Abstract

Neuronal nitric-oxide synthase (nNOS) is subject to alternative splicing. In mice with targeted deletions of exon 2 (nNOSΔ/Δ), two alternatively spliced forms, nNOSβ and γ, which lack exon 2, have been described. We have compared localizations of native nNOSα and nNOSβ and γ by in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry in wild-type and nNOSΔ/Δ mice. To assess nNOS catalytic activity in intact animals we localized citrulline, which is formed stoichiometrically with NO, by immunohistochemistry. nNOSβ is prominent in several brain regions of wild-type animals and shows 2-to 3-fold up-regulation in the cortex and striatum of nNOSΔ/Δ animals. The persistence of much nNOS mRNA and protein, and distinct citrulline immunoreactivity (cit-IR) in the ventral cochlear nuclei and some cit-IR in the striatum and lateral tegmental nuclei, indicate that nNOSβ is a major functional form of the enzyme in these regions. Thus, nNOSβ, and possibly other uncharacterized splice forms, appear to be important physiological sources of NO in discrete brain regions and may account for the relatively modest level of impairment in nNOSΔ/Δ animals.

Keywords: ornithine transcarbamoylase, postsynaptic density protein 95, citrulline

Nitric oxide (NO), formed by neuronal nitric-oxide synthase (nNOS) (1), has major signaling functions in the central and peripheral nervous system (2, 3). Alternative splicing of the nNOS gene is prominent with more than 10 differently spliced nNOS transcripts reported (4–10). The principal, exon 2-containing, form of nNOS (nNOSα) accounts for the great majority of catalytic activity in the brain, as mice with targeted deletions of exon 2 (nNOSΔ/Δ) display an ≈95% reduction in NOS catalytic activity (11). Though NO has been implicated in development (12) and synaptic plasticity (13), these mice appear grossly normal, lack obvious histopathological abnormalities in the central nervous system, and reproduce effectively (11), suggesting that the residual NOS activity might protect the nNOSΔ/Δ mutant mice from serious pathology. Two alternatively spliced forms of nNOS, β and γ, that lack exon 2 and thus persist in the nNOSΔ/Δ mice, have a regional distribution that parallels the pattern of the residual activity (4).

The human nNOS gene contains 29 exons of which all but exon 1 are translated to generate nNOSα, a 150-kDa protein (1, 8). nNOSβ and γ, as described in mice, are generated by alternative splicing that skips exon 2 and employs different first exons, 1a and 1b, respectively (4) (Fig. 1). Translation of nNOSβ is initiated at a CTG-initiation codon within exon 1a generating a 136-kDa NOS protein with six unique N-terminal amino acids. Translation of nNOSγ is initiated at an ATG-initiation codon within exon 5 generating a truncated, 125-kDa form of nNOSα. Both nNOSβ and nNOSγ lack the PSD-95/discs large/ZO-1 homology domain (PDZ) domain that is localized within exon 2. This domain, also referred to as DHR or GLGF, mediates association of nNOSα with postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD-95; ref. 4). PSD-95 appears to anchor nNOSα to neuronal membranes in the vicinity of the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor (17, 18), thus coupling NOS activation to calcium influx via the NMDA receptor. Because nNOSβ and γ lack the PDZ domain, they are localized to the cytosolic fraction (4) and might not be anticipated to respond to NMDA receptor stimulation, leaving their ability to be activated in vivo unclear. In vitro assays of the isoforms indicate that nNOSγ lacks significant catalytic activity, whereas nNOSβ possesses activity comparable to nNOSα (4). Thus, nNOSβ might be the source of the residual activity in nNOSΔ/Δ.

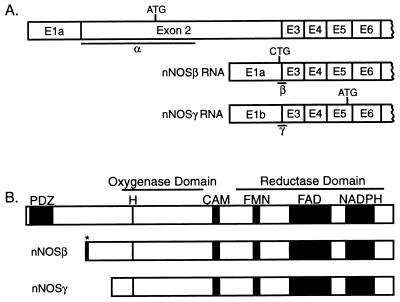

Figure 1.

Isoforms of neuronal NOS. (A) Illustration of mRNAs generated by alternative splicing of the nNOS gene. (Top) The predominant form in wt. Location of start codons and regions recognized by the nNOS α, β, and γ in situ probes are indicated. (Adapted from refs. 4 and 8.) (B) Illustration of nNOS isoforms. Consensus binding sites for heme (H), calmodulin (CAM), flavin mononucleotide (FMN), flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), and the reduced form of NADPH are indicated. nNOSβγ both lack the PDZ domain (PDZ), but the primary structure of the catalytic domains appears intact. ∗, six amino acids unique to nNOSβ. Based on refs. 14–16.

