Abstract

Immunoliposomes, directed to clinically relevant cell-surface molecules with antibodies, antibody fragments or peptides, are used for site-specific diagnostic evaluation or delivery of therapeutic agents. We have developed intrinsically echogenic liposomes (ELIP) covalently linked to fibrin(ogen)-specific antibodies and Fab fragments for ultrasonic imaging of atherosclerotic plaques. In order to determine the effect of liposomal conjugation on the molecular dynamics of fibrinogen binding, we studied the thermodynamic characteristics of unconjugated and ELIP-conjugated antibody molecules. Utilizing radioimmunoassay and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay protocols, binding affinities were derived from data obtained at three temperatures. The thermodynamic functions ΔH°, ΔG° and ΔS° were determined from van't Hoff plots and equations of state. The resultant functions indicated that both specific and nonspecific associations of antibody molecules with fibrinogen occurred through a variety of molecular interactions, including hydrophophic, ionic and hydrogen bonding mechanisms. ELIP conjugation of antibodies and Fab fragments introduced a characteristic change in both ΔH° and ΔS° of association, which corresponded to a variable contribution to binding by phospholipid gel-liquid crystal phase transitions. These observations suggest that a reciprocal energy transduction, affecting the strength of antibody-antigen binding, may be a singular characteristic of immunoliposomes, having utility for optimization and further development of the technology.

Keywords: Immunoliposome, Radioimmunoassay, ELISA, Thermodynamics, Phospholipid phase transition

1. Introduction

Immunoliposomes “targeted” to various molecular structures with specific ligands, such as antibodies and peptides, have been developed for a number of therapeutic and diagnostic applications [1-12]. The success of liposomal targeting in these studies was usually assessed by determination of ligand quantity coupled to the liposomes (conjugation efficiency), an in vitro measure of liposomal ligand association with target molecules (targeting efficiency), and a demonstration of liposomal targeting within the context of the intended application, in vitro and/or in vivo. Although immunoliposome affinities have been measured in several studies [13,14], the effect of liposomal conjugation on molecular ligand-target interactions has not been examined.

The measurement and analysis of the thermodynamic characteristics of noncovalent molecular interactions provides valuable information, such as the contribution to association energetics of solvation, protonation, apolar van der Waal's forces, hydrogen bonds, ionic interactions and motion constraints [15-21]. For instance, a two-step kinetic mechanism in which an initial association of hen egg white lysozyme with its specific antibody was followed by rearrangement to a more stable state was implicated from Gibbs Free Energies (ΔG) determined from surface plasmon resonance (SPR)-derived affinities [22]. Dissociation kinetics of a self-aggregating humanized monoclonal antibody specific for vascular endothelial growth factor were determined by size-exclusion high-pressure liquid chromatography at different temperatures, while standard thermodynamic functions were calculated from equations of state, enabling the authors to conclude that aggregation depended largely on hydrophobic interactions [23].

Scatchard analysis of data obtained by radioimmunoassay (RIA) methods, including double-antibody [24,25] and gel filtration [26-28] separation protocols, has been employed frequently for determination of antibody-antigen binding affinities [29-31]. Enzyme immunoassays, including ELISA, have also been used to determine affinities, but the validity of these methods for such purposes has been subject to some controversy. The method utilized by Edgell et al. [32] for a direct ELISA aimed to determine apparent dissociation constants (KD) of interactions between antibodies and immobilized fibrin, which approximates the ultimate application of the monoclonal antibodies examined. This method, relying on the hyperbolic function that defines the ELISA dose-response, requires that the final absorbance values obtained directly reflect the quantity of antibody bound to the immobilized antigen, a condition that has been confirmed by several investigators [33,34]. Underwood [35] criticized the use of direct ELISA for determining affinities, pointing out that the secondary enzyme-labeled antibody incubations employed in most ELISA protocols perturb the equilibrium achieved during the primary antibody-antigen reactions. This effect could be normalized, however, through application of equations describing the phenomenon, provided that the concentration of immobilized antigen is known.

We have developed intrinsically echogenic liposomes (ELIP) for diagnostic marker targeting to atheroma in various stages of development, employing ultrasonic imaging procedures [36], and subsequently demonstrated effective targeting of echogenic immunoliposomes (EGIL), produced by conjugating ELIP to various antibody preparations via a thioether linkage, in vitro [37] and in vivo [38]. In the latter case, early- and late-stage atheromas in Yucatan miniswine were highlighted by transvascular and intravascular ultrasound procedures, utilizing ELIP conjugated to antibodies specific for intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and fibrin(ogen). Optimal fibrin targeting of ELIP has been quantitatively defined in vitro by retention of immobilized liposomes in a flow circuit under physiologically simulated conditions [39].

A better understanding of molecular EGIL-antigen (Ag) association dynamics may enable optimization of the conjugation procedure toward improving EGIL targeting efficiency. This study was intended to determine the effect of ELIP conjugation on antifibrin(ogen)-fibrinogen affinities and the thermodynamically inferred nature of the interactions. The results based on a double-antibody RIA procedure were compared with those derived from a direct ELISA, corrected for shifts in equilibrium conditions during a final secondary antibody-enzyme conjugate incubation. Clinical applicability of the derived information was tested in a preliminary fashion by repetition of an ELISA study using serum as the sample diluent.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation and Characterization of EGIL

ELIP, consisting of egg L-α-phosphatidylcholine (PC), 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[4-(p-maleimidophenyl)butyrate] (MPB-PE), 1,2 dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol (DPPG) and cholesterol (CH) in a 60:8:2:30 or 69:8:8:15 molar ratio, were prepared by a dehydration-rehydration method and conjugated to proteins as previously described [36,37,40]. The intact antibodies conjugated were a rabbit polyclonal IgG fraction that reacts equally well with human fibrin and fibrinogen (PA-fgn), a mouse monoclonal anti-human fibrin(ogen) with similar cross-reactivity (MA-fgn) and a mouse monoclonal antibody specific for human fibrin (MA-fb). All antibody preparations were obtained from American Diagnostica, Inc. (Greenwich, CN). Thiolated IgG or Fab prepared from 2 mg Ab was reacted with 29 mg ELIP lipid. Fab fragments were prepared from MA-fgn using a commercial kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For the RIA studies, conjugation efficiency (CE) was determined by adding a tracer quantity (3 μCi) of 125I-labeled anti-rabbit Ig to PA-fgn in a typical conjugation protocol and monitoring activity of column fractions during purification of SPDP-activated protein, reduced thiolated protein and protein-conjugated ELIP with a Cobra 5005 Gamma Counting System (Packard Instr. Co., Downers Grove, IL). For the ELISA studies, CE was determined by a quantitative IgG immunoblot assay as described by Klegerman et al. [40]. EGIL were sized and enumerated with a Coulter Multisizer II fitted with a 15 μm aperture tube, which enabled particle sizing down to 0.3 μm equivalent spherical diameter.

2.2. Radioimmunoassay

For characterization of unconjugated antibody-antigen interactions, a double-antibody RIA protocol was developed using 125I-fibrinogen (fgn*; Amersham Life Sci., Arlington Heights, IL), unlabeled human fibrinogen (Calbiochem-Novabiochem Corp., SanDiego, CA) and specific antibody (0.1 μg fgn*/μg Ab). For PA-fgn, antibody-bound fibrinogen was separated from free fibrinogen with goat anti-rabbit gamma globulin, while fibrinogen bound by MA-fgn and Fab was precipitated with goat anti-mouse gamma globulin. Precipitation was facilitated by addition of carrier rabbit or mouse serum. Optimal concentrations of precipitating reagents were specified by the manufacturer (Calbiochem) or determined in preliminary experiments. Triplicate determinations were made. The time required to attain equilibrium conditions at three temperatures was determined in preliminary experiments. These were: 3 days primary Ab incubation + 2 days secondary Ab incubation at 4° C, 2 + 1 day at 24° C, and 1 day + overnight at 37° C. Sodium azide (0.1 percent) was included in the incubation buffer at 24 and 37° C and was shown not to influence the association behavior of the reaction components.

For RIA of immunoliposomes, EGIL were incubated with fgn* (0.5 μg EGIL Ab/μg fgn*) in the presence of increasing quantities of unlabeled human fibrinogen at various temperatures (duplicate determinations: 4° C for 4 days; 25° C for 3 days; 37° C for 2 days). Each reaction solution (1.0 ml) was then applied to 20 ml of Sepharose 4B in an EconoPac column (Bio-Rad Life Sci., Hercules, CA) and eluted with barbital-acetate buffer, pH 7.4. It was established that EGIL-bound fgn* eluted in the first 8.3 ml and intact free fibrinogen in the next 7.4 ml. The column flow rate was 56 ml per hour and, therefore, the bound fraction was recovered within ten minutes, resulting in negligible underestimation of this fraction due to the gel filtration method [41].

