SUMMARY

The trp RNA-binding attenuation protein (TRAP) regulates expression of the tryptophan biosynthetic and transport genes in Bacillus subtilis in response to changes in the levels of intracellular tryptophan. Transcription of the trpEDCFBA operon is controlled by an attenuation mechanism involving two overlapping RNA secondary structures in the 5′ leader region of the trp transcript; TRAP binding promotes formation of a transcription terminator structure that halts transcription prior to the structural genes. TRAP consists of eleven identical subunits and is activated to bind RNA by binding up to eleven molecules of L-tryptophan. The TRAP binding site in the leader region of the trp operon mRNA consists of eleven (G/U)AG repeats. We examined the importance of the rate of TRAP binding to RNA for the transcription attenuation mechanism. We compared the properties of two types of TRAP 11-mers: homo-11-mers composed of eleven wild-type subunits, and hetero-11-mers with only one wild-type subunit and ten mutant subunits defective in binding either RNA or tryptophan. The hetero-11-mers bound RNA with only slightly diminished equilibrium binding affinity but with slower on-rates as compared to WT TRAP. The hetero-11-mers showed significantly decreased ability to induce transcription termination in the trp leader region when examined using an in vitro attenuation system. Together these results indicate that the rate of TRAP binding to RNA is a crucial factor in TRAP’s ability to control attenuation.

Keywords: RNA-binding protein, gene regulation, transcription attenuation, binding kinetics, tryptophan

INTRODUCTION

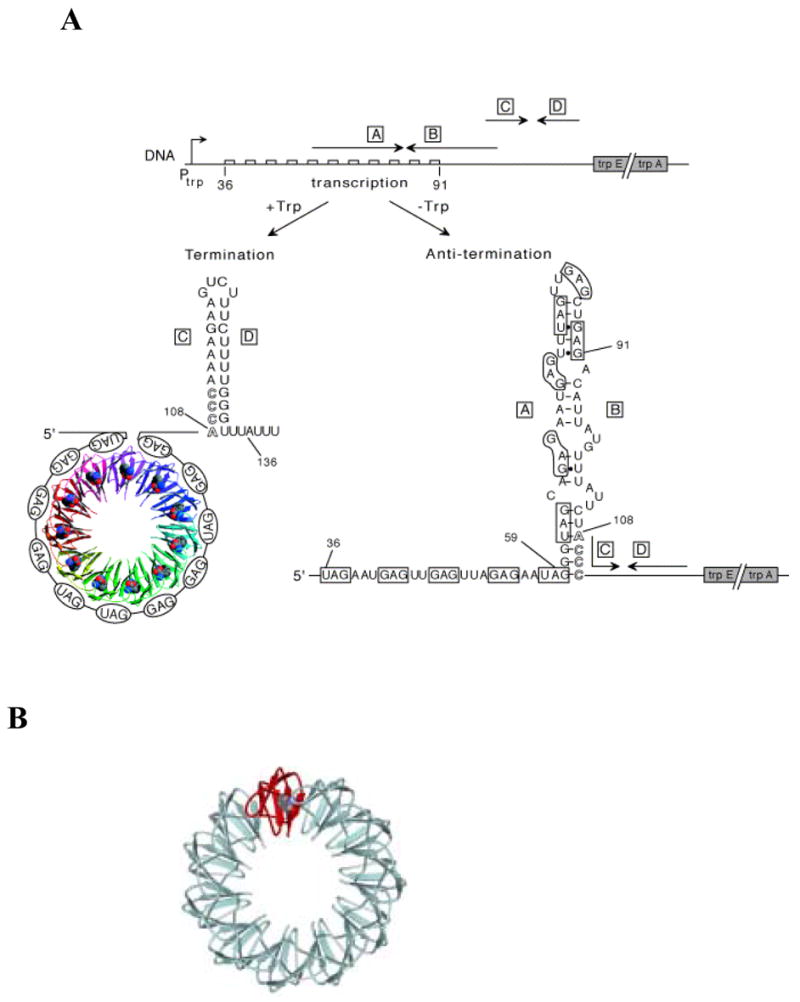

TRAP (trp RNA-binding Attenuation Protein) regulates expression of genes involved in tryptophan biosynthesis and transport in Bacillus subtilis in response to changes in the intracellular concentration of L-tryptophan1–3. Expression of the trpEDCFBA (trp) operon is regulated at both transcriptional and translational levels4. Transcription of the trp operon is regulated by an attenuation mechanism that involves two mutually exclusive RNA secondary structures that can form in the 203 nt untranslated leader region 5′ to trpE (Figure 1). These structures include an intrinsic terminator and an overlapping antiterminator5. TRAP binding to the trp leader region of the nascent trp mRNA inhibits formation of the antiterminator thereby inducing formation of the terminator structure, which halts transcription prior to the structural genes.

Figure 1.

(A) Model of transcription attenuation of the B. subtilis trp operon. The large boxed letters designate the complementary strands of the terminator and antiterminator RNA structures. The TRAP protein is shown as a ribbon diagram with each of the 11 subunits as a different color and the bound tryptophan molecules shown as Van der Waals spheres. The bound RNA is shown wrapping around the TRAP protein. The GAG and UAG repeats involved in TRAP binding are shown in ovals and are also outlined in the sequence of the antiterminator structure. Numbers indicate the residue positions relative to the start of transcription. Nucleotides 108–111 overlap between the antiterminator and terminator structures and are shown as outlined letters. (B). Schematic representation of the (T25A)10WT1 and (R58A)10WT1 hetero-11-mers TRAP used in this study. The wild-type subunit is shown in red and mutant subunits are represented in cyan.

TRAP is composed of 11 identical subunits arranged in a ring-shaped structure and is activated to bind RNA by binding up to 11 molecules of L-tryptophan in pockets formed between adjacent subunits6,7. Tryptophan binding activates TRAP to bind RNA, at least in part, by reducing the flexibility of the protein8. TRAP binding sites contain multiple (up to 11) NAG repeats (N = G ≈ U > A > C) separated by several nonconserved “spacer” nucleotides9,10. Several structures of TRAP complexed with RNAs composed of 11 GAG or 11 UAG repeats show that the bound RNA wraps around the outside of the protein ring with the phosphodiester backbone exposed to the solution9,11,12. The majority of the contacts between the protein and the RNA are to the bases of the AG portion of each (G/U)AG repeat, which interact with Glu36, Lys37, Lys56 and Agr58 of each TRAP subunit7,9,11,12.

In order to cause termination, TRAP must bind and alter the structure of the trp leader transcript before the transcribing RNA polymerase molecule has proceeded beyond the terminator region (Figure 1A). Yakhnin and Babitzke have shown that RNA polymerase (RNAP) pauses in the trp leader region in vitro however, the importance of this pausing on attenuation in vivo is not yet clear13. The kinetics of TRAP binding to RNA are also likely to be important in the transcription attenuation mechanism. To investigate this issue we wished to compare the abilities of TRAP proteins with different kinetic properties of RNA binding to induce transcription termination in the trp leader region. Several mutant TRAP proteins have been identified with reduced affinities for RNA or for tryptophan7. However, since these mutant proteins contain 11 defective subunits, they show drastically reduced affinity for RNA (from ≈ 600-fold decreased to undetectable binding) making them difficult to use to study transcription attenuation. We have developed a method to create hetero-11mers of TRAP composed of various ratios of wild-type (WT) and mutant subunits14,15. Moreover, hetero-11-mers that contain one WT subunit and 10 mutant subunits defective in RNA (or tryptophan) binding have only slightly lower affinity for RNA than wild-type TRAP14,15 and thus provide excellent tools to study TRAP variants with moderately altered binding properties. Here we examined two such hetero-11-mers that contain one WT subunit together with either 10 subunits defective in RNA binding (Arg58 substituted with Ala; R58A)15, or with 10 subunits defective in binding tryptophan (Thr25 substituted with Ala; T25A) and hence are not activated to bind RNA14.

As shown previously14,15, the affinities of both TRAP hetero-11-mers for (GAGAU)11 RNA were only 3–7 fold lower than that of WT TRAP. However, the on-rates for these hetero-11-mers binding to RNA were 12–27 fold less than WT TRAP. Both hetero-11-mers were less effective than WT TRAP at inducing transcription termination in the trp leader region in an in vitro transcription attenuation assay. Decreasing the elongation rate of RNAP by lowering the concentrations of NTPs in the reactions increased the ability of the hetero-11-mers and WT TRAP to induce termination. These studies support the hypothesis that the rate of TRAP binding to RNA is a crucial factor controlling the protein’s ability to participate in attenuation.

RESULTS

Mung Bean nuclease protection studies: Equilibrium binding of TRAP hetero-11-mers

To probe the importance of the kinetics of TRAP binding to RNA in the transcription attenuation mechanism we took advantage of several TRAP hetero-11-mers composed of 1WT subunit and 10 mutant subunits defective in either RNA binding or tryptophan and RNA binding. While the R58A and T25A mutant TRAP proteins show no detectable RNA binding activity7, the presence of just one WT subunit per 11mer dramatically increases the affinity of the (R58A)10WT1 and (T25A)10WT1 hetero-11mers for RNA such that they show only 5–7 fold lower affinity than wild-type TRAP14,15.