To assess the functional importance of nNOS isoforms in the brain, we have localized nNOSα, β, and γ by in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry, and evaluated in vivo catalytic activity by staining for citrulline, which is formed by NOS stoichiometrically with NO (19). Substantial nNOSβ in discrete areas with citrulline staining that persists in nNOSΔ/Δ indicate prominent roles for this NOS subtype.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Material.

C57B6 mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory and housed at the Johns Hopkins Animal Care Facility. A polyclonal antiserum to the C-terminal region of human nNOS (residues 1419–1433) was kindly provided by Jeffrey Spangenberg (Incstar, Stillwater, MN) and used at a 1:15,000 dilution. Glutaraldehyde was from EM Science. Gold chloride was from Aldrich. Alkaline phosphatase-coupled anti-rabbit antiserum was from The Jackson Laboratory. The peroxidase Elite staining kit and VIP kit were from Vector Laboratories. All other reagents were from Sigma.

Preparation of Polyclonal Antiserum to Citrulline.

The protocol used was similar to the one previously used to generate antibodies specific for d-serine (20). Citrulline was coupled to BSA with glutaraldehyde and then reduced with NaBH4 (21). After extensive dialysis against water, the conjugate was adsorbed to freshly prepared 45-nm colloidal gold particles (22). A rabbit was immunized intradermally every 3 weeks with the BSA conjugate alone and i.v. with the gold particles. Before use, all citrulline used in this study was incubated for 2 hr at room temperature with Sepharose beads coupled to glutaraldehyde-treated BSA, to eliminate antibodies not selective for citrulline (23). Liquid-phase conjugates of various amino acids to glutaraldehyde were prepared identically to the original immunogen, except that BSA was omitted and free aldehyde groups were blocked with excess Tris. For dot-blot screens, various amino acids were coupled to dialyzed rat brain cytosol with glutaraldehyde as described above for citrulline/BSA conjugates, and then spotted on nitrocellulose. After overnight incubation with the primary antiserum, blots were visualized with an alkaline phosphatase-coupled anti-rabbit secondary antiserum. High-affinity antibodies appeared after 7 months of immunization.

Immunohistochemistry.

Anesthetized mice (age >50 days) were perfused through the left ventricle for 30 sec with 37°C oxygenated Krebs–Henseleit buffer and then at 15 ml/min with 250 ml of 37°C 5% glutaraldehyde/0.5% paraformaldehyde containing 0.2% Na2S2O5 in 0.1 M sodium phosphate (pH 7.4). Brains were postfixed in the same buffer for 2 hr at room temperature. After cryoprotection for 2 days at 4°C in 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.4/0.1 M NaCl/20% (vol/vol) glycerol, brain sections (20–40 μm) were cut on a sliding microtome. Free-floating brain sections were reduced for 20 min with 0.5% NaBH4 and 0.2% Na2S2O5 in PBS (10 mM, pH 7.4/0.19 M NaCl), washed for 45 min at room temperature in PBS containing 0.2% Na2S2O5, blocked with 4% normal goat serum for 1 hr in the presence of 0.2% Triton X-100, and incubated overnight at 4°C with the citrulline antiserum diluted 1:10,000 to 1:5,000 in PBS containing 2% goat serum and 0.1% Triton X-100. Immunoreactivity was visualized with the Vectastain ABC Elite kit (Vector Laboratories). To test immunohistochemical specificity, liquid-phase conjugates of glutaraldehyde and citrulline (0.2 mM amino acid) were incubated for 4 hr with antiserum (1:5,000) before incubation with brain sections. Immunohistochemistry was routinely done in the presence of liquid-phase glutaraldehyde conjugates of l-arginine, and l-glutamate to minimize any cross-reactivity to amino acids with similar structure to citrulline that occur in high concentrations in brain. For double labeling, brain sections were sequentially stained with nNOS and citrulline antisera. After completing staining with the first antiserum (citrulline), sections were microwaved as described (24). The first primary was visualized with the Vectastain ABC Elite Kit. The second primary was visualized with the Vector VIP substrate kit for peroxidase. Microwaved sections for which the second primary were excluded exhibited no additional staining.

In Situ Hybridization.

Probes for digoxygenin in situ hybridization corresponding to the C terminus of nNOS were generated from the SalI-EcoRI fragment of rat nNOS corresponding to residues 4196–5057. Exon 2-specific probes were generated by amplifying a 687-bp fragment via PCR beginning at the ATG initiator methionine of nNOSα and corresponding to residues 100–786 of the published mouse nNOS sequence. Both sequences were subcloned into pBluescript, and sense and antisense cRNA probes were generated by T3 and T7 RNA polymerases. In situ hybridization was carried out as described (25). Sections hybridized with identical amounts of sense cRNA in both cases yielded no specific signal.

