Abstract

Mutations in the protein kinase C γ (PKCγ) gene cause spinocerebellar ataxia type 14 (SCA14), a heterogeneous neurodegenerative disorder. Synthetic peptides (C1B1) serve as gap junction inhibitors through activation of PKCγ control of gap junctions. We investigated the neuroprotective potential of these peptides against SCA14 mutation-induced cell death using neuronal HT22 cells. The C1B1 synthetic peptides completely restored PKCγ enzyme activity and subsequent control of gap junctions. PKCγ SCA14 mutant proteins were shown to cause aggregation which initially resulted in endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and cell apoptosis as demonstrated by phosphorylation of PERK on Thr981, activation of caspase-12, increases in BiP/GRP78 protein levels, and consequent activation of caspase-3. Pre-incubation with C1B1 peptides completely abolished these SCA14 effects on ER stress and caspase-3 activation, suggesting that C1B1 peptides protect cells from apoptosis through inhibition of gap junctions by restoration of PKCγ control of gap junctions, which may result in neuroprotection in SCA14.

Keywords: Spinocerebellar ataxia, protein kinase C γ, gap junctions, endoplasmic reticulum stress, protein aggregation, caspase-12, PERK, BiP/GRP78, caspase-3, C1B1 synthetic peptide, neuroprotection

Introduction

Spinocereballar ataxias (SCAs) are heterogeneous, autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disorders clinically characterized by various symptoms, such as progressive ataxia of gait and limbs, cerebellar dysarthria, and abnormal eye movement [1]. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 14 (SCA14) is caused by mutations in the PKCγ gene with onset age as early as three years [2,3]. The mechanistic aspects of this disease remain unknown. No treatment is available yet.

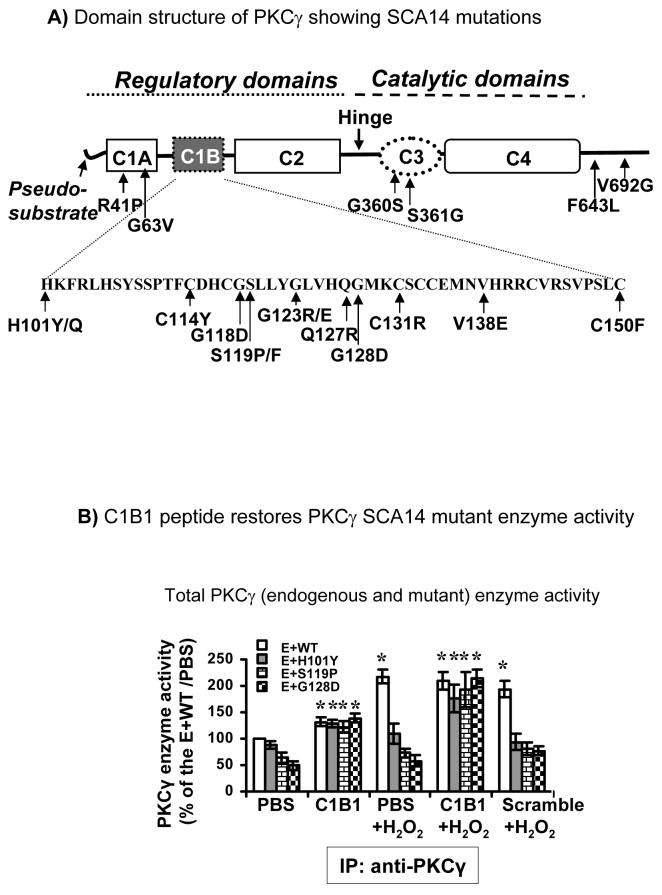

PKCγ, a classical PKC, is particularly abundant in cerebellar Purkinje cells and in hippocampal pyramidal cells [4]. PKCγ consists of C1 and C2 regulatory domains and C3 and C4 catalytic domains. The C1 domain contains two tandem repeat, Cys-rich regions, C1A and C1B. The SCA14 mutations occur throughout the PKCγ gene from the regulatory to catalytic domains and also include a six-pair in-frame deletion (ΔK100-H101) and a splice site mutation (D595D). Most mutations occur in the C1B region [2,3,5-13, see Figure 1A for location of mutations]. Inactivated PKCγ is associated with the docking protein 14-3-3. C1B1 synthetic peptides (residues 101-112 of PKCγ) activate PKCγ through competitively binding to 14-3-3 proteins [14]. The C1B1 peptides cause release of PKCγ from 14-3-3 and activation of PKCγ enzyme activity. This results in phosphorylation of connexin43 (Cx43) gap junction proteins. Thus, C1B1 peptides serve as gap junction inhibitors.