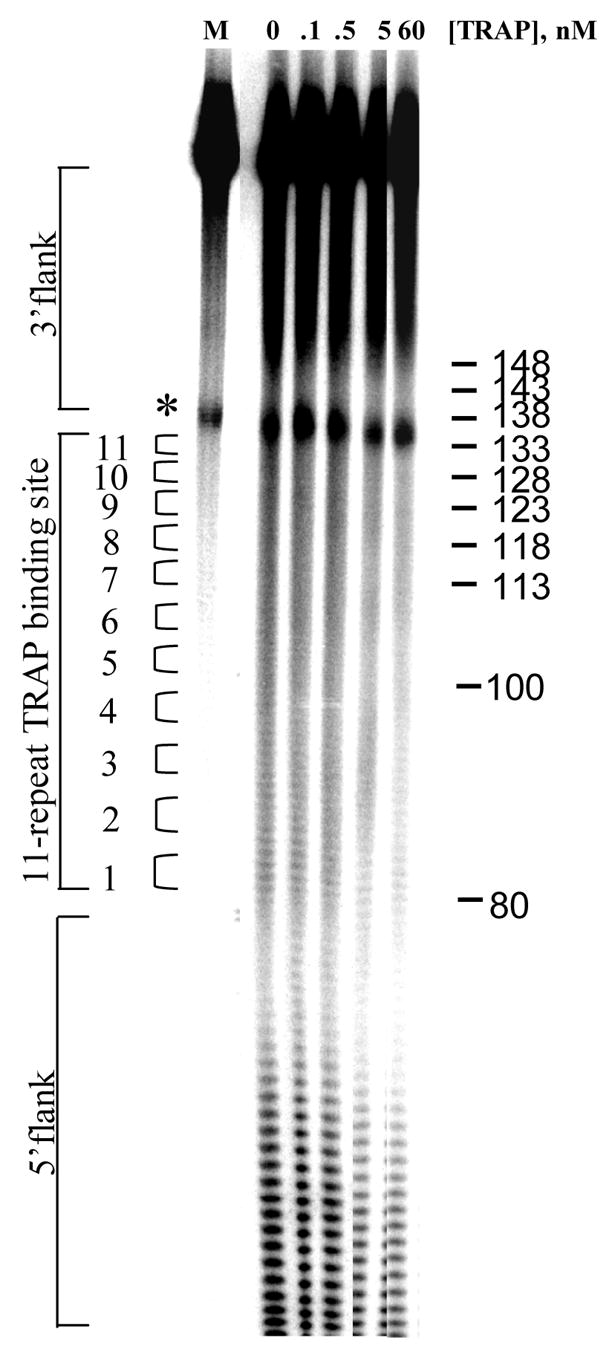

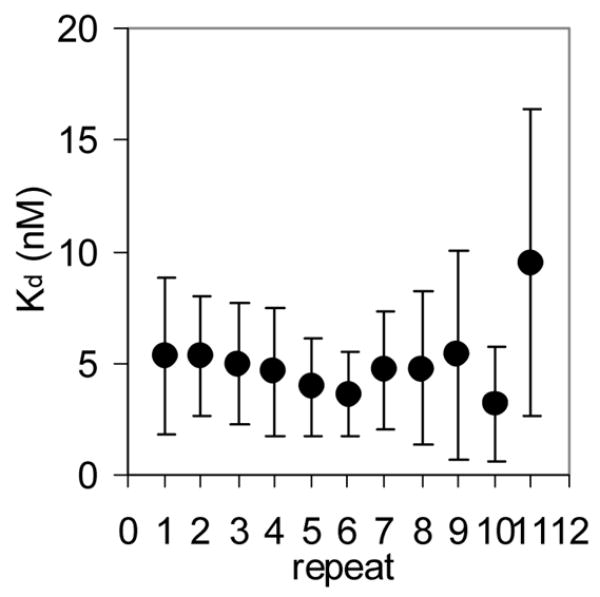

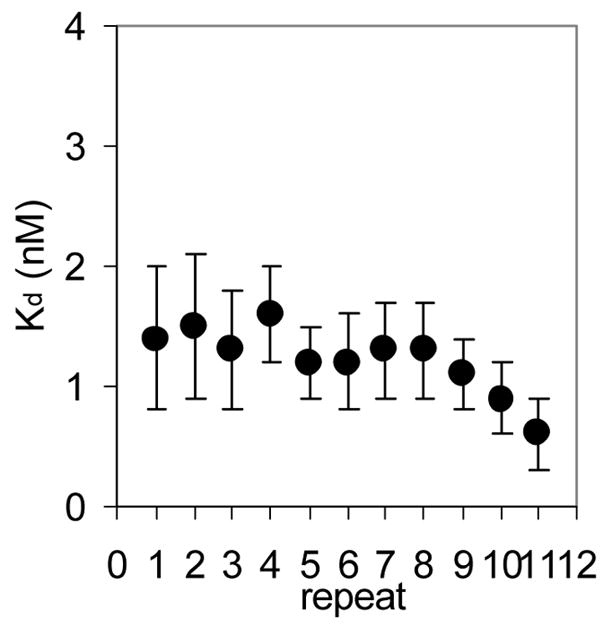

We first characterized the thermodynamic and kinetic properties of these hetero-11-mers in binding to individual repeats within a binding site composed of 11 GAGAU repeats. Mung Bean nuclease (MBN) protection studies under equilibrium conditions have shown that the binding of WT TRAP protects all 11 repeats of (GAGAU)11polyA RNA equally from cleavage and that the affinity of TRAP (Kd ≈ 1.0 nM) does not vary significantly between the repeats16. Here we used this method to examine the binding of the (R58A)10WT1 and (T25A)10WT1 hetero-11-mers to this RNA. MBN cleaves all residues in ssRNA but with slight preferences for A> U>C>G. These preferences are seen in the cleavage pattern of (GAGAU)11polyA RNA in the absence of TRAP. Conditions that yielded relatively uniform digestion of the GAGAU repeats resulted in slight under-digestion of a G-rich segment immediately 5′ to the TRAP binding site (Figure 2A, lane “0”). There is also a short A-rich segment (Figure 2A labeled *) immediately following the TRAP binding site in the 3′ flanking region (residues 135 to 140) that is somewhat cleaved in the absence of nuclease cleavage of these residues, which is likely due to general base hydrolysis (lane M). Adding increasing amounts of (T25A)10WT1 TRAP, which contains 10 mutant subunits defective in binding tryptophan (and RNA) together with one WT subunit, resulted in similar protection of all 11 GAGAU repeats of the TRAP binding site (Figure 2A lanes 0.1 to 60). Slight protection of the underdigested G-rich region immediately 5′ to the binding site was also observed possibly due to TRAP binding altering the structure of this region of the RNA. By examining the fractional protection of the entire binding site as a function of TRAP concentration we derived a binding curve (Figure 2B) and a dissociation constant (Kd) of 6.8 nM (Table 1), which agrees well with the value of 5.3 nM determined by nitrocellulose filter binding14,15. Similar results were obtained with (R58A)10WT1 TRAP (10 mutant subunits defective in binding RNA and one WT subunit), which also protected all 11 GAGAU repeats equally from MBN (data not shown) and yielded a Kd of 5.0 nM (Table 1). This value also agrees well with that of 7.4 nM derived for this interaction by filter binding15. In all cases the affinity of the TRAP proteins for individual GAGAU repeats within the binding site did not vary significantly (Figure 2C–E). As seen previously14,15, neither mutant homo-11-mer protein showed any detectable binding with up to 700 nM protein (Table 1).

Figure 2.

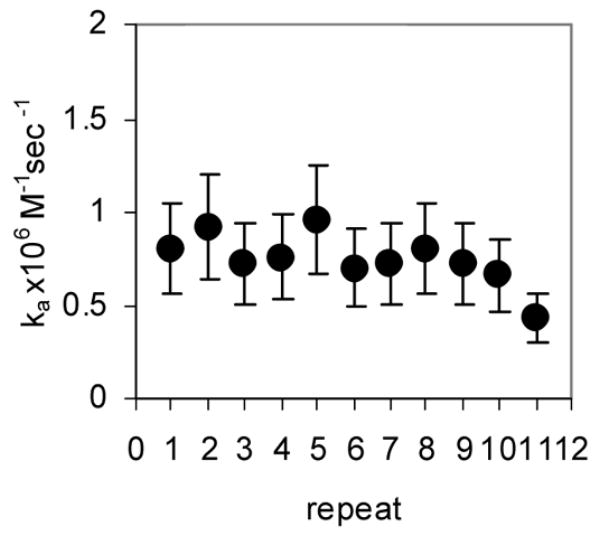

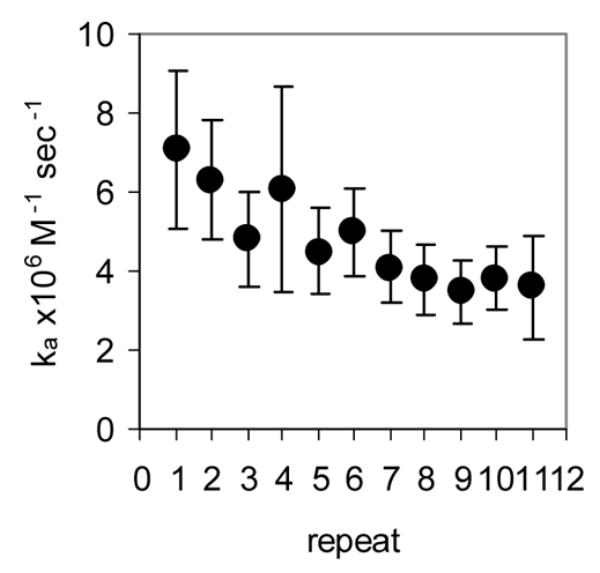

(A) Mung Bean nuclease footprint of (T25A)10WT1 TRAP binding to GAGAU11 RNA (5 pM). The concentration of TRAP was increased from 0 to 60 nM (from the left to the right, lanes marked 0–60). The lane marked “m” is mock-treated control. The position of the TRAP binding site is indicated with a bracket on the left side of the gel with eleven vertical brackets indicating the positions of individual GAG repeats, numbered from the 5′ end. The 5′ flanking and 3′ flanking sequences preceding and following the TRAP binding site are indicated. Positions of MW size markers that were generated by a partial RNase T1 digest of the DNA/RNA chimera “ElevenRiboG”,16 are shown on the right side of the gel. Note that only several representative concentrations of TRAP are shown of the many that were used to generate binding curves (B) Equilibrium binding curve for (T25A)11WT1 hetero-11-mer TRAP binding to (GAGAU)11polyA RNA. Data are the average of seven experiments with standard errors of < 7% of the mean. (C–E) Kd values for TRAP binding to individual repeats numbered 1 to 11 starting at the 5′ most repeat in each binding site in (GAGAU)11polyA RNA determined by protection from Mung Bean nuclease; (T25A)10WT1 TRAP (C), (R58A)10WT TRAP (D), WT TRAP (E). Data for WT TRAP were published previously16 and are shown here for comparison.

Table 1.