2.3. ELISA

Wells of immunoassay grade 96-well microtiter plates (Fisher Scientific) were coated with 50 μg/ml of human fibrinogen (Fgn; Calbiochem) in 0.05M sodium bicarbonate, pH 9.6, overnight at 4° C. All incubation volumes were 50 μl. One well per sample dilution was left uncoated for determination of nonspecific binding. After aspirating well contents, all wells were blocked with conjugate buffer (1% bovine serum albumin in 0.05M Tris buffer, pH 8.0, with 0.02% sodium azide) for 1 hour. From this point, all incubations were at 37° C (except for thermodynamic studies, where the primary Ab incubation was carried out at three temperatures), followed by aspiration of well contents and washes (3X) with PBS-T (0.02M phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4, with 0.05% Tween 20). Half the wells were converted to fibrin by incubating them with 1U/ml of thrombin in PBS-T with 0.56U aprotinin/ml for 20 minutes. The remaining wells (fgn) were incubated with PBS-T alone. For assay of intact EGIL, wells were washed with PBS after this incubation and the first wash after the EGIL incubation was also with PBS. Various dilutions of Ab (in PBS-T) or EGIL (in PBS) were incubated for 2 hours, followed by a 1-hour incubation with 1:1,000 secondary Ab-alkaline phosphatase (AP) in conjugate buffer. The secondary Ab was goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG (Bio-Rad Labs). The substrate incubation consisted of 50 μl of substrate buffer (0.05M glycine buffer, pH 10.5, with 1.5mM magnesium chloride) + 50 μl p-nitrophenyl phosphate (4 mg/ml; Sigma Chem. Co.) in substrate buffer per well for 15 minutes. The reaction was stopped with 50 μl 1M sodium hydroxide per well. The optical absorbance of each well at 405nm (A405) was measured with a Multiskan MCC/340 microplate reader. Net A405 was determined by subtracting the absorbance of control wells from that of antigen (Ag) wells.

2.3.1. Serum ELISA Study

In order to approximate the effects of in vivo conditions on Ab-Ag binding characteristics, the ELISA protocol for both unconjugated and ELIP-conjugated PA-fgn was repeated using undiluted normal rabbit serum (NRS; Sigma-Aldrich) as sample diluent instead of PBS-T/PBS during the primary Ab incubation. PBS washes were employed as for EGIL incubations.

2.4. Calculations

2.4.1. RIA studies

For unconjugated antibody,

| (1) |

where CPM = counts per minute and NSB = nonspecific binding (B CPM at an excess [100 μg] of unlabeled fgn).

| (2) |

For EGIL RIA, B was adjusted for the fraction of total I-125 activity recovered from the column. Scatchard plots were prepared by graphing B/F vs. B (in molar concentration based on a fgn molecular weight of 340 kDa). Multiple affinities (Kassoc) were determined from the slopes of discernable linear segments of the plots. For each affinity, standard enthalpy change, ΔH°, was determined from the slope of a plot of logK vs. 1/T, according to the van't Hoff equation, expressed as

| (3) |

The standard Gibbs free energy increment, ΔG°, was calculated from

| (4) |

and the standard entropy change, ΔS°, was then determined from

| (5) |

which was verified by comparison with ΔS° derived from the y-intercept of the van't Hoff plot.

2.4.2. ELISA studies

The dissociation constant (KD) of Ab or EGIL binding to Ag was calculated according to the equation,

| (6) |

which defines a 2-parameter single rectangular hyperbola, where A = Net A405 and L = Ab [32]; [Ab] for EGIL was calculated from the CE. KD was determined as the average of two computational methods, both performed using SigmaPlot 2000 software: a) the b-parameter of a hyperbolic fit of the data (SPHR), which is the x-intercept of half-maximal y (Amax), and b) the slope of a plot of Amax/A vs. 1/[L] (reciprocal plot), based on a linear transform of the hyperbola:

| (7) |

For polyclonal Ab, the plot was non-linear and best fit was achieved with a binomial regression using Sigmaplot 2000 software. The range of affinities was defined by minimal and maximal slopes from tangents drawn to the curve. In that case, the arithmetic mean of the range was used as the reciprocal plot KD value.

The KD values thus obtained were corrected for perturbation of equilibrium conditions during the secondary Ab-AP incubation, as defined by Underwood [35]:

| (8) |

where [Ab] is the original total molar Ab concentration in the ELISA well, [Ag] is the total molar concentration of Ag epitopes on the solid phase for this particular Ab, α is the proportion of Ab bound to Ag at equilibrium and β is the proportion of remaining Ab (α[Ab]) that remains bound after the secondary Ab-AP incubation. Assuming that α ∼ 0.5 at [Ab] = KD, the equation could be solved for β at that point, provided [Ag] is known. That value was determined to be 5 nM for fibrin(ogen) under the conditions of the ELISA from Scatchard analysis of a solid-phase fibrin-tPA activity assay (SOFIA-tPA) utilizing the same fgn coating parameters [42]. Since β = A/Amax, apparent KD values were calculated from equation (6), as

| (9) |

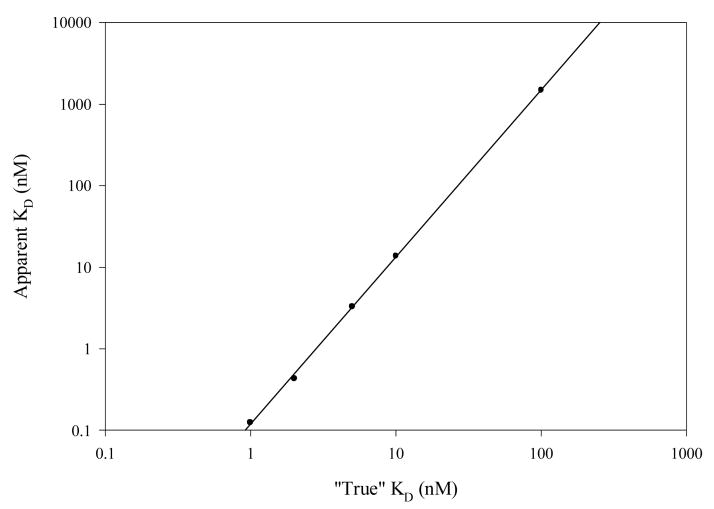

for five “true” KD values in the range 0.5-100 nM. The resultant log-log linear regression of true vs. apparent KD values was used to correct the ELISA KD results (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Correction nomogram for ELISA apparent affinities. Linear regression: r = 0.9998; log y = 2.05 log x − 0.930.

3. Results

3.1. Unconjugated Polyclonal Rabbit Anti-Fibrin(ogen)(PA-fgn)

3.1.1. Radioimmunoassay (RIA) Data

The nonspecific binding (NSB) of labeled fibrinogen to gamma globulin in the absence of primary antibody was large (19-42 percent), but was found to be mostly reversible and ionic in nature, being reduced to 11-30 percent by including 0.5 M sodium chloride in the incubation buffer. The true NSB was shown to be 8-17 percent by addition of an excess of unlabeled fibrinogen (fgn) to the incubation solution.

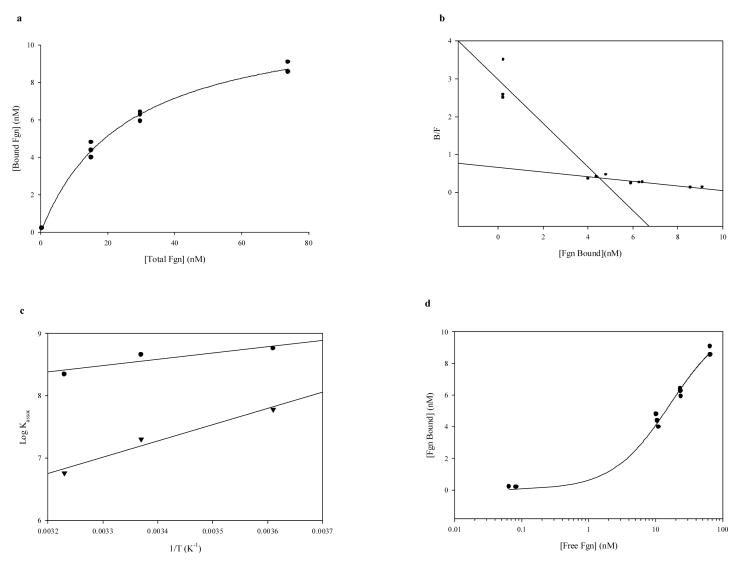

Plots of antibody-bound labeled fgn vs. increasing unlabeled fgn added at all three temperatures (dose-response curves, not shown) indicated competitive protein binding behavior, which was found to be saturable (Fig. 2a). Scatchard plots (Fig. 2b) of these data revealed two major affinity ranges: high (in the order of 108 M−1) and low (in the order of 106-107 M−1)(Table 1). The accuracy of high-affinity determinations below the first unlabeled fgn standard (5.0 μg) was verified (at 37°C) by repeating the determination < 10 μg with two additional standards (1.0 and 2.0 μg). The plot was linear and the resultant Kassoc of 2.60 × 108 M−1 agreed well with the value of 2.23 × 108 M−1 derived from the B0 and 5 μg fgn points. Antibody occupancy (number of binding sites per molecule antibody) significantly exceeded two only for the lowest affinity interaction at 37°C, indicating that nonspecific associations began to predominate under those conditions. Klotz [43] had cautioned that the concentration of ligand binding sites [n] derived from Scatchard plots needs to be verified by sufficient data. Based on his recommendation, a plot of B vs. logF for the 4°C data (fig. 2d) shows that the inflection point had clearly been passed and occurred at about 6 nM bound fgn. The maximum n of 14.1 nM fgn bound is more than twice this value. Inflection points were even more clearly seen on analogous plots of data obtained at higher temperatures (not shown).

Fig. 2.

