Abstract

We examined the relation between child maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI). Participants were 86 adolescents who completed measures of child maltreatment, self-criticism, perceived criticism, depression, and NSSI. Analyses revealed significant, small-to-medium associations between specific forms of child maltreatment (physical neglect, emotional abuse, and sexual abuse) and the presence of a recent history of NSSI. Emotional and sexual abuse had the strongest relations with NSSI, and the data supported a theoretical model in which self-criticism mediates the relation between emotional abuse and engagement in NSSI. Specificity for the mediating role of self-criticism was demonstrated by ruling out alternative mediation models. Taken together, these results indicate that several different forms of childhood maltreatment are associated with NSSI and illuminate one mechanism through which maltreatment may be associated with NSSI. Future research is needed to test the temporal relation between maltreatment and NSSI and should aim to identify additional pathways to engagement in NSSI.

Keywords: self-injury, child abuse, criticism, self-harm, self-mutilation, suicide

1. Introduction

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), which refers to direct and deliberate harm of bodily tissue in the absence of suicidal intent, is a major public health problem in the U.S. and around the world. Data suggest that approximately 4% of adults in the U.S. population exhibit NSSI (Briere & Gil, 1998; Klonsky, et. al., 2003), and that adolescents are at even higher risk, with approximately 12–21% reporting a lifetime history of NSSI (Ross & Heath, 2002; Whitlock et. al., 2006; Zoroglu et al., 2003). Recent research has begun to systematically describe the form and function of NSSI (Brown, Comtois & Linehan, 2002; Nock & Prinstein, 2004, 2005); however, the potential pathways to this behavior are not well understood. One consistently reported relation is that between a history of child maltreatment, defined here as neglect and abuse during childhood, and the development of NSSI. For instance, sexual abuse has shown a strong association with different forms of self-injury, including NSSI (Bergen et. al 2003; Nock & Kessler, 2006; Peters and Range, 1995; Yates, 2004), while physical abuse has been associated with such outcomes in some studies (e.g., Joiner et al., 2007) but not others (e.g., Nock & Kessler, 2006).

There are at least two important limitations of prior research in this area. First, the relation between different forms of child maltreatment and NSSI remains unclear, as most studies examine only one type of neglect or abuse. This makes it difficult to compare results across studies. Examining the relations between specific forms of child maltreatment and NSSI within a single study provides more detailed information about the relative magnitude of these associations and may facilitate greater understanding of how and why these constructs are related. Second, beyond knowing that child maltreatment is related to NSSI, it is important scientifically and clinically to better understand the factors that mediate or explain this relation. The potential mechanisms involved may vary depending on the type of neglect or abuse in question and variability among individual cases also is likely. Careful study and delineation of the mediators of these relations is an important and necessary step in understanding how NSSI might develop, and in informing prevention and intervention programs in the future.

Prior work suggests that people most often engage in NSSI for the purposes of emotion regulation or social communication (Brown et al., 2002; Nock & Prinstein, 2004, 2005). However, what has not been explained is why some individuals choose NSSI to achieve these ends rather than other behaviors that might serve similar functions, such as alcohol/drug use or bingeing/purging. One possibility is that some people select NSSI due to the directly self-injurious nature of this behavior, and that they learn to do so via modeling of earlier abuse by others. In other words, individuals who are excessively criticized and verbally or emotionally abused may, over time, learn to engage in excessive self-criticism and use NSSI as a form of direct “self abuse.”

For instance, people who experience maltreatment during childhood in the form of repeated insults, excessive criticism, or some form of physical abuse may come to adopt a similarly critical view of themselves over time through modeling the behavior of those who criticized and abused them. This could lead to the development of a self-critical cognitive style, and may ultimately manifest in the engagement in NSSI as an extreme form of self-punishment or self-abuse whenever they disapprove of their own behavior. NSSI is undoubtedly a multi-determined behavior that cannot be explained through one simple pathway such as this, but the examination of multiple pathways, such as the one proposed here, is necessary to begin to understand this dangerous behavior.

