Abstract

Assessments of personality disorder (PD) and conduct disorder (CD) in a random community sample at mean age 13 were employed to predict subsequent substance abuse disorder (SUD), trajectories of symptoms of abuse or dependence on alcohol, marijuana, or other illicit substances, and hazard of initiating marijuana use over the subsequent decade. Personality disorders and conduct disorder were associated with diagnoses and symptoms of SUDs in every model and their effects were independent of correlated family risks, participant sex, and other Axis I disorders. Specific elevated PD symptoms in early adolescence were also associated with differential trajectories of already initiated SUD symptoms as well as elevated risk for future onset of SUD symptoms. For several models the greatest of these effects were shown for borderline PD and for conduct disorder, the predecessor of adult antisocial PD. Passive-aggressive PD also showed independent elevation effects on substance use symptoms for alcohol and marijuana. Analyses over 30 years suggest that Cluster B PD (borderline, histrionic, narcissistic) are independent risks for development of SUD and warrant clinical attention.

Keywords: Comorbidity, Adolescents, Dependence, Personality Disorders, Conduct Disorders, Trajectories, Longitudinal Research

1. Introduction

Numerous studies have examined the comorbidity of substance use disorders (SUDs) and Axis II personality disorders (PDs) in clinical and nonclinical samples of adults (Ball et al., 1997; DeJong et al., 1993; Driessen et al., 1998; Grilo, Martino, Walker, Becker, Edell, & McGlashan, 1997; Johnson et al., 1996; Morgenstern et al., 1997; Nace, Davis, & Gaspari, 1991; O’Boyle, 1993; Rounsaville et al., 1998; Trull, Waudby, & Sher, 2004; Verheul et al., 1998; Weiss et al., 1993). In addition to well-established links between antisocial PD and SUDs (Regier et al., 1990), researchers have recently documented reliable associations between borderline PD and SUDs (see Trull, Sher, Minks-Brown, Durbin, & Burr, 2000, for a review). Even after controlling for effects of antisocial PD and other co-occurring PDs, borderline PD remained significantly associated with higher rates of substance abuse in adults in an outpatient psychiatric sample (Skodol, Oldham, & Gallaher, 1999).

Borderline PD typically manifests in affective instability and mood reactivity, intense and unstable interpersonal relationships, unstable identity and self-image, and a recurrent pattern of impulsive and potentially self-destructive behavior. There are numerous ways to explain why borderline PD would be associated with increased rates of SUDs. Deficits in affect regulation and impulse control that characterize borderline PD may also predispose people to SUDs. Alternatively, early problems with drugs and alcohol in adolescence may undermine subsequent personality development. It is also possible that shared genetic factors or family risks may explain part of the co-occurrence between borderline PD and SUDs. Parental PD and substance abuse are known to increase risk for borderline PD in early adolescence (Guzder, Paris, Zelkowitz, & Feldman, 1999; Johnson, Brent et al., 1995) and the intergenerational transmission of SUDs is well documented (Luthar, Merikangas, & Rounsaville, 1993; Merikangas et al., 1998; Miles et al., 1998). For borderline PD, however, the limited genetic evidence currently available suggests that heritable influences on these personality traits are separate from those associated with alcohol abuse (Jang, Vernon, & Livesley, 2000). Thus, clarifying the developmental factors that may account for associations observed between borderline PD and SUDs is a goal of the current study.

Little is known about comorbidity between SUDs and PDs during adolescence other than well-documented links between SUDs and conduct disorder in adolescence and antisocial PD in adulthood (Hesselbrock, 1986; Robins, 1966). Previous studies of drug and alcohol abuse in adolescence have not systematically assessed PDs because little was known about the manifestation and meaning of Axis II disorders before adulthood. As evidence has documented that significant personality disturbances occur even in early adolescence (Bernstein, Cohen, Velez, Schwab-Stone, Siever, & Shinsato, 1993; Johnson, Cohen, Kasen, Skodol, & Brook, 2000; Johnson, Cohen, Skodol, Oldham, Kasen, & Brook, 1999; Kasen, Cohen, Skodol, Johnson, & Brook, 1999; Rey, Morris-Yates, Singh, Andrews, & Stewart, 1995; Rey, Singh, Morris-Yates, & Andrews, 1997), it has become increasingly important to assess comorbidity between SUDs and PDs to increase understanding of etiology and course issues.

Adolescent SUDs and co-occurring Axis II disorders have been investigated in inpatient psychiatric samples (Grilo, Becker, Walker, Levy, Edell, & McGlashan, 1995; Grilo, Martino, Walker, Becker, Edell, & McGlashan, 1997). When comparing adolescents with and without SUDs for co-occurring Axis I disorders and Axis II disorders, Grilo et al. (1995) reported that conduct disorder and borderline personality disorder were diagnosed more frequently in patients with SUDs. In a separate study, borderline PD was associated with SUD diagnoses in adolescent inpatients only when substance abuse co-occurred with conduct disorder (Grilo, et al., 1997). This finding underscores the importance of taking comorbid conduct disorder into account when assessing PD-SUD comorbidity in adolescents.

Findings based on adolescent patients may be influenced by ascertainment bias (Berkson, 1946) that overestimates general comorbidity rates in non-treatment populations. However, adolescents with borderline PD in a non-patient sample of first-year college students also were more likely than those without any PD to be heavy users of alcohol and marijuana (Johnson, Hyler, Skoldol, Bornstein, & Sherman, 1995). Although this study of non-patient adolescents was not limited by ascertainment bias, it did not control for conduct/antisocial disorder or other PDs that often co-occur with borderline PD, thus leaving it uncertain whether borderline PD is linked with SUDs above and beyond their associations with other psychiatric disorders.

Research on adolescent PDs and SUDs is mostly based on cross-sectional data. Thus very little is known about the effects of early PDs on the development and course of SUDs in later adolescence and adulthood. Much more is known about the relationship of adolescent conduct disorder with current and subsequent substance use and SUDs. Retrospectively reported data from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study suggest that conduct disorder symptoms in childhood predicted higher rates of SUD in adolescence (Robins & Price, 1991). Data from the National Longitudinal Study of Youth also suggest that antisocial behavior in early adolescence predicted substance use in late adolescence (Windle, 1990). Other studies using a range of assessment methods have found that conduct disorder tends to precede SUD (Boyle, Offord, Racine, Szatmari, Gleming, & Links, 1992; Gittelman, Manuzza, Shenker, & Bonagura, 1985; Kandel, Kessler, & Margulies, 1978), perhaps partly because the age of onset and of peak prevalence are younger for conduct disorder than for SUD.

Conduct disorder (CD) is a unique childhood disorder in the current diagnostic system because it is not included as an adult Axis I disorder. Rather, similar behaviors and attitudes in adulthood are considered a personality disorder (antisocial personality disorder), and thus excluded from Axis I despite the current diagnostic requirement of a history of conduct disorder. Clearly, it is reasonable to think of adolescent CD as essentially an early manifestation of PD although many adolescents meeting CD diagnostic criteria do not subsequently meet antisocial PD criteria. Nevertheless, it remains unclear whether borderline PD or any other PDs in early adolescence predict subsequent SUDs independently of conduct disorder.

To address these issues the current study employed data from a longitudinal cohort on which PD and SUD have been assessed since early adolescence to focus on how early PDs relate to prospective levels and changes in SUD symptoms over the subsequent 20 years from adolescence to mid-adulthood. In this study Axis II disorders were assessed in most of the cohort before the period when most substance abuse typically begins between ages 15 and 19 (Burke, Burke, Regier, & Rae, 1990). Thus it was also possible to determine whether the course of early onset substance abuse problems was influenced by the presence of early personality disorder and whether PD preceded onset of such problems.

2. METHODS

2.1 Participants and study procedures

These data come from a residentially-based random sample of children residing in one of two upstate New York counties who had been assessed for Axis I and II disorders first in 1983. The sample was based on an earlier study using maternal interviews to determine a range of problems of age 1 to 10 offspring potentially associated with area-specific social indicators (Kogan, Smith, & Jenkins, 1977). Sample members who could be located at follow-up in 1983 were supplemented with 54 newly sampled participants recruited from areas of urban poverty to replace those from the previous sample lost when neighborhoods were razed in connection with urban renewal. With this supplement the 1983 sample closely represented demographic characteristics of the geographic area of recruitment (see nypisys.cpmc.columbia.edu/childcom/for details on sampling and sample retention) Follow-up interviews of both mothers and youths with an expanded protocol were conducted in 1983 (T2), 1985–1986 (T3), and 1991–1994 (T4), when youths were mean (SD) ages 13.7 (2.6) years, 16.4 (2.8) years and 22.4 (2.8) years, respectively. Retention rate has been over 95% until the most recent mean age 33.2 (2.9) follow-up of 680 of the 796 surviving participants (85%). At all interviews, consent was obtained from all participants according to IRB standards, and a NIH Certificate of Confidentiality exists for these data.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Axis I disorders

Substance use disorders, conduct disorder, and all other Axis I disorders were assessed with the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-I; Costello, Edelbrock, Duncan, & Kalas, 1984). Beginning in 1983 we administered the DISC-I separately to children and a parent, usually their mothers. Home interviews were carried out by two interviewers who were blind to the responses of the other respondent and to any prior data. When first assessed with the DISC-I, children ranged in age from nine to 18.

