Abstract

Background

Both physiologic and pathophysiologic conditions affect the myocardium's substrate use and consequently, its structure, function, and adaptability. The effect of sex on myocardial oxygen, glucose, and fatty acid metabolism in humans is unknown.

Methods and Results

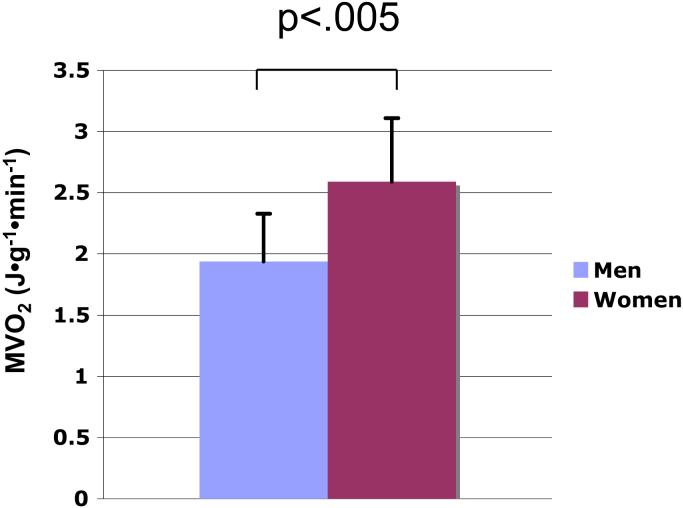

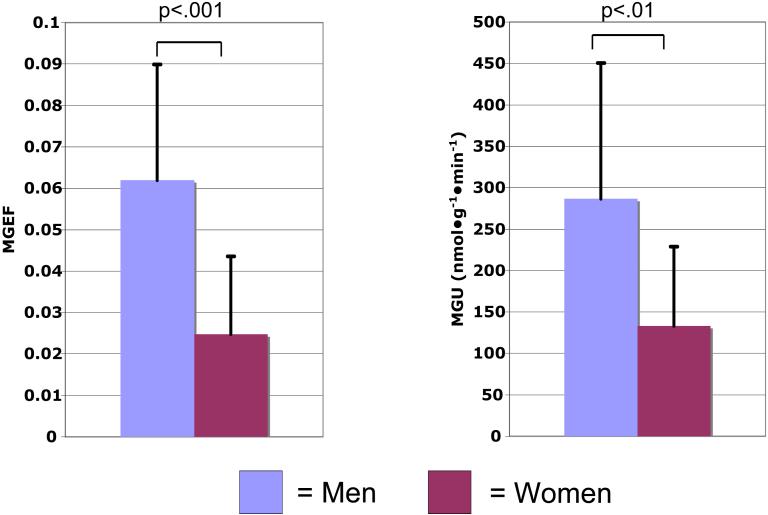

We studied 25 young subjects (13 women) using positron emission tomography quantifying myocardial blood flow, oxygen consumption (MVO2), glucose and fatty acid extraction and metabolism. MVO2, was higher in women compared with men (5.74±1.08 vs. 4.26±0.69μmol•g−1•min−1, p<.005). Myocardial glucose extraction fraction, and utilization were lower in women compared with men (0.025±.019 vs. 0.062±0.028, p<.001 and 133±96 vs. 287±164 nmol•g−1•min−1, p<.01). There were no sex differences in myocardial blood flow, fatty acid metabolism, plasma glucose, fatty acid, or insulin levels. Female sex was an independent predictor of increased MVO2 (p=.01), decreased myocardial glucose extraction fraction and utilization (p<.005, and < .05, respectively). Insulin sensitivity was an independent predictor of increased myocardial glucose extraction fraction and utilization (p<.01, and p=.01).

Conclusions

Further studies are necessary to elucidate the mechanisms responsible for sex-associated differences in myocardial metabolism. However, the presence of such differences may provide a partial explanation for the observed sex-related differences in the prevalence and manifestation of a variety of cardiac disorders.