Determination of thermodynamic functions for unconjugated polyclonal rabbit anti-human fgn-fgn binding: RIA Data. a. Saturation isotherm of fgn RIA data at 4°C; hyperbolic fit [r = 0.997; y = 11.73x/(25.69 + x)]. b. Scatchard plot of data from a. c. van't Hoff plot of fgn RIA data: linear regressions; circles are high-affinity associations, inverted triangles are low-affinity associations. d. B vs. logF plot for test of [n] validity; 4°C data.

TABLE 1.

Unconjugated Anti-Fibrin(ogen)/Fibrinogen Binding Characteristics

| RIA | ELISA | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temp.

(°C) |

Kassoc (M−1) |

No. Bind.

Sites/Mol. Ab |

ΔH°

(kcal/mole) |

ΔG°

(kcal/mole) |

ΔS°

(cal/mole°) |

Apparent

Kassoc (M−1) |

“True”

Kassoc (M−1) |

ΔH°

(kcal/mole) |

ΔG°

(kcal/mole) |

ΔS°

(cal/mole°) |

|

| 4 | 5.77×108 | 0.77 | −4.65 | −11.10 | +23.31 | 5.55 × 107 | 8.59 × 107 | −1.05 | −10.06 | +32.50 | |

| 6.06×107 | 2.12 | −11.93 | −9.86 | −7.46 | |||||||

| 24/23 | 4.55×108 | 0.44 | −4.65 | −11.77 | +23.97 | 4.56 × 107 | 7.80 × 107 | −1.05 | −10.69 | +32.55 | |

| 2.02×107 | 1.78 | −11.93 | −9.93 | −6.73 | |||||||

| 37 | 2.23×108 | 0.49 | −4.65 | −11.84 | +23.21 | 3.65 × 107 | 7.00 × 107 | −1.05 | −11.13 | +32.50 | |

| 5.80×106 | 5.26 | −11.93 | −9.59 | −7.53 | |||||||

Van't Hoff plots of the data (Fig. 2c) revealed moderate negative enthalpy changes for the high-affinity interactions and high negative enthalpy changes for the low-affinity interactions. Standard entropy changes derived from these parameters (which agreed well with values calculated from the y-intercept of the van't Hoff plots) were highly positive for the high-affinity interactions and moderately negative for the low-affinity interactions (Table 1), supporting the conclusion that the high affinities describe a specific Ab-Ag association in which hydrophobic interactions play a prominent role, while the lower affinities reflect a “nonspecific” ionic interaction.

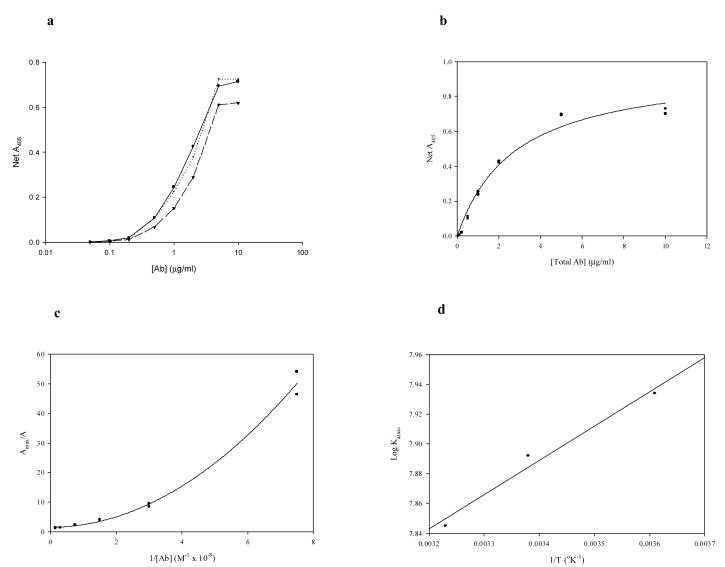

3.1.2. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) Data

The ELISA data for the unconjugated PA-fgn illustrates that the resultant net optical densities at 405 nm define a hyperbolic relation (Fig. 3b) that is basic to the analysis of Edgell et al. [32]. The reciprocal plots of the dose-response data (Fig. 3c) are non-linear, as expected for a polyclonal Ab preparation. The extrema of these plots are in the range of 106 and 107-8 M−1, suggesting that the strong nonspecific IgG-fibrin(ogen) association also contributed to the ELISA results, since the background correction involved nonspecific Ab binding to albumin. This hypothesis seems to be supported by the ELISA-derived average corrected affinities, which lay between the RIA extrema (Table 1). The arithmetic average of the extrema, in fact, were consistently in very good agreement with the SPHR-derived value. The standard enthalpy (ΔH°) and entropy (ΔS°) changes calculated from these affinities are more characteristic of hydrophobic interactions than those of the higher RIA affinities, however, rather than being intermediate between the two types of interactions.

Fig. 3.

Determination of thermodynamic functions for unconjugated polyclonal rabbit anti-human fgn-fgn binding: ELISA Data. a. Semi-log dose-response curves at all three temperatures; circles, solid line: 4°C; circles, dotted line: 23°C; inverted triangles, dashed line: 37°C. b. Dose response at 4°C, hyperbolic fit [r = 0.990; y = 0.974x/(2.767 + x)]. c. Linear transform (reciprocal plot) of data from b, quadratic fit [r = 0.996; y = 0.860x2 + 0.045x + 1.518]. d. van't Hoff plot of corrected ELISA affinities.

3.2. ELIP-Conjugated PA-fgn

3.2.1. RIA Data

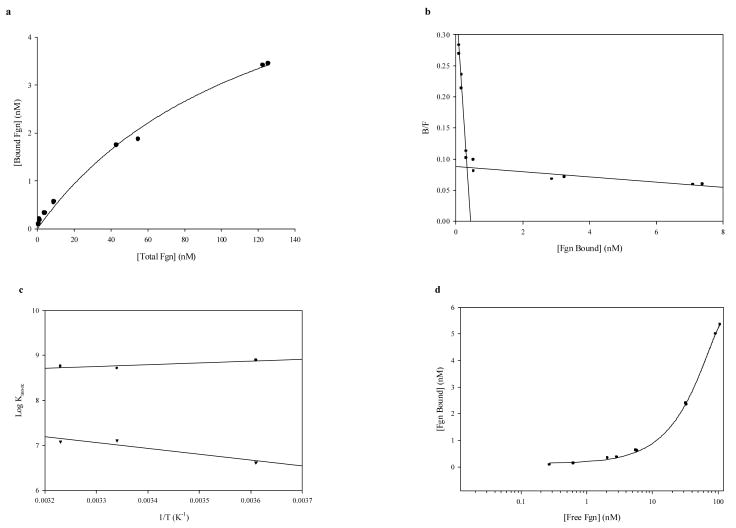

125I-IgG radiotracer methodology enabled us to estimate the antibody yields at each stage of the conjugation procedure: 80 percent after Sephadex G-50 separation of thiolated Ab; 62 percent after G-50 separation of reduced thiolated protein; and 3.9 percent of starting Ab finally coupled to ELIP. Coulter Multisizer analysis of PAfgn-ELIP indicated a yield of 8.2 × 109 liposomes, exhibiting a number-average diameter of 854 nm. The conjugation efficiency (CE), therefore, was 1.35 × 104 Ab molecules per liposome, or 8.1 μg Ab/mg lipid. Based on an area of 11.34 nm2 subtended by the Fc portion of IgG [44], Ab molecules would cover 66 percent of the available liposomal surface area occupied by PE.

The fgn association behavior of ELIP-conjugated PA-fgn, which also fell into two major affinity ranges, was in many respects very similar to that of the unconjugated Ab (Fig. 4, Table 2). While the highest affinity specific interactions involved less than 20 percent of the available Ab, the lower affinity associations far exceeded the conjugated Ab, indicating that they were dominated by nonspecific interactions. Plots of B vs. logF (Fig. 4d) confirmed the accuracy of Ab occupancy information. As in the case of the unconjugated Ab, the specific associations were moderately exothermic, but the standard entropy increase was about 10 cal/mole° higher (Table 2). The thermodynamic properties of the low-affinity interactions, however, appear to be radically different, having become endothermic with a very high positive entropy change, suggesting a liposomal contribution to the Ab-Ag binding energetics.

Fig. 4.

Determination of thermodynamic functions for EGIL-conjugated polyclonal rabbit anti-human fgn-fgn binding: RIA Data. a. Saturation isotherm of fgn RIA data at 26°C; hyperbolic fit [r = 0.996; y = 6.892x/(127.3 + x)]. b. Scatchard plot of RIA data at 4°C. c. van't Hoff plot of Afgn-EGIL RIA data: linear regressions; circles are high-affinity associations, inverted triangles are low-affinity associations. d. B vs. logF plot for test of [n] validity; 37°C data.

TABLE 2.

Anti-Fibrin(ogen)-Conjugated ELIP/Fibrinogen Binding Characteristics

| RIA | ELISA | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temp.

(ºC) |

Kassoc (M−1) |

No.

