Uterine prolapse is the herniation of the uterus into or beyond the vagina as a result of failure of the ligamentous and fascial supports. It often coexists with prolapse of the vaginal walls, involving the bladder or rectum. In the United Kingdom, the disorder accounts for 20% of women waiting for major gynaecological surgery.1

Sources and selection criteria

We searched Medline (1966-2007), using the key words “uterine prolapse”, “surgical management”, “pessary”, and “conservative management”. We also reviewed the Cochrane database, as well as the BMJ archives, including BMJClinical Evidence.

Why should I read this article?

Most women with symptoms of prolapse will present to primary care, and initial assessment and treatment occurs here.2 An understanding of the pathophysiology, assessment, and management of prolapse is essential for the primary care team to streamline appropriate referrals to hospital. This article aims to cover these topics and to provide an overview of current management of secondary care.

Summary points

Uterine prolapse can occur at the same time as prolapse of the anterior or posterior vaginal compartments

Little is known about the prevalence and natural progression of prolapse

Initially, patients should be assessed and managed conservatively in primary care

Conservative management is advised for patients who are not fit for surgery or do not want surgery

Surgical treatment for uterine prolapse should incorporate procedures to prevent recurrence

Reliable evidence for both conservative and surgical treatment options is lacking, but randomised trials are under way

How common is uterine prolapse?

The exact prevalence is unknown. Forty per cent of participants in the women's health initiative (WHI) trial in the United States had some degree of prolapse. Uterine prolapse was found in 14% of the 27 342 women enrolled in the study.3 Another US study of 149 554 women found an 11% lifetime risk of surgery for prolapse or incontinence in the United States.4

The Oxford Family Planning Association study in the United Kingdom followed more than 17 000 women aged 25-39.5 The annual incidence of hospital admission with prolapse was 20.4/10 000, and the annual incidence of surgery for prolapse was 16.2/10 000. Many studies do not distinguish between prolapse of all pelvic organs and prolapse of the uterus alone, which makes it difficult to determine the true incidence.

Four hundred and twelve women originally enrolled in the WHI study were followed up to assess progression of prolapse. Spontaneous regression was common, especially for grade 1 prolapse—the progression rate was 1.9/100 women years and the regression rate was 48/100 women years.6 Thus, prolapse is not always progressive.

Why does prolapse occur?

Anatomy

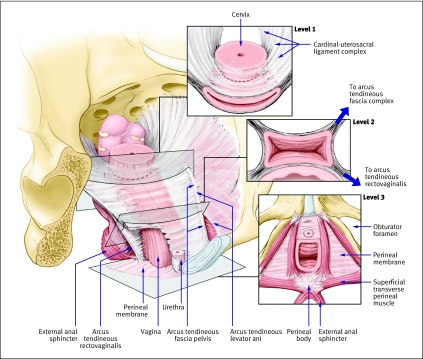

Some knowledge of normal vaginal support is needed to understand the pathophysiology of pelvic organ prolapse. Delancey's three levels of support (figure) are now accepted worldwide.7

Delancey's three levels of pelvic support. Reprinted from Barber,8 with permission from the Cleveland Clinic Foundation

Level 1: The cardinal-uterosacral ligament complex provides apical attachment of the uterus and vaginal vault to the bony sacrum. Uterine prolapse occurs when the cardinal-uterosacral ligament complex breaks or is attenuated.

Level 2: The arcus tendineous fascia pelvis and the fascia overlying the levator ani muscles provide support to the middle part of the vagina.

Level 3: The urogenital diaphragm and the perineal body provide support to the lower part of the vagina.

Risk factors

The aetiology of pelvic organ prolapse is multifactorial (box 1). The pelvic organ support study found age to be a risk factor for pelvic organ prolapse—risk doubled with each decade of life.9 Increasing parity was also associated with increasing severity of prolapse. Of the 17 000 women in the Oxford family planning study, those with a history of two vaginal deliveries were 8.4 times more likely to have surgery for prolapse than those with no such history.5

Box 1 Risk factors for the development of prolapse2 4 7 9 10

Confirmed risk factors

Older age

Race

Family history

Increased body mass index

Higher parity

Vaginal delivery

Constipation

Possible risk factors

Intrapartum variables (macrosomia, long second stage of labour, episiotomy, epidural analgesia)

Increased abdominal pressure

Menopause

Although vaginal delivery is clearly associated, specific obstetric risk factors remain controversial. Macrosomia, prolonged second stage of labour, episiotomy, anal sphincter injury, epidural analgesia, and the use of forceps and oxytocin have all been proposed as risk factors but have not been proved.