Keywords: sex, myocardial metabolism, glucose, myocardial oxygen consumption

Myocardial metabolism and cardiac function are inextricably linked: the myocardium metabolizes substrates in order to generate ATP, the hydrolysis of which allows for cardiac function. In the postnatal myocardium, metabolism of fatty acids provide most of the energy required; glucose, and to a lesser degree lactate, ketones, intracellular triglyceride, and glycogen also provide energy. However, the myocardium may switch its preference away from free fatty acids and towards glucose depending on physiological or pathophysiological conditions and substrate availability.1-5 The myocardium's choice of substrate affects its oxygen consumption, efficiency, and metabolic regulatory signals generated.6 Thus, the heart's ability to switch from using one substrate to another, impacts its ability to cope with different conditions. For example, in ischemia, ß-oxidation of fatty acids is halted and glucose, the more oxygen-efficient substrate, is preferred.7 Consequently, conditions that detrimentally affect the myocardium's ability to use glucose may adversely alter the myocardium's ability to adapt to ischemia. E.g., humans with type I diabetes have an increased reliance on fatty acid metabolism, which may detrimentally affect the diabetic myocardium's ability to adapt to ischemia and survive.4

There are also data that show that sex affects myocardial metabolism in animal models, and skeletal muscle and liver substrate in humans under a variety of conditions.8-13 Whether sex affects myocardial metabolism in young, fasting humans is not clear; however, it is clear that there are sex-related differences in morbidity and mortality from various cardiovascular diseases and given the known link between metabolism and function, it is reasonable to theorize that there may be sex-related differences in myocardial metabolism playing a role.14 Although sex hormone levels and other differences between men and women are potential effectors or confounders of sex-related differences, the purpose of this study was to test the ground breaking hypothesis that sex, itself, is related to and affects myocardial substrate metabolism in vivo, in humans and in so doing lay the foundation for further investigation of sex-related differences in metabolism.

METHODS

Study subjects

Young, healthy, nonobese, sedentary subjects, 13 premenopausal women and 12 men, 20−44 years old, participated in this prospective study. All subjects completed a comprehensive medical evaluation, including a history, physical examination, electrocardiogram, routine blood tests, an oral glucose tolerance test, lipid profile, and a rest/stress echocardiogram. Those who had impaired fasting glucose, glucose tolerance, or diabetes during an oral glucose tolerance test, hypertension, a history of coronary artery or other cardiac disease, a history of smoking cigarettes within the last 12 months, or who had an abnormal rest/stress echo were excluded; those who performed routine aerobic exercise equal to or more than 30 minutes/day for more than 2 days a week were excluded from the study in order to minimize any potential confounding effect of aerobic training on myocardial metabolism since training has known effects on hemodynamics and cardiac structure. Subjects also underwent dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry using a Hologic Discovery QDR #70570 and software version 12.4 (Hologic Inc., Bedford, MA) for body composition measurement. Five women were taking contraception measure(s) (4 were taking oral and 1 was receiving intramuscular contraceptive agents). Serum progesterone and estradiol and estrone levels were measured and last menstrual dates were recorded in all the women for the determination of cycle phase. No data on any subject have been previously published. All participants signed the written informed consent form, which was approved by the Institutional Reveiw BOard, the General Clinical Research Center, and the Radioactive Drug Research Committee at the Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO.

Experimental procedure

Subjects were fasted overnight (12 hours) and studied the following a.m. (in order to avoid possible confounding effects of interindividual differences in postpradial absorption rates). The morning of the study an 18- or 20-gauge catheter was inserted into an antecubital vein for radiopharmaceutical infusion. All subjects underwent positron emission tomography (PET) imaging at 8:00 a.m. to avoid circadian variations in hormones, myocardial metabolism, and function.15 All studies were performed on a conventional commercially available tomograph (Siemens ECAT 962 HR+, Siemens Medical Systems, Iselin, NJ). Blood pressure and heart rate were obtained throughout the study. PET was used to measure myocardial blood flow with 15O-water, MVO2 with 1-11C-acetate, myocardial glucose extraction fraction and utilization with 1-11C-glucose, and fatty acid extraction fraction, utilization, and oxidation with 1-11C–palmitate. During the study, venous blood samples were obtained at predetermined intervals to measure plasma substrate (glucose, fatty acids, and lactate) and insulin levels as well as radiolabeled metabolites, which are required for compartmental modeling of the kinetics of the metabolic tracers.16-18 Plasma substrate levels were determined from venous rather than arterial samples; however, because our subjects were in the resting state, differences in substrate concentrations between the 2 sample sites would be expected to be negligible. Radiolabeled metabolites were also determined using venous rather than arterial samples; we have used venous 11CO2 based on the results of previous studies and have showed that under resting conditions the differences in arterial and mixed venous 11CO2 levels was minimal and in post-hoc analyses did not contribute to a significant difference in MVO2, myocardial fatty acid or glucose utilization.16-18

Image analyses

PET image analysis for the quantification of myocardial blood flow (in mL•g−1•min−1), MVO2 (in μmol•g−1•min−1), glucose and fatty acid metabolism was performed using well-validated techniques.16-19 In brief, myocardial glucose or fatty acid extraction fraction is the fraction of glucose or fatty acid extracted by the myocardium. Myocardial glucose utilization and fatty acid utilization (in nmol•g−1•min−1) represent the total amount of glucose or fatty acid utilized per minute by the myocardium. Myocardial fatty acid oxidation (in nmol•g−1•min−1) represents the total amount of fatty acid oxidized by the myocardium. For the purposes of calculating myocardial efficiency, MVO2 was converted to its volume equivalent using the conversion factor 0.0224 ml/μmol O2 , then to its energy equivalent using the conversion factor 2.059 kg•m/ml oxygen consumed, and finally to SI units (J•g−1•min−1) by multiplying by g, the gravitational constant (9.81 m/sec2).

