Summary

Catalytically active, recombinant fusion proteins of bacteriophage E endosialidase were expressed and purified from Escherichia coli. Constructs with different fusion partners added to the amino terminus of the endosialidase were enzymatically active. A post-translational proteolytic cleavage was shown to occur between serine 706 and aspartate 707 to generate the 76 kDa mature enzyme from the 90 kDa translation product. Endosialidase truncated at the C-terminus from aspartate 707 was observed to have the same 76 kDa molecular weight as wild-type enzyme using denaturing SDS–PAGE but, under native PAGE conditions, was not observed to form the ≈250 kDa trimeric wild-type enzyme, implying that the C-terminus of the enzyme may be required for correct assembly of active trimer, rather than as part of the active site as has been previously suggested. Mutagenesis of aspartate 138 to alanine greatly reduced enzyme activity whereas conversion of other selected aspartate residues to alanine had less effect, consistent with similarities between the structure and catalytic mechanism of bacteriophage E endosialidase and those of exosialidases.

Introduction

Bacteriophage endosialidases hydrolyse internal α-2,8-linkages in polysialic acid (PSA), a polymer which may exceed 200 N-acetyl neuraminic acid (NeuNAc) residues, which comprises the capsular polysaccharide of Escherichia coli K1 and group B Neisseria meningitidis (Kasper et al., 1973; Jennings et al., 1977; Tomlinson and Taylor, 1985) and is also expressed at limited sites in vertebrates (Troy, 1992). They are of interest, not only because their substrate specificity and mode of action differ from exosialidases, but also because they have been suggested for use in the diagnosis and treatment of infections caused by bacteria expressing PSA as part of their capsule, especially K1 meningitis (Taylor, 1987), and used in the investigation of tumour metastasis (Scheidegger et al., 1994; Tanaka et al., 2000). The latter use derives from the observation that PSA is expressed on the neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) in a developmentally regulated manner (Finne et al., 1983) and plays a key role in the modulation of NCAM-mediated adhesion (Rutishauser, 1996; Rutishauser and Landmesser, 1996). PSA-NCAM is an oncodevelopmental marker in tumours of the human kidney and neuroendocrine cells (Roth et al., 1988; Figarella-Branger et al., 1990) and modulates neurite outgrowth in the developing vertebrate central nervous system (Rutishauser and Landmesser, 1996; Brusés and Rutishauser, 2000; Mahal et al., 2001; Marx et al., 2001). PSA has also been implicated in the process of metastasis of small cell and non-small cell lung carcinoma (Scheidegger et al., 1994; Tanaka et al., 2000). In addition, PSA has been observed on an unknown protein(s) produced by the metastatic human breast tumour cell line MCF7 (Martersteck et al., 1996).

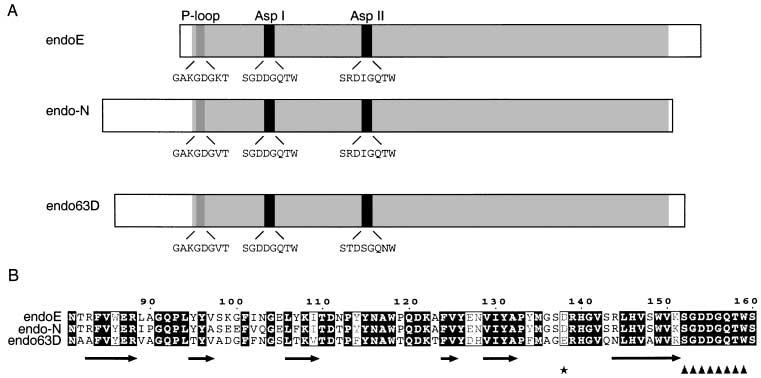

Much is known regarding the function and catalytic mechanism of exosialidases (Burmeister et al., 1992; Burmeister et al., 1994) and several crystal structures have been solved (Crennell et al., 1993; Crennell et al., 1994; Gaskell et al., 1995), including that of influenza neuraminidase, which has led to the design of therapeutically useful inhibitors (Wade, 1997; Colman, 1999; Kandel and Hartshorn, 2001). In contrast, there is little knowledge of the structure and function of endosialidases. Endosialidases require PSA of eight or more residues in length to catalyse internal hydrolysis (Pelkonen et al., 1989) and their mechanism of action contrasts with that of exosialidases, such as the α-2,3 or α-2,6 sialidases that remove the terminal sialic acid residues of many glycoproteins (Corfield, 1992). The genes encoding four K1 coliphage endosialidases have been cloned and sequenced. The predicted open reading frames (ORFs) of bacteriophage K1E endosialidase (also known as endoE and endoNE) (Gerardy-Schahn et al., 1995; Long et al., 1995), the virtually identical endosialidase from bacteriophage K1-5 (Scholl et al., 2001), bacteriophage K1F endosialidase (also known as endo-N) (Petter and Vimr, 1993) and the endosialidase from bacteriophage 63D (EMBL accession no. AB015437; Machida et al., 2000) all contain a central region of 690 amino acids with 47% identity. However, they differ considerably in their amino- and carboxy-terminal extensions (Fig. 1A). The region of greatest sequence identity contains two copies of the sialidase motif or asp-box (Roggentin et al., 1989; Rothe et al., 1991), which is conserved in many exosialidases from viral, bacterial and eukaryotic sources (Vimr et al., 1988; Hoyer et al., 1992; Ferrari et al., 1994) but also present in other protein families (Copley et al., 2001). In addition, the endoE sequence contains one copy of the P-loop motif (Walker et al., 1982), a common feature of nucleotide binding proteins that interacts with the phosphate groups of the bound nucleotide (Saraste et al., 1990), which is also found in some carbohydrate binding proteins (Luzio et al., 1997). There are closely related sequences in K1F endosialidase and 63D endosialidase. Apart from the sialidase motifs, the endosialidases share no obvious primary sequence similarity with the exosialidases.

Fig. 1.

The structure of endoE.

A. Schematic alignment of the endosialidases of known sequence, showing the relative positions and amino acid sequences of the P-loop and sialidase motifs (Asp I and Asp II). The region of high similarity between the enzymes is shaded in grey.

B. Secondary structure prediction for amino acids 81–160 of endoE and the equivalent regions of endo62D and endoF. The endoE residue number is indicated above the sequence and the predicted secondary structure beneath (see Experimental procedures). Predicted beta strands are denoted by arrows. The first sialidase motif (Asp I) is indicated by triangles. Asp138 is asterisked.

In this paper, we describe the bacterial expression of catalytically active endoE and provide evidence for post-translational processing of the enzyme to remove a 105-amino-acid carboxy-terminal fragment within the bacterial cytosol. This post-translational processing is not required for the enzyme to be catalytically active. We have also carried out mutagenesis studies that have shown that the P-loop motif is not necessary for catalytic function, and have provided data consistent with a role for the sialidase motifs in the stabilization of the tertiary structure of the enzyme, as suggested for exosialidases on the basis of structural studies (Crennell et al., 1994; Gaskell et al., 1995). The effect of mutation of the first aspartate residue (Asp 138) upstream of the first sialidase motif suggests a role in catalysis.