Site/Lip. × 103 |

%

Tot. Ab |

ΔH°

(kcal/mole) |

ΔG°

(kcal/mole) |

ΔS°

(cal/mole°) |

Apparent

Kassoc (M−1) |

“True”

Kassoc (M−1) |

ΔH°

(kcal/mole) |

ΔG°

(kcal/mole) |

ΔS°

(cal/mole°) |

| 4 | 7.81 × 108 | 2.21 | 16.4 | −1.90 | −11.27 | +33.81 | 4.35±0.72

× 107 |

7.61±0.61

×107 |

−0.37±1.20 | −9.99

±0.04 |

+34.84

±4.42 |

| 4.23 × 106 | 103 | 766 | +5.99 | −8.40 | +51.92 | ||||||

| 26/20 | 5.13 × 108 | 2.65 | 19.6 | −1.90 | −11.92 | +33.48 | 6.60±3.20

× 107 |

9.15±2.16

×107 |

−0.37±1.20 | −10.66

±0.13 |

+35.24

±4.53 |

| 1.30 × 107 | 26.7 | 198 | +5.99 | −9.73 | +52.57 | ||||||

| 37 | 5.73 × 108 | 2.69 | 19.9 | −1.90 | −12.42 | +33.93 | 4.24±2.73

× 107 |

7.28±2.16

×107 |

−0.37±1.20 | −11.13

±0.17 |

+34.83

±4.41 |

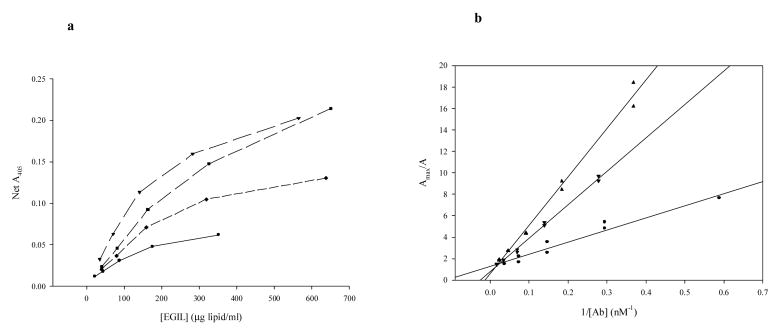

3.2.2. ELISA Data

Four different PAfgn-ELIP preparations were assayed and analyzed, resulting in corrected affinities and thermodynamic functions that exhibited relatively low variance (Table 2). Unlike the unconjugated Ab, the reciprocal plots for Ab-ELIP were linear (Fig. 5b), but—like the unconjugated Ab—the affinities were intermediate between the RIA extremes, while the ΔH° and ΔS° values were similar to the corresponding functions for the high-affinity RIA data, as well as for the unconjugated Ab ELISA data.

Fig. 5.

Determination of affinities for EGIL-conjugated polyclonal rabbit anti-human fgn-fgn binding: ELISA Data. a. Dose-response curves for four different EGIL preparations. b. Linear transforms (reciprocal plots) of data from a, linear regressions.

3.3. Unconjugated Monoclonal Anti-Fibrin(ogen)(MA-fgn)

3.3.1. RIA Data

A single Kassoc. was determined by linear regression analysis at each temperature (r = −0.934 to −0.971) and was in the range 107-8 (Table 3). The three Scatchard plots converged at an Ab occupancy of 1.39 ± 0.03 binding sites per molecule Ab. The MAb affinities and occupancy values were intermediate between those of two major classes of PAb reported above. The thermodynamics of MAb binding, featuring a relatively large negative enthalpy and a moderate positive entropy (Table 3), indicate that the MAb utilizes a combination of several types of noncovalent interactions to bind fgn.

TABLE 3.

Unconjugated Monoclonal Anti-Fibrin(ogen)/Fibrinogen Binding Characteristics

| RIA | ELISA | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temp.

(ºC) |

Kassoc (M−1) |

No. Bind.

Sites/Mol. Ab |

ΔH°

(kcal/mole) |

ΔG°

(kcal/mole) |

ΔS°

(cal/mole°) |

Apparent

Kassoc (M−1) |

“True”

Kassoc (M−1) |

ΔH°

(kcal/mole) |

ΔG°

(kcal/mole) |

ΔS°

(cal/mole°) |

| 4 | 2.15×108 | 1.34 | −7.53 | −10.56 | +10.95 | 8.42 × 108 | 3.23 × 108 | −3.52 | −10.78 | +26.21 |

| 24/23 | 1.27×108 | 1.39 | −7.53 | −11.01 | +11.74 | 4.91 × 108 | 2.48 × 108 | −3.52 | −11.37 | +26.50 |

| 37 | 4.73×107 | 1.43 | −7.53 | −10.89 | +10.84 | 2.02 × 108 | 1.61 × 108 | −3.52 | −11.64 | +26.18 |

3.3.2. ELISA Data

The reciprocal plots were linear; affinities calculated from the ELISA data were very similar to those calculated from the RIA data (Table 3), but with a shallower slope vs. temperature, resulting in about half the exothermic enthalpy increment. Like the unconjugated PA-fgn, the ELISA-derived ΔS° was appreciably greater than the RIA-derived value.

3.4. ELIP-Conjugated MA-fgn

3.4.1. RIA Data

MAfgn-ELIP comprised 3.31 × 1010 recovered ELIP (dn = 637nm) conjugated to 41.8 μg Ab, resulting in a CE of 5.07 × 103 molecules per liposome or 4.3 μg Ab/mg lipid; 56 percent of available PE was coupled to Ab. The predominant higher-affinity Ab-Ag interactions were lower than the unconjugated MA-fgn and included nonspecific associations that supersaturated the available EGIL surface Ab (Table 4). Like the average of specific and nonspecific PAfgn-ELIP associations, these interactions were characterized by positive enthalpies and very high positive entropies.

TABLE 4.

Monoclonal Anti-Fibrin(ogen)-Conjugated ELIP/Fibrinogen Binding Characteristics

| RIA | ELISA | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temp.

(ºC) |

Kassoc (M−1) |

No.

Site/Lip. × 103 |

%

Tot. Ab |

ΔH°

(kcal/mole) |

ΔG°

(kcal/mole) |

ΔS°

(cal/mole°) |

Apparent

Kassoc (M−1) |

“True”

Kassoc (M−1) |

ΔH°

(kcal/mole) |

ΔG°

(kcal/mole) |

ΔS°

(cal/mole°) |

| 4 | 1.08 × 107 | 32.6 | 642 | +3.05 | −8.91 | +43.19 | 5.65 × 109 | 8.19 ×108 | +1.61 | −11.30 | +46.60 |

| 25/23 | 1.23 × 107 | 21.9 | 433 | +3.05 | −9.67 | +42.67 | 7.69 × 109 | 9.52 ×108 | +1.61 | −12.16 | +46.52 |

| 37 | 2.05 × 107 | 15.4 | 303 | +3.05 | −10.37 | +43.29 | 1.07×1010 | 1.12 ×109 | +1.61 | −12.84 | +46.60 |

3.4.2. ELISA Data

As with the unconjugated MAb, the reciprocal plots were linear. In this case, the affinities determined by ELISA were strikingly disparate from those found by RIA, being two orders of magnitude higher. Yet, the ΔH° and ΔS° values were very similar to the corresponding functions for the RIA data (Table 4).

3.5. Monoclonal Anti-Fibrin(ogen) Fab (RIA Data Only)

3.5.1. Unconjugated MA-fgn Fab

The characteristics of Fab-fgn interactions are summarized in Table 5. Whereas a single Kassoc was found at each temperature for MAfgn-fgn interactions, up to two were found for the Fab. The higher Kassoc values at 4 and 25°C (indiscernible at 37°C) were similar to the corresponding values for MAfgn, suggesting that the lower Kassoc values represent unusually strong nonspecific interactions. This possibility is supported by high binding of 125I-fgn to Fab in the presence of 100 μg unlabeled fgn (∼25 percent). The Scatchard plots (not shown) indicate, based on the occupancy data ([n]), that 4-5 Fab molecules bind to each fgn molecule specifically, while 2-3 Fab associate with each fgn molecule nonspecifically. The thermodynamic profiles of the putative nonspecific interactions are now more indicative of hydrophobic interactions, suggesting that removal of the Fc fragment may have exposed apolar residues. Although the specific affinities are similar to those of the parent MAb, the thermodynamic profile is more characteristic of an ionic interaction, suggesting that the proteolytic cleavage may have caused an allosteric modification of the antigen-binding site.

TABLE 5.

Monoclonal Anti-Fibrin(ogen) Fab/Fibrinogen Binding Characteristics – RIA Data

| Unconjugated | Conjugated | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temp.

(ºC) |

Kassoc (M−1) |

No. Bind.

Sites/Mol. Fab |

ΔH°

(kcal/mole) |

ΔG°

(kcal/mole) |

ΔS°

(cal/mole°) |

Kassoc (M−1) | No. Site/Lip.