Echocardiography

During the PET study, all subjects had a complete 2-D and Doppler echocardiographic examination using a Sequoia-C256® (Acuson-Siemens, Mountain View, CA) immediately after the imaging for MVO2. Left ventricular (LV) end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes were determined using the method of discs. LV mass was determined using the area-length method, and LV mass index = LV mass/body surface area according to the recommendations of Americanp.8) Society of Echocardiography.20 Relative wall thickness was calculated as (2 × posterior wall thickness at end-diastole)/LV diastolic dimension. LV ejection fraction was calculated online using the modified Simpson's method. Cardiac output (mL•min−1) = the time-velocity integral of the LV outflow × LV outflow tract area. LV minute work per gram of myocardium (LVMWg) = mean arterial pressure × cardiac output × 0.0000136 × g / LV mass. The number 0.0000136 represents a conversion factor from units of pressure and volume (mm Hg•mL) to work (kg•m) (2) and g represents the gravitational constant for the purposes of converting to SI units (J•g−1•min−1). LV efficiency was calculated as the ratio (LVMWg / MVO2) ×100%. Subjects also underwent tissue Doppler imaging in order to quantify the longitudinal, early, peak diastolic myocardial relaxation velocity (Em) and the longitudinal, peak systolic shortening velocity (Sm) for the assessment of preload-independent systolic and diastolic function, respectively.21 Em and Sm values measured from the septal and lateral walls were averaged to obtain one Em and Sm value per subject.

Plasma analyses

Plasma glucose concentration was determined by using the Cobas Mira analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Insulin was measured by radioimmunoassay (Linco Research Co., St. Charles, MO). Free fatty acid concentrations were measured by using an enzymatic colorimetric method (NEFA C kit, WAKO Chemicals USA, Inc., Richmond, VA). Lactate was measured using a photospectrometry kit (Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, MO). Estrogen levels were measured using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (Mayo, Rochester, MN); progesterone levels were measured by chemiluminescence enzyme immunoassay (Advia redipack, Bayer Corporation).

Insulin resistance

Insulin sensitivity was quantified by the homeostasis model assessment, or “HOMA,” as described previously.22 Specifically, HOMA is calculated as ([fasting insulin (in μU/mL)] × [fasting glucose (mM)])/22.5.

Statistical analysis

Statistical calculations were performed using SAS version 8.2. Data are shown as the mean ± standard deviation. Differences between the continuous variables were determined using student t-tests as the data were normally distributed. Chi-square tests were used to determine the differences in categorical variables between the 2 groups. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to determine the relationship between continuous variables. In order to be tested in the multivariate model, we required that an independent variable be significantly related to the outcome variable at a significance level of p ≤ .10. A type III sum of squares was used to calculate the independent predictors of the predetermined outcome variables that had a significant relationship with sex, (i.e., MVO2, myocardial glucose extraction fraction, glucose uptake, and utilization). A p value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics and echocardiographic measurements

Baseline characteristics of the subjects are shown in Table 1. There were no statistical differences between the men and women with respect to age, body mass index, or cholesterol levels. Cardiac structure, function, and hemodynamic data at the time of PET imaging are shown in Table 2. Systolic, but not diastolic, blood pressure was higher in the men. LV mass was higher in the men than the women, and LV mass index trended toward being higher in the men; relative wall thickness, though, was not different between the groups. There were no statistical differences in systolic function as measured by Sm, ejection fraction, or cardiac work, between the men and women. Diastolic function, as measured using the tissue Doppler-derived Em, was borderline higher in the men.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Men | Women | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 12 | 13 | |

| Age (yrs) | 28 ± 7 | 26 ± 4 | .37 |

| Race (% Caucasian) | 83 | 46 | .10 |

| Height (cm) | 182 ± 6 | 163 ± 4 | <.0001 |

| Weight (kg) | 79 ± 7 | 64 ± 5 | <.0001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.7 ± 2.6 | 24.4 ± 2.8 | .54 |

