Abstract

We previously reported that selected mutations of highly conserved arginine residues within the LLP regions of HIV-1ME46 gp41 had diverse effects on Env function. In the current study, we sought to test if the observed LLP mutant phenotypes would be similar in HIV-189.6. The results of the current studies revealed that the LLP-1 mutations conferred reduced Env incorporation, infectivity, and replication phenotypes in both viruses, while homologous LLP-2 mutations had differential phenotypical effects between the two strains. In particular, several of the 89.6 LLP-2 mutant viruses were replication defective in CEMX174 cells despite having increased levels of Env incorporation, and with both strains, there were differential effects on infectivity. This comparison of homologous point mutations in two different strains of HIV supports the role of LLPs as determinants of Env function, but reveals for the first time the influence of virus strain on LLP mutant phenotypes.

Keywords: Site-directed mutagenesis, Cell fusion, HIV envelope protein gp41, HIV, Viral infectivity, Virus Replication, HIV envelope incorporation and biosynthesis

Introduction

The envelope protein of the HIV and SIV lentiviruses consist of the surface unit (SU) gp120 and transmembrane (TM) gp41 proteins. The SU protein binds the host cellular CD4 receptor and a chemokine coreceptor, while the TM protein mediates fusion to permit virion entry into the cell (Hunter, 1997; Wyatt and Sodroski, 1998). Compared to other member of the Retroviridae family, the TM of lentiviruses is distinguished by the presence of a relatively long intracytoplasmic domain (ICD) of about 150−200 amino acid residues. The Env ectodomains have been the main focus as determinants of Env-related phenotypes, especially with the availability of the crystal structures for these protein sequences (Chan et al., 1997; Kwong et al., 2000; Rizzuto et al., 1998; Weissenhorn et al., 1997; Yang et al., 1999). Until relatively recently, the ICD segments of HIV and SIV Env were believed to be dispensable, as truncation mutants lacking ICD were found to replicate in cell culture (Chakrabarti et al., 1989; Hirsch et al., 1989; Kodama et al., 1989; Wilk et al., 1992). In contrast, other early in vitro studies of the HIV ICD indicated that the ICD is indeed important to Env function (Dubay et al., 1992; Gabuzda et al., 1992; Yu et al., 1993), but these latter reports gained little attention.

Over the last decade, however, numerous studies have identified the ICD as a critical determinant of Env function and structure, including the role of Env in viral replication, infectivity, cytopathicity, pathogenicity, and immunogenicity, thus providing compelling evidence for the importance of the ICD in Env structure and function in vitro and in vivo (Blot et al., 2003; Bultmann et al., 2001; Day et al., 2004; Edwards et al., 2002; Egan et al., 1996; Luciw et al., 1998; Wyss et al., 2005; Ye et al., 2004). For example, several studies have reported a critical role for the HIV ICD in virion assembly by interactions with the Matrix (MA) protein of Gag, particularly with the observation that mutations in the MA region that result in defects in Env incorporation or virus infectivity can be restored by compensatory mutations in the gp41 ICD (Freed and Martin, 1995; Freed and Martin, 1996; Mammano et al., 1995; West et al., 2002). Another report demonstrated that mutations in the gp41 ICD that disrupt Env incorporation can be reversed by mutations in the MA gene (Murakami and Freed, 2000a). Recent studies also indicate that Gag processing and Env interactions are coupled to control the fusion activity of Env to prevent infection by immature virus particles and that the down-regulation of Gag by the ICD is likely an important regulatory step during virus assembly and budding (Chan and Chen, 2006; Murakami et al., 2004; Wyma et al., 2004; Wyma et al., 2000).

In addition to ICD interaction with Gag, the ICD of HIV and SIV have been shown to play a role in Env neutralization sensitivity (Edwards et al., 2001; Edwards et al., 2002; Kalia et al., 2005; Vzorov et al., 2005; Ye et al., 2004; Yuste et al., 2005). For example, the truncation of the HIV ICD has been shown to increase the neutralization sensitivity of the Env protein, evidently by exposing neutralizing epitopes that are in full-length Env sequestered from antibody recognition, suggesting an important role for the ICD in immune evasion in vivo (Edwards et al., 2001; Edwards et al., 2002). Other studies have demonstrated that the ICD of HIV or SIV is an important determinant of Env incorporation into virions and that changes within the ICD can have an effect on the stability of the gp120-gp41 complex (Affranchino and Gonzalez, 2006; Akari et al., 2000; Celma et al., 2001; Kalia et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2002; Manrique et al., 2001; Murakami and Freed, 2000b; Piller et al., 2000; Yuste et al., 2005; Yuste et al., 2004; Zingler and Littman, 1993). Supporting these in vitro studies is the observation that the ICD is a critical locus of attenuation of SIV during experimental infections of rhesus macaques (Luciw et al., 1992; Marthas et al., 1989; Shacklett et al., 2002; Shacklett et al., 2000). In addition, occasional reversions of stop codons in the ICD and the resultant expression of full length Env is associated with a rapid and marked increase in viral load and progression to SAIDS (Luciw et al., 1998).

The ICD of HIV also contains a number of highly conserved sequence motifs that likely play a role in its functional activities. Two such sequences, YXXΦ and dileucine, are characteristic of protein endocytic and trafficking signals and may function in to down regulate the cell surface exposure and immune recognition of Env (Boge et al., 1998; Egan et al., 1996; Ohno et al., 1997; Rowell et al., 1995; Wyss et al., 2001; Ye et al., 2004). In addition to the YXXΦ and dileucine motifs, the ICD is predicted to contain two highly positively charged amphipathic α-helical segments, LLP-1 and LLP-2, that are linked by a neutral leucine zipper-like motif (LLP-3) to form an extended helical structure modeled to be closely associated with the lipid bilayer (Eisenberg and Wesson, 1990; Hunter and Swanstrom, 1990; Kliger and Shai, 1997; Miller et al., 1991; Venable et al., 1989). Recent investigations of the role of the ICD sequences in HIV-1 infectivity and replication have demonstrated the potential importance of these regions to the viral life cycle. For example, certain positive to negative charge substitutions within the LLP-1 sequence were shown to reduce viral infectivity and Env incorporation (Kalia et al., 2003; Piller et al., 2000). Other amino acid substitutions or deletions within this same sequence also reduced Env incorporation and infectivity, and in certain cases, targeted Env for degradation (Lee et al., 2002). With regard to LLP-2, it was recently demonstrated that truncation of the ICD within this region resulted in an increase in cell-to-cell fusion suggesting a mechanism by which the interaction of LLP-2 with the cellular membrane serves to restrain the membrane disruptive potential of Env (Wyss et al., 2005). Moreover, the region of the ICD containing the LLP sequences is proposed to play a role in the interaction between Env and the Gag protein and to affect Env incorporation into virus particles (Celma et al., 2001; Cosson, 1996; Freed and Martin, 1996; Murakami and Freed, 2000a; Piller et al., 2000). Within LLP-3, a diaromatic sequence was shown to be responsible for the targeting of Env to the trans-Golgi network and thus important for Env incorporation into virions and infectivity (Blot et al., 2003; Lopez-Verges et al., 2006).

In a recent report, positive to negative charge substitutions were introduced into the LLP-1 (MX1, R846E and R848E) and LLP-2 (MX2, R770E and R788E) regions of ME46, a dual tropic primary isolate of HIV-1 (Kalia et al., 2003). The rationale behind these substitutions is based on the observation that truncations of the ICD can induce major conformational alterations in Env and that amino acid substitutions may provide a more specific modification to evaluate alterations in Env function. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that specific point mutations of arginine to glutamic acid residues can substantially alter the membrane disrupting activities of the LLP peptide sequences (Miller et al., 1993; Tencza et al., 1995). Incorporation of the R846E and R848E mutations in the LLP-1 region of ME46 resulted in a virus that showed a substantial decrease in infectivity, replication capacity, and Env incorporation, despite the fact that intracellular Env expression and processing were normal. Similar point mutations made in the LLP-2 of ME46 revealed a novel mutant that replicated to parental levels and displayed parental levels of Env incorporation into virus particles. However, the mutant LLP-2 virus was reduced in its ability to induce syncytia, and this phenotype was directly correlated to a reduction in Env mediated cell-to-cell fusion (Kalia et al., 2003). In a subsequent study, it was demonstrated that changes within the LLP-2 region of ME46 could induce subtle, yet statistically significant alterations in the conformation and neutralization sensitivity of both gp120 and gp41, suggesting allosteric effects of the ICD on Env conformation (Kalia et al., 2005).

In the current study, we introduced these LLP point mutations alone or in combination in the context of a related, but distinct primary dual-tropic isolate of HIV-1, 89.6, to determine if homologous LLP mutations would confer phenotypes similar to those observed with ME46. Our results demonstrate that the LLP regions are critical, conserved structural motifs that play vital roles in viral envelope function, and that minor alterations within these motifs can produce profound changes in viral phenotypes. However, the effects of some of these LLP mutations differ between ME46 and 89.6, indicating that the phenotypic changes can be dependent on the context of the mutations within a given specific viral envelope species.

Results

Rationale and construction of ME46 and 89.6 ICD mutants.

