Abstract

We examined if life-long mild caloric restriction (CR) alone or with voluntary exercise prevents the age-related changes in catecholamine biosynthetic enzyme levels in the adrenal medulla and hypothalamus. Ten week-old Fisher-344 rats were assigned to: sedentary; sedentary+8% CR; or 8% CR+wheel running. Rats were euthanized at 6 or 24 months of age. Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) mRNA expression was 4.4-fold higher in the adrenal medullae and 60% lower in the hypothalamus of old sedentary rats compared to young (p<0.01). Life-long CR reduced the age-related decline in adrenomedullary TH by 50% (p<0.05), and completely reversed the changes in hypothalamic TH. Voluntary exercise, however, had no additional effect over CR. Since angiotensin II is involved in the regulation of catecholamine biosynthesis, we examined the expressions of angiotensin II receptor subtypes in the adrenal medulla. AT1 protein levels were 2.8-fold higher in the old animals compared to young (p<0.01), and while AT1 levels were unaffected by CR alone, CR+wheel running decreased AT1 levels by 50% (p<0.01). AT2 levels did not change with age, however CR+wheel running increased its level by 42% (p<0.05). These data indicate that a small decrease in daily food intake can avert age-related changes in catecholamine biosynthetic enzyme levels in the adrenal medulla and hypothalamus, possibly through affecting angiotensin II signaling.

Keywords: Tyrosine hydroxylase, Dopamine beta hydroxylase, Angiotensin II, Aging, Exercise, Caloric restriction

Introduction

Levels of catecholamine biosynthetic enzymes change with age both in the adrenal medulla and in the hypothalamus. We, as well as others, have reported that mRNA, protein levels and enzyme activity of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), the rate-limiting enzyme in catecholamine biosynthesis, are two- to three-fold higher in the adrenals of senescent rats compared with younger animals (Kedzierski and Porter, 1990; Tumer et al., 1992; Tumer and Larochelle, 1995; Voogt et al., 1990). In addition, dopamine beta-hydroxylase (DβH) is also upregulated in the adrenal medulla with age (Banerji et al., 1984; Tumer et al., 1999) and circulating catecholamines are elevated in both senescent humans and laboratory animals due to increased synthesis and release of these hormones from sympathetic ganglia and adrenals (Avakian et al., 1984; Esler M. et al., 1981; Hoeldtke and Cilmi, 1985; Ito et al., 1986; Ziegler et al., 1976). In contrast, aging has an opposite effect on hypothalamic TH biosynthesis. Unlike in the adrenal medulla, TH level and activity decrease in the hypothalamus with age (Reymond et al., 1984; Tumer et al., 1997a; Voogt et al., 1990). These changes in hypothalamic and adrenomedullary catecholamine biosynthesis may play an important role in the age-related increase in sympathetic nervous activity and could be a significant factor in the development of hypertension.

Exercise training reduces the risk of cardiovascular diseases, increases cardiovascular functional capacity in healthy subjects, as well as in most patients with cardiovascular disease, and it is beneficial in controlling hypertension (McHenry et al., 1990). Exercise training also lowers plasma norepinephrine concentration in elderly subjects with elevated baseline levels (Seals et al., 1994), and reduces both systolic and diastolic blood pressure in young and elderly hypertensive subjects (Hagberg and Seals, 1986; Tipton, 1999). We have previously demonstrated (Tumer et al., 1992) that long-term (10 weeks) treadmill exercise induces adaptive changes in young rats that lead to a decrease in TH expression and activity in the adrenal medulla, but the same training schedule failed to decrease the already elevated TH level and activity in the senescent rats. However, forced modes of exercise, like treadmill training, may cause physiological adaptations indicative of chronic stress (Moraska et al., 2000), and it is possible that the stressor effect of forced exercise is higher in senescent animals compared to young subjects abolishing the beneficial effects of exercise training. An alternative to forced exercise paradigms is to allow subjects free access to running wheels and allow exercising voluntarily for extended periods of time. Using this method, the stressor effects of forced training schedules can be avoided. A limitation of this model is that rats fed an ad libitum diet tend to abruptly decrease their running activity, however, a slight restriction in food intake (8−10%) has been shown to prevent this decline (Holloszy and Schechtman, 1991; Holloszy et al., 1985; McCarter et al., 1997).