Data from parent and child were combined by computer algorithms in two ways. First, we created continuous scales for each Axis I disorder defined by Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association (American Psychiatric Association, 1987) by summing responses to disorder-specific questions on symptoms and associated impairment for each respondent. By and large these scales have acceptable internal consistency reliability, ranging from .6 to over .9 (Cohen & Cohen, 1996), despite the absence of concern about such reliability in the definition of these disorders. DSM-III-R diagnoses for adolescents were made based on criteria met by either youth or parent report on the DISC-I but also requiring that the sum of the mother and adolescent symptom scales for the disorder be at least one standard deviation above the sample mean. This decision to consider either respondent’s symptom indication as positive is consistent with the consensus of the field that sensitivity is thereby ensured (Bird, Gould, & Staghezza, 1992), while the use of the additional criterion based on the pooled scales enhances the specificity of the diagnoses. DISC-I algorithms thus yielded diagnoses for SUDs that were used as dependent variables at mean ages 16.4 and 22.2 in our multilevel logistic analyses. As indicated below, we used conduct disorder diagnoses at mean age 13.7 as a predictor variable. We also used a dichotomous predictor indicating the presence of any other Axis I diagnoses (i.e., excluding conduct disorder and SUDs, thus primarily anxiety and depression) as a control variable.

In the adult assessments at mean age 22.4 we altered the DISC to increase its appropriateness for adult respondents and collected Axis I diagnostic information only from the offspring. At mean age 33.2 we employed the SCID-IV interview for Axis I disorders.

2.2.2 Axis II disorders

In 1983 no developed instruments existed for assessing PD before adulthood. We created such an instrument by adapting items from the PDQ questionnaire for adults (Hyler, Rieder, Spitzer, & Williams, 1982; Hyler, Reider, Williams, Spitzer, Hendler & Lyons, 1988) and by selecting appropriate items from other existing scales or writing age appropriate items when necessary (Bernstein et al., 1993; Bernstein, Cohen, Skodol, Bezirganian, & Brook, 1996). Although many criteria used information from both respondents, most information came from the offspring interview. Thus, when the mother was the only informant for a given assessment we have excluded those children from the analyzed sample. Some PD diagnostic criteria are intrinsically difficult to assess by self-report, and we relied on the parental respondent for these when assessing PDs at T2, T3, and T4.

2.2.3 Substance abuse disorder symptoms

For this study we used symptom scales based on offspring only reports to assess alcohol abuse/dependence and marijuana abuse/dependence consistent with DSM criteria. The use of youth reports only was chosen in keeping with evidence both from this study and from others that parents are not always aware of offspring substance use and abuse and also because these measures were not available from a parent once the participants reached adulthood. These scales were subjected to a logistic function transformation in order to normalize sufficiently for use in the employed statistical programs and a zero value indicates the total absence of such symptoms.

2.2.4 Parental substance abuse

Parental respondents in the 1983, 1986, and 1992 interviews were asked in separate items whether the child’s mother had any problems with drinking or drugs, and identical questions were asked about the child’s father. These four items were used to create a simple dichotomous variable indicating the presence or absence of parental substance abuse. Because it is plausible that parental substance abuse may contribute to offspring PD and CD as well as to offspring substance abuse/dependence this variable was employed as a control variable in the analyses.

2.2.5 Demographic control variables

Family socioeconomic status was measured as a standardized sum of standardized parental education, occupational status, and family income. Because this variable is related to both offspring PD and CD and offspring substance use it is included as a control variable. Gender was also included as a control variable and investigated with regard to potential influence on the analyze relationships between adolescent PD and SUD diagnoses, we contrasted participants with PD diagnoses at mean age 13.7 with a comparison group (n=567) of participants without any PD.

2.3 Analytic plan

In each of these analyses the primary predictors are the early adolescent PDs assessed in 1983 (T2) when the cohort was on average 13.7 years old. In the first set of these analyses, we used multilevel logistic regression equations to estimate the associated increase in the odds of SUD diagnoses covering assessed ages between age 9 (the youngest at T2) and age 27 (the oldest at T4), net of the effects of control variables also included in the model. The SAS GLIMMIX macro was used to fit the multilevel logistic regression models (Cohen et al., 2000; Littell et al., 1996).

The second set of analyses examined the association between the age of first marijuana use and early adolescent PD. Survival analyses were employed to calculate the average age of first time to use marijuana for youth with each PD (or conduct disorder) in comparison to those without PDs using the Kaplan-Meier method. (Age-of-onset data for alcohol use and other SUDs were not recorded and thus could not be analyzed here.) In order to exclude effects potentially attributable to common causes or correlates of PD and SUDs or SUD symptoms, all analyses include as covariates sex, race, family socioeconomic status, parental substance use, and other Axis I disorders.

The next analyses addressed developmental questions more directly by employing multilevel models to assess patterns of change in self-reported symptoms of alcohol and marijuana abuse and dependence. In aggregate these analyses tested whether there were significant differences in the trajectories of SUD symptoms between ages 12 (the youngest participants in 1986) and 38 (the oldest in 2003) associated with diagnostic criteria for each DSM-IV PD in the early adolescent (1983) assessment. The two sets of analyses used the SAS PROC MIXED program (Littell et al., 1996) and employed all covariates, including age and substance abuse/dependence symptoms in the 1983 assessment as control variables. In addition, they examine the interaction of early adolescent PD symptoms with early SUD symptoms. This test determines whether early personality disorder may alter the course-effects of early onset SUD symptoms.

In these longitudinal multilevel models participant measures repeated over time are the basic dependent variables, comparable to a single variable in ordinary regression analyses. Instead of accounting for the variance in a single dependent variable, these methods account for the variance in functions of the set of variables; here the variance in participant means, linear slopes or trajectories, and residual individual variance around their own trajectories. This set of variance indicators is considered the basic “random” data, just as in ordinary regression “random” variation of a single variable is to be accounted for. The first step in these analyses examines the between participant differences (“random effects”) in mean level, and in linear and nonlinear (quadratic) age changes. For alcohol-use symptoms the dramatic normative age curve so dominated the variance that the estimates of random (between participant) variance in linear and quadratic slopes were not statistically significant. If there had been evidence of significant variance in these parameters we would have reported those random estimates in the table.

This model was then the basis for examination of the fixed (average) effects of linear and quadratic age change (the basic model), and those of the covariates (Model 1). Following this basic model, we fit a series of models for each PD diagnosis that test both main effects and interactive effects of PD on the influence of other variables on subsequent alcohol or marijuana SUD symptom means or trajectories. As noted in the following section, these analyses were carried out in two sets. The first examined the associations of early adolescent PD with the level and course of SUD symptoms from early adolescence to young adulthood. The second set of analyses attempted to enable stronger causal inferences by including early adolescent SUD symptoms as a predictor of subsequent mean and trajectory of SUD symptoms over the following 20 years.

3. Results

3.1 Prevalence of personality disorders at early adolescence and associations with covariates and current symptoms of SUD

Table 1 presents the means of each of the control variables and their correlations with early PD, SUDs, and symptoms of alcohol and marijuana use disorders. At mean age 13.7, 182 youths (24.3%) met criteria for at least one PD. Co-occurring PD diagnoses were frequent in this community sample; on average youths with PD received nearly two (1.84) diagnoses per person. As noted in earlier reports (Bernstein, et al.,1996; Johnson et al, 2000), the high PD prevalence observed in early adolescence declines linearly with age but nevertheless maintains the same rank order correlation of symptom level over time as is shown in adulthood. The most prevalent Axis II disorders were histrionic PD (6.1%), narcissistic PD (5.3%), paranoid PD (4.7%), borderline PD (4.7%), passive-aggressive PD (4.4%), and obsessive-compulsive PD (4.1%). In contrast, schizoid PD, schizotypal PD, avoidant PD, dependent PD, and conduct disorder were each reported for less than 4.0% of the participants.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics and personality disorder at mean age 13.7 and correlations of control variables with sample characteristics (N = 749)

| Disorder group | Prevalence % | Age 1983 | Male | White vs nonwhite | Parental SUD | Axis I Disorder |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entire sample | 13.7 | .50 | .91 | |||

| No PD | 75.7 | |||||

| Paranoid PD | 4.7 | .005 | .049 | −.128 | .048 | .232 |

| Schizoid PD | 2.0 | −.085 | .048 | −.053 | .056 | .015 |

| Schizotypal PD | 2.5 | −.013 | −.008 | −.037 | −.010 | .206 |

| Borderline PD | 4.7 | .033 | −.094 | −.083 | .043 | .298 |

| Histrionic PD | 6.1 | −.076 | .012 | −.111 | .008 | .205 |

| Narcissistic PD | 5.3 | .004 | .013 | −.089 | .057 | .283 |

| Avoidant PD | 3.5 | −.037 | −.014 | −.091 | .061 | .293 |

| Dependent PD | 3.9 | −.059 | −.048 | −.157 | .030 | .175 |

| Obs-Comp PD | 4.1 | .018 | −.033 | −.027 | .075 | .127 |

| Pass-Agg PD | 4.4 | −.013 | −.006 | −.157 | .050 | .295 |

| Conduct Disord | 3.9 | −.002 | .115 | −.150 | .100 | .101 |

| Alcohol abuse or dependence | 5.6 | |||||

| Marijuana abuse or dependence | 1.2 | |||||

| Illicit drug abuse or dependence | .8 | |||||

| Any SUD | 6.1 |

Note: In these analyses we used conduct disorder at the severe level rather than moderate which would have been a prevalence of 11%. This choice did not affect substantive interpretations: moderate CD was more stable and predictive over a short interval whereas severe CD was more stable and predictive over the longer interval. Axis I disorders as measured here did not include CD.