Figure 1. PKCγ spinocerebellar ataxia type 14 (SCA14) mutations A.

Domain structure of PKCγ showing SCA14 mutations. The amino acid sequence of the C1B subdomain is shown in the insert below. PKCγ SCA14 missense mutations are indicated. B. HT22 cells were transiently transfected with wild type HA:PKCγ (WT) or HA:PKCγ SCA14 mutants, H101Y, S119P, or G128D. After 24 hr incubation, cells were treated with C1B1 or scrambled peptides (100 μM, 2 hr) and with or without additional 100 μM H2O2 for 20 min. The whole cell extracts were used to immunoprecipitate both endogenous PKCγ (E) and HA tagged wild type PKCγ (E+WT) or mutants by anti-PKCγ antibodies. The precipitates were used for the enzyme sources to determine enzyme activity as described in the Methods Section. C1B1=C1B1 peptides; Scramble=Scrambled peptides. *: significant difference at p<0.05

Gap junctions provide a cell-to-cell communication role as electrical synapses in the central nervous system. The passage of cell death signals through open gap junctions is linked to neuronal cell death [15]. The process is well-documented in brain injury caused by cerebral ischemia [15-17]. It is apparent that proper control of gap junctions is essential for neuronal cell survival.

We have previously demonstrated that lens epithelial cells with PKCγ SCA14 mutants (H101Y, S119P, or G128D) lack PKCγ enzyme activity even when endogenous PKCγ is present [18]. This dominant negative effect on endogenous PKCγ has been linked to failure of control of gap junctions and this causes cells to be more susceptible to H2O2-induced, caspase-3-dependent cell apoptosis [18]. In the current study, we used the hippocampal HT22 cells which has endogenous PKCγ, thus, the overexpression of the SCA14 mutant PKCγ should more directly reflect SCA14 patients who are heterozygous. This is the first report of expression of SCA14 mutations in a neuronal cell line. We demonstrated that neuronal HT22 cells with overexpressed PKCγ SCA14 mutants were apoptotic. Pre-incubation with C1B1 synthetic peptides completely abolished the SCA14 effects on cell apoptosis through restoration of PKCγ control of gap junctions.

Materials and Methods

Cell cultures

The murine hippocampal HT22 cells were cultured in DMEM (high glucose, 4.5 g/L) (Invitrogen, California) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum and 50 μg/ml gentamicin, 0.05 unit/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin, pH 7.4 at 37°C in an atmosphere of 95 % air and 5 % CO2.

PKCγ SCA-14 mutant plasmid construction and transfection

C-terminal EGFP-tagged PKCγ SCA14 mutants (H101Y, S119P, or G128D) were generated previously [18]. In addition, PKCγ SCA14 mutant cDNA was cloned into the pCMVHA vector (Clontech, California) to generate N-terminal HA-tagged PKCγ SCA14 mutants by introducing 5'EcoRI and 3'KpnI sites. Construct sequences were verified by sequencing. Plasmid DNA transient transfection into ∼ 60 % confluent HT22 cells was performed by Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen, California) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Transfection efficiency of both constructs with either an EGFP or HA tag was greater than 90 % as determined by immunocytochemistry (for HA-tagged vectors) and/or confocal microscopy (for EGFP-tagged vectors).

C1B1 Synthetic Peptide

Synthetic peptide C1B1 corresponding to residues 101-112 (sequence: HKFRLHSYSSPT) of wild type PKCγ, was synthesized by Sigma Genosys (Woodlands, Texas). Nonspecific scrambled peptide was used as a negative control (sequence: SFGKCHLYPKV). Peptides were added at 100 μM for 2 hours at 37 °C as previously described [14].

Gap Junction Activity Assay

HT22 cell gap junction activity was measured by the scrape loading/dye transfer assay as described previously [19]. Briefly, after treatments, 2.5 μl of both 1% Lucifer Yellow and 0.75% Rhodamine Dextran (Molecular Probes, Oregon) were added at the center of the coverslip of transiently transfected cells in culture. Then two cuts crossing each other were made passing through the dye. After additional incubation (10 min), the cells were fixed in 2.5% paraformaldehyde, and dye transfer was evaluated by fluorescent microscopy. For quantitation, the extent of dye transfer was calculated by counting the number of Lucifer Yellow-labeled cells from the initial scrape with subtraction of Rhodamine Dextran label as a cell damage control. Four points per slide were photographed. The experiments were repeated six times, and data are mean ± S.E.M.