Therefore, we studied rats who had free access to running wheels and whose caloric intake (CR) was restricted by 8% compared to rats fed ad libitum. Sedentary rats with 8% CR served as controls for the wheel running group. As an addition, this design also allowed us to examine the effects of life-long mild caloric restriction on catecholamine biosynthetic enzyme levels in the adrenal medulla and hypothalamus. We assessed TH and DβH expressions in the adrenal medulla and hypothalamus. The DNA-binding activities of activating protein-1 (AP-1) and cAMP-response element binding protein (CREB) transcription factors, which have a major role in the control of TH expression in stress (Sabban et al., 2004a, 2004b; Sabban and Kvetnansky, 2001) and exercise (Erdem et al., 2002b; Tumer et al., 2001) were measured in the adrenal medulla. In addition, changes in adrenomedullary angiotensin II (Ang II) AT1 and AT2 receptor subtype protein levels were also analyzed, since expressions and activities of TH and DβH are greatly influenced by Ang II (Jezova et al., 2003; Stachowiak et al., 1990; Takekoshi et al., 2000; Wong et al., 1990).

Materials and Methods

Animals

Experiments were conducted according to the Guiding Principles in the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and procedures were approved by the University of Florida's Institute on Animal Care and Use Committee. Male Fischer-344 rats were purchased from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN) at 10−11 weeks of age and were housed at the University of Florida (Gainesville, FL). One week after arriving at our facilities, rats were randomly assigned to one of the following three groups: sedentary, fed ad libitum (control, n = 20), sedentary, 8% CR (n = 20) or 8% CR plus wheel running (n = 20). Throughout the duration of the study, caloric intake of these latter two groups was adjusted accordingly each week, based on ad libitum caloric intake of the control group from the previous week. All animals were singly housed in a temperature-(20 ± 2.5°C) and light-controlled (12:12-h light-dark cycle) environment with unrestricted access to water. All sedentary rats were housed in standard rodent cages supplied by the University of Florida's Animal Care Services. Rats in the wheel running group were housed in cages equipped with Nalgene Activity Wheels (1.081 meters circumference) obtained from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA) and had free access to the wheels. Each wheel was equipped with a magnetic switch and an LCD counter that recorded the number of wheel revolutions. The number of revolutions was recorded for each animal daily. Rats were sacrificed at 6 (adult) or 24 months (senescence) of age. The age of 24 months for sacrifice was chosen, because it represents the mean life span for this species. At the time of sacrifice (24 months), at least 12 animals remained alive within each group, and survivability was similar in all experimental groups.

Daily energy expenditure (DEE)

Daily energy expenditure (DEE) was estimated by employing the doubly-labeled water technique as previously described (Speakman, 1997, 1998) in sedentary and wheel running rats at 10 months of age.

Tissue preparation

Animals were anesthetized with pentobarbital (90 mg/kg ip); adrenal glands and the hypothalamus were removed quickly and immediately frozen by immersion in liquid nitrogen. Tissues were stored at −80°C. At the time of the assay, adrenal glands were decapsulated, and the medullae were separated from the cortex. Adrenal medullae and hypothalamus were weighed and homogenized in 100 µl of phosphate buffer (2 mM NaPO4, 0.2% Triton, pH 7.0). There was insufficient tissue from an individual animal to measure protein levels, mRNA and electrophoretic mobility shift assays. Therefore the tissues were split for the different assays using portions from 6−8 animals for each different biochemical assay.

TH and DβH mRNA levels

TH and DβH mRNA levels were determined using Northern blot analysis as previously described (Tumer and Larochelle, 1995; Erdem et al., 2002b). Briefly, total cellular RNA was extracted using Tri-reagent (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and the isolated RNA was quantified by spectrophotometry. Membranes were hybridized with 32P random primer-generated probes. After hybridization, the membranes were washed and exposed to phospho screen for 24 hours using Phospho Imager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyville, CA). Screens were scanned and analyzed using Image Quant software (Molecular Dynamics).

Western blot

TH, AT1 and AT2 protein levels were determined using Western blot as previously described (Tumer et al., 1992, Erdem et al., 2002b). Briefly, an equal amount of protein for each sample was separated by 10 % SDS-PAGE, transferred onto a polyvinylidine difluoride membrane and blocked with 5% skimmed milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20. Blots were incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-TH polyclonal antibody (Pel-Freez Biologicals, Rogers, AR), anti-AT1 or AT2 antibodies (Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA). The bound antibodies were detected by chemiluminescence.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

The AP-1 and CREB sequences (25 oligomers) from Promega (Madison, WI) were 32P 3' end labeled using the End Labeling System (Promega) as previously described (Tumer et al., 1997b, Erdem et al., 2002b). Probe (3.5 pg, 10 000 cpm) was incubated in 10 µL of 4% glycerol, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris – HCl, pH 7.5, 0.05 mg/mL poly(dI-dC) and 20 µg of nuclear protein extract for 20 min at room temperature. In some experiments, nuclear extract was preincubated with 3000-fold excess of unlabeled AP-1 or CREB sequences for 10 min at room temperature. Samples were electrophoretically resolved on a 5% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel (80:1; acrylamide: BIS in 89 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 89mM boric acid, 2mM EDTA for 30 min). The gels were dried, exposed to a phosphoimaging screen, scanned by Phospho Imager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA) and analyzed by Image Quant Software (Molecular Dynamics). Tissue samples were pooled from six animals in each group due to the small amount of nuclear fraction available from the adrenal medullae. Therefore, statistical evaluation of these results was not possible.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SE. Differences between experimental groups were evaluated using analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post hoc test. The criterion for significance was p<0.05.

