SYNOPSIS

Gastrointestinal eosinophilia, as a broad term for abnormal eosinophil accumulation in the GI tract, involves many different disease identities. These diseases include primary eosinophil associated gastrointestinal diseases, gastrointestinal eosinophilia in HES and all gastrointestinal eosinophilic states associated with known causes. Each of these diseases has its unique features but there is no absolute boundary between them. All three groups of GI eosinophila are described in this chapter although the focus is on primary gastrointestinal eosinophilia, i.e. EGID.

Keywords: Eosinophil, gastrointestinal, inflammation, pathogenesis, therapy

INTRODUCTION

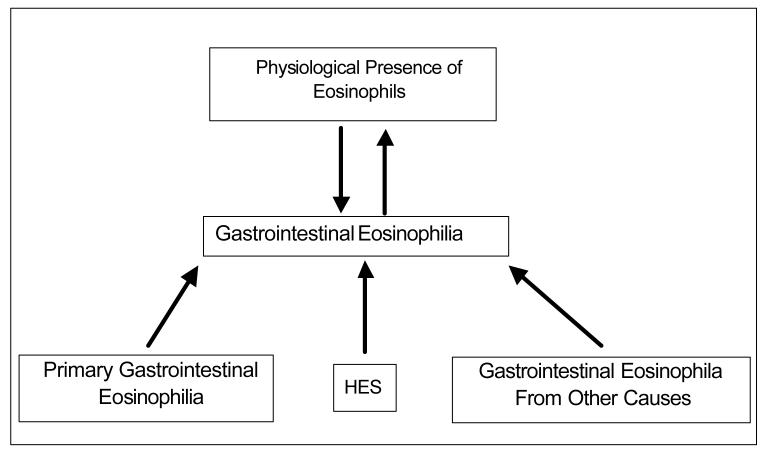

The presence of eosinophils in tissues and blood is a physiological phenomenon. Eosinophils have roles in both host defense and pathological processes even though we are still not certain about their overall function. A unique feature of eosinophils is that they largely reside in the tissues, instead of staying in the blood circulation like neutrophils do. In fact, the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is a primary site for normal eosinophil residence. Significant progress has been made in elucidating that eosinophils are integral members of the GI mucosal immune system. In physiological states, small numbers of eosinophils are found throughout the GI tract except esophagus. Gastrointestinal eosinophilia is a broad term for any abnormal eosinophil accumulation in the GI system induced in diverse states. In this chapter, we will group GI eosinophilia into three categories: First, primary GI eosinophilia, also termed eosinophil associated gastrointestinal disorders (EGID). These diseases selectively affect the gastrointestinal tract with eosinophil-rich inflammation in the absence of known causes for eosinophilia. These disorders include eosinophilic esophagitis (EE), eosinophilic gastritis, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, eosinophilic enteritis, and eosinophilic colitis, and are being increasingly recognized; second, GI eosinophilia resulting from hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES); and third, GI eosinophilia triggered by other known causes of eosinophilia, such as drug reactions, parasitic infections, malignancy, etc. All three groups of GI eosinophila will be described in this chapter although the focus will be on primary gastrointestinal eosinophilia, i.e. EGID. ( Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Gastrointestinal Eosinophilia

PHYSIOLOGICAL PRESENCE OF EOSINOPHILS IN THE GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT

Even though eosinophils have been noted to be present at low levels in numerous tissues as well as in the blood circulation, when a large series of biopsy and autopsy specimens were analyzed, the only organs that demonstrated tissue eosinophils (at substantial levels) were the GI tract, spleen, lymph nodes, and thymus.[1] Notably, eosinophil infiltrations were only associated with eosinophil degranulation in the GI tract. Examination of eosinophils throughout the GI tract of conventional healthy mice (untreated mice maintained under pathogen-free conditions) has revealed that eosinophils are normally present in the lamina propria of the stomach, small intestine, cecum, and colon.[2] Notably, unlike intestinal lymphocytes and mast cells, eosinophils are not normally present in Peyer's patches or intra-epithelial locations, although they commonly infiltrate these regions in primary GI eosinophilia.[3] Data have suggested that eosinophils respond to distinct stimuli compared with other intestinal leukocytes;[2] constitutive expression of eotaxin-1 has also been demonstrated to provide the unique signal that promotes localization of eosinophils into the GI tract at baseline. A recent study has shown that tissue-dwelling eosinophils have distinct cytokine expression patterns under inflammatory or non-inflammatory conditions, with esophageal eosinophils from eosinophilic esophagitis patients expressing relatively high levels of Th2 cytokines.[4]

FUNCTION OF EOSINOPHILIA IN THE GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM

Despite the significant progress in histological studies of GI eosinophilia, the function of eosinophils in Gl tract is still not well understood. In general, eosinophils play both protective and pathological roles in the GI tract. As part of their protective role, eosinophils are involved in host response against parasitic infections. As part of their involvement in eliciting tissue pathology, allergen-triggered Th2 responses, mediated by IL-5 and IL-13 (for example) have been shown to elicit esophageal pathology, at least in the setting of experimental models in mice. These pathological changes can induce fixed structural lesions such as stricture. In vitro studies have shown that eosinophil granule constituents are toxic to a variety of tissues including intestinal epithelium.[5] Eosinophil granules contain a crystalloid core composed of major basic protein (MBP)-1 (and MBP-2), and a matrix composed of eosinophil cationic protein (ECP), eosinophil-derived neurotoxin (EDN), and eosinophil peroxidase (EPO).[6] These cationic proteins share certain pro-inflammatory properties but differ in other ways. For example, MBP, EPO, and ECP have cytotoxic effects on epithelium, in concentrations similar to those found in biological fluids from patients with eosinophilia. Additionally, ECP and EDN belong to the Ribonuclease A superfamily and possess anti-viral and ribonuclease activity. [7,8] ECP can insert voltage insensitive, ion-nonselective toxic pores into the membranes of target cells and these pores may facilitate the entry of other toxic molecules.[9] MBP directly increases smooth muscle reactivity by causing dysfunction of vagal muscarinic M2 receptors.[10] MBP also triggers degranulation of mast cells and basophils. Triggering of eosinophils by engagement of receptors for cytokines, immunoglobulins, and complement can lead to the generation of a wide range of inflammatory cytokines including IL-1, -3, -4, -5, -13, GM-CSF, transforming growth factors, TNF-α, RANTES, MIP-1α, vascular endothelial cell growth factor, and eotaxin-1, indicating that they have the potential to modulate multiple aspects of the immune response.[11] In fact, eosinophil-derived transforming growth factor-β is linked with epithelial growth, fibrosis, and tissue remodeling.[12,13] Eosinophils express MHC class-II molecules, relevant co-stimulatory molecules (CD40, CD28, B7.1 and B7.2) and secrete an array of cytokines capable of promoting lymphocyte proliferation, activation and Th1 or Th2 polarization (IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-12, IL-10). [11,14-17] Further eosinophil-mediated damage is caused by toxic hydrogen peroxide and halide acids generated by EPO and by superoxide generated by the respiratory burst oxidase enzyme pathway in eosinophils. Eosinophils also generate large amounts of the LTC4, which is metabolized to LTD4 and LTE4. These three lipid mediators increase vascular permeability and mucus secretion, and are potent stimulators of smooth muscle contraction.[18] Clinical investigations have demonstrated extracellular deposition of MBP and ECP in the small bowel of patients with eosinophilic gastroenteritis and have shown a correlation between the level of eosinophils and disease severity. Electron microscopy studies have revealed ultrastructural changes in the secondary granules (indicative of eosinophil degranulation and mediator release) in duodenal samples from patients with eosinophilic gastroenteritis.[19] Furthermore, Charcot-Leyden crystals, remnants of eosinophil degranulation, are commonly found on microscopic examination of stools obtained from patients with eosinophilic gastroenteritis.[20,21]

Evidence has also supported the association between eosinophils and the enteric nervous system, contributing to the pathogenesis of disease. A recent human study showed the close association of mucosal eosinophils and their granule proteins with the myenteric ganglia. In vitro study also showed the effect of eosinophils on the activation of nerves as well as on nerve remodeling, including the increase of adhesion molecules, muscarinic M2 receptors and nerve growth factor production. Therefore it is possible that the eosinophil-enteric nerve interaction contribute to the intestinal dysmotility that occurs in EGID.

PRIMARY GASTROINTESTINAL EOSINOPHILIA

Patients with EGID suffer from a variety of problems including failure to thrive, abdominal pain, irritability, gastric dysmotility, vomiting, diarrhea, and dysphagia. [22,23] Even though the term “primary” is used here, evidence is accumulating supporting the concept that EGID arises secondary to the interplay of genetic and environmental factors. Notably, a large percentage (∼10%) of patients suffering from EGID have an immediate family member with EGID.[22] Additionally, several lines of evidence support an allergic etiology including the finding that ∼75% of patients with EGID are atopic, [21,24-30] that the severity of disease can sometimes be reversed by institution of an allergen-free diet,[29-31] and the common finding of mast cell degranulation in tissue specimens.[32,33] Importantly, our recent models of EGID support a potential allergic etiology for these disorders.[34] Interestingly, despite the common finding of food-specific IgE in patients with EGID, food-induced anaphylactic responses occur in only a minority of patients.[19,35] Thus, EGID have properties that fall between pure IgE-mediated food allergy and cellular-mediated hypersensitivity disorders (e.g. Celiac disease). [35]