Western blot and immunoprecipitation

Western blotting and immunoprecipitation were performed as described previously [19]. Anti-HA antibody was purchased from Covance (Berkeley, California), anti-PKCγ and GFP were from BD Biosciences (San Jose, California), anti-BiP/Grp78 was from Stressgen (Ann Arbor, Michigan), anti-pPERK (Thr981) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotech (Santa Cruz, California), and anti-caspase-3, caspase-12 and α-tubulin were purchased from Cell Signaling (Danvers, Maryland).

Total PKC>γ (endogenous + exogenous wild type or SCA14 mutants) enzyme activity assay

Specific PKCγ activity was analyzed as described [18]. Equal protein amounts of whole cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with PKCγ antisera (1:100). Immunoprecipitated PKCγ/agarose bead complexes were used for the enzyme sources, and PKCγ enzyme activity was analyzed according to the manufacturer's instructions. The enzyme activity was normalized by calibration of the relative level of phosphorylated substrates (phospho-PepTag peptides, phosphorylated by PKCγ) to the relative amount of endogenous PKCγ and exogenous PKCγ or mutants in the immunoprecipitation as determined by Western blotting, and was expressed as % of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-treated specific PKCγ activity.

Evaluation of cells with aggregation

After transfection for 24 hr, the cells were treated with C1B1 peptides and/or H2O2 for particular time periods. Cells were fixed with 2.5% paraformaldehyde and labeled with primary antibodies against BiP/Grp78, GFP or HA and the secondary antibodies against Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-rabbit IgG or Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (Molecular Probes, Oregon). The cells were then examined by confocal microscopy. Ten points per slide were photographed, three slides for each treatment, totally at least 300 transfected cells were counted for each group. For quantitation, cells with aggregating proteins were classified into massive and/or dot-like aggregation [5]. Examples showing protein aggregation types are shown in Figure 3. The % of cells with each type aggregation vs total cells was counted (Table 1).

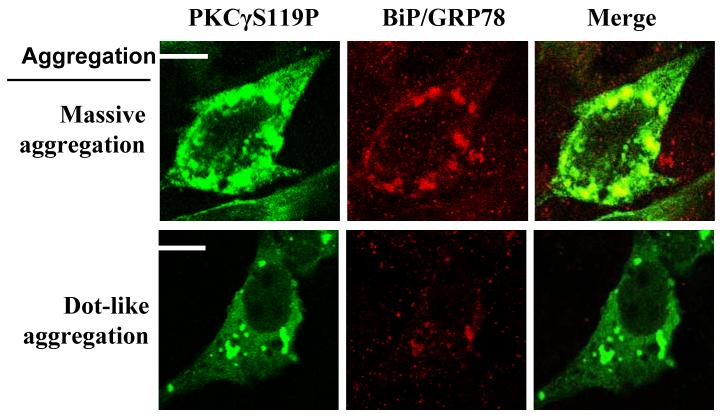

Figure 3. PKCγ SCA14 mutant protein aggregation: localization with BiP/GFP78 proteins.

Transiently transfected cells (24 hr post-transfection) were fixed in 2.5 % paraformaldahyde. HA tagged PKCγ or mutants and endogenous BiP/GRP78 were labeled by specific antisera as indicated. Protein aggregation was defined as described in the Methods Section. Representative protein aggregation forms, massive and dot-like aggregation, are shown with colocalization of BiP/GRP78.

Table 1. Protein aggregation of cells transfected with wild type (WT) or SCA 14 mutant HA:PKCγ in hippocampal HT22 cells.