Results

Expression of catalytically active recombinant endoE

The endoE ORF was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), using the previously cloned full-length DNA (Long et al., 1995) as a template, ligated into the pGEX-2T vector and the glutathione-S-transferase (GST) fusion protein expressed, as described in Experimental procedures. Primers for PCR were as described in Table 1. Approximately 2 mg of GST–endoE fusion protein were purified from each litre of bacterial culture. Figure 2A shows the SDS–PAGE profiles of purified GST–endoE fusion protein (lane 1) and endoE with the 26 kDa GST domain removed by thrombin cleavage (lane 2). These proteins migrated with apparent molecular weights of 102 and 76 kDa respectively. The latter is consistent with the size reported for the bacteriophage-derived enzyme (Tomlinson and Taylor, 1985; Long et al., 1995), is clearly smaller than 90 kDa, the size of the predicted ORF; (Gerardy-Schahn et al., 1995; Long et al., 1995), and is consistent with the results of earlier in vitro transcription/translation studies (Long et al., 1995), which suggested that endoE was initially expressed as a 90 kDa polypeptide that was cleaved post-translationally towards the carboxy terminus to give the mature protein.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primer sequences.

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence | Application |

|---|---|---|

| JMB1 | 5′-CCGGGGATCCATGATTCAAAGACTAGGTTCTTCATTA-3′ | Cloning into pGEX-2T |

| JMB2 | 5′-CACAGAATTCTATGTGTTCTGGCGTGCAGCAGATTGC-3′ | Cloning into pGEX-2T |

| JMB20 | 5′-GGAATTCAATGATTCAAAGACTAGGTTCTTCA-3′ | Cloning into pMALp2 |

| JMB21 | 5′-ACGACGTGCGGTCTTGTGTATAGATCTCG-3′ | Cloning into pMALp2 |

| pQE30–5′ | 5′-CCGGGGATCCATTCAGAAAGACTAGGTTCTTCATTA-3′ | Cloning into pQE30 |

| pQE16–3′ | 5′-GAAGATCTACTGATTTTATTAGTGGCATACATCTC-3′ | Cloning into pQE16 |

| JMB9 | 5′-GGCGGCGGCGGCGGCGGCGGCGGCAAAATCTTTAAGCGATACAACCTCGGTGAG-3′ | ΔP-loop mutagenesis |

| JMB10 | 5′-GCCGCCGCCGCCGCCGCCGCCGCCAACGACCAAGATGCAGTAAATGCAGCGATG-3′ | ΔP-loop mutagenesis |

| JMB14 | 5′-AGCGGCCGCTGCCGCTGCGGCAGCCTTAACCCATGATACATGCAGACG-3′ | ΔAspI mutagenesis |

| JMB15 | 5′-GCTGCCGCAGCGGCAGCGGCCGCTTCTACTCCAGAGTGGTTAACTGAT-3′ | ΔAspI mutagenesis |

| JMB16 | 5′-AGCGGCCGCTGCCGCTGCGGCAGCACGATGCAGAGAGCTTCCTAGTC-3′ | ΔAspII mutagenesis |

| JMB17 | 5′-GCTGCCGCAGCGGCAGCGGCCGCTGAGTCACTAAGATTTCCACATAATGT-3′ | ΔAspII mutagenesis |

| JMB24 | 5′-TTTTGGATCCAACGACCAAGATGCAGTAAATGCAG-3′ | N-terminal truncation (Trunc45N) |

| D154A-I | 5′-GACCATCGGCGCCAGACTTAACCCAT-3′ | D154A mutagenesis |

| D154A-II | 5′-AAGTCTGGCGCCGATGGTCAAACATG-3′ | D154A mutagenesis |

| D402A-I | 5′-CTGACCTATAGCTCTACTACGATG-3′ | D402A mutagenesis |

| D402A-II | 5′-CGTAGTAGAGCTATAGGTCAGACT-3′ | D402A mutagenesis |

| G153A-I | 5′-ACCATCGACAGCAGACTTAACCCA-3′ | G153A mutagenesis |

| G153A-II | 5′-GTTAAGTCTGCTGACGATGGTCAA-3′ | G153A mutagenesis |

| W159A-I | 5′-CTGGAGTAGACGCTGTTTGACCA-3′ | W159A mutagenesis |

| W159A-II | 5′-TCAAACAGCGTCTACTCCAGAGT-3′ | W159A mutagenesis |

| D138A-I | 5′-ACCATGACGGGCGCTACCCAT-3′ | D138A mutagenesis |

| D138A-II | 5′-GGTAGCGCCCGTCATGGTGTT-3′ | D138A mutagenesis |

The names, sequences and applications of the oligonucleotide PCR primers used in the present study and referred to in the text are listed.

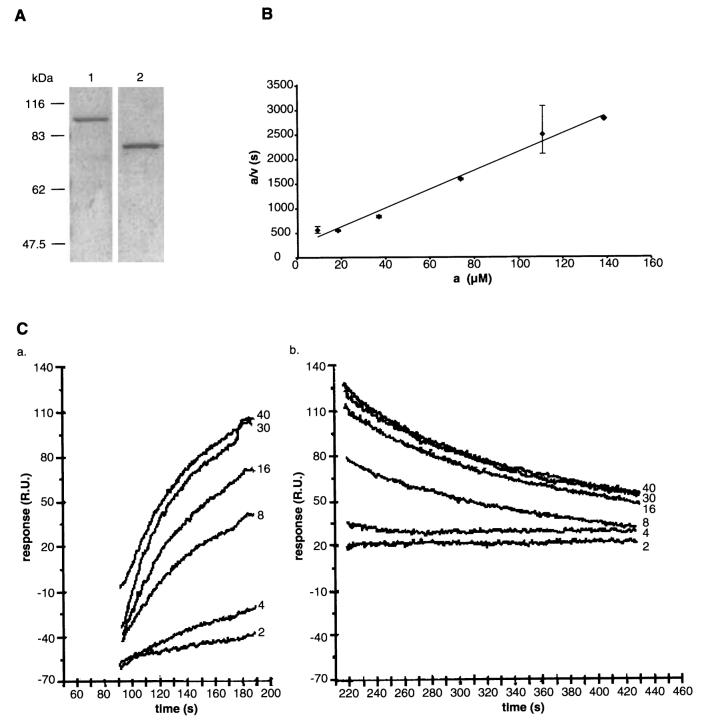

Fig. 2.

Expression of functional recombinant GST-endoE.

A. 10% SDS–PAGE showing purified GST–endoE fusion protein (1) and endoE after the GST domain had been removed by thrombin cleavage (2).

B. A representative a/v against a plot obtained by digesting a range of concentrations of PSA with 0.4 μg GST–endoE fusion protein. a, substrate concentration, μM; v, initial rate, μM/s.

C. The association (a) and the dissociation (b) regions of the curves of PSA binding to the immobilized fusion protein. For clarity, curves for only six of the PSA concentrations used and only those regions used in the calculation of the association and dissociation rate constants have been shown. The PSA concentration (μM) for each association and dissociation curve is indicated (2–40 μM). RUs are refractance units (see Experimental procedures). A time-frame of 226.5–298.5 s was used to calculate the dissociation rate constant and 96–167 s for the association rate constant.