According to this model, the presence of child maltreatment is related to later engagement in NSSI during adolescence, and this relation is mediated by the presence of a self-critical cognitive style. We are proposing that it is self-criticism specifically that would mediate this relation given the directly self-abusive nature of NSSI. Beyond demonstrating mediation, the case for self-criticism as a mechanism through which maltreatment is associated with NSSI would be strengthened considerably if we were able to demonstrate specificity of this proposed mechanism by ruling out plausible alternatives (see Kazdin & Nock, 2003). For instance, we would first want to show that the alternative model in which maltreatment mediates the relation between self-criticism and NSSI is not supported. In addition, we would want to rule out other plausible alternative mediators. For instance, it is possible that it is not self-criticism per se, but the more general perception of criticism from others could also explain (i.e., mediate) this relation. The demonstration of such a relation would weaken the case for proposing self-criticism as a specific mediator. It is also possible that the relation between child maltreatment, self-criticism, and NSSI could be explained by the more general presence of major depression. Confidence in the importance of self-criticism as a specific mediator of the relation between maltreatment and NSSI would be strengthened if such relations existed even after taking the presence of major depression into account. We sought to test this theoretical model as well as these alternative explanations of the data in the current study.

The first goal of this study was to document the extent to which different types of childhood abuse and neglect, including: sexual, physical, and emotional abuse, as well as physical and emotional neglect, are associated with the presence of NSSI. The second goal was to test a mediation model in which adolescent self-criticism mediates the relation between childhood maltreatment and the presence of NSSI during adolescence. Prior work by Hooley and colleagues (2002) has shown that self-harming adolescents are more likely to tolerate physical pain in an experimental study if they believe that they are bad, flawed, and defective. The current study builds on this earlier work by (a) examining such self-criticism as a potential mediator in the relation between childhood maltreatment and NSSI, and (b) by testing alternative mediators, including perceived criticism from others and the presence of major depressive disorder, in order to test the specificity of self-criticism as a mediator. Through this investigation we hope to further illuminate the determinants of NSSI and to delineate a potential pathway through which NSSI can occur.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Ninety-four (73 female) adolescents aged 12–19 years (M=17.14, SD=1.88) were recruited via announcements posted in local psychiatric clinics, newspapers, community bulletin boards, and the internet. Of these, eight did not complete all study assessments and consequently were excluded from analysis. This sample size (N=86) provided statistical power to detect small, medium, and large effect sizes (r) of .15, .82, and .99, respectively, using two-tailed tests with alpha set at .05. The 86 adolescents providing data for this study (69 female; age in years: M=17.03, SD=1.92) self-reported ethnicity as: 73.3% European American, 3.5% African American, 7.0% Hispanic, 4.7% Asian American, 11.7% biracial or other ethnicity. All participants provided written informed consent to participate. Parental consent was obtained for those under the age of 18 years.

2.2. Assessment

2.2.1 Childhood Maltreatment

Childhood maltreatment was evaluated using the Child Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ; Bernstein et al., 1997), a widely-used 28-item measure that assesses five different forms of childhood trauma (Cronbach’s α in the current sample): physical abuse (α =.88), sexual abuse (α=.93), emotional abuse (α=.88), physical neglect (α=.73), and emotional neglect (α=.90). Participants report whether an item from the questionnaire is “never true,” “rarely true,” “sometimes true,” “often true,” or “very often true.” Prior work has supported the reliability and validity of the CTQ for identifying children who have suffered from each type of maltreatment (Bernstein et al., 1997).

2.2.2. Self-Criticism

Self-criticism was evaluated using the Self-Rating Scale (SRS; Hooley et al., 2002), an eight-item measure that assesses the extent to which an individual endorses self-critical statements (e.g., “sometimes I feel completely worthless,” “others are justified in criticizing me,” “I am socially inept and socially undesirable”). Participants respond to these items on a 0 to 7 scale, judging how strongly they agree with these statements. This measure demonstrated good internal consistency reliability in the current sample (Cronbach’s α =.88).