Radioactive in Situ Hybridization.

Oligos for radioactive in situ hybridization to specific nNOS splice forms were generated as follows: TGTGCAGTTTGCCGTCGAGGTCTCTGCTGCCGAGCCCGCGCAGTTCC, corresponding to the junction of exons 1a and 3 and specific to nNOSβ; TGTGCAGTTTGCCGTCGAGGTCTCTGGAAGGCAAGGTGGCTGGGGC, corresponding to the junction of exons 1b and 3 and corresponding to nNOSγ; and TCAGGTGCAGGGTGTCAGTGAGGACCACATCTGTCTCCCAGTTCTTCACC, corresponding to residues 1004–1053 of exon 3, and complementary to all published splice forms of nNOS.

In addition, the following control probes were generated: probe 3, TGTGCAGTTTGCCGTCGAGGTCTCTG(N)25; probe 1a, (N)25 CTGCCGAGCCCGCGCAGTTCC; probe 1b, (N)25 GAAGGCAAGGTGGCTGGGGC; and GGTCAAGAACTGGGAGACAGATGTGGTCCTCACTGACACCCTGCACCTGA, corresponding to the sense strand of the exon 3 oligo.

Probes 1a and 3, and 1b and 3 were labeled, combined, and used together, at 1 million cpm per slide each, as controls for specific hybridization of nNOSβ and nNOSγ-specific probes. The exon 3 sense probe was labeled and used at 2 million cpm per slide as a control for general nonspecific hybridization. None of these showed appreciable signal.

Hybridization was carried out essentially as described (26). Forty nanograms of each probe was terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase end-labeled with 33P, and each were used at 2 million cpm per slide. Sections were hybridized overnight at 45°C, and then washed at 72°C in 0.6 × SSC, 4 × 30 min. After drying and overnight exposure to Hyperfilm (Amersham), sections were dipped in NBT-2 emulsion (Kodak), developed 12 days at 4°C, and counterstained with cresyl violet.

RESULTS

Visualization of NOS Activity via Antibodies to Citrulline.

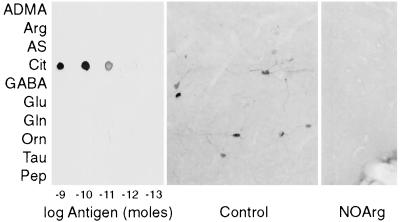

To provide microscopic visualization of NOS catalytic activity, we developed an antiserum to citrulline. The antiserum was raised in rabbits against a glutaraldehyde conjugate of citrulline and BSA. To evaluate sensitivity and specificity, we coupled various amino acids and a peptide to dialyzed rat brain cytosol with glutaraldehyde and spotted the preparations onto nitrocellulose. Dot blots were probed with a 1:10,000 dilution of the citrulline antibodies (Fig. 2 Left). The antiserum gave a robust signal for 10 pmol of citrulline and a faint one for 1 pmol. One nanomole of the other constructs tested exhibited no cross-reactivity. The antiserum was, therefore, at least 1,000-fold less sensitive to compounds structurally similar to citrulline (ADMA, arginine, argininosuccinate, and ornithine); amino acids found in great abundance in the brain (γ-aminobutyrate, glutamate, glutamine, and taurine); a 20-residue peptide containing arginine, glutamine, and glutamate residues; and cytosolic brain protein. Staining of tissue sections with 1:5,000 dilution of the antiserum was completely blocked by preabsorption overnight with 200 μM of the immunizing antigen (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Citrulline antiserum specificity. (Left) Dialyzed rat brain cytosol was coupled to various ligands with glutaraldehyde and then reduced with NaBH4. Serial 1:10 dilutions of each conjugate were spotted onto three pieces of nitrocellulose and then probed with a 1:10,000 dilution of antiserum. ADMA, asymmetric NG,NG-dimethylarginine; Arg, arginine; AS, argininosuccinate; Cit, citrulline; GABA, γ-aminobutyrate; Glu, glutamate; Gln, glutamine; Orn, ornithine; Tau, taurine; Pep, human glycine decarboxylase (residues 1,000–1,020). (Center) Mouse basal forebrain/islands of Calleja stained with 1:10,000 dilution of antiserum. Neuronal soma and processes are clearly labeled. (Right) Same area in mouse treated with nitroarginine, 50 mg/kg i.p. twice a day for 4 days. No neuronal staining is evident in this or other areas (data not shown) of the brain.