3.2 Changes in SUD diagnoses from early adolescent to young adulthood

Prevalence estimates for SUDs in Table 1 combine diagnoses for abuse and dependence of a given substance. In the assessment at mean age 13.7 (SD = 2.6), 6.1% of the participants reported at least one SUD (alcohol, marijuana, or other illicit drug), and 8.0% and 19.3% of the participants subsequently met criteria for a SUD at mean age 16.4 and 22.4, respectively. Of those reporting any SUD at T2, 20 out of 46 participants (43.5%) had at least one co-occurring PD. This rate is significantly higher than the 23.0% observed in the group without SUD (χ2 = 9.80, p < .01).

Table 2 summarizes estimates from multilevel logistic regression analyses of SUD that controlled for potential effects of age, sex, race, family SES, parental substance use, and Axis I disorders. In these analyses participants with schizotypal PD, borderline PD, narcissistic PD, passive-aggressive PD, or conduct disorder at mean age 13.7 had significantly elevated rates of SUD between early adolescence and young adulthood. Odds Ratios (OR) ranged from 5.82 to 12.30 for those with PDs in comparison to those without PDs or conduct disorder. Tests for the independent effects of specific PDs in these predictions were not carried out because of insufficient statistical power due to high rates of comorbidity between PDs and low rates of SUD.

Table 2.

Odds ratios for a substance use disorder between adolescence and young adulthood for those with personality or conduct disorder in comparison to those without such disorders (N=749)

| Predictor | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| None of these disorders (reference) | 1.00 | ||

| Paranoid PD | 4.10 | 0.63 – 26.84 | 0.14 |

| Schizoid PD | 0.10 | 0.00 – 3.90 | 0.22 |

| Schizotypal PD | 9.43 | 1.11 – 80.16 | < .05 |

| Borderline PD | 6.19 | 1.10 – 34.92 | <.05 |

| Histrionic PD | 2.44 | 0.52 – 11.47 | 0.26 |

| Narcissistic PD | 5.82 | 1.17 – 28.82 | <.05 |

| Avoidant PD | 1.73 | 0.21 – 14.15 | 0.61 |

| Dependent PD | 1.31 | 0.19 – 9.13 | 0.78 |

| Obsessive-Compulsive PD | 0.91 | 0.96 – 6.30 | 0.92 |

| Passive-Aggressive PD | 8.15 | 1.44 – 46.11 | < .05 |

| Conduct Disorder | 12.30 | 1.15 – 131.63 | < .05 |

Note: Each disorder was employed as a predictor in a separate logistic regression model with the comparison group of those without PD or conduct disorder (n=567) including as covariates age, sex, socioeconomic status, race, parental substance use, and any other Axis I disorder.

3.3 The onset of marijuana use

Table 3 shows the association of early adolescent PD and the age of initial marijuana use from preadolescence and early adolescence to adulthood. Average age of first time to use marijuana was 18.6 for the group without PDs. Average age of first use of marijuana was significantly earlier for subjects with paranoid PD (14.9), borderline PD (16.5), and conduct disorder (13.6) than those without PD as indicated in the Kaplan-Meier estimates.

Table 3.

Age of first marijuana use associated with early adolescence personality disorder (PD): Cox regression analyses (N = 749)

| Predictor | First age (SE) | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No PD | 18.63 (0.27) | |||

| In separate models | ||||

| Paranoid PD | 14.86 (0.55) | 1.73 | 1.02 – 2.93 | < .05 |

| Schizoid PD | 15.93 (0.36) | 0.84 | 0.43 – 1.64 | 0.61 |

| Schizotypal PD | 15.36 (0.84) | 1.75 | 0.99 – 3.08 | 0.05 |

| Borderline PD | 16.51 (1.01) | 2.22 | 1.43 – 3.46 | <.01 |

| Histrionic PD | 16.09 (0.56) | 1.35 | 0.93 – 1.97 | 0.12 |

| Narcissistic PD | 15.40 (0.57) | 1.35 | 0.88 – 2.05 | 0.17 |

| Avoidant PD | 15.04 (0.46) | 1.16 | 0.68 – 1.98 | 0.59 |

| Dependent PD | 16.17 (0.73) | 1.26 | 0.78 – 2.03 | 0.35 |

| Obsessive-Compulsive PD | 15.68 (0.38) | 0.93 | 0.59 – 1.49 | 0.77 |

| Passive-Aggressive PD | 15.45 (0.73) | 1.55 | 0.93 – 2.58 | 0.09 |

| Conduct Disorder | 13.64 (0.65) | 3.32 | 1.80 – 6.11 | <.01 |

| Simultaneous Model of all PDs | ||||

| Borderline PD | 1.73 | 1.07 – 2.79 | < .05 | |

| Conduct Disorder | 2.59 | 1.47 – 4.55 | <.01 | |

Note: Separate models compare each PD and conduct disorder with the group without PD (n=567). The simultaneous model included all PDs; only statistically significant effects of PDs are reported.

Survival analyses were carried out with Cox regression analyses in which we included statistical covariates used in the earlier analyses. In these analyses, hazard ratios are similar to ORs in logistic regression, in that they are expressions of risk in comparison to a reference group. In this case the hazard indicates the odds that marijuana use will be initiated by participants in the group who have not already initiated it at an earlier age in comparison to the corresponding odds for a reference group. Significant effects were found for those with paranoid PD, borderline PD, and conduct disorder when compared with participants without any PD or conduct disorder. At any given point over this age period, those with paranoid PD in early adolescence had 1.73 times the hazard of initiating marijuana use than adolescents without PD or conduct disorder. Borderline PD in early adolescence was associated with 2.22 times the hazard of initiating marijuana use, while adolescents with conduct disorder had 3.32 times the hazard of initiating marijuana use over this period, each in comparison with adolescents without PD or conduct disorder.

Cox regressions examining independent hazard ratios for initiating marijuana use were also carried out and included all PDs and conduct disorder in the same model. Early adolescent borderline PD and conduct disorder were independently associated with elevated hazard ratios for the onset of marijuana use. Paranoid PD did not show a significant independent effect. At any given age, adolescents with borderline PD who had not yet begun marijuana use had 1.73 times the hazard for marijuana initiation observed in the reference group and those with conduct disorder had 2.59 times the hazard of initiating marijuana use.

3.4 Symptoms of SUD between ages 12 and 25 following earlier assessment of PD or CD

The next analyses used multilevel change models to test whether PD and conduct disorder at T2 were associated with age changes in SUD symptom levels over time. All analyses included the covariates noted above as well as linear and quadratic effects of age at each assessment. Analyses first tested whether groups defined by specific PD diagnoses and the comparison group without any PD showed significant differences in patterns of change in SUD symptoms over time. A second set of analyses tested the independence of each PD’s associations with each SUD scale by including the other PDs in the same model.

3.5 Alcohol abuse/dependency symptoms

As reported in Table 4, alcohol abuse/dependency symptoms in the group without PD (n=567) increased linearly about 0.071 average unit per year combined with a 0.004 unit deceleration in this increase after age 17 (the age around which all ages were centered). Youths diagnosed with seven out of ten PDs had statistically higher mean symptoms levels over time when compared with those without any PD. Specifically, participants with paranoid PD, schizotypal PD, borderline PD, narcissistic PD, histrionic PD, avoidant PD, passive-aggressive PD, and conduct disorder all had higher levels of alcohol abuse/dependence than those without any PD. For youth with schizotypal PD, the increase in SUD symptoms was 0.034 units per year less than that of the group without PD, indicating that the high mean level of alcohol disorder symptoms was present at an early age and did not increase as rapidly as in the reference group. Those with narcissistic PD showed a very elevated mean with decelerated increase with age in comparison with those without PD.

Table 4.