Mung Bean nuclease protection analysis of the kinetic parameters of WT TRAP and Hetero-11-mers of TRAP Binding to (GAGAU)11 RNA

| Protein | Kd, nM | ka×106 M−1×sec−1 | kr=Kd×kaa sec−1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | 1.00 ± 0.30 b | 7.00 ± 2.30 b | 7.00×10−3 |

| T25A | NB c | NB c | - |

| (T25A)10WT | 6.80 ± 2.00 | 0.60 ± 0.20 d | 4.08×10−3 |

| R58A | NB c | NB c | - |

| (R58A)10WT | 5.00 ± 3.20 | 0.26 ± 0.12 d | 1.30×10−3 |

Dissociation rate constant (kr) is calculated based on parameters determined in the present study, association rate constant (ka) and averaged dissociation constant Kd (the latter obtained by both filter binding and footprinting).

Data published previously16 and shown here for comparison.

No binding detected up to 500–700 nM TRAP.

Association rate constants are the average of at least six individual experiments using at least three different concentrations of TRAP.

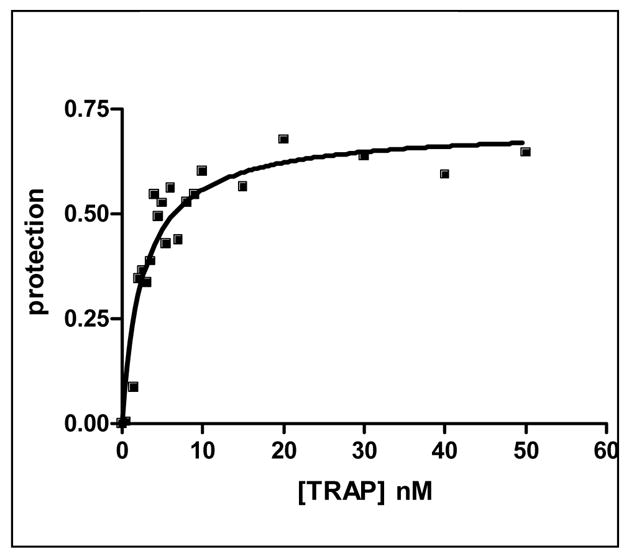

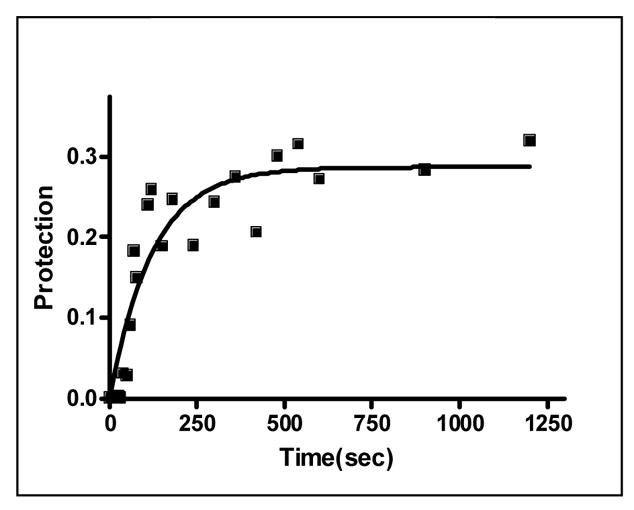

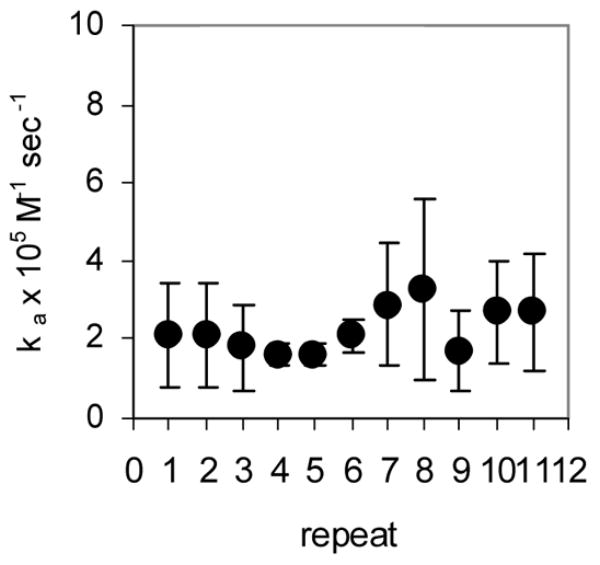

Kinetics of Binding to RNA

Rapid quench MBN protection assays under pre-steady state conditions were used to examine the kinetics of (R58A)10WT1 and (T25A)10WT1 TRAP binding to (GAGAU)11polyA RNA. We have previously used this method to derive an association rate constant (ka) of 7.0 × 106 M−1 sec−1 for WT TRAP binding to this RNA16. As seen in the equilibrium binding studies described above, both hetero-11-mers protected all 11 GAGAU repeats of the binding site (but not the flanking sequences) from nuclease digestion under these conditions (data not shown). By fitting the fractional protection of the binding sites as a function of time (Figure 3A) to Equation 3 (Methods) we obtained observed rate constants (kobs) from which association rate constants (ka) were derived using Equation 4. In each case, kobs was obtained at several different concentrations of protein and found to be directly dependent on the concentration of TRAP in the range studied (data not shown). The values presented in Table 1 are the average of at least six individual experiments using at least three different concentrations of TRAP. The association rate constants (ka) for the (T25A)10WT1 and (R58A)10WT1 hetero-11-mers binding to the entire binding site on the (GAGAU)11polyA RNA were respectively 12- and 27-fold lower than that for WT TRAP (Table 1). In both cases, the ka values did not vary significantly for individual repeats within the binding site (Figure 3B–C), which contrasts our previous finding that WT TRAP bound fastest to repeats at the 5′ end and slowest to those at the 3′ end of the binding site (Figure 3D; See Discussion).

Figure 3.

Kinetic analysis of WT TRAP and hetero-11-mers binding to RNA (A) Kinetic binding curve for (T25A)10WT1 TRAP binding to (GAGAU)11polyA RNA. Data are the average of four experiments with standard errors of < 7% of the mean. Association constants (ka) for (R58A)10WT1 (B), (T25A)10WT1 (C), WT (D) TRAP binding to individual repeats in GAGAU11 RNA. Repeats are numbered 1 to 11 from the 5′ end of the binding site. Data for WT TRAP were published previously16 and are shown here for comparison.

Stopped-flow fluorescence analysis of the kinetics of WT11 TRAP binding to RNA

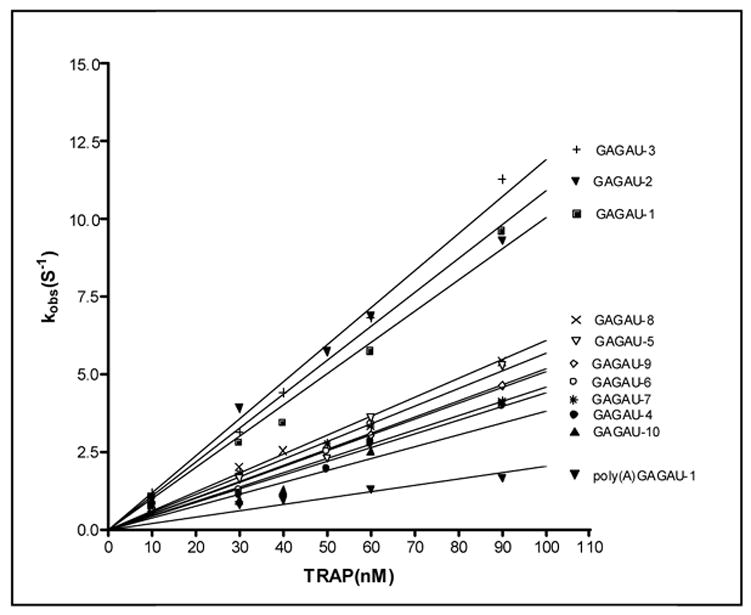

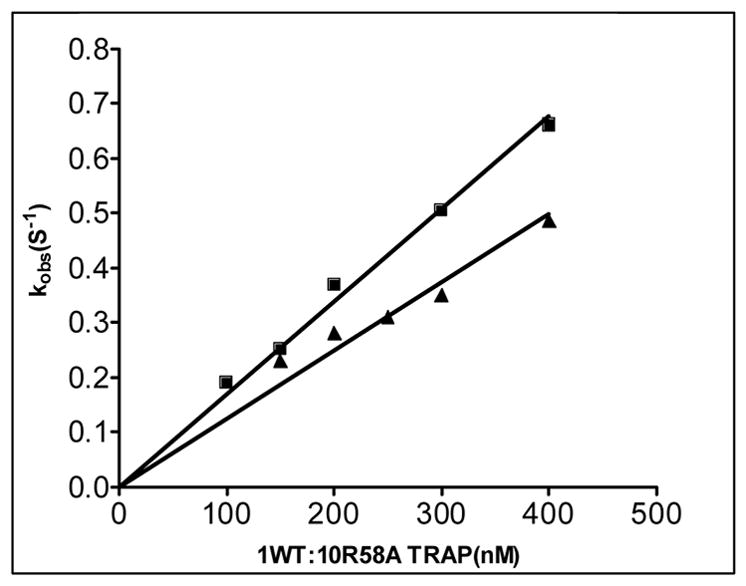

We also used stopped-flow fluorescence to analyze the kinetics of TRAP binding to individual repeats within an 11 repeat RNA site. To do so we examined TRAP binding to several different RNAs that contained 11 GAG repeats separated by two nucleotide spacers. In each case Fluorescein-12-UMP was specifically incorporated into one of the spacer regions between GAG repeats to provide a reporter group from that portion of the binding site. Adding tryptophan-activated TRAP resulted in an increase in the signal from the fluroescein in any of these RNAs (Figure 4A), presumably as a result of the environment of the fluor becoming more hydrophobic when TRAP binds to the RNA. In contrast, TRAP had no effect on the fluorescence when the Fluorescein-12-UMP was placed 5′ to the TRAP binding site in the RNA (Figure 4B). Hence the enhanced fluorescence seen when the fluor is between GAG repeats is indicative of TRAP binding to that region of the binding site. By analyzing the increase in fluorescence with time after adding TRAP, kobs for the interaction of TRAP with various regions of the binding site were determined and from these values, obtained at several different concentrations of TRAP (Figure 4C), ka values for the interaction with these particular repeats were calculated (Table 2). The ka values obtained by this method for WT TRAP binding to an RNA with 10 GAGAA repeats and one GAGAU were approximately 10–17 fold greater than those determined by MBN footprinting for TRAP binding to (GAGUU)1116 (Compare Table 2 to Table 1 and Figure 2E). These differences likely reflect both differences in the two methods used to determine these values as well as differences in the arrangements of the RNAs used for each method. Prior studies have shown that the rate of TRAP binding to its binding site is dependent on the number of residues between the 5′ end of the RNA and the first (G/U)AG repeat of the binding site such that binding is slower when this distance is longer16. The RNAs used here for MBN protection studies contained 70 nts 5′ to the binding site whereas those used in the fluorescence studies had only 2 residues 5′ to the first GAG repeat. Consistent with this proposal, placing 50 nts of nonspecific RNA 5′ to the TRAP binding site in an RNA containing the fluor between the first and second GAG repeats reduced the ka value 5 fold (Table 2) from 100 × 106 M−1 sec−1 to 20 × 106 M−1 sec−1, which is only 3 fold greater than the value obtained for a similar RNA by MBN protection (Tables 1 and 2).