| Body surface area (m2) | 1.97 ± 0.12 | 1.66 ± 0.09 | <.0001 |

| Fat free mass (kg) | 66 ± 5 | 44 ± 2 | <.0001 |

| % Body fat | 16 ± 6 | 33 ± 6 | <.0001 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 164 ± 21 | 157 ± 31 | .53 |

| Low-density lipoprotein (mg/dL) | 96 ± 18 | 85 ± 27 | .25 |

| High-density lipoprotein (mg/dL) | 51 ± 12 | 59 ± 12 | .08 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 89 ± 29 | 65 ± 27 | <.05 |

| HOMA (μU/mL) | 0.84 ± .45 | 1.24 ± .62 | .08 |

HOMA = homeostasis model assessment for insulin resistance.

Table 2.

Hemodynamics, Cardiac Structure and Function During PET Imaging

| Men | Women | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemodynamics | |||

| SBP (mm Hg) | 119 ± 8 | 106 ± 13 | <.01 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 66 ± 6 | 66 ± 9 | .99 |

| MAP (mm Hg) | 83 ± 6 | 79 ± 9 | .20 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 55 ± 10 | 63 ± 11 | .06 |

| Rate-pressure product (mm Hg*bpm) | 6523 ± 1281 | 6650 ± 1277 | .81 |

| Cardiac structure | |||

| LV mass (g) | 172 ± 33 | 127 ± 15 | <.0005 |

| LV mass index (g/m2) | 87 ± 16 | 77 ± 9 | .05 |

| Relative wall thickness | 0.41 ± 0.09 | 0.37 ± 0.05 | .13 |

| Ejection fraction | 60 ± 4 | 61 ± 6 | .56 |

| Cardiac systolic function and efficiency | |||

| Sm (cm/s) | 8.4 ± 1.0 | 8.4 ± 1.2 | .90 |

| Cardiac output (L/min) | 4.4 ± 0.8 | 3.8 ± 0.8 | .10 |

| Cardiac minute work (J•g-1•min-1) | 0.29 ± .09 | 0.32 ± .08 | .36 |

| Efficiency (%) | 14.6 ± 3.4 | 12.4 ± 2.3 | .07 |

| Cardiac diastolic function | |||

| Em (cm/s) | 17.3 ± 2.4 | 15.4 ± 2.4 | .05 |

SBP = systolic blood pressure, DBP = diastolic blood pressure, MAP = mean arterial pressure, LV = left ventricular, Em = mitral annular velocity during diastole, Sm = mitral annular velocity during systole

Plasma substrate and hormone levels

Between men and women, there were no statistical differences in plasma glucose (4.94 ± 0.33 vs. 4.85 ± 0.36 μmol/mL, p=.51), fatty acid, or lactate levels (739 ± 273 vs. 637 ± 162 nmol/mL, p=.27) at the time of the PET study (Table 3). The men had higher triglyceride levels (Table 1, p<.05). The difference between plasma insulin levels or insulin sensitivity between the men and women was not significant although there was a trend towards the men having a lower fasting insulin level (3.9±2.1 vs. 5.7±2.8μmol/mL, p=.07) and consequently trending towards being more insulin sensitive per HOMA (Table 1). Of the women, 5 were in the luteal, 6 were in the follicular, and 1 was in the menstrual phase, and the menstrual phase status of 1 was not known. The levels of estradiol and progesterone for the women in the follicular phase were ≤ 56 pg/mL and ≤ 2.3 ng/mL, respectively, and the mean levels of estrogen and progesterone for the women in the luteal phase were 118 ± 23 pg/mL and 11.8 ± 7.4 ng/mL. There was no relationship between these hormone levels and MVO2, or myocardial glucose extraction fraction or utilization.

Table 3.

MBF and Fatty Acid Metabolism

| Men | Women | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MBF (mL•g-1•min-1) | 0.99 ± 0.19 | 1.13 ± .27 | .16 |

| Plasma free fatty acid level (nmol/mL) | 590 ± 213 | 692 ± 251 | .29 |

| Myocardial fatty acid extraction fraction | 0.393 ± 0.072 | 0.349 ± 0.089 | .18 |

| Myocardial fatty acid utilization (nmol•g-1•min-1) | 222 ± 93 | 249 ± 77 | .44 |