Symptoms of alcohol use disorder associated with early personality disorder (PD) for each trajectory parameter in comparison to those without PD (N = 749)

| Predictor | Mean Level | Linear Age Change | Quadratic Age Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| No PD | 0.522** | 0.071** | −0.004** |

| In separate models | |||

| Paranoid PD | 0.159* | 0.005 | −0.004 |

| Schizoid PD | −0.171 | −0.030 | 0.001 |

| Schizotypal PD | 0.235** | −0.034* | −0.004 |

| Borderline PD | 0.260** | −0.022 | −0.003 |

| Histrionic PD | 0.148** | 0.008 | −0.002 |

| Narcissistic PD | 0.247** | 0.021 | −0.006** |

| Avoidant PD | 0.162* | −0.010 | −0.003 |

| Dependent PD | 0.049 | −0.021 | −0.002 |

| Obsessive-Compulsive PD | −0.043 | −0.020 | −0.001 |

| Passive-Aggressive PD | 0.241** | −0.014 | −0.002 |

| Conduct Disorder | 0.297** | 0.015 | −0.001 |

| Simultaneous Model of all PDs | |||

| Borderline PD | 0.152** | −0.030** | |

| Histrionic PD | 0.104* | ||

| Narcissistic PD | 0.123* | ||

| Passive-Aggressive PD | 0.145* | ||

| Conduct Disorder | 0.207** | ||

Note: All parameter entries are maximum likelihood regression estimates fitted using SAS PROC MIXED and including all covariates. Age was centered by 17. Separate models compare each PD and conduct disorder with the group without PD (n=567). The simultaneous model included all PDs and reports only statistically significant effects of PDs.

p < .05;

p < .01.

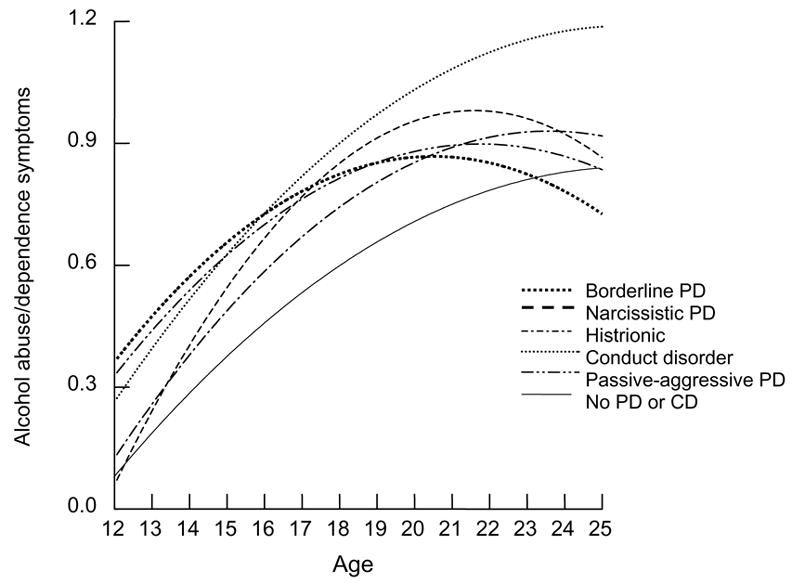

Table 4 also summarizes analyses that included all PDs and conduct disorder simultaneously in the same multilevel model, thereby adjusting for the effects of co-occurring PDs along with all the other controls specified above. These models identify the independent association of each separate PD with the change in symptom level over time net of other PDs and conduct disorder. As depicted in Figure 1, borderline PD, narcissistic PD, histrionic PD, passive-aggressive PD, and conduct disorder in early adolescence were all found to be independently associated with significantly elevated mean symptoms of alcohol abuse/dependency across the age range. Borderline PD was independently associated with a 0.03 unit smaller linear increase in alcohol use disorder symptoms per year in comparison with those without disorder. As shown in Figure 1, the effect of early adolescent borderline PD on these symptoms dissipated by about age 23. Aside from differences in overall alcohol symptom levels, other PDs and conduct disorder did not show a significantly different trajectory from the no disorder group over time.

Figure 1.

Trajectories of alcohol abuse and dependency symptoms by adolescent PD diagnosis

3.6 Marijuana abuse/dependency symptoms

For the group without PD (n=567), marijuana abuse/dependency symptoms increased linearly about 0.026 unit per year combined with a 0.001 unit deceleration in this increase (Table 5). Compared with the group without PD, statistically higher mean symptom levels were found across the age range for adolescents with schizotypal, borderline, histrionic, avoidant, and passive-aggressive PD, as well as those with conduct disorder. No significant differences in linear age change in symptoms were identified between those with PD and those without PD. However, adolescents with histrionic and avoidant PD showed decelerated age changes compared to those adolescents without PD.

Table 5.

Symptoms of marijuana use disorder associated with personality disorder (PD) for each trajectory parameter in comparison to those without PD (N = 749)

| Predictor | Mean Level | Linear Age Change | Quadratic Age Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| No PD | 0.319** | 0.026** | −0.001** |

| In separate models | |||

| Paranoid PD | 0.049 | −0.004 | −0.001 |

| Schizoid PD | −0.074 | −0.018 | −0.002 |

| Schizotypal PD | 0.129* | −0.011 | −0.002 |

| Borderline PD | 0.117** | −0.014 | −0.001 |

| Histrionic PD | 0.099** | 0.000 | −0.002* |

| Narcissistic PD | 0.070 | −0.009 | −0.002 |

| Avoidant PD | 0.227** | 0.003 | −0.005** |

| Dependent PD | 0.054 | 0.001 | −0.002 |

| Obsessive-Compulsive PD | 0.005 | −0.007 | −0.021 |

| Passive-Aggressive PD | 0.160** | −0.003 | −0.001 |

| Conduct Disorder | 0.193** | 0.002 | −0.001 |

| Simultaneous Model of all PDs | |||

| Borderline PD | 0.070* | ||

| Passive-Aggressive PD | 0.120** | ||

| Conduct Disorder | 0.143** | ||

Note: All parameter entries are maximum likelihood regression estimates fitted using SAS PROC MIXED and including all covariates. Age was centered by 17. Separate models compare each PD and conduct disorder with the group without PD (n=567). The simultaneous model included all PDs and reports only statistically significant effects of PDs.

p < .05;

p < .01.

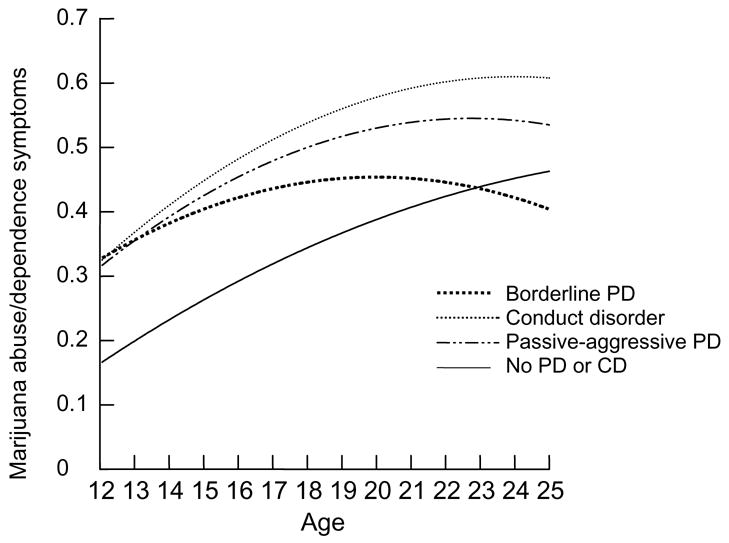

The independent associations of early adolescent PDs and symptoms of marijuana abuse/dependency from early adolescence to adulthood are presented in the final model in Table 5 and depicted in Figure 2. After adjusting for the effects of all other PDs in early adolescence, borderline PD, passive-aggressive PD, and conduct disorder were each independently associated with statistically higher mean symptoms of marijuana use disorder across the age range.

Figure 2.

Trajectories of marijuana abuse and dependency symptoms by adolescent PD diagnosis

3.7 Illicit drug use abuse/dependency symptoms

For the group without PD (n=567), symptoms of illicit drug use other than marijuana increased linearly by about 0.064 unit per year combined with a 0.003 unit acceleration in this increase (Table 6). Compared with the young adolescents without PD, statistically higher mean symptom levels for illicit SUD were found across the age range for adolescents with borderline PD, narcissistic PD, histrionic PD, avoidant PD, and conduct disorder. Young adolescents with borderline PD, however showed an annual increase in symptoms that was 0.025 unit per year less than that of the reference group. No significant group differences in quadratic age change were found.

Table 6.

Symptoms of illicit drug use disorder (excluding marijuana) associated with personality disorder (PD) for each trajectory parameter in comparison to those without PD (N = 749)

| Predictor | Mean Level | Linear Age Change | Quadratic Age Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| No PD | 0.576** | 0.064** | 0.003** |

| In separate models | |||

| Paranoid PD | −0.001 | 0.003 | 0.000 |

| Schizoid PD | 0.073 | 0.010 | 0.000 |

| Schizotypal PD | 0.084 | −0.030 | 0.003 |

| Borderline PD | 0.097* | −0.025* | 0.000 |

| Histrionic PD | 0.144** | 0.010 | −0.002 |

| Narcissistic PD | 0.101* | 0.009 | −0.003 |

| Avoidant PD | 0.138* | 0.002 | −0.002 |

| Dependent PD | 0.070 | −0.007 | −0.002 |

| Obsessive-Compulsive PD | 0.043 | −0.001 | 0.001 |

| Passive-Aggressive PD | 0.041 | −0.019 | 0.003 |

| Conduct Disorder | 0.200** | −0.016 | 0.000 |

| Simultaneous Model of all PDs | |||

| Histrionic PD | 0.077* | ||

| Conduct Disorder | 0.154** | −0.020* | |

Note: All parameter entries are maximum likelihood regression estimates fitted using SAS PROC MIXED and including all covariates. Age was centered by 17. Separate models compare each PD and conduct disorder with the group without PD (n=567). The simultaneous model included all PDs and reports only statistically significant effects of PDs.

p < .05;

p < .01.

