Abstract

Dendritic cells (DCs), important early targets of Ebola virus (EBOV) infection in vivo, are activated by Ebola virus-like particles (VLPs). To better understand this phenomenon, we have systematically assessed the response of DCs to VLPs of different compositions. VLPs containing the viral matrix protein (VP40) and the viral glycoprotein (GP), were found to induce a proinflammatory response highly similar to a prototypical DC activator, LPS. This response included the production of several proinflammatory cytokines, activation of numerous transcription factors including NF-kappaB, the functional importance of which was demonstrated by employing inhibitors of NF-kappaB activation, and activation of ERK1/2 MAP kinase. In contrast, VLPs constituted with a mutant GP lacking the heavily glycosylated mucin domain showed impaired NF-kappaB and Erk activation and induced less DC cytokine production. We conclude that the GP mucin domain is required for VLPs to stimulate human dendritic cells through NF-kappaB and MAPK signaling pathways.

Introduction

Marburg and Ebola viruses are members of the family Filoviridae and are the etiologic agents of severe hemorrhagic fever in infected humans. The recent outbreak of Marburg hemorrhagic fever in Angola, West Africa that caused over 200 deaths with a mortality rate approximating 90% underscores the severity of filovirus infection . Ebola virus (EBOV) infections are also associated with a high mortality rate that ranges from 40 to 90% (Mahanty and Bray, 2004). Although human infections have occurred sporadically, the extreme virulence of these viruses magnifies their importance as emerging pathogens and potential bioweapons.

Infection with the Zaire EBOV causes a rapid hemorrhagic fever that can result in death within the second week after the onset of symptoms (Mahanty and Bray, 2004). Several observations suggest an association between a nonfatal outcome after filovirus infection and the development of an effective adaptive immune response. For example, fatal cases of EBOV hemorrhagic fever (EHF) show signs of an impaired immune response (Bray and Geisbert, 2005; Hoenen et al., 2006), lacking the development of a cellular immune response (Sanchez et al., 2004) and in comparison with nonfatal cases, demonstrating little or no circulating antibodies against the virus (Baize et al., 1999). Thus, a rapid and effective adaptive immune response may be required for recovery. Data also suggest that a strong well regulated innate inflammatory response is associated with a better outcome after EBOV infection (Baize et al., 2002; Leroy et al., 2000). Antigen presenting cells such as DCs and macrophages that act as a vital link between the early innate and later adaptive immune response (Reis e Sousa, 2004) serve as early targets of EBOV infection in vivo (Geisbert et al., 2003) and likely play a prominent role in the pathogenesis of EHF (Bray and Geisbert, 2005). These observations are thus consistent with the idea that the earliest interactions of the virus with the innate immune response influence the outcome of disease.

Ebola virus-like particles (VLPs) have been used for the study of early EBOV-host cell interactions. EBOV VLPs can be generated by expression of VP40, the matrix protein of the EBOV, and, co-expression of EBOV glycoprotein (GP) with VP40 yields VLPs that contain GP on their surface (Jasenosky et al., 2001; Timmins et al., 2001). In contrast to infection with EBOV, Ebola VLPs comprised of VP40 and GP were previously shown to stimulate both macrophages and DCs (Bosio et al., 2004; Wahl-Jensen et al., 2005a), and based on this capacity, the VLPs have been proposed as vaccines against filoviruses (Warfield et al., 2003; Ye et al., 2006). Although it is unclear how VLPs, which lack viral genetic material and therefore cannot productively replicate, trigger this activation; the interaction of Ebola VLPs with DCs will likely mimic the initial interaction of DCs with infectious EBOV.

In this study, EBOV VLPs were employed to identify early dendritic cell responses to virus infection. We have (1) carefully characterized which VLP components contribute to the activation and (2) defined the signaling pathways activated by the VLPs. Our results suggest that VLPs are similar but not identical to a prototypical activator of DCs, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), in their capacity to induce cytokine production, activate cellular transcription factors and to activate NF-κB and MAP kinase signaling pathways. They also demonstrate that NF-κB activation plays a critical role in both VLP and LPS induced DC activation and that full activation of DCs requires that the GP on the surface of the VLPs possess an intact carbohydrate-rich mucin domain. These data therefore define mucin domain-dependent signaling pathways that likely contribute to EBOV pathogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Cells, plasmids and antibodies

293T (human embryonic kidney) cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Invitrogen), 2 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen), 100 units/ml of penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37°C in 7% CO2. All Ebola viral genes kindly provided by Viktor Volchkov (INSERM, Lyon) and Elke Mühlberger (Marburg University, Marburg) were sequenced and confirmed to correspond to the published Zaire EBOV strain Mayinga sequences. EBOV VP40 was expressed using the pCDNA3 or pCAGGS vector while all the other EBOV proteins were expressed using pCDNA3. The GPΔmucin gene was constructed as previously described (Manicassamy et al., 2005). Antibodies used in these studies include anti-p38, -phosphop38, -ERK1/2, -phosphoERK1/2, -SAPK/JNK, -phosphoSAPK/JNK (cell signaling technology, Danvers, MA), anti-cd11c, -CD14,-HLA-DR (BD Pharmingen, Franklin Lakes, NJ), anti-VP40 was a kind gift from Ronald Harty (University of Pennsylvania), anti-VP24 was a kind gift from Victor Volchkov (INSERM), anti-VP35, anti-GP and anti-NP were developed in collaboration with the Hybridoma Center located in the Mount Sinai Department of Microbiology, neutralizing anti-GP1 (AZ52) was a kind gift from Erica Ollmann Saphire (The Scripps Research Institute), anti-tubulin, anti-mouse, anti-human and rabbit IgG (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), anti-IκBα (Epitomics, Burlingame, CA).

VLP production

VLPs were produced by transfecting 3 μg of expression plasmids into 1.5×106 293T cells in six-well dishes and by transfecting 18 μg of expression plasmids into 107 293Ts in 10 cm plates. The EBOV Zaire VP40 expression plasmid was transfected alone or in combinations with EBOV Zaire GP, NP, VP24, VP30 and VP35 expression plasmids at equal DNA concentrations. Furthermore, to visualize fluorescent VLPs, a VP40-GFP (VP40 was cloned in frame at the N-terminus of VP40) chimeric protein was expressed from the expression plasmid pCAGGS. This protein could produce VLPs as determined by western blotting, fluorescent microscopy and electron microscopy (not shown). Transfections were performed using lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) at a 1:1 ratio of DNA to lipofectamine following the manufacturer's protocol. When VLPs were produced for silver staining, media was replaced 12−16 hours after 293T transfection with VP-serum free media (Invitrogen). 48 hours post-transfection, cells and cellular debris were pelleted away from the harvested VLP-containing supernatant with a cell spin. Then, VLPs were centrifuged through a sucrose cushion at 26 000 rpm in an SW-28 rotor for 2 hours at 4°C, washed in ice-cold NTE buffer (10 mM Tris pH7.5, 100mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA) by centrifuging at 26 000 rpm for 2 hours at 4°C and then gently tapped 100 times to resuspend in 50−100 μL of NTE buffer. VLP protein content was quantitated using the DC protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). VLPs were left on ice for up to 48 hours until used. VLP preparations contained < 0.03 IU (endotoxin units) per microgram of total protein as determined by the Limilus Amebocyte Lysate assay (Cambrex, Walkersville, MD).

Electron Microscopy

10 μL of VLPs were pipetted onto 300 mesh copper grid coated with carbon film and incubated for 15 minutes at RT. Grids were then washed twice with water and negatively stained for 15 seconds using 1% phosphotungstic acid buffered to pH 7.0 with 1M ammonium hydroxide. Particles were then visualized using a Hitachi H7000 transmission electron microscope.

Silver Staining

∼ 1 μg of serum-free VLPs (see VLP production) were loaded onto 4−20% gradient gels and proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Silver staining was performed using SilverQuest silver staining kit (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's protocol with the exception that half the reagent volumes were used per assay.

Isolation and culture of human DCs

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by Ficoll density gradient centrifugation (Histopaque; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) from buffy coats of healthy human donors (New York Blood Center). CD14+ cells were immunomagnetically purified using anti-human CD14 antibody-labeled magnetic beads and iron-based Midimacs LS columns (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). After elution from the columns, cells were plated (0.7−1×106 cells/ml) in RPMI (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 2% human serum AB (GemCell, Gemini Bio-Products, West Sacramento, CA), 100 units/ml of penicillin, 100 g/ml streptomycin, 55μM β-mercaptoethanol, 500 U/ml human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF; Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ), 500 U/ml human interleukin-4 (IL-4; Peprotech), 1ng/mL ciproflaxocin (SIGMA) and incubated for 5 to 7 days at 37°C.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed in a Cytomic FC500 Coulter station (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL). Data were analyzed using WinMDI Version 2.8 (http://facs.scripps.edu/software.html).