Women who are overweight (body mass index 25-30; odds ratio 2.51, 95% confidence interval 1.18 to 5.35) or obese (>30; 2.56, 1.23 to 5.35) are at high risk of developing prolapse.10 Heritable or genetic factors might play a part. In a case control study of 108 women with and without prolapse, a higher risk of prolapse was seen in women with a mother (3.2, 1.1 to 7.6) or sister (2.4, 1.0 to 5.6) reporting prolapse.11

Although menopause is often cited as a risk factor for pelvic organ prolapse, a study of 270 women from the WHI trial who had undergone hysterectomy found no association between oestrogen status (use of hormone replacement therapy) and prolapse.12

What are the symptoms?

Many symptoms have been attributed to prolapse (box 2), although none of them are specific, except for seeing or feeling a vaginal bulge. A study of 497 women in the US under annual review for prolapse10 showed that the number of symptoms and the problems these caused increased as the stage of prolapse increased from stage 0 (no prolapse) to stage III (prolapse outside the vagina) (box 3).

Box 2 Symptoms attributable to uterine prolapse

Vaginal symptoms

Sensation of a bulge or protrusion

Seeing or feeling a bulge

Pressure

Heaviness

Urinary symptoms

Incontinence, frequency, or urgency

Weak or prolonged urinary stream

Feeling of incomplete emptying

Manual reduction of prolapse needed to start or complete voiding (“digitation”)

Change of position needed to start or complete voiding

Bowel symptoms

Incontinence of flatus, or liquid or solid stool

Feeling of incomplete emptying

Straining during defecation

Digital evacuation needed to complete defecation

Splinting (pushing on or around the vagina or perineum) needed to start or complete defecation (“digitation”)

Sexual symptoms

Dyspareunia (painful or difficult intercourse)

Lack of sensation

Examining the patient

A pelvic examination should be done (using a Sim's single bladed speculum) to define the extent of the prolapse and establish the compartments of the vagina affected (anterior, posterior, or apical). The patient should be at rest and straining during a Valsalva manoeuvre. The oestrogen status of the tissues (signs of vaginal atrophy) and the size and mobility of the uterus and adnexae should be assessed.

Several prolapse grading systems exist, but the only system that has been robustly tested for both interobserver and intraobserver reliability is the pelvic organ prolapse quantification system.13 14 This system defines the extent of prolapse by measuring the descent of anterior, posterior, and apical segments of the vaginal wall relative to the vaginal hymen. A full discussion is beyond the scope of our review, but readers are referred to the original paper.14 The score for each compartment can be summarised into a staging system (box 3).

Box 3 The five stages of prolapse13 14

Stage 0: No prolapse

Stage I: The most distal portion of the prolapse is >1 cm above the level of the hymen

Stage II: The most distal portion of the prolapse is ≤1 cm proximal or distal to the hymen

Stage III: The most distal portion of the prolapse is >1 cm below the hymen but protrudes no further than 2 cm less than the total length of the vagina

Stage IV: Complete eversion of the vagina

The need for additional investigations beyond a comprehensive history and physical examination depends on the patient's presenting symptoms. Other tests that may be needed include urinalysis and urodynamic investigation.

Management

Observation

The extent of the prolapse does not correlate well with the symptoms. Watchful waiting is most appropriate if the prolapse is minimal (stage I). Some women may prefer observation for advanced prolapse—they should be examined periodically to look for development of new symptoms or disorders (such as obstructed urination or defecation, vaginal erosion).

Conservative treatment

Pelvic floor muscle training

Pelvic floor muscle training is an effective treatment for urinary incontinence, but its role in managing prolapse is unclear.15 A Cochrane review of conservative management of uterine prolapse published in 2006 concluded that there was no evidence from randomised trials and that further trials were needed.16 A feasibility study for the pelvic organ prolapse physiotherapy study—which will evaluate the effectiveness of pelvic floor muscle training in treating pelvic prolapse—has since been completed, and a fully powered randomised follow on trial in 16 global centres is due to start in 2007.17

Pessaries

Vaginal pessaries are the only currently available non-surgical intervention for managing women with prolapse (box 4).

Box 4 Key points for fitting pessaries and their subsequent management

Fitting

Ensure that the patient's bladder and bowel are empty

The pessary fits well if a finger can be swept between the pessary and the walls of the vagina

The goal is to fit the largest pessary that does not cause discomfort

Ask the patient to walk around, bend, and micturate to ensure that the pessary is retained

Management

No consensus exists on how frequently to see a patient after a pessary is fitted successfully

At each follow-up visit ask the patient about any new symptoms and inspect for erosions, ulcers, or discharge

Fitting a pessary can unmask symptoms of urinary incontinence

Although evidence to support the use of pessaries is not robust, they are used by 86% of gynaecologists and 98% of urogynaecologists.18 In a prospective study of 100 consecutive women with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse fitted with a pessary, 73 women retained the pessary two weeks later. After two months, 92% of these women were satisfied with the pessary; virtually all symptoms of prolapse and 50% of urinary symptoms had resolved, although occult stress incontinence was unmasked in 21% of the women.19