Results are mean+/− S.E.M.. Protein aggregation rate= % of observed cells/total examined cells with WT or SCA14 mutant HA:PKCγ; C1B1=C1B1 peptides; Scramble=scrambled peptides

| Treatment | PBS | C1B1 | Scramble | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

HA:PKCγ Aggregation |

WT | H101Y | S119P | G128D | WT | H101Y | S119P | G128D | WT | H101Y | S119P | G128D |

| Massive | 1.6 ± 0.6 |

7.4 ± 0.9 |

8.5 ± 0.8 |

7.6 ± 0.5 |

1.6 ± 0.5 |

3.4 ± 0.8 |

4.1 ± 0.8 |

3.8 ± 0.3 |

1.7 ± 0.6 |

6.6 ± 1.1 |

6.9 ± 0.7 |

7.4 ± 0.6 |

| Dot-like | 2.6 ± 0.5 |

0.9 ± 0.7 |

0.7 ± 0.6 |

1.4 ± 0.6 |

2.6 ± 0.5 |

1.8 ± 0.9 |

2.4 ± 0.5 |

1.7 ± 0.3 |

2.2 ± 0.5 |

0.4 ± 0.1 |

0.6 ± 0.2 |

0.9 ± 0.7 |

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis employed in this paper is the unpaired Student's t-Test. All analyses represent at least triplicate experiments. The level of significance (*) was considered at p ≤ 0.05. All data are mean ± S.E.M.

Results

C1B1 synthetic peptides rescue activity of PKCγ

To determine if PKCγ enzyme activation was affected in neuronal cells and if PKCγ activity could be restored by C1B1 synthetic peptides, we overexpressed wild type PKCγ and/or PKCγ SCA14 mutants with either HA or EGFP tags in hippocampal HT22 cells. We found that SCA14 mutants with either HA or EGFP tags lack PKCγ enzyme activity (data not shown). We also measured total PKCγ enzyme activities using anti-PKCγ antibodies to immunoprecipitate both endogenous wild type PKCγ and exogenous wild type PKCγ or SCA14 mutants with HA tags. Results demonstrated that the expression of exogenous wild type PKCγ did not affect PKCγ enzyme activation by H2O2 (Fig. 1B, E+WT, PBS vs PBS+H2O2). However, expression of SCA14 mutants caused lowered basal level of endogenous and exogenous PKCγ enzyme activities and caused a failure to be activated by H2O2. Endogenous PKCγ protein levels were not changed as determined by Western blotting (not shown). The results indicate that the presence of the exogenous PKCγ SCA14 mutants, but not the wild type PKCγ, prevented normal function and activation of endogenous wild type PKCγ. This is in agreement with our previous observation in lens epithelial cells with EGFP-tagged PKCγ SCA14 mutants [18]. Application of C1B1 peptides increased total PKCγ enzyme activity in cells with exogenous wild type PKCγ (Fig. 1, E+WT, C1B1 vs PBS). Of greater significance, C1B1 peptides (100 μM, 2 hr), but not the scrambled peptides, completely abolished the dominant negative effects of SCA14 mutations (H101Y, S119P, or G128D). Total PKCγ activity of cells with SCA14 mutants were significantly increased by C1B1 peptides when compared to the wild type (Fig. 1B, C1B1 vs PBS), which were further enhanced by H2O2 (Fig. 1, C1B1 + H2O2 vs C1B1).