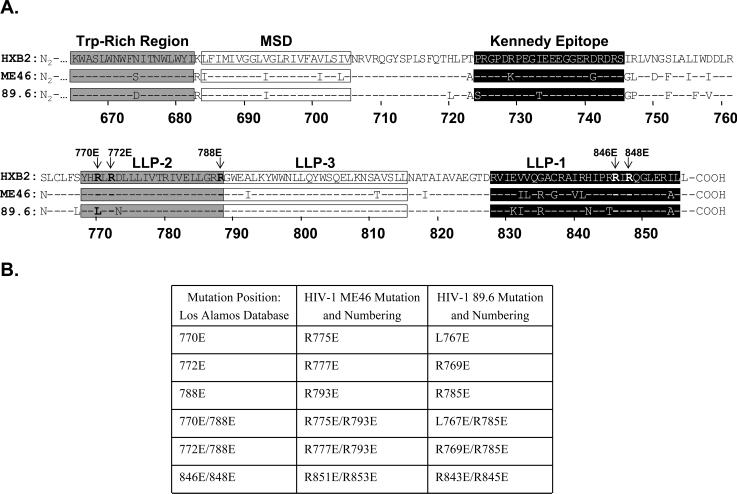

The HIV-1 strains, ME46, and 89.6, are both dual tropic clade B isolates that have been described previously (Chen et al., 1997; Collman et al., 1992; Doranz et al., 1996). In a previous study, a pair of arginine to glutamic acid residue substitutions were introduced into the LLP-2 (770E/788E) and LLP-1 (843E/845E) regions of ME46 based on the fact that these positively charged residues are highly conserved, are present on the hydrophilic face of the predicted amphipathic α-helical structure of these peptide segments, and are important for the membrane perturbing properties of the peptide sequences (Kalia et al., 2003; Miller et al., 1993; Tencza et al., 1999; Tencza et al., 1995). In the context of proviral mutant clones, it has been demonstrated that charge substitutions can influence Env function (Kalia et al., 2003; Piller et al., 2000). For the current study, the positions of the introduced mutations into ME46 and 89.6 relative to their positions in the HXB2 reference strain are shown in Figure 1A, and a summary of the panel of mutant viruses bearing one or more of these mutations is outlined in Figure 1B. The ME46 virus that contains the 770E and 788E modifications in LLP-2 represented a novel ICD mutant that displays similar replication properties to the parental virus, but was shown to be defective in cellular cytopathicity (Kalia et al., 2003). These LLP-2 mutations were introduced alone or in combination into 89.6 (Fig. 1B). However, because 89.6 contains a leucine at position 770 (Fig. 1A), a second double mutant, 772E/788E, was constructed with both viruses to determine if the reduced cytopathicity was dependent on the location of the glutamic acid substitutions. Additionally, the 846E and 848E pair of mutations was incorporated into 89.6 LLP-1 to asses the strain specificity of the conferred phenotypes of these mutations that resulted in a loss of ME46 replication competence and a defect in Env incorporation (Kalia et al., 2003). The proviral DNA for all six mutant viruses and both parental viruses were individually transfected into 293T cells to produce virus stocks for the assays described below.

Figure 1. HIV ICD Structure and positions of amino acid changes.

A) The linear sequences of gp41 from the HXB2 reference strain (GenBank #NC 001802), ME46 (GenBank #AY669722), and 89.6 (GenBank #U39362) are shown starting with the tryptophan-rich region (Trp-Rich Region). The amino acid residue numbering at the bottom is based on the HXB2 strain. The dashed lines in the ME46 and 89.6 sequences represent sequence identity with that of HXB2. The Trp-Rich region is followed by the membrane spanning domain (MSD) (Gallaher et al., 1989). Downstream of this region is the Kennedy epitope that is recognized by neutralizing antibodies (Kennedy et al., 1986). Lentiviral lytic peptide (LLP) regions 1 and 2 have been shown as peptides to assume an amphipathic α-helical structures in membrane like environments and to have potent anti-microbial activities (Gawrisch et al., 1993; Miller et al., 1993; Miller et al., 1991; Srinivas et al., 1992; Tencza et al., 1999; Tencza et al., 1997). A third region (LLP-3) also has anti-microbial activity and contains a leucine-zipper like sequence (Kliger and Shai, 1997). The glutamic acid substitutions made on the hydrophilic face of the LLP-2 and LLP-1 regions were introduced alone or in combination into ME46 and 89.6, are indicated by an arrow and the residue position. B) The mutations that were introduced alone or in combination into ME46 and 89.6 are summarized in the table. The LLP-2 and LLP-1 sequences from ME46 and 89.6 were located in the HXB2 reference strain using the HIV/SIV Sequence Locator Tool at the Los Alamos Sequence Database (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/hiv-db/LOCATE/locate.html) to determine the position of the mutations relative to HXB2 (left hand column). Strain specific numbering and changes for ME46 and 89.6 are shown in the center and right hand columns, respectively. The amino acid carried by the parental virus is indicated first, followed by its position in the Env protein and the mutant amino acid residue. The HXB2 numbering in the left hand column is used throughout the rest of the text.

Effect of LLP mutations on viral infectivity in TZM-bl indicator cells.

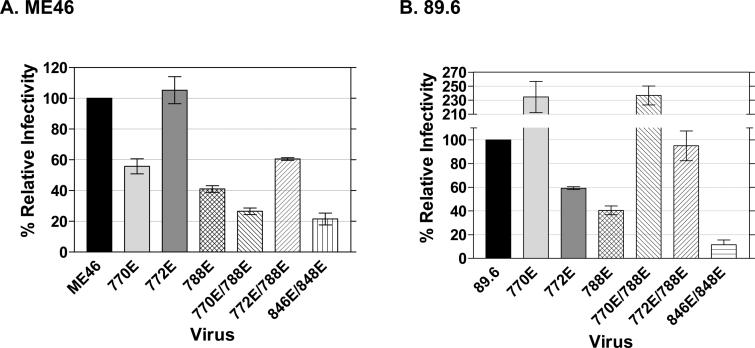

To determine if the introduced mutations had an effect on viral infectivity in a single round of replication, TZM-bl indicator cells were infected in parallel with either the parental virus or one of the mutant derivatives, and 48 hours post-infection, β-galactosidase activity was assayed as described in Materials and Methods. The average light intensity units (LIU) for each mutant derivative are expressed as percent relative infectivity compared to the parental virus (Fig. 2). For both virus strains, the combination of the LLP-1 846E and 848E mutations resulted in a defect in the ability of the mutant viruses to infect TZM-bl cells (Fig. 2). In contrast, differential infectivity phenotypes were observed between the two viruses with the LLP-2 mutations. The 770E mutation conferred a 2-fold reduction in infectivity in ME46 (Fig. 2A), while the same mutation in 89.6 resulted in a virus that demonstrated a greater than 2-fold increase in infectivity compared to the parental virus (Fig. 2B). In ME46, a reduction in infectivity conferred by the 788E mutation was additive to that of the 770E mutation (770E/788E, Fig 2A). While the 788E mutation also showed a greater than 2-fold reduction in mutant 89.6 infectivity, there was no additive inhibition when combined with the additional 770E mutation (Fig 2B). Interestingly, the 772E and 788E mutations individually resulted in 89.6 mutant derivatives that were decreased in infectivity by 40−50%, but the mutant 89.6 virus with both changes displayed parental levels of infectivity. In contrast, the negative effect of the 788E mutation on ME46 infectivity was not reversed in combination with the 772E mutation, despite the fact that the ME46 mutant derivative with only the 772E mutation showed parental levels of infectivity (Fig. 2A). These results demonstrate the differential effects of specific LLP-2 mutations in the two viral strains on infectivity as measured in TZM-bl cells.

Figure 2. Infectivity of HIV ME46 and 89.6 mutant viruses as measured in TZM-bl indicator cells.

TZM-bl indicator cells, which are stably transduced to express CD4, both co-receptors, and both luciferase and β-galactosidase (β-gal) genes that are under control of the HIV-1 LTR (Derdeyn et al., 2000; Wei et al., 2002), were infected with the indicated virus after p24 level normalization. After 48 h post-infection, cells were lysed with the Beta-Glo Assay System reagent (Promega, Madison, WI), and β-gal activity was measured using a Veritas microplate luminometer. An average light intensity unit (LIU) for each mutant was compared to the respective parental virus (relative infectivity) in three to four independent experiments each done in quadruplicate. Error bars represent the standard error of measurement (SEM). A) Infectivity of ME46 mutant viruses relative to the ME46 parental virus. B) 89.6 mutant virus infectivity relative to the 89.6 parental virus.

Differential replication competence of the LLP mutant derivatives in the CEMX174 cell line and primary human PBMC.