× 103 |

%

Tot. Ab |

ΔH°

(kcal/mole) |

ΔG°

(kcal/mole) |

ΔS°

(cal/mole°) |

| 4 | 3.06×108 | 0.23 | −10.44 | −10.75 | +1.13 | 6.93 × 107 | 46.2 | 89.8 | −2.04 | −9.94 | +28.51 |

| 1.35 × 107 | 195 | 379 | −2.22 | −9.04 | +24.61 | ||||||

| 8.11×107 | 0.38 | −7.50 | −10.02 | +9.12 | 5.98 × 106 | 377 | 733 | −1.55 | −8.59 | +25.39 | |

| 25/26 | 8.56×107 | 0.21 | −10.44 | −10.82 | +1.26 | 5.23 × 107 | 62.0 | 121 | −2.04 | −10.56 | +28.49 |

| 2.02×107 | 0.43 | −7.50 | −10.12 | +8.80 | 9.98 × 106 | 233 | 454 | −2.22 | −9.60 | +24.60 | |

| 37 | 2.02×107 | 0.35 | −7.50 | −10.36 | +9.24 | 4.70 × 107 | 59.0 | 115 | −2.04 | −10.88 | +28.52 |

| 4.45 × 106 | 425 | 826 | −1.55 | −9.43 | +25.40 | ||||||

3.5.2. ELIP-Conjugated MA-fgn Fab

MafgnFab-ELIP comprised 1.28 × 1010 recovered ELIP (dn = 1,030nm) conjugated to 48.0 μg Fab, resulting in a CE of 5.14 × 104 molecules per liposome or 5.0 μg Fab/mg lipid (8.5 μg Ab equivalent/mg lipid); 61 percent of available PE was coupled to Fab. Only the highest affinities at each temperature represent specific interactions, involving virtually all of the liposomal Fab (Table 5). Nonspecific binding to the liposomes involved more than eightfold greater amounts of fgn, exceeding by more than threefold the theoretical maximum amount of surface area available for fgn binding (based on known end-on dimensions of the fgn molecule). These findings suggest that Ag-Ag interactions may also be involved in nonspecific binding of fgn to EGIL. The affinity of the specific interactions was 2-6 times higher than that found for the higher affinity MAfgn-ELIP/fgn associations (Table 4), which seem to correspond to the midrange Fab affinities, suggesting that the highest affinity interactions were not detected for the MAfgn-ELIP. As was the case for intact MAb, significant increases in ΔH° and ΔS° (in the positive direction) were seen upon ELIP conjugation of Fab, but the interaction remained exothermic in this instance (Table 5).

3.6. Monoclonal Anti-Fibrin (ELISA Data Only)

3.6.1. Unconjugated MA-fb

A great advantage of ELISA relative to RIA in this case is that it permits study of solid-phase fibrin systems that better approximate the intended application of fibrin-specific antibodies. An ELISA analysis of one such Ab is summarized in Table 6. All reciprocal plots for both the unconjugated Ab and Ab-ELIP were linear, with r > 0.95. The affinities and thermodynamic functions of the unconjugated MA-fb were very similar to those of the PA-fgn determined by ELISA analysis (Table 1), being indicative of strong hydrophobic interactions.

TABLE 6.

Monoclonal Anti-Fibrin/Fibrin Binding Characteristics – ELISA Data

| Unconjugated | Conjugated | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temp.

(ºC) |

Apparent

Kassoc (M−1) |

“True”

Kassoc (M−1) |

ΔH°

(kcal/mole) |

ΔG°

(kcal/mole) |

ΔS°

(cal/mole°) |

Apparent

Kassoc (M−1) |

“True”

Kassoc (M−1) |

ΔH°

(kcal/mole) |

ΔG°

(kcal/mole) |

ΔS°

(cal/mole°) |

| 4 | 1.22 × 108 | 1.26 × 108 | −2.73 | −10.27 | +27.20 | 1.45 × 107 | 4.47 × 107 | −2.89 | −9.70 | +24.57 |

| 23 | 1.16 × 108 | 1.23 × 108 | −2.73 | −10.96 | +27.79 | 1.42 × 107 | 4.41 × 107 | −2.89 | −10.35 | +25.21 |

| 37 | 3.80 × 107 | 7.14 × 107 | −2.73 | −11.14 | +27.12 | 4.30 × 106 | 2.45 × 107 | −2.89 | −10.48 | +24.48 |

3.6.2. ELIP-Conjugated MA-fb

ELIP conjugation of the Ab decreased the affinities by little more than one-half, with only minor changes in the thermodynamic functions. Unlike previous Abs studied, the functions became less hydrophobic in nature after conjugation (Table 6).

3.7. PA-fgn in Serum (ELISA Data Only)

3.7.1. Unconjugated PA-fgn

The affinity of unconjugated Ab binding to fibrinogen in NRS was at least as great as found by ELISA, using PBS-T as diluent, being 16 to 69 percent higher than previously found (Tables 1 and 7) over the temperature range studied. Although the interaction was now endothermic, there was no appreciable enthalpy change in either case and the difference may not be significant. Likewise, the entropy increments were within the same range (+32-40 cal/mole°).

TABLE 7.

Polyclonal Anti-Fibrin(ogen)/Fibrinogen Binding Characteristics in Rabbit Serum – ELISA Data

| Unconjugated | Conjugated | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temp.

(ºC) |

Apparent

Kassoc (M−1) |

“True”

Kassoc (M−1) |

ΔH°

(kcal/mole) |

ΔG°

(kcal/mole) |

ΔS°

(cal/mole°) |

Apparent

Kassoc (M−1) |

“True”

Kassoc (M−1) |

ΔH°

(kcal/mole) |

ΔG°

(kcal/mole) |

ΔS°

(cal/mole°) |

| 4 | 7.38 × 107 | 9.94 × 107 | +0.86 | −10.14 | +39.69 | 3.33 × 107 | 6.69 × 107 | −0.31 | −9.92 | +34.69 |

| 25 | 7.60 × 107 | 1.08 × 108 | +0.86 | −10.95 | +39.64 | 8.17 × 106 | 3.37 × 107 | −0.31 | −10.26 | +33.41 |

| 37 | 1.07 × 108 | 1.18 × 108 | +0.86 | −11.45 | +39.70 | 4.05 × 107 | 7.36 × 107 | −0.31 | −11.16 | +35.00 |

3.7.2. ELIP-Conjugated PA-fgn

The affinities and thermodynamic functions of PAfgn-ELIP/fgn in NRS fell well within the analogous populations (P > 0.1) of four other PAfgn-ELIP preparations in PBS at two comparable temperatures (4° and 37° C; Tables 2 and 7)

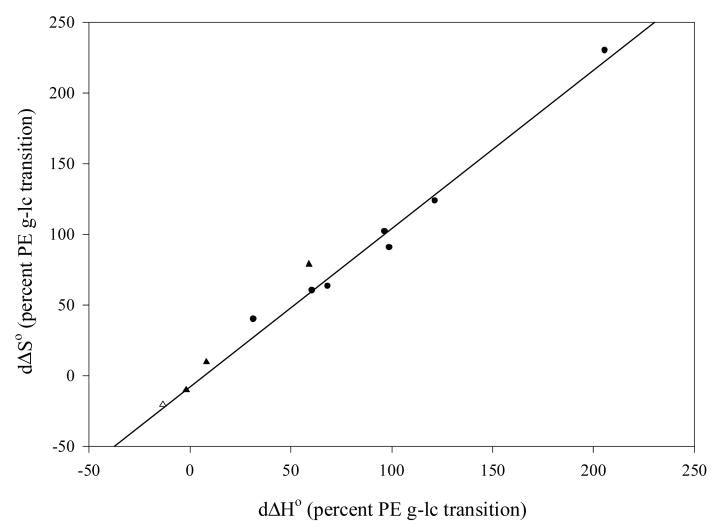

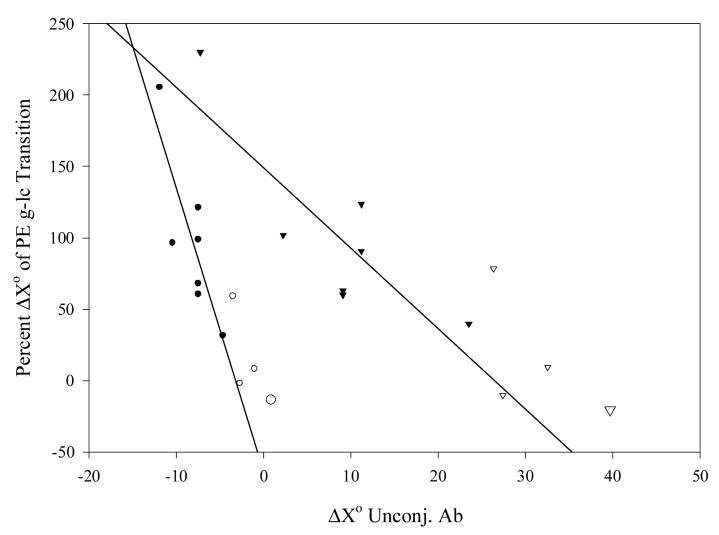

3.8. Relation of Thermodynamic Function Increments to Phospholipid Phase Transitions

In order to test the hypothesis that differences in ΔH° and ΔS° of Ab-Ag association after conjugation of Ab to ELIP are caused by linkage of the binding to the energetics of the PE gel-liquid crystal phase transition, the thermodynamic function increments were plotted against each other as percentages of published ΔH° (+8.71 kcal/mole) and ΔS° (+25.8 cal/mole°) values [45] for the transition in dipalmitoyl PE (Fig. 6). The plot demonstrates an excellent correlation, with a slope that does not differ significantly from 1.0 (P > 0.05), supporting the hypothesis. To determine whether coupling of transition energetics to Ab-Ag association kinetics was dependent on the type of interaction, ΔH° or ΔS° of the unconjugated Ab-Ag interaction was plotted relative to the corresponding percent function change of the transition (Fig. 7), which varied from a fractional exothermic liquid crystal → gel transition to the endothermic molar contribution of two PE molecules undergoing the phase transition. Significant inverse correlations (r ∼ 0.85, P ≤ 0.02) were seen for both ΔH° and ΔS°, suggesting that coupling is a function of ionic interactions. Data derived from PA-fgn/fgn interactions in normal rabbit serum (NRS) exhibited the same relationships in both plots as data derived from Ab-Ag interactions in non-serum containing diluents.