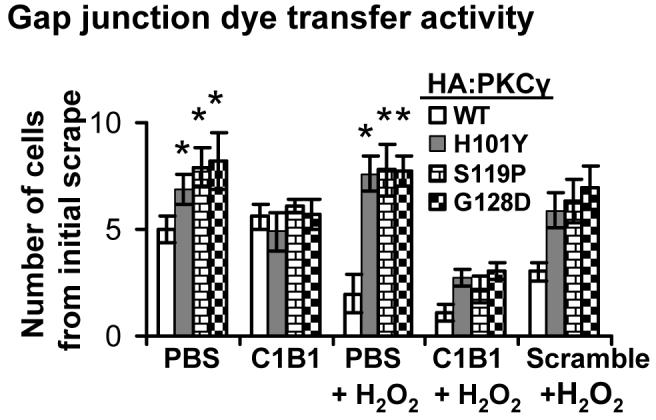

C1B1 synthetic peptides restore PKCγ control of gap junction activity

We wished to further determine whether C1B1 peptides alter control of gap junctions through restoration of PKCγ enzyme activity in HT22 cells transfected with SCA14 mutants. Scrape loading/dye transfer assays were performed to determine gap junction activity in HT22 cells which were transiently transfected with HA-tagged PKCγ SCA14 mutants with transfection efficiency of greater than 90 %. Gap junction activity results (Figure 2) demonstrated that overexpression of PKCγ SCA14 mutants caused increased basal dye transfer gap junction activity when compared to that of cells overexpressing wild type PKCγ (PBS columns). However, while H2O2 (100 μM, 20 min) significantly inhibited gap junction activity in HT22 cells with HA-tagged wild type PKCγ, the same level of H2O2 failed to inhibit dye transfer in cells with PKCγ SCA14 mutants overexpressed against a wild type PKCγ background (PBS+H2O2 columns). We further applied 100 μM C1B1 to the transfected cells for 2 hr, with or without addition of 100 μM H2O2 for an additional 20 min. Non-functional, scrambled peptides were used as negative controls. Dye transfer activity experiments demonstrated that pre-incubation with C1B1 only, but not scrambled peptides, and/or followed by H2O2 treatments resulted in inhibition of gap junction activity (Fig. 2, C1B1 vs C1B1+ H2O2), indicating that the C1B1 could overcome a failure of control of gap junctions caused by PKCγ SCA14 mutants in HT22 cells.

Figure 2. Overexpression of PKCγ ataxia mutations leads to a failure of H2O2 inhibition of gap junction activity.

After treatments with H2O2 (100 μM, 20 min), with or without the pre-incubation with C1B1 peptides (100 μM, 2 h), transiently transfected HT22 cells with HA-tagged wild type PKCγ or its SCA14 mutants were used for scrape loading/dye transfer assays to evaluate gap junction activity as described in the Methods Section. The experiments were repeated six times, and data are mean ± S.E. *: significant difference at p<0.05

PKCγSCA14 mutations induce protein aggregation in endoplasmic reticulum (ER)

We examined the cellular distribution of overexpressed wild type or SCA14 mutant PKCγ with either EGFP or HA tag by immunocytochemistry in hippocampal HT22 cells with or without C1B1 pre-incubation (2 hr). Massive and dot-like protein aggregation occurred independent of EGFP and/or HA tags, similar to the previous report [5], although the overall percentage of cells with protein aggregation was low (less than 10 %) (Table 1, and Figure 3 for sample images). HT22 cells with PKCγ SCA14 mutants had more massive aggregation than that found in the cells with wild type PKCγ. However, dot-like aggregation levels were low either in the cells with wild type or mutant PKCγ. C1B1 pre-incubation (100 μM, 2 hr) experiments demonstrated that C1B1 peptides, but not scrambled peptides, caused decreases in the number of the cells with massive aggregation (Table 1).

Further, in the neuronal HT22 cells, protein massive aggregation of wild type or SCA14 mutants of PKCγ, but not dot-like aggregation, was largely colocalized with BiP/GRP78, an ER marker (Fig. 3), indicating that ER stress might mediate PKCγ SCA14 mutation-induced cell apoptosis.

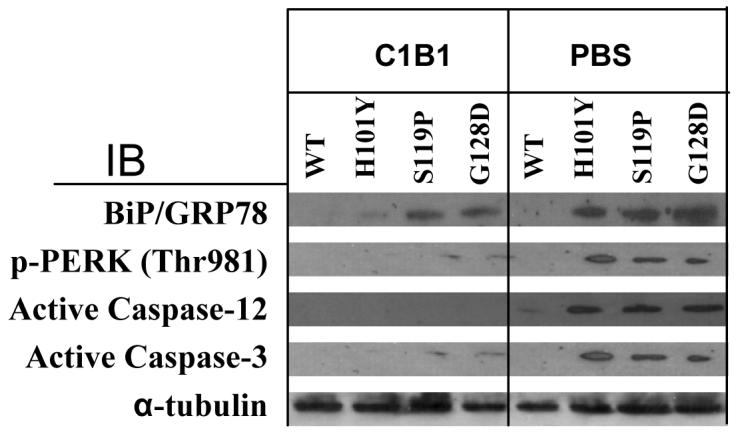

C1B1 synthetic peptides prevent ER stress and subsequent activation of caspase-12 and -3

Western blotting results in Figure 4 demonstrated that PKCγ SCA14 mutations caused elevation of BiP/GRP78 protein levels, phosphorylation of PERK on Thr981, activation of caspase-12, and consequent activation of caspase-3 (Fig. 4, PBS columns). Data indicate that massive aggregation of SCA14 mutant proteins initiated ER stress and cell apoptosis in HT22 cells.

Figure 4. C1B1 peptides decrease HT22 cell apoptosis and subsequent ER stress induced by PKCγ SCA14 mutations.