| Myocardial fatty acid oxidation (nmol•g-1•min-1) | 197 ± 71 | 200 ± 67 | .93 |

Myocardial blood flow, MVO2, and efficiency

Values for myocardial blood flow and MVO2 are shown in Table 3 and Figure 1. Myocardial blood flow did not differ between the 2 groups, but MVO2 was significantly higher in the women than the men (p <.005). Post-hoc analysis excluding the women who were taking any type of hormonal contraception still showed that women had a significantly higher MVO2 (p<.05). In the univariate analyses comparing the predetermined continuous variables with MVO2, only age (r = −.48, p<.05), and HOMA (r = .43,p <.05) were found to be significantly correlated with MVO2. In the multivariate analysis only age and female sex were independent predictors of increased MVO2 (p<.05, p=.01, respectively). In this model, age and sex predicted 54% of the variability of MVO2. Efficiency trended higher in men (p=.07) but was not significantly related to sex or the other predetermined variables in a univariate analysis or multivariate model.

Figure 1.

Sex-related myocardial oxygen consumption (MVO2) differences

Myocardial glucose metabolism

As shown in Figure 2, myocardial glucose extraction fraction was significantly higher in the men than the women (0.062 ± 0.028 vs. 0.025 ± 0.019). Myocardial glucose utilization was also significantly higher in the men when compared with women (287 ± 164 vs. 133 ± 96 nmol•g−1•min−1). Post-hoc analysis excluding the subjects who were taking any type of hormonal contraception still showed that women had a significantly lower myocardial glucose extraction fraction compared with the men (p<.05). Among the predetermined, continuous, independent variables (body mass index, age, relative wall thickness, mean arterial pressure, and HOMA) that were tested for their level of association with the myocardial glucose extraction fraction and metabolism measures, only HOMA was significantly related to myocardial glucose extraction fraction (r = −.60, p<.005) and utilization (r = −.58, p<.005). In the multivariate analysis sex and HOMA were both independent predictors of myocardial glucose extraction fraction (p<.005, p<.01, respectively), and the model predicted 56% of the variability in myocardial glucose extraction fraction. Similarly, sex and HOMA were independent predictors of myocardial glucose utilization (p<.05, p=.01, respectively). The multivariate models incorporating sex and HOMA predicted 50 and 45% of the variation in myocardial glucose utilization.

Figure 2.

Left graph, MGEF = myocardial glucose extraction fraction; right, MGU = myocardial glucose utilization.

Myocardial glucose extraction fraction and utilization: sex differences

Myocardial fatty acid metabolism

Measurements of myocardial fatty acid extraction fraction, utilization, and oxidation are shown in Table 3. In contrast to measurements of myocardial glucose metabolism, measures of myocardial fatty acid uptake and metabolism were similar between the groups.

DISCUSSION

The results of the current study are the first to demonstrate that sex differences in myocardial glucose utilization and MVO2 exist, with the hearts of young, healthy, nonobese women using less glucose and more oxygen than the hearts of age-matched men at rest. This cannot be explained by differences in myocardial blood flow, insulin sensitivity, hemodynamics, myocardial work, or the plasma substrate environment.

These findings expand upon our knowledge of sex-related differences in metabolism derived from studies of animal myocardium and from studies of other organs, in vivo, in humans. For example, results of studies in a transgenic mouse model demonstrated greater myocardial glycogen preservation, and studies in diabetic rat models demonstrated sex differences in myocardial metabolism, with female rats exhibiting less myocardial glucose and more fatty acid metabolism than males (although there were no sex-differences in metabolism in the nondiabetic controls).12,13 Studies of whole body and liver metabolism in humans also demonstrated the existence of sex-related differences in basal whole body lipolytic rates, fatty acid uptake, and very low density lipoprotein secretion rates and in skeletal muscle carbohydrate metabolism during and after exercise or after fasting.8-11,23-25

Differences in hormonal stimulation may play a role in the mechanism of sex-related differences in myocardial metabolism since animal studies have shown that estrogen decreases glucose oxidation, gluconeogenesis, and glycogenolysis, and increases fatty acid oxidation in liver and skeletal muscle.26-29 Myocardial glucose utilization may be decreased by estrogen because it is known to upregulate nitric oxide synthases, which cause a reduction in AMPK-stimulated GLUT-4 translocation to the cell surface, thereby inhibiting myocardial glucose uptake.30-32 However, the lack of a direct relationship between hormone levels and metabolic measures in our study and results from other studies of hormone effects suggest that the relationship between sex hormones and their effects is more complicated than a simple direct relationship between estradiol level and its putative effects. For example, studies of vascular function in both animal models and humans demonstrate sexually dimorphic responses to the same levels of estradiol.33,34 Thus, the exact molecular basis of the sex-related differences in myocardial glucose metabolic profiles that we have demonstrated in this study, is not yet clearly defined but is likely to be a complicated interaction involving genomic differences, sex hormones, hormone receptors, and metabolites.