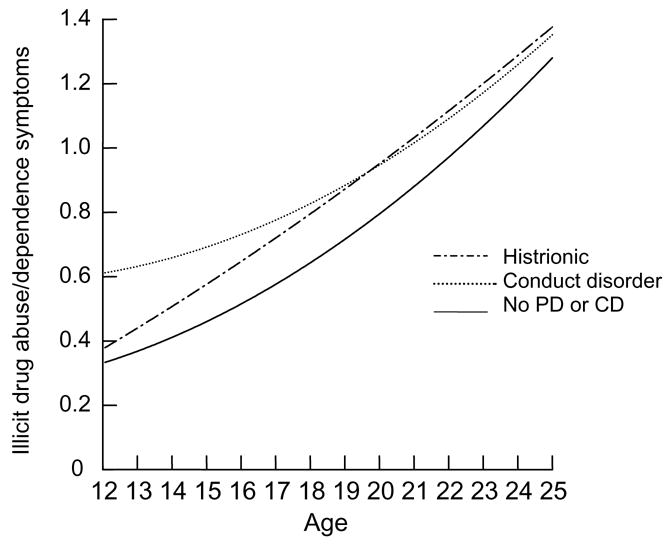

The independent associations of early adolescent PDs and symptoms of illicit drug disorders (other than marijuana) from early adolescence to adulthood are presented in the final model in Table 6 and depicted in Figure 3. When controlling for all other PDs in early adolescence, histrionic PD and conduct disorder were independently associated with higher symptom means across the age range. Conduct disorder was independently associated with a 0.02 unit decrease in the symptoms of illicit drug abuse/dependency per year when comorbid PD effects were taken into account. Thus, those with early adolescent conduct disorder had much elevated early symptoms but subsequent assessments brought their illicit drug-associated symptoms to a level roughly equivalent to that of those with a history of early histrionic PD by age 20 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Trajectories of illicit drug abuse and dependency symptoms by adolescent PD diagnosis

3.8 SUD symptom trajectories between ages 12 and 38 associated with earlier PD and earlier SUD symptom level

The next analyses used multilevel change models to test whether PD and conduct disorder at mean age 13.7 were associated with trajectories of SUD symptom levels over the subsequent 20 years. All analyses included the covariates noted above but in addition current SUD symptoms and age at the 1983 assessment were predictors of subsequent trajectories. Analyses tested whether specific PD diagnoses showed significant effects on alcohol or marijuana use disorder symptom trajectories, including symptoms estimated at age 23 and linear and non-linear changes in symptoms from mean age 16.4 to mean age 33.2. In addition, we investigated the possibility that the influence of early SUD symptoms on the subsequent trajectory may be influenced by comorbidity with PD. These influences may take two hypothesized versions. First, the presence of comorbid PD may increase the risk associated with co-occurring SUD problems with regard to continuity or elevation of such problems over the ensuing years. Second, in the absence of co-occuring SUD symptoms, PD may be an even stronger predictor of higher future SUD symptoms. The rationale for this expectation is that family monitoring may protect many early adolescents from substance use and thus SUD symptoms. At older ages access to these substances is more self-determined and availability increases. Under these circumstances the risk associated with PD may be more readily manifest.

3.9 Alcohol abuse/dependency symptoms

As reported in Table 7, alcohol abuse/dependency symptoms (AAD) in the entire sample increased linearly (about 0.0030 average unit per year combined with a 0.0006 unit deceleration in this increase after age 23 1(the age around which all ages were centered). There was significant and substantial continuity of AAD from this early period (.305 units) as well as significant associations with each of the control variables: higher average symptoms estimated at age 23 for those with parental substance use problems, lower family SES, any Axis I disorder, males, and white respondents. For subsequent models each personality disorder was assessed as a potential predictor of subsequent mean, trajectory, and interaction with current AAD in a model based on the entire sample data and including all covariates.

Table 7.

Personality disorder and alcohol use disorder symptoms from early adolescence to age 38 (N = 600)

| PREDICTORS | ESTIMATED EFFECT (SE) | |

|---|---|---|

| BASIC MODEL | ||

| Intercept | 1.319 (0.023)** | |

| Age at first assessment | 0.005 (0.003) | |

| Linear change with age | 0.003 (0.001)** | |

| Quadratic change with age | −0.0006 (0.0001)** | |

| Alcohol symptoms first assessment (Alc2) | 0.305 (0.028)** | |

| Parental substance use problems | 0.033 (0.016)* | |

| Family SES | 0.030 (0.006)** | |

| Axis I disorder | 0.046 (0.016)** | |

| Sex | 0.083 (0.012)** | |

| Race | 0.050 (0.022)* | |

| ADDED PD | ||

| Paranoid | Effect on mean | − 0.003 (0.033) |

| Effect on linear slope | 0.008 (0.004) * | |

| Interaction with Alc2 | 0.381 (0.090) *** | |

| Schizoid | Effect on mean | − 0.059 (0.045) |

| Effect on linear slope | 0.001 (0.005) | |

| Schizotypal | Effect on mean | 0.038 (0.044) |

| Effect on linear slope | 0.002 (0.005) | |

| Borderline | Effect on mean | 0.019 (0.033) |

| Effect on linear slope | − 0.0005(0.003) | |

| Histrionic | Effect on mean | 0.051 (0.025) * |

| Effect on linear slope | − 0.002 (0.003) | |

| Narcissistic | Effect on mean | − 0.113 (0.040 |

| Effect on linear slope | − 0.007 (−0.004) | |

| Effect on quadratic slope | 0.002 (0.0005)** | |

| Interaction with Alc2 | 0.191 (0.076)** | |

| Avoidant | Effect on mean | 0.062 (0.033) .06 |

| Effect on linear slope | 0.006 (0.004) | |

| Dependent | Effect on mean | − 0.016 (0.030) |

| Effect on linear slope | 0.002 (0.004) | |

| Interaction with Alc2 | − 0.288 (0.127) * | |

| Obsessive-Compulsive | Effect on mean | − 0.039 (0.029) |

| Effect on linear slope | 0.001 (0.004) | |

| Passive-Aggressive | Effect on mean | 0.037 (0.033) |

| Effect on linear slope | 0.001 (0.004) | |

| Interaction with Alc2 | 0.196 (0.082) * | |

| Conduct Disorder | Effect on mean | 0.112 (0.040)** |

| Effect on linear slope | − 0.005 (0.040) | |

Note: All parameter entries are maximum likelihood regression estimates fitted using SAS PROC MIXED and including all covariates. Age was centered by 23.

p < .05;

p < .01.

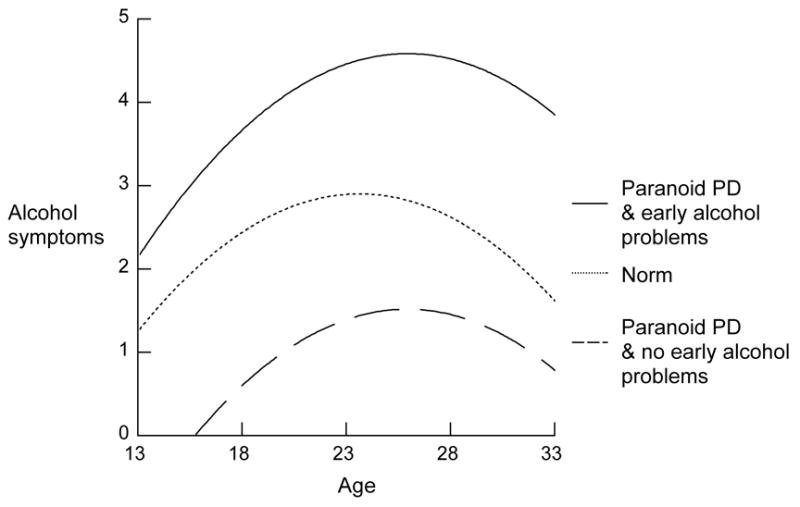

Participants with paranoid PD in early adolescence showed an elevated increase in AAD symptoms per year over the subsequent 20 years: (0.003 + 0.008 = 0.011) as compared to 0.003. In addition, the estimated average symptoms at age 23 was increased from 0.305 in the basic model to 0.305 + 0.381 = 0.686 in those with this disorder (Figure 4). Early schizoid, schizotypal, and borderline PD did not show significant associations with AAD trajectories that were significantly independent of current AAD, nor an influence on the effect of early adolescent AAD. However Histrionic PD was related to higher mean AAD estimated at age 23 and Narcissistic PD was related to lower mean, less decline in AAD after age 23, and a much greater continuity in AAD symptoms from early adolescence on.