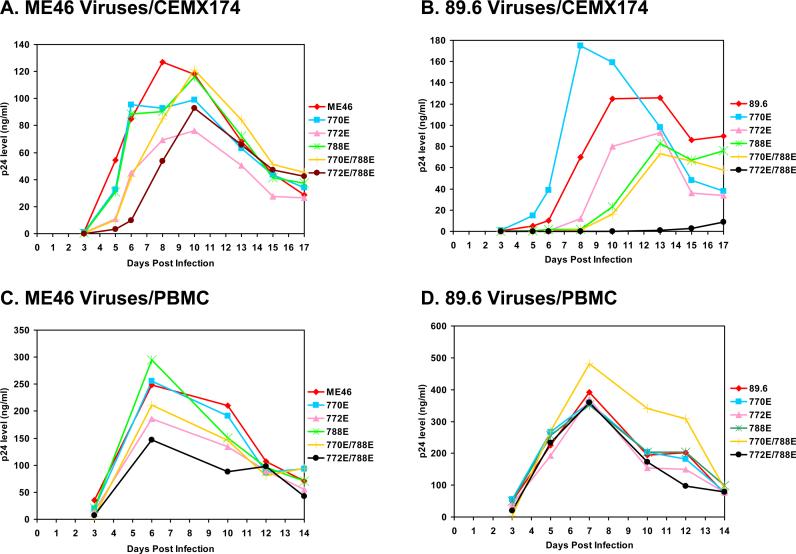

The ability of the mutant derivatives to establish a productive infection in the CEMX174 cell line and the more biologically relevant human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) was determined. For both cell types, similar amounts of virus based on the p24 content of the viral stocks were used to infect the cells, and replication levels were determined by measuring p24 production in the supernatant. The ME46 and 89.6 viruses with both the 846E and 848E LLP-1 mutations were not able establish a productive infection in CEMX174 cells (data not shown). As with the single cycle infectivity data, the LLP-2 mutations had differential effects on the replication competence of the two strains. Three of the LLP-2 ME46 mutant derivatives (770E, 788E, and 770E/788E) replicated to parental levels in CEMX174 cells (Fig 3A). The ME46 772E/788E mutant showed slightly delayed replication kinetics, but the amount of virus produced by day 10 was near parental virus levels. Only the ME46 772E mutant displayed a consistent average 2-fold reduction in replication in CEMX174 cells compared to parental ME46 on days 6, 8, and 10. In contrast, the various 89.6 LLP-2 mutants displayed a broader range of replication kinetics compared to the parental virus. At one end of the spectrum, the double 772E/788E mutant 89.6 virus was replication defective in CEMX174 cells (Fig. 3B). In the middle of the spectrum, the 772E, the 788E, and 770E/788E mutations in 89.6 LLP-2 resulted in viruses with delayed and reduced replication kinetics relative to the parental 89.6 virus (Fig. 3B). At the other end of the spectrum, the 770E mutation in 89.6 appeared to increase the peak levels of virus replication by about 30% relative to the parental virus at their respective peaks of virus production in the CEMX174 cells (Fig 3B). These replication patterns were reproducible in 2−3 independent assays.

Figure 3. Replication kinetics in the CEMX174 cell line and human PBMC.

CEMX174 cells or human PBMC were infected with each of the indicated viruses that were normalized to p24 levels, and the respective cultures were maintained as described Materials and Methods. At periodic intervals, viral supernatants were harvested, and the level of p24 production was determined using a p24 ELISA kit. A and B: Replication kinetics of ME46 and 89.6 and mutant derivative viruses in CEMX174 cells, respectively. C and D: Replication kinetics of ME46 and 89.6 and mutant derivative viruses in human PBMC, respectively. The replication kinetics for each virus is identified by the legend to the right of each graph. The graphs are representative of at least two independent experiments.

With human PBMC, it was observed that ME46 and 89.6 viruses with the combination of the LLP-1 846E and 848E were unable to establish a productive infection, in agreement with the results from CEMX174 cells (Kalia et al., 2003, data not shown). In contrast, the mutant LLP-2 ME46 and 89.6 viruses were all replication competent in PBMC. With the ME46 LLP2 mutants, the 772E, 770E/778E, and 772E/788E mutants reduced the apparent peak levels of virus production relative to parental ME46 by approximately 20−40%, while the remaining LLP-2 mutants displayed replication levels similar to parental ME46. All of the 89.6 LLP-2 mutant viruses displayed virtually identical replication kinetics and levels compared to parental 89.6, with only the 770E/788E mutant displaying virus production that was about 25% above that observed with the parental 89.6 virus. Taken together, these results indicated that both cell type and Env specificity can have a differential effect on the observed replication phenotype for the LLP-2 mutants, in contrast to the consistent effect of LLP-1 mutations.

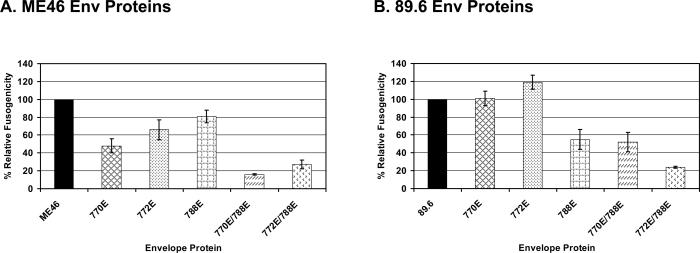

Cell-to-cell fusion mediated by 89.6 and ME46 LLP-2 Env mutant proteins.

Based on our previous observations of LLP-2 mutations affecting viral syncytium formation and fusion activity (Kalia et al., 2003), a quantitative luciferase based cell-to-cell fusion assay was used to independently measure the fusion properties of Env apart from viral replication and the other viral proteins (Edwards et al., 2002; Rucker et al., 1997). For this assay, 293T effector cells expressing the test Env protein were mixed with QT6 target cells expressing the CD4 receptor and the CXCR4 co-receptor. Syncytium formation was allowed overnight, and on the following day, luciferase activity was measured from the cell lysate. The results of these assays demonstrated that most of the LLP-2 mutations in ME46 reduced the fusogenicity of the Env protein relative to the parental viral Env (Fig. 4A). ME46 Env proteins with a single mutation (770E, 772E, or 788E) were reduced in fusogenicity by about 20−50% compared to parental Env, while Env proteins with double mutations (770E/788E and 772E/788E) were reduced in fusogenicity by more than 70% compared to the parental Env fusogenic activity, suggesting an additive effect of the LLP-2 point mutations. In contrast to the reduction in fusogenicity observed with the individual 770E and 772E LLP-2 mutations in ME46 Env, the individual 770E and 772E mutations in the 89.6 LLP-2 region failed to decrease the fusogenicity of the 89.6 Env in the standard assay (Fig. 4B). The 89.6 Env with the 788E mutation was about 50% reduced in fusogenic activity relative to the parental Env, but the addition of the 770E mutation did not further decrease Env fusogenicity, the latter being in contrast to the additive effect observed with the ME46 Env with the same mutations. The 89.6 Env with the 772E/788E mutations was similar to the homologous ME46 mutant Env in that both were reduced by about 70% in fusogenic activity compared to their respective parental Env. These fusogenicity assays, in agreement with the previous single cycle infectivity assays, demonstrated the role of LLP-2 as a determinant of Env fusogenicity, but highlight the potential for differential effects on this Env property caused by identical mutations in the two Env species.

Figure 4. Cell-to-cell fusion mediated by parental and mutant envelope proteins.

The env sequence was cloned from proviral DNA from each of the viruses into the mammalian expression vector pTR600 (Ross et al., 2000; Ross et al., 2001). Cell-to-cell HIV Env mediated fusion was performed and assayed as described in Materials and Methods and elsewhere (Edwards et al., 2002; Rucker et al., 1997). A). Relative cell-to-cell Env mediated fusogenicity of ME46 Envs bearing the indicated mutations compared to the parental Env protein. B) The ability of 89.6 Envs containing the indicated mutation to promote cell-to-cell fusion relative to the 89.6 parental envelope. The data is a result of an average of 3 to 6 independent experiments each done in quadruplicate, and the error bars represent the SEM.

Env incorporation into virus particles and total Env expression from cellular lysate.