2.2.3. Perceived Criticism

Perceived criticism was evaluated using a brief, four-item measure called the Perceived Criticism Scale (PCS; Hooley & Teasdale, 1989). Participants were asked to respond to questions regarding criticism from others (e.g., “How critical do you think your mother is of you?”…“When your mother criticizes you, how upset do you get”) on a 1–10 scale. Responses were evaluated to determine how critical each subject perceived their primary guardian to be, and how affected each child was by that criticism. This measure demonstrated good internal consistency reliability in the current sample (Cronbach’s α =.74).

2.2.4. Non-Suicidal Self-Injury

Non-suicidal self-injury was assessed using the Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview (SITBI; Nock, Holmberg, Photos, & Michel, in press), a clinician-administered interview that assesses a range of SITB including both suicidal behaviors and NSSI. Given the focus of the current study, we examined only items related to the presence of NSSI in the past year (“In the past 12 months, have you done something to hurt yourself without intending to die?”). Prior work has revealed that the SITBI has strong inter-rater reliability (average κ=.99, r=1.0) and test-retest reliability over a 6-month period (average κ=.70, ICC=.44) (Nock, Holmberg, et al., in press). Construct validity also was demonstrated via strong correspondence between the SITBI and other measures of NSSI. Among those who reported engaging in NSSI, the functions of this behavior were assessed using the Functional Assessment of Self-Mutilation (Lloyd et al., 1997). The FASM includes 22 reasons for which a person may engage in NSSI, and the participant endorses each on a 0–3 scale. Confirmatory factor analysis and reliability analyses have demonstrated that these 22 items represent four over-arching functions of NSSI including automatic negative reinforcement, automatic positive reinforcement, social negative reinforcement, and social positive reinforcement (Nock & Prinstein, 2004), and subsequent work has supported the construct validity of these four functions (Nock & Prinstein, 2005).

2.2.5. Depression

If our mediation model showing that self-criticism mediates the relation between child maltreatment and NSSI is supported, it would be important to rule out the possibility that this relation is accounted for by the more general experience of depression. In order to test this, the presence of a major depressive disorder among participants was measured using major depressive disorder module of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Aged Children – Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL; Kaufman, Birmaher, Brent, Rao, & Ryan). K-SADS-PL interviews were conducted by the last author and four trained and supervised research assistants, and independently rated interviews showed excellent inter-rater reliability (average κ = .93).

2.3. Data Analyses

The associations between childhood maltreatment and NSSI were examined by calculating the zero-order correlations among these constructs. The types of maltreatment that were significantly correlated with NSSI were further tested in mediation models following standard methods for such tests outlined in prior research (Baron & Kenny, 1986; Holmbeck, 1997; Kazdin & Nock, 2003). Specifically, four criteria had to be met: (1) the independent variable must be correlated with the dependent variable; (2) the independent variable must be correlated with the potential mediator; (3) the dependent variable must be correlated with the potential mediator; and (4) if the first three conditions are met, it must be shown that the relation between the independent and dependent variable decreases significantly with the potential mediator in the model while the relation between the mediator and dependent variable remains.

3. Results

3.1. Childhood Maltreatment and NSSI

Correlation analyses revealed small to medium relations between the different types of child maltreatment and the presence of NSSI within the past year (see Table 1). More specifically, physical neglect, emotional abuse, and sexual abuse were significantly associated with NSSI, while physical abuse and emotional neglect had small, non-significant relations with NSSI.

Table 1.

