 16 patients were readmitted to the hospital within 28-days after resumption of feeding; 9 with pancreatitis and 7 for other reasons. There were three subjects lost to follow-up for this endpoint and they were excluded from the readmission rate analyses. Readmission rates were not significantly different for subjects in each diet arm by either ITT or PP analyses (Table 3). By ITT, 6 (9%) of CLD subjects were readmitted with pancreatitis compared to 3 (6%) of LFSD subjects (p=.51). Of note, 14 of the 16 subjects who required hospital readmission had alcohol-induced pancreatitis as their cause for initial admission.

DISCUSSION

Recent practice-management guidelines have presented information regarding appropriate timing of refeeding and forms of nutrition in severe acute pancreatitis.11–13 However, little attention has been paid to optimizing the dietary management of mild pancreatitis, although this form represents the overwhelming majority of cases. Many clinicians recommend resumption of oral feeding of patients with mild disease when abdominal tenderness improves and appetite returns.7, 8 Traditionally, patients resume feeding with a clear liquid diet, although some clinicians advocate use of small, low-fat meals of carbohydrates and proteins with a gradual increase in quantity over 3–6 days as tolerated.8,14 Even a recently convened panel of gastroenterologists, pancreatologists, intensive care specialists, and nutritionists acknowledged the paucity of clinical trial data with which to make evidence-based decisions about choice of diet in this setting.14 In fact, many of the principal medical texts relied upon by house officers and hospitalists fail to make any recommendations about how to resume feeding patients recovering from mild acute pancreatitis.4, 15–18

We hypothesized that patients recovering from mild acute pancreatitis would be discharged from the hospital sooner if they resumed oral nutrition with a LFSD as compared to a CLD. This was not the case, as both diets were associated with an identical post-refeeding LOH by both ITT and PP analyses. The median post-refeeding LOH was one day for both diets while the mean post-refeeding LOH was 1.7 days for both diets. The 95% confidence interval for the difference in means was −0.67 to 0.73 days, indicating that the true difference in post-refeeding LOH is very unlikely to exceed three-quarters of a day in either direction. We feel this excludes any clinically meaningful difference in outcome.

Implicit in our hypothesis was the assumption that a LFSD would not cause an excess number of patients to suffer pain and nausea compared to a CLD. Indeed, comparing the LFSD to a CLD, there was no significant difference in the proportion of patients failing to tolerate oral feeding, suggesting this practice was safe. However, our study was designed to compare LOH and was powered to detect an improvement of one day. To improve the precision in estimating the true difference in LOH from +/− 0.7 days to +/− 0.5 days, our study would have required approximately 250 patients. A well-powered non-inferiority study would need to be larger still in order to show that a LFSD does not increase LOH by more than 0.5 days.

It is not clear why a decreased LOH was not realized by bypassing a step in the reintroduction of oral feeding. A prolonged delay before refeeding might have diminished the chance for achieving a shortened LOH, but 81% of our patients were fed within 3 days of hospitalization, suggesting we did not wait an excessive amount of time before refeeding. Our median post-refeeding LOH was only 1 day, and this may have been too short to detect a reduction in stay because of physician behavior. In other words, physicians may keep patients in the hospital for a full day after initiating diet regardless of how well patients tolerate that diet. In this context, our study provides evidence that a CLD and LFSD are both acceptable choices as they yield similar clinical outcomes after mild pancreatitis.

Our finding is consistent with two prior studies that compared a CLD to a regular solid diet as the first meal after abdominal surgery.19, 20 In both studies, with a combined population of 486 patients, the LOH was not shortened despite the regular diet being tolerated as well as a CLD. The authors did not offer explanations for this finding, other than the possibility that discharge was delayed at one hospital (a Veterans’ Administration medical center) for social reasons.19 It is possible that physicians make discharge decisions based not only on a patient’s diet tolerance, but also on other factors independent of diet. It is also possible that physicians making discharge decisions in these non-blinded trials extended the hospitalizations to provide additional observation of patients receiving experimental diets.