Fig. 6.

Correlation of standard enthalpy and entropy increments upon Ab-EGIL conjugation relative to corresponding values for the PE gel-liquid crystalline phase transition (r = 0.990, y = 1.095x – 3.17, Sb = 0.047); circles: RIA data, triangles: ELISA data; filled symbols: PBS-T/PBS diluent, open symbol: normal rabbit serum (NRS).

Fig. 7.

Interaction dependence of PE major phase transition coupling of Ab-Ag association energetics. Circles: X = H (kcal/mole), triangles: X = S (cal/mole°); filled symbols: RIA data, open symbols: ELISA data; large symbols: NRS.

4. Discussion

4.1. Binding of Unconjugated Antibodies to Human Fibrinogen and Fibrin

4.1.1. RIA studies elucidate nonspecific interactions

In this study, we have demonstrated two general classes of noncovalent interactions between polyclonal antibodies (PA-fgn) and human fibrinogen at three temperatures, utilizing standard RIA methodology followed by Scatchard and van't Hoff analyses. The higher affinity associations, in the order of 108 M−1, were characterized by Ab occupancies of less than one fgn binding site per molecule Ab and were dominated by hydrophobic interactions, indicating a specific Ab-Ag association. The lower affinity associations, in the order of 106-107 M−1, were characterized by Ab occupancies generally greater than two fgn binding sites per molecule Ab, were appreciably exothermic and exhibited negative ΔS°, suggesting nonspecific interactions dominated by ionic attractive forces. Specific fgn binding by a mouse monoclonal anti-fibrinogen Ab (MA-fgn) could be attributed more to ionic and hydrogen bond contributions, while removal of the Fc portion of the MA-fgn Ab appeared to shift specific binding to a more ionic character and produced a hydrophobically-driven nonspecific association.

A relatively high-affinity (∼6 × 106 M−1 at 37°C) nonspecific association between fibrinogen and immunoglobulins (Ig) would be expected to produce a significant effect in vivo. At physiologic concentrations of fgn and Ig, fgn would be completely adsorbed to Ig, while ∼ 3 percent of Ig would be bound to fgn, creating a “reservoir” functional quality, including relatively slow depletion kinetics, for fgn that is characteristic of effectors possessing carrier proteins. Since fgn affinity for Ig is about one order of magnitude higher than its strongest binding to thrombin [46], the fibrinopeptide cleavage sites of fgn would have to be fully exposed while bound by Ig. Despite its implications, there have been relatively few reports of this phenomenon. In serum, all fgn migrates electrophoretically as a β/γ globulin and, in fact, is located at the anodal edge of the γ-globulin zone [47], which would be expected for a more anionic protein complexed with Ig. Davey et al. [48] concluded that nonspecific protein interactions were responsible for prolongation of thrombin and reptilase clotting times in normal plasma and fgn solutions caused by addition of purified gamma globulin.

Recently, Ben-Ami et al. [49] reported indirect evidence (quantitation of red blood cell aggregation) for the formation of ternary complexes of Ig, fgn and albumin in vitro and in vivo. Such complex formation could have occurred in the RIA, since the diluent used for both primary and secondary incubations contained albumin, although concentrations of both albumin (0.35 percent) and fgn in the assay were well below threshold levels required for observable RBC aggregation. If ternary complex formation occurred, the lower affinity interactions observed in this study would describe binding of fgn to albumin that was, in turn, bound to Ig.

4.1.2. ELISA analysis can provide suitable binding data if potential artifacts are eliminated

Binding affinities corrected for shifting equilibria during a secondary Ab incubation were consistently closer to the RIA values than the uncorrected affinities. Although the lowest affinity interactions calculated from non-linear reciprocal plots of PA-fgn binding to immobilized fgn were in the range of nonspecific binding in the RIA, it is likely that the use of net A405 eliminated nonspecific associations from consideration in the ELISA. The reciprocal plots were consistently linear for MAb, which would not be expected if contributions from lower affinity nonspecific interactions were present. If ternary complexes of fgn, Ig and albumin do form, albumin may have adsorbed to immobilized fgn, as well as to unoccupied sites on the plastic matrix, during the blocking step, but Tween 20 in the diluent would have precluded nonspecific binding of Ab during subsequent incubations. Any Ab binding to adsorbed albumin would have occurred in background wells and would have been subtracted from the total OD, hence being eliminated from consideration. It is more likely, therefore, that the lower affinity binding seen in non-linear reciprocal plots truly represents lower affinity specific Ab interactions with fgn in PAb preparations.

For PA-fgn and MA-fgn, ΔH° and ΔS° calculated from ELISA data were consistently higher than the values calculated from RIA data, suggesting a greater contribution from hydrophobic interactions in the ELISA. This observation is consistent with numerous reports of decreased immunoreactivity of protein antigens adsorbed to microtiter wells due to partial denaturation on hydrophobic surfaces [50,51]. The microplates used for this study were relatively hydrophobic and molecular rearrangements of fgn during adsorption to the plastic may have exposed apolar residues that would be inaccessible in aqueous solution. The endothermic shift caused by this process was largely offset by the entropic contribution, resulting in a relatively small change in the binding affinity. This study, therefore, demonstrates the suitability of ELISA methodology for molecular characterization of Ab-Ag associations, provided that potential sources of bias are taken into account.

4.2. Binding of Immunoliposomes to Human Fibrinogen and Fibrin

4.2.1. RIA analysis revealed remarkable changes in thermodynamic functions after Ab conjugation to ELIP

Upon conjugation of Ab to ELIP, a striking, consistent increase in ΔH° and ΔS° for both specific and nonspecific interactions of the unconjugated Ab was observed. Ab-Ag association constants remained about the same or decreased by approximately one order of magnitude, resulting from the contribution of changed ΔH° and ΔS° values to ΔG°.

4.2.2. ELISA analysis of additional EGIL preparations indicated variability of binding behavior after conjugation of ELIP to different Abs, but consistency among replicate conjugates of a single Ab

This series of experiments not only permitted comparison of RIA and ELISA data, but also different EGIL lots employing the same Ab, since separate conjugations were performed for RIA and ELISA analyses. For PA-fgn, the RIA-derived affinities of specific interactions were one log higher, and for MA-fgn nearly two logs lower, than association constants calculated from ELISA data, while ΔH° and ΔS° determined by the two methods were similar (dΔH° < 2 kcal/mole, dΔS° < 4 cal/mole°), indicating that relatively small differences in the thermodynamic functions describing the interactions could result in large differences in affinities because of their relative contributions to ΔG°. Based on ELISA data, Ab conjugation to ELIP produced a variety of responses in affinities and thermodynamic functions, ranging from the marked increments of ΔH° and ΔS° observed by RIA analysis (for MAfgn-ELIP) to relatively small differences of the functions (for PAfgn- and MAfb-ELIP). Changes in affinities were within one order of magnitude. It would be expected that the intrinsic affinities measured by ELISA are the same as those determined by RIA, because dissolution of the liposomal membrane by PBS-T following the primary incubation enables the same stoichiometric association of the secondary Ab-AP conjugate with primary Ab as with unconjugated Ab.

4.3. Possible Coupling of Association Energetics to Phospholipid Phase Transitions

Changes in thermodynamic functions following ELIP conjugation of the antibodies studied could have been caused by an interaction between the phospholipid hydrocarbon side chains and possibly denatured fgn domains, but no net free energy decrease would be expected in such an interaction. It is more likely that the observed ΔH° and ΔS° increments represent a connection between the PE gel-liquid crystal phase transition and the Ab-fgn interaction, especially since the characteristic ratio of ΔH° to ΔS° is maintained in every case. A perturbation of PE acyl chain conformation may be driven by the enthalpy of Ab-Ag association, since the correlation of ΔX° vs. percent PET was stronger for ΔH° than for ΔS° and exothermic-endothermic reaction coupling, such as that involving the hydrolysis of high-energy anhydride bonds, occurs often in protein interactions.

Giehl et al. [52], in their differential scanning calorimetric (DSC) study of GM2 activator protein interactions with liposomes, concluded that a Tc decrease caused by nonspecific binding could be attributed to destabilization of the gel phase by perturbations in the head group region of the bilayer transmitted to the hydrocarbon chains. It is well established that allosteric effects, such as hemoglobin cooperativity [53, 54] and RecA protein-induced DNA strand exchange [55], often involve transmission of the favorable ΔG of noncovalent interactions to remote protein sites, where work is performed as mechanical translocation or structural destabilization. This energy transduction effect frequently manifests as changes in the affinity of noncovalent associations.

Although predicted by the deduced energetics of allosteric effects, a triggering of phospholipid phase transitions by noncovalent associations, which reciprocally alter the interaction affinity, may be a somewhat novel observation. In this regard, the covalent PE-Ab linkage, consisting of an α-amino-methylthio-p-maleimidophenylbutyryl moiety having a pronounced π-electronic character, may substantially increase the transduction efficiency between the Ab and the lipid chains. Discrete ionic interactions between Ab and fgn at the site of the Ab epitope are apparently required for transduction to occur, since transduction efficiency correlated well with the ionic character of the interaction and a maximum PE contribution of two moles was seen. Such an occurrence is plausible, considering the likelihood that each fgn molecule subtends (and presumably perturbs) about ten PE head groups and transduction would be expected to involve electron translocations.