DC stimulation

DCs plated in 96 well dishes (9×104 cells/well) or 24 well dishes (0.5×106 cells/well) were stimulated with 10−20μg/mL VLP, 50ng/mL TNFα or 10−100ng/mL LPS (Salmonella Minnesota R595; Alexis, San Diego, CA) for the indicated amount of time in RPMI (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 1% human serum AB (GemCell), 100 units/ml of penicillin, 100 g/ml streptomycin, 55μM β-mercaptoethanol. Supernatants were tested for cytokine production, while harvested DCs were tested for MAPK and TF activation.

IL-6 and IL-8 ELISA

IL-6 and IL-8 was detected from supernatants collected 12−24 hours post stimulation using capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The IL-6 and IL-8 ELISAs were performed according to the manufacturer's protocol (eBioscience, San Diego, CA and BD Pharmingen, Franklin Lakes, NJ, respectively). Briefly for the IL-6 ELISA, 96 well flat-bottomed Maxi-Sorp (Nunc, Rochester, NY) plates were used for capture antibody coating and subsequent IL-6 detection. Coated plates were washed three times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T) and blocked with PBS + 10% FCS (PBS-F) at room temperature (RT) for 1 hour. Plates were washed three times with PBS-T, supernatants added and incubated for 2 hours at RT followed by five washes. Detection and HRP conjugated streptavidin antibody incubations (1 hour at RT) were separated by five washes. After a final seven washes, TMB substrate was added to each well and incubated for 15 minutes in the dark until the HRP reaction was stopped with ¼ volume of 1N HCl. Plates were read using an ELISA plate reader (Biotek Instruments, Winooski, VT) at 450nm wavelength.

GP ELISA

Mock VLPs and VLPs (with or without GP) were adsorbed overnight onto Maxi-Sorp 96 well ELISA plates (Nunc) in coating buffer (0.05 M carbonate-bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.6) supplemented with 0.1% Triton X-100. Plates were washed three times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T) and blocked with PBS + 10% FCS (PBS-F) at RT for 1 hour. Plates were washed three times with PBS-T. Detection (AZ52 anti-GP antibody) and HRP conjugated anti-human IgG antibody incubations (1 hour at RT) were separated by five washes. After a final seven washes, TMB substrate was added to each well and incubated for 15 minutes in the dark until the HRP reaction was stopped with ¼ volume of 1N HCl. Plates were read using an ELISA plate reader (Biotek Instruments, Winooski, VT) at 450nm wavelength.

NF-κB Inhibition and Cytotoxicity Assays

DCs plated in 96 well dishes (9×104 cells/well) in RPMI containing 1% human serum were pretreated 15 minutes with inhibitor SN50 and control peptide SN50M at final concentration of 66 μg/mL or one hour with IKK2 inhibitor (IKK IV) at a final concentration 2.5 μM (Calbiochem, EMD Biosciences, San Diego, CA). Spent media from 1% Triton X-100 or VLP- treated DCs (12−16 hours) was tested for the presence of IL-6 and lactate dehydrogenase. Amounts of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) were assayed using a Cytotoxicity Detection Kit (LDH) (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) following the manufacturer's protocol. 100% cytotoxicity was determined using the amount of LDH released into the media from DCs treated with 1% Triton X-100.

Multiplex Cytokine Measurements

50 μL of the stimulated DC spent media was tested for the presence of 22 human cytokines using Beadlyte® Human 22-Plex Multi-Cytokine Detection System (Upstate, Billerica, MA) following the manufacturer's protocol. Plates were read in a Luminex plate reader, and data were analyzed using software from Applied Cytometry Systems (Sacramento, CA).

Nuclear extraction

Stimulated DCs were snap-frozen in a dry-ice ethanol bath. Nuclear extractions were performed using nuclear extraction kit (Panomics, Fremont, CA) following the manufacturer's protocol with the exception that the final resuspension volume was 30 μL. Protein content in nuclear extracts was then quantitated using the DC protein assay (Bio-Rad).

Transcription Factor Array

Nuclear extractions (see above) were performed on untreated DCs and DCs treated for 10 and 30 minutes with VLPs and LPS. Equivalent nuclear protein concentrations (total of 7.5 μg) were used in the Protein/ DNA array I (Panomics, Fremont, CA) to determine transcription factor (TF) activity following the manufacturer's protocol. Very briefly, biotin-labeled probes (TransSignal Probe Mix) were added to nuclear extracts and incubated for 30 minutes at 15°C. This allowed activated TFs to bind probes forming a complex. After uncomplexed probes were washed away using spin columns, the protein/DNA complexes were disassociated. The column eluate containing freed labeled probes was incubated with membranes spotted with the probe complements. The hybridized spotted membranes were then washed, incubated with streptavidin-HRPO, washed again and developed by chemiluminescense. Each transcription factor is represented by a pair of duplicate spots on the array. One duplicate set being a dilution of the other set. Arrays were developed using several exposure times in order to avoid signal saturation. At each exposure, films of the arrays were scanned and the intensity of spots quantitated using ImageQuant software. The average signal of duplicate spots was then obtained. If duplicate spots varied more than 25%, they were eliminated from the analyses. In order to compare the transcription factor signal from one membrane (sample) to the control (untreated DCs), signals were normalized by dividing the sample signal with the signal of an unchanged TF (selected from that specific exposure). To be more stringent, signals were normalized against two TFs. According to the manufacturer, >2 fold changes in signal are deemed to be significant. We chose to deem significant those signals (i.e. NF-κB) that had a greater than 2 fold difference as compared to the control when normalized against both normalizing TFs. Moreover, almost all transcription factors found to be activated at the 10 minute mark were also found to be significantly altered at the 30 minute time point as compared to control. Therefore, the 10 and 30 minute arrays reinforced the credibility of the transcription factors found to be up or down-regulated. In a few exceptional cases, TFs were upregulated at only one of the two time points, as highlighted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Stimulated DC transcription factors.1

| TF binding | Not detected | Unchanged or <2 fold change | Increased (>2 fold) | Increased (LPS only) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transcription Factors | GATA | EGR | NF-κB | Smad3/4 |

| NFATc | CREB | E2F-1 | ||

| SRE | SP1 | GRE | ||

| PRE | PPAR | NF-E1 | ||

| IRF-1 | RAR(DR5) | USF-1 | ||

| STAT-5 | C/EBP | Ets | ||

| Ets/PEA3 | FAST-1 | |||

| p53 | NF-1 | |||

| Myc -Max | Pbx-1 | |||

| C-Myb | 2STAT-1 | |||

| GAS/ISRE | 2STAT-3 | |||

| TFIID | 3CBP | |||

| AP-2 | 4STAT-6 | |||

| 5SIE | ||||

| 5TR(DR4) | ||||

| 6STAT-4 |

Shown in table is the relative induction of transcription factor binding after LPS and VLP stimulation as compared to control (untreated DCs). Differences in TF binding induction between LPS and VLP noted below table.

STAT-1 and STAT-3 activity was detected after VLP and LPS treatment, but was undetectable in unstimulated DCs

CBP activity was downregulated by VLPs after 10 minutes, but was upregulated in LPS treated DCs

STAT-6 activity was upregulated by VLPs, but was only upregulated by LPS after 30 minutes.

Both SIE and TR(DR4) were upregulated by VLPs after 10 minutes, but at 30 minutes both were comparable to control

STAT-4 activity was upregulated by VLPs, but was only upregulated by LPS after 30 minutes.

Western blot

After the indicated time points of DC stimulation, 5×105 DCs/stimuli were harvested, pelleted and snap-frozen in a dry-ice ethanol bath and stored at −80°C. Cell pellets were thawed on ice, resuspended in 50μL of 1X protein sample buffer, sonicated and loaded into a 4−20% gradient or 10% gels for separation by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane, blocked in 1% milk in TBS (50mM Tris pH 7.5, 100mM NaCL) for one hour, probed overnight with appropriate antibodies diluted in 0.5% milk in TBS, washed 3 times in TBS-T (TBS + 0.075% tween-20) for 5 minutes/wash, probed with secondary antibody for 1 hour and washed a final 3 times. The Western blots were developed using the Western Lightning ECL kit (Perkin-Elmer, Boston, MA) and Kodak BioMax film (Kodak, Rochester, NY).

Flow cytometry

DCs were incubated with GFP-VP40 induced VLPs for 30 minutes at 37°C and washed twice with PBS. Cells were then stained with an anti-CD11c (Pharmingen) for 30 minutes at 0°C and washed again. FACS was performed using a Cytomics F500 machine (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) and then analyzed using Win MDI 2.8 software.

Results

Incorporation of EBOV proteins into VLPs

In order to accurately define how VLPs affect DCs, we first systematically characterized VLPs produced in 293T cells with respect to their biochemical make-up and morphology. Over-expression of the VP40 protein is sufficient to produce EBOV VLPs which bud from transfected cells (Jasenosky et al., 2001; Timmins et al., 2001). Moreover, co expression of additional virus proteins such as GP, results in their incorporation into the VLPs (Noda et al., 2002). We generated Ebola VLPs by transfection of 293T cells with plasmids expressing VP40, VP40 and GP or a combination of VP40, VP35, VP24, VP30, NP and GP (“complete” or cVLP). Supernatants were harvested from the mock or expression-plasmid transfected 293T cells, and the VLPs within the supernatant were purified through a sucrose cushion, washed, resuspended and quantitated for protein content. To determine their content and morphological characteristics, purified VLPs were subjected to western blotting, electron microscopy and silver staining (Fig. 1).