We found just one small prospective study that looked at whether pessaries can alter the natural history of prolapse. Fifty six women were prospectively evaluated using the pelvic organ prolapse quantification system. All women had a pessary fitted for at least one year. Of the 19 women who continued to use pessaries, the stage of the prolapse improved in four.20

In 2004, a Cochrane review found no randomised trials of pessary use in women with prolapse.21 A feasibility study for a randomised trial of the use of vaginal pessaries combined with pelvic floor exercises is due to start in 2007.22

Surgical treatment

In England and Wales in 2005-2006, 22 274 operations were performed for “vaginal prolapse.”23 The literature reports outcomes from surgery for uterine prolapse alone, and in conjunction with vaginal prolapse repairs at the same time. Many recent papers are confounded by heterogeneity of the patients studied, and a considerable proportion of patients had continence surgery with suburethral tape procedures at the same time. Hysterectomy for uterine prolapse can be performed via the abdominal route or vaginal route, although vaginal hysterectomy is preferred in the UK. In a study of all hysterectomies performed in the UK during 1993 and 1994, one third were done vaginally, and 95% of these were for prolapse.24

The greatest challenge in surgery for uterine prolapse is to prevent subsequent prolapse of either the vault or anterior or posterior walls of the vagina. Hysterectomy alone fails to correct the loss of integrity of the cardinal-uterosacral ligament complex and weakening of the pelvic diaphragm. A variety of procedures are available to support the vaginal vault at the time of hysterectomy. These include the vaginal procedures McCall culdoplasty; plication of the uterosacral ligament; sacrospinous or prespinous fixation for vaginal vault prolapse; and sacrocolpopexy (performed via an open procedure or laparoscopically). A retrospective case control study compared 62 women having sacrospinous fixation with 62 women having McCall culdoplasty at the time of vaginal hysterectomy. It found that women who had McCall culdoplasty had fewer recurrences (15% v 27%).25

We found only one published Cochrane review that looked at surgery for all types of prolapse. The meta-analysis of trials of vault suspension procedures showed that abdominal sacrocolpopexy was associated with a lower recurrence of vault prolapse and less dyspareunia than vaginal sacrospinous colpopexy. However, too few data on subjective success rate, patient satisfaction, and effect on quality of life were available to make reliable conclusions.26 In the past five years, several randomised and non-randomised studies have assessed the efficacy of various procedures with and without artificial meshes for preventing vault prolapse after hysterectomy. At present, however, even after meta-analysis the data have limited ability to inform decision making, particularly with respect to long term efficacy and the effect on sexual function. Large randomised trials to look at long term cure and complications after surgery for uterine prolapse are urgently needed.

Additional educational resources

Resources for health professionals

Conservative management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. www.cochrane.org/reviews/en/ab003882.html

Mechanical devices for pelvic organ prolapse in women. www.cochrane.org/reviews/en/ab004010.html

Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. www.cochrane.org/reviews/en/ab004014.html

BMJ Clinical Evidence. Genital prolapse in women. www.clinicalevidence.com/ceweb/conditions/woh/0817/0817.jsp

Resources for patients

NHS Direct (http://cks.library.nhs.uk/patient_information_leaflet/prolapse_of_the_uterus )—Information on causes, symptoms, and treatment of prolapse of the uterus

Prolapse of the Pelvic Organ (www.womenshealthlondon.org.uk/leaflets/prolapse/prolapse.html)—Detailed information on uterine prolapse

JAMA (http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/reprint/293/16/2054.pdf)—Patient page on uterine prolapse

What do we still need to know?

Many aspects of the cause, incidence, prevalence, and natural history of pelvic organ prolapse are unclear. No consensus or evidence exist about whether and how to treat women with prolapse. We do not know whether we should intervene in the absence of symptoms, despite anatomical changes. We also do not know the optimal timing for intervention, or whether early intervention reduces the incidence of recurrence.

We do not know whether conservative management can prevent or delay the need for surgery, and the best surgical approach to achieve anatomical cure, resolution of symptoms, and low rates of recurrence in not known. Large prospective randomised studies with long term follow-up are needed to answer all these questions.

Contributors: AD searched the literature, obtained the primary papers, and drafted the paper. RECT and CJM reviewed and revised the draft manuscript and approved the final version. DGT discussed the search strategy, reviewed the papers, contributed to and revised the draft manuscript, and approved the final version. DGT is guarantor.