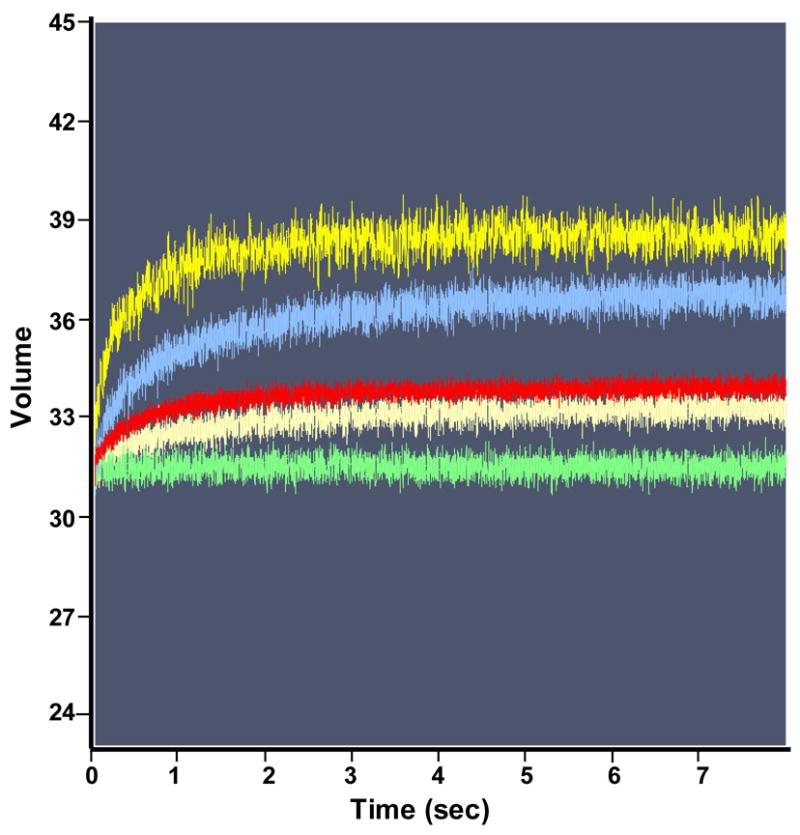

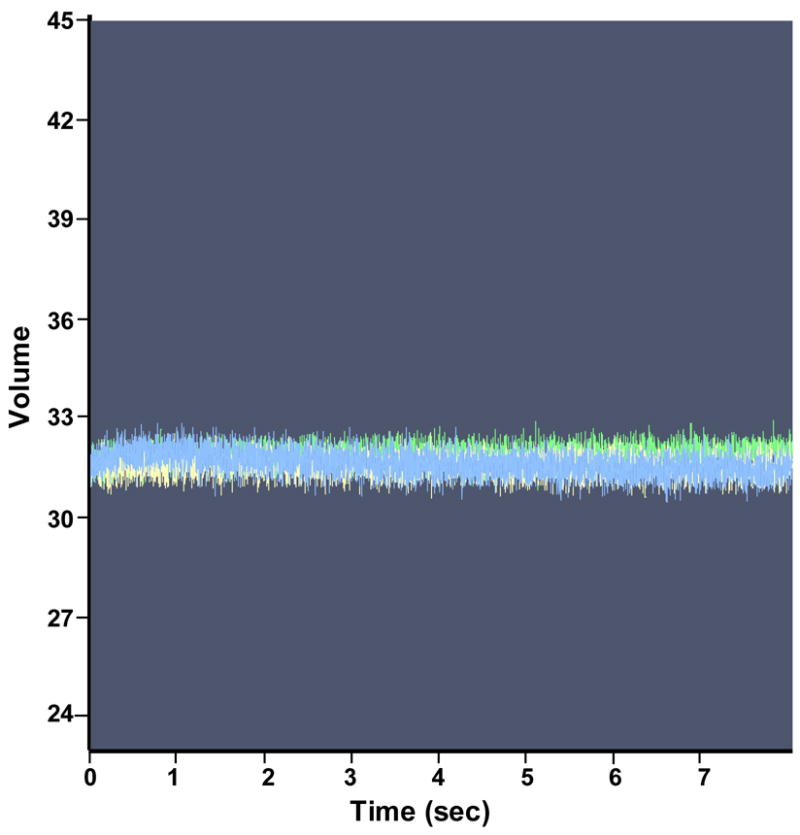

Figure 4.

Pre-steady state kinetics of wild type TRAP binding to GAGAU-1 RNA analyzed by stopped-flow fluorescence. (A) Changes in fluorescence after addition of TRAP: green line 0 nM TRAP; beige line 30 nM TRAP; red line 50 nM TRAP; blue line 60 nM TRAP; yellow line 90 nM TRAP. (B) Stopped-flow fluorescence analysis of TRAP binding to poly(A)(U)(GAGAA)10GAG RNA line colors are the same as indicated above. (C) Plot of the dependence of observed rate constants (kobs) on the concentration of WT TRAP binding to (GAGAA)11 RNA labeled with Fluorescein-10-U in 10 different positions after individual GAG-repeats. The number in the designation of the RNA indicates the location of the GAG repeat that contains a labeled U residue in the spacer for example GAGAU-1 contains the U residue in the spacer region following the first GAG repeat. GAGAU-1 (■); GAGAU-2 (▼); GAGAU-3 (+); GAGAU-4 (●); GAGAU-5 (▼); GAGAU-6 (○); GAGAU-7 (*); GAGAU-8 (×); GAGAU-9(◇); GAGAU-10 (▲) (D) Plot of the dependence of the observed rate constants (kobs) for on concentration of TRAP in the experiment of (R58A)10WT1 binding to (GAGAA)11 RNA labeled with Fluoroscein-10-U after first or tenth GAG-repeats GAGAU-1 (■); GAGAU-10 (▲).

Table 2.

Analysis of WT and (R58A)10WT1 TRAP binding to (GAGAA)11 RNA by stopped-flow fluorescence

| RNA | WT TRAP ka × 106 M−1 sec−1 | (R58A)10WT1 ka × 106 M−1 sec−1 |

|---|---|---|

| GAGAU-1a | 100.4 ± 3.7b | 1.69 ± 0.04 |

| GAGAU-2 | 109.2 ± 3.7 | - |

| GAGAU-3 | 119.3 ± 3.5 | - |

| GAGAU-4 | 60.8 ± 1.0 | - |

| GAGAU-5 | 56.7 ± 3.1 | - |

| GAGAU-6 | 45.9 ± 1.7 | - |

| GAGAU-7 | 50.7 ± 2.8 | - |

| GAGAU-8 | 51.8 ± 0.9 | - |

| GAGAU-9 | 44.1 ± 1.8 | - |

| GAGAU-10 | 38.1 ± 4.1 | 1.3 ± 0.05 |

| PolyA-GAGAU-1 | 20.4 ± 2.0 |

RNA consisted of 10 GAGAA repeats and one GAGAU repeat in which the U residue is replaced with Fluorescein-12-U. The location of the GAGAU repeat is indicated by the number; for example in GAGAU-1 the single U is contained in the spacer region after the first GAG repeat.

Association rate constants are the average of at least 3 individual experiments using at least 5 different concentrations of TRAP.

The ka values determined for WT TRAP binding to RNAs containing 10 GAGAA repeats and 1GAGAU were greatest when the fluor was after repeats 1, 2 or 3 (Figure 4C and Table 2). When the fluor was after repeats 4–10 the ka values were approximately 2–3 fold lower, with the lowest ka when the fluor was after repeat 10. There was a 3.2 fold difference between the greatest ka value when the fluor was near the 5′ end as compared to when it was between repeats 10 and 11 (Table 2). These results are consistent with our previous MBN protection studies16 and suggest that WT TRAP binds to its RNA target in a 5′ to 3′ directional fashion.

The (R58A)10WT1 hetero-11-mer bound to the RNA approximately 30–60 fold slower than WT TRAP (Figure 4D and Table 2). The ka values determined by stopped-flow fluorescence were again 5–6 fold greater than those obtained for this protein binding to (GAGUU)11 RNA by MBN protection (Table 1). Consistent with the MBN protection studies described in the previous section, the difference in ka values determined when the fluor was near the 5′ end of the binding site as compared to when it was near the 3′ end of the binding site was much smaller for (R58A)10WT1 (1.4 fold) than was observed for WT TRAP (3.2 fold), suggesting that the 5′ to 3′ directional binding is far less pronounced for this hetero-11-mer than for WT TRAP.