Although the incidence of primary EGID has not been rigorously calculated, a mini-epidemic of these diseases (especially EE) has been noted over the last decade. [36][37] For example, EE is a global health disease now reported in Australia,[38] Brazil,[39] England,[40] Italy,[41] Japan,[42] Spain[43][44] and Switzerland.[45] Liacouras and his group at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia have found that ∼10% of their pediatric patients with GERD-like symptoms who are unresponsive to acid blockade have EE.[46][47] Furuta and his colleagues at Boston Children's Hospital have reported that 6% of their patients with esophagitis have EE.[48] Over a 16-year observation period, Straumann and his colleagues have documented a prevalence of ∼1:4000 adults in Switzerland.[4] Croese and colleagues have reported EE to be present in 1:70,000 adults in an Australian provincial city.[39] Finally, we have noted that EE occurs in 1:2,000 children in the Cincinnati metropolitan area over a 5 year time period[49] (and unpublished findings). Collectively, these epidemiological results indicate that EGID is not an uncommon group of diseases, and may have a combined prevalence even higher than pediatric IBD.

Evaluation for EGID

Patients with EGID present with a variety of clinical problems, most commonly failure to thrive, abdominal pain, irritability, gastric dysmotility, vomiting, diarrhea, dysphagia, microcytic anemia, and hypoproteinemia. [22] A diagnostic evaluation for EGID should be performed on all patients with these refractory problems, especially in individuals with a strong history of allergic diseases, peripheral blood eosinophilia, and/or a family history of EGID. Depending upon the intestinal segment involved, the frequency of specific symptoms varies (e.g. abdominal pain and dysphagia are most common in eosinophilic gastroenteritis and EE, respectively), but there are no pathognomonic symptoms or blood tests for diagnosing EGID. Notably, blood eosinophil counts are normal in the majority of patients. If EGID is suspected (based on clinical presentation or evaluation of endoscopic biopsies), then additional testing should be considered to rule out the possibility that there may be another primary disease process such as drug hypersensitivity, collagen-vascular disease, malignancy, or infection.

The evaluation for EGID starts with a comprehensive history and physical examination. Evaluation for intestinal parasites by examination of stool samples, intestinal aspirates obtained during colonoscopy, or specific blood antibody titres should be performed, especially when patients have high-risk exposure (e.g. living on farms or drinking well water). For example, in one series of patients with eosinophilic enteritis, the common dog hookworm Ancylostoma caninum (identified by endoscopic detection) has been shown to be the cause of eosinophilic enteritis in 15% of patients,[50] raising the possibility that other occult infections may be involved in the pathogenesis of other apparent cases of EGID. As a precaution, before using systemic immunosuppression for EGID, infection with Strongyloides stercoralis should ruled out, since this infection can become life-threatening in the setting of systemic immunosuppression.[51] The evaluation of total IgE levels has significance in stratifying patients with atopic variants of EGID or suggesting further consideration for occult parasitic infections. Notably, skin prick testing to a panel of food and aeroallergens helps to identify sensitizations to specific allergens. Indeed, patients with the atopic variant of EGID have evidence of IgE sensitization to a mean of 14 different food groups.[22] A preliminary study has suggested a value for delayed cutaneous hypersensitivity testing (skin patch testing) for specific food antigens, in further identifying allergic variants of EE.[30]

The diagnosis of EGID is dependent upon the microscopic evaluation of endoscopic biopsy samples, with careful attention to the quantity, location, and characteristics of the eosinophilic inflammation. Patients with EGID often present with a clear history and positive biopsy results for the disease but have a variety of endoscopic findings.[52] It is not uncommon for endoscopic appearances of the gastrointestinal tract to look normal; thus, microscopic evaluation of biopsy samples is essential. Furthermore, the disease often has patchy involvement, necessitating the analysis of multiple endoscopic biopsies from each intestinal segment.[53] Because no widely accepted diagnostic criteria has been established for EGID, the diagnosis is dependent upon the expertise of the physicians involved in the evaluation of the biopsy samples. While the normal esophagus is devoid of eosinophils, the rest of the gastrointestinal tract contains readily detectable eosinophils.[54] Thus, differentiation of EGID from the normal condition relies on several factors including (1) eosinophil quantification (and comparisons to normal values at each medical center); (2) the location of eosinophils (e.g. their presence in abnormal positions such as the intra-epithelial and intestinal crypt regions); (3) associated pathological abnormalities (e.g. epithelial hyperplasia as in the case of EE), and (4) the absence of pathological features suggestive of other primary disorders (e.g. neutrophilia associated with IBD, or vasculitis associated with Churg-Strauss syndrome). Based on these criteria, patients often suffer from symptoms for an extended period of time (mean of 4 years) before a bona fide diagnosis of EGID is established.[22]

Eosinophilic Esophagitis

Among all primary gastrointestinal eosinophilic diseases, EE is unique due to the fact that the esophagus in a healthy individual is completely devoid of eosinophils, not like other parts of GI tract.[55] Therefore, any eosinophils in the esophagus may indicate a disease process. In general, esophageal eosinophil numbers in EE are much higher than in GERD. The diagnosis of EE is usually defined as a positive esophageal biopsy showing more than 15 eosinophils/HPF. In most cases, esophageal eosinophil numbers in GERD is under 7 and the concurrence of GERD and allergy may have 7-20 eosinophils/HPF. However, a recent study by Ngo et al. reported three GERD patients with esophageal eosinophil numbers between 21-52/HPF who were successfully treated with a proton pump inhibitor.[56] The key difference between EE and GERD is not the absolute numbers of eosinophils in the esophagus. Instead, EE patients will have persistent esophageal eosinophilia even with proton pump inhibitor treatment.