The catalytic activities of purified GST–endoE and of thrombin-cleaved endoE were measured with PSA as substrate, and were proportional to the concentration of protein (data not shown). Kinetic characteristics were determined by measuring initial velocities at different substrate concentrations. Figure 2B shows a representative a/v against v plot of the enzyme activity of GST–endoE, from which the KM, kcat and kcat/KM values were calculated. These are shown in Table 2. There was no difference in any of these kinetic constants when either thrombin-cleaved endoE or His6-tagged endoE (see below) was used (data not shown). The mean value for the KM of recombinant GST–endoE was 17.7 – 4.2 μM (n = 8) and was similar to that obtained for the bacteriophage-derived enzyme (Long et al., 1995).

Table 2.

The catalytic properties of wild-type and mutated endosialidase fusion proteins.

| Construct | KM(μM) | kcat(s−1) | kcat/KM(M−1 s−1) × 103 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | 17.7 − 4.2 | 1.5 − 0.4 | 116.5 − 28.0 |

| ΔP-loop | 27.1 | 1.4 | 51.6 |

| Trunc N45 | 3.7 | 0.5 | 135.1 |

| ΔAspI | Insoluble | ||

| ΔAspII | Insoluble | ||

| G153A | 17.7 − 1.0 | 1.0 − 0.01 | 54.1 − 3.2 |

| D154A | 6.4 | 1.2 | 187.5 |

| W159A | Insoluble | ||

| D138A | 8.3 | 0.2 | 24.1 |

Each construct was expressed as a GST fusion protein. The catalytic properties of the enzymes were determined as described in the text. Values are mean − SEM for wild type (eight samples), mean − range for G153A (duplicates) or single estimations. All values for the kinetic parameters of mutants are within the range of values observed with wild-type enzyme.

The binding of PSA to GST–endoE was studied by surface plasmon resonance and dissociation rate constants (kDa) were determined as described in Experimental procedures. Sensorgrams from one experiment are shown in Fig. 2C. The dissociation rate constant, kDa, was calculated to be 4.37 – 0.19 × 10−3 s−1 (n = 16). This figure was used to calculate the association rate constant ka of 1.26 × 103 − 0.18 M−1 s−1 (n = 16) and the equilibrium dissociation constant KD of 3.47 μM.

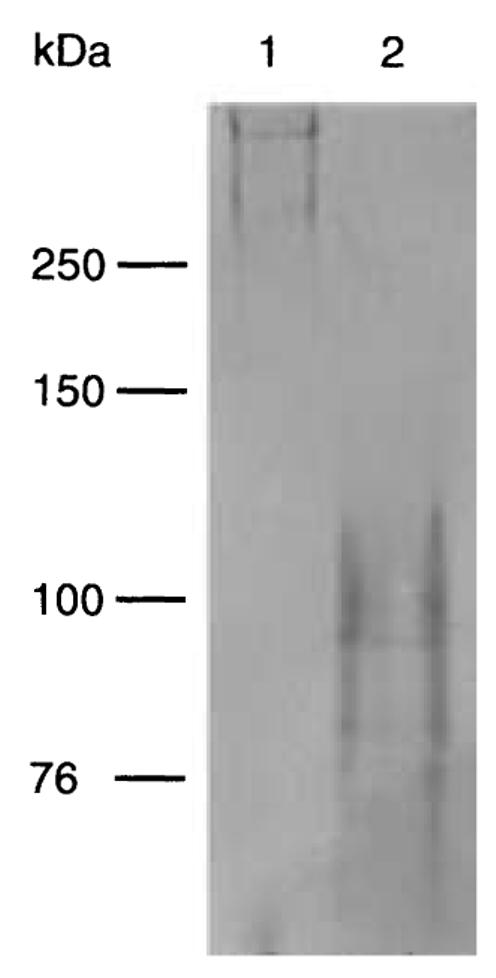

Post-translational proteolysis of endoE occurs between S706 and D707 to give the mature protein but is not essential for catalytic activity

Further evidence for carboxy-terminal processing was obtained by expressing His6-tagged endoE. When a vector encoding the His6-tag at the predicted amino terminus of endoE was used, expression of endoE of the predicted mature molecular weight was demonstrated by immunoblotting with anti-endoE antiserum (Fig. 3, lane 1) or anti-His5 monoclonal antibodies (Fig. 3, lane 5). In contrast, when a vector encoding the His6-tag at the predicted carboxy terminus of endoE was used, no expressed 76 kDa endoE was observed by immunoblotting with anti-His5 (Fig. 3, lane 6), yet it was detected by immunoblotting with anti-endoE (Fig. 3, lane 2). No mature endoE could be purified by immobilized nickel affinity chromatography when the carboxy-terminal His6-tag was used, however, a ≈14 kDa fragment was captured. Sequencing of this fragment from its amino terminus gave the amino acid series DADHYKGISSIN. This aligns with the predicted endoE amino acid sequence between D707 and N718, and suggests that the cleavage event occurs immediately before D707. Replacement of S706 and D707 with alanines by site-directed mutagenesis resulted in an enzymatically active protein with a molecular weight consistent with that expected from the full length ORF (Fig. 3, lanes 3 and 7)

Fig. 3.

Immunoblotting of His6-tagged endoE and MBP–endoE.

A. Immunoblot of endoE fusion proteins following 10% SDS–PAGE using rabbit antiendosialidase primary antibody.

B. Immunoblot of endoE fusion proteins following 10% SDS–PAGE using mouse anti-His5. The size of molecular weight markers is indicated on the left of the figure. Lanes 1 and 5 show endoE with a His6-tag encoded at the amino terminus. Lanes 2 and 6 show endoE with a His6-tag encoded at the carboxy terminus. Lanes 3 and 7 show the double S706A D707A mutant with a carboxy-terminal His6 tag. Lane 4 shows endoE with MBP at the amino terminus.

It has been suggested that the carboxy-terminal portion of endoE may be necessary for endosialidase activity (Gerardy-Schahn et al., 1995) and that a region of sequence similarity in an endo-β-eliminase is required for enzyme activity (Legoux et al., 1996). As in the above experiments we could not rule out a proteolytically cleaved fragment remaining associated with the mature enzyme, a GST-tagged truncation construct (Trunc 105C) was made in which 105 amino acids were removed from the predicted carboxy terminus. The resulting enzyme was found to be largely insoluble. SDS–PAGE of the soluble fraction showed the molecular weight to be 102 kDa, similar to recombinant GST-tagged, wild-type enzyme (data not shown), and the same molecular weight was observed if the protein was electrophoresed under non-denaturing conditions (Fig. 4, lane 2). This contrasts with wild-type enzyme, which has an observed molecular weight of ≈250 kDa when electrophoresed under non-denaturing conditions (Fig. 4, lane 1), consistent with it being a trimer. Taken together, these data suggest that the C-terminal 105 amino acids of endoE may be required for the correct assembly of the enzyme trimer and are not directly a part of the active site as has been previously suggested (Gerardy-Schahn et al., 1995).

Fig. 4.

Non-denaturing electrophoresis of full-length and truncated endoE. Non-denaturing 7.5% PAGE showing GST–endoE (lane 1) and GST–trunc105 (lane 2).