Cells, transiently transfected with wild type PKCγ or SCA14 mutation cDNA with HA tags for 22 hr, were then incubated with C1B1 peptides (100 μM, 2 hr) or PBS as a negative control. After that, whole cell lysates were used for Western blotting. α-tubulin is used as loading controls. WT, wild type PKCγ. IB, immunoblot

Finally, we determined the effects of C1B1 peptides on ER-stress and cell apoptosis by Western blotting in cells treated with 100 μM C1B1 peptides for 2 hr. Results in Figure 4 (C1B1 columns) clearly demonstrated that C1B1 peptides completely abolished the effects of PKCγ SCA14 Mutations on PERK phosphorylation on Thr981 and activation of caspase-12 and caspase-3 (WT vs mutants).

Discussion

In the current study, we found that the dominant negative effect of PKCγ SCA14 mutations on endogenous PKCγ could be abolished by C1B1 synthetic peptides in transiently transfected hippocampal HT22 cells. Restoration of control of gap junctions by C1B1 peptide activation of PKCγ prevented cells from apoptotic cell death. These apoptotic signals were initiated by ER stress in cells with massive aggregation of SCA14 mutant proteins. This is designated as a gap junction “Bystander” effect. C1B1 peptides block this pathway through rescuing PKCγ control of gap junctions.

The SCA14 is a newly identified autosomal neurodegenerative disorder. Regarding the molecular mechanism of SCA14, Verbeek et al. reported that PKCγ SCA14 mutants had increased kinase activity, altered membrane targeting, but no mutant protein aggregation when overexpressed in kidney COS-7 cells [8]. However, Seki et al. reported that SCA14 mutants were susceptible to aggregation which occurred largely in the Golgi complex in the Chinese hamster ovary CHO-K1 [5]. These contradictory conclusions indicate that irrelevant cell lines, such as kidney COS-7 and Chinese hamster ovary CHO-K1, may not be appropriate in vitro cell systems to study the molecular mechanism of a neurodegerative disorder, such as SCA14. In our lab, we used well-characterized, neuronal hippocampal HT22 cells as a model [20]. We have demonstrated that these mutant PKCγ's cause a caspase-3-linked apoptosis triggered by ER stress in HT22 cells which spreads through open gap junctions (Figure 3 and 4).

Protein misfolding in ER initiates the unfolded protein response (UPR) (e.g., increased expression of molecular chaperone BiP/GRP78), the suppression of protein translation mediated by the activation of serine/threonine kinase PERK, and misfolded protein degradation [21]. However, this transient control of accumulation of misfolded proteins can be overcome by sustained ER stress which subsequently leads to caspase-3 activation and apoptosis [22,23]. Overexpression of PKCγ SCA14 mutations triggered ER stress and caspase-3 activation (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). Our results from in vitro neuronal cell culture systems indicate that expression of PKCγ SCA14 mutants initiated protein massive aggregation and ER-stress, only in a small number of mutant cells (less than 10 %, refer to Table 1). However, expression of PKCγ SCA14 mutants caused dysfunction of endogenous PKCγ resulting in open gap junctions which could cause propagation of cell death signals from dying SCA14 mutant cells undergoing ER-stress initiated cell apoptosis to adjacent cells. The consequence of this process is caspase-3 activation and cell death.

SCA14 is a progressive cognitive brain disorder as marked by cerebellar Purkinje neuron degeneration. Purkinje cell loss is largely due to cell apoptosis [24,25]. In SCA14 patients, Purkinje cell damage or death would spread through open gap junctions and this “Bystander” effect would result in spread of neuronal apoptosis [26,27]. This study invites a similar examination of the role of gap junctions in other neurodegenerative disorders and further suggests this as a target for drug development.