Figure 4.

Early alcohol problems and paranoid PD and subsequent trajectory of alcohol symptoms

The positive association of Avoidant PD with mean AAD at age 23 was of marginal statistical significance (p = .06). Dependent PD, on the other hand appears to have a protective effect, with a virtually nil continuity of symptoms from early adolescence (0.305 − 0.288 = 0.017). In contract, passive-aggressive PD, like narcissistic PD was related to a much increased continuity of AAD from early adolescence thereafter. Finally, conduct disorder had a substantial association with subsequent mean ADD symptoms but did not influence either the trajectory or the continuity of early ADD symptoms.

3.10 Marijuana abuse/dependency symptoms

The basic model of the trajectory of marijuana abuse or dependency symptoms (MAD) is provided in Table 8. We see here that the trajectory of MAD in the 20 years following the early adolescent assessment was a strictly linear increase. The effect of early MAD was substantial and symptoms were higher in males and in those with an Axis I disorder other than conduct disorder. There were no significant effects of parental substance use, family SES, or race on MAD symptom means over this period net of earlier MAD.

Table 8.

Personality disorder and marijuana use disorder symptoms from early adolescence to age 38 (N = 600)

| PREDICTORS | ESTIMATED EFFECT (SE) | |

|---|---|---|

| BASIC MODEL | ||

| Intercept | 1.2345 (0.0127)** | |

| Age at first assessment | −0.0019 (0.0014) | |

| Linear change with age | 0.0019) (0.0005)** | |

| Quadratic change with age | −0.00006 (0.00006) | |

| Marijuana symptoms first assessment (Marijuana 2) | 0.2365 (0.0248)** | |

| Parental substance use problems | −0.0025 (0.0084) | |

| Family SES | −0.0015 (0.0035) | |

| Axis I disorder | 0.0366 (0.0090)** | |

| Sex | 0.0306 (0.0064)** | |

| Race | 0.0118 (0.0119) | |

| ADDED PD | ||

| Paranoid | Effect on mean | 0.050 (0.017)** |

| Effect on linear slope | 0.005 (0.002) * | |

| Interaction with Marijuana 2 | −0.184 (0.076) *** | |

| Schizoid | Effect on mean | −0.013 (0.025) |

| Effect on linear slope | 0.002 (0.003) | |

| Schizotypal | Effect on mean | 0.071 (0.021)** |

| Effect on linear slope | 0.003 (0.003) | |

| Interaction with Marijuana 2 | −0.372 (0.059)** | |

| Borderline | Effect on mean | 0.051 (0.016)** |

| Effect on linear slope | −0.004(0.002)* | |

| Interaction with Marijuana 2 | −0.199 (0.052)** | |

| Histrionic | Effect on mean | 0.041 (0.014) ** |

| Effect on linear slope | −0.003 (0.002) | |

| Narcissistic | Effect on mean | 0.007 (0.015) |

| Effect on linear slope | 0.004 (0.002)* | |

| Avoidant | Effect on mean | 0.031 (0.018) .10 |

| Effect on linear slope | 0.0065 (0.0023)** | |

| Dependent | Effect on mean | 0.023 (0.017) |

| Effect on linear slope | −0.003 (0.002) | |

| Interaction with Marijuana 2 | 0.947 (0.272)** | |

| Obsessive-Compulsive | Effect on mean | 0.009 (0.016) |

| Effect on linear slope | 0.002 (0.002) | |

| Interaction with Marijuana 2 | 0.156 (0.070)* | |

| Passive-Aggressive | Effect on mean | 0.050 (0.017)** |

| Effect on linear slope | −0.0001 (0.002) | |

| Interaction with Marijuana 2 | −0.397 (0.053)** | |

| Conduct Disorder | Effect on mean | 0.098 (0.020)** |

| Effect on linear slope | 0.007 (0.002)** | |

| Interaction with Marijuana 2 | − 0.143 (0.056)** | |

Note: All parameter entries are maximum likelihood regression estimates fitted using SAS PROC MIXED and including all covariates. Age was centered by 23.

p < .05;

p < .01.

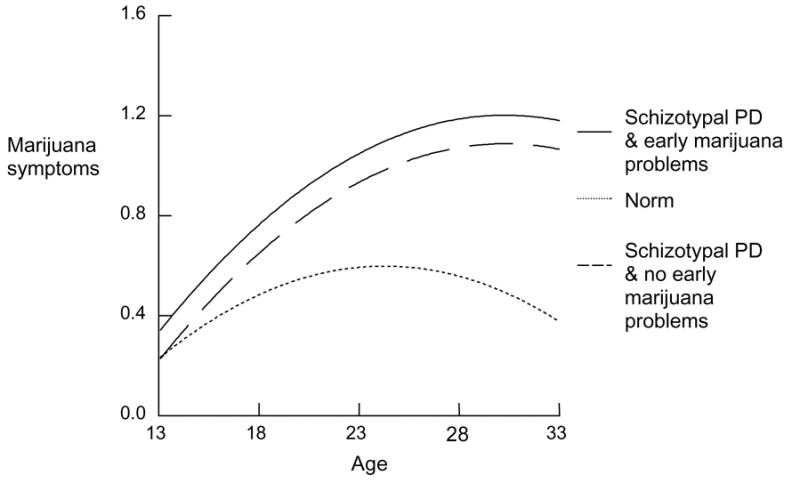

Paranoid PD was independently related to higher subsequent mean MAD symptoms and a steeper trajectory. In addition, among those with no MAD in the early adolescent assessment the impact of paranoid PD on subsequent mean MAD was much greater. Variations on this pattern were also apparent for those with borderline and schizotypal PDs (Figure 5). In the case of schizotypal PD the effect on linear slope was not statistically significant and in the case of borderline PD the effect on linear slope was negative. Nevertheless, in all of these disorders a similar pattern of particular impact on subsequent symptoms in the absence of MAD symptoms in early adolescence is apparent.

Figure 5.

Early marijuana problem and schizotypal PD and subsequent trajectory of marijuana symptoms

The associations of histrionic and narcissistic PD with subsequent MAD are limited to an increase in overall mean for the first and increase in linear trajectory for the second. Avoidant PD was associated with both of these effects. However the other Cluster C PDs, dependent and obsessive compulsive showed higher continuity with early adolescent MAD symptom level or, equivalently, higher impact of these PDs on subsequent elevated MAD mean when early adolescent symptoms were elevated.

4. Discussion

4.1 Overall findings

The present study is the one of the first to document associations between PD and SUDs in a random sample of adolescents from the community. Moreover, this study is the first to examine how early manifestations of PD may influence the developmental course of SUDs from adolescence to adulthood. Because this study controlled for well-known risk factors for SUDs (male gender, conduct disorder, and parental substance abuse), it documents how borderline, histrionic, and narcissistic PDs in early adolescence all represent independent risk factors for the development of SUDs in later adolescence and early adulthood. These Cluster B PDs in adolescence clearly warrant clinical attention when assessing early risks for SUDs and implementing interventions to prevent or treat those disorders.

As expected, PD at mean age 13.7 was associated with increased risk of co-occurring SUD as well as the increase in subsequent onset of marijuana use. Although early adolescent PD-SUD correlation leaves it unclear if PD precedes SUD or vice versa, separate multilevel logistic models indicated that schizotypal, borderline, narcissistic, and passive-aggressive PDs each increased the risk for subsequent substance use diagnoses, as did conduct disorder. In multilevel models, specific PDs also predicted changes in symptom trajectories across from early adolescence to early adulthood. These adolescent PDs were assessed when Axis II disorders are normally at their highest levels (Bernstein et al., 1993; Johnson et al., 2000) and before they begin a normative decline later in adolescence and early adulthood. In contrast, peak rates for the onset of substance abuse generally occur between ages 15 and 19 (Burke, Burke, Regier, & Rae, 1990). As such, the PDs used in our multilevel models showed clear associations with SUDs before, during, and after this peak period of risk for first use of alcohol, marijuana, or other illicit drugs. These analyses indicate PDs may not only predict persistence of some SUD problems over as much as the following two decades but may also represent an elevated risk for onset of SUD problems among adolescents who have not yet begun use.

Consistent with the literature on adults (Trull et al., 2000; Skodol et al., 1999), borderline PD at mean age 13.7 was associated with elevated symptoms of alcohol abuse and marijuana use in adolescence and early adulthood. This effect was observed even after taking conduct disorder, other Axis I and Axis II disorders, male gender, and parental substance abuse into account. Moreover, the observed link between borderline PD and SUDs cannot be attributed to any artifact of overlapping criterion sets in DSM-IV because we did not use any substance abuse items to assess impulsive self-destructive behavior in borderline PD or any other criterion for this Axis II disorder.

There are several ways to explain prospective associations between borderline PD and SUDs. Youths diagnosed with borderline PD in our sample began smoking marijuana at significantly younger ages than those without any PD. Early onset of substance use is noteworthy because it increases the risk for later substance abuse in adolescence and early adulthood (Anthony, & Petronis, 1995; Kandel, Davies, Karus, & Yamaguchi, 1986). Based on the available data presented in Figure 1, borderline PD and histrionic PD also may be associated with earlier onsets for alcohol use symptoms.