Treatment of EGID

Principles of treatment for EE, eosinophilic gastroenteritis and colitis are similar. Eliminating the dietary intake of the foods implicated by skin prick testing (or RAST testing) has variable effects, but complete resolution is generally achieved with an amino acid-based elemental diet.[57] Once disease remission has been obtained by dietary modification, the specific food groups are slowly reintroduced (at ∼3 week intervals for each food group) and endoscopy is performed every 3 months, to identify sustained remission or disease flare-up. Drugs such as cromoglycate, montelukast, ketotifen, suplatast tosilate, mycophenolate mofetil (a inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase inhibitor), and “alternative Chinese medicines” have been advocated,[22,23] but are generally not successful in the author's experience. In our institution, an appropriate therapeutic approach includes a trial of food elimination if sensitization is found by food skin testing and/or RAST. If no sensitization is found or if specific food avoidance is not feasible, an elemental formula is instituted. Up to now, the management of EGIDs, besides elemental diet as mentioned above, includes four parts: systemic and topical steroids, non-corticosteroid therapy, management of other EGID complications (such as iron deficiency and anemia) and the management of therapeutic toxicity.[59] Anti-inflammatory drugs (systemic or topical steroids) are the main therapy in cases where diet restriction is not feasible or has failed to improve the disease. For systemic steroid therapy, a course of 2 to 6 weeks of therapy with relatively low doses seems to work better than a 7-day course of burst glucocorticoids. There are several forms of topical glucocorticoids designed to deliver drugs to specific segments of the gastrointestinal tract (e.g. budesonide tablets [Entocort™ EC] designed to deliver drug to the ileum and proximal colon). As with asthmatic treatment, topical steroids have a better benefit-to-risk effect compared to systemic steroids. Currently, anti-IL-5 and anti-IgE trials are in progress and some studies have shown promising results.[60] In severe cases refractory or dependent upon glucocorticoid therapy, intravenous alimentation or immunosuppressive antimetabolite therapy (azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine) are alternatives. Finally, even if GERD is not present, neutralization of gastric acidity (with proton pump inhibitors) may improve symptoms and the degree of esophageal and gastric pathology.

GASTROINTESTINAL EOSINOPHILIA IN HYPEREOSINOPHILIC SYNDROME (HES)

The term HES, was introduced by Anderson and Hardy in 1968 to designate patients with marked eosinophilia in the absence of other causes of eosinophilia.[61] They reported three patients, all males, between the ages of 34 to 47 who suffered from cardiopulmonary symptoms, fever, sweats, weight loss and marked eosinophilia. Two of the patients died, and at autopsy, their hearts were enlarged and showed mural thrombi. Multiple organs are involved in HES, including heart, lung, skin, nervous system, and GI system. Due to the involvement of the GI system, HES may be confused with EGID. However, HES usually involves many other organs with heart, skin, and CNS as its major target organs. The treatment for HES is similar to those utilized for patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia, including prednisone, hydroxyurea, and interferon-α. Chusid and his associates formulated the diagnostic criteria for HES to include (1) persistent eosinophilia of at least 1500 cells/mm2 for a minimum of six months; (2) lack of known causes for eosinophilia (e.g parasitic or allergic triggers); and (3) symptoms and signs of organ system involvement.[62] Based on these diagnostic criteria, patients with EGID and blood eosinophil counts >1500/mm2 meet the diagnostic criteria. However, patients with EGID generally do not have the high risk of life-threatening complications associated with classic HES (i.e. the cardiomyopathy, or central nervous system involvement). Notably, considerable heterogeneity among HES patients has been recognized. For example, T cell clones producing the characteristic Th2 cytokines, IL-4 and IL-5, have been found in patients satisfying the diagnostic criteria for HES.[63,64] However, perhaps the most striking advance in our understanding of HES has resulted from treatment of HES patients with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor, imatinib mesylate.[65-69] Imatinib was introduced for the treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia and has had a remarkable effect in that disease. Treatment of many HES patients with imatinib mesylate causes a dramatic reduction of peripheral blood and bone marrow eosinophils suggesting that certain HES patients express a novel kinase sensitive to imatinib mesylate. Further investigation of the ability of imatinib mesylate to treat HES patients revealed the existence of an 800 kilobase deletion in chromosome 4 bringing together an upstream DNA sequence homologous to a yeast protein, referred to as FIP1, and designated as like FIP1, or FIP1-L1 and the gene for the cytoplasmic domain of the platelet derived growth factor alpha (PDGFRA) receptor.[65,70] This fusion gene is transcribed and translated yielding a novel kinase referred to as FIP-L1-PDGFRA; FIP-L1-PDGFRA is exquisitely sensitive to imatinib in vitro, thus explaining the remarkable sensitivity of HES patients to this drug. The FIP-L1-PDGFRA fusion gene cooperates with IL-5 overexpression in a murine model of HES, suggesting that both pathogenic events cooperate in disease etiology.[71] The patients generally responsive to imatinib are those most characteristic of “classic” HES, namely males between the ages of 20-50 who present clinically with marked peripheral blood eosinophilia. Recently, these patients have been shown to meet minor criteria for systemic mastocytosis, having elevated levels of serum mast cell tryptase, and high numbers of dysplastic mast cells in the bone marrow.[72,73] These patients go on to develop eosinophilic endomyocardial disease with embolization to peripheral organs including the extremities and the brain, and they strikingly resemble the patients originally designated by Hardy and Anderson.[61] However, it appears that any disease that results in prolonged and marked eosinophilia can be associated with endomyocardial disease. For example, endomyocardial disease has occurred during the course of helminth infections and also in various malignancies associated with marked eosinophilia.[74-76] Thus, patients with marked eosinophilia are at risk for the development of cardiac disease regardless of the underlying etiology of the eosinophilia. Accordingly, routine surveillance of the cardio-respiratory system (e.g. echocardiograms and plethysmography) in patients with EGID and peripheral blood eosinophilia is warranted. Based on these concerns, the diagnosis of HES in patients with EGID should always be considered especially in patients who develop extra-gastrointestinal manifestations (e.g. splenomegaly, or cutaneous, cardiac, or respiratory systems). As such, additional diagnostic testing for HES should be considered including bone marrow analysis (searching for evidence of myelodysplasia), serum mast cell tryptase and vitamin B12 levels (both moderately elevated in classic HES), and genetic analysis for the presence of the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion event.[72]