It is unlikely, however, that Ab-Ag association provokes PE melting, since the ELIP formulation, which contains egg PC (half oleylated) and cholesterol, is in the liquid crystalline phase throughout the temperature range studied. In addition, we found by DSC analysis that the Tc of MPB-PE is 17° C (Kee, P. and Klegerman, M.E., unpublished data), probably because the bulky head group inhibits acyl chain packing. Furthermore, the thermodynamic function increments observed suggest transmission of PE freezing energetics, which are exothermic, to the Ab binding site. It is possible that transmission of the exothermic Ab-Ag binding enthalpy through PE head groups disrupts van der Waal's contacts between the PE palmitoyl carbons and surrounding acyl chains formed during a putative re-stabilization in the liquid crystalline phase. Transient re-freezing of the PE palmitoyl chains would then be energetically favored at 4-37°C (−1.56 to −0.71 kcal/mole).

Independent testing of the hypothesis that PE gel-liquid crystal phase transitions underlie the thermodynamic characteristics of fgn binding by Afgn-EGIL is problematic. The most direct approach involves microcalorimetric analysis, which permits direct measurement of Ab-Ag association enthalpy increments, as well as association effects on the PE phase transition. The former measurement, employing EGIL at maximum achievable conjugation efficiencies, would yield < 10 μcal, which is below the sensitivity of existing DSC technology. The latter measurement would be even more unfeasible, being in the ncal range. We have verified the unfeasibility of both measurements by DSC analysis (Kee, P. and Klegerman, M.E., unpublished data). DSC analysis utilizing small-molecular model systems appears to be the most promising avenue for testing of the hypothesis and verification of the results found in these studies.

Two alternative hypotheses are suggested by the possibility that Ag binding to Ab-ELIP provokes clustering of Ab-S-PE molecules in the liposomal membrane. On the one hand, a local freezing of acyl chains may be induced, as required by the proposed transduction mechanism; on the other hand, an unfavorable ΔH° may be caused by mutual repulsion of negatively charged head groups (the PE amino function is covalently linked to a sulfur atom), while a positive ΔS° could result from liberation of counterions, with the attendant disordering of water. These hypotheses, dependent upon global liposomal effects, are contradicted, however, by our finding that the characteristic correlations among thermodynamic values are maintained by EGIL interactions in PBS-T (data not shown), suggesting that the relationships reflect intrinsic properties of the Ab-PE conjugate.

4.4. Implications for EGIL Optimization

All Ab-Ag binding characteristics studied for the PA-fgn/fgn interaction were virtually unaffected in the presence of undiluted serum. This remarkable finding not only tends to confirm the robustness of the methodological approach employed, but also indicates that the information derived from it is fully applicable to development of EGIL technology for clinical use.

Rapid clearance of targeted particulates, including immunoliposomes, by the lymphoreticuloendothelial system (LRES) has often been encountered in vivo, resulting in extensive attempts to formulate “stealth” technologies that feature covalent conjugation of polyethylene glycol (PEG) to the particles. Targeting of the stealth micro- and nanoparticles can then be accomplished by coupling antibodies and other ligands to derivatized PEG molecules. Although our EGIL formulation has not been chemically protected from LRES sequestration, we have been able to demonstrate effective targeting in a Yucatan miniswine atherosclerosis model after local administration under clinically relevant conditions [38]. Furthermore, we have demonstrated significant (23-31 percent) enhancement of left ventricular thrombus visualization by epicardial and transthoracic ultrasound imaging in dogs after intravenous administration of PAfgn-ELIP [56]. Thus, full retention of EGIL Ab-Ag binding characteristics in the presence of undiluted normal rabbit serum is entirely consistent with previous observations in vivo using these same EGIL preparations.

The construction of a circulating flow chamber, in which physiologic conditions of constant or pulsatile flow could be simulated [39], has enabled us to assign a quantitative criterion for optimal EGIL fibrin-targeting efficiency (TE). That criterion is eighty percent retention of radiolabeled EGIL on a fibrin-impregnated filter paper disk after 60 minutes at a temperature of 25°C and a shear stress of 15 dyne/cm2. Optimal targeting was observed for PAfgn-EGIL and MAfgn Fab-EGIL, but not for MAfgn-EGIL and PAfgn-EGIL made with half the customary amount of Ab.

Seeking an affinity-dependent parameter that is predictive of optimal TE, we found that the number-dependent avidity, summing all the observed affinities as a product of conjugated Ab number per liposome, which can only be determined by RIA analysis (or other method that permits Scatchard analysis of soluble reactants), correlated well with the flow circuit results (Klegerman, M.E., unpublished data). The avidity threshold for optimal TE was 2 × 1012 M−1 liposome−1. An avidity index that utilizes the maximum information regarding Ag binding obtainable by ELISA analysis, i.e., the sum of all observed affinities expressed as a product of conjugation efficiency (CE), reflecting only specific interactions instead of the actual number of interactions, yielded a much poorer correlation. These results imply that knowing the total ligand concentration available for binding at each Kassoc ([n]) is critical to accurate assessment of TE and that nonspecific interactions contribute significantly to EGIL targeting. It is likely, in fact, that specific interactions between EGIL and fibrin in vivo will be stabilized by nonspecific interactions having affinities only about one order of magnitude less, but occurring at appreciably more numerous sites. Thus, the avidity of nonspecific interactions could equal or exceed that of specific Ag binding.

Even though the underlying mechanisms deduced are presently unsubstantiated, the observed correlations among thermodynamic values permit the prediction of EGIL affinities from the ΔH° and ΔS° of unconjugated Ab binding to Ag. The utility of this approach to EGIL optimization may be limited by large impacts on association constants by relatively small variations about the regression lines, as noted above. The feasibility of this predictive approach will be tested in future studies