Although little is known about shared genetic influences that could link borderline PD and SUDs, it is known that common family risk factors are associated with both forms of disorder. Parental substance abuse is a risk factor for borderline PD and substance abuse in adolescents (Guzder et al., 1999; Johnson, Brent et al., 1995; Widiger & Trull, 1993; Luthar et al, 1993; Merikangas et al., 1998; Miles et al., 1998). Parental substance abuse also may increase risk for sexual abuse that in turn leads to increased risk for substance abuse and borderline PD in adolescents (Brown & Anderson, 1991; Sabo, 1997). Parental substance abuse may also contribute to problematic parenting that has been associated with borderline PD in adolescent offspring (Bezirganian, Cohen, & Brook, 1993). It thus could be that various environmental risk factors for borderline PD are indirectly influenced by genetic risks that are well-documented for substance abuse (e.g., Tsuang et al., 1996).

Figures 1 and 2 suggest that alcohol and marijuana symptoms around age 12 are comparably elevated for participants diagnosed with conduct disorder and borderline PD. Both disorders are characterized by impulse control problems that may increase susceptibility to substance abuse problems, perhaps especially in early adolescence. However, borderline PD is also characterized by marked affect dysregulation that is not a part of the conduct disorder syndrome. Substance abuse associated with borderline PD thus may reflect a maladaptive self-medicating strategy intended to regulate dysphoric affect (Casillas & Clark, 2002; Dulit, Fyer, Haas, Sullivan, & Frances, 1990). Substance abuse co-occurring with conduct disorder and antisocial PD, in contrast, may reflect novelty-seeking behavior that is genetically mediated (Heath, Cloninger, & Martin, 1994; Howard, Kivlahan, & Walker, 1997).

Conduct disorder almost invariably had the largest effect size as a predictor of substance abuse in models that simultaneously included PDs, age, sex, and other co-occurring Axis I disorders. Whereas the long-term trajectory for alcohol and marijuana abuse associated with borderline PD in early adolescence gradually decelerated and intersected with more normative levels around age 23, trajectories associated with conduct disorder remained at higher levels throughout adolescence and early adulthood. On average, youths with conduct disorder also appear to start smoking marijuana at a much younger age (13.6 years) than those diagnosed with borderline PD (16.5 years). Based on differences in onset, trajectory, and overall severity, borderline PD and conduct disorder each appear to have unique profiles as risk factors for SUDs.

Histrionic and narcissistic PDs also reflect elevated risk for alcohol abuse independent of risks associated with borderline PD and conduct disorder. Histrionic PD is also associated with increased risk for illicit drug use. These findings replicate findings elsewhere (Grilo et al., 1995; Skodol et al., 1999) suggesting that Cluster B PDs are more consistently associated with SUDs than Cluster A PDs (paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal PDs) or from Cluster C PDs (avoidant, dependent, obsessive-compulsive PDs). When analyzed here as separate predictor variables, avoidant and schizotypal PDs initially appeared to be associated with subsequent SUDs. However, the effects of these Clusters A and C PDs lost significance when Cluster B PDs were simultaneously included in the model. Young people with schizotypal or avoidant PD may thus be at probable risk for SUDs based on how much they also present with borderline PD or other Cluster B disorders. In our sample seven of the 26 participants (27%) diagnosed with avoidant PD also had borderline PD, and eight of 19 participants (42%) diagnosed with schizotypal PD also had borderline PD, thereby illustrating how borderline PD frequently co-occurs with PDs from different diagnostic clusters.

People diagnosed with passive-aggressive PD, in contrast, remained significantly associated with alcohol and marijuana abuse/dependence disorders even after taking into account other PDs, conduct disorder, and all other control variables used in this study. Passive-aggressive traits, however, are observed so frequently together with other PDs that the utility of passive aggressive PD as a distinct diagnostic construct has been questioned. In this context our finding that passive-aggressive traits play a prominent role in SUDs suggests a strong effect regardless of what other PD or conduct disorder symptoms might also be present.

Can we say that personality disorder in early adolescence has an unambiguous causal impact on the probability of SUD or the level of SUD symptoms? Some PDs are certainly risk indicators for subsequent initiation, onset, or higher level symptoms of these problems. Nevertheless, as is likely the case for psychiatric disorders more generally, comorbidity may often develop out of shared biological and environmental risks. For any given pair of disorders, including substance use disorders, once either or both develops, the consequences of each may then constitute a risk for further increase or persistence of the other. When there are age-regulated disorder exposures, such as substance access, the timing of these problems will further modulate the reciprocal influences that may ensue. Thus, at least some PDs may be indicators of more basic risk for SUD without actually mediating the effect of these basic risks, despite the relationships with future onset or elevated symptoms of SUD. That is, the comorbidity reflects common causes, and the ability to express PD at a younger age than one can access problematic substances may be the source of the apparent sequence effect often attributed to causation.

4.2 Clinical Implications

When borderline PD and SUDs occur in combination, they are known to increase risk for suicidal behavior in adult patients in treatment for SUDs or Axis II disturbances (O’Boyle & Brandon, 1998; Yen et al., 2003). Other research has documented how borderline PD increases risk of violence victimization or perpetration in a sample of perinatal substance abusers (Haller & Miles, 2003). Furthermore, co-occurring Axis II and SUDs are associated with significantly worse compliance with follow-up treatment after inpatient hospitalizations (Links, et al., 1995; Ross, et al., 2003). Serious risks associated with co-occurring PD and SUD are thus well known in clinical settings for adults but they are only beginning to be documented in adolescents. The present results strongly suggest that clinicians should evaluate their patients for the presence of PDs, especially Cluster B PDs, when assessing or treating SUDs in adolescents.

Treatments are emerging to assist patients presenting with co-occurring PD and SUD. Although originally designed to treat borderline PD, Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT; Linehan, 1993) has been adapted and evaluated for treatment of SUD (Dimeff, Rizvi, Brown, & Linehan, 2000) and SUD that co-occurs with borderline PD (van den Bosch, Verheul, Schippers, & van den Brink, 2002). Skills training interventions used in DBT have also been integrated with family therapy for adolescent patients with SUDs (Santisteban, Muir, Mena, & Mitrani, 2003).

4.3 Strengths and Limitations

Because this study assessed PDs and SUDs in a randomly selected community sample, its estimates of co-occurring psychiatric disorders are not artificially inflated by ascertainment bias. Prospective assessment of psychiatric disorders ensured that our findings were not distorted by error accompanying retrospective reports of adolescent disturbances by adult respondents. Although this study relies on measures of PD that are unique to our sample, the findings reported here are largely consistent with the available literature on co-occurring PDs and SUDs in adults and adolescents. Furthermore, our study employs rigorous controls for co-occurring psychiatric disorders and other risk factors that otherwise might account for the associations we found between Cluster B PDs in early adolescence and subsequent SUDs. Although this study indicates that PDs represent long-term risks for SUDs that are independent of conduct disorder, additional research is needed to clarify which risk aspects are unique to PDs and thereby distinguish them from risks associated with conduct disorder.

As for any study of SUD in young people, findings are likely to be somewhat conditional on the cohort being investigated, secular changes in usage patterns of psychoactive drugs being so common in young people. Nevertheless, we look to our research for findings that will generalize beyond the given research cohort. For this reason, the 10 birth-year span of this cohort is slightly advantageous in comparison to a cohort born in a single year. This cohort was born between 1965 and 1975 and thus “turned 15” across the decade of the 1980’s. On the other hand, the findings must be averaged over this cohort span, and may thus be less easily compared to other cohort studies. Another limitation is the modest sample size, especially for the investigation of the stronger illicit drugs. Our self-reported data produced very few cases meeting diagnostic criteria for these drugs, and thus extreme symptom distributions requiring statistical transforms to roughly meet the criteria for the statistical analyses we carried out. Thus these analyses should be considered tentative until supported by other studies.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant MH-36971, MH-38916, MH-49191, DA-03188, and DA016977-01.