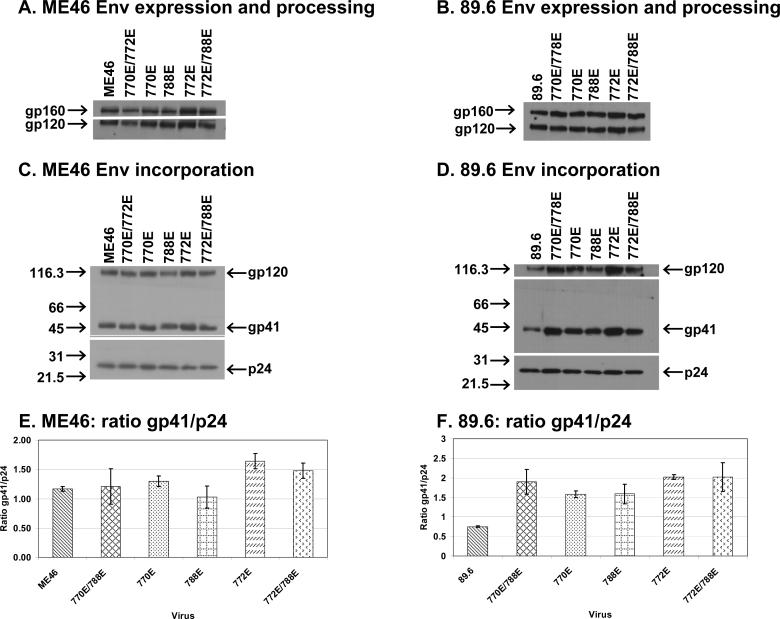

Previous studies from our lab with ME46 viruses indicated that the double point mutation in LLP-1 resulted in a defect in Env incorporation into virus particles, while the double point mutation in LLP-2 did not affect Env incorporation (Kalia et al., 2003). In agreement with the prior report with the ME46 LLP-1 mutant virus (Kalia et al., 2003), an 89.6 mutant virus with the 846E and 848E modifications showed a nearly 8-fold decrease in Env incorporation compared to the parental virus (data not shown). In light of observed alteration in viral infectivity and replication properties observed with various LLP-2 mutants, we sought to determine the effects of the various mutations on the LLP-2 mutant Env expression in cells (Figs. 5A and 5B) and incorporation into viral particles (Figs. 5C and 5D). Mutant proviral clones containing the various LLP mutations were transfected into 293T cells, and the cellular lysates and supernatants from the same transfection were assayed by immunoblots for Env expression or incorporation, respectively. The data presented in Figure 5 demonstrated that the LLP-2 mutations in ME46 Env did not substantially affect either the levels of Env expression (Fig. 5A) or incorporation into virus particles compared to the parental virus (Fig. 5B). Densitometry analysis of blots from two to three independent experiments indicated a less than 1.5 fold increase in Env incorporation for ME46 772E mutant viruses, as calculated from average gp41/p24 ratios (Fig. 5E). As observed with LLP-2 mutants in ME46, the LLP-2 mutations in 89.6 did not substantially affect the levels of Env expression (Fig. 5C). However, the various LLP-2 mutations in 89.6 Env all resulted in an apparent increase in the levels of Env incorporation with the 89.6 viruses (Fig 5D). Based on the densitometry results of blots from 2−3 independent experiments, the ratio of gp41 to p24 was increased approximately 2 to 3-fold (Fig. 5F) in the 89.6 LLP-2 mutants compared to the parental 89.6 virus.

Figure 5. Envelope expression and processing, incorporation into virus particles, and densitometry analysis of Env incorporation.

The data in this figure shows the levels of envelope expression, processing, and incorporation among the ME46 and 89.6 mutant and parental viruses. 293T cells were transfected with proviral DNA, and the cell lysates and supernatants were harvested and processed for expression and incorporation analyses, respectively as described in Materials and Methods. Panels A and B show the level of Env expression and processing from the ME46 or 89.6 proviral constructs, respectively, while panels C and D display the levels of Env incorporation from the same transfection shown in panels B and C. Numbers to the left of each film in panels C and D represent the mass in kilodaltons (KD) while the viral proteins are identified on the right. The blots shown are representative of two to three independent transfections. For the graphs shown in panels E and F, x-ray films from two to three independent transfections were subjected to densitometry using a Bio-Rad Gel Doc™ 2000 imagining system, and the amount of gp41 and p24 was determined for the mutants and the parental virus using Quality One 1D analysis software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The ratio of gp41 to p24 was then determined for the ME46 and 89.6 viruses in panels E and F, respectively. The error bars represent the standard deviations.

Discussion

We and others have previously demonstrated by the introduction of point mutations or deletion of short stretches of amino acids that the LLP-1 and LLP-2 domains perform critical, but distinct roles in HIV Env incorporation, replication kinetics, infectivity, and/or fusogenicity (Kalia et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2002; Murakami and Freed, 2000a; Piller et al., 2000). However, these studies have all focused on the effects of LLP mutations in the context of one particular strain of HIV. Since it has been demonstrated that observed phenotypes conferred by mutations within the ICD can be cell-type dependent (Akari et al., 2000; Dubay et al., 1992; Gabuzda et al., 1992; Lambele et al., 2007; Murakami and Freed, 2000b; Piller et al., 2000), the current study was to designed to determine whether or not homologous mutations within the LLP regions of two different strains of HIV would confer similar phenotypes. A summary of these results is provided in Table 1. The data indicate that the specific point mutations within the LLP-1 were consistent in both viral strains in producing a defective Env phenotype that suppressed Env incorporation into virions resulting in noninfectious and replication defective particles. In contrast, the mutations in the LLP-2 domain were found to produce diverse effects in the phenotypes of the two strains of HIV, as related to Env incorporation, fusogenicity, and infectivity.

Table 1.

Summary of the effects of LLP mutations on viral phenotypes relative to the parental virus

| Infectivitya | Replication in CEMX174b | Replication in PBMCc | Fusione | Env Contentg | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation | ME46 | 89.6 | ME46 | 89.6 | ME46 | 89.6 | ME46 | 89.6 | ME46 | 89.6 |

| 846E/848E | ↓ | ↓ | ↓↓ | - | ↓↓d | - | NDf | ND | ↓h | ↓ |

| 770E | ↓ | ↑↑ | = | = | = | = | ↓ | = | = | ↑↑ |

| 772E | = | ↓ | = | ↓ | = | = | ↓ | = | ↑ | ↑↑ |

| 788E | ↓ | ↓ | = | ↓ | = | = | = | ↓ | = | ↑↑ |

| 770E/788E | ↓ | ↑↑ | = | ↓ | = | = | ↓ | ↓ | = | ↑↑ |

| 772E/788E | ↓ | = | = | ↓↓ | = | = | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑↑ |

Infectivity as determined in TZM-bl cells (Fig. 2): “↓” indicates > 40% reduction relative to parental virus. “=” means infectivity was within 30% of parental virus. “↑↑” indicates > 100% increase in infectivity.

Replication kinetics in CEMX174 cells and PMBC, respectively (Fig. 3). “−” sign indicates no detectable levels of p24 in the supernatant. “↓↓” shows > 10 fold reduction in replication kinetics. “↓” designates delayed or > two-fold reduction in replication activity. “=” signifies mutant viruses within 2 fold in the level of replication relative of the parental virus.

Replication kinetics in CEMX174 cells and PMBC, respectively (Fig. 3). “−” sign indicates no detectable levels of p24 in the supernatant. “↓↓” shows > 10 fold reduction in replication kinetics. “↓” designates delayed or > two-fold reduction in replication activity. “=” signifies mutant viruses within 2 fold in the level of replication relative of the parental virus.

Data from Kalia et al, 2003.

Cell-to-cell fusion mediated by mutant Env proteins (Fig 4). “=” indicates mutant Env proteins within 20% the fusion activity of the parental Env. “↓” signifies a decrease in fusion.

ND= not determined.

The Env incorporation of the mutant LLP viruses (Figs. 5 and 6). “−” indicates a decrease in Env incorporation. “=” signifies equivalent Env incorporation levels. “↑” designates mutant viruses with an increase in Env content. “↑↑” signifies a > two-fold increase.

Data from Kalia et al, 2003.

With both the ME46 and 89.6 strains of HIV-1, the combination of the 846E and 848E mutations in LLP-1 had a profound effect on viral infectivity and replication, apparently correlating with the observed reduction of Env incorporation into progeny virions (Kalia et al., 2003, Table 1). These two targeted arginine residues within the LLP-1 region are highly conserved, and the LLP-1 region shares sequence similarity with other lentiviruses such as SIV and EIAV (Miller et al., 1993; Tencza et al., 1997). This high degree of conservation in LLP-1 suggests critical functions in HIV-1 replication. Piller et al. (2002) introduced charged substitutions at positions 841 and 848 (RR/EE) into the NL4.3 strain of HIV-1. The mutant virus produced from transfected 293T cells displayed about a 50% reduction in Env incorporation, a 10-fold reduction in replication activity in CEMX174 cells at the early time points, and about a 5-fold reduction at the peak of viral replication relative to the parental virus. In another study, Lee et al. (2002) demonstrated that deletion or substitution of certain individual residues within the LLP-1 domain could have an effect on Env steady state expression, incorporation, or infectivity depending on the specific mutation. Deletion of the last 12 residues of the LLP-1 region has also been shown to reduce infectivity, and other studies have indicated that these residues are important for the transport of Env from the endoplasmic reticulum and the overall association of this region with cellular membranes, indicating an important function of LLP-1 for virus-host cell interactions and Env transport (Chen et al., 2001; Yu et al., 1993). Thus, these various studies consistently indicate an important role for LLP-1 in Env function, and further studies are certainly indicated to elucidate the mechanisms and cell interactions by which LLP-1 contributes to HIV-1 infection and replication.

In contrast to our results with the LLP-1 mutations, the LLP-2 mutations resulted in strain specific phenotypic effects on ME46 and 89.6. With regard to infectivity in the TZM-bl cell line, homologous glutamic acid substitutions that conferred an increase or decrease in infectivity in one virus did not necessarily have the same effect in the other virus, highlighting the importance of the specific Env species in modulating LLP-2 effects on function. In particular, 89.6 viruses with either the 770E mutation alone or a combination of both the 770E and 788E mutations had a greatly increased level of infectivity compared to the parental virus, while these same modifications in ME46 resulted in an additive decrease in infectivity (Fig. 2, Table 1). Interestingly, the increase in infectivity observed with the 89.6 LLP-2 mutants did not correlate with an evident increase in replication levels in CEMX174 cells or in human PBMC (Fig. 3B, 3D, and Table 1). Taken together, these observations demonstrate the potential for strain-specific and cell-specific effects of specific LLP-2 mutations, presumably reflecting differences in the effects of overall Env sequences on the structure and functional interactions of the envelope complex with cellular proteins.