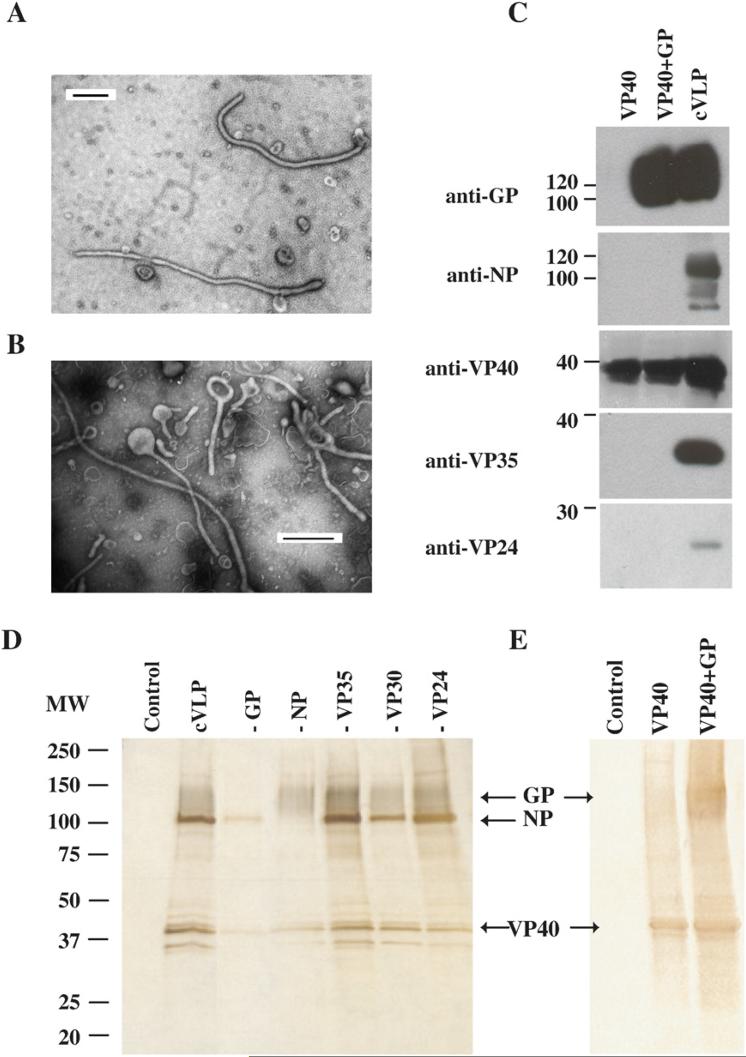

Figure 1. Morphology and composition of VLPs.

VLPs were prepared by expressing 1) VP40, 2) VP40 and GP and 3) VP40, VP24, VP35, VP30, NP and GP (cVLPs). A, B) VLPs were negatively stained and observed by electron microscopy. Shown in A) is an example of VLP filovirus morphology. A representative VLP picture shown in B) demonstrates the pleimorphic morphology of all the VLP preparations. All line bars represent a length of 500nm. C) Western blot analyses of purified VLP preparations using antibodies against EBOV proteins GP, NP, VP40, VP35 and VP24. D) Silver stains were performed on SDS-PAGE-separated purified VLPs. The first lane, marked control, shows the contents of mock VLPs. In the second lane is an example of the proteins found in cVLPs. Each of the next lanes shows the contents of cVLPs produced with exclusion of a single EBOV protein (protein excluded indicated above lane). Labeled arrows point to the indicated EBOV proteins. E) Shows silver stain of mock, VP40 and VP40+GP VLPs.

When VLP samples were negative-stained and visualized using an electron microscope, all samples, with the exception of “mock” (not shown), demonstrated filamentous filovirus-like morphology (Fig. 1A). Moreover, a representative example shows that the VLPs are pleimorphic (Fig. 1B). Thus, the size and morphological characteristics of the VLPs are similar to those exhibited by EBOV (Geisbert and Jahrling, 1995). Equivalent amounts of VLP protein, except for mock-transfected samples that contained little protein, were separated by SDS-PAGE, blotted and examined using anti-VP40, VP24, VP35, NP and GP monoclonal antibodies. The presence of VP30 was not determined since specific antibodies against VP30 were not readily available. VP40 was detected in all VLP preparations (Fig. 1C). A ∼125 kDa form of GP was detected in VP40+GP and cVLPs. VP35, VP24, and NP were detected in the VLPs produced from the 293T cells transfected with a combination of all proteins (cVLP), but not in the samples that contained only VP40 or VP40+GP (Fig. 1C). The presence of GP in the VLPs was also documented by silver staining (Fig. 1D and E), electron microscopy, where VLPs appeared to a have GP- decorated surface (data not shown), and by ELISA, using a neutralizing monoclonal antibody against GP1 (KZ52, (Maruyama et al., 1999)) (data not shown).

To determine the relative contribution of each EBOV protein to the contents of the VLPs, VLPs produced from 293T cells were analyzed by SDS PAGE and silver staining. Fig. 1D lane cVLP shows the silver stained proteins from cVLPs. To identify these proteins, individual components of the VLPs were excluded from each transfection, with the exception of VP40 since it is required for efficient VLP production (Fig. 1D lanes –GP, -NP, -VP35, -VP30, -VP24). The exclusion of GP produced a silver stain that lacked a smear from 110−150 kDa (see lane -GP) present in other lanes while exclusion of the NP protein lacked the sharp band found at ∼105 kDa. This banding pattern is consistent with the expected sizes of the glycosylated GP and NP EBOV proteins (Fig. 1C), respectively. It is interesting to note that bands appeared at approximately 35 kDa, but exclusion of VP35 failed to eliminate these bands (Fig. 1D, lane – VP35). Therefore, although VP24 and VP35 were present within VLPs (Fig. 1C), their contribution to the final cVLP was minimal. In Fig. 1E, VP40, VP40+GP VLPs were silver stained. A smear is present in the VP40+GP VLP that corresponds to the expected size of GP and a ∼40kDa band is present in VP40 and VP40+GP lanes (Fig. 1E) which would correspond to the expected size of VP40.

VP40+GP VLPs are sufficient to efficiently stimulate DC secretion of inflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-8, TNFα, MIP-1α, IL-12p40, RANTES and IP-10

Having demonstrated that VLPs containing different viral components could be reproducibly generated, we next asked whether different VLP preparations have different capacities to stimulate DCs. Day 5−7 monocyte-derived immature DCs that expressed no CD14, low MHCII, and high CD11c on their cell surface (not shown) were used in these and subsequent experiments. Equivalent protein concentrations of VLPs (10μg/mL) were added to DCs. We used 10μg/mL of VLPs, also used previously to stimulate DCs (Bosio et al., 2004), because it was subsaturating for cytokine production (not shown). Twenty four hours post-treatment spent supernatant was tested for the presence of IL-8, a marker of DC stimulation. As depicted in fig. 2A, DCs treated for 24 hours with LPS (10 ng/mL), VP40+GP and cVLPs, secreted similar levels of IL-8 (∼2000−2500 pg/mL) while VP40 VLPs secreted less (∼400 pg/mL). This experiment was repeated two more times and showed similar results when supernatants were tested for the presence of both IL-8 and IL-6. It should be noted that although the absolute amounts of cytokine varied from experiment to experiment, possibly due to differences in DCs derived from different donors, the trends remained the same. These results are consistent with other studies that demonstrated that VP40+GP VLPs could more efficiently stimulate human DCs than VLPs that lacked GP (Wahl-Jensen et al., 2005a; Ye et al., 2006). To exclude the possibility that the VLPs were contaminated with LPS, VP40+GP VLPs and LPS were boiled for 1 hour. The resulting samples were then used to stimulate DCs. In the case of LPS, boiling did not inhibit or enhance LPS mediated DC cytokine secretion (not shown). However, as previously shown (Bosio et al., 2004), boiling of the Ebola VLPs abolished their ability to stimulate DCs (not shown). These results suggest that GP makes a major contribution to the stimulatory function of the VLPs while no effect of the internal components NP, VP35 and VP24 were detectable.

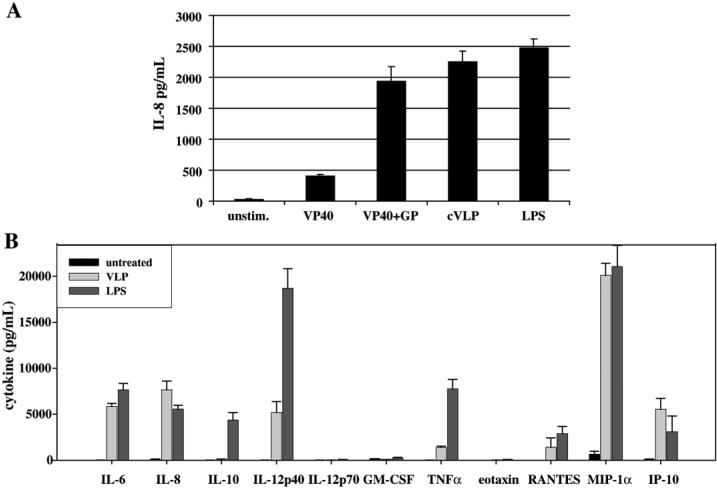

Figure 2. VP40+GP VLPs are sufficient to efficiently stimulate DC secretion of inflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-8, TNFα, MIP-1α, IL-12p40, RANTES and IP-10.