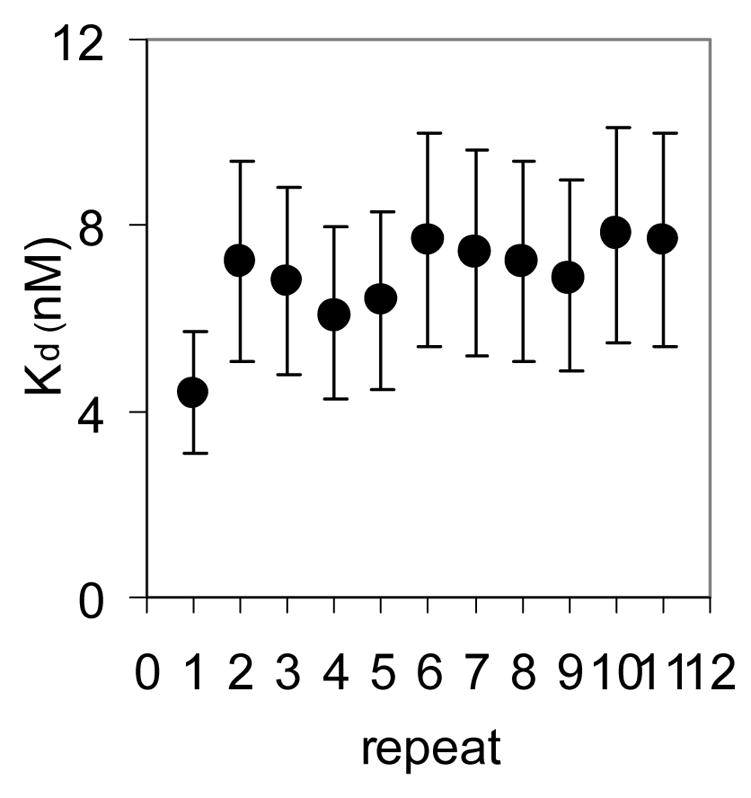

In vitro Transcription Attenuation

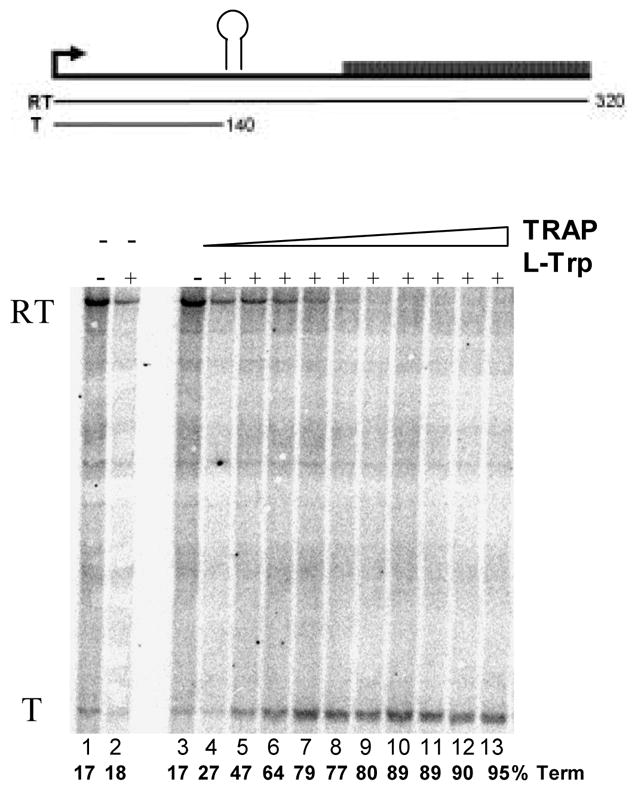

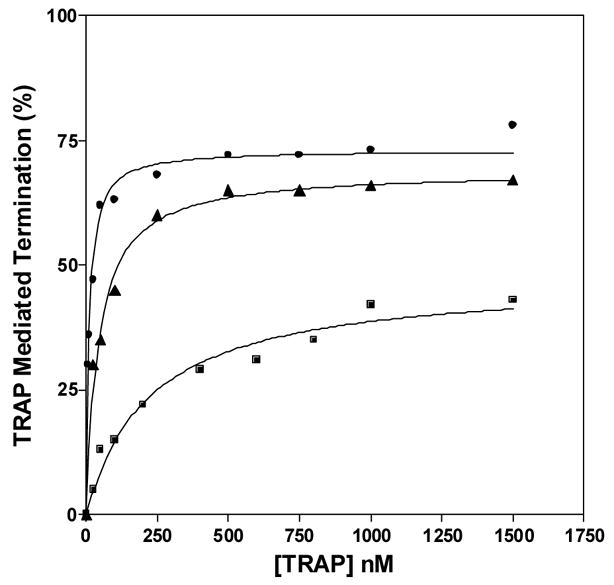

The role of TRAP in regulating transcription of the trp operon is to bind to the 5′ leader region of trp mRNA and induce formation of a transcription terminator structure upstream of trpE so as to halt transcription of the downstream structural genes (Figure 1A). To induce termination in the leader region, TRAP must bind and alter the structure of the leader RNA before the transcribing RNAP proceeds beyond the terminator region (approximately residue 140; see Figure 1A). The timing of TRAP binding to the nascent RNA, relative to the position of the polymerase transcribing the leader region is therefore critical in this regulatory mechanism. The footprinting and fluorescence data presented above show that the (T25A)10WT1 and (R58A)10WT1 hetero-11mers bind RNA with lower association rates than WT TRAP (Tables 1 and 2). Hence we examined the importance of the kinetics of TRAP binding to RNA in the attenuation mechanism by comparing the abilities of WT TRAP and these hetero-11mers to induce transcription termination in the trp leader region using an in vitro attenuation system13. We compared the abilities of these three TRAP proteins to induce termination in this system under conditions of various rates of elongation of RNAP by changing the concentration of nucleoside triphosphates (NTPs) in the transcription reaction17.

Single-round in vitro transcription of the trp leader region with B. subtilis RNAP produced two major products: a 318 nt read-through transcript (RT) and a 140 nt transcript terminated at the trp attenuator (T) (Figure 5A). In the absence of TRAP the read-through transcript was predominant and accounted for >80% of the total transcripts. As seen previously18, adding increasing amounts of tryptophan-activated WT TRAP increased the amount of terminated transcript and the levels of read-through transcript decreased concomitantly, indicating that TRAP induced termination in the trp leader region (Figures 5A and 5B). TRAP was more effective at inducing termination in the leader region when the transcription reactions were performed under conditions (5 μM and 50 μM NTPs) where RNAP elongates slower and TRAP was less efficient when RNAP elongates faster (400 μM NTPs) (Figure 5B). The efficiency of TRAP in this attenuation assay can be defined as the concentration of TRAP required to yield half maximal increase termination relative to that in the absence of TRAP. This value for WT TRAP when transcription was performed in the presence of 5, 50, and 400 μM NTP’s was 11, 109, and 224 nM, respectively.

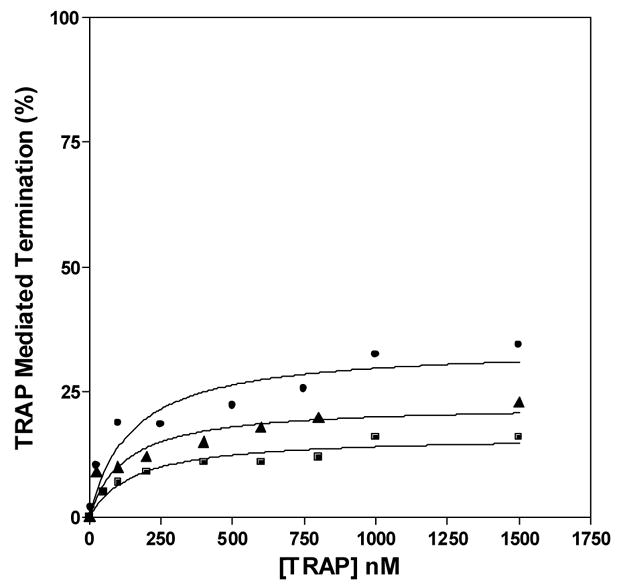

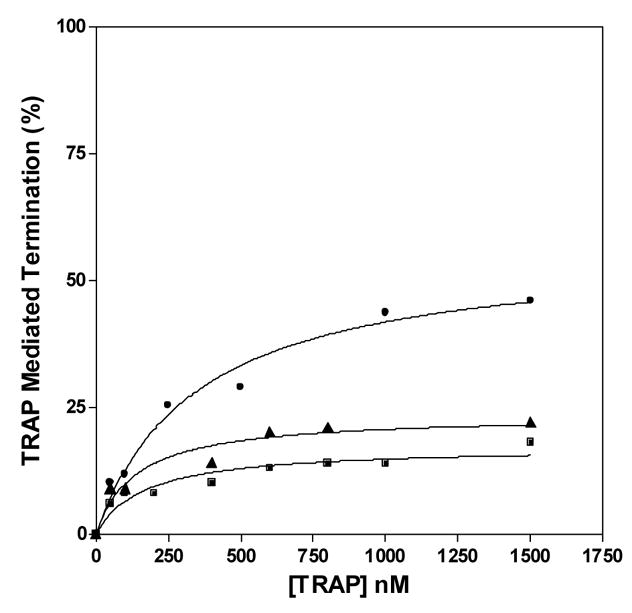

Figure 5.

In vitro transcription assay of TRAP-mediated transcription termination in the trp leader region. (A) 8% polyacrylamide-8M urea gel of the products of in vitro transcription of the trp leader region with B. subtilis RNAP in the absence and presence of WT TRAP with 5 μM nucleotide triphosphates. Positions of read-through (RT; 318 nt) and terminated (T; 140 nt) transcripts are indicated. Transcription reactions were carried out in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 1 mM L-Trp and/or TRAP. The triangle above the gel indicates increasing TRAP concentration from 50 to 1500 nM. The schematic diagram above the gel represents the transcription template with the trp promoter, regulatory region and start of the trpE gene. The stem-loop structure above indicates the position of the transcription terminator (attenuator) in the leader region. The lines below indicate the two potential transcripts. (B–D) Plots of the TRAP-mediated increase in termination at the trp attenuator calculated as the amount of terminated transcript divided by the sum of amounts of terminated and read-through transcripts. Transcription assays were performed at 5 μM (●), 50 μM (▲), and 400 μM (■) nucleotide triphosphates. (B) WT TRAP; (C) (T25A)10WT1; (D) (R58A)10WT1

The (R58A)10WT1 and (T25A)10WT1 TRAP hetero-11-mers were significantly less efficient at inducing termination in this system. At 50 and 400 μM NTP’s, both hetero-11-mers were virtually unable to induce transcription attenuation (Figures 5C and 5D) such that they caused only slight (< 15%) increases in termination even at the highest concentrations of protein. At the lowest concentration of NTPs (5 μM) tested, when RNAP elongates slowest, both hetero-11-mers induced more termination at the trp attenuator. (R58A)10WT1 TRAP, with the slowest on-rate for binding RNA (Table 1), showed only slightly more termination at the lowest NTP level than it induced at the higher NTP levels (Figure 5C), whereas (T25A)10WT1, with an intermediate on-rate, induced nearly 40% termination at the highest levels of protein when the NTP levels were 5 μM (Figure 5D). In all conditions, both hetero-11-mers were less efficient than WT TRAP at inducing termination in the trp leader and in both cases required over 400 nM protein to induce half-maximal increase in termination. In all cases there was little or no effect of adding TRAP to the transcription reactions in the absence of tryptophan (Figure 5A lane 3 and data not shown).