Footnotes

Because of the transformation of the symptom measures required to improve the variable distribution conformity with the assumptions of the statistical model, the scale cannot be directly interpreted as number of symptoms. In addition the measure of early adolescent AAD was centered by subtracting its mean in order to facilitate interpretation of interaction effects.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony JC, Petronis KR. Early-onset drug use and risk of later drug problems. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1995;40:9–15. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01194-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball SA, Tennen H, Poling JC, Kranzler HR, Rounsaville BJ. Personality, temperament, and character dimensions and the DSM-IV personality disorders in substance abuse. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:545–553. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkson J. Limitations of the application of fourfold table analysis to hospital data. Biometrics. 1946;2:47–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Cohen P, Velez CN, Schwab-Stone M, Siever LJ, Shinsato L. Prevalence and stability of the DSM-III-R personality disorders in a community-based survey of adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150:1237–1243. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.8.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein D, Cohen P, Skodol A, Bezirganian S, Brook J. Childhood antecedents of adolescent personality disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;153:907–913. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.7.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezirganian S, Cohen P, Brook JS. The impact of mother-child interaction on the development of borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150:1836–1842. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.12.1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird HR, Gould M, Staghezza B. Aggregating data from multiple informants in child psychiatry epidemiological research. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1992;49:282–291. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199201000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle MH, Offord DR, Racine YA, Szatmari P, Gleming JE, Links PS. Predicting substance use in late adolescence: results from the Ontario Child Health Study followup. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;149:761–767. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.6.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GR, Anderson B. Psychiatric morbidity in adult inpatients with childhood histories of sexual and physical abuse. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;148:55–61. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke KC, Burke JD, Regier DA, Rae DS. Age at onset of selected mental disorders in five community populations. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1990;47:511–518. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810180011002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casillas A, Clark LA. Dependency, impulsivity, and self-harm: Traits hypothesized to underlie the association between cluster B personality and substance use disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2002;16:424–436. doi: 10.1521/pedi.16.5.424.22124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Chen H, Hamigami F, Gordon K, McArdle JJ. Multilevel analyses for predicting sequence effects of financial and employment problems on the probability of arrest. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2000;16:223–235. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Cohen J. Adolescent life values and mental health. Mahwah NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Edelbrock CS, Duncan MK, Kalas R. Final Report to the Center for Epidemiological Studies, NIMH. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh; 1984. Testing of the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC) in a Clinical Population. [Google Scholar]

- DeJong CAJ, van den Brink W, Harteveld FM, van der Wielen GM. Personality disorders in alcoholics and drug abusers. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1993;34:87–94. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(93)90052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff L, Rizvi SL, Brown M, Linehan MM. Dialectical behavior therapy for substance abuse: A pilot application to methamphetamine-dependent women with borderline personality disorder. Cognitive & Behavioral Practice. 2000;7:457–468. [Google Scholar]

- Driessen M, Veltrup C, Wetterling T, John U, Dilling H. Axis I and Axis II comorbidity in alcohol dependence and the two types of alcoholism. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1998;22:77–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulit RA, Fyer MR, Haas GL, Sullivan T, Frances AJ. Substance use in borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;147:1002–1007. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.8.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulit RA, Fyer MR, Miller FT, Sacks MH, Frances AJ. Gender differences in sexual preference and substance abuse of inpatients with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1993;7:182–185. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Benjamin LS. User’s guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM IV Personality Disorders. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gittelman R, Manuzza S, Shenker R, Bonagura N. Hyperactive boys almost grown up. I: Psychiatric status. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1985;42:937–947. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790330017002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Becker DF, Walker ML, Levy KN, Edell WS, McGlashan TH. Psychiatric comorbidity in adolescent inpatients with substance use disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:1085–1091. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199508000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Martino S, Walker ML, Becker DF, Edell WS, McGlashan TH. Controlled study of psychiatric comorbidity in psychiatrically hospitalized young adults with substance use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:1305–1307. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.9.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Walker ML, Becker DE, Edell WS, McGlashan TH. Personality disorders in adolescents with major depression, substance abuse disorders, and coexisting major depression and substance use disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:328–332. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.2.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzder J, Paris J, Zelkowitz P, Feldman R. Psychological risk factors for borderline pathology in school-age children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:206–212. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199902000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haller DL, Miles DR. Victimization and perpetration among perinatal substance abusers. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2003;18:760–780. doi: 10.1177/0886260503253239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath AC, Cloninger CR, Martin NG. Testing a model for the genetic structure of personality: A comparison of the personality systems of Cloninger and Eysenck. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;66(4):762–775. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.66.4.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesslebrock MN. Childhood behavior problems and adult antisocial personality disorder in alcoholism. In: Meyer RE, editor. Psychopathology and addictive disorders. New York: Guilford; 1986. pp. 78–94. [Google Scholar]

- Howard MO, Kivlahan D, Walker RD. Cloninger’s tridimensional theory of personality and psychopathology: Applications to substance use disorders. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58(1):48–66. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyler SE, Rieder R, Spitzer R, Williams J. The Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire (PDQ) New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Hyler SE, Rieder RO, Williams JBW, Spitzer RL, Hendler J, Lyons M. The Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire: Development and preliminary results. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1988;(2):229–237. [Google Scholar]

- Jang KL, Vernon PA, Livesley WJ. Personality disorder traits, family environment, and alcohol misuse: A multivariate behavioural genetic analysis. Addiction. 2000;95:873–888. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9568735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BA, Brent DA, Connolly J, Bridge J, Matta J, Constantine D, Rather C, White T. Familial aggregation of adolescent personality disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:798–804. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199506000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Kasen S, Skodol A, Brook J. Age-related change in personality disorder trait levels between early adolescence and adulthood: a community-based longitudinal investigation. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2000;102:265–275. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102004265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Skodol AE, Oldham JM, Kasen S, Brook JS. Personality disorders in adolescence and risk of major mental disorders and suicidality during adulthood. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:805–811. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.9.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Hyler SE, Skoldol AE, Bornstein RF, Sherman M. Personality disorder symptomatology associated with adolescent depression and substance abuse. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1995;9:318–329. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Williams JBW, Goetz RR, Rabkin JG, Remien RH, Lipsitz JD, Gorman JM. Personality disorders predict onset of Axis I disorders and impaired functioning among homosexual men with and at risk for HIV infection. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:350–357. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830040086013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Davies M, Karus D, Yamaguchi K. The consequences in young adulthood of adolescent drug involvement: An overview. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1986;43:746–754. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800080032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Kessler RC, Margulies RZ. Antecedents of adolescent initiation into stages of drug use: A developmental analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1978;7:13–40. doi: 10.1007/BF01538684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasen S, Cohen P, Skodol A, Johnson JG, Brook JS. The influence of childhood psychiatric disorders on more persistent forms of psychopathology in young adulthood. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156 (10):1529–1535. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.10.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan LS, Smith J, Jenkins S. Ecological validity of indicator data as predictors of survey findings. Journal of Social Service Research. 1977;1:117–132. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. NY: Guiford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Links PS, Heslegrave RJ, Mitton JE, Van Reekum R, et al. Borderline personality disorder and substance abuse: Consequences of comorbidity. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;40:9–14. doi: 10.1177/070674379504000105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlel RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD. SAS System for Mixed Models. Cary, N.C.: SAS Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Merikangas KR, Rounsaville BJ. Parental psychopathology and disorders in offspring: A study of relatives of drug abusers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disorders. 1993;181:351–357. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199306000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Stolar M, Stevens DE, Goulet J, Preisig MA, Fenton B, Zhang H, O’Malley SS, Rounsaville BJ. Familial transmission of substance use disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:973–979. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.11.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles DR, Stallings MC, Young SE, Hewitt JK, Crowley TJ, Fulker DW. A family history and direct interview study of familial aggregation of substance abuse: The adolescent substance abuse study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1998;49:105–114. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Langenbucher J, Labouvie E, Miller KJ. The comorbidity of alcoholism and personality disorders in a clinical population: Prevalence rates and relation to alcohol typology variables. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:74–84. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nace EP, Davis CW, Gaspari JP. Axis II comorbidity in substance abusers. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;148:118–120. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Boyle M. Personality disorder and multiple substance dependence. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1993;7:342–347. [Google Scholar]

- O’Boyle M, Brandon EAA. Suicide attempts, substance abuse, and personality. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1998;15:353–356. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00224-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, Goodwin FK. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1990;264:2511–2518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey JM, Morris-Yates A, Singh M, Andrews G, Stewart GW. Continuities between psychiatric disorders in adolescents and personality disorders in adults. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;52:895–900. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.6.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey JM, Singh M, Morris-Yates A, Andrews G. Referred adolescents as young adults: The relationship between psychosocial functioning and personality disorder. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;31:219–226. doi: 10.3109/00048679709073824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN. Deviant children grown up: A social and psychiatric study of sociopathic personality. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Price RK. Adult disorders predicted by childhood conduct problems: results from the NIMH Epidemiologic Catchment Area Project. Psychiatry. 1991;54:116–132. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1991.11024540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross S, Dermatis H, Levounis P, Galanter M. A comparison between dually diagnosed inpatients with and without Axis II comorbidity and the relationship to treatment outcome. American Journal of Drug & Alcohol Abuse. 2003;29:263–279. doi: 10.1081/ada-120020511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Kranzler HR, Ball S, Tennen H, Poling J, Triffleman E. Personality disorders in substance abusers: Relation to substance use. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1998;186:87–95. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199802000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabo AN. Etiological significance of associations between childhood trauma and borderline personality disorder: Conceptual and clinical implications. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1997;11:50–70. doi: 10.1521/pedi.1997.11.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban DA, Muir JA, Mena MP, Mitrani VB. Integrative borderline adolescent family therapy: Meeting the challenges of treating adolescents with borderline personality disorder. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2003;40(4):251–264. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.40.4.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skodol AE, Oldham JM, Gallaher PE. Axis II comorbidity of substance use disorders among patients referred for treatment of personality disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:733–738. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.5.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Sher KJ, Minks-Brown C, Durbin J, Burr R. Borderline personality disorder and substance use disorders: A review and integration. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;2:235–253. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]