A) Equivalent protein concentrations (10 μg/mL) of VP40, VP40+GP and cVLPs along with LPS (10 ng/mL) were added to DCs. Spent media, harvested 24 hours post-treatment, was tested for the presence of IL-8. B) Mock, VP40+GP and LPS were used to stimulate DCs for 16−18 hours. Spent supernatant was tested for the presence of 22 cytokines listed in Table 1. A select number of cytokines are shown, including all cytokines present at levels >200pg/mL from VLP-stimulated DC supernatants.

To further define the DC signaling pathways induced by VLPs, the cytokine profiles in the supernatants of VLP stimulated DCs were compared to the cytokine profile of a well characterized inflammatory inducer, LPS. A complete list of the cytokines included in this multiplex analysis is provided in Table 1. Those cytokines not highlighted in Table 1 were either not detected or were detected below 200 pg/mL in the supernatants of DCs stimulated with VLPs. Cytokines secreted by DCs stimulated by VLPs (highlighted with bold text in Table 1) as well as those stimulated by LPS are shown in fig. 2B.

Table 1.

Cytokines detected in VLP-stimulated DC supernatants1.

| IL-1α | IL-12p70 |

| IL-1β | IL-13 |

| IL-2 | IL-15 |

| IL-3 | GM-CSF |

| IL-4 | IFN-γ |

| IL-5 | TNFα |

| IL-6 | EOTAXIN |

| IL-7 | MCP-12 |

| IL-8 | RANTES |

| IL-10 | MIP-1α |

| IL-12p40 | IP-10 |

VLP-stimulated DC supernatants were tested for the presence of the cytokines shown in the table. Cytokines present at quantities above 200 pg/mL are shown in bold and in fig. 2B were compared to levels secreted by LPS-stimulated DCs.

MCP-1 was present in supernatant of unstimulated DCs.

VLP (VP40+GP)-stimulated DCs secreted IL-6, IL-8, MIP-1α, RANTES and IP-10 at levels that were comparable to those secreted by LPS-stimulated DCs (Fig. 2B). Although VP40+GP VLPs stimulated many of the same cytokines as LPS, TNFα, IL-12p40 and IL-10 were secreted at relatively higher levels by LPS-stimulated DCs. Nevertheless, the similar pattern of cytokines secretion induced by LPS and VLPs suggested that the two stimuli activate at least partially overlapping signaling pathways.

VLPs induce IL-6 production through an NF-κB dependent pathway

RANTES, TNFα, IL-6, MIP-1α and IL-8 are regulated by the NF-κB signaling pathway (reviewed in (Ali and Mann, 2004)). Therefore, we compared the kinetics of induction of NF-κB in DCs treated with VP40+GP VLPs (10μg/mL), with LPS (10ng/mL) or with TNFα (50ng/mL). Total dendritic cell lysates were generated and subjected to western blotting for IκBα (Fig. 3A). NF-κB is held in the cytoplasm by IκB proteins, including IκBα. Upon stimulation by ligands that induce NF-κB via the classical pathway (for example by LPS or TNFα), IκBα is phosphorylated and subsequently degraded releasing NF-κB which translocates to the nucleus and activates transcription of a variety of genes, including the IκBα gene. Fig. 3A shows that TNFα and LPS treatment of DCs induces IκBα degradation within 10 minutes. However, VLP treatment induces a significant decrease in IκBα levels only after 30 minutes. While the LPS and VLP induced a reduction in IκBα that lasted at least up to 1 hour, the TNFα reduction in IκBα lasted up to 30 minutes, but basal IkBα levels were restored by 1 hour. This suggested that the NF-κB activating signal induced by VLPs had different kinetics than the NF-κB signal induced by LPS.

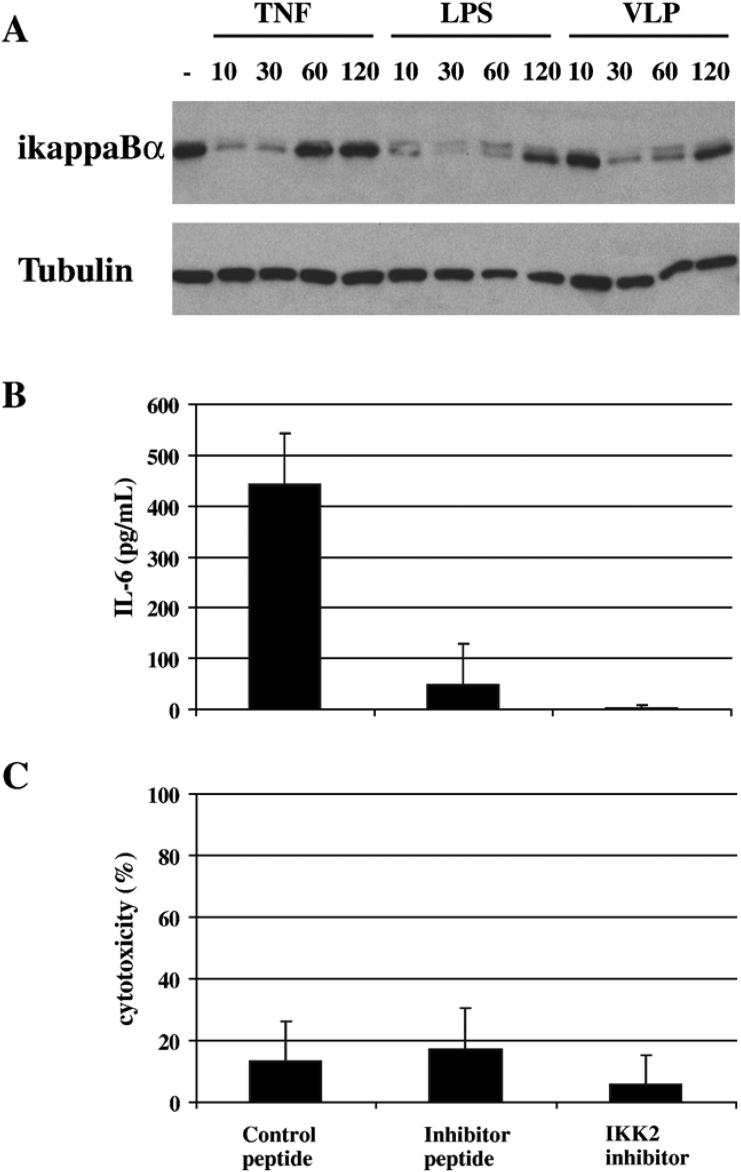

Figure 3. VLPs induce IL-6 production through NF-κB.

A) DCs treated with TNFα (50ng/mL), LPS (10ng/mL) and VP40+GP VLPs (10μg/mL) for 10, 30, 60 and 120 minutes were harvested and total cell lysates (∼105 cellular equivalents/ lane) tested for the presence of IκBα and the loading control tubulin by western blotting. B, C) DCs were pretreated for 15 minutes with SN50 NF-κB inhibitor and control peptide and 1 hour with IKK2 inhibitor. Then DCs were treated with VLPs for 12−16 hours and spent media tested for the presence of B) IL-6 and C) lactate dehydrogenase. In C) 100% represents the amount of lactate dehydrogenase released into the media from DCs treated with 1% Triton X-100.

To determine if signaling through NF-κB is important for the secretion of a representative cytokine (IL-6) that is produced by VLP-stimulated DCs, DCs were pretreated with NF-κB inhibitors prior to VLP addition (Fig. 3B and 3C). To control for the NF-κB peptide inhibitor, a control peptide was also used to pretreat the DCs. Supernatants from VLP stimulated DCs were tested for the presence of IL-6 (Fig. 3B) or a marker of cell death, lactate dehydrogenase (Fig. 3C). As shown in fig. 3B and C, at concentrations that did not have detectably toxic effects upon cells, the presence of inhibitors but not control peptide profoundly inhibited IL-6 secretion. The peptide inhibitor of NF-κB interferes with NF-κB nuclear translocation, while the IKK2 inhibitor inhibits IKKB, the upstream kinase that phosphorylates IκB. Therefore, activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway contributes in a critical way to VLP activation of DCs.

VLPs activate numerous transcription factors

To further characterize the signaling pathways stimulated by VLPs and LPS, transcription factors activated by either VLP or LPS treatment at 10 and 30 minutes post-addition were identified. Nuclear extracts were generated from harvested DCs, and specific transcription factors were detected using an array of DNA probes (see materials and methods). The strength of transcription factor binding to its oligonucleotide target was then quantified. Signals generated using the nuclear extracts from stimulated DCs were compared to the signals generated by unstimulated DCs. Transcription factor activities were compared, and if there was a downregulation or upregulation of at least two fold, those transcription factors were deemed to have been significantly altered.