Zero-order Correlations between Child Maltreatment and NSSI

| NSSI | |

|---|---|

| Emotional Neglect | .21 |

| Physical Neglect | .22* |

| Emotional Abuse | .28** |

| Physical Abuse | .17 |

| Sexual Abuse | .28** |

p<.05

p<.01

3.2. Potential Mediators of the Relation between Childhood Maltreatment and NSSI

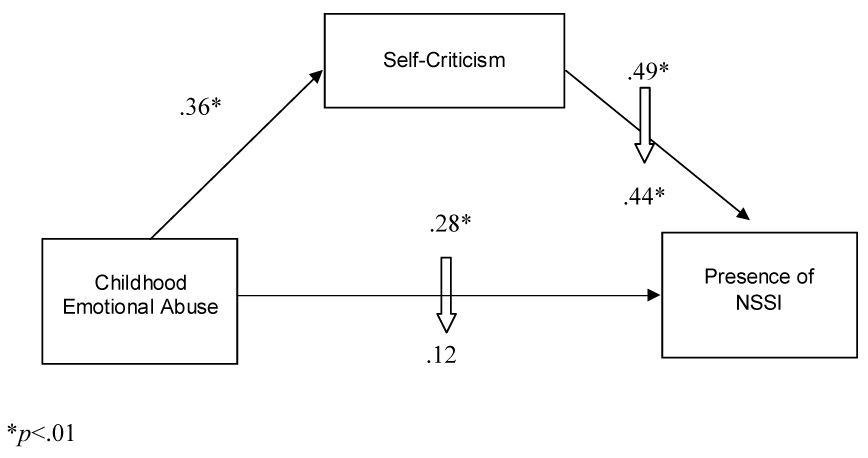

Given that emotional abuse, sexual abuse, and physical neglect were significantly correlated with presence of NSSI within the previous year, we next examined potential mediators of these relations. The results of these analyses (Table 2) revealed that self-criticism was strongly associated with both emotional abuse and frequency of NSSI. We followed this finding with a formal test of statistical mediation (Figure 1). This revealed that self-criticism statistically mediated the relation between emotional abuse during childhood and engagement in NSSI during adolescence (Sobel [1982] test, z=2.07, p<.05). Notably, analyses revealed that a mediation model with self-criticism as the independent variable and emotional abuse as the mediator in the prediction of NSSI was not supported (z=1.11, ns), supporting the specificity of the model presented in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Correlation Matrix of Potential Mediators

| Perceived Criticism | Self-Criticism | |

|---|---|---|

| NSSI | .18 | .48* |

| Physical Neglect | .03 | .16 |

| Emotional Abuse | .35* | .36* |

| Sexual Abuse | .20 | .12 |

p<.01

Figure 1.

Self-critical cognitive style mediates the relation between emotional abuse and NSSI

Analyses also revealed that although higher scores on the perceived criticism measure were associated with a history of emotional abuse, they were not associated with engagement in NSSI (Table 2), suggesting that while self-criticism mediates the relation between emotional abuse and NSSI perceived criticism does not, further supporting the specificity of self-criticism.

In order to test whether the mediating role of self-criticism remains even after controlling for the presence of major depression, we analyzed the mediation model presented in Figure 1 with the presence of major depression (coded 0,1) statistically controlled in the first step of each analysis. These analyses revealed that emotional abuse was no longer significantly related to NSSI (β=.16, ns), precluding a formal test of mediation. However, although self-criticism and depression were significantly related (r= 42, p<.001), it is important to note that they were not completely overlapping (sharing only 17.6% of their variance), and that self-criticism continued to predict NSSI even when depression was controlled in the model (β=.37, p<.001). These findings suggest that self-criticism continues to be significantly predictive of NSSI even after accounting for the presence of major depression.

Finally, consistent with the view that self-criticism may be related to NSSI due to attempts at “self-abuse” or “self-punishment,” we found that scores on the self-criticism measure were significantly associated with participants’ endorsement of self-punishment as a motive for NSSI on the FASM (r=.51, p<.001), but not with the more general functions of NSSI such as automatic negative reinforcement (r=.04, ns), automatic positive reinforcement (excluding the self-punishment item; r=.11, ns), social negative reinforcement (r=.14, ns), and social positive reinforcement (r=-.08, ns).

4. Discussion

NSSI is a serious problem among adolescents around the world, yet little is known about the determinants of these behaviors. Our results indicate that both sexual abuse and physical neglect are associated with NSSI, which is consistent with some prior research on this relation (Joiner et al., 2007; Lipschitz et. al. 1999; Simpson & Porter, 1992). This investigation is the first to our knowledge to also document a strong relation between childhood emotional abuse and NSSI. Physical abuse and emotional neglect were not significantly associated with the presence of NSSI, suggesting that not all types of child maltreatment are associated with NSSI. An important next step will be to better understand why some types of maltreatment, but not others, are related to engagement in NSSI.