We previously reported that an ME46 Env with both 770E and 788E mutations was defective in the ability to promote cell-to-cell fusion despite wild type expression levels of Env on the cell surface (Kalia et al., 2003). However, the effects of individual mutations on Env fusogenicity were not examined. In the present study, we were able not only to characterize the effect of the double LLP-2 mutation on 89.6 Env fusogenicity, but also to analyze the relative contributions of the individual point mutations to changes in fusogenicity for two Env species. The results of these studies indicated that the double LLP-2 mutations also affected the ability of the 89.6 Env to promote cell-to-cell fusion (Fig. 4, Table 1). In the case of the ME46 Env, the single 770E mutation apparently contributed more to the fusion defect than the 788E mutation alone; the opposite pattern of single mutation effects on fusogenicity was evident for the 89.6 Env (Fig. 4). Additionally, Env proteins containing the 772E and 788E mutations were fusion defective, and again, the 788E mutation contributed more to this phenotype with the 89.6 Env than the 772E mutation alone. Both sets of observations highlight the importance of the Env variant specificity in determining the role of LLP-2 in fusion phenotypes. Other recent studies have also indicated the importance of the LLP-2 sequence in the fusion process. For example, Wyss et al (2005) reported that Env proteins that retained the first four amino acids of LLP-2 were normal for cell-to-cell fusion, but further deletion increased fusion activity, presumably due to major conformational changes in Env that exposed the CD4 binding site and increasing the fusion potential of Env. In a previous study, we showed that the 770E and 788E mutations together did not increase exposure of either the CD4 or the co-receptor binding sites (Kalia et al., 2005).

A prior report with ME46 indicated that the combination of the 770E and 788E mutations did not alter the Env content in virus particles or alter Env expression and processing (Kalia et al., 2003), thus it was not surprising that these phenotypes were not altered with viruses that possessed only one of these mutations (Figs. 5A, 5C, 5E, and Table 1). The only mutant ME46 viruses that showed a modest increase in Env incorporation were those bearing the 772E mutation. In contrast, all of the LLP-2 89.6 mutants had at least a 2 to 3-fold increase in the levels of Env incorporation (Figs. 5B, 6B, and Table 1). This increased incorporation could not be attributed to increased expression or processing (Fig 5D), so it is likely that the increased Env incorporation occurs at some point during the assembly process. Interestingly, increased levels of Env incorporation did not necessarily increase other Env-related functions, such as infectivity or replication kinetics. These findings with the 89.6 LLP-2 mutants are in contrast to reports with SIV where changes in the ICD, even small deletions within LLP-2, can increase SIV Env incorporation that can be correlated to increases in other Env-related phenotypes (Celma et al., 2001; Manrique et al., 2001; Yuste et al., 2005; Yuste et al., 2004; Zingler and Littman, 1993). While it is not known what the causes are for this difference, it is possible that the Env content of the LLP-2 89.6 mutant viruses is altered (i.e., reduced) during replication in permissive cells such as CEMX174. Previous studies have shown that the Env content of HIV virus particles can be altered in different cell types (Akari et al., 2000; Murakami and Freed, 2000b; Piller et al., 2000). Additionally, with a few exceptions, many of the prior reports utilized truncated forms of the Env protein. The results of this study clearly indicate that even single point mutations within the LLP-2 region can alter Env incorporation, but the strain specificity of this phenotype once again highlights the strain dependence on the exact phenotypic alterations.

While the results of these and previous studies convincingly establish a role for the ICD as a critical determinant of Env conformation and function, the mechanisms by which the ICD sequences, including LLP-1 and LLP-2, affect Env structural and functional properties remain speculative at this time. Various studies have demonstrated the importance of potential endocytic motifs in the ICD as determinants of Env trafficking and surface localization in infected or transfected cells (Boge et al., 1998; Egan et al., 1996; Ohno et al., 1997; Rowell et al., 1995; Wyss et al., 2001; Ye et al., 2004). Moreover, recent studies by others have revealed a critical role for ICD-Gag interactions as a regulator of Env fusogenicity (Murakami et al., 2004; Wyma et al., 2004). We have previously proposed that that HIV-1 gp41 sequences including the membrane-proximal tryptophan-rich domain, the membrane spanning domain, and the ICD cooperatively facilitate Env association with the cellular and viral lipid bilayers and that this series of helical peptide-membrane interactions is a major determinant of Env fusogenicity, presumably via alterations in ectodomain conformations (Kalia et al., 2003; Kalia et al., 2005). Assuming the currently accepted model that the ICD sequences are indeed all localized to the interior surface of the lipid bilayer, the effects of LLP mutations on Env functional properties would then be attributed to allosteric effects on Env ectodomain conformation caused by changes in the extent or stability of ICD-lipid bilayer interactions. In this regard, we have previously shown that amino acid changes in LLP sequences that reduce the characteristic positively charged amphipathic potential of these peptide segments markedly reduce membrane interactions (Miller et al., 1993; Tencza et al., 1995). The differential effects of identical LLP-2 point mutations on the phenotypes of variant Envs may then be explained by the influence of different Env sequences in determining the extent of alterations in ICD-membrane interactions and resulting changes in Env conformation caused by specific ICD mutations. The role of membrane interactive peptide segments in modulating Env structure and function is similar that proposed for integrin protein signaling in which conformational alterations in response to extracellular or intracellular stimuli are produced by cooperative allosteric interactions between ecto- and cytoplasmic domains (Hynes, 2002).

It should be noted, however, that the model described above for HIV-1 Env structure is based on the assumption that the gp41 protein contains a single membrane spanning domain and that ICD sequences are indeed exclusively located on the interior side of the lipid bilayer. While this membrane topology is widely accepted, there are experimental data that indicate that segments of the ICD may actually be located on the exterior of the lipid bilayer. In early studies of Env neutralization determinants, Kennedy and colleagues first reported that rabbit antiserum made against a specific ICD synthetic peptide (“Kennedy epitope”) located between the putative membrane spanning domain and LLP-2 segments effectively neutralized infectious HIV-1 (Chanh et al., 1986; Kennedy et al., 1986). More recently, Dimmock and colleagues have published a series of studies that demonstrate that peptide-specific antisera targeted to the Kennedy neutralization epitope sequences are reactive with HIV-1 Env expressed on the surface of cells or virus particles (Cheung et al., 2005; Cleveland et al., 2003; Reading et al., 2003). Based on these observations, these investigators have proposed an alternative model for gp41 membrane topology that involves two additional membrane spanning domains in the putative ICD preceding LLP-2 in an arrangement that positions the Kennedy epitope on the exterior of the lipid bilayer and the various LLP segments on the interior surface of lipid bilayer (Hollier and Dimmock, 2005). These investigators further suggest that gp41 may actually be in a dynamic flux between the single or triple membrane spanning domain structures. While further experiments are clearly needed to definitively define the membrane topology of the ICD sequences of gp41, it is interesting to note that both models predict an exclusively internal location of the three different LLP segments and thus are compatible with our model of the allosteric effects of LLP on Env structure and function, as described above.

Materials and Methods

Cells, proviral constructs, expression plasmids, antibodies, and other reagents.

Mammalian 293T (from M. Calos, University of Stanford through T. Reinhart, University of Pittsburgh) and quail QT6 (a kind gift from R.W. Doms, University of Pennsylvania, through K. Stefano Cole, University of Pittsburgh) cells were maintained in DMEM (Cambrex Bio Science Walkersville Inc., Walkersville, MD) containing 10% fetal calf serum (FBS, Gemini Bio-Products, Woodland, CA) and 2 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA). The TZM-bl indicator cell line (Derdeyn et al., 2000; Wei et al., 2002), which was obtained from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, was maintained in the same manner as above with the addition of 100 units/ml penicillin G and 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate (pen/strep, Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA). CEMX174 cells (Salter et al., 1985) from the NIH AIDS Research Reagent Program were grown in RPMI media (Cambrex Bio Science Walkersville Inc., Walkersville, MD) supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, and pen/strep. Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from the buffy coat of fresh human blood by Histoplaque-1077 (Sigma Diagnostics, Inc, St. Louis, MO) density gradient centrifugation. The resulting PBMC were maintained in the same media as CEMX174 cells with the addition of 20% FBS and the M-form of phytohemagglutin (PHA, Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) at a starting concentration of 1−106 cells/ml for 2−3 days prior to infection. The HIV 89.6 full-length proviral construct (Collman et al., 1992) was obtained from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, and the construction of the ME46 full-length proviral DNA clone was described previously (Kalia et al., 2003). The pTR600 expression plasmid, used to express the viral Env proteins under control of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter, is a patented expression vector that was kindly provided by T.M. Ross (University of Pittsburgh) (Ross et al., 2000; Ross et al., 2001). Plasmid vectors used for the cell-to-cell fusion assay that express human CD4 receptor, CXCR4 chemokine co-receptor, and the firefly luciferase protein were also provided as a kind gift from R.W. Doms through K. Stefano Cole, and their construction is described elsewhere (Rucker et al., 1997). The recombinant vaccinia virus, vTF1.1 (Alexander et al., 1992), also used for the cell-to-cell fusion assay was provided by K. Stefano Cole. Monoclonal antibodies 2F5 (Buchacher et al., 1994; Purtscher et al., 1996; Purtscher et al., 1994) and AG 3.0 (Simm et al., 1995) used to detect the gp41 and p24 viral proteins, respectively, on immumo-blots, were acquired from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program.

PCR Mutagenesis and Cloning.