By these criteria, a wide variety of transcription factors are activated by VLPs within 10 minutes of stimulation and remain activated through 30 minutes. Table 2 summarizes those transcription factors that were active at both time points with the exceptions stated in the notes. It is important to note that transcription factors may show different strengths of activation when comparing the two time points (10 and 30 minutes), but because the results were not to be interpreted as being strictly quantitative, this is not shown. VLPs were found by this method to activate many of the same transcription factors as LPS. Notably, this array further corroborates the activation of NF-κB seen in fig. 3. However, some differences between the VLP and VLP-treated cells were noted. For example, Smad3/4 was shown to be induced by LPS, but not by VLP stimulation (Table 2).

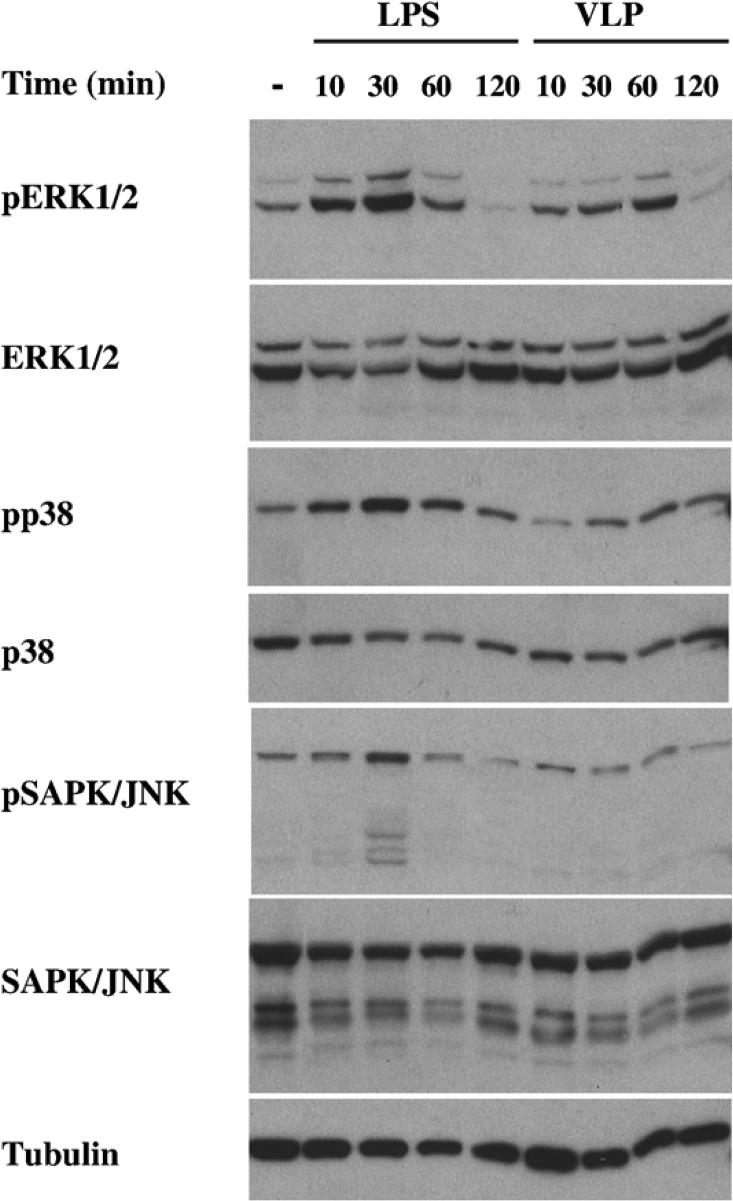

VLPs induce MAPK ERK1/2 signaling

VLP stimulated transcription factors are involved in a variety of processes that include inflammation (NF-κB), proliferation (E2F-1), serum response and cell growth (SIE), hormone response TR (DR4) and stress (Ets). Interestingly, MAPK members phosphorylate and regulate members of the Ets (Sharrocks, 2001), USF (Corre and Galibert, 2005) and STAT (Decker and Kovarik, 2000) transcription factor families. Therefore, we tested extracts of DCs stimulated 10, 30, 60 and 120 minutes with VLP and LPS for the presence of activated ERK1/2, p38 and SAPK/JNK proteins, as evidenced by their phosphorylation. As shown in fig. 4, DCs stimulated with LPS for 10 and 30 minutes showed ERK activation (as indicated by the presence of phosphorylated ERK), while VLPs also induced ERK phosphorylation, but with a different kinetics. ERK phosphorylation after VLP stimulation was seen after 30 minutes of treatment. However, although activation of p38 and SAPK/JNK was seen after 30 minutes of LPS treatment, there was little p38 and no SAPK/JNK phosphorylation seen in VLP stimulated DCs (Fig. 4). Therefore, VLPs activate not only NF-κB but also ERK signaling, following their addition to human DCs.

Figure 4. VLPs activate ERK1/2 in DCs.

DCs treated with LPS (10 ng/mL) and VLP (VP40+GP VLPs (10 μg/mL)) for 10, 30, 60 and 120 minutes were harvested and total cell lysates (∼105 cellular equivalents/ lane) were tested for the presence of phosphorylated ERK1/2 (pERK1/2), total ERK1/2, phosphorylated-p38 (pp38), total p38, phosphorylated-SAPK/JNK (pSAPK/JNK), total SAPK/JNK and tubulin. The same membranes blotted and tested for pERK1/2, pp38 and pSAPK/JNK were stripped and tested for total levels of ERK1/2, p38 and SAPK/JNK, respectively. The membrane western blotted for SAPK/JNK was stripped and tested for levels of tubulin.