Results

Running activity, daily energy expenditure and body weights

The average distance run per day was recorded in the wheel running group throughout the duration of the study. This portion of the data was previously published by us (Judge et al., 2005; Seo et al., 2006). Briefly, peak running activity occurred at 6 months of age (∼2500 meters/day), but running activity was maintained at an average of 1145 ± 248 meters/day for the remainder of the study. At 10 months of age, runners exhibited a significantly higher daily energy expenditure (202 ± 31 kJ/day) compared with sedentary, 8% CR rats (121± 22 kJ/day; p < 0.05). In addition, wheel-running animals weighed significantly less than their sedentary counterparts, while there was no significant difference in body weight between the sedentary control and sedentary CR groups. At 24 months of age, sedentary control and sedentary CR rats weighed 381±21 g and 383±9 g, respectively, while the average weight in the CR-running group was 339±8 g (p<0.05 vs. sedentary CR).

TH and DβH expression in the adrenal medulla

TH mRNA expression increased significantly with age in the adrenal medulla, and it was 4.4 times higher in the 24-month-old sedentary rats (n=6) compared with the 6-month-old rats (n=8, p<0.01, Fig. 1A). 8% CR significantly reduced the age-related increase in TH expression; TH mRNA was 30% less in the 24-month-old CR rats (n=6) compared to the 24-month-old controls (p<0.05). Voluntary wheel-running with 8% CR had no additional effect compared with CR alone; the TH mRNA level in this group (n=6) was 35% lower than in the 24-month-old control group (p<0.05, Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Changes in TH mRNA (panel A) and protein (panel B) levels in the adrenal medulla with age and in response to caloric restriction (CR) and exercise (Ex) as measured with Northern and Western blot analysis and expressed in percentage of the 6-month-old control group. TH mRNA and protein levels increased significantly with age, but CR and CR plus exercise reduced the age-related TH upregulation. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 vs. 6-month-old control. #p<0.05 vs. 24-month-old control.

TH protein levels paralleled the changes in TH mRNA expression; TH protein was 1.8-fold higher in the 24-month-old control group compared to the 6-month-old group (p<0.01, Fig. 1B). 8% CR prevented the age-related increase in TH protein, and voluntary wheel running had no additional effect over CR (Fig. 1B, n=6 in all groups).

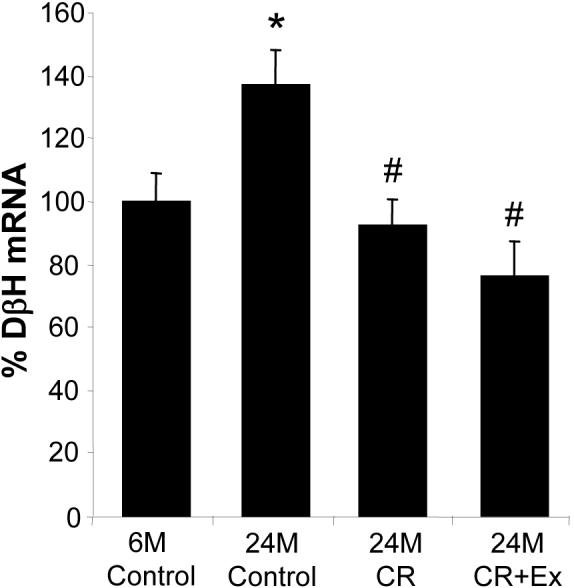

DβH was also upregulated in the adrenal medulla with age, the DβH mRNA level was 1.4-fold higher in the 24-month-old control rats (n=6) compared to the 6-month-old rats (n=6, p<0.05, Fig. 2). 8% CR completely abolished this increase (n=8), and voluntary exercise had no additional effect over CR (n=8, Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Changes in DβH mRNA levels in the adrenal medulla with age and in response to caloric restriction (CR) and exercise (Ex) as measured with Northern blot analysis and expressed as percentage of DβH mRNA in the 6-month-old control group. DβH mRNA increased significantly with age, but CR and CR plus exercise prevented the age-related DβH upregulation. *p<0.05 vs. 6-month-old control. #p<0.05 vs. 24-month-old control.