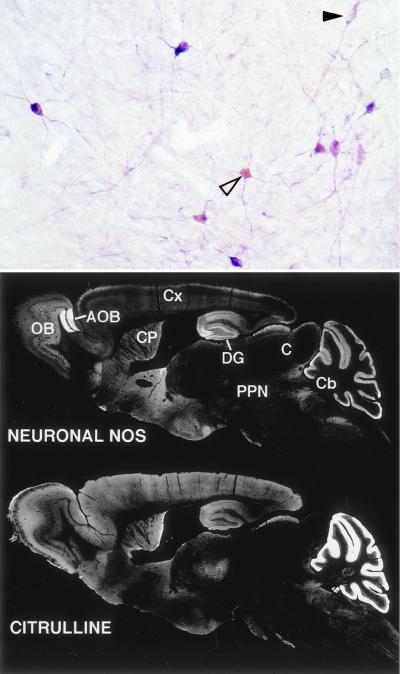

To use citrulline immunoreactivity (cit-IR) as a monitor of NOS activity one must establish that citrulline is only synthesized by NOS in the brain. Ornithine transcarbamoylase (OTC) synthesizes large amounts of citrulline as a component of the urea cycle. However, both OTC and carbamoylphosphate synthetase 1 are considered to be absent from the brain (27, 28). Indeed, while Northern blots for OTC give a strong signal in rat liver, we fail to detect any signal in rat brain (results not shown). Furthermore, chronic treatment with nitroarginine, an apparent irreversible NOS inhibitor (29), abolishes neuronal cit-IR (Fig. 2 Right). Finally, in double-labeling experiments all citrulline-positive neurons observed were also NOS positive. However, many NOS-positive neurons were not citrulline positive, implying lack of catalytic activity (Fig. 3). Our findings are in agreement with a previous study by Vincent and associates (30). Using a different citrulline antiserum and NADPH-diaphorase staining, a histochemical marker for NOS, they showed that all cit-IR cells were also NADPH-diaphorase positive (30).

Figure 3.

Comparison of cit-IR and nNOS-IR. (Top) Double labeling for nNOS (purple) and citrulline (light brown-yellow). All cit-IR cells observed were also nNOS-IR, although many nNOS-IR cells devoid of cit-IR were observed (solid arrowhead). Cit-IR was especially high in the soma (open arrowhead), while nNOS-IR appeared both in the soma and processes. (Bottom) nNOS-IR and cit-IR in sagital sections of adult mouse. White areas represent positive staining. OB, olfactory bulb; AOB, accessory olfactory bulb; CP, caudate-putamen; DG, dentate gyrus; Cx, cerebral cortex; C, colliculi; PPN, pedunculopontine nuclei; Cb, cerebellum.

Citrulline Immunoreactivity Colocalizes with nNOS.

All intense citrulline staining was restricted to neurons with a very low level of staining in adjacent nonneuronal tissue. The general distribution of citrulline staining paralleled nNOS in wild-type (wt) mouse brain with dense staining in the olfactory bulb, superior colliculus, the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, the caudate-putamen, and the molecular and granular layers of the cerebellum (Fig. 3 Bottom). This is in agreement with previously reported localizations of nNOS and citrulline (31–33, 34). Thus, citrulline staining in the central nervous system is a measurement of NOS catalytic activity that varies among NOS-positive cells with some manifesting undetectable activity.

nNOS and Citrulline Immunoreactivity Persist in nNOSΔ/Δ Brain.