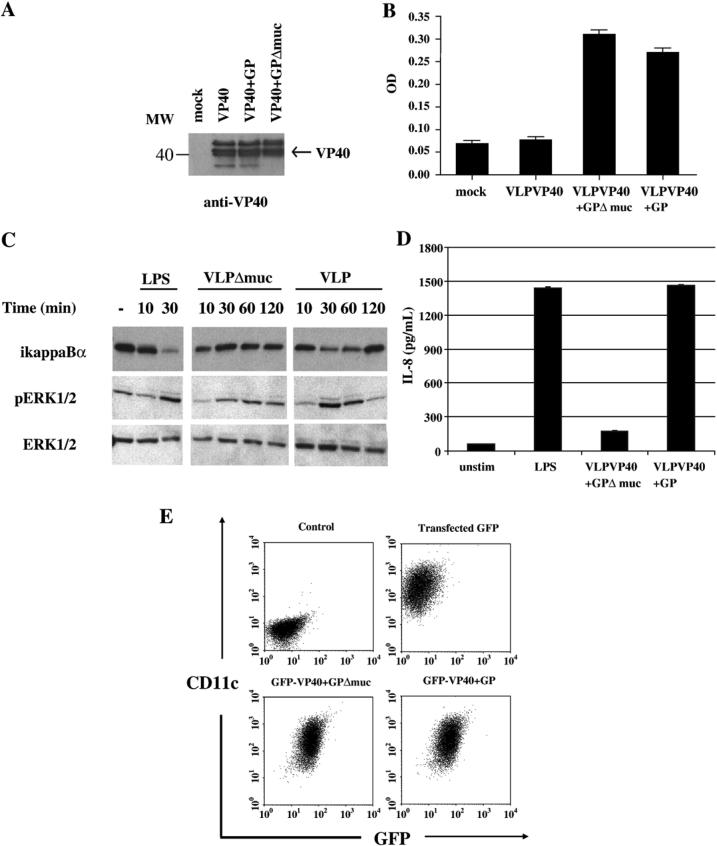

An intact GP mucin domain is required for DC activation

Expression of EBOV GP in human cells can have a profound effect on the phenotype of that cell, and these effects are partly due to the heavily glycosylated mucin domain located in the GP ectodomain (e.g.(Sullivan et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2000)). However, the mucin domain does not appear to be required for GP to mediate cell attachment and entry (Jeffers, Sanders, and Sanchez, 2002; Manicassamy et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2000). To test whether the mucin domain was required for stimulation of DCs, a mucin-deletion GP mutant (Δ309−476) was generated. First we tested whether the GPΔmucin would be incorporated into VLPs. 293T cells were mock, VP40, VP40+GP and VP40+GPΔmucin transfected for 48 hours and the presence of VLPs was tested by western blotting for VP40 after VLP purification. Although mock contained no VP40 protein (see “mock” lane, Fig. 5A), VP40 containing VLPs could be isolated from VP40, VP40+GP and VP40+GPΔmucin transfected 293T supernatants. Therefore, VLP production was not inhibited by the co-expression of the GPΔmucin mutant. Furthermore, electron microscopy performed on the VLPs demonstrated that VP40+GPΔmucin VLPs had a similar morphology toVP40+GP VLPs, including the appearance of a GP-decorated surface (not shown). To test the level of GP incorporation into VLPs, equivalent amounts of VP40, VP40+GP and VP40+GPΔmucin VLPs were subjected to an anti-GP ELISA (Fig. 5B). Mock and VP40 VLPs show equivalent ODs while GP and GPΔmucin containing VLPs demonstrate equivalent ODs. Therefore, similar levels of WT and mutant GP are incorporated into VLPs. Equivalent amounts of GP and GPΔmucin containing VLPs were then used to stimulate DCs (along with LPS control) for 10, 30, 60 and 120 minutes after which DCs were harvested and lysates subjected to western blot analysis for ikappaBα, pERK1/2 and total ERK1/2 (Fig. 5C). The WT VLPs, as previously shown in Figure 5, induced ikappaBα degradation at 30 and 60 minutes whereas a significant decrease in ikappaB was not apparent in cells treated with the VP40+ GPΔmucin VLPs. Further, the moderate increase in ERK phosphorylation was more apparent in the GP wild type containing VLPs as compared to the mutant GP containing VLPs (Fig. 5C). Densitometry analysis on the ikappaBα, phospho ERK and control ERK bands within the western blot confirmed differences in the ratios of ikappaBa and phospho ERK to total ERK between VLPGP and VLPGP Δmucin treated DC lysates (not shown). Equivalent amounts of GP and GPΔmucin containing VLPs were also used to stimulate DCs (along with LPS control) for 20 hours after which supernatants were tested for the presence of IL-8 (Fig. 5D). As shown in Figure 5D, unstimulated DCs secreted relatively low levels of IL-8 similar to those secreted by VLP+GP Δmucin treated DCs, while both LPS and VLP+GP treated DCs secreted approximately ten fold more IL-8 than the unstimulated control. Finally, to confirm that deletion of the mucin domain did not alter the ability of VLPs to associate with DCs, we employed GFP-tagged VLPs. We constructed and expressed a GFP-VP40 chimeric protein. Expression of this stable (not shown) chimeric protein leads to the production of fluorescent VLPs that can incorporate GP and can be visualized by fluorescence microscopy (not shown). Equivalent (15 μg/mL) amounts of GFP-VP40+GP, GFP-VP40+GPΔmuc and mock VLPs (purified from GFP-transfected cells) were incubated with DCs for 30 minutes at 37°C. Cells were then washed and then tested for their association with DCs by flow cytometry. Isotype controls showed no fluorescence (Fig. 5E top left dot plot). CD11c+ cells were associated with equivalent GFP fluorescence when incubated with GFP-VP40+GP and GFP-VP40+GPΔmuc VLPs (Fig. 5E, bottom dot plots) but no GFP fluorescence was seen when DCs were incubated with mock VLPs prepared from GFP transfected 293Ts (Fig. 5E top right dot plot). Cumulatively, these data demonstrate that the mucin domain of GP is not required for association of VLPs with DCs but is required for stimulation of DCs by the VLPs.

Figure 5. VLP GP mucin domain-dependent activation of NFκB and ERK1/2.

A) Western blot analyses of purified VLP preparations using antibody against EBOV protein VP40. B) ELISA, performed on equivalent amounts of VP40, VP40+GP, VP40+GPΔmuc VLPs using an EBOV-neutralizing anti-GP antibody (AZ52). C) Shown is one blot of one representative experiment where equivalent protein concentrations (15 μg/mL) of VP40+GP and VP40+GPΔmuc VLPs and 10 ng/mL of control LPS were used to treat DCs for 10, 30, 60 and 120 minutes and the total cell lysates (∼105 cellular equivalents/ lane) were tested for the presence of IκBα, phosphorylated ERK1/2 (pERK1/2) and total ERK1/2. D) Shown is a representative experiment where equivalent protein concentrations (15 μg/mL) of VP40+GP and VP40+GPΔmuc VLPs and 10 ng/mL of control LPS were used to treat DCs (5×105 cells) for 20 hours and supernatant was tested for levels of IL-8. The control in this experiment is unstimulated DCs (unstim). E) Association of GFP-tagged VLPs with DCs was assayed by flow cytometry. Control (top left dot plot) depicts DCs stained with isotype controls. Equivalent concentrations of (15 μg/mL) GFP-VP40+GP (bottom right dot plot), GFP-VP40+GPΔmuc (bottom left dot plot) and mock VLPs purified from GFP-transfected cells (top right dot plot) were incubated with DCs for 30 minutes at 37°C, washed, stained for the DC marker CD11c and assayed by flow cytometry.

Discussion

Our data identify novel signals triggered by EBOV VLPs within human DCs. These studies provide molecular context to previous observations that EBOV VLPs activate DCs and macrophages. These results also point to specific signaling pathways that may be activated by the initial interaction of EBOV with DCs and which may influence the outcome of EBOV infection. Previous studies have demonstrated that VP40+GP VLPs, but not VP40 VLPs could stimulate DCs (Bosio et al., 2004; Ye et al., 2006). In our hands, VLPs containing the viral matrix protein, VP40 and the viral glycoprotein, GP, were found to induce a proinflammatory response. The importance of GP for the DC response is expected, and fits with its ability to induce a variety of cellular responses. The EBOV GP is the viral attachment and fusion protein (Bar et al., 2006; Feldmann et al., 2001), and it also exerts a variety of additional effects upon cells, including surface protein modulation (Simmons et al., 2002; Takada et al., 2000; Wahl-Jensen et al., 2005b), induction of anoikis (Alazard-Dany et al., 2006; Ray et al., 2004), and stimulation of cytokine production from human macrophages (Wahl-Jensen et al., 2005a) and dendritic cells (Bosio et al., 2004; Ye et al., 2006). Moreover, its vascular cytotoxicity is thought to be play an important role in virulence (Yang et al., 2000). In contrast, the presence of other viral proteins; of which NP was the most abundant, did not substantially alter DC responses. This observation is in spite of the fact that other viral components might be expected to modulate host cell responses to VLPs given their previously described functions. For example, the VP35 and VP24 proteins interfere with signaling pathways related to interferon responses (Basler et al., 2003; Basler et al., 2000; Bosio et al., 2003; Hartman, Towner, and Nichol, 2004; Reid, Cardenas, and Basler, 2005) (Reid et al., 2006). It remains unclear whether the VP35 and VP24 in “complete” VLPs reflects an inability to modulate DC responses when introduced into cells via VLPs or their relatively low abundance in the VLPs.

VLPs containing the viral matrix protein (VP40) and the viral glycoprotein (GP) were found to induce a proinflammatory response highly similar to a prototypical DC activator, LPS. This response included the production of several proinflammatory cytokines, as measured by a multiplex cytokine assay. Specifically, inflammatory cytokines IL-6, TNFα, and chemokines IL-8, MIP-1α, RANTES and IP-10 are all secreted by VP40+GP (Fig. 2) and cVLPs (not shown) stimulated DCs. This is consistent with previous studies that demonstrated the secretion of the above-mentioned cytokines (Bosio et al., 2004; Warfield et al., 2003; Ye et al., 2006) with the exception of IFN protein-10 (IP-10), a protein which acts to attract activated T cells and which plays a role in responses to viral infection (Dufour et al., 2002). Additionally activation of NF-κB and numerous other transcription factors (TFs) were demonstrated, with a multiplex TF array, following either VLP or LPS treatment of DCs. TFs activated by ten minutes were, for the most part, also stimulated after thirty minutes of VLP treatment (Table 2). Therefore, the results of the ten minute array corroborated the results of the thirty minute array. This also showed that VLP treatment induced rapid signaling. This raises the possibility that the activation may be occurring shortly after interaction of the VLP with receptors present at the plasma membrane of DCs. Further studies are needed to clarify whether internalization of the VLPs by the immature DCs is a requirement for DC stimulation. It is interesting to note that NF-κB was activated (>2 fold change) by VLPs, as compared to an unstimulated control, within 10 minutes of treatment (Table 2). However, in fig. 3, IκBα decreased significantly only after 30 minutes. The reason for this seeming discrepancy is unclear, but may reflect the fact two different parameters are being measured using two different assays. Nevertheless, NF-κB was shown to be activated by VLPs using two independent assays.

While the activation of NF-κB might have been predicted, given the role of NF-κB in proinflammatory cytokine production (Ali and Mann, 2004), it was important to demonstrate experimentally that this activation plays a critical role in VLP induced DC activation. This was addressed by employing previously described NF-κB inhibitors. Specifically, IL-6 cytokine production was abolished when NF-kB inhibitors SN50 and IKK2 inhibitors were used to pretreat DCs stimulated with VLPs. The SN50 peptide inhibitor blocks NF-kB nuclear translocation while IKK2 blocks IKKβ, a component of the IKK kinase complex. Taken together, these data indicate that VLPs induce IκBα degradation and that NF-κB activation is important for IL-6 secretion.