GASTROINTESTINAL EOSINOPHILIA FROM KNOWN CAUSES

There are a variety of other known causes of GI eosinophilia, including parasitic infections, other allergic disorders, gastrointestinal reflux disease (GERD), inflammatory bowel diseases, drug reactions, malignancy, Churg-Stauss syndrome, celiac disease, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and solid organ transplantation. Among those causes, parasitic infections are the most common cause of gastrointestinal eosinophilia in developing countries. In developed countries, allergic causes have become the dominant cause for gastrointestinal eosinophilia. Among the infectious causes of gastrointestinal eosinophilia, aside from the number one cause parasitic infections, helicobacter pylori infection has also been reported. Medications causing GI eosinophilia include gold salts, azathioprine, gemfibrozil, enalapril, carbamazepine clofazimine and cotrimoxazole. In the Churg-Strauss syndrome and polyarteritis nodosa, characterized findings include eosinophilic infiltrate involving the small vessels in the intestinal tract and other organs. In IBD, eosinophils usually represent only a small percentage of the infiltrating leukocytes,[77,78] but their level has been proposed to be a negative prognostic indicator.[78,79]

CONCLUSION

Gastrointestinal eosinophilia, as a broad term for abnormal eosinophil accumulation in the GI tract, involves many different disease identities. These diseases include primary eosinophil associated gastrointestinal diseases, gastrointestinal eosinophilia in HES and all gastrointestinal eosinophilic states associated with known causes. Although each of these diseases has its unique features, it is important to recognize that there is no absolute boundary between them. As an example, HES is a systemic eosinophilic disease but it may also involve the gastrointestinal tract and not be associated with apparent causes as in primary gastrointestinal eosinophilia. Similarly, primary EGID has a strong association with allergy, yet it is generally not considered a secondary eosinophilia. Indeed, different disease mechanisms likely account for these various states. For example, the eosinophilic esophagitis appears to be primarily driven by IL-5 and eotaxin-3, whereas evidence is emerging that eosinophilic enteritis may be primarily driven by eotaxin-1. As such, targeted therapy with anti-eotaxins, eotaxin receptor blockers (e.g. CCR3 antagonists), or humanized anti-IL-5 therapeutics are likely to be useful therapy in the future. Indeed, early clinical trials have supported their potential utility[60] .

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Andrea Lippelman for her help during the writing of this chapter. This work was supported by NIH AI 45898-09, AI 070235-02, T32 DK 07727-12, The Buckeye Foundation, Campaign Urging Research for Eosinophilic Diseases (CURED) Foundation, and The Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network (FAAN). We acknowledge that this chapter was adopted in large part from our prior publication.[80]

This work was supported by NIH AI 45898-09, NIH AI 070235-02 and T32 DK 07727-12.