AP-1 and CREB transcription factors in the adrenal medulla

Changes in the AP-1 or CREB transcription factor bindings as measured with electrophoretic mobility shift assay were not parallel with alterations of TH and DβH expression in the adrenal medulla. AP-1 binding markedly decreased with age and was only 29% in the 24-month-old control group compared with the 6-month-old group (100%). CR alone or in combination with wheel running had no effect on AP-1, binding activities were 31 and 32% in these groups compared with the 6-month-old group. CREB binding also decreased with age, and was only 64% in the 24-month-old control rats compared with 6-month-old rats (100%). CR alone or in combination with wheel running had no effect on CREB, binding activities were 55 and 57% in these groups compared with the 6-month-old group.

AT1 and AT2 receptor levels in the adrenal medulla

AT1 receptor protein levels increased significantly with age in the adrenal medulla, and it was 2.8-fold higher in the 24-month-old control group (n=6) compared to the 6-month-old group (n=7, p<0.01, Fig. 3A). Life-long 8% CR did not have an effect on AT1 levels (n=6), but 8% CR combined with voluntary wheel running completely abolished the age-related upregulation of AT1 (n=6, Fig. 3A). In contrast, AT2 receptor levels remained unchanged with age, but CR increased the expression of this receptor subtype in the adrenal medullae of 24-month-old rats (p<0.05) with no additional effects from exercise (Fig. 3B, n=6 in all groups).

Fig. 3.

Changes in AT1 (panel A) and AT2 (panel B) receptor protein levels in the adrenal medulla with age and in response to caloric restriction (CR) and exercise (Ex) as measured with Western blot analysis and expressed in percentage of the 6-month-old control group. AT1 protein increased significantly with age. 8% CR alone had no effect on AT1 levels, however CR in combination with voluntary wheel running prevented the age-related upregulation of AT1. AT2 protein levels did not change with age. However, 8% CR alone or in combination with exercise increased the levels of this receptor subtype. **p<0.01 vs. 6-month-old control. #p<0.05, ##p<0.01 vs. 24-month-old control.

TH and DβH expression in the hypothalamus

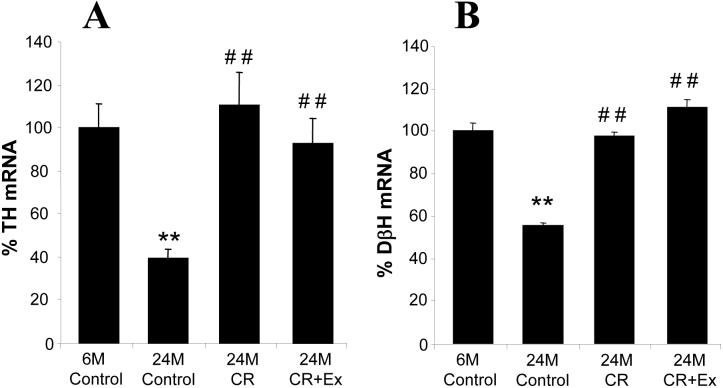

TH mRNA expression decreased significantly with age in the hypothalamus, and it was about 60% lower in the 24-month-old control rats compared with the 6-month-old rats (p<0.01, Fig. 4A). Life-long 8% CR completely prevented the age-related decline in TH expression, and voluntary wheel running had no additional effect compared with CR alone (Fig. 4A, n=8 in all groups).

Fig. 4.

Changes in TH (panel A) and DβH (panel B) mRNA levels in the hypothalamus with age and in response to caloric restriction (CR) and exercise (Ex) as measured with Northern blot analysis and expressed in percentage of the 6-month-old control group. Both TH and DβH mRNA levels decreased significantly with age, but CR and CR plus wheel running prevented the age-related TH downregulation. **p<0.01 vs. 6-month-old control. ##p<0.01 vs. 24-month-old control.

DβH was also downregulated in the hypothalamus with age, the DβH mRNA level was about 45% lower in the 24-month-old control rats (n=9) compared to the 6-month-old rats (n=9, p<0.01, Fig. 4B). 8% CR completely abolished this decrease (n=10), and voluntary exercise had no additional effect over CR (n=8, Fig. 4B).

Discussion

The major findings of this study are that age-related changes in the levels of catecholamine biosynthetic enzymes in the adrenal medulla and hypothalamus can be abolished with only 8% restriction in daily caloric intake, while life-long voluntary exercise doesn't have any additional effect over CR. In the adrenal medulla, age- and CR-related changes in TH are apparently not mediated by AP-1 and CREB transcription factors. However, increased levels of AT1 receptors may play a role in the age-related upregulation of adrenomedullary TH, while elevated expression of AT2 receptors may be involved in the beneficial effects of CR and exercise.