In addition to GST- and His6-tagged fusion proteins of endoE, we also prepared a fusion protein with maltose binding protein (MBP) attached at the predicted amino terminus of the enzyme. When this was expressed, it was enzymatically active and had a molecular weight consistent with expression of the full length endoE ORF (Fig. 3, lane 4). Fusion proteins with MBP attached at the amino terminus are secreted into the periplasmic space by virtue of the leader peptide attached to the MBP (diGuan et al., 1988). As the GST–endoE and His6–endoE, but not MBP–endoE, appeared to have been processed at the carboxy terminus, we suggest that post-translational modification occurs as a result of cytosolic proteolytic activity that is not present in the periplasmic space. The data also show that post-translational modification at the carboxy terminus is not necessary for endoE activity.

Mutations of the P-loop, sialidase motifs and aspartate residues upstream of the first sialidase motif

Residues 38–45 of the predicted amino acid sequence of endoE (Fig. 1A) match the consensus sequence for the P-loop motif (Walker et al., 1982; Long et al., 1995), and we have previously described database homology searches, which revealed a similar sequence motif in a number of other carbohydrate-binding proteins (Luzio et al., 1997). To determine the importance of this region of the protein in PSA binding and hydrolysis, the residues of the P-loop motif were replaced by alanines (the ΔP-loop construct). This resulted in expression of a GST–endoE fusion protein that retained wild-type catalytic properties, with very similar KM, kcat and kcat/KM values (Table 2). Further evidence for the lack of requirement for the P-loop was obtained by constructing a truncation mutant (Trunc 45 N) in which the first 45 amino acids were removed from the predicted amino terminus. The resultant GST fusion protein was also catalytically active (Table 2).

Sialidase motifs are a common feature of many sialidases (Taylor, 1996) and there has been speculation that they may play a role in catalysis (Roggentin et al., 1989). To determine whether the two sialidase motifs of endoE (Fig. 1A) were involved in substrate binding or catalysis, we carried out mutagenesis of each. Replacement of all eight residues of either sialidase motif with eight alanine residues (ΔAsp I and ΔAsp II) rendered the resultant GST–endoE fusion proteins insoluble such that they could not be purified without denaturation (Table 2). Mutation of the conserved tryptophan in the first sialidase motif (W159A), caused the fusion protein to become totally insoluble. In contrast, mutation of the non-conserved glycine in the first motif (G153A) affected neither the solubility of the enzyme nor its catalytic activity (Table 2). Mutation of the conserved aspartate to alanine in either of the sialidase motifs (D154A or D402A) markedly decreased (≈80%) the solubility of the fusion proteins but the soluble recombinant enzyme had very similar KM, kcat and kcat/KM values to the wild-type enzyme (Table 2 and data not shown).

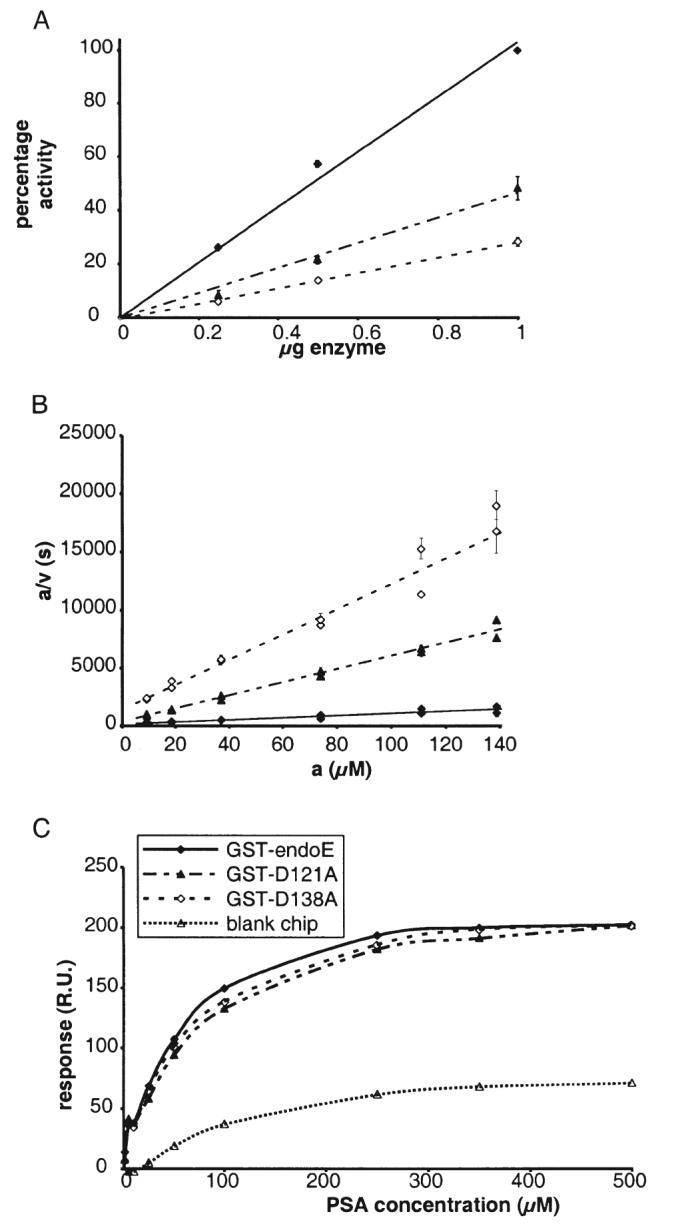

The P-loop motif and the two sialidase motifs were the most obvious targets for mutagenesis studies of endoE, but as we could find no evidence that either was directly involved in the catalytic mechanism of endoE, another approach was taken to identify residues involved in catalysis. If the mechanism of glycosidic bond cleavage by endoE is similar to that used by the exosialidases, then it might be expected that the knowledge of the active site residues gained from structural studies of these enzymes could be used to predict endoE residues involved in binding and/or catalysis. In the exosialidases for which crystal structures are available (Burmeister et al., 1992; Crennell et al., 1993; 1994; Gaskell et al., 1995), there is an aspartate residue that occurs between the second and third strands of the first β-sheet in the catalytic domain, upstream of the sialidase motif, that is thought to stabilize a proton-donating water molecule involved in bond hydrolysis (Burmeister et al., 1993; Gaskell et al., 1995). The predicted secondary structure of the endoE sequence (Fig. 1B) suggests that the equivalent aspartate residue upstream of the first sialidase motif is Asp138. This aspartate residue was mutated to alanine (D138A) and the resultant expressed GST–endoE fusion protein was assessed for solubility and catalytic activity. It was found to be ≈80% soluble with respect to wild type but had approximately 20% wild-type activity (Fig. 5A). The CD spectrum of the soluble mutated GST–endoE showed no significant difference to that of wild-type GST–endoE, implying that the soluble mutated enzyme was correctly folded (data not shown). The KM and the ability to bind PSA of this mutated enzyme were found to be similar to GST-wild-type enzyme (Fig. 5B and C; Table 2) but the kcat was reduced 12-fold. Mutagenesis of Asp138 to Val or Asn also resulted in GST–endoE fusion proteins with activities similar to that of the D138A construct (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Enzymatic activity, kinetics and PSA binding of GST–endoE, GST–D121A and GST–D138A.

A. A plot showing the relative activities of GST–D121A (▲), GST-D138A (◇) and GST-endoE (◆) as a percentage of the activity measured for 1 μg GST–endoE.

B. a/v against a plot from two experiments measuring the endosialidase activity of 1 μg of recombinant GST–D121A (▲), GST-D138A (◇) and GST–endoE (◆, recalculated from the data in Fig. 2 for comparison) against a range of polysialic acid concentrations. a, substrate concentration, μM; v, initial rate, μM/s.