Our finding of increased MVO2 in the young women, despite no statistical difference in cardiac work (and hence a trend toward less efficiency), may be due to an effect of estrogen since there is data from animal studies that shows that uncoupling proteins may be upregulated by estrogen, which could lead to increased oxygen consumption.35 It should be noted, however, that in our study, the relationship defined as efficiency, only reflects external cardiac work performed per MVO2; also, the slightly higher mean cardiac work in the women may account for some, though likely not all, of the increase in MVO2. Some of the difference in MVO2 between the sexes may result from differences in glucose oxidation (we have only measured myocardial glucose utilization in the current study – not oxidation), differences in metabolism of endogenous substrates (e.g., glycogen and triglyceride) that our current PET technique can not measure, and/or differences in metabolism of other exogenous substrates (e.g., ketones, amino acids). Further studies are needed to evaluate the possibility that sex-related differences in uncoupling proteins and/or their regulation impact MVO2 in humans and how oxidation of substrates other than exogenous fatty acids impace sex-related differences in myocardial metabolism.

The results of our study are seemingly in contrast to those from another PET study that suggested that there were no sex differences in myocardial metabolism between men and women during a hyperinsulinemic/euglycemic clamp; however, this study did not examine the fasted, resting state.36 The differences between the results of our study and the previous study may be due to the myocardial glucose uptake-enhancing effect of exogenous insulin infusion overwhelming sex-related differences in myocardial glucose uptake.

Myocardial fatty acid uptake, utilization, and oxidation were not statistically different between the women and men in this study; this may be due to differences in oxidation of other substrates exogenous to (e.g., lactate and pyruvate) or endogenous to (e.g., intramyocellular triglyceride) the heart that may also be significantly involved in the overall contribution to MVO2, so that a precisely inverse relationship between glucose and fatty acid utilization is not apparent.37

Study limitations

1) This study was performed in a select group of young, healthy subjects and thus our findings may not apply to all men and women. For example, relatively small number of nonwhite men limits this study's ability to make strong conclusions as to a possible interaction between sex and race and the dependent variables. 2) This study was not designed to analyze the effect of sex on myocardial metabolism in subjects with ischemia or other cardiac conditions (such as the postprandial state); thus our theory that the sex-related differences in myocardial metabolism that we report here have implications on metabolism and outcomes in ischemia needs to be tested in future studies. 3) Also, although the women were in different phases of their menstrual cycle, some metabolism studies of some organs such as liver have not shown an effect of menstrual cycle.38 4) We are not able to measure endogenous myocardial glycogen or triglyceride metabolism, so that we cannot detect the degree to which metabolism of these substrates may contribute to the differences in myocardial metabolism shown in this study. 5) Of note, although the cardiac work measurements in the study subjects are relatively low, the subjects were healthy and at rest and hence had low mean arterial pressure and cardiac output. The stroke volume indexed to body surface area in bothe the men and women (42 ± 9 mL/m2 and 37 ± 5 mL/m2, respectively) were within normal limits.39

Clinical implications

Although speculative, it is tempting to contemplate the implications of these gender differences in MVO2 and glucose metabolism. Sex differences in myocardial glucose and oxygen metabolism in young, healthy, nonobese humans may play a role in sex-related outcome differences in cardiovascular disease given the intrinsic interaction between myocardial substrate preference, metabolism, cardiac function, and adaptability to various conditions.6 For example, our observed sex differences in myocardial metabolism may detrimentally affect outcome in young women affected by myocardial ischemia – a condition associated with a decline in ß-oxidation of fatty acids, and an increased reliance on glucose metabolism. This could potentially explain, at least in part, why young women (although much less likely to suffer a myocardial infarction) have a much higher mortality from myocardial infarction than men – a difference that is not fully accounted for by differences in medical history, clinical severity of infarction, or early management.14 To be certain, differences other than myocardial substrate metabolism likely play a role in this discrepancy in cardiovascular outcomes; however, the significant associations between sex and oxygen and glucose metabolism shown in the current study provide a new paradigm for future investigations of sex-related cardiovascular outcome differences and may help refine future research in metabolic manipulation of the myocardium as it pertains to men and women. The degree to which non-hormone related genetic differences, sex hormones, and adipokines may affect myocardial substrate utilization in men and women with cardiac pathophysiologic conditions deserves further investigation.