Abbreviations

- ECP

Eosinophil cationic protein

- EDN

Eosinophil derived neurotoxin

- EE

Eosinophilic esophagitis

- EGID

Eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders

- EPO

Eosinophil peroxidase

- GERD

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- GI

Gastrointestinal

- GM-CSF

Granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor

- HES

Hypereosinophilic syndrome

- IBD

Inflammatory bowel disease

- LTC

Cysteinyl leukotriene

- MBP

Major Basic Protein

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kato M, Kephart GM, Talley NJ, et al. Eosinophil infiltration and degranulation in normal human tissue. Anat Rec. 1998;252(3):418–425. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199811)252:3<418::AID-AR10>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mishra A, Hogan SP, Lee JJ, et al. Fundamental signals regulate eosinophil homing to the gastrointestinal tract. J Clin Invest. 1999;103(12):1719–1727. doi: 10.1172/JCI6560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rothenberg ME, Mishra A, Brandt EB, et al. Gastrointestinal eosinophils. Immunol Rev. 2001;179:139–155. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.790114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Straumann A, Kristl J, Conus S, et al. Cytokine expression in healthy and inflamed mucosa: probing the role of eosinophils in the digestive tract. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11(8):720–726. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000172557.39767.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gleich GJ, Frigas E, Loegering DA, et al. Cytotoxic properties of the eosinophil major basic protein. J Immunol. 1979;123(6):2925–2927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gleich GJ, Adolphson CR. The eosinophilic leukocyte: structure and function. Adv Immunol. 1986;39:177–253. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60351-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slifman NR, Loegering DA, McKean DJ, et al. Ribonuclease activity associated with human eosinophil-derived neurotoxin and eosinophil cationic protein. J Immunol. 1986;137(9):2913–2917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenberg HF, Dyer KD, Tiffany HL, et al. Rapid evolution of a unique family of primate ribonuclease genes. Nat Gene. 1995;10(2):219–223. doi: 10.1038/ng0695-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vanderhoof JA, Young RJ, Hanner TL, et al. Montelukast: use in pediatric patients with eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;36(2):293–294. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200302000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacoby DB, Gleich GJ, Fryer AD. Human eosinophil major basic protein is an endogenous allosteric antagonist at the inhibitory muscarinic M2 receptor. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:1314–1318. doi: 10.1172/JCI116331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kita H. The eosinophil: a cytokine-producing cell? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996;9(4):889–892. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(96)80061-3. 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gharaee-Kermani M, Phan SH. The role of eosinophils in pulmonary fibrosis. Int J Mol Med. 1998;1:43–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phipps S, Ying S, Wangoo A, et al. The relationship between allergen-induced tissue eosinophilia and markers of repair and remodeling in human atopic skin. J Immunol. 2002;169(8):4604–4612. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lucey DR, Nicholson WA, Weller PF. Mature human eosinophils have the capacity to express HLA-DR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86(4):1348–1351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.4.1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lacy P, Levi-Schaffer F, Mahmudi-Azer S, et al. Intracellular localization of interleukin-6 in eosinophils from atopic asthmatics and effects of interferon gamma. Blood. 1998;91(7):2508–2516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi HZ, Humbles A, Gerard C, et al. Lymph node trafficking and antigen presentation by endobronchial eosinophils. J Clin Invest. 2000;105(7):945–953. doi: 10.1172/JCI8945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mattes J, Yang M, Mahalingam S, et al. Intrinsic defect in T cell production of interleukin (IL)-13 in the absence of both IL-5 and eotaxin precludes the development of eosinophilia and airways hyperreactivity in experimental asthma. J Exp Med. 2002;195(11):1433–1444. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis RA, Austen KF, Soberman RJ. Leukotrienes and other products of the 5-lipoxygenase pathway. Biochemistry and relation to pathobiology in human diseases. N Engl J Med. 1990;323(10):645–655. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199009063231006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Torpier G, Colombel JF, Mathieu-Chandelier C, et al. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: ultrastructural evidence for a selective release of eosinophil major basic protein. Clin Exp Immunol. 1988;74(3):404–408. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klein NC, Hargrove RL, Sleisenger MH, et al. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Medicine. 1970;2:215–225. doi: 10.1097/00005792-197007000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cello JP. Eosinophil gastroenteritis: a complex disease entity. Am J Med. 1979;67:1097–1114. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(79)90652-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noel RJ, Putnam PE, Collins MH, et al. Clinical and immunopathologic effects of swallowed fluticasone for eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2(7):568–575. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00240-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khan S, Orenstein SR. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: epidemiology, diagnosis and management. Paediatr Drugs. 2002;4(9):563–570. doi: 10.2165/00128072-200204090-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caldwell JH, Tennerbaum JI, Bronstein HA. Serum IgE to eosinophilic gastroenteritis. N Engl J Med. 1975;292:1388–1390. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197506262922608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scudamore HH, Phillips SF, Swedlund HA, et al. Food allergy manifested by eosinophilia, elevated immunoglobulin E level, and protein-losing enteropathy: The syndrome of allergic gastroenteropathy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1982;70:129–136. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(82)90241-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Furuta GT, Ackerman SJ, Wershil BK. The role of the eosinophil in gastrointestinal diseases. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 1995;11:541–547. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iacono G, Carroccio A, Cavataiio F, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux and cows milk allergy in infants: a prospective study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996;97:822–827. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(96)80160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sampson HA. Food Allergy. JAMA. 1997;278:1888–1894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walsh SV, Antonioli DA, Goldman H, et al. Allergic esophagitis in children: a clinicopathological entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23(4):390–396. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199904000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spergel J, Rothenberg ME, Fogg M. Eliminating eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Immunol. 2005;115(2):131–132. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kelly KJ, Lazenby AJ, Rowe PC, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis attributed to gastroesophageal reflux: improvement with an amino acid-based formula. Gastroenterology. 1995;109(5):1503–1512. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90637-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oyaizu N, Uemura Y, Izumi H, Morii S, Nishi M, Hioki K. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: Immunohistochemical evidence for IgE mast cell-mediated allergy. Act Pathol Jpn. 1985;35:759–766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bischoff SC. Mucosal allergy: role of mast cells and eosinophil granulocytes in the gut. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol. 1996;10(3):443–459. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3528(96)90052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rothenberg ME, Mishra A, Brandt EB, et al. Gastrointestinal eosinophils in health and disease. Adv Immunol. 2001;78:291–328. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(01)78007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sampson HA. Food allergy. Part 1: immunopathogenesis and clinical disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103(5):717–728. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70411-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fox VL, Nurko S, Furuta GT. Eosinophilic esophagitis: It's not just kid's stuff. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56(2):260–270. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(02)70188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bates B. ‘Explosion’ of eosinophilic esophagitis in children. Pediatr News. 2000;34:4. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Croese J, Fairley SK, Masson JW, et al. Clinical and endoscopic features of eosinophilic esophagitis in adults. Gastrointestinal Endosc. 2003;58(4):516–522. doi: 10.1067/s0016-5107(03)01870-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cury EK, Schraibman V, Faintuch S. Eosinophilic infiltration of the esophagus: gastroesophageal reflux versus eosinophilic esophagitis in children--discussion on daily practice. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39(2):e4–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2003.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Attwood SE, Smyrk TC, Demeester TR, et al. Esophageal eosinophilia with dysphagia. A distinct clinicopathologic syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38(1):109–116. doi: 10.1007/BF01296781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cantu P, Velio P, Prada A, et al. Ringed oesophagus and idiopathic eosinophilic oesophagitis in adults: an association in two cases. Dig Liver Dis. 2005;37(2):129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fujiwara H, Morita A, Kobayashi H, et al. Infiltrating eosinophils and eotaxin: their association with idiopathic eosinophilic esophagitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;89(4):429–432. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Munitiz V, Martinez de Haro LF, Ortiz A, et al. Primary eosinophilic esophagitis. Dis Esophagus. 2003;16(2):165–168. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2050.2003.00319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lucendo Villarin AJ, Carrion Alonso G, Navarro Sanchez M, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in adults, an emerging cause of dysphagia. Description of 9 cases. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2005;97(4):229–239. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082005000400003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Straumann A, Simon HU. The physiological and pathophysiological roles of eosinophils in the gastrointestinal tract. Allergy. 2004;59(1):15–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1398-9995.2003.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruchelli E, Wenner W, Voytek T, Brown K, Liacouras C. Severity of esophageal eosinophilia predicts response to conventional gastroesophageal reflux therapy. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 1999;2(1):15–18. doi: 10.1007/s100249900084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kukuruzovic RH, Elliott EE, O'Loughlin EV, et al. Non-surgical interventions for eosinophilic oesophagitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD004065. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004065.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fox VL, Nurko S, Furuta GT. Eosinophilic esophagitis: it's not just kid's stuff. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56(2):260–270. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(02)70188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Noel RJ, Putnam PE, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilic esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(9):940–941. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200408263510924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Walker NI, Croese J, Clouston AD, et al. Eosinophilic enteritis in northeastern Australia. Pathology, association with Ancylostoma caninum, and implications. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19(3):328–337. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199503000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Al Samman M, Haque S, Long JD. Strongyloidiasis colitis: a case report and review of the literature. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;28(1):77–80. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199901000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Straumann A, Spichtin HP, Bucher KA, Heer P, Simon HU. Eosinophilic esophagitis: red on microscopy, white on endoscopy. Digestion. 2004;70(2):109–116. doi: 10.1159/000080934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee JH, Rhee PL, Kim JJ, et al. The role of mucosal biopsy in the diagnosis of chronic diarrhea: value of multiple biopsies when colonoscopic finding is normal or nonspecific. Korean J Intern Med. 1997;12(2):182–187. doi: 10.3904/kjim.1997.12.2.