TRAP Hetero 11-mers in vivo

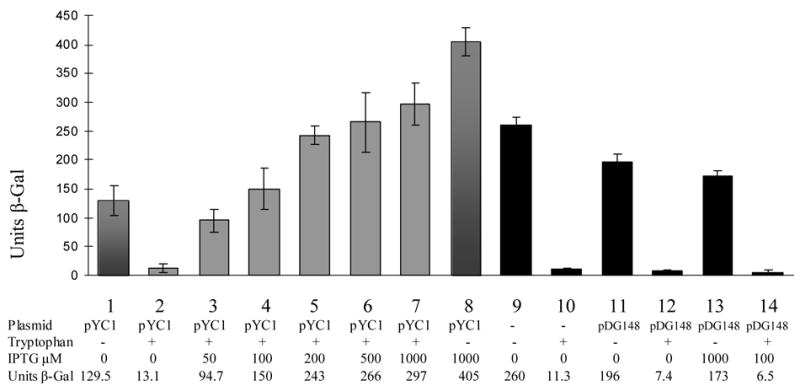

To create TRAP hetero-11-mers in vivo, we expressed K56A mutant TRAP subunits from the IPTG inducible spac promoter on plasmid pDG148 in B. subtilis CYBS12. This strain contains a wild-type mtrB gene for TRAP as well as a trpE’-’lacZ fusion under control of the trp promoter and regulatory leader region integrated at the amyE locus, which allowed us to examine the effects of hetero-11-mer formation on regulation of the trp operon. Similar to previous observations 5, β-galactosidase expression in CYBS12 was regulated approximately 23-fold in response to L-tryptophan in the growth medium (Figure 6; compare lanes 9 and 10). Transforming this strain with the plasmid vector pDG148 19 had little effect on β-galactosidase expression in the absence or presence of tryptophan or in response to IPTG (Figure 6; lanes 11–14). We then transformed CYBS12 with pYC1, which expresses K56A TRAP from the spac promoter. When the resulting strain was grown in the absence of IPTG, β-galactosidase expression was slightly reduced as compared to CYBS12 but remained negatively regulated approximately 10-fold in response to L-tryptophan (Figure 6 lanes 1 and 2). As the concentration of IPTG in the growth medium was increased from 0 to 1000 μM, expression of β-galactosidase in the presence of tryptophan increased from 13 units to 297 units (lanes 3–7). The presence of 1000 μM IPTG in the absence of added tryptophan resulted in very high levels of expression of β-galactosidase (lane 8). Previous studies have shown that K56A TRAP does not bind RNA and fails to regulate the trpE’-’lacZ fusion in vivo 7, the simplest interpretation of the results presented in Figure 6 is that when K56A subunits are expressed in the same cell as WT TRAP, the mutant subunits function in a dominant negative manner by forming hetero-11-mers with the WT subunits. Higher concentrations of IPTG increase the expression of K56A TRAP subunits such that the hetero-11-mers contain greater percentages of mutant subunits, and these hetero-11-mers are less capable of regulating the trpE’-’lacZ fusion.

Figure 6.

TRAP subunit mixing in vivo. Bar graph showing the effects of expressing K56A TRAP subunits on regulation of a trpE-lacZ fusion in CYBS12 B. subtilis, which expresses wild-type TRAP subunits from the chromosomal mtrB gene. Units of β-galactosidase are plotted for each strain under the growth conditions indicated below the graph. Black bars are for CYBS12 in the absence or presence of the empty E. coli/B. subtilis shuttle plasmid pDG148. Grey bars are for CYBS12 transformed with pYC1, which expresses K56A TRAP from the IPTG-inducible spac promoter. Levels of IPTG added to the growth medium are shown below the bars.

DISCUSSION

The Kinetics of TRAP Binding to RNA are Key to Transcriptional Regulation of the trp Operon

Bacteria use a variety of attenuation and antitermination mechanisms to regulate transcription of genes2. In most cases, environmental changes are sensed and the structure of the RNA upstream of the structural genes to be regulated is altered so as to favor or hinder formation of a transcription terminator3. A variety of biomolecules are used to influence the RNA structure in these mechanisms including ribosomes, RNA binding proteins, tRNAs, and small metabolites. In all cases, the regulatory molecule must alter the folding pattern of the nascent RNA transcript in a timely manner so as to influence the activity of RNAP before it has moved beyond the terminator region of the RNA; otherwise altering the structure of the RNA will not affect transcription.

In B. subtilis, the TRAP protein regulates attenuation of the trp operon by binding to the 5′ leader region of trp mRNA. Here we have examined the importance of the kinetics of TRAP binding for this regulatory mechanism. To do so, we compared the properties of WT TRAP to two TRAP hetero-11-mers, each composed of 10 mutant subunits and 1 WT subunit. The mutant subunits contained Ala substitutions in either Arg58 or Thr25, both of which are key residues that directly interact with the bound RNA or with the bound tryptophan respectively9,14,15. While homo-11-mers of either mutant protein showed no detectable binding to RNA14,15, the presence of just one WT subunit in either (R58A)10WT1 or (T25A)10WT1 allowed the hetero-11-mers to bind RNA with only 4- to 7-fold lower affinity than WT TRAP (Table 1). Based on studies of such TRAP hetero-11-mers, as well as of WT TRAP binding to RNAs with various numbers of NAG (N=G, A, U or C) repeats, we have proposed a two-step model for TRAP binding to its RNA targets14,15,20. In this model, TRAP first associates with a small subset (one to three) of the triplet repeats in the RNA to form an initiation complex, which is followed by wrapping the remaining repeats around the protein ring. Several studies suggest that formation of the initiation complex requires at least one WT subunit in the TRAP 11mer14,15. However, mutant subunits such as R58A or T25A, appear to function in the second binding step. The results presented here are consistent with this model. Both (R58A)10WT1 and (T25A)10WT1 hetero-11-mers protected all 11 repeats of (GAGAU)11 RNA equally and showed similar affinity for all 11 repeats (Figure 2C and 2D). The simplest interpretation of these observations is that these hetero-11-mers first associate with the RNA via their single WT subunit. This interaction tethers the RNA to the TRAP 11mer, which reduces the degrees of freedom in the reaction and allows the remaining 10 R58A or T25A subunits to interact with the RNA.

The most significant difference between the interaction of either of the hetero-11-mers and WT TRAP with RNA was decreased association rates for the hetero-11-mers such that their ka values were 12–60 fold lower than WT TRAP (Tables 1 and 2). This difference could be due to the requirement that binding to the RNA must initiate with the single WT subunit in the hetero-11-mers in a stochastic process as opposed to initiating with any subunit in WT TRAP. Both hetero-11-mers were also significantly less effective than WT TRAP at inducing transcription termination in the trp leader region in vitro (Figure 5). Moreover, there is a correlation between the association rates of the three proteins and their effectiveness at causing termination. WT TRAP had the fastest on-rate and was most efficient at causing termination in the attenuation assay (Table 1 and Figure 5). (R58A)10WT1 had the slowest on-rate and was least effective in inducing termination, whereas (T25A)10WT1 was intermediate between WT TRAP and (R58A)10WT1 in both properties. These observations support the hypothesis that the rate of TRAP binding to RNA is important in the attenuation mechanism.

Both WT TRAP and the hetero-11-mers were more effective at causing termination in the in vitro attenuation assay under conditions (lower NTP concentrations) that slow the rate of RNAP elongation (Figure 5). This observation is consistent with the model in which TRAP must bind and alter the structure of the nascent trp leader RNA before the transcribing RNAP has progressed beyond the transcription terminator (Figure 1). Thus slowing the rate of transcription elongation provides more time for TRAP to bind and induce formation of the terminator. Yakhnin and Babitzke have also shown that RNAP pauses in the trp leader region in vitro13. This pausing may also provide time for TRAP to bind and cause termination in the attenuation mechanism.

Previous MBN footprinting studies of WT TRAP binding to several sites consisting of 11 GAG repeats, including (GAGAU)11 RNA, showed that in all cases the association rates were greatest for repeats at the 5′ end of the binding site and least for those at the 3′ end16 (See also Figure 2E). From these observations we concluded that TRAP binds to its 11 repeat target sites in a 5′ to 3′ directional manner. A model for the mechanism by which TRAP binds first to the repeats at the 5′ end of the binding site suggests that the protein first associates with the 5′ end of the RNA and then translocates toward the binding site. Upon encountering several (G/U)AG repeats, TRAP binds more stably and forms an initiation complex, which is followed by wrapping the remaining repeats around the protein ring. Experiments in which the length between the 5′ end of the RNA and the 11 repeat binding site was varied are consistent with this hypothesis16 (B. Stilb, K. Pierce and P. Gollnick unpublished observations). Neither of the hetero-11-mers studied here showed significant variation in the rate of binding to any of the repeats within an 11GAG repeat binding site by MBN protection (Figure 3B and 3C) and (R58A)10WT1 showed only a slightly greater ka for binding to repeats at the 5′ end as compared to the 3′ end of the binding site by fluorescence studies (Figure 4D). Our binding model may explain why these hetero-11-mers fail to demonstrate 5′ to 3′ directional binding to the binding site. Several studies suggest that the hetero-11-mers must initiate binding to the RNA via a WT subunit14–16. If the single WT subunit in the hetero-11-mers used in this study is in random juxtaposition with relationship to the RNA when the protein encounters the 11 repeat binding site, then although the protein is moving 5′ to 3′ along the RNA, the repeat within the binding site that the single WT subunit associates with would be random. This effect would obscure the 5′ to 3′ binding to the 11 repeats.