Competing interests: DGT currently sits on the advisory board of clinical studies funded by Eli Lilly and Company and Johnson and Johnson Medical. Consultancy payments for these studies are managed by the University of Leicester research and business office and are used to support his research. DGT is also principal investigator on three investigator initiated studies funded by grants from Johnson and Johnson, Astellas Pharma, and UCB Pharma. In 2006, he received grants towards attending international scientific meetings from American Medical Systems, Astellas, Pfizer, UCB Pharma, and Janssen Cilag. CJM has provided surgical training in the use of the TVT and TVT-O devices, and the Apogee and Perigee mesh systems for prolapse surgery during sessions organised by Johnson and Johnson and American Medical Systems. He has received honorariums for speaking at international meetings.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Cardozo L. Prolapse. In: Whitfield CR, ed. Dewhurst's textbook of obstetrics and gynaecology for postgraduates Oxford: Blackwell Science, 1995:642-52.

- 2.Department of Health. 18 week commissioning pathway. Pelvic organ prolapse. Version 4. www.18weeks.nhs.uk/cms/ArticleFiles/kshr3sbwp2mustvmrgxfba5515022007092842/Files/18wkPathway_Prolapse_Women_060807.pdf

- 3.Hendrix SL, Clark A, Nygaard I, Aragaki A, Barnabei V, McTiernan A. Pelvic organ prolapse in the women's health initiative: gravity and gravidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;186:1160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 1997;89:501-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mant J, Painter R, Vessey M. Epidemiology of genital prolapse: observations from the Oxford family planning association study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1997;104:579-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Handa VL, Garrett E, Hendrix S, Gold E, Robbins J. Progression and remission of pelvic organ prolapse: a longitudinal study of menopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;190:27-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeLancey JO. Anatomic aspects of vaginal eversion after hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992;166:1717-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barber MD. Contemporary views on female pelvic anatomy. Cleve Clin J Med 2005;72(suppl 4):S3-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swift SE, Woodman P, O'Boyle A, Kahn M, Valley M, Bland D, et al. Pelvic organ support study (POSST): the distribution, clinical definition and epidemiology of pelvic organ support defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;192:795-806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swift SE, Tate SB, Nicholas J. Correlation of symptoms with degree of pelvic organ support in a general population of women: what is pelvic organ prolapse? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;189:372-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiaffarino F, Chatenoud L, Dindelli M, Meschia M, Buonoguidi A, Amicarelli F, et al. Reproductive factors, family history, occupation and risk of urogential prolapse. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1999;82:63-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nygaard I, Bradley C, Brandt D. Pelvic organ prolapse in older women: prevalence and risk factors. Obstet Gynecol 2004;104:489-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barber MD, Walters MD, Bump RC. Association of the magnitude of pelvic organ prolapse and presence and severity of symptoms. The American Urogynecologic Society 24th Annual Scientific Meeting, 2003. Paper presentations, paper 19. .www.augs.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=268

- 14.Hall AF, Theofrastous JP, Cundiff GW, Harris RL, Hamilton LF, Swift SE, et al. Interobserver and intraobserver reliability of the proposed International Continence Society, Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, and American Urogynecologic Society pelvic organ prolapse classification system. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996;175:1467-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poma PA. Non surgical management of genital prolapse—a review and recommendation for clinical practice. J Reprod Med 2000;45:789-97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hagen S, Stark D, Maher C, Adams E. Conservative management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(4):CD003882. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.University of Aberdeen. Pelvic organ prolapse physiotherapy. 2007. www.abdn.ac.uk/hsru/hta/poppy.shtml

- 18.Cundiff GW, Weidner AC, Visco AG, Bump RC, Addison WA. A survey of pessary use by members of the American Urogynaecologic Society. Obstet Gynecol 2000;95:931-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clemons JL, Aguilar VC, Tillinghast TA, Jackson ND, Myers DL. Patient satisfaction and changes in prolapse and urinary symptoms in women who were fitted successfully with a pessary for pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;190:1025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Handa VL, Jones M. Do pessaries prevent progression of pelvic organ prolapse? Int J Urogynecol 2002;13:349-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adams E, Thomson A, Maher C, Hagen S. Mechanical devices for pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(2):CD004010. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Wellbeing of Women. Vaginal rings and pelvic floor exercises for pelvic organ prolapse—are they better used together? 2007. .www.wellbeingofwomen.org.uk/index.asp?PageID=373

- 23.Hospital Episode Statistics. 2005. . www.hesonline.nhs.uk/Ease/servlet/ContentServer?siteID=1937&categoryID=204

- 24.Maresh MJA, Metcalfe MA, McPherson K, Overton C, Hall V, Hargreaves J, et al. The VALUE national hysterectomy study: description of the patients and their surgery. BJOG 2002;109:302-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colombo M, Milani R. Sacrospinous ligament fixation and modified McCall culdoplasty during vaginal hysterectomy for advanced uterovaginal prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1998;179:13-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maher C, Baessler K, Glazener CMA, Adams EJ, Hagen S. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(4):CD004014. [DOI] [PubMed]