PKCγ association with the docking protein 14-3-3 is critical to activation of endogenous wild type PKCγ. Inactive PKCγ is always associated with 14-3-3 protein in the cytosol by binding to the PKCγ C1B domain [14]. This interaction can be competed by synthetic peptide C1B1, the PKCγ binding region for 14-3-3, which, subsequently results in PKCγ activation [14]. The PKCγ SCA14 mutation, H101Y, abolishes the effect of H2O2-induced oxidation within the C1B domain of the mutant PKCγ [19]. Furthermore, the presence of an SCA14 PKCγ mutant abolishes normal function of control of gap junctions by endogenous wild type PKCγ. Thus, we applied synthetic peptide C1B1 to the neuronal HT22 cells overexpressing SCA14 mutants, and found that the peptide can rescue the responses of both endogenous PKCγ and/or SCA14 mutants. This competitive binding of C1B1 peptides to the 14-3-4 docking protein may result in conformational changes within the C1B domain of the PKCγ SCA14 mutants, and/or the interactions between endogenous wild type PKCγ and its SCA14 mutants. This could cause activation of PKCγ SCA14 mutant proteins and/or endogenous PKCγ enzyme, and subsequently inhibition of neuronal cell-to-cell gap junctional communication. The recovery of control of gap junctions can efficiently prevent the passage of cell apoptotic signals from apoptotic SCA14 mutant cells which were initiated by protein aggregation and ER stress. This clearly demonstrates that inhibition of gap junctions could provide future drug targets.

In summary, expression of PKCγ SCA14 mutants triggers ER stress-linked cell apoptosis only in a small number of mutant cells (less than 10 %). However, the cell death signals are propagated to adjacent cells through open gap junctions caused by dysfunction of endogenous PKCγ by the expression of PKCγ SCA14 mutants. C1B1 peptides protect cells from PKCγ SCA14 mutation-induced ER stress and caspase-3-linked apoptosis through inhibition of gap junctions by C1B1 restoration of PKCγ enzyme activity.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Dr. David Schubert of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies for hippocampal HT22 cells. This work was supported by the NIH Grant Number P20 RR016475 from the INBRE Program of the National Center for Research Resources, a grant from the National Organization for Rare Disorders to DL, and a grant NIH EY013421 to DJT