Expanding upon these results, analyses revealed that the relation between childhood emotional abuse and engagement in NSSI during adolescence is partially explained by the presence of a self-critical cognitive style. Emotional abuse during a child’s formative years could result in a tendency to internalize critical thinking toward the self. In the face of stressful events, adolescents who have developed such a cognitive style may be more likely to engage in NSSI for self-punishment. These findings are consistent with prior work on the relations between self-criticism and both eating disordered behavior (Dunkley & Grilo, in press) and suicidal behavior (Grilo et al., 1999). Our study extends this earlier work and provides preliminary support for a model in which self-criticism is a specific mechanism through which early abuse is associated with subsequent NSSI. Of course, like these earlier studies, ours is cross-sectional and therefore no inferences can be drawn about the temporal relations among these constructs. Moreover, the presence of depression was an important factor in this process and accounted for at least part of the relation between emotional abuse and NSSI, although self-criticism continued to relate to NSSI even in the presence of depression. Overall, these preliminary findings lay a foundation for future research on the relations among child maltreatment and self-injurious behaviors.

These results must be considered within the context of the limitations inherent in our methods. One important limitation that bears repeating is that our variables were measured cross-sectionally. This makes it impossible to determine the directionality of the observed relations. Alternate conclusions can be posited from the data if different potentially causal relationships are taken into consideration. For example, NSSI may produce a self-critical style, in contrast to our assumption that the association exists in the opposite direction.

The use of retrospective self-report data also introduces several well-known limitations, such as error due to forgetting and biased recall. Recent systematic reviews suggest that although retrospective recall of childhood events can provide useful and fairly accurate data, there is a significant tendency to under-report instances of maltreatment (see Brewin, Andrews, & Gotlib, 1993; Hardt & Rutter, 2004). Because of their ages, our adolescent participants were not as temporally removed from the reported events as adult participants; however, the tendency to under-report their engagement in self-injurious behaviors may reduce the effect sizes of the relations in this study. A final limitation of this study is that all of our participants were adolescents and young adults who agreed to participate in a lab-based study. Our findings may not generalize to younger or older populations or to those unwilling to participate in research studies.

These limitations notwithstanding, the conclusions presented in this paper have important implications for NSSI research. Other cognitive characteristics must be investigated as potential mediators between child maltreatment and NSSI to determine possible warning signs for engaging in NSSI and to help identify malleable risk factors. Discovering such factors can help to develop better methods for both identifying and treating NSSI. Indeed, self-injurious thoughts and behaviors are notoriously difficult to detect, in part because many individuals are reluctant to report on their engagement in such behaviors and so researchers and clinicians must rely on other methods for identifying who is most at risk (e.g., Nock & Banaji, in press). Toward this end, knowledge of which proximal factors (e.g., self-criticism) might explain the process through which distal events (e.g., maltreatment) might ultimately influence engagement in NSSI can help researchers and clinicians better identify which people experiencing the distal event will be most at risk for NSSI.

