Abstract

In this paper the effect of uterine artery embolization (UAE) on sexual functioning and body image is investigated in a randomized comparison to hysterectomy for symptomatic uterine fibroids. The EMbolization versus hysterectoMY (EMMY) trial is a randomized controlled study, conducted at 28 Dutch hospitals. Patients were allocated hysterectomy (n = 89) or UAE (n = 88). Two validated questionnaires (the Sexual Activity Questionnaire [SAQ] and the Body Image Scale [BIS]) were completed by all patients at baseline, 6 weeks, and 6, 12, 18, and 24 months after treatment. Repeated measurements on SAQ scores revealed no differences between the groups. There was a trend toward improved sexual function in both groups at 2 years, although this failed to reach statistical significance except for the dimensions discomfort and habit in the UAE arm. Overall quality of sexual life deteriorated in a minority of cases at all time points, with no significant differences between the groups (at 24 months: UAE, 29.3%, versus hysterectomy, 23.5%; p = 0.32). At 24 months the BIS score had improved in both groups compared to baseline, but the change was only significant in the UAE group (p = 0.009). In conclusion, at 24 months no differences in sexuality and body image were observed between the UAE and the hysterectomy group. On average, both after UAE and hysterectomy sexual functioning and body image scores improved, but significantly so only after UAE.

Keywords: Uterine artery embolization, Hysterectomy, Fibroid, Leiomyoma, Sexuality, Body image

Introduction

When hysterectomy looms as a definite treatment for fibroid related menorrhagia, women and their sexual partners often express their concern about negative effects of the operation on their sexual wellbeing [1–4]. Furthermore, the uterus is considered important for a woman’s self-image and sexual image and some women fear that they will be “less of a woman” to their sexual partners [2, 4, 5]. Therefore a hysterectomy may also interfere with the woman’s body image. These concerns may cause some women to choose alternative treatment options [5]. During the last decade, uterine artery embolization (UAE) has emerged as an alternative treatment for hysterectomy [6]. UAE has been investigated in several case series and three randomized controlled trials [7–13], but the advantage of UAE in terms of sexual wellbeing and body image in comparison to hysterectomy remains unknown, since randomized controlled trials on this subject are not available as yet. Randomized controlled data are preferential to nonrandomized data, since nonrandomized data tend to overestimate treatment effect and are prone to selection bias [14]. We initiated a randomized trial comparing UAE and hysterectomy and have published several short-term results previosly [15–17]. In the present paper, we compare changes in sexuality and body image in patients with symptomatic uterine fibroids who were randomly assigned to either UAE or hysterectomy.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

The details of our study design have been described elsewhere and are discussed here briefly [15]. The EMMY trial (EMbolization versus hysterectoMY) is a prospective randomized multicenter clinical trial with 28 participating hospitals in the Netherlands. Eligible patients met the following inclusion criteria: they were clinically diagnosed with uterine fibroids (confirmed by ultrasonography), had menorrhagia as the major complaint, were premenopausal, and had no wish to conceive. All patients were candidates for undergoing a hysterectomy: other treatment options either had failed, were undesired, or had provided unsatisfactory results.

Eligible patients were informed verbally and in writing about possible risks and benefits of both procedures, and were invited to participate in the trial. After written informed consent had been obtained, patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to UAE or hysterectomy by computerized randomization, stratified for hospital. The study was approved by the Dutch Central Committee Involving Human Subjects (www.ccmo.nl) and the local ethics committees of all participating hospitals.

Pre-assessment

All patients were assessed by the attending gynaecologist. Current symptoms and a complete medical and gynaecological history were recorded. All patients underwent a pelvic ultrasound to determine the number of fibroids and the size of the largest fibroid. Sociodemographic characteristics were assessed by means of a questionnaire.

Procedures

Uterine artery embolization

UAE was performed by an interventional radiologist. A catheter was introduced into the femoral artery and advanced over the aortic bifurcation to the contralateral internal iliac artery, and digital subtraction angiography was performed to identify the origin of the uterine artery. When catheters were placed correctly, the UAE was carried out. Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) particles of 355–500 μm were used in all procedures. UAE patients were advised to refrain from sexual intercourse for at least 2 weeks and thereafter, depending on their complaints.

Hysterectomy

The type of hysterectomy and the route of access were determined by the gynecologist. The following procedures were allowed: abdominal hysterectomy, vaginal hysterectomy, laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy, and laparoscopic hysterectomy. Both supravaginal and total hysterectomies were allowed. After discharge hysterectomy patients were advised not to have sex until the first outpatient visit at 6 weeks.

Questionnaires

Sexual functioning and body image were assessed by