4.5. Conclusions

The binding of unconjugated and ELIP-conjugated A-fgn to fgn has been studied by two independent methods, RIA and ELISA. Generally, the binding affinities and thermodynamic functions, ΔH° and ΔS°, calculated from data generated by these methods were in good agreement, with the exception of deviations that could be readily ascribed to known factors. A relatively high-affinity ionic interaction between fgn and Ig, characteristic of these proteins, was detected and elucidated by RIA, but not by ELISA. The correspondence of specific binding characteristics determined by the two methods further served to confirm the results. The nonspecific interactions appeared to increase the likelihood of effective EGIL targeting in vivo, which has been demonstrated in several previous studies. Replication of Ab-Ag binding affinity and thermodynamic characteristics in undiluted normal rabbit serum tends to validate the use of the methodological approach for clinical optimization of EGIL technology. Finally, this study has provided evidence for energy coupling between non-covalent Ab-Ag associations and EGIL phospholipid phase transitions, a phenomenon that may define a new level of immunoliposome utility and control, as well as novel nanotechnological applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by a grant from Mallinckrodt Medical, Inc., and by the National Institutes of Health Grant HL59586. We would like to thank Dr. Robert C. MacDonald for valuable comments and suggestions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Torchilin VP, Khaw BA, Smirnov VN, Haber E. Preservation of antimyosin antibody activity after covalent coupling to liposomes. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1979;89:1114–1119. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(79)92123-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Houck KS, Huang L. The role of multivalency in antibody mediated liposome targeting. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1987;145:1205–1210. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)91565-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maruyama K, Kennel SJ, Huang L. Lipid composition is important for highly efficient target binding and retention of immunoliposomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5744–5748. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen TM, Brandeis E, Hansen CB, Kao GY, Zalipsky S. A new strategy for attachment of antibodies to sterically stabilized liposomes resulting in efficient targeting to cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1237:99–108. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(95)00085-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torchilin VP. Targeting of drugs and drug carriers within the cardiovascular system. Adv Drug Del Rev. 1995;17:75–101. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torchilin VP. Affinity liposomes in vivo: factors influencing target accumulation. J Mol Recog. 1996;9:335–346. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1352(199634/12)9:5/6<335::aid-jmr309>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirpotin D, Park JW, Hong K, Zalipsky S, Li WL, Carter P, Benz CC, Papahadjopoulos D. Sterically stabilized anti-HER2 immunoliposomes: design and targeting to human breast cancer cells in vitro. Biochemistry. 1997;36:66–75. doi: 10.1021/bi962148u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klibanov AL. Antibody-Mediated Targeting of PEG-Coated Liposomes. In: Woodle MC, Storm G, editors. Long-Circulating Liposomes: Old Drugs, New Therapeutics. Landes Biosci; Austin, TX: 1998. pp. 269–286. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bendas G, Krause A, Bakowsky U, Vogel J, Rothe U. Targetability of novel immunoliposomes prepared by a new antibody conjugation technique. Int J Pharmaceutics. 1999;181:79–93. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(99)00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iden DI, Allen TM. In vitro and in vivo comparison of immunoliposomes made by conventional coupling techniques with those made by a new post-insertional approach. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2001;1513:207–216. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(01)00357-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dagar S, Sekosan M, Lee BS, Rubinstein I, Onyuksel H. VIP receptors as molecular targets of breast cancer: implications for targeted imaging and drug delivery. J Controlled Release. 2001;74:129–134. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00326-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dagar S, Krishnadas A, Rubinstein I, Blend MJ, Onyuksel H. VIP grafted sterically stabilized liposomes for targeted imaging of breast cancer: inv vivo studies. J Controlled Release. 2003;91:123–133. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(03)00242-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klibanov AL, Muzykantov VR, Ivanov NN, Torchilin VP. Evaluation of quantitative parameters of the interaction of antibody-bearing liposomes with target antigens. Anal Biochem. 1985;150:251–257. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90507-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson AM, Creeth JE, Jones MN. The specificity and affinity of immunoliposome targeting to oral bacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1369:278–286. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(97)00231-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Makhatadze GI, Privalov PL. Contribution of hydration to protein folding thermodynamics. I. The enthalpy of hydration. J Mol Biol. 1993;232:639–659. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Privalov PL, Makhatadze GI. Contribution of hydration to protein folding thermodynamics. II. The entropy and Gibbs energy of hydration. J Mol Biol. 1993;232:660–679. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baker BM, Murphy KP. Evaluation of linked protonation effects in protein binding reactions using isothermal titration calorimetry. Biophys J. 1996;71:2049–2055. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79403-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oosawa F, Asakura S. Thermodynamics of the Polymerization of Protein. Academic Press; New York: 1975. pp. 56–84. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy KP. Model Compounds and the Interpretation of Protein-Ligand Interactions. In: Ladbury JE, Connelly PR, editors. Structure-Based Drug Design: Thermodynamics, Modeling and Strategy. Springer; New York: 1997. pp. 85–109. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gomez J, Freire E. A Structure-Based Thermodynamic Approach to Molecular Design. In: Ladbury JE, Connelly PR, editors. Structure-Based Drug Design: Thermodynamics, Modeling and Strategy. Springer; New York: 1997. pp. 111–141. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Searle MS, Williams DH, Gerhard U. Partitioning of free energy contributions in the estimation of binding constants: residual motions and consequences for amide-amide hydrogen bond strengths. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:10697–10704. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y, Lipschultz CA, Mohan S, Smith-Gill SJ. Mutations of an epitope hot-spot residue alter rate limiting steps of antigen-antibody protein-protein associations. Biochemistry. 2001;40:2011–2022. doi: 10.1021/bi0014148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore JMR, Patapoff TW, Cromwell MEM. Kinetics and thermodynamics of dimer formation and dissociation for a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody to vascular endothelial growth factor. Biochemistry. 1999;38:13960–13967. doi: 10.1021/bi9905516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu SY, Green WL. Triiodothyronine (T3)-binding immunoglobulins in a euthyroid woman: effects on measurement of T3 (RIA) and on T3 turnover. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1976;42:642–652. doi: 10.1210/jcem-42-4-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Panrucker DE, Lorscheider FL. Radioimmunoassay of rat acute-phase α2-macroglobulin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1982;705:184–191. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(82)90177-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griffiths BW, Godard A. The molecular heterogeneity and instability of radioiodinated human chorionic gonadotrophin. Clin Biochem. 1975;8:400–408. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(75)94154-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roelen CA, de Vries WR, Koppeschaar HP, Vervoorn C, Thijssen JH, Blankenstein MA. Plasma insulin-like growth factor-I and high affinity growth hormone-binding protein levels increase after two weeks of strenuous physical training. Int J Sports Med. 1997;18:238–241. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-972626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuwahara A, Kamada M, Irahara M, Naka O, Yamashita T, Aono T. Autoantibody against testosterone in a woman with hypergonadotropic hypogonadism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:14–16. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.1.4510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oda Y, Sanders J, Roberts S, Maruyama M, Kato R, Perez M, Petersen VB, Wedlock N, Furmaniak J, Rees Smith B. Binding characteristics of antibodies to the TSH receptor. J Mol Endocrinol. 1998;20:233–244. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0200233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Hare T, Rittenberg MB. A simple method for determining KAs of both low and high affinity IgG antibodies. J Immunol Methods. 1998;218:161–167. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cavaco B, Uchigata Y, Porto T, Amparo-Santos M, Sobrinho L, Leite V. Hypoglycaemia due to insulin autoimmune syndrome: report of two cases with characterization of HLA alleles and insulin autoantibodies. Eur J Endocrinol. 2001;145:311–316. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1450311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edgell T, McEvoy F, Webbon P, Gaffney PJ. Monoclonal antibodies to human fibrin: interaction with other animal fibrins. Thromb Haemost. 1996;75:595–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Friguet B, Chaffotte AF, Djavadi-Ohaniance L, Goldberg ME. Measurements of the true affinity constant in solution of antigen-antibody complexes by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Immunol Methods. 1985;77:305–319. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(85)90044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raghava GPS, Agrewala JN. Method for determining the affinity of monoclonal antibody using non-competitive ELISA: a computer program. J Immunoassay. 1994;15:115–128. doi: 10.1080/15321819408013942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Underwood PA. Problems and pitfalls with measurement of antibody affinity using solid phase binding in the ELISA. J Immunol Methods. 1993;164:119–130. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(93)90282-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alkan-Onyuksel H, Demos SM, Lanza GM, Vonesh MJ, Klegerman ME, Kane BJ, Kusczak J, McPherson DD. Development of inherently echogenic liposomes as an ultrasonic contrast agent. J Pharm Sci. 1996;85:486–490. doi: 10.1021/js950407f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Demos SM, Onyuksel H, Gilbert J, Roth SI, Kane B, Jungblut P, Pinto JV, McPherson DD, Klegerman ME. In vitro targeting of antibody-conjugated echogenic liposomes for site-specific ultrasonic image enhancement. J Pharm Sci. 1997;86:167–171. doi: 10.1021/js9603515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Demos SM, Alkan-Onyuksel H, Kane BJ, Ramani K, Nagaraj A, Greene R, Klegerman M, McPherson DD. In vivo targeting of acoustically reflective liposomes for intravascular and transvascular ultrasonic enhancement. J Am Col Cardiol. 1999;33:867–875. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00607-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Demos SM, Dagar S, Klegerman M, Nagaraj A, McPherson DD, Onyuksel H. In vitro targeting of acoustically reflective immunoliposomes to fibrin under various flow conditions. J Drug Target. 1998;5:507–518. doi: 10.3109/10611869808997876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klegerman ME, Hamilton AJ, Huang SL, Tiukinhoy SD, Khan AA, MacDonald RC, McPherson DD. Quantitative immunoblot assay for assessment of liposomal antibody conjugation efficiency. Anal Biochem. 2002;300:46–52. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kricka LJ. Ligand Binder Assays: Labels and Analytical Strategy. M Dekker; New York: 1985. p. p 60. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tiukinhoy-Laing SD, Buchanan K, Parikh D, Huang S, MacDonald RC, McPherson DD, Klegerman ME. Fibrin targeting of tissue plasminogen activator-loaded echogenic liposomes. J Drug Target. doi: 10.1080/10611860601140673. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klotz IM. Numbers of receptor sites from Scatchard graphs: facts and fantasies. Science. 1982;217:1247–1249. doi: 10.1126/science.6287580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eisen HN. Immunology. Harper & Row; New York: 1974. p. p 412. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jones MN. The thermal behaviour of lipid and surfactant systems. In: Jones MN, editor. Biochemical Thermodynamics. 2. Elsevier; New York: 1988. pp. 182–240. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lord ST, Rooney MM, Hopfner KP, Di Cera E. Binding of fibrinogen Aα1-50-β-galactosidase fusion protein to thrombin stabilizes the slow form. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:24790–24793. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.24790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qiu LL, Levinson SS, Keeling KL, Elin RJ. Convenient and effective method for removing fibrinogen from serum specimens before protein electrophoresis. Clin Chem. 2003;49:868–872. doi: 10.1373/49.6.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davey FR, Gordon GB, Boral LI, Gottlieb AJ. Gamma globulin inhibition of fibrin clot formation. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 1976;6:72–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ben-Ami R, Barshtein G, Mardi T, Deutch V, Elkayam O, Yedgar S, Berliner S. A synergistic effect of albumin and fibrinogen on immunoglobulin-induced red blood cell aggregation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:2663–2669. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00128.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suter M, Butler JE. The immunochemistry of sandwich ELISAs. II. A novel system prevents the denaturation of capture antibodies. Immunol Lett. 1986;13:313–316. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(86)90064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Butler JE, Peterman JH, Suter M, Dierks SE. The immunochemistry of solid-phase sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. Federation Proc. 1987;46:2548–2556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Giehl A, Lemm T, Bartelsen O, Sandhoff K, Blume A. Interactiion of the GM2-activator protein with phospholipid-ganglioside bilayer membranes and with monolayers at the air-water interface. Eur J Biochem. 1999;261:650–658. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pettigrew DW, Romeo PH, Tsapis A, Thillet J, Smith ML, Turner BW, Ackers GK. Probing the energetics of proteins through structural perturbation: sites of regulatory energy in human hemoglobin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:1849–1853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.6.1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Englander JJ, Rumbley JN, Englander SW. Signal transmission between subunits in the hemoglobin T-state. J Mol Biol. 1998;284:1707–1716. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kowalczykowski SC, Krupp RA. DNA-strand exchange promoted by RecA protein in the absence of ATP: implications for the mechanism of energy transduction in protein-promoted nucleic acid transactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3478–3482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hamilton A, Huang SL, Warnick D, Stein A, Rabbat M, Madhav T, Kane B, Nagaraj A, Klegerman M, MacDonald R, McPherson D. Left ventricular thrombus enhancement after intravenous injection of echogenic immunoliposomes: studies in a new experimental model. Circulation. 2002;105:2772–2778. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000017500.61563.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.