In additional, knowing the processes through which NSSI may develop and be maintained can inform treatment efforts aimed at decreasing and preventing NSSI. In the current case, it is possible that family interventions directed at decreasing child maltreatment may decrease the likelihood of NSSI among children and also that psychosocial interventions aimed at decreasing adolescent self-criticism may be effective in treating or preventing NSSI. Moreover, such decreases in self-criticism may represent one mechanism through which the treatment of NSSI leads to therapeutic change (Kazdin & Nock, 2003). Advances are needed in many areas in scientific and clinical efforts to understand, assess, and treat NSSI, and this study represents one small step toward such progress.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from the William F. Milton Fund and William A. Talley Fund of Harvard University and with partial support from National Institute of Mental Health (1R03MH076047-01).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergen HA, Martin G, Richardson AS, Allison S, Roeger L. Sexual abuse and suicidal behavior: A model constructed from a large community sample of adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42:1301–1309. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000084831.67701.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Ahluvalia T, Pogge D, Handelsman L. Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:340–348. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199703000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Andrews B, Gotlib IH. Psychopathology and early experience: a reappraisal of retrospective reports. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113:82–98. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, Gil E. Self-mutilation in clinical and general population samples: prevalence, correlates, and functions. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68:609–620. doi: 10.1037/h0080369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MZ, Comtois KA, Linehan MM. Reasons for suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in women with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:198–202. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkley DM, Grilo CM. Self-criticism, low self-esteem, depressive symptoms, and over-evaluation of shape and weight in binge eating disorder patients. Behaviour Research and Therapy. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.01.017. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, Fehon DC, Lipschitz DS, Martino S, McGlashan TH. Correlates of suicide risk in adolescent inpatients who report a history of child abuse. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1999;40:422–428. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(99)90085-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardt J, Rutter M. Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: review of the evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:260–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN. Toward terminological, conceptual, and statistical clarity in the study of mediators and moderators: examples from the child-clinical and pediatric psychology literatures. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:599–610. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.4.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooley JM, Ho DT, Slater JA, Lockshin A. Pain insensitivity and self-harming behavior. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Research in Psychopathology.2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hooley JM, Teasdale JD. Predictors of relapse in unipolar depressives: expressed emotion, marital distress, and perceived criticism. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1989;98:229–235. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.98.3.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Sachs-Ericsson NJ, Wingate LR, Brown JS, Anestis MD, Selby EA. Childhood physical and sexual abuse and lifetime number of suicide attempts: A persistent and theoretically important relationship. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:539–547. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent DA, Rao U, Ryan ND. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Age Children, Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Nock MK. Delineating mechanisms of change in child and adolescent therapy: methodological issues and research recommendations. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44:1116–1129. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, Oltmanns TF, Turkheimer E. Deliberate self-harm in a nonclinical population: prevalence and psychological correlates. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:1501–1508. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipschitz D, Winegar RK, Nicolaou AL, Hartnick E, Wolfson M, Southwick SM. Perceived abuse and neglect as risk factors for suicidal behavior in adolescent inpatients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1999;187:32–39. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199901000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd E, Kelley ML, Hope T. Self-mutilation in a community sample of adolescents: Descriptive characteristics and provisional prevalence rates. Paper presented at the Annual meeting of the Society for Behavioral Medicine; New Orleans, LA. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Banaji MR. Assessment of self-injurious thoughts using a behavioral test. American Journal of Psychiatry. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.5.820. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Holmberg EB, Photos VI, Michel BD. The Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview: Development, reliability, and validity of a new measure. Psychological Assessment. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.3.309. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Kessler RC. Prevalence of and risk factors for suicide attempts versus suicide gestures: Analysis of the National Comorbidity Survey. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:616–623. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Prinstein MJ. A functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:885–890. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Prinstein MJ. Clinical features and behavioral functions of adolescent self-mutilation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:140–146. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters DK, Range LM. Childhood Sexual Abuse and Current Suicidality in College Women and Men. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1995;19:335–341. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(94)00133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross S, Heath N. A study of the frequency of self-mutilation in a community sample of adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2002;31:67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson CA, Porter GL. Self-mutilation in children and adolescents. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic. 1992;45:428–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic intervals for indirect effects in structural equations models. In: Leinhart S, editor. Sociological methodology 1982. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock J, Eckenrode J, Silverman D. Self-injurious behaviors in a college population. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1939–1948. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates TM. The developmental psychopathology of self-injurious behavior: Compensatory regulation in posttraumatic adaptation. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24:35–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoroglu SS, Tuzun U, Sar V, Tutkun H, Savacs HA, Ozturk M, et al. Suicide attempt and self-mutilation among Turkish high school students in relation with abuse, neglect and dissociation. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2003;57:119–126. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1819.2003.01088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]