C. A plot showing the increase in surface plasmon resonance response units due to binding of varying concentrations of PSA to immobilized GST–D121A (▲), GST-D138A (◇) and GST-endoE (◆). Non-specific binding of PSA to a blank chip is depicted by open triangles (Δ).

Discussion

We have obtained functional expression of endoE using three different amino-terminal fusion systems. Previous attempts to express the related K1F endosialidase as a fusion protein were unsuccessful (Petter and Vimr, 1993). Gerardy-Schahn and colleagues (Gerardy-Schahn et al., 1995) described the bacterial expression of endoE with a carboxy-terminal His6-tag. These workers reported that bacterial lysates containing the recombinant enzyme were able to remove PSA from NCAM, as demonstrated by the loss of immunoreactivity towards an anti-PSA monoclonal antibody. A truncation of 38 amino acids from the C-terminus of the enzyme was shown to prevent the loss of anti-PSA immunoreactivity, and led to the suggestion that the C-terminal 38 amino acids were required for enzymatic activity. The difference in the apparent molecular weight of the enzyme from that predicted from the ORF was judged to be due to the acidity of the enzyme. The results presented here show that in fact the difference between observed and predicted molecular weights of endoE is due to a post-translational cleavage between serine 706 and aspartate 707, shortening the protein by 105 amino acids from the C-terminus. In this study, the Trunc 105C enzyme was largely insoluble in comparison with the wild-type enzyme. However, the small amount of soluble protein that could be purified did not assemble into trimers. Failure to trimerize may also explain the apparent loss of activity of the 38-amino-acid truncated enzyme reported by Gerardy-Schahn and colleagues (Gerardy-Schahn et al., 1995), rather than the direct involvement of the C-terminal amino acids in the active site. The published data on the K1F endosialidase (endo-N) which does not have a region of sequence similar to the C-terminal region of endoE (see Fig. 1A) are consistent with this hypothesis. The assembly of endoE into a trimer is consistent with the known location of endoE in the tail spike of bacteriophage K1E, in which it is likely to interact with other capsular proteins.

In the present study, enzyme activity was measured by quantifying the release of reducing sugar termini during the cleavage of PSA by endoE. Using this assay, GST–endoE was determined to have a KM very similar to that previously reported for the coliphage-derived enzyme (Long et al., 1995). Interpretation of the kinetic characteristics in relation to other glycosidases is complicated by the nature of the reaction catalysed by the endosialidase. First, because the substrate is polymeric, one PSA chain may contain many potential binding and cleavage sites along its length so that the effective substrate concentration may be higher than that estimated. Second, cleavage of a PSA polymer could generate two, smaller PSA polymers, which would still serve as endoE substrates. Lastly, the affinity of endosialidases for smaller sialyl oligomers is known to be less than that for longer chains (Pelkonen et al., 1989). However, the assay does allow comparison of the catalytic properties of mutated endoE fusion proteins with those of the wild-type enzyme. The data from the surface plasmon resonance study of the binding interaction between PSA and endoE gave a mean value for the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) of 3.38 × 10−6 M. Both the KD and the KM (17.7 × 10−6 M) for the enzyme lie in the micromolar range, suggesting that the turnover rate of the enzyme is governed primarily by the binding of substrate to enzyme rather than by bond hydrolysis.

Mutagenesis of the P-loop residues and the two sialidase motifs in endoE did not affect the catalytic properties of the enzyme when soluble enzyme was produced, indicating that these regions of the protein are unlikely to be directly involved in PSA binding or hydrolysis. As the amino-terminal region of endoE, including the P-loop, has weak sequence similarity with other bacteriophage tail spike proteins (Long et al., 1995), it may play a role in attachment of the endosialidase to other components of the tail spike assembly in bacteriophageE. The results of the mutagenesis of the two siali-dase motifs, summarized in Table 2, suggest that the principal effect of altering conserved residues within the motif is to alter the solubility of the protein. The data are consistent with a mutagenesis study of the Clostridium perfringens exosialidase (Chien et al., 1996), in which mutation of residues within the siali-dase motifs did not significantly affect catalytic activity per se. They are also consistent with the suggestion that the sialidase motifs are important in maintaining the correct fold structure in the sialidase protein family (Crennell et al., 1994; Gaskell et al., 1995) rather than the earlier suggestion that they may be important in catalytic function (Roggentin et al., 1989). The crystal structures of the sialidases of Salmonella typhimurium and Micromonospora viridifaciens indicate that the conserved residues of the sialidase motif form an intraloop hydrogen bond network. This being the case, replacement of a negatively charged aspartate with an alanine would disrupt the hydrogen bond network and hence the structural integrity of the protein. It is therefore likely that the reduced solubility of the D154A and D402A mutants and the insolubility of the ΔAspI, ΔAspII and W159A mutants was due to the misfolding of the mutant proteins through disruption of the hydrogen bond network within the sialidase motifs. Certainly the replacement of the eight amino acids of each sialidase motif with alanine cannot lead to insolubility per se, as the equivalent substitution of the P-loop motif resulted in a soluble and fully active enzyme. Substitution of the non-conserved glycine with alanine (G153A), a very conservative mutation, would not be expected to have any effect on the motif structure and was observed to have no effect on solubility or enzyme activity.

PSA is known to undergo autohydrolysis in solution, particularly in mildly acidic conditions (Varki and Higa, 1993). A mechanism has been proposed to account for this in which the carboxylate group of one sialic acid residue acts as a general acid catalyst towards the ketosidic bond with the neighbouring residue, such that the reaction proceeds via an oxycarbonium ion intermediate (Manzi et al., 1994). It is possible that endoE catalyses PSA hydrolysis by essentially the same mechanism, acting as an acid catalyst and stabilizing an oxycarbonium ion intermediate. Such a model is compatible with the mechanism suggested for several exosialidases (Burmeister et al., 1993; Gaskell et al., 1995). The three dimensional structures of the exosialidases of influenza virus (Burmeister et al., 1992), S. typhimurium (Crennell et al., 1993), Vibrio cholerae (Crennell et al., 1994) and M. viridifaciens (Gaskell et al., 1995) have been solved. Although they share only minimal sequence similarity and the influenza virus siali-dase does not possess any sialidase motifs, all have identical fold topology and have many common features in their active centres (Gaskell et al., 1995). The catalytic domain of the sialidases is predominantly β-sheet consisting of six four-stranded antiparallel β-sheets arranged as in the blades of a propeller, a topology referred to as the ‘canonical neuraminidase fold’ (Crennell et al., 1994). The sialidase motifs always occur between the third and fourth strands of each β-sheet in which they are present (Crennell et al., 1993). The common active site residues of the exosialidases comprise three sequentially distant arginines, stabilizing the carboxylic acid group of sialic acid, a glutamate that stabilizes one of these arginines and a tyrosine and glutamate thought to stabilize the transition state of the reaction (Crennell et al., 1994; Gaskell et al., 1995). In addition, there is an aspartate residue that occurs between the second and third strands of the first β-sheet that may act to stabilize a proton-donating water molecule in bond hydrolysis (Burmeister et al., 1993; Gaskell et al., 1995). Consistent with this suggestion for exosialidases was the effect of mutation of the equivalent aspartate (to valine) in the C. perfringens exosialidase (Chien et al., 1996), which resulted in greatly decreased catalytic efficiency. Our data on the D138A mutant of endoE which had a >80% reduction in kcat/KM (and the reduced activity of the D138N and D138V mutants) suggest that this aspartate residue may perform a similar role in the endosialidase. A caveat is required because in the present experiments the yield of soluble protein was always reduced when expressing GST–endoE containing mutations to Asp138 compared with expression of wild-type protein. Thus, a function of Asp138 in protein folding and solubility cannot be ruled out. Only the crystal structure of the enzyme will provide proof of the residues involved in catalysis.