Conclusions

Sex is an independent predictor of MVO2 and myocardial glucose metabolism in young, healthy, nonobese humans at rest, with women having a higher MVO2, and lower myocardial glucose extraction fraction and utilization than men. The current study increases the complexity of our understanding of myocardial metabolism and its regulation, which are altered by substrate availability, cardiac work, pathophysiologic conditions, and physiologic conditions, such as aging, and now sex. Future studies are needed to determine if sex-related differences in myocardial metabolism contribute to known sex-related outcome differences in cardiovascular diseases.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sam Klein, MD and Kristin O'Callaghan for their editorial assistance; Theresa Butler, RN and Shalonda Scott for their technical assistance; and Ava Ysaguirre for assistance with the manuscript preparation. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health RO1-HL073120, RO1-AG015466, and M01-RR000036.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HD145902 (Building Interdisciplinary Research in Women's Health), RR00036 (General Clinical Research Center), DK56341 (Clinical Nutrition Research Unit), K23-HL077179, RO1-AG15466, PO1- HL13581, and HL73120 Bethesda MD, USA and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation grant No. 051893, AHA02255732, Princeton, NJ, USA.

List of abbreviations

- MVO2

myocardial oxygen consumption

- PET

positron emission tomography

- LV

left ventricular

- HOMA

homeostasis model assessment

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Opie LH. Cardiac Metabolism. the Effect of Some Physiologic, Pharmacologic, and Pathologic Influences. Am Heart J. 1965;69:401–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(65)90278-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kates AM, Herrero P, Dence C, Soto P, Srinivasan M, Delano DG, et al. Impact of aging on substrate metabolism by the human heart. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:293–9. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02714-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peterson LR, Herrero P, Schechtman KB, Racette SB, Waggoner AD, Kisrieva-Ware Z, et al. Effect of obesity and insulin resistance on myocardial substrate metabolism and efficiency in young women. Circulation. 2004;109:2191–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000127959.28627.F8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herrero P, Peterson LR, McGill JB, Matthew S, Lesniak D, Dence C, et al. Increased myocardial fatty acid metabolism in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:598–604. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlson LA, Kaijser L, Rossner S, Wahlqvist ML. Myocardial metabolism of exogenous plasma triglycerides in resting man. Studies during alimentary lipaemia and intravenous infusion of a fat emulsion. Acta Med Scand. 1973;193:233–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taegtmeyer H, Wilson CR, Razeghi P, Sharma S. Metabolic energetics and genetics in the heart. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1047:208–18. doi: 10.1196/annals.1341.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Razeghi R, Young ME, Abbasi S, Taegtmeyer H. Hypoxia in vivo decreases peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha-regulated gene expression in rat heart. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;287:5–10. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mittendorfer B, Patterson BW, Klein S, Sidossis LS. VLDL-triglyceride kinetics during hyperglycemia-hyperinsulinemia: effects of sex and obesity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;284:E708–15. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00411.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mittendorfer B, Patterson BW, Klein S. Effect of sex and obesity on basal VLDL-triacylglycerol kinetics. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:573–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.3.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruby BC, Coggan AR, Zderic TW. Gender differences in glucose kinetics and substrate oxidation during exercise near the lactate threshold. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92:1125–32. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00296.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tarnopolsky LJ, MacDougall JD, Atkinson SA, Tarnopolsky MA, Sutton JR. Gender differences in substrate for endurance exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1990;68:302–8. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.68.1.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Djouadi F, Weinheimer CJ, Saffitz JE, Pitchford C, Bastin J, Gonzalez FJ, et al. A gender-related defect in lipid metabolism and glucose homeostasis in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1083–91. doi: 10.1172/JCI3949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Desrois M, Sidell RJ, Gauguier D, Davey CL, Radda GK, Clarke K. Gender differences in hypertrophy, insulin resistance and ischemic injury in the aging type 2 diabetic rat heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;37:547–55. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaccarino V, Parsons L, Every NR, Barron HV, Krumholz HM. Sex-based differences in early mortality after myocardial infarction. National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2 Participants. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:217–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907223410401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young ME, Razeghi P, Cedars AM, Guthrie PH, Taegtmeyer H. Intrinsic diurnal variations in cardiac metabolism and contractile function. Circ Res. 2001;89:1199–208. doi: 10.1161/hh2401.100741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herrero P, Weinheimer CJ, Dence C, Oellerich WF, Gropler RJ. Quantification of myocardial glucose utilization by PET and 1-carbon-11-glucose. J Nucl Cardiol. 2002;9:5–14. doi: 10.1067/mnc.2001.120635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bergmann SR, Weinheimer CJ, Markham J, Herrero P. Quantitation of myocardial fatty acid metabolism using PET. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:1723–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buck A, Wolpers HG, Hutchins GD, Savas V, Mangner TJ, Nguyen N, Schwaiger M. Effect of carbon-11-acetate recirculation on estimates of myocardial oxygen consumption by PET. J Nucl Med. 1991;32:1950–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bergmann SR, Herrero P, Markham J, Weinheimer CJ, Walsh MN. Noninvasive quantitation of myocardial blood flow in human subjects with oxygen-15-labeled water and positron emission tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;14:639–52. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90105-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schiller NB, Shah PM, Crawford M, DeMaria A, Devereux R, Feigenbaum H, et al. Recommendations for quantitation of the left ventricle by two-dimensional echocardiography. American Society of Echocardiography Committee on Standards, Subcommittee on Quantitation of Two-Dimensional Echocardiograms. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1989;2:358–67. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(89)80014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peterson LR, Waggoner AD, Schechtman KB, Meyer T, Gropler RJ, Barzilai B, et al. Alterations in left ventricular structure and function in young healthy obese women: assessment by echocardiography and tissue Doppler imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1399–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nielsen S, Guo Z, Albu JB, Klein S, O'Brien PC, Jensen MD. Energy expenditure, sex, and endogenous fuel availability in humans. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:981–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI16253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mittendorfer B, Patterson BW, Klein S. Effect of sex and obesity on basal VLDL-triacylglycerol kinetics. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:573–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.3.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mittendorfer B, Horowitz JF, Klein S. Gender differences in lipid and glucose kinetics during short-term fasting. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;281:E1333–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.281.6.E1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hatta H, Atomi Y, Shinohara S, Yamamoto Y, Yamada S. The effects of ovarian hormones on glucose and fatty acid oxidation during exercise in female ovariectomized rats. Horm Metab Res. 1988;20:609–11. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1010897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campbell SE, Febbraio MA. Effect of ovarian hormones on mitochondrial enzyme activity in the fat oxidation pathway of skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;281:E803–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.281.4.E803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matute ML, Kalkhoff RK. Sex steroid influence on hepatic gluconeogenesis and glucogen formation. Endocrinology. 1973;92:762–8. doi: 10.1210/endo-92-3-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kendrick ZV, Ellis GS. Effect of estradiol on tissue glycogen metabolism and lipid availability in exercised male rats. J Appl Physiol. 1991;71:1694–9. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.71.5.1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weiner CP, Lizasoain I, Baylis SA, Knowles RG, Charles IG, Moncada S. Induction of calcium-dependent nitric oxide synthases by sex hormones. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:5212–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.5212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lei B, Matsuo K, Labinskyy V, Sharma N, Chandler MP, Ahn A, et al. Exogenous nitric oxide reduces glucose transporters translocation and lactate production in ischemic myocardium in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:6966–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500768102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Recchia FA, McConnell PI, Loke KE, Xu X, Ochoa M, Hintze TH. Nitric oxide controls cardiac substrate utilization in the conscious dog. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;44:325–32. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00245-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beyer ME, Yu G, Hanke H, Hoffmeister HM. Acute gender-specific hemodynamic and inotropic effects of 17beta-estradiol on rats. Hypertension. 2001;38:1003–10. doi: 10.1161/hy1101.093422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Collins P, Rosano GM, Sarrel PM, Ulrich L, Adamopoulos S, Beale CM, McNeill JG, Poole-Wilson PA. 17 beta-Estradiol attenuates acetylcholine-induced coronary arterial constriction in women but not men with coronary heart disease. Circulation. 1995;92:24–30. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pedersen SB, Bruun JM, Kristensen K, Richelsen B. Regulation of UCP1, UCP2, and UCP3 mRNA expression in brown adipose tissue, white adipose tissue, and skeletal muscle in rats by estrogen. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;288:191–7. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nuutila P, Knuuti MJ, Maki M, Laine H, Ruotsalainen U, Teras M, et al. Gender and insulin sensitivity in the heart and in skeletal muscles. Studies using positron emission tomography. Diabetes. 1995;44:31–6. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li J, Stillman JS, Clore JN, Blackard WG. Skeletal muscle lipids and glycogen mask substrate competition (Randle cycle) Metabolism. 1993;42:451–6. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(93)90102-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Magkos F, Patterson BW, Mittendorfer B. No effect of menstrual cycle phase on basal very low density lipoprotein triglyceride and apolipoprotein B-100 kinetics. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006 doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00246.2006. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Erbel R, Schweizer P, Henn G, Meyer J, Effert S. Apical two-dimensional echocardiography: normal values for single and bi-plane determination of left ventricular volume and ejection fraction. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1982;107:1872–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1070223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]