The construction of mutant ME46 proviral DNA constructs bearing the 770E and 788E (ME46 MX2) or the 846E and 848E (ME46 MX1) mutations are described elsewhere (Kalia et al., 2003). In the current study, point mutations were introduced into the LLP-1 and LLP-2 regions (Fig. 1 and Table 2) using a modified overlap PCR mutagenesis protocol briefly described elsewhere (Moeller et al., 2001). The nucleotide sequences of the primers used for the PCR mutagenesis are listed in Table 2. The Herculase Enhanced Polymerase Blend (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) was used for all PCR amplifications, and all restriction enzymes used for cloning are from New England Biolabs, Inc (Beverly, MA). For the construction of the additional ME46 mutant proviral constructs, the full-length proviral parental DNA was used as the template for PCR amplification. In the first step of the overlapping PCR mutagenesis, template DNA was combined with the 3′ non-mutagenic primer (ME46−3′, Table 2) and one of the sense mutagenic primers (ME46−770E, ME46−772E, or ME46−788E, Table 2) in one reaction, while in a separate reaction, the 5′ non-mutagenic primer (ME46−5′, Table 2) was combined with one of the anti-sense mutagenic primers (sequences not shown). The resulting PCR amplification products were purified using the Qiagen Gel Extraction kit (Qiagen Sciences, Germantown, MD) and were used as templates for the second step of the overlap PCR mutagenesis. After 11 amplification cycles, the reaction was paused, both non-mutagenic primers (ME46−3′ and ME46−5′, Table 2) were added, and the PCR amplification was allowed to continue for an additional 26 cycles. The PCR products from the second step of the PCR mutagenesis were cloned back into the full-length parental DNA using Mfe I and Xho I restriction sites that are unique within the ME46 construct. The ME46 proviral mutant construct with the 772E mutation was used as a template for PCR mutagenesis to generate the mutant containing both the 772E and 788E mutations. All of the resulting clones were then sequenced for the entirety of the region that was PCR amplified by using a Perkin Elmer ABI 3100 sequencer (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom) to confirm that the clones did not contain any additional missense mutations that might have been introduced during the PCR amplification. For the construction of the 89.6 proviral mutants, a subgenomic clone was made by digestion of the full-length proviral DNA with Eco RI and Sph I. This DNA fragment was inserted into the pUC19 cloning vector (New England Biolabs Inc., Beverly, MA) and was used as a template for the same PCR mutagenesis strategy described above to generate sub-genomic clones containing one or more of the mutations. These sub-genomic clones were verified by sequencing the region that was PCR amplified. The clones were digested with Eco RI and Sph I, and the resulting fragments containing the viral sequences were individually cloned back into the full-length proviral DNA 89.6 parental clone digested with the same enzymes. All of the full-length 89.6 proviral mutant clones were verified by sequencing to ensure they still had the intended mutation. For the generation of the Env expression plasmids used for the cell-to-cell fusion assay, the proviral DNAs were used as templates to PCR amplify the env sequence using primers containing Bam HI and Hind III restriction sites for directional cloning into the pTR600 expression vector (Ross et al., 2000; Ross et al., 2001).

Table 2.

Nucleotide sequence of PCR primers used to introduce mutations

| Primer name | Sequence 5′ → 3′ | Nucleotide positionsa |

|---|---|---|

| ME46−3′b | GTTATTGGTCTTAAAGGTACCTGAGGTCTGACTG | 9035−9002 |

| ME46−5′c | CAATATCGAGATCTTCAGACCTGGTGGAGGAGAT | 7610−7646 |

| ME46−770Ed | CTCTTCAGCTACCACGAATTGAGAGACTTACTC | 8517−8549 |

| ME46−772E | AGCTACCACCGCTTGGAAGACTTACTCTTGATTG | 8523−8556 |

| ME46−788E | GAACTTCTGGGACGCGAGGGGTGGGAAATCCTC | 8571−8603 |

| 89.6−3′e | CAGACGGGCACACACTACTTGAAGCACTCA | 9655−9626 |

| 89.6−5′f | GGCACTGAAGGAAATGACATAATCACACTC | 7443−7472 |

| 89.6−770E | CTCTTCCTCTACCACGAATTGAGAAACTTACTC | 8517−8549 |

| 89.6−772E | TCTTCCTCTACCACCTCTTGGAAAACTTACTCTTGATTGTA | 8518−8558 |

| 89.6−788E | GAACTTCTGGGACGCGAGGGGTGGGAAGCCCTCAAATATTGG | 8571−8612 |

| 89.6−846E | CTATTCGCAACATACCTACAGAGATCAGACAGGGCTTGGAAAG | 8740−8782 |

| 89.6−848E | GCAACATACCTACAGAGATCGAGCAGGGCTTGGAAAGGGCTTT | 8746−8788 |

Relavant segments of the HIV-1 ME46 and HIV-1 89.6 env gene DNA sequences were entered into the HIV/SIV Sequence Locator Tool at the Los Alamos Sequence Database to give the nucleotide positions relative to HXB2.

ME46−3′ and ME46−5′ represent the non-mutagenic primers used in the overlap PCR mutagenesis protocol.

ME46−3′ and ME46−5′ represent the non-mutagenic primers used in the overlap PCR mutagenesis protocol.

This table lists the sense strand mutagenic primer to pair with the 3′ non-mutagenic primer for the first step of the overlap PCR mutagenesis in one reaction. An appropriate corresponding antisense primer to pair with the 5′ non-mutagenic primer was also used (sequence not shown) in a parallel reaction. The sequences in bold represent the codon changed to introduce the glutamic acid residue mutation.

89.6−3′ and 89.6−5′ represent the non-mutagenic primers used in the overlap PCR mutagenesis protocol.

89.6−3′ and 89.6−5′ represent the non-mutagenic primers used in the overlap PCR mutagenesis protocol.

Production of virus from proviral DNA.

Viral Stocks of ME46, 89.6, and the mutant derivatives were generated by transfecting 293T cells with the appropriate DNA construct using the Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA). Briefly, two to three days prior to transfection, T-75 cm2 flasks (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) were seeded with 3−106 cells. Prior to transfection, the 89.6 constructs were digested with either Sph I or Fsp I, and the ME46 constructs were digested with NgoM IV. At 70−80% confluency, the 293T cells were transfected with one of the digested DNA constructs and Lipofectamine 2000 in the presence of Optimem®I with GlutaMax™-I medium (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol using a ratio of 1.7:1 Lipofectamine 2000 to DNA. At two days post-transfection, viral supernatants were harvested and passed though 0.45 μm pore Millex Durapore® membrane filters (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The amount of virus produced from transfected cells was determined by measuring p24 antigen present in the supernatant using a p24 ELISA kit per the manufacturer's protocol (DuPont, Wilmington, DE).

Infectivity assays using TZM-bl indicator cells.

The single cycle infectivity of each of the mutant viruses relative to the parental virus was determined in a single cycle using TZM-bl indicator cells (Derdeyn et al., 2000; Wei et al., 2002). One day prior to infection, TZM-bl cells were seeded in 96-well tissue culture plates (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) at a concentration of 25,000−50,000 cells per well. The following day, the culture media was removed, and filtered supernatants from transfected 293T cells were used to infect the cells in quadruplicate after p24 level normalization. After two hours of incubation at 37°C, the infected wells were brought to 200 μl in volume with DMEM containing 10% FBS, 2mM L-glutamine, and pen/strep. The cells were then washed 1X in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) 48 h after incubation at 37°C, and β-galactosidase activity was measured using the Beta-Glo™ Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI) by lysis of the cells with the Beta-Glo™ Assay Substrate (Promega, Madison, WI). Following a 1 hr incubation at room temperature, the lysed cells were transferred to a 96-well white assay plate (Corning Inc., Corning, NY), and light intensity units (LIU) per well was measured using a Veritas microplate luminometer (Turner Biosystems, Sunnyvale, CA). An average LIU was determined for each virus, and the average LIU of the mutant viruses was compared to the appropriate parental virus. Each virus was tested within each assay relative to the parental virus in three to four independent experiments, and the standard error of measurement (SEM) was determined for each mutant virus.

Viral Replication Kinetics.

The replication kinetics of each mutant derivative virus was compared to the parental virus in both the CEMX174 cell line and in human PBMC. For kinetics in CEMX174 cells, cell-free filtered supernatants from transfected 293T cells were normalized to p24 levels (20 ng/ml) and used to infect 5×106 cells with 1 ml of virus for 1.5 h at 37°C. The cells were then washed and cultured in RPMI containing 10% FBS, 2mM L-glutamine, and pen/strep. At 1−3 day intervals, an aliquot of the supernatant from each flask was removed prior to any media changes to measure the amount of p24 antigen produced as described above. After day 6, at 3−4 day intervals, half of the cell culture and/or half of the cells were removed and replaced with fresh medium. The kinetics of viral replication in human PBMC was determined by the infection of 1−107 PHA stimulated polybrene treated cells with 1 ml of cell-free filtered virus from transfected 293T cells after p24 normalization (40 ng/ml). After incubation for 1.5 h at 37°C, the cells were washed twice with RPMI containing 20% FBS, 2mM L-glutamine, and pen/strep. The infected cells were then resuspended at a concentration of 1−106 cells/ml per T-25 tissue culture flask with the culture media mentioned above plus 10 units/ml of human IL-2 (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). At intervals of 2−3 days, supernatant was removed prior to any media changes to determine the level of p24 antigen production. On days 3 and 10, one half of the culture media was replaced with fresh media, and on day 7, half of the culture was replaced with fresh media containing 5−106 PHA-stimulated PMBC.