The results presented in this paper go some way to providing an understanding of the function of endoE and demonstrating its similarities and differences to exosialidases. We have shown that neither the conserved P-loop motif nor the sialidase motifs are involved in catalysis. Availability of functional recombinant enzyme opens up the possibility of developing such capsule-depolymerizing enzymes for use in treating bacterial infections and as a tool for studying PSA involvement in tumour function and metastasis.

Experimental procedures

Materials

Unless specified, all chemical reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. and were of analytical grade or equivalent. DNA modifying enzymes and restriction endonucleases were purchased from New England Biolabs (NEB). The pGEX, pMAL and pQE expression vectors were purchased from Pharmacia Biotech, NEB and Qiagen respectively. Oligonucleotides were synthesised by R and D systems.

Molecular biology

Molecular biology procedures were performed according to Sambrooke and colleagues (Sambrooke et al., 1989) unless otherwise stated. Wizard Plus SV miniprep kits (Promega) were used for high purity plasmid isolation and a Qiaex II kit (Qiagen) for purification of DNA from agarose gels. DNA sequencing was performed using a Sequenase Version 2.0 kit (USB/Amersham) and radiolabelled dATP (Amersham), or was obtained from the service provided by the Department of Biochemistry, University of Cambridge. Bacterial cells, Escherichia coli MC1061 or E. coli XL1-Blue MRF (Stratagene) were transformed by electroporation using a Bio-Rad (Hercules) gene pulser. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed using Vent DNA polymerase (NEB) and plasmid F15 described previously (Long et al., 1995) as template.

Expression cloning of endosialidase constructs

For cloning into pGEX-2T, endoE PCR products were digested with BamHI and EcoRI. PCR products were digested with EcoRI and XbaI for cloning into pMAL-p2; with BamHI and KpnI for cloning into pQE30 and with BamHI for cloning into pQE16. Mutated endoE PCR products were digested with BamHI and EcoRI and cloned into pGEX-2T.

Mutagenesis of the endoE ORF

Unless otherwise stated, site-directed mutagenesis was performed by PCR using the technique of overlap extension (Higuchi, 1989). The synthetic oligonucleotides used for each mutation are listed in Table 1 and were used in conjunction with the two external primers, JMB1 and JMB2. Truncation mutants were also generated by PCR. Site-directed mutagenesis of Asp138 to Asn or Val was carried out using the Strategene QuikChange kit according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Bacterial transformation and expression of recombinant fusion proteins

Plasmids were transformed into E. coli XL1-Blue by electroporation and checked for the correct insert using DNA sequencing. Expression of fusion proteins was carried out by growing bacteria in 500 ml shake-flask cultures to an A600 of 0.2 and inducing with 0.1 mM IPTG. The induced bacteria were then grown at 30°C overnight, harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 145 mM NaCl, 7.5 mM Na2HPO4, 2.5 mM NaH2PO4, pH 7.4) and lysed by sonication. The lysate was then clarified by centrifugation to pellet insoluble matter.

Protein purification and sequencing

Glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-fusion proteins were purified using glutathione-affinity chromatography of the PBS-soluble fraction of sonicated bacterial extracts according to the manufacturer's directions (Pharmacia Biotech). When carried out, thrombin cleavage of the eluted fusion protein was performed at room temperature with 1 NIH unit of thrombin per mg of fusion protein for 16 h in the elution buffer with the addition of CaCl2 to 1 mM. Typically, 95% cleavage was achieved. Maltose binding protein (MBP)-fusion protein and His6-tagged fusion protein were purified similarly from the soluble fraction according to the manufacturer's instructions using amylose affinity chromatography for the MBP-fusion proteins (NEB) and Ni-NTA affinity chromatography for the His6-tagged fusion protein (Qiagen). N-terminal microsequencing of a carboxyterminally His6-tagged proteolytic fragment of endoE was conducted at the Babraham Institute, Cambridge, UK, as previously described (Long et al., 1995).

Analytical assays

Polysialic acid (PSA) for use as a substrate for measuring endosialidase activity was prepared using an adaptation of the method of Pelkonen and colleagues (Pelkonen et al., 1988). Escherichia coli strain LP1674 (serotype O7:K1) (Tomlinson and Taylor, 1985) was grown for 16 h at 37°C and pelleted by centrifugation. The pellet was then washed twice in cold PBS and once with cold 0.1 M pyridine-acetate buffer pH 5.0. The bacteria were incubated in 0.1 volumes of 0.1 M pyridine-acetate buffer pH 5.0 for 1 h at 37°C with intermittent gentle shaking and then pelleted by centrifugation. PSA was precipitated from the supernatant by the addition of 10 volumes of cold ethanol and incubating at 4°C overnight. The precipitate was centrifuged at 10 000 g for 10 min, redissolved in a minimum volume of water and lyophilized. PSA for the kinetic analysis using surface plasmon resonance was produced using an adaption (Tomlinson and Taylor, 1985) of the phenol–water extraction method described by Westphal and Jann (1965).

Endosialidase activity was assayed as described previously (Horgan, 1982; Long et al., 1995) by measuring the release of reducing termini from PSA by a colorimetric method after incubation with the enzyme. Calculations of the kinetic parameters of the enzyme activity were made using the assumptions that the substrate molecular weight was 54 000 Da, equivalent to a mean polymer length of 175 residues (Hallenbeck et al., 1987) and that the monomer molecular weight of wild-type endoE was 76 000 Da. KM values were calculated from linear a/v against a graphical plots (Cornish Bowden and Wharton, 1988), in which ‘a’ represents substrate concentration and v, initial rate. Protein concentration was determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay reagent with dilutions of bovine serum albumin (BSA) serving as standards.

SDS–PAGE, non-denaturing gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting

SDS–PAGE (Laemmli, 1970) and immunoblotting (Burnette, 1981) were carried out essentially as described. Non-denaturing PAGE was carried out using a 7.5% resolving gel and 4% stacking gel using the same methods as SDS–PAGE except for the omission of SDS from the buffers used. Samples were mixed with equal volume of 2× non-denaturing sample buffer (160 mM Tris-Cl pH 6.8, 20%(w/v) glycerol, 0.01%(w/v) bromophenol blue) and heated at 37°C for 5 min. Gels were run at 150 V for 4 h at room temperature. After both SDS–PAGE and non-denaturing PAGE, protein bands were visualized by staining with Coomassie brilliant blue. Nitrocellulose immunoblots were incubated with 1:1000 rabbit anti-endoE serum (Long et al., 1995), or mouse anti-His5 IgG (Qiagen) for 75 min at room temperature followed by 1:4000 alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG or anti-mouse IgG for 1 h at room temperature before colour development with NBT/BCIP.