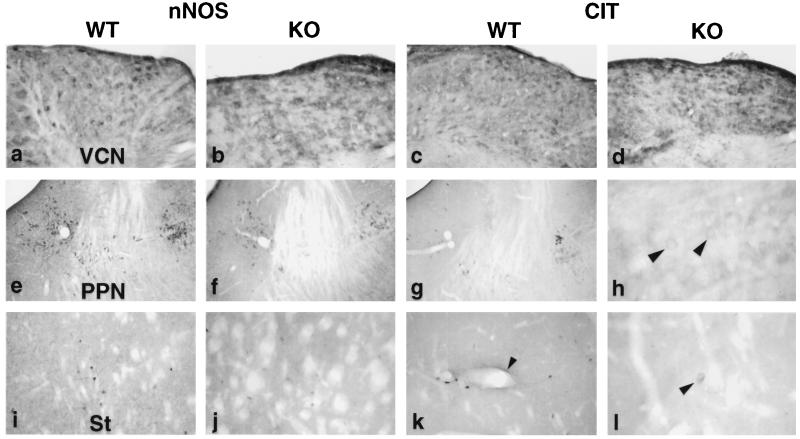

We observed considerable nNOS immunoreactivity (nNOS-IR) in nNOSΔ/Δ in many regions including striatum, cerebral cortex, basal forebrain, and brain stem. nNOS-IR appeared restricted to neurons and was confined to the cell soma and the most proximal processes (Fig. 4F and J). In stark contrast, nNOS-IR in wt brains was prominently localized to the processes (Fig. 4 E and I). These observations are consistent with nNOSβγ lacking the PDZ domain needed for membrane association. In the striatum and the cerebral cortex the numbers of cell soma IR for nNOS in nNOSΔ/Δ were somewhat (≈50%) reduced compared with wt, although the staining intensity was greatly reduced. In the brain stem of nNOSΔ/Δ, many nuclei stained significantly for nNOS. The pedunculopontine and laterodorsal tegmental nuclei (PPN/LDT) exhibited especially high IR, although the intensity is decreased compared with wt, and the prominent IR processes observed in the wt were absent in nNOSΔ/Δ (Fig. 4F). Independently, Brenman et al. (35) have reported a similar pattern of immunoreactivity in nNOSΔ/Δ. Failure of previous studies to detect immunoreactive nNOS protein in nNOSΔ/Δ probably reflects the use of lower affinity antisera and a less sensitive colorimetric detection system (11).

Figure 4.

Comparison of cit-IR and nNOS-IR in wild-type (WT) and nNOSΔ/Δ (KO) brains. VCN, ventral cochlear nucleus; PPN, pedunculopontine and laterodorsal tegmental nuclei; St, striatum. (h and l) High magnifications of the laterodorsal tegmental nucleus and striatum, respectively. Arrowheads (h and l) indicate cit-IR soma in nNOSΔ/Δ. Arrowhead (k) indicates one long, continuous cit-IR process. Dark areas indicate positive staining.

To examine catalytic activity of nNOSβγ in vivo, we localized citrulline. Cit-IR persisted in the ventral cochlear nucleus of nNOSΔ/Δ, implying that nNOSβ or γ was active in vivo (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, in the ventral cochlear nucleus nNOS-IR and cit-IR were not reduced in nNOSΔ/Δ, suggesting a prominent function for nNOSβγ in this nucleus (Fig. 4 A–D). In the wt striatum 10–20% of nNOS-IR cells were cit-IR. The cit-IR was greatly diminished in nNOSΔ/Δ striatum (Fig. 4L). Similarly, in the PPN/LDT, where 10–20% of nNOS-IR cells were also cit-IR in the wt, cit-IR was also greatly reduced with only a few weakly IR cell soma observed in the LDT (Fig. 4H). In nNOSΔ/Δ, cit-IR cells were scattered throughout the brain stem but were absent in the cerebral cortex (data not shown). Since nNOS-IR was only moderately reduced in nNOSΔ/Δ striatum and PPN/LDT, the loss of cit-IR implies that the residual nNOSβγ was less catalytically active than nNOSα.

Nonradioactive in Situ Hybridization Shows Substantial nNOS mRNA Expression in nNOSΔ/Δ Brain.

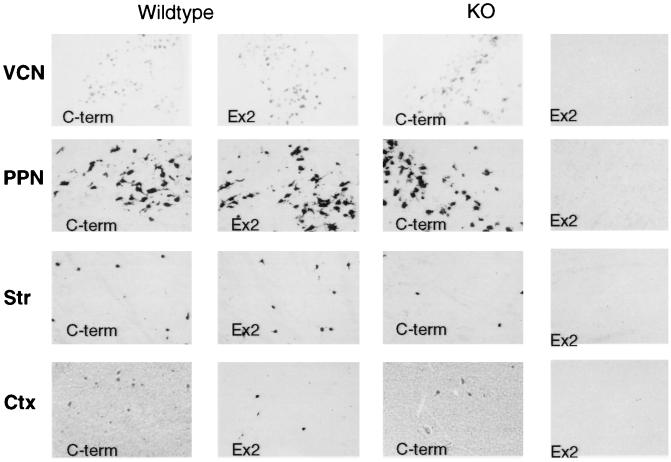

Nonradioactive in situ hybridization for the C-terminal domain of nNOS that occurs in nNOSα, β, and γ revealed mRNA levels in nNOSΔ/Δ, approximating wt levels in several regions such as PPN/LDT (Fig. 5) as well as the dorsal and ventral cochlear nuclei. In other regions, notably the cerebellum and olfactory granule cells (data not shown), no nNOS mRNA was detected in nNOSΔ/Δ. Likewise, nNOS mRNA was absent from the hypothalamus, with the exception of a few nuclei, and was expressed in >95% fewer cells in the dorsal and medial amygdala of nNOSΔ/Δ animals (data not shown). In the striatum and cerebral cortex, the number of cells expressing nNOS mRNA was roughly 50% of wt (Table 1). For cortical and striatal cells that do stain in nNOSΔ/Δ, however, the relative intensity of staining was the same as in wt.