Cell-to-cell fusion assay.

A quantitative cell-to-cell fusion assay based on luciferase activity was adapted from protocols described previously (Edwards et al., 2002; Rucker et al., 1997). One day prior to transfection, 293T cells were seeded at a concentration of 1−106 cells per well in 6-well plates (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA), and quail QT6 cells were plated at a concentration of 1−105 cells per well in 24 well plates (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA). The following day, the 293T cells were transfected as described above with one of the Env expression plasmids using a Lipofectamine 2000 to DNA ratio of 1.7:1. In parallel, QT6 (target) cells were transfected with CXCR4 and CD4 expression plasmids under control of the CMV promoter and a luciferase expression plasmid directed by the T7 promoter (Rucker et al., 1997). After 4 to 6 h, the transfection mixture was removed and replaced with DMEM containing 10% FBS and 2mM L-glutamine. One day following transfection, the Env expressing 293T (effector) cells were infected with a vaccinia virus expressing T7 polymerase (Alexander et al., 1992) at a multiplicity of infection of 10 in DMEM containing 2.5% FBS. After 1 hr of incubation at 37°C, the infection medium was removed and replaced with DMEM containing 10% FBS, 2mM L-glutamine, and 100 μg/ml rifampicin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The next day, the effector cells were mixed with the target cells in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 μg/ml rifampicin, and 10mM cytosine arabinoside (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The effector and target cells were allowed to fuse overnight, and the cells were lysed with reporter lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, WI). Luciferase activity was measured with the Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI), and LIU were measured using a Veritas microplate luminometer (Turner Biosystems, Sunnyvale, CA). Relative fusogenicity was determined by comparing the LIU of each mutant envelope to the parental envelope, and the resulting data is an average of 3 to 6 independent experiments done in quadruplicate.

Viral protein analysis.

To determine the levels of viral envelope incorporation into virus particles, 293T cells in 6-well plates were transfected as described above for the production of virus from proviral DNA. Two to three days following the transfection, viral supernatants were harvested, filtered, and measured for p24 levels as described above. Similar amounts of virus based on the p24 ELISA of viral supernatants were centrifuged to pellet the virus, and the resulting pellet was resuspended in PBS for sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis using 4−12% Bis-Tris NuPAGE® gels with an XCell SureLock™ Mini-cell apparatus and 1X MOPS buffer (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Following electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred to polyvinylidine difluoride (PVDF, Millipore, Billerica, MA) membranes using a Mini Trans-Blot® cell (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Protein bands were visualized by using the SuperSignal® West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) after probing the appropriate area of the membrane with rabbit polyclonal anti-gp120 (1:1000 dilution, Advanced Biotechnologies Incorporated, Columbia, MD), human anti-gp41 (2F5, 1:500 dilution), and mouse anti-p24 (AG 3.0, 1:250 dilution) as primary antibodies followed by an appropriate secondary antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The blots were exposed to Kodak X-OMAT LS x-ray film (Eastman Kodak Company, Rochester, NY), and the levels of gp41 and p24 proteins were measured from the x-ray film using a Bio-Rad Gel Doc™ 2000 imaging system and Quality One analysis software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). For envelope expression and processing, cells from the same experiment as the harvested viral supernatant were lysed with 1X MOPS running buffer (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA), subjected to one freeze-thaw cycle, briefly sonicated with a Misonix Sonicator® 3000 (Misonix, Farmingdale, NY), and subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis and transfer to a PVDF membrane as described above. Viral proteins gp120 and gp160 were visualized as described above with the rabbit polyclonal anti-gp120 antibody as a primary antibody followed by an appropriate secondary antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Acknowledgements