Surface plasmon resonance

Surface plasmon resonance studies were performed using a Biacore 2000 biosensor system (Pharmacia biosensor; Jönsson et al., 1991); 2033 refractance units of GST–endoE fusion protein were immobilized on a research grade CM5 chip using the amine coupling kit as directed by the manufacturer (1 refractance unit corresponding to approximately 1 pgmm−2; Stenberg et al., 1991). Kinetic analysis was performed at 25°C with a flow rate of 20 μl min−1. Binding of PSA, prepared by the phenol–water extraction method described above, to the immobilized protein or to a blank CM5 chip, was measured at concentrations of 0–40 μM PSA. All measurements were performed in Hepes-buffered saline (10 mM Hepes pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 3.4 mM EDTA, 0.005% surfactant P20) and the CM5 chip surfaces were regenerated with 5 ml of 0.05% SDS.

Association and dissociation rate constants were calculated by non-linear fitting of the primary sensorgram data (O'Shannessy et al., 1993) using the biaevaluation 2.0 software (Pharmacia biosensor) as described elsewhere (MacKenzie et al., 1996). The data were submitted to the validity tests suggested by Schuck and Minton (1996) and seen to be internally consistent.

Statistics

When appropriate, data are presented as the mean value ± SEM with the number of observations indicated in brackets.

Secondary structure prediction

Prediction of the secondary structure of the endoE sequence was made using the program jpred, available at http://jura.ebi.ac.uk:8888/ (Cuff et al., 1998). In a test of 396 protein domain sequences, this program achieved 72.9% accuracy and was the best out of seven programs tested; see http://jura.ebi.ac.uk:8888/acc.html (Cuff and Barton, 1999).

Acknowledgements

D.R.L. and J.M.B. held Medical Research Council collaborative studentships. This work was funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Horsham, UK, and the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. The Cambridge Institute for Medical Sciences is in receipt of a strategic award from the Wellcome Trust. We thank Ian Matthews for help with the collection and analysis of surface plasmon resonance data and Sally Gray for preparing some of the mutated endoE constructs.

References

- Brusés JL, Rutishauser U. Polysialic acid in neural development: roles, regulation and mechanism. In: Fukuda M, Hindsgaul O, editors. Molecular and Cellular Glycobiology. Oxford, UK and New York, USA: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 116–132. [Google Scholar]