Figure 5.

Comparison of mRNA localizations for nNOSa and total nNOS. cRNA digoxygenin in situ hybridization employed probes directed against nNOS C-terminal (C-term), representing total nNOS mRNA, and an nNOSα-specific probe (ex2) in wt and nNOSΔ/Δ (KO) animals. VCN, ventral cochlear nucleus; PPN, pedunculopontine nuclei; Str, striatum; Ctx, cerebral cortex. (×100.)

Table 1.

nNOS-positive cells in knockout and wild type

| Region | nNOS-positive cells per section

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Wild type | nNOSΔ/Δ | |

| Cortex | 51 ± 6.6 | 28 ± 5.4 |

| Striatum | 115 ± 14 | 70 ± 15 |

Data are means ± S.E.M. of 16–25 samples.

In the wt, the nNOSα mRNA localization pattern was closely similar to total nNOS mRNA in all brain regions examined (Fig. 5). The abolition of staining for nNOSα in knockout animals demonstrated the specificity of the in situ method.

Radioactive in Situ Hybridization Shows Substantial nNOSβ mRNA in Both Wt and nNOSΔ/Δ Brain.

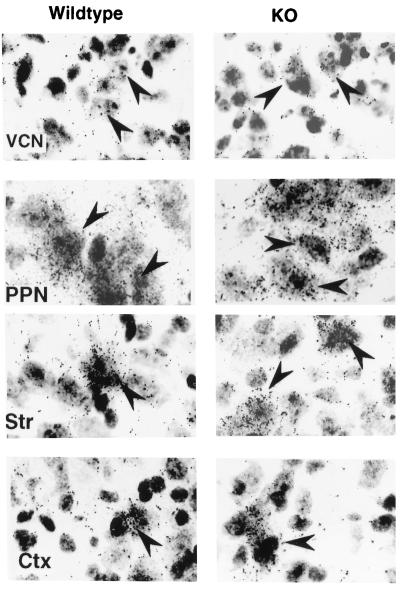

Probes designed to specifically recognize the nNOSβ, and γ isoforms of nNOS showed nNOSβ to be the predominant form in nNOSΔ/Δ. nNOSβ was also expressed in wt animals. nNOSβ levels were high in the PPN/LDT and similar in wt and nNOSΔ/Δ (Fig. 6). nNOSβ mRNA levels in the cochlear nucleus were low in both wt and nNOSΔ/Δ, but moderately increased in nNOSΔ/Δ. In wt striatum, nNOSβ occurred in roughly 5% of all nNOS-positive cells. By contrast, in nNOSΔ/Δ nNOSβ was present in 35–50% of all nNOS-positive cells, indicating up-regulation of expression. In the wt cerebral cortex, nNOSβ was present in 10% of all nNOS-positive cells in wt, and in 25–30% in nNOSΔ/Δ, reflecting some up-regulation of nNOSβ in nNOSΔ/Δ. nNOSγ-specific probes did not show appreciable levels of signal in any regions of either the nNOSΔ/Δ or the wt brain.

Figure 6.

nNOSβ mRNA localizations in wild-type and nNOSΔ/Δ (KO) mice. Radioactive oligonucleotide in situ hybridization employed the nNOSβ-specific probe. Arrowheads indicate selected cells showing black radioactive emulsion grains. Sections are counterstained with cresyl violet. Abbreviations are as in Fig. 5 legend. (×400.)

All regions expressing nNOSβ also expressed nNOSα, suggesting that the two isoforms are generally coexpressed in the same cells. In wt striatum, however, some cells may only express nNOSβ. Thus, hybridization of consecutive sections with probes directed against exon 2, reflecting nNOSα expression, and the C terminus of nNOS, reflecting expression of all nNOS splice forms, reveals that the number of nNOSα cells is only 88.1 ± 5.9% (n = 14) of all nNOS cells. Double-labeling experiments, however, are needed to conclusively answer this question.