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.DeBrosse CW, Case JW, Putnam PE, et al. Quantity and Distribution of Eosinophils in the Gastrointestinal Tract of Children. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2006;9:210–218. doi: 10.2350/11-05-0130.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lowichik A WA. A quantitative evaluation of mucosal eosinophils in the pediatric gastrointestinal tract. Mod Pathol. 1996;9(2):110–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ngo P, Furuta GT, Antonioli DA, et al. Eosinophils in the esophagus--peptic or allergic eosinophilic esophagitis? Case series of three patients with esophageal eosinophilia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(7):1666–1670. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Justinich C, Katz A, Gurbindo C, et al. Elemental diet improves steroid-dependent eosinophilic gastroenteritis and reverses growth failure. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1996;23(1):81–85. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199607000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Quack I, Sellin L, Buchner NJ, Theegarten D, Rump LC, Henning BF. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis in a young girl--long term remission under Montelukast. BMC Gastroenterol. 2005;5:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-5-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Foroughi S, Prussin C. Clinical management of eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2005;5(4):259–261. doi: 10.1007/s11882-005-0062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Garrett JK, Jameson SC, Thomson B, et al. Anti-interleukin-5 (mepolizumab) therapy for hypereosinophilic syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113(1):115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Blanchard C, Mishra A, Saito-Akei H, et al. Inhibition of human interleukin-13-induced respiratory and oesophageal inflammation by anti-human-interleukin-13 antibody (CAT-354) Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35(8):1096–1103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chusid MJ, Dale DC, West BC, et al. The hypereosinophilic syndrome: analysis of fourteen cases with review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1975;54(1):1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Roufosse F, Cogan E, Goldman M. The hypereosinophilic syndrome revisited. Annu Rev Med. 2003;54:169–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.54.101601.152431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Simon HU, Plotz SG, Dummer R, et al. Abnormal clones of T cells producing interleukin-5 in idiopathic eosinophilia. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(15):1112–1120. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910073411503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cools J, DeAngelo DJ, Gotlib J, et al. A tyrosine kinase created by fusion of the PDGFRA and FIP1L1 genes as a therapeutic target of imatinib in idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(13):1201–1214. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cortes J, Ault P, Koller C, et al. Efficacy of imatinib mesylate in the treatment of idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. Blood. 2003;20:20. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schaller JL, Burkland GA. Case report: rapid and complete control of idiopathic hypereosinophilia with imatinib mesylate. MedGenMed. 2001;3(5):9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ault P, Cortes J, Koller C, Kaled ES, Kantarjian H. Response of idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome to treatment with imatinib mesylate. Leuk Res. 2002;26(9):881–884. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(02)00046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gleich GJ, Leiferman KM, Pardanani A, et al. Treatment of hypereosinophilic syndrome with imatinib mesilate. Lancet. 2002;359(9317):1577–1578. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08505-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Griffin JH, Leung J, Bruner RJ, et al. Discovery of a fusion kinase in EOL-1 cells and idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(13):7830–7835. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0932698100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yamada Y, Rothenberg ME, Lee AW, et al. The FIP1L1-PDGFR{alpha} fusion gene cooperates with IL-5 to induce murine hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES)/chronic eosinophilic leukemia (CEL)-like disease. Blood. 2006;107:4071–4079. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Klion AD, Noel P, Akin C, et al. Elevated serum tryptase levels identify a subset of patients with a myeloproliferative variant of idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome associated with tissue fibrosis, poor prognosis, and imatinib responsiveness. Blood. 2003;101(12):4660–4666. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Klion AD, Robyn JA, Akin C, et al. Molecular remission and reversal of myelofibrosis in response to imatinib mesylate treatment in patients with the myeloproliferative variant of hypereosinophilic syndrome. Blood. 2003;101:4660–4666. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yoshida T, Naganuma T, Niizawa M, et al. A case of eosinophilic gastroenteritis accompanied by perimyocarditis, which was strongly suspected. Nippon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1995;92(8):1183–1188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hussain A, Brown PJ, Thwaites BC, et al. Eosinophilic endomyocardial disease due to high grade chest wall sarcoma. Thorax. 1994 Oct;49(10):1040–1041. doi: 10.1136/thx.49.10.1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Andy JJ, Ogunowo PO, Akpan NA, Odigwe CO, Ekanem IA, Esin RA. Helminth associated hypereosinophilia and tropical endomyocardial fibrosis (EMF) in Nigeria. Acta Trop. 1998;69(2):127–140. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(97)00125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Walsh RE, Gaginella TS. The eosiniophil in inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1991;26:1217–1224. doi: 10.3109/00365529108998617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Desreumaux P, Nutten S, Colombel JF. Activated eosinophils in inflammatory bowel disease: do they matter? Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(12):3396–3398. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nishitani H, Okabayashi M, Satomi M, et al. Infiltration of peroxidase-producing eosinophils into the lamina propria of patients with ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol. 1998;33(2):189–195. doi: 10.1007/s005350050068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders (EGID) J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113(1):11–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]