The risk for cardiovascular diseases increase with age (Franklin et al., 1997; Kannel and Gordan, 1978). In particular, the elderly do not regulate blood pressure as well as young people, and age-related increases in the prevalence of hypertension are associated with elevated morbidity and mortality (National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group 1994; Tuck, 1989). The elevation in blood pressure with age is attributable, at least in part, to an increase in sympathetic nervous activity (Esler M. et al., 2002; Esler M.D. et al., 1995; Seals and Dinenno, 2004), and sustained elevation of catecholaminergic activity requires increased levels of catecholamine biosynthesizing enzymes in the adrenal medulla and peripheral sympathetic ganglia. Our laboratory along with others have reported that TH and DβH mRNA, protein levels and enzyme activities are two- to three-fold higher in the adrenals of senescent rats compared with younger animals (Banerji et al., 1984; Kedzierski and Porter, 1990; Tumer et al., 1999; Tumer et al., 1992; Tumer and Larochelle, 1995; Voogt et al., 1990). The underlying mechanisms are not fully understood, but it seems that increased activity of the sympathetic nervous system and the elevated amount of acetylcholine released from preganglionic sympathetic nerve terminals innervating the chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla mediate, at least partially, the upregulation of TH and DβH (Dogan et al., 2004; Tumer et al., 1999). In addition, other mediators such as neuropeptide Y and Ang II may also be involved in the regulation of TH and DβH expression (Armando et al., 2004; Erdem et al., 2002a; Jezova et al., 2003; Tumer et al., 1999). Since elevated plasma catecholamine levels may be contributing to the increased prevalence of hypertension in the elderly, identification and inhibition of those mechanisms mediating the upregulation of catecholamine-synthesizing enzymes could help to develop new approaches for treatment of age-related hypertension.

In the present study, we set out to investigate the effect of life-long voluntary exercise on adrenomedullary TH and DβH expression in rats. Since rats fed ad libitum tend to decrease their running activity, we had to implement a slight caloric restriction to maintain physical activity in the runner group, and sedentary CR rats served as their controls. This experimental design also let us investigate the effects of life-long mild caloric restriction, although based on preliminary experiments, 8% CR without exercise wasn't expected to have significant effects on the rats. For example, it had no effect on body weight. However, our studies led to the surprising finding that even such a small decrease in food intake prevented the age-related increase in adrenomedullary TH and DβH expressions and eliminated the age-related decline in hypothalamic TH and DβH mRNA levels, while voluntary exercise had no additional effect over CR. These effects were apparently not due to changes in body weight. Despite the difference in bodyweight between wheel-running and sedentary groups, there was no additional effect over CR with respect to TH or DβH mRNA, and the body weights in the CR and control sedentary groups were almost identical. Due to our experimental design, we can't rule out the possibility that beneficial effects of exercise were masked by those of CR, and exercise alone could also prevent age-related changes in TH and DβH levels. In addition, CR alone may have increased home cage locomotor activity (Chen et al., 2005; McCarter et al., 1997), thus, we can't rule out the possibility that the observed effects of CR were also mediated by exercise even in those rats that did not have access to running wheels. Conversely, it is also possible that effects of exercise on catecholamine biosynthesis are diminishing with age as we found previously using a forced mode of exercise (Tumer et al., 1992).

To reveal the detailed mechanisms underlying age- and CR-related changes in adrenomedullary TH and DβH, we measured the binding activities of AP-1 and CREB transcription factors in nuclear extracts from adrenal medulla, since AP-1 and CREB play a central role in the regulation of TH and DβH expression during stress (Sabban et al., 2004a, 2004b; Sabban and Kvetnansky, 2001) and forced exercise training (Erdem et al., 2002b; Tumer et al., 2001). However, in the present study, we found that neither of these transcription factors is responsible for the observed changes in adrenomedullary TH and DβH levels with age or in response to CR. Despite the age-related increase of TH and DβH levels, both AP-1 and CREB binding activities decreased with age in the adrenal medulla. These results are in concert with our previous finding that AP-1 binding activity decreases with age in the adrenal medulla (Tumer et al., 1997b). Moreover, neither CR nor voluntary wheel running had any effect on AP-1 and CREB binding activities.