We thank the following individuals for providing us with valuable reagents used in this study as described in the Materials and Methods: Drs. Kelly Stefano Cole, Todd Reinhart, and Ted Ross (University of Pittsburgh) and Dr. Michele Calos (University of Stanford). Additionally, we would like to thank Deena M. Ratner for assistance with the TZM-bl assay, Mary White for the p24 assays, Jessica Hughes for assistance with the Gel Doc™ 2000 apparatus, and Dr. Tim Mietzner for helpful comments regarding this manuscript. The following reagents were obtained through the NIH AIDS Research and Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: HIV-1 gp41 monoclonal antibody 2F5, from Dr. Hermann Katinger, monoclonal antibody to HIV-1 p24 (AG3.0) from Dr. Jonathan Allan, CEMX174 from Dr. Peter Cresswell, TZM-bl from Dr. John C. Kappes, Dr. Xiaoyun Wu and Tranzyme Inc, and p89.6 from Dr. Ronald G. Collman. This research was supported by the following grants from the NIH: R21 AI070033, T32 AI049820.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Affranchino JL, Gonzalez SA. Mutations at the C-terminus of the simian immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein affect gp120-gp41 stability on virions. Virology. 2006;347:217–25. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akari H, Fukumori T, Adachi A. Cell-dependent requirement of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 cytoplasmic tail for Env incorporation into virions. J. Virol. 2000;74:4891–3. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.10.4891-4893.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander WA, Moss B, Fuerst TR. Regulated expression of foreign genes in vaccinia virus under the control of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase and the Escherichia coli lac repressor. J. Virol. 1992;66:2934–42. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.5.2934-2942.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blot G, Janvier K, Le Panse S, Benarous R, Berlioz-Torrent C. Targeting of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope to the trans-Golgi network through binding to TIP47 is required for env incorporation into virions and infectivity. J. Virol. 2003;77:6931–45. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.12.6931-6945.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boge M, Wyss S, Bonifacino JS, Thali M. A membrane-proximal tyrosine-based signal mediates internalization of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein via interaction with the AP-2 clathrin adaptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:15773–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchacher A, Predl R, Strutzenberger K, Steinfellner W, Trkola A, Purtscher M, Gruber G, Tauer C, Steindl F, Jungbauer A, et al. Generation of human monoclonal antibodies against HIV-1 proteins; electrofusion and Epstein-Barr virus transformation for peripheral blood lymphocyte immortalization. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1994;10:359–69. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bultmann A, Muranyi W, Seed B, Haas J. Identification of two sequences in the cytoplasmic tail of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein that inhibit cell surface expression. J. Virol. 2001;75:5263–76. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.11.5263-5276.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celma CC, Manrique JM, Affranchino JL, Hunter E, Gonzalez SA. Domains in the simian immunodeficiency virus gp41 cytoplasmic tail required for envelope incorporation into particles. Virology. 2001;283:253–61. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.0869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti L, Emerman M, Tiollais P, Sonigo P. The cytoplasmic domain of simian immunodeficiency virus transmembrane protein modulates infectivity. J. Virol. 1989;63:4395–403. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.10.4395-4403.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan DC, Fass D, Berger JM, Kim PS. Core structure of gp41 from the HIV envelope glycoprotein. Cell. 1997;89:263–73. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80205-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan WE, Chen SS. Downregulation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag expression by a gp41 cytoplasmic domain fusion protein. Virology. 2006;348:418–29. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanh TC, Dreesman GR, Kanda P, Linette GP, Sparrow JT, Ho DD, Kennedy RC. Induction of anti-HIV neutralizing antibodies by synthetic peptides. EMBO J. 1986;5:3065–71. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04607.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Singh MK, Balachandran R, Gupta P. Isolation and characterization of two divergent infectious molecular clones of HIV type 1 longitudinally obtained from a seropositive patient by a progressive amplification procedure. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1997;13:743–50. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SS, Lee SF, Wang CT. Cellular membrane-binding ability of the C-terminal cytoplasmic domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope transmembrane protein gp41. J. Virol. 2001;75:9925–38. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.20.9925-9938.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung L, McLain L, Hollier MJ, Reading SA, Dimmock NJ. Part of the C-terminal tail of the envelope gp41 transmembrane glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is exposed on the surface of infected cells and is involved in virus-mediated cell fusion. J. Gen. Virol. 2005;86:131–8. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80439-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland SM, McLain L, Cheung L, Jones TD, Hollier M, Dimmock NJ. A region of the C-terminal tail of the gp41 envelope glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 contains a neutralizing epitope: evidence for its exposure on the surface of the virion. J. Gen. Virol. 2003;84:591–602. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18630-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collman R, Balliet JW, Gregory SA, Friedman H, Kolson DL, Nathanson N, Srinivasan A. An infectious molecular clone of an unusual macrophage-tropic and highly cytopathic strain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 1992;66:7517–21. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.7517-7521.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosson P. Direct interaction between the envelope and matrix proteins of HIV-1. EMBO J. 1996;15:5783–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day JR, Munk C, Guatelli JC. The membrane-proximal tyrosine-based sorting signal of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 is required for optimal viral infectivity. J. Virol. 2004;78:1069–79. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.3.1069-1079.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derdeyn CA, Decker JM, Sfakianos JN, Wu X, O'Brien WA, Ratner L, Kappes JC, Shaw GM, Hunter E. Sensitivity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to the fusion inhibitor T-20 is modulated by coreceptor specificity defined by the V3 loop of gp120. J. Virol. 2000;74:8358–67. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.18.8358-8367.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doranz BJ, Rucker J, Yi Y, Smyth RJ, Samson M, Peiper SC, Parmentier M, Collman RG, Doms RW. A dual-tropic primary HIV-1 isolate that uses fusin and the beta-chemokine receptors CKR-5, CKR-3, and CKR-2b as fusion cofactors. Cell. 1996;85:1149–58. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubay JW, Roberts SJ, Hahn BH, Hunter E. Truncation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane glycoprotein cytoplasmic domain blocks virus infectivity. J. Virol. 1992;66:6616–25. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6616-6625.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards TG, Hoffman TL, Baribaud F, Wyss S, LaBranche CC, Romano J, Adkinson J, Sharron M, Hoxie JA, Doms RW. Relationships between CD4 independence, neutralization sensitivity, and exposure of a CD4-induced epitope in a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope protein. J. Virol. 2001;75:5230–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.11.5230-5239.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards TG, Wyss S, Reeves JD, Zolla-Pazner S, Hoxie JA, Doms RW, Baribaud F. Truncation of the cytoplasmic domain induces exposure of conserved regions in the ectodomain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope protein. J. Virol. 2002;76:2683–91. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.6.2683-2691.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan MA, Carruth LM, Rowell JF, Yu X, Siliciano RF. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope protein endocytosis mediated by a highly conserved intrinsic internalization signal in the cytoplasmic domain of gp41 is suppressed in the presence of the Pr55gag precursor protein. J. Virol. 1996;70:6547–56. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.6547-6556.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg D, Wesson M. The most highly amphiphilic alpha-helices include two amino acid segments in human immunodeficiency virus glycoprotein 41. Biopolymers. 1990;29:171–7. doi: 10.1002/bip.360290122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freed EO, Martin MA. Virion incorporation of envelope glycoproteins with long but not short cytoplasmic tails is blocked by specific, single amino acid substitutions in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix. J. Virol. 1995;69:1984–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1984-1989.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freed EO, Martin MA. Domains of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix and gp41 cytoplasmic tail required for envelope incorporation into virions. J. Virol. 1996;70:341–51. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.341-351.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabuzda DH, Lever A, Terwilliger E, Sodroski J. Effects of deletions in the cytoplasmic domain on biological functions of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoproteins. J. Virol. 1992;66:3306–15. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.6.3306-3315.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallaher WR, Ball JM, Garry RF, Griffin MC, Montelaro RC. A general model for the transmembrane proteins of HIV and other retroviruses. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1989;5:431–40. doi: 10.1089/aid.1989.5.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawrisch K, Han KH, Yang JS, Bergelson LD, Ferretti JA. Interaction of peptide fragment 828−848 of the envelope glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type I with lipid bilayers. Biochemistry. 1993;32:3112–8. doi: 10.1021/bi00063a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch VM, Edmondson P, Murphey-Corb M, Arbeille B, Johnson PR, Mullins JI. SIV adaptation to human cells. Nature. 1989;341:573–4. doi: 10.1038/341573a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollier MJ, Dimmock NJ. The C-terminal tail of the gp41 transmembrane envelope glycoprotein of HIV-1 clades A, B, C, and D may exist in two conformations: an analysis of sequence, structure, and function. Virology. 2005;337:284–96. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter E. gp41, A Multifunctional Protein Involved in HIV Entry and Pathogenesis. In: Korber B, Hahn B, Foley B, Mellors JW, Leitner T, Myers G, McCutchan F, Kuiken CL, editors. “Human Retroviruses and AIDS”. Vol. 1. Theoretical Biology and Biophysics Group, Los Alamos National Laboratory; Los Alamos: 1997. pp. IIIpp. 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter E, Swanstrom R. Retrovirus envelope glycoproteins. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1990;157:187–253. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-75218-6_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110:673–87. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia V, Sarkar S, Gupta P, Montelaro RC. Rational site-directed mutations of the LLP-1 and LLP-2 lentivirus lytic peptide domains in the intracytoplasmic tail of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 indicate common functions in cell-cell fusion but distinct roles in virion envelope incorporation. J. Virol. 2003;77:3634–46. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.6.3634-3646.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia V, Sarkar S, Gupta P, Montelaro RC. Antibody neutralization escape mediated by point mutations in the intracytoplasmic tail of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41. J. Virol. 2005;79:2097–107. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.4.2097-2107.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy RC, Henkel RD, Pauletti D, Allan JS, Lee TH, Essex M, Dreesman GR. Antiserum to a synthetic peptide recognizes the HTLV-III envelope glycoprotein. Science. 1986;231:1556–9. doi: 10.1126/science.3006246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliger Y, Shai Y. A leucine zipper-like sequence from the cytoplasmic tail of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein binds and perturbs lipid bilayers. Biochemistry. 1997;36:5157–69. doi: 10.1021/bi962935r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama T, Wooley DP, Naidu YM, Kestler HW, 3rd, Daniel MD, Li Y, Desrosiers RC. Significance of premature stop codons in env of simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 1989;63:4709–14. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.11.4709-4714.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong PD, Wyatt R, Majeed S, Robinson J, Sweet RW, Sodroski J, Hendrickson WA. Structures of HIV-1 gp120 envelope glycoproteins from laboratory-adapted and primary isolates. Structure Fold Des. 2000;8:1329–39. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00547-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambele M, Labrosse B, Roch E, Moreau A, Verrier B, Barin F, Roingeard P, Mammano F, Brand D. Impact of natural polymorphism within the gp41 cytoplasmic tail of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 on the intracellular distribution of envelope glycoproteins and viral assembly. J. Virol. 2007;81:125–40. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01659-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SF, Ko CY, Wang CT, Chen SS. Effect of point mutations in the N terminus of the lentivirus lytic peptide-1 sequence of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane protein gp41 on Env stability. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:15363–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201479200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Verges S, Camus G, Blot G, Beauvoir R, Benarous R, Berlioz-Torrent C. Tail-interacting protein TIP47 is a connector between Gag and Env and is required for Env incorporation into HIV-1 virions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:14947–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602941103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luciw PA, Shaw KE, Shacklett BL, Marthas ML. Importance of the intracytoplasmic domain of the simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) envelope glycoprotein for pathogenesis. Virology. 1998;252:9–16. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luciw PA, Shaw KE, Unger RE, Planelles V, Stout MW, Lackner JE, Pratt-Lowe E, Leung NJ, Banapour B, Marthas ML. Genetic and biological comparisons of pathogenic and nonpathogenic molecular clones of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIVmac). AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1992;8:395–402. doi: 10.1089/aid.1992.8.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mammano F, Kondo E, Sodroski J, Bukovsky A, Gottlinger HG. Rescue of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix protein mutants by envelope glycoproteins with short cytoplasmic domains. J. Virol. 1995;69:3824–30. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3824-3830.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manrique JM, Celma CC, Affranchino JL, Hunter E, Gonzalez SA. Small variations in the length of the cytoplasmic domain of the simian immunodeficiency virus transmembrane protein drastically affect envelope incorporation and virus entry. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2001;17:1615–24. doi: 10.1089/088922201753342022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marthas ML, Banapour B, Sutjipto S, Siegel ME, Marx PA, Gardner MB, Pedersen NC, Luciw PA. Rhesus macaques inoculated with molecularly cloned simian immunodeficiency virus. J Med Primatol. 1989;18:311–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MA, Cloyd MW, Liebmann J, Rinaldo CR, Jr., Islam KR, Wang SZ, Mietzner TA, Montelaro RC. Alterations in cell membrane permeability by the lentivirus lytic peptide (LLP-1) of HIV-1 transmembrane protein. Virology. 1993;196:89–100. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MA, Garry RF, Jaynes JM, Montelaro RC. A structural correlation between lentivirus transmembrane proteins and natural cytolytic peptides. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1991;7:511–9. doi: 10.1089/aid.1991.7.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller K, Duffy I, Duprex P, Rima B, Beschorner R, Fauser S, Meyermann R, Niewiesk S, ter Meulen V, Schneider-Schaulies J. Recombinant measles viruses expressing altered hemagglutinin (H) genes: functional separation of mutations determining H antibody escape from neurovirulence. J. Virol. 2001;75:7612–20. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.16.7612-7620.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami T, Ablan S, Freed EO, Tanaka Y. Regulation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Env-mediated membrane fusion by viral protease activity. J. Virol. 2004;78:1026–31. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.2.1026-1031.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami T, Freed EO. Genetic evidence for an interaction between human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix and alpha-helix 2 of the gp41 cytoplasmic tail. J. Virol. 2000a;74:3548–54. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.8.3548-3554.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami T, Freed EO. The long cytoplasmic tail of gp41 is required in a cell type-dependent manner for HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein incorporation into virions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000b;97:343–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno H, Aguilar RC, Fournier MC, Hennecke S, Cosson P, Bonifacino JS. Interaction of endocytic signals from the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein complex with members of the adaptor medium chain family. Virology. 1997;238:305–15. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piller SC, Dubay JW, Derdeyn CA, Hunter E. Mutational analysis of conserved domains within the cytoplasmic tail of gp41 from human immunodeficiency virus type 1: effects on glycoprotein incorporation and infectivity. J. Virol. 2000;74:11717–23. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.24.11717-11723.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]