Forming TRAP hetero-11-mers in vivo

Previous studies showed that K56A TRAP is defective in binding RNA in vtiro and does not regulate expression of a trpE’-’lacZ fusion in vivo 7. If expressing both K56A and WT TRAP proteins in vivo resulted in production of only the two separate homo-11-mers, then the K56A mutant protein would not interfere with the function of WT TRAP. In contrast, we observed that co-expressing K56A and WT TRAP in B. subtilis results in diminished regulation of a trpE’-’lacZ fusion (Figure 6). This observation implies that mixed heteromers form in vivo. In the presence of ≥ 200 μM IPTG and tryptophan, we observed greater expression of β-galactosidase (150–297 U) than in the absence of inducer and with no added tryptophan (129 U). Since this B. subtilis strain is trp +, the WT protein regulates the trpE’-‘lacZ fusion in response to endogenous tryptophan. However, expressing high levels of K56A TRAP eliminates most of the regulation in response to tryptophan and results in very high levels of expression from the fusion. Nevertheless, comparing columns 7 and 8 in Figure 6 shows that even with 1 mM IPTG, the trpE’-‘‘lacZ fusion is still regulated slightly in response to tryptophan (405 U vs 259 U). It is tempting to speculate that this result indicates that, as seen in vitro, hetero-11-mers with low fractions of WT subunits can still bind trp leader RNA, and regulate the trpE’-‘lacZ fusion but with reduced efficiency. However quantitative interpretation of these results is difficult without knowing the ratio of WT and mutant subunits produced in vivo. Nevertheless the results presented here provide evidence that K56A/WT hetero-11-mers are produced in vivo and that they have similar properties as those seen in vitro.

Transcriptional Control of trp Gene Expression in Response to Changes in Tryptophan Levels

The function of TRAP is to sense the level of free tryptophan in the cell and regulate expression of the trp genes appropriately. To do so, TRAP is activated to bind its RNA targets by binding up to 11 molecules of tryptophan. Tryptophan binding to B. subtilis TRAP exhibits slightly positive cooperativity (Hill Coefficient ≈ 1.5;14 and tryptophan binding to B. stearothermophilus TRAP is noncooperative8. These observations suggest that in either case, at intermediate levels of intracellular tryptophan, TRAP would bind less than the full complement of 11 tryptophans/11mer. Several observations made with the (T25A)10WT1 hetero-11-mer suggest that the number of bound tryptophans can influence TRAP’s ability to regulate transcription of the trp operon by affecting the mechanism by which TRAP binds to its 11-repeat binding site in the leader region of the trp mRNA. The presence of just one bound tryptophan significantly activates (T25A)10WT1 to bind RNA such that it shows only 4-fold lower affinity than tryptophan-activated WT TRAP with 11 tryptophans bound (Table 1). Nevertheless (T25A)10WT1 is much less effective than WT TRAP at inducing transcription termination in the in vitro attenuation assay, even at very high concentrations of (T25A)10WT1 (Figure 5). There are several possible explanations for the reduced activity of this hetero-11-mer. First (T25A)10WT1 binds to RNA slower than WT TRAP (>12-fold lower association rate constant; Table 1). Secondly (T25A)10WT1 does not show the 5′ to 3′ directional binding to the 11 repeat RNA target seen for WT TRAP (Figure 2). Hence both the rate of TRAP binding to RNA and its 5′ to 3′ binding mechanism may be important for TRAP’s role in controlling transcription attenuation.

In B. subtilis when the level of intracellular tryptophan changes, the number of tryptophan molecules bound to each TRAP 11mer will vary between 0 and 11. These changes affect the ability of TRAP to regulate transcription of the trp operon by altering the rate of TRAP binding and the mechanism by which it binds to the leader transcript. This situation may provide for more flexibility to fine tune TRAP-mediated regulation of transcription of the trp operon.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

All plasmids were propagated in Escherichia coli JM107. Plasmids pTZ18GAGAU and pTZ18GAGAU11polyA were described previously16,21. Plasmid pUC119trpl, which contains a 730bp EcoRI-HindIII fragment containing the B. subtilis trp promoter and leader sequence (−411 to +318 relative to the start of transcription)22 in pUC119 was used to create templates for in vitro transcription attenuation assays.

A series of plasmids were generated to use as templates for in vitro transcription to create fluorescently labeled RNAs for stopped flow analysis. These plasmids were based on an original plasmid containing 10 tandem repeats of GAGAA followed by GAG which was cloned between the EcoRI and HindIII sites of pTZ18U (US Biochemical) to create pTZGAGAA-1111. In each of the subsequent variations of this plasmid, one of the A residues in the AA spacers between GAG repeats was substituted with a T residue using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) using appropriate sets of complementary oligonucleotides. These plasmids were named according to the location of the T residue in the spacers, for example pTZGAGAT-1 contains the T residue in the spacer between the first and second GAG repeats.

The RNA trinucleotide ApGpC, corresponding to the first three residues of the trp operon transcript, was obtained from Dharmacon Research, Lafayette, CO. Mung Bean nuclease was purchased from USB Corporation, Cleveland, OH.

RNA Synthesis and TRAP Purification

A 55 nt RNA containing 11 tandem repeats of GAGAU was used for nitrocellulose filter binding assays (See below). This RNA was prepared by in vitro transcription of HindIII linearized plasmid pTZ18GAGAU with T7 RNA polymerase as described previously 23 using [α-32P]UTP (3000 Ci/mmol; Perkin Elmer). The 196 nt RNA 5′-GGGAAUU(C)11(A)47GGAAAGGGGGAAAAA(GAGAU)11AAAAAGGGGGAAAGG (A)46-3′ contains 11 repeats of GAGAU flanked on both the 5′ and 3′ sides by 60–80 residues of mostly polyA, and will be called (GAGAU)11polyA throughout this report. This RNA was transcribed in vitro with T7 RNA polymerase using plasmid pTZ18GAGAU11polyA as template16.

To fluorescently label RNA, plasmids pTZGAGAT1 etc. were linearized and used as templates for in vitro transcription with T7 RNA polymerase in the presence of 10mM Fluorescein-12-UTP (Enzo) using the RNAMaxx High Yield Transcription Kit (Stratagene). After labeling, the RNA was purified using RNeasy Mini Kit spin-columns (Qiagen).

WT and mutant TRAP proteins were expressed in E. coli strain BL21(DE3) (Novagen, Madison, WI) and purified by immunoaffinity chromatography24. His-tagged wild-type TRAP contains 6 tandem histidine residues on the C-terminus of the protein. This protein was expressed from plasmid pTZHisTRAP, which was generously provided by Paul Babitzke at Penn. State Univ., in E. coli BL21(DE3), and purified on nickel agarose according to the manufacturers instructions (Qiagen). The RNA- and tryptophan-binding properties of His-TRAP are indistinguishable from WT TRAP (A. Manfredo unpublished observations). The T25A and R58A mutant TRAP proteins used in this study were described previously7.

Creating Hetero-11-mers of TRAP (T25A)10WT1 and (R58A)10WT1

To create TRAP hetero-11-mers composed of 1 WT subunit and 10 mutant subunits (Figure 1B), we mixed a limiting amount of His-tagged wild-type TRAP with >100-fold excess of either mutant TRAP, denatured the proteins into unfolded monomers in the presence of ≥ 4 M guanidine hydrochloride for 1 hour at room temperature, then renatured 11mers by dialyzing against 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 8.015. We have shown previously that using this protocol, wild-type TRAP subunits assemble into fully functional 11mers15. Furthermore when mixing wild-type and mutant subunits, the composition of the resulting renatured hetero-11-mers is determined by the input ratios of the two types of subunits15. In the cases presented here, most of the renatured 11mers contain 11 mutant subunits (since they are in >100 fold excess in the mixture) but a few 11mers contain one His-tagged WT subunit; very few of the 11mers contain more than one WT subunit. Renatured hetero-11-mers that contain a His-tagged subunit were separated from mutant homo-11-mers by nickel-agarose chromatography as described by the manufacturer (Qiagen).

Nitrocellulose Filter Binding Assay

Equilibrium RNA binding affinity of TRAP in the presence of 1 mM L-tryptophan was measured using a filter binding assay described previously23. Data analysis was performed and Kd values were calculated using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software) as described previously20.

Mung Bean Nuclease Protection Assay

Equilibrium and pre-steady state Mung Bean nuclease (MBN) protection assays were performed as described previously16. For equilibrium experiments 0 to 90 nM TRAP was incubated with ≤ 5 pM 5′ 32P-labeled (GAGAU)11polyA RNA at room temperature (20 °C) until equilibrium was reached (≥ 30 min). For pre-steady state experiments 20 to 50 nM TRAP was incubated with ≤ 10 pM 5′ 32P-labeled RNA for 0–1200 sec at room temperature. Binding reactions (100 μl) contained 16 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 250 mM potassium glutamate and 1 mM L-tryptophan. For all footprinting experiments, digestion was initiated by adding 0.1 units of MBN and zinc chloride to 1 mM final concentration. Reaction mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 3 min. Mock treated control RNA samples were incubated in the absence of MBN. Nuclease digestion was stopped by adding 750 μl of freshly made 0.3 ammonium acetate, pH 7.0, 2 mM EDTA and 10 μg/ml yeast tRNA in ethanol. The samples were collected by centrifugation, washed with 70% ethanol, dried, and resuspended in loading buffer composed of 50% formamide, 10 mM EDTA, 0.025% bromophenol blue, 0.025% xylene cyanole. Samples were run on 8% polyacrylamide-8 M urea gels, fixed, dried and exposed to Molecular Dynamics phosphor storage screens. MW size markers were generated by a partial RNase T1 digest of the DNA/RNA chimera “ElevenRiboG”16

Data Analysis

Analysis of footprinting experiments was performed as described previously16. Digital images of the gels were obtained using a Molecular Dynamics Phosphorimager. Quantification of band intensities and analysis of protection were performed using Image Quant software using procedures developed by Brenowitz and coworkers25,26. More detailed information on defining areas protected by bound protein and explanation of pre-steady state conditions can be found in several excellent reviews25,26.