Expressions and activities of catecholamine biosynthetic enzymes in the adrenal medulla are also regulated by Ang II (Livett and Marley, 1993; Stachowiak et al., 1990). Both AT1 and AT2 receptor subtypes are expressed in the rat adrenal medulla with the predominance of AT2 receptors representing about 90% of total Ang II receptors (Israel et al., 1995; Jezova et al., 2003). In spite of this, the selective blockade of AT1 receptors is sufficient to prevent Ang II-induced catecholamine release in isolated rat adrenal glands (Wong et al., 1990), and long-term inhibition of this receptor subtype decreases both adrenomedullary TH mRNA and norepinephrine content (Armando et al., 2001, 2004; Jezova et al., 2003). In contrast, the role of the dominant AT2 receptor subtype in the regulation of adrenomedullary catecholamine biosynthesis is not clear, since both activation (Takekoshi et al., 2000, 2002) and inhibition (Jezova et al., 2003) of this receptor subtype were found to reduce TH expression and catecholamine biosynthesis.

In the present study, we wanted to test whether changes in catecholamine biosynthetic enzyme levels are accompanied by changes in AT1 and AT2 receptor levels in the adrenal medulla. Interestingly, we found that, parallel to changes in TH and DβH levels, adrenomedullary AT1 receptor expression increased markedly with age, but CR failed to have any effect on the expression of this receptor subtype. However, exercise, which had no additional effect on TH and DβH levels compared to CR, completely reversed the age-related upregulation of AT1. In contrast, AT2 receptor levels did not change with age, but were elevated by both CR and CR plus exercise. These results indicate the complexity of Ang II signaling and receptor crosstalk in the adrenal medulla and that further studies will be needed to reveal the details of this regulatory pathway. Nevertheless, our findings suggest that upregulation of adrenomedullary AT1 receptors with age may be involved in increased levels of catecholamine biosynthesis in the adrenal medulla considering that AT1 levels increased almost three-fold in the 24 month-old rats compared to 6-month-old rats and that previous studies clearly indicated that AT1 activation stimulates adrenomedullary catecholamine biosynthesis (Armando et al., 2001, 2004; Jezova et al., 2003). However, it is hard to explain why the marked reduction in AT1 expression caused by CR plus exercise is not reflected in decreased TH and DβH levels compared to CR alone. One explanation might be that the effects of exercise-induced AT1 downregulation are masked by other beneficial effects of CR. For example, elevated levels of AT2 receptors caused by CR may have an inhibitory effect on TH and DβH expression by opposing AT1 signaling (Takekoshi et al., 2000, 2002), therefore downregulation of AT1 receptors due to exercise does not have further effects on baseline TH and DβH levels.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that a surprisingly small decrease in daily food intake can prevent age-related changes in catecholamine biosynthetic enzyme levels in the adrenal medulla and hypothalamus. Interestingly, in our experimental model, long-term voluntary exercise was found to have no effect on adrenomedullary TH and DβH levels in addition to CR. However, the beneficial effects of exercise on the age-related changes in TH and DβH may have been masked by those of CR, and even though resting levels of catecholamine biosynthetic enzymes were not affected by voluntary wheel running, the marked exercise-induced downregulation of AT1 receptors in the adrenal medulla may have a significant effect on how aged animals respond to stimuli like stress that induces angiotensin II-mediated upregulation of catecholamine biosynthesis.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Medical Research Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs and by grants to Dr. Leeuwenburgh from the National Institute on Aging (R01-AG17994 and AG21042). The authors wish to thank Ms. Janet Wootten for editorial assistance and Dr. Sharon Judge, Dr. Tracey Phillips, Laurie Lanier, Young Mok Jang, and Dr. Barry Drew for their technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Armando I, Carranza A, Nishimura Y, Hoe KL, Barontini M, Terron JA, Falcon-Neri A, Ito T, Juorio AV, Saavedra JM. Peripheral administration of an angiotensin II AT(1) receptor antagonist decreases the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal response to isolation Stress. Endocrinology. 2001;142:3880–3889. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.9.8366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armando I, Jezova M, Bregonzio C, Baiardi G, Saavedra JM. Angiotensin II AT1 and AT2 receptor types regulate basal and stress-induced adrenomedullary catecholamine production through transcriptional regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1018:302–309. doi: 10.1196/annals.1296.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avakian EV, Horvath SM, Colburn RW. Influence of age and cold stress on plasma catecholamine levels in rats. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1984;10:127–133. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(84)90051-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerji TK, Parkening TA, Collins TJ. Adrenomedullary catecholaminergic activity increases with age in male laboratory rodents. J Gerontol. 1984;39:264–268. doi: 10.1093/geronj/39.3.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Steele AD, Lindquist S, Guarente L. Increase in activity during calorie restriction requires Sirt1. Science. 2005;310:1641. doi: 10.1126/science.1118357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogan MD, Sumners C, Broxson CS, Clark N, Tumer N. Central angiotensin II increases biosynthesis of tyrosine hydroxylase in the rat adrenal medulla. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;313:623–626. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdem SR, Broxson CS, Erdem A, Spar DS, Williams RT, Tumer N. The age-related discrepancy in the effect of neuropeptide Y on select catecholamine biosynthetic enzymes in the adrenal medulla and hypothalamus in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2002a;43:1280–1288. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00293-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdem SR, Demirel HA, Broxson CS, Nankova BB, Sabban EL, Tumer N. Effect of exercise on mRNA expression of select adrenal medullary catecholamine biosynthetic enzymes. J Appl Physiol. 2002b;93:463–468. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00627.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esler M, Hastings J, Lambert G, Kaye D, Jennings G, Seals DR. The influence of aging on the human sympathetic nervous system and brain norepinephrine turnover. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;282:R909–916. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00335.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esler M, Skews H, Leonard P, Jackman G, Bobik A, Korner P. Age-dependence of noradrenaline kinetics in normal subjects. Clin Sci (Lond) 1981;60:217–219. doi: 10.1042/cs0600217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esler MD, Turner AG, Kaye DM, Thompson JM, Kingwell BA, Morris M, Lambert GW, Jennings GL, Cox HS, Seals DR. Aging effects on human sympathetic neuronal function. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:R278–285. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.268.1.R278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin SS, Gustin W. t., Wong ND, Larson MG, Weber MA, Kannel WB, Levy D. Hemodynamic patterns of age-related changes in blood pressure. The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1997;96:308–315. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.1.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagberg JM, Seals DR. Exercise training and hypertension. Acta Med Scand Suppl. 1986;711:131–136. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1986.tb08941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeldtke RD, Cilmi KM. Effects of aging on catecholamine metabolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1985;60:479–484. doi: 10.1210/jcem-60-3-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloszy JO, Schechtman KB. Interaction between exercise and food restriction: effects on longevity of male rats. J Appl Physiol. 1991;70:1529–1535. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.70.4.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloszy JO, Smith EK, Vining M, Adams S. Effect of voluntary exercise on longevity of rats. J Appl Physiol. 1985;59:826–831. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1985.59.3.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel A, Stromberg C, Tsutsumi K, Garrido MR, Torres M, Saavedra JM. Angiotensin II receptor subtypes and phosphoinositide hydrolysis in rat adrenal medulla. Brain Res Bull. 1995;38:441–446. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(95)02011-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Sato A, Sato Y, Suzuki H. Increases in adrenal catecholamine secretion and adrenal sympathetic nerve unitary activities with aging in rats. Neurosci Lett. 1986;69:263–268. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(86)90491-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jezova M, Armando I, Bregonzio C, Yu ZX, Qian S, Ferrans VJ, Imboden H, Saavedra JM. Angiotensin II AT(1) and AT(2) receptors contribute to maintain basal adrenomedullary norepinephrine synthesis and tyrosine hydroxylase transcription. Endocrinology. 2003;144:2092–2101. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judge S, Jang YM, Smith A, Selman C, Phillips T, Speakman JR, Hagen T, Leeuwenburgh C. Exercise by lifelong voluntary wheel running reduces subsarcolemmal and interfibrillar mitochondrial hydrogen peroxide production in the heart. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289:R1564–1572. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00396.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannel WB, Gordan T. Evaluation of cardiovascular risk in the elderly: the Framingham study. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1978;54:573–591. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedzierski W, Porter JC. Quantitative study of tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA in catecholaminergic neurons and adrenals during development and aging. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1990;7:45–51. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(90)90072-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livett BG, Marley PD. Noncholinergic control of adrenal catecholamine secretion. J Anat. 1993;183(Pt 2):277–289. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarter RJ, Shimokawa I, Ikeno Y, Higami Y, Hubbard GB, Yu BP, McMahan CA. Physical activity as a factor in the action of dietary restriction on aging: effects in Fischer 344 rats. Aging (Milano) 1997;9:73–79. doi: 10.1007/BF03340130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHenry PL, Ellestad MH, Fletcher GF, Froelicher V, Hartley H, Mitchell JH, Froelicher ESS. A position for health professionals by the committee on exercise and cardiac rehabilitation of the council on clinical cardiology, American Heart Association, Special Report. Circulation. 1990;81:396–398. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.81.1.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moraska A, Deak T, Spencer RL, Roth D, Fleshner M. Treadmill running produces both positive and negative physiological adaptations in Sprague-Dawley rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;279:R1321–1329. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.4.R1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group Report on Hypertension in the Elderly. Hypertension. 1994;23:275–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reymond MJ, Arita J, Dudley CA, Moss RL, Porter JC. Dopaminergic neurons in the mediobasal hypothalamus of old rats: evidence for decreased affinity of tyrosine hydroxylase for substrate and cofactor. Brain Res. 1984;304:215–223. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90324-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabban EL, Hebert MA, Liu X, Nankova B, Serova L. Differential effects of stress on gene transcription factors in catecholaminergic systems. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004a;1032:130–140. doi: 10.1196/annals.1314.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabban EL, Kvetnansky R. Stress-triggered activation of gene expression in catecholaminergic systems: dynamics of transcriptional events. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:91–98. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01687-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabban EL, Nankova BB, Serova LI, Kvetnansky R, Liu X. Molecular regulation of gene expression of catecholamine biosynthetic enzymes by stress: sympathetic ganglia versus adrenal medulla. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004b;1018:370–377. doi: 10.1196/annals.1296.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seals DR, Dinenno FA. Collateral damage: cardiovascular consequences of chronic sympathetic activation with human aging. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H1895–1905. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00486.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seals DR, Taylor JA, Ng AV, Esler MD. Exercise and aging: autonomic control of the circulation. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1994;26:568–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo AY, Hofer T, Sung B, Judge S, Chung HY, Leeuwenburgh C. Hepatic oxidative stress during aging: effects of 8% long-term calorie restriction and lifelong exercise. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:529–538. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speakman JR. Doubly Labelled Water, Theory and Practice. Chapman & Hall; London: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Speakman JR. The history and theory of the doubly labeled water technique. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68:932S–938S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.4.932S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stachowiak MK, Jiang HK, Poisner AM, Tuominen RK, Hong JS. Short and long term regulation of catecholamine biosynthetic enzymes by angiotensin in cultured adrenal medullary cells. Molecular mechanisms and nature of second messenger systems. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:4694–4702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takekoshi K, Ishii K, Isobe K, Nanmoku T, Kawakami Y, Nakai T. Angiotensin-II subtype 2 receptor agonist (CGP-42112) inhibits catecholamine biosynthesis in cultured porcine adrenal medullary chromaffin cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;272:544–550. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takekoshi K, Ishii K, Shibuya S, Kawakami Y, Isobe K, Nakai T. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor counter-regulates type 1 receptor in catecholamine synthesis in cultured porcine adrenal medullary chromaffin cells. Hypertension. 2002;39:142–148. doi: 10.1161/hy1201.096816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tipton CM. Exercise training for the treatment of hypertension: a review. Clin J Sport Med. 1999;9:104. doi: 10.1097/00042752-199904000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuck ML, Armbrecht JA, Coe R, Wongsurawat N. Endocrinology of Aging. Springer-Verlag; 1989. pp. 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Tumer N, Broxson CS, LaRochelle JS, Scarpace PJ. Induction of tyrosine hydroxylase and neuropeptide Y by carbachol: modulation with age. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54:B418–423. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.10.b418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumer N, Demirel HA, Serova L, Sabban EL, Broxson CS, Powers SK. Gene expression of catecholamine biosynthetic enzymes following exercise: modulation by age. Neuroscience. 2001;103:703–711. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumer N, Hale C, Lawler J, Strong R. Modulation of tyrosine hydroxylase gene expression in the rat adrenal gland by exercise: effects of age. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1992;14:51–56. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(92)90009-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumer N, Larochelle JS. Tyrosine hydroxylase expression in rat adrenal medulla: influence of age and cold. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1995;51:775–780. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)00030-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumer N, LaRochelle JS, Yurekli M. Exercise training reverses the age-related decline in tyrosine hydroxylase expression in rat hypothalamus. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1997a;52:B255–259. doi: 10.1093/gerona/52a.5.b255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumer N, Scarpace PJ, Baker HV, Larochelle JS. AP-1 transcription factor binding activity in rat adrenal medulla and hypothalamus with age and cold exposure. Neuropharmacology. 1997b;36:1065–1069. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00093-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voogt JL, Arbogast LA, Quadri SK, Andrews G. Tyrosine hydroxylase messenger RNA in the hypothalamus, substantia nigra and adrenal medulla of old female rats. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1990;8:55–62. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(90)90009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong PC, Hart SD, Zaspel AM, Chiu AT, Ardecky RJ, Smith RD, Timmermans PB. Functional studies of nonpeptide angiotensin II receptor subtype-specific ligands: DuP 753 (AII-1) and PD123177 (AII-2) J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;255:584–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler MG, Lake CR, Kopin IJ. Plasma noradrenaline increases with age. Nature. 1976;261:333–335. doi: 10.1038/261333a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]