References

- 1.Soong BW, Paulson HL. Spinocerebellar ataxias: an update. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2007;20:438–446. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3281fbd3dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen DH, Brkanac Z, Verlinde CL, Tan XJ, Bylenok L, Nochlin D, Matsushita M, Lipe H, Wolff J, Fernandez M, Cimino PJ, Bird TD, Raskind WH. Missense mutations in the regulatory domain of PKC gamma: a new mechanism for dominant nonepisodic cerebellar ataxia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;72:839–849. doi: 10.1086/373883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vlak MH, Sinke RJ, Rabelink GM, Kremer BP, van de Warrenburg BP. Novel PRKCG/SCA14 mutation in a Dutch spinocerebellar ataxia family: Expanding the phenotype. Mov. Disord. 2006 doi: 10.1002/mds.20851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meller K, Krah K, Theiss C. Dye coupling in Purkinje cells organotypic slice cultures. Develop. Brain Res. 2005;160:101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seki T, Adachi N, Ono Y, Mochizuki H, Hiramoto K, Amano T, Matsubayashi H, Matsumoto M, Kawakami H, Saito N, Sakai N. Mutant protein kinase Cgamma found in spinocerebellar ataxia type 14 is susceptible to aggregation and causes cell death. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:29096–29106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501716200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stevanin G, Hahn V, Lohmann E, Bouslam N, Gouttard M, Soumphonphakdy C, Welter ML, Ollagnon-Roman E, Lemainque A, Ruberg M, Brice A, Durr A. Mutation in the catalytic domain of protein kinase C gamma and extension of the phenotype associated with spinocerebellar ataxia type 14. Arch. Neurol. 2004;61:1242–1248. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.8.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van de Warrenburg BP, Verbeek DS, Piersma SJ, Hennekam FA, Pearson PL, Knoers NV, Kremer HP, Sinke RJ. Identification of a novel SCA14 mutation in a Dutch autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia family. Neurol. 2003;61:1760–1765. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000098883.79421.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verbeek DS, Knight MA, Harmison GG, Fischbeck KH, Howell BW. Protein kinase C gamma mutations in spinocerebellar ataxia 14 increase kinase activity and alter membrane targeting. Brain. 2005;128:436–442. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen DH, Cimino PJ, Ranum LP, Zoghbi HY, Yabe I, Schut L, Margolis RL, Lipe HP, Feleke A, Matsushita M, Wolff J, Morgan C, Lau D, Fernandez M, Sasaki H, Raskind WH, Bird TD. The clinical and genetic spectrum of spinocerebellar ataxia 14. Neurol. 2005;64:1258–1260. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000156801.64549.6B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yabe I, Sasaki H, Chen DH, Raskind WH, Bird TD, Yamashita I, Tsuji S, Kikuchi S, Tashiro K. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 14 caused by a mutation in protein kinase C gamma. Arch. Neurol. 2003;60:1749–1751. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.12.1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alonso I, Costa C, Gomes A, Ferro A, Seixas AI, Silva S, Cruz VT, Coutinho P, Sequeiros J, Silveira I. A novel H101Q mutation causes PKCgamma loss in spinocerebellar ataxia type 14. J. Human Genet. 2005;50:523–529. doi: 10.1007/s10038-005-0287-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klebe S, Durr A, Rentschler A, Hahn-Barma V, Abele M, Bouslam N, Schols L, Jedynak P, Forlani S, Denis E, Dussert C, Agid Y, Bauer P, Globas C, Wullner U, Brice A, Riess O, Stevanin G. New mutations in protein kinase Cgamma associated with spinocerebellar ataxia type 14. Ann. Neurol. 2005;58:720–729. doi: 10.1002/ana.20628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fahey MC, Knight MA, Shaw JH, Gardner RJ, du Sart D, Lockhart PJ, Delatycki MB, Gates PC, Storeym E. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 14: study of a family with an exon 5 mutation in the PRKCG gene. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2005;76:1720–1722. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.044115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen TA, Takemoto LJ, Takemoto DJ. Inhibition of gap junction activity through the release of the C1B domain of protein kinase Cgamma (PKCgamma) from 14-3-3: identification of PKCgamma-binding sites. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:52714–52725. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403040200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frantseva J. Ischemia-induced brain damage depends on specific gap-junctional coupling. J. Cerebral. Blood Flow & Metab. 2002;22:453–462. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200204000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakase T, Fushiki S, Naus CC. Astrocytic gap junctions composed of connexin 43 reduce apoptotic neuronal damage in cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2003;34:1987–1993. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000079814.72027.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Pina-Benabou MH, Szostak V, Kyrozis A, Rempe D, Uziel D, Urban-Maldonado M, Benabou S, Spray DC, Federoff HJ, Stanton PK, Rozental R. Blockade of gap junctions in vivo provides neuroprotection after perinatal global ischemia. Stroke. 2005;36:2232–2237. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000182239.75969.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin D, Shanks D, Prakash O, Takemoto DJ. Protein kinase C gamma mutations in the C1B domain cause caspase-3-linked apoptosis in lens epithelial cells through gap junctions. Exp. Eye Res. 2007;85:113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin D, Takemoto DJ. Oxidative activation of protein kinase Cgamma through the C1 domain. Effects on gap junctions. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:13682–13693. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407762200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cumming RC, Andon NL, Haynes PA, Park M, Fischer WH, Schubert D. Protein disulfide bond formation in the cytoplasm during oxidative stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:21749–21758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312267200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siman R, Flood DG, Thinakaran G, Neumar RW. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced cysteine protease activation in cortical neurons: effect of an Alzheimer's disease-linked presenilin-1 knock-in mutation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:44736–44743. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104092200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perez-Sala D, Mollinedo F. Inhibition of N-linked glycosylation induces early apoptosis in human promyelocytic HL-60 cells. J. Cell Physiol. 1995;163:523–531. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041630312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang JY, Korolev VV. Specific toxicity of tunicamycin in induction of programmed cell death of sympathetic neurons. Exp. Neurol. 1996;137:201–211. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1996.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goswami J, Martin LA, Goldowitz D, Beitz AJ, Feddersen RM. Enhanced Purkinje cell survival but compromised cerebellar function in targeted anti-apoptotic protein transgenic mice. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2005;29:202–221. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abeliovich A, Chen C, Goda Y, Silva AJ, Stevens CF, Tonegawa S. Modified hippocampal long-term potentiation in PKC gamma-mutant mice. Cell. 1993;75:1253–1262. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90613-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farahani R, Pina-Benabou MH, Kyrozis A, Siddiq A, Barradas PC, Chiu FC, Cavalcante LA, Lai JC, Stanton PK, Rozental R. Alterations in metabolism and gap junction expression may determine the role of astrocytes as “good samaritans” or executioners. Glia. 2005;50:351–361. doi: 10.1002/glia.20213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson RJ, Zhou N, MacVicar BA. Ischemia opens neuronal gap junction hemichannels. Science. 2006;312:924–927. doi: 10.1126/science.1126241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]