Values for “fractional protection” (P) of the binding sites were obtained by densitometric analysis of the digital images according to a described procedure using the equation16,25,26:

| Equation (1) |

Where I is the relative intensity, ‘n’ refers to any lane containing TRAP, ‘r’ refers to a reference lane without protein, ‘site’ denotes TRAP binding site(s), ‘std’ denotes a standard region of the gel used to correct for variations in loading each lane, which in this case was residues 135–170.

To obtain binding constants (Kd) the data were fit to equation (2) using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software):

| Equation (2) |

Where Pmax is the maximal fractional protection and [TRAP] is the concentration of TRAP.

Values for observed rate constants (kobs) were obtained by fitting the data to equation (3):

| Equation (3) |

Where Pmax is the maximal fractional protection, t is time.

Values for association rate constants (ka) were calculated from the equation:

| Equation (4) |

In each case we determined kobs and its standard error at several different concentrations of TRAP, derived ka values and averaged them.

Stopped-flow Fluorescence Measurements of TRAP binding to RNA were performed using Bio-Logic SFM-400 system with an MPS-60 microprocessor unit and Bio-Logic MOS450 optical system equipped with a 150-watt mercury-xenon lamp. The experiments were conducted with a 0.8 × 0.8 × 1 mm micro cuvette (FC-08) with a dead time of 1.1 ms. Several different concentrations of TRAP (as indicated in Figure 4) were mixed with 1μM labeled RNA at room temperature in 4mM Tris-HCl, 12mM HEPES, 4mM MgCl2 pH 8.0. Fluorescein was excited at 492 nm, and its emission was monitored at 525 nm with slit 20nm. The total flow rate was 14mL/s. The observed rate constants (kobs) for several different concentrations of TRAP were derived using BIO-KINE 32 (version 4.27) from the average of at least three independent experiments each with at least five replicates and the equation:

| Equation (5) |

where a is the slope, b is the offset and ci is the amplitude kobs is observed rate constant. Association rate constants (ka) were obtained from the slope of a plot of kobs versus the concentration of TRAP using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software).

In vitro Transcription Attenuation Assay

Single-round in vitro transcription attenuation assays were performed by modification of previously described methods13. The template containing the B. subtilis trp promoter, 5′ leader region, and the start of trpE (−411 to +318 relative to the start of transcription) was prepared by PCR amplification of this region from plasmid pUC119trpL using the standard Reverse and −40 Forward oligonucleotide sequencing primers. The resulting 775 bp PCR product was subsequently digested with HindIII and purified by phenol extraction, ethanol precipitated, washed twice with 70% ethanol, collected, dried, and resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 0.1 mM EDTA.

Two-step single-round in vitro transcription reactions were performed in 40 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 4 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 5 mM DTT. In the first step, a stable halted transcription complex was formed by initiating transcription from the trp promoter for 10 min at 37 °C in a reaction containing 60 nM DNA template, 100 μM (or 15 μM) ApGpC, 20 μM (or 5 μM) ATP and GTP, 100 μM (or 5 μM) [α-32P]UTP (3000 Ci/mmol; Perkin Elmer) and 50 μg/ml B. subtilis RNA polymerase. In the absence of CTP, transcription halts after nucleotide 12 in the trp leader region. Prior to elongation, various concentrations (0 to 2000 nM) of TRAP and 1 mM L-tryptophan were added to the halted complex. Elongation was resumed by addition of all four nucleoside triphosphates (NTPs) at 400 μM, 50μM or 5 μM, together with heparin to final concentration of 100 μg/ml. The elongation reactions were incubated at 37 °C for 20 min and then stopped by adding an equal volume of gel loading buffer (95% formamide, 20 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, 0.05 % each bromophenol blue and xylene cyanol). The amount of TRAP-independent termination was also determined in each case. Samples were run on 8% polyacrylamide-8 M urea gels, fixed, dried and exposed to Molecular Dynamics Storage Phosphor Screens. The efficiency of termination was calculated as the amount of terminated transcript divided by the sum of terminated and readthrough transcripts.

β-galactosidase assays

Plasmid pYC1 was created by ligating a mutant mtrB gene, encoding K56A TRAP, on a Hind III to Sal I fragment into similarly digested pDG148 19. In this plasmid, K56A TRAP is expressed from the IPTG inducible spac promoter 27. CYBS12 B. subtilis5 transformed with pYLC1 was grown in minimal salts 28 with 0.2% glucose, 0.2% acid-hydrolyzed casein, 2 μg/ml kanamycin and 5 μg/ml phleomycin in the absence or presence of 50 μg/ml L-tryptophan and various concentrations of IPTG at 37°C until the optical density of the culture at 600 nm reached between 0.4 and 0.8. β-galactosidase activity was assayed as described previously 5. Values reported are the average from 3 different colonies, each analyzed in duplicate. Standard deviations were less than 20% of the mean.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Paul Babitzke for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by grant GM62750 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Babitzke P, Gollnick P. Posttranscriptional Initiation Control of Tryptophan Metabolism in Bacillus subtilis by the trp RNA-Binding Attenuation Protein (TRAP), anti-TRAP, and RNA Structure. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:5795–5802. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.20.5795-5802.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gollnick P, Babitzke P, Antson A, Yanofsky C. Complexity in Regulation of Tryptophan Biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis. Annu Rev Genet. 2004 doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.093745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gollnick P, Babitzke P. Transcription attenuation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1577:240–250. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(02)00455-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merino E, Babitzke P, Yanofsky C. trp RNA-binding attenuation protein (TRAP)-trp leader RNA interactions mediate translational as well as transcriptional regulation of the Bacillus subtilis trp operon. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6362–6370. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.22.6362-6370.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuroda MI, Henner D, Yanofsky C. cis-Acting sites in the transcript of the Bacillus subtilis trp operon regulate expression of the operon. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3080–3088. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.7.3080-3088.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antson AA, Otridge JB, Brzozowski AM, Dodson EJ, Dodson GG, Wilson KS, Smith TM, Yang M, Kurecki T, Gollnick P. The Three Dimensional Structure of trp RNA-binding Attenuation Protein. Nature. 1995;374:693–700. doi: 10.1038/374693a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang M, Chen X-P, Millitello K, Hoffman R, Fernandez B, Baumann C, Gollnick P. Alanine-scanning Mutagenesis of Bacillus subtilis trp RNA-binding Attenuation Protein (TRAP) Reveals Residues Involved in Tryptophan Binding and RNA Binding. J Mol Biol. 1997;270:696–710. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McElroy C, Manfredo A, Wendt A, Gollnick P, Foster M. TROSY-NMR studies of the 91 kDa TRAP protein reveal allosteric control of a gene regulatory protein by ligand-altered flexibility. J Mol Biol. 2002;323:463–473. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00940-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antson AA, Dodson EJ, Dodson GG, Greaves RB, Chen X-P, Gollnick P. Structure of the trp RNA-binding attenuation protein, TRAP, bound to RNA. Nature. 1999;401:235–242. doi: 10.1038/45730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Babitzke P, Yanofsky C. Structural features of L-tryptophan required for activation of TRAP, the trp RNA-binding attenuation protein of Bacillus subtilis. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12452–12456. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.21.12452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hopcroft NH, Manfredo A, Wendt AL, Brzozowski AM, Gollnick P, Antson AA. The interaction of RNA with TRAP: the role of triplet repeats and separating spacer nucleotides. J Mol Biol. 2004;338:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hopcroft NH, Wendt AL, Gollnick P, Antson AA. Specificity of TRAP-RNA interactions: crystal structures of two complexes with different RNA sequences. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2002;58:615–621. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902003189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yakhnin AV, Babitzke P. NusA-stimulated RNA polymerase pausing and termination participates in the Bacillus subtilis trp operon attenuation mechanism in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11067–11072. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162373299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li PTX, Gollnick P. Using Heter-11-mers Composed of Wild Type and Mutant Subunits to Study Tryptophan Binding to TRAP and its Role in Activating RNA Binding. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:35567–35573. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205910200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li PTX, Scott DJ, Gollnick P. Creating Hetero-11-mers Composed of Wild-type and Mutant Subunits to Study RNA Binding to TRAP. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:11838–11844. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110860200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barbolina MV, Li X, Gollnick P. Bacillus subtilis TRAP binds to its RNA target by a 5′ to 3′ directional mechanism. J Mol Biol. 2005;345:667–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.10.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grundy FJ, Henkin TM. Kinetic analysis of tRNA-directed transcription antitermination of the Bacillus subtilis glyQS gene in vitro. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:5392–9. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.16.5392-5399.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Babitzke P, Yanofsky C. Reconstitution of Bacillus subtilis trp attenuation in vitro with TRAP, the trp RNA-Binding attenuation protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:133–137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.1.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stragier P, Bonamy C, Karmazyn-Campelli C. Processing of a sporulation sigma factor in Bacillus subtilis: how morphological structure could control gene expression. Cell. 1988;52:697–704. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90407-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elliott M, Gottlieb P, Gollnick P. The mechanism of RNA binding to TRAP: initiation and cooperative interactions. RNA. 2001;7:85–93. doi: 10.1017/s135583820100173x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baumann C, Xirasagar S, Gollnick P. The trp RNA-binding Attenuation Protein (TRAP) from B. subtilis binds to unstacked trp leader RNA. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19863–19869. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.32.19863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shimotsu H, Henner DJ. Characterization of the Bacillus subtilis tryptophan promoter region. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:6315–6319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.20.6315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baumann C, Otridge J, Gollnick P. Kinetic and Thermodynamic Analysis of the Interaction Between TRAP (trp RNA-binding Attenuation Protein) and trp Leader RNA from Bacillus subtilis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12269–12274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.21.12269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Otridge J, Gollnick P. MtrB from Bacillus subtilis binds specifically to trp leader RNA in a tryptophan dependent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:128–132. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.1.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brenowitz M, Senear DF. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Wiley; New York: 1989. DNase I footprint analysis of protein-DNA binding; p. 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brenowitz M, Senear DF, Jamison E, Dalma-Weiszhausz D. Quantitative DNase I footprinting. In: Revzin A, editor. Footprinting Techniques for Studying Nucleic Acid-Protein Complexes. Vol. 1. New York: Academic Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yansura DG, Henner DJ. Use of the Escherichia coli lac repressor and operator to control gene expression in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:439–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.2.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spizizen J. Transformation of Biochemically Deficient Strains of Bacillus Subtilis by Deoxyribonucleate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1958;44:1072–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.44.10.1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]