Interestingly, the transcription factor array data also suggested the activation of MAP kinase pathways. For example, VLP-activated TFs included TFs that regulate cell cycle control and apoptosis (EGR (Thiel and Cibelli, 2002), E2F-1 (Pardee, Li, and Reddy, 2004; Stevens and La Thangue, 2003)), stress and inflammatory responses (NF-kB (Ali and Mann, 2004), Ets (Sharrocks, 2001), STATs (Decker and Kovarik, 2000), USF-1 (Corre and Galibert, 2005), SIE (Wang, Lai, and Yang-Yen, 2003)) and mitogen and cytokine response (SIE , EGR (Decker et al., 2003), STATs (Decker, 1999)). Of these, Ets, SIE, STAT and USF TF family members can all be phosphorylated by the stress-induced MAPKs. Consistent with the potential MAPK activated TFs discovered through the array; we also demonstrated that VLPs can significantly activate ERK1/2 (Fig. 4). However, unlike LPS treatment, VLPs did not detectably activate p38 and SAPK/JNK (Fig. 4). Although both LPS and VLP treatment activated ERK1/2, they did so with different kinetics. As previously demonstrated in a study showing the kinetics of LPS-stimulated DC ERK1/2 activation (Ardeshna et al., 2000), ERK1/2 phosphorylation was maximal by 30 minutes while VLP treatment induced ERK1/2 activation that lasted up to 1 hour (Fig. 4-5). Cumulatively, the cytokine, TF and signaling pathway data suggest that VLPs activate DCs in a manner that is similar but not identical to the prototypical DC activator, LPS.

To further address the requirements for VP40+GP induced DC activation, the role of the GP mucin domain in DC activation was explored. As noted above, the heavily glycosylated mucin domain is required for several cellular responses to GP but is not required for GP-mediated cell attachment and entry, at least for GP pseudotyped viruses (Jeffers, Sanders, and Sanchez, 2002; Manicassamy et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2000). Although GPΔmucin was incorporated into VLPs at levels similar to GP, the VLPs containing GPΔmucin could not stimulate DC iκBα degradation and ERK phosphorylation to the same extent as VLPs containing wild type GP. The GPΔmucin VLPs also failed to induce IL-8 production (Fig. 5). The fact that the neutralizing antibody used in our ELISA (Fig. 5B) could bind the GPΔmucin in the VLPs and the fact that both wild type GP-VLPs and GPΔmucin-VLPs can associate with DCs to similar levels (Fig. 5E) suggests that GPΔmucin is in a native conformation and that VLPs with GPΔmucin can still infect cells. Since both wild type and mutant VLPs could presumably mediate virion entry, this would not explain the difference in signaling. Further studies are required to understand how the mucin domain contributes to signaling leading to DC stimulation.

Although DC responses to LPS and VLPs were not identical, many similarities were noted in our studies. It should be noted that it is difficult to exclude the possibility that a small amount of contaminating LPS could play a role in the stimulating capacity of our VLPs, however as previously demonstrated (Bosio et al., 2004), VLPs, unlike LPS, lose their stimulatory capacity when boiled (not shown). We also find that the minimal values obtained in the limulus amebocyte lysates assay employed to quantify endotoxin levels (< 0.03 IU/ μg total protein, not shown and (Fuller et al., 2006)) were similar for GPΔmucin VLPs as compared to GP VLPs (not shown). Therefore endotoxin contamination cannot explain the differences seen between the two types of VLPs.. Since LPS signals through TLR4, it is tempting to speculate that VLPs may also stimulate DCs through a TLR. However, GP interacts with a variety of cell surface molecules. The identity of the primary receptor(s) mediating EBOV entry is controversial (Simmons et al., 2003b) and one cannot exclude signaling from this receptor(s) as contributing to DC activation. In addition, GP can interact with a variety of other molecules, including C-type lectins, that are present upon DCs, monocytes and/or macrophages (Alvarez et al., 2002; Marzi et al., 2004; Mohamadzadeh et al., 2006; Simmons et al., 2003a; Takada et al., 2004). Given that the mucin domain is more glycosylated than other regions of GP, it is intriguing to speculate that interactions between C-type lectins and the mucin domain might contribute to signaling within the DCs.

In conclusion, we show that within one hour, EBOV GP-mediated signaling leads to the activation of both NF-κB and ERK1/2, and this response requires the presence of the GP mucin domain. Previous studies suggest that EBOV infection of DCs leads to poor pro-inflammatory cytokine production and DCs that are not fully matured and fail to effectively activate a T cell response (Bosio et al., 2003; Mahanty et al., 2003). We hypothesize that the signals activated by EBOV VLPs represent signals that are also transduced by live EBOV and contribute to the aberrant activation of DCs. Experiments are thus underway to define the mechanism(s) by which these pathways are activated by VLPs and to evaluate their significance in the context of EBOV infection.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from an NIH U19 grant (AI062623) to CFB. We would like to thank Kelley Boyd and Svetlana V. Burmakina for technical assistance with the multiplex cytokine assays and electron microscopy, respectively. We also want to thank Ana Fernandez-Sesma for helpful discussions and Lawrence W. Leung for his critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Disease Outbreak News: Marburg haemorrhagic fever. World Health Organization; http://www.who.int/csr/don/archive/disease/marburg_virus_disease/en/ [Google Scholar]