DISCUSSION

nNOSα has been thought to account for 95% or more of all NOS catalytic activity in the brain, because of the low residual activity remaining in whole brain extracts of nNOSΔ/Δ (11). Our study revealed that nNOSβ is prominent in many brain areas and in wt mice can account for the major portion of citrulline formation in areas such as the cochlear nucleus. While large numbers of alternatively spliced forms of nNOS transcripts have been described, their relevance in vivo has been questioned. Our findings indicate that nNOSβ is catalytically active in vivo. We did not detect nNOSγ mRNA, suggesting that nNOSβ is the only functional alternative form of nNOS, though we may have failed to detect low levels of nNOSγ mRNA. Bredt and associates (4) reported that nNOSβ possesses activity comparable to nNOSα, whereas nNOSγ lacks activity. Thus, in brain regions with substantial citrulline staining in nNOSΔ/Δ and detectable nNOSβγ IR, nNOSβ probably accounts for the catalytic activity.

Previous studies indicate that a major portion of nNOS is associated with membranes (36). Membrane association of nNOS in neurons appears to be mediated by the PDZ domain and interactions with proteins such as PSD-95 and 93 (4). Since nNOSβ and γ lack the PDZ domain, they are cytosolic (4). Our evidence that nNOSβ is catalytically active in vivo indicates that membrane association is not required for catalytic activity. Activation of nNOS by stimulation of NMDA receptors is thought to depend on the localization of nNOS to the vicinity of the NMDA receptor via PSD-95 (4). We do not know whether nNOSβ can be activated by NMDA receptor stimulation.

Despite the importance of nNOS in many neuronal functions, nNOSΔ/Δ animals appear grossly normal. Could residual nNOSβ or other uncharacterized splice forms protect these mice from more extensive neuronal pathology? Substantial levels of nNOS occur in numerous brain regions of knockout animals. The only areas essentially devoid of nNOS mRNA in the knockout are the cerebellum, the main (but not the accessory) olfactory bulb, and the hypothalamus. The lack of nNOS mRNA in virtually all nuclei of the hypothalamus, and the >95% reduction in the number of cells in the dorsomedial nucleus of the amygdala containing nNOS mRNA, regions known to mediate male-specific aggression and sexual behavior (37), may account for the dramatic behavioral changes observed in nNOSΔ/Δ (38).

Excess production of NO is thought to mediate neuronal damage following vascular stroke (39). NOS inhibitors provide 60–70% protection against stroke damage (40, 41), while only a 38% protection occurs in nNOSΔ/Δ (42). Perhaps the absence of greater protection in the nNOSΔ/Δ animals stems from the persistence of nNOSβ in the cortex and striatum.

The pronounced up-regulation of nNOSβ in the striatum and cortex of nNOSΔ/Δ is not evident in other brain regions. This up-regulation might result from unique dynamic features of corticostriate neuronal circuitry. The amount of nNOSβ expression in nNOSΔ/Δ is not sufficient to fully account for all the remaining nNOS expression detected with the C-terminal probe. Brenman et al. (4) observed augmented Western blot staining for nNOSβγ protein in several brain regions of nNOSΔ/Δ animals. Since they employed an antiserum specific for the C-terminal region of nNOS, they may have detected novel alternatively spliced forms of the enzyme. These forms might encode proteins of the same length as nNOSβ and γ but with alternative untranslated first exons, and therefore would be undetectable with our oligonucleotide probes.

Acknowledgments

We thank David S. Bredt and Samie R. Jaffrey for helpful discussions, and Ted M. Dawson for help with breeding nNOSΔ/Δ. We thank Incstar for development of antibodies to nNOS under an agreement whereby Incstar may purchase antibodies from The Johns Hopkins Univerity. This work was supported by Public Health Service Grant DA-00266, Research Scientist Award DA-00074 to S.H.S., and a Gustavus and Louise Pfeiffer stipend to M.J.L.E.