- Burmeister WP, Ruigrok RW, Cusack S. The 2.2 Å resolution crystal structure of influenza B neuraminidase and its complex with sialic acid. EMBO J. 1992;11:49–56. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05026.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burmeister WP, Henrissat B, Bosso C, Cusack S, Ruigrok RWH. Influenza B virus neuraminidase can synthesize its own inhibitor. Structure. 1993;1:19–26. doi: 10.1016/0969-2126(93)90005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burmeister WP, Cusack S, Ruigrok RW. Calcium is needed for the thermostability of influenza B virus neuraminidase. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:381–388. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-2-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnette WN. ‘Western blotting’: electrophoretic transfer of proteins from sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels to unmodified nitrocellulose and radiographic detection with antibody and radioiodinated protein A. Anal Biochem. 1981;112:195–203. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien CH, Shann YJ, Sheu SY. Site-directed mutations of the catalytic and conserved amino acids of the neuraminidase gene, nanH, of Clostridium perfringens ATCC 10543. Enz Microb Technol. 1996;19:267–276. doi: 10.1016/0141-0229(95)00245-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colman PM. A novel approach to antiviral therapy for influenza. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;44(Suppl. B):17–22. doi: 10.1093/jac/44.suppl_2.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copley RR, Russell RB, Ponting CP. Sialidase-like Asp-boxes: sequence-similar structures within different protein folds. Protein Sci. 2001;10:285–292. doi: 10.1110/ps.31901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corfield T. Bacterial sialidases-roles in pathogenicity and nutrition. Glycobiology. 1992;2:509–521. doi: 10.1093/glycob/2.6.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornish Bowden A, Wharton CW. Enzyme Kinetics. Oxford, UK: IRL Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Crennell S, Garman E, Laver G, Vimr E, Taylor G. Crystal-structure of a bacterial sialidase (from Salmonella typhimurium lt2) shows the same fold as an influenza-virus neuraminidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9852–9856. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.9852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crennell S, Garman E, Laver G, Vimr E, Taylor G. Crystal-structure of vibrio-cholerae neuraminidase reveals dual lectin-like domains in addition to the catalytic domain. Structure. 1994;2:535–544. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuff JA, Barton GJ. Evaluation and improvement of multiple sequence methods for protein secondary structure prediction. Proteins. 1999;34:508–519. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(19990301)34:4<508::aid-prot10>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuff J, Clamp ME, Siddiqui AS, Finlay M, Barton GJ. JPred: a consensus secondary structure prediction server. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:892–893. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.10.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari J, Harris R, Warner TG. Cloning and expression of a soluble sialidase from Chinese hamster ovary cells: sequence alignment similarities to bacterial sialidases. Glycobiology. 1994;4:367–373. doi: 10.1093/glycob/4.3.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figarella-Branger DF, Durbec PL, Rougon GN. Differential spectrum of expression of neural cell adhesion molecule isoforms and L1 adhesion molecules on human neuroectodermal tumors. Cancer Res. 1990;50:6364–6370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finne J, Finne U, Deagostini-Bazin H, Goridis C. Occurrence of alpha-2,8-linked polysialosyl units in a neural cell adhesion molecule. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1983;112:482–487. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(83)91490-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaskell A, Crennell S, Taylor G. The three domains of a bacterial sialidase: a beta-propeller an immunoglobulin module and a galactose-binding jelly-roll. Structure. 1995;3:1197–1205. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00255-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerardy-Schahn R, Bethe A, Brennecke T, Muhlenhoff M, Eckhardt M, Ziesing S, et al. Molecular-cloning and functional expression of bacteriophage-PK1E-encoded endoneuraminidase endo NE. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:441–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- diGuan C, Li P, Riggs PD, Inouye H. Vectors that facilitate the expression and purification of foreign peptides in Escherichia coli by fusion to maltose-binding protein. Gene. 1988;67:21–30. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallenbeck PC, Vimr ER, Yu F, Bassler B, Troy FA. Purification and properties of a bacteriophage-induced endo-N-acetylneuraminidase specific for poly-alpha-2,8-sialosyl carbohydrate units. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:3553–3561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi R. Using PCR to engineer DNA. In: Erlich HA, editor. PCR Technology: Principles and Applications for DNA Amplification. New York: Stockton Press; 1989. pp. 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Horgan IE. A modified spectrophotometric assay for determination of nanogram quantities of sialic acid. Clin Chim Acta. 1982;116:409–415. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(81)90062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer LL, Hamilton AC, Steenbergen SM, Vimr ER. Cloning, sequencing and distribution of the Salmonella typhimurium LT2 sialidase gene, nanH, provides evidence for interspecies gene transfer. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:873–884. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings HJ, Bhattacharjee AK, Bundle DR, Kenny CP, Martin A, Smith ICP. Structures of the capsular polysaccharides of Neisseria meningitidis as determined by 13C-nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Infect Dis. 1977;136:s78–s83. doi: 10.1093/infdis/136.supplement.s78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jönsson U, Fägerstam L, Ivarsson B, Johnsson B, Karlsson R, Lundh K, et al. Real-time biospecific interaction analysis using surface plasmon resonance and a sensor chip technology. Biotechniques. 1991;11:620–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel R, Hartshorn KL. Prophylaxis and treatment of influenza virus infection. Biodrugs. 2001;15:303–323. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200115050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper DL, Winkelhake JL, Zollinger WD, Brandt BL, Artenstein MS. Immunochemical similarity between polysaccharide antigens of Escherichia coli 07:K1(L):NM and group B Neisseria meningitidis. J Immunol. 1973;110:262–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legoux R, Lelong P, Jourde C, Feuillerat C, Capdevielle J, Sure V, et al. N-acetyl-heparosan lyase of Escherichia coli K5: gene cloning and expression. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:7260–7264. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.24.7260-7264.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long GS, Bryant JM, Taylor PW, Luzio JP. Complete nucleotide sequence of the gene encoding bacteriophage K1E endosialidase: implications for K1E endosialidase structure and function. Biochem J. 1995;309:543–550. doi: 10.1042/bj3090543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzio JP, Bryant MB, Taylor PW. Engineering proteins that bind to cell surface carbohydrates. Clin Chim Acta. 1997;266:13–22. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(97)00162-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machida Y, Miyake K, Hattori K, Yamamoto S, Kawase M, Iijima S. Structure and function of a novel coliphage-associated sialidase. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;182:333–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb08917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie CR, Hirama T, Deng S-J, Bundle DR, Narang SA, Young NM. Analysis by surface plasmon resonance of the influence of valence on the ligand binding affinity and kinetics of an anti-carbohydrate antibody. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:1527–1533. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.3.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahal LK, Charter NW, Angata K, Fukuda M, Koschland DE, Bertozzi CR. A small-molecule modulator of poly-α2,8-sialic acid expression on cultured neurons and tumor cells. Science. 2001;294:380–382. doi: 10.1126/science.1062192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzi AE, Higa HH, Diaz S, Varki A. Intramolecular self-cleavage of polysialic acid. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:23617–23624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martersteck CM, Kedersha NL, Drapp DA, Tsui TG, Colley KJ. Unique alpha 2,8-polysialylated glycoproteins in breast cancer and leukemia cells. Glycobiology. 1996;6:289–301. doi: 10.1093/glycob/6.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx M, Rutishauser U, Bastmeyer M. Dual function of polysialic acid during zebrafish central nervous system development. Development. 2001;128:4949–4958. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.24.4949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Shannessy DJ, Brigham-Burke M, Soneson KK, Hensley P, Brooks I. Determination of rate and equilibrium binding constants for macromolecular interactions using surface plasmon resonance: use of nonlinear least squares analysis methods. Anal Biochem. 1993;212:457–468. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelkonen S, Hayrinen J, Finne J. Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of the capsular polysaccharides of Escherichia coli K1 and other bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2646–2653. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.6.2646-2653.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelkonen S, Pelkonen J, Finne J. Common cleavage pattern of polysialic acid by bacteriophage endosialidases of different properties and origins. J Virol. 1989;63:4409–4416. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.10.4409-4416.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petter JG, Vimr ER. Complete nucleotide-sequence of the bacteriophage K1F tail. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4354–4363. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.14.4354-4363.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roggentin P, Rothe B, Kaper JB, Galen J, Laurisuk L, Vimr ER, Schauer R. Conserved sequences in bacterial and viral sialidases. Glycoconjugate J. 1989;6:349–353. doi: 10.1007/BF01047853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth J, Zuber C, Wagner P, Taatjes DJ, Weisgerber C, Heitz PU, et al. Reexpression of poly (sialic acid) units of the neural cell-adhesion molecule in wilms tumor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2999–3003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.9.2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothe B, Rothe B, Roggentin P, Schauer R. The sialidase gene from Clostridium septicum: cloning, sequencing, expression in Escherichia coli and identification of conserved sequences in sialidases and other proteins. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;226:190–197. doi: 10.1007/BF00273603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutishauser U. Polysialic acid and the regulation of cell interactions. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:679–684. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutishauser U, Landmesser L. Polysialic acid in the vertebrate nervous system: a promoter of plasticity in cell–cell interactions. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:422–427. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(96)10041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrooke J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: a Laboratory Manual. 2nd edn. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Saraste M, Sibbald PR, Wittinghofer A. The P-loop: a common motif in ATP- and GTP-binding proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1990;15:430–434. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(90)90281-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheidegger EP, Lackie PM, Papay J, Roth J. In vitro and in vivo growth of clonal sublines of human small-cell lung-carcinoma is modulated by polysialic acid of the neural cell-adhesion molecule. Laboratory Invest. 1994;70:95–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholl D, Rogers S, Adhya A, Merril CR. Bacteriophage K1–5 encodes two different tail fiber proteins, allowing it to infect and replicate on both K1 and K5 strains of Escherichia coli. J Virol. 2001;75:2509–2515. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.6.2509-2515.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuck P, Minton AP. Kinetic analysis of biosensor data: elementary tests for self-consistency. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:458–460. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(96)20025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenberg E, Persson B, Roos H, Urbaniczky C. Quantitative determination of surface concentration of protein with surface plasmon resonance by using radiolabeled proteins. J Colloid Interface Sci. 1991;143:513–526. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka F, Otake Y, Nakagawa T, Kawano Y, Miyahara R, Li M, et al. Expression of polysialic acid and STX, a human polysialyltransferase, is correlated with tumor progression in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3072–3080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor G. Sialidases: structures, biological significance and therapeutic potential. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1996;6:830–837. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(96)80014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor PW. United States Patent 4695541 Enzymatic detection of bacterial capsular polysaccharide antigens. 1987

- Tomlinson S, Taylor PW. Neuraminidase associated with coliphage E that specifically depolymerises the Escherichia coli K1 capsular polysaccharide. J Virol. 1985;55:374–378. doi: 10.1128/jvi.55.2.374-378.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troy FA. Polysialylation: from bacteria to brains. Glycobiology. 1992;2:5–23. doi: 10.1093/glycob/2.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varki A, Higa H. Studies of the O-acetylation and (in) stability of polysialic acid. In: Roth J, Rutishauser U, Troy FA II, editors. Polysialic Acid: from Microbes to Man. Basel, Switzerland: Birkhäuser-Verlag; 1993. pp. 165–170. [Google Scholar]

- Vimr ER, Lawrisuk L, Galen J, Kaper JB. Cloning and expression of the Vibrio cholerae neuraminidase gene nanH in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1495–1504. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.4.1495-1504.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade RC. ‘Flu’ and structure-based drug design. Structure. 1997;5:1139–1145. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00265-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker JE, Saraste M, Runswick MJ, Gay NJ. Distantly related sequences in the alpha-subunits and beta-subunits of ATP synthase, myosin, kinases and other ATP-requiring enzymes and a common nucleotide binding fold. EMBO J. 1982;1:945–951. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal O, Jann K. Bacterial lipopolysaccharides: extraction with phenol-water and further applications of the procedure. In: Whistler R, BeMiller J, Wolfrom M, editors. Methods in Carbohydrate Chemistry. Vol. V. London, UK: Academic Press; 1965. pp. 83–91. [Google Scholar]