Failure to tolerate initial feeding was found to be a significant problem affecting 8% of our study population despite their having only mild acute pancreatitis. To our knowledge, ours is the first study to document the rate of diet intolerance among patients with mild pancreatitis. The only prior study to investigate diet intolerance after acute pancreatitis found recurrence of pain after refeeding among 24 of 116 (21%) patients recovering from various severities of pancreatitis, including some with pancreatic necrosis.21 We were careful to exclude patients with organ failure, pancreatic necrosis, and a requirement for parenteral narcotics within 6 hours of refeeding to be sure study subjects were truly ready to resume oral nutrition.

There were 13 patients (11%) who were made NPO after refeeding due to impending radiographic or endoscopic procedures. These procedures were not anticipated at the time of study enrollment, and were simply part of inpatient management as determined by the responsible medical team. We were careful not to exert influence over the team’s management decisions to avoid introducing bias as this was an unblinded study.

In our study, we found an association between increased abdominal pain scores on the day of refeeding and failure to tolerate an oral diet. Because pain was measured on a Likert-type scale, the observed odds ratio of 1.86 suggests that each extra point on the pain scale carries a significant risk for the need to discontinue oral intake. Intolerance of initial refeeding attempts was associated with a significantly longer LOH (median 7 days compared with 1 day when refeeding was tolerated). These results suggest that refeeding should be postponed until patients have only minimal residual abdominal pain.

One potential limitation of our study was the large number of excluded patients. Among those excluded, a large percentage had comorbidities that were considered likely to result in feeding difficulties or prolongation of their hospital stay. We wanted to ensure our primary endpoint (post-refeeding LOH) was a reflection only of the assigned diet, and not of other factors. Because all exclusions were made prior to randomization, patients in both study arms would have been affected equally, preventing the exclusions from introducing significant bias. However, because of these exclusions we acknowledge that our findings may not apply to patients with complex comorbidities or severe pancreatitis, limiting the generalizability of our findings.

We also acknowledge that our primary outcome (post-refeeding LOH) was based upon the subjective discretion of the medical team without predefined objective discharge criteria. We are unaware of validated, objective criteria for either initiation of feeding or hospital discharge after mild pancreatitis. Using our best judgment, we could have imposed a structured set of discharge criteria on the medical teams, but we were concerned this would seriously limit the generalizability of our findings. Different physicians in different practice settings likely apply varying criteria for hospital discharge. We therefore felt our findings would be more generalizable if we left the timing of discharge to the discretion of the medical team. Otherwise, the utility of our findings in real clinical practice (e.g. the clinical effectiveness of the low-fat solid diet) would have remained unknown.

In summary, resumption of feeding after mild acute pancreatitis with a LFSD did not shorten the LOH when compared to a CLD. However, while we failed to resolve the important question of what is the optimal diet for patients recovering from mild pancreatitis, we have identified several positive clinical findings that advance our knowledge. We found that a low-fat solid diet did not appear to cause significant deleterious effects, and may therefore now be considered an option for patients who desire greater dietary choice when initiating feeding after mild pancreatitis. We also found that higher abdominal pain scores on the day of refeeding were associated with a subsequent need to stop feeding, and that failure to tolerate feeding resulted in a significantly longer hospitalization.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Steven D. Freedman for serving on the Data Safety Monitoring Committee. This research was supported in part by an American College of Gastroenterology Clinical Research Award. Dr. Brian C. Jacobson is supported by an NIH/NIDDK career development award (K08 DK070706).