- Alazard-Dany N, Volchkova V, Reynard O, Carbonnelle C, Dolnik O, Ottmann M, Khromykh A, Volchkov VE. Ebola virus glycoprotein GP is not cytotoxic when expressed constitutively at a moderate level. J Gen Virol. 2006;87(Pt 5):1247–57. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81361-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali S, Mann DA. Signal transduction via the NF-kappaB pathway: a targeted treatment modality for infection, inflammation and repair. Cell Biochem Funct. 2004;22(2):67–79. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez CP, Lasala F, Carrillo J, Muniz O, Corbi AL, Delgado R. C-type lectins DC-SIGN and L-SIGN mediate cellular entry by Ebola virus in cis and in trans. J Virol. 2002;76(13):6841–4. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.13.6841-6844.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardeshna KM, Pizzey AR, Devereux S, Khwaja A. The PI3 kinase, p38 SAP kinase, and NF-kappaB signal transduction pathways are involved in the survival and maturation of lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Blood. 2000;96(3):1039–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baize S, Leroy EM, Georges-Courbot MC, Capron M, Lansoud-Soukate J, Debre P, Fisher-Hoch SP, McCormick JB, Georges AJ. Defective humoral responses and extensive intravascular apoptosis are associated with fatal outcome in Ebola virus-infected patients. Nat Med. 1999;5(4):423–6. doi: 10.1038/7422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baize S, Leroy EM, Georges AJ, Georges-Courbot MC, Capron M, Bedjabaga I, Lansoud-Soukate J, Mavoungou E. Inflammatory responses in Ebola virus-infected patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;128(1):163–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01800.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar S, Takada A, Kawaoka Y, Alizon M. Detection of cell-cell fusion mediated by Ebola virus glycoproteins. J Virol. 2006;80(6):2815–22. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.6.2815-2822.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basler CF, Mikulasova A, Martinez-Sobrido L, Paragas J, Muhlberger E, Bray M, Klenk HD, Palese P, Garcia-Sastre A. The Ebola virus VP35 protein inhibits activation of interferon regulatory factor 3. J Virol. 2003;77(14):7945–56. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.14.7945-7956.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basler CF, Wang X, Muhlberger E, Volchkov V, Paragas J, Klenk HD, Garcia-Sastre A, Palese P. The Ebola virus VP35 protein functions as a type I IFN antagonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(22):12289–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220398297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosio CM, Aman MJ, Grogan C, Hogan R, Ruthel G, Negley D, Mohamadzadeh M, Bavari S, Schmaljohn A. Ebola and Marburg viruses replicate in monocyte-derived dendritic cells without inducing the production of cytokines and full maturation. J Infect Dis. 2003;188(11):1630–8. doi: 10.1086/379199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosio CM, Moore BD, Warfield KL, Ruthel G, Mohamadzadeh M, Aman MJ, Bavari S. Ebola and Marburg virus-like particles activate human myeloid dendritic cells. Virology. 2004;326(2):280–7. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray M, Geisbert TW. Ebola virus: the role of macrophages and dendritic cells in the pathogenesis of Ebola hemorrhagic fever. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2005;37(8):1560–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corre S, Galibert MD. Upstream stimulating factors: highly versatile stress-responsive transcription factors. Pigment Cell Res. 2005;18(5):337–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2005.00262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker EL, Nehmann N, Kampen E, Eibel H, Zipfel PF, Skerka C. Early growth response proteins (EGR) and nuclear factors of activated T cells (NFAT) form heterodimers and regulate proinflammatory cytokine gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(3):911–21. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker T. Introduction: STATs as essential intracellular mediators of cytokine responses. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;55(12):1505–8. doi: 10.1007/s000180050390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker T, Kovarik P. Serine phosphorylation of STATs. Oncogene. 2000;19(21):2628–37. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour JH, Dziejman M, Liu MT, Leung JH, Lane TE, Luster AD. IFN-gamma-inducible protein 10 (IP-10; CXCL10)-deficient mice reveal a role for IP-10 in effector T cell generation and trafficking. J Immunol. 2002;168(7):3195–204. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmann H, Volchkov VE, Volchkova VA, Stroher U, Klenk HD. Biosynthesis and role of filoviral glycoproteins. J Gen Virol. 2001;82(Pt 12):2839–48. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-12-2839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller CL, Ruthel G, Warfield KL, Swenson DL, Bosio CM, Aman MJ, Bavari S. NKp30-dependent cytolysis of filovirus-infected human dendritic cells. Cellular Microbiology. 2006 doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00844.x. doi:10.1111/j.1462−5822.2006.00844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisbert TW, Hensley LE, Larsen T, Young HA, Reed DS, Geisbert JB, Scott DP, Kagan E, Jahrling PB, Davis KJ. Pathogenesis of Ebola hemorrhagic fever in cynomolgus macaques: evidence that dendritic cells are early and sustained targets of infection. The American journal of pathology. 2003;163(6):2347–70. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63591-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisbert TW, Jahrling PB. Differentiation of filoviruses by electron microscopy. Virus research. 1995;39(2−3):129–50. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(95)00080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman AL, Towner JS, Nichol ST. A C-terminal basic amino acid motif of Zaire ebolavirus VP35 is essential for type I interferon antagonism and displays high identity with the RNA-binding domain of another interferon antagonist, the NS1 protein of influenza A virus. Virology. 2004;328(2):177–84. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoenen T, Groseth A, Falzarano D, Feldmann H. Ebola virus: unravelling pathogenesis to combat a deadly disease. Trends in molecular medicine. 2006;12(5):206–15. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasenosky LD, Neumann G, Lukashevich I, Kawaoka Y. Ebola virus VP40-induced particle formation and association with the lipid bilayer. Journal of virology. 2001;75(11):5205–14. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.11.5205-5214.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffers SA, Sanders DA, Sanchez A. Covalent modifications of the ebola virus glycoprotein. J Virol. 2002;76(24):12463–72. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.24.12463-12472.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leroy EM, Baize S, Volchkov VE, Fisher-Hoch SP, Georges-Courbot MC, Lansoud-Soukate J, Capron M, Debre P, McCormick JB, Georges AJ. Human asymptomatic Ebola infection and strong inflammatory response. Lancet. 2000;355(9222):2210–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02405-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahanty S, Bray M. Pathogenesis of filoviral haemorrhagic fevers. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4(8):487–98. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01103-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahanty S, Hutchinson K, Agarwal S, McRae M, Rollin PE, Pulendran B. Cutting edge: impairment of dendritic cells and adaptive immunity by Ebola and Lassa viruses. J Immunol. 2003;170(6):2797–801. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.2797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manicassamy B, Wang J, Jiang H, Rong L. Comprehensive analysis of ebola virus GP1 in viral entry. J Virol. 2005;79(8):4793–805. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.8.4793-4805.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama T, Rodriguez LL, Jahrling PB, Sanchez A, Khan AS, Nichol ST, Peters CJ, Parren PW, Burton DR. Ebola virus can be effectively neutralized by antibody produced in natural human infection. Journal of virology. 1999;73(7):6024–30. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.6024-6030.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzi A, Gramberg T, Simmons G, Moller P, Rennekamp AJ, Krumbiegel M, Geier M, Eisemann J, Turza N, Saunier B, Steinkasserer A, Becker S, Bates P, Hofmann H, Pohlmann S. DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR interact with the glycoprotein of Marburg virus and the S protein of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Virol. 2004;78(21):12090–5. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.21.12090-12095.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamadzadeh M, Coberley SS, Olinger GG, Kalina WV, Ruthel G, Fuller CL, Swenson DL, Pratt WD, Kuhns DB, Schmaljohn AL. Activation of triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 on human neutrophils by marburg and ebola viruses. J Virol. 2006;80(14):7235–44. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00543-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda T, Sagara H, Suzuki E, Takada A, Kida H, Kawaoka Y. Ebola virus VP40 drives the formation of virus-like filamentous particles along with GP. Journal of virology. 2002;76(10):4855–65. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.10.4855-4865.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardee AB, Li CJ, Reddy GP. Regulation in S phase by E2F. Cell Cycle. 2004;3(9):1091–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray RB, Basu A, Steele R, Beyene A, McHowat J, Meyer K, Ghosh AK, Ray R. Ebola virus glycoprotein-mediated anoikis of primary human cardiac microvascular endothelial cells. Virology. 2004;321(2):181–8. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2003.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid SP, Cardenas WB, Basler CF. Homo-oligomerization facilitates the interferon-antagonist activity of the ebolavirus VP35 protein. Virology. 2005;341(2):179–89. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid SP, Leung LW, Hartman AL, Martinez O, Shaw ML, Carbonnelle C, Volchkov VE, Nichol ST, Basler CF. Ebola virus VP24 binds karyopherin alpha1 and blocks STAT1 nuclear accumulation. J Virol. 2006;80(11):5156–67. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02349-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis e Sousa C. Toll-like receptors and dendritic cells: for whom the bug tolls. Seminars in immunology. 2004;16(1):27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez A, Lukwiya M, Bausch D, Mahanty S, Sanchez AJ, Wagoner KD, Rollin PE. Analysis of human peripheral blood samples from fatal and nonfatal cases of Ebola (Sudan) hemorrhagic fever: cellular responses, virus load, and nitric oxide levels. J Virol. 2004;78(19):10370–7. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10370-10377.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharrocks AD. The ETS-domain transcription factor family. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2(11):827–37. doi: 10.1038/35099076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons G, Reeves JD, Grogan CC, Vandenberghe LH, Baribaud F, Whitbeck JC, Burke E, Buchmeier MJ, Soilleux EJ, Riley JL, Doms RW, Bates P, Pohlmann S. DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR bind ebola glycoproteins and enhance infection of macrophages and endothelial cells. Virology. 2003a;305(1):115–23. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons G, Rennekamp AJ, Chai N, Vandenberghe LH, Riley JL, Bates P. Folate receptor alpha and caveolae are not required for Ebola virus glycoprotein-mediated viral infection. J Virol. 2003b;77(24):13433–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.24.13433-13438.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons G, Wool-Lewis RJ, Baribaud F, Netter RC, Bates P. Ebola virus glycoproteins induce global surface protein down-modulation and loss of cell adherence. J Virol. 2002;76(5):2518–28. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.5.2518-2528.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens C, La Thangue NB. A new role for E2F-1 in checkpoint control. Cell Cycle. 2003;2(5):435–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan NJ, Peterson M, Yang ZY, Kong WP, Duckers H, Nabel E, Nabel GJ. Ebola virus glycoprotein toxicity is mediated by a dynamin-dependent protein-trafficking pathway. J Virol. 2005;79(1):547–53. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.1.547-553.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada A, Fujioka K, Tsuiji M, Morikawa A, Higashi N, Ebihara H, Kobasa D, Feldmann H, Irimura T, Kawaoka Y. Human macrophage C-type lectin specific for galactose and N-acetylgalactosamine promotes filovirus entry. Journal of virology. 2004;78(6):2943–7. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.6.2943-2947.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada A, Watanabe S, Ito H, Okazaki K, Kida H, Kawaoka Y. Downregulation of beta1 integrins by Ebola virus glycoprotein: implication for virus entry. Virology. 2000;278(1):20–6. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel G, Cibelli G. Regulation of life and death by the zinc finger transcription factor Egr-1. J Cell Physiol. 2002;193(3):287–92. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmins J, Scianimanico S, Schoehn G, Weissenhorn W. Vesicular release of ebola virus matrix protein VP40. Virology. 2001;283(1):1–6. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.0860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl-Jensen V, Kurz SK, Hazelton PR, Schnittler HJ, Strèoher U, Burton DR, Feldmann H. Role of Ebola virus secreted glycoproteins and virus-like particles in activation of human macrophages. Journal of virology. 2005a;79(4):2413–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.4.2413-2419.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl-Jensen VM, Afanasieva TA, Seebach J, Strèoher U, Feldmann H, Schnittler HJ. Effects of Ebola virus glycoproteins on endothelial cell activation and barrier function. Journal of virology. 2005b;79(16):10442–50. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10442-10450.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JM, Lai MZ, Yang-Yen HF. Interleukin-3 stimulation of mcl-1 gene transcription involves activation of the PU.1 transcription factor through a p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(6):1896–909. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.6.1896-1909.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warfield KL, Bosio CM, Welcher BC, Deal EM, Mohamadzadeh M, Schmaljohn A, Aman MJ, Bavari S. Ebola virus-like particles protect from lethal Ebola virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(26):15889–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2237038100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang ZY, Duckers HJ, Sullivan NJ, Sanchez A, Nabel EG, Nabel GJ. Identification of the Ebola virus glycoprotein as the main viral determinant of vascular cell cytotoxicity and injury. Nat Med. 2000;6(8):886–9. doi: 10.1038/78645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye L, Lin J, Sun Y, Bennouna S, Lo M, Wu Q, Bu Z, Pulendran B, Compans RW, Yang C. Ebola virus-like particles produced in insect cells exhibit dendritic cell stimulating activity and induce neutralizing antibodies. Virology. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]