ABBREVIATIONS

- cit-IR

citrulline immunoreactivity

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- nNOS

neuronal nitric oxide synthase

- NMDA

N-methyl-d-aspartate

- OTC

ornithine transcarbamoylase

- PSD-95

postsynaptic density protein 95

- PDZ

PSD-95/discs large/ZO-1 homology domain

- wt

wild type

References

- 1.Bredt D S, Snyder S H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:682–685. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.2.682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmidt H H H W, Walter U. Cell. 1994;78:919–925. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90267-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garthwaite J, Boulton C L. Annu Rev Physiol. 1995;57:683–706. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.003343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenman J E, Chao D S, Gee S H, McGee A W, Craven S E, Santillano D R, Wu Z, Huang F, Xia H, Peters M F, Froehner S C, Bredt D S. Cell. 1996;84:757–767. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silvagno F, Xia H, Bredt D S. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:11204–11208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.19.11204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Regulski M, Tully T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9072–9076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujisawa H, Ogura T, Kurashima Y, Yokoyama T, Yamashita J, Esumi H. J Neurochem. 1994;63:140–145. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63010140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall A V, Antoniou H, Wang Y, Cheung A H, Arbus A M, Olson S L, Lu W C, Kau C L, Marsden P A. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:33082–33090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogilvie P, Schilling K, Billingsley M L, Schmidt H H. FASEB J. 1995;9:799–806. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.9.7541381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xie J, Roddy P, Rife T K, Murad F, Young A P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1242–1246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.4.1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang P L, Dawson T M, Bredt D S, Snyder S H, Fishman M C. Cell. 1993;75:1273–1286. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90615-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bredt D S, Snyder S H. Neuron. 1994;13:301–313. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90348-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Son H, Hawkins R D, Martin K, Kiebler M, Huang P L, Fishman M C, Kandel E R. Cell. 1996;87:1015–1023. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81796-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richards M K, Marletta M A. Biochemistry. 1994;33:14723–14732. doi: 10.1021/bi00253a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doyle D A, Lee A, Lewis J, Kim E, Sheng M, MacKinnon R. Cell. 1996;85:1067–1076. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81307-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sessa W C, Harrison J K, Barber C M, Zeng D, Durieux M E, D’Angelo D D, Lynch K R, Peach M J. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15274–15276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aoki C, Fenstemaker S, Lubin M, Go C G. Brain Res. 1993;620:97–113. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90275-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kornau H C, Schenker L T, Kennedy M B, Seeburg P H. Science. 1995;269:1737–1740. doi: 10.1126/science.7569905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garthwaite J, Garthwaite G, Palmer R M J, Chess-Williams R. Nature (London) 1988;366:385–388. doi: 10.1038/336385a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schell M J, Molliver M E, Snyder S H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3948–3952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campistron G, Buijs R M, Geffard M. Brain Res. 1986;376:400–405. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pow D V, Crook D K. J Neurosci Methods. 1993;48:51–63. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(05)80007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ottersen O P, Storm-Mathisen J, Madsen S, Skumlien S, Stromhaug J. Med Biol. 1986;64:147–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lan H Y, Mu W, Ng Y Y, Nikolic-Paterson D J, Atkins R C. J Histochem Cytochem. 1996;44:281–287. doi: 10.1177/44.3.8648089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schaeren-Wiemers N, Gerlin-Moser A. Histochemistry. 1993;100:431–440. doi: 10.1007/BF00267823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Degerling A, Friberg K, Bean A J, Hökfelt T. Histochemistry. 1992;98:39–49. doi: 10.1007/BF00716936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones M E, Anderson A D, Anderson C, Hodes S. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1961;95:499–507. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(61)90182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krebs H A, Henseleit K. Hoppe-Seyler’s Z Physiol Chem. 1932;210:33–66. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dwyer M A, Bredt D S, Snyder S H. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;176:1136–1141. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)90403-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pasqualotto B A, Hope B T, Vincent S R. Neurosci Lett. 1991;128:155–160. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90250-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodrigo J, Springall D R, Uttenthal O, Bentura M L, Abadia-Molina F, Riveros-Moreno V, Martinez-Murillo R, Polak J M, Moncada S. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B. 1994;345:175–221. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1994.0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bredt D S, Glatt C E, Hwang P M, Fotuhi M, Dawson T M, Snyder S H. Neuron. 1991;7:615–624. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90374-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baek K J, Thiel B A, Lucas S, Stuehr D J. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:21120–21129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bredt D S, Hwang P M, Snyder S H. Nature (London) 1990;347:768–770. doi: 10.1038/347768a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brenman, J. E., Xia, H., Chao, D. S., Black, S. M. & Bredt, D. S. Dev. Neurosci., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Hecker M, Mulsch A, Busse R. J Neurochem. 1994;62:1524–1529. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62041524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGregor A, Herber J. Brain Res. 1992;574:9–20. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90793-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nelson R J, Demas G E, Huang P L, Fishman M C, Dawson V L, Dawson T M, Snyder S H. Nature (London) 1995;378:383–386. doi: 10.1038/378383a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dalkara T, Moskowitz M A. Brain Pathol. 1994;4:49–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1994.tb00810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ashwal S, Cole D J, Osborne T N, Pearce W J. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 1993;5:241–249. doi: 10.1097/00008506-199310000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nowicki J P, Duval D, Poignet H, Scatton B. Eur J Pharmacol. 1991;204:339–340. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90862-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang Z, Huang P L, Panahian N, Dalkara T, Fishman M C, Moskowitz M A. Science. 1994;265:1883–1885. doi: 10.1126/science.7522345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]