Grant Support: Supported in part by an American College of Gastroenterology Clinical Research Award. Brian C. Jacobson is supported by an NIH career development award (K08 DK070706)

Abbreviations

- CLD

clear liquid diet

- DSMC

data safety monitoring committee

- IQR

inter-quartile range

- ITT

intention-to-treat

- LFSD

low-fat solid diet

- LOH

length of hospitalization

- PP

per-protocol

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Goldacre M, Roberts S. Hospital admission for acute pancreatitis in an English population, 1963–98: database study of incidence and mortality. BMJ. 2004;328:1466–1469. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindkvist B, Appelros S, Manjer J, Borgström A. Trends in incidence of acute pancreatitis in a Swedish population: is there really an increase? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:831–837. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00355-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaheen N, Hansen R, Morgan D, Gangarosa L, Ringel Y, Thiny M, Russo M, Sandler R. The burden of gastrointestinal and liver diseases, 2006. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2128–2138. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steer M. Acute pancreatitis. In: Wolfe M, Davis G, Farraye F, Giannella R, Malagelada J, Steer M, editors. Therapy of Digestive Disorders. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2006. pp. 417–426. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell R, Byrne M, Baillie J. Pancreatitis. Lancet. 2003;361:1447–1455. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13139-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abou-Assi S, O’Keefe S. Nutritional support during acute pancreatitis. Nutrition. 2002;18:938–943. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(02)00991-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lankisch P, Banks P. Pancreatitis. Springer-Verlag; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitcomb D. Acute pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2142–2150. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp054958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balthezar E, Ranson J, Naidich D, Megibow A, Caccavale R, Cooper M. Acute pancreatitis: prognostic value of CT. Radiology. 1985;156:767–772. doi: 10.1148/radiology.156.3.4023241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knaus W, Draper E, Wagner D, Zimmerman J. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.UK Working Party on Acute Pancreatitis. UK guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Gut. 2004;54(Suppl III):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heinrich S, Schäfer M, Rousson V, Clavien P. Evidence-based treatment of acute pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 2006;243:154–168. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000197334.58374.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banks P, Freeman M. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2379–2400. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meier R, Beglinger C, Layer P, Gullo L, Keim V, Laugier R, Friess H, Schweitzer M, Macfie J ESPEN Consensus Group. ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in acute pancreatitis. European Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. Clin Nutr. 2002;21:173–183. doi: 10.1054/clnu.2002.0543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lichtenstein D. Diseases of the pancreas. In: Andreoli T, Carpenter C, Griggs R, Loscalzo J, editors. Cecil Essentials of Medicine. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004. pp. 379–387. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenberger N, Toskes P. Acute and chronic pancreatitis. In: Kasper D, Braunwald E, Fauci A, Hauser S, Longo D, Jameson J, editors. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. New York: McGraw Hill; 2005. pp. 1895–1906. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grendell J. Acute pancreatitis. In: Friedman S, McQuaid K, Grendell J, editors. Current Diagnosis and Treatment in Gastroenterology. New York: Lange Medical/McGraw Hill; 2003. pp. 489–495. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prakash C. Gastrointestinal diseases. In: Green G, Harris I, Lin G, Moylan K, editors. The Washington Manual of Medical Therapeutics. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2004. pp. 349–377. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeffery K, Harkins B, Cresci G, Martindale R. The clear liquid diet is no longer a necessity in the routine postoperative management of surgical patients. Am Surg. 1996;62:167–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pearl M, Frandina M, Mahler L, Valea F, DiSilvestro P, Chalas E. A randomized controlled trial of a regular diet as the first meal in gynecologic oncology patients undergoing intraabdominal surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:230–234. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lévy P, Heresbach D, Pariente E, Boruchowicz A, Delcenserie R, Millat B, Moreau J, Le Bodic L, de Calan L, Barthet M, Sauvanet A, Bernades P. Frequency and risk factors of recurrent pain during refeeding in patients with acute pancreatitis: a multivariate multicentre prospective study of 116 patients. Gut. 1997;40:262–266. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.2.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moher D, Schulz K, Altman D. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. JAMA. 2001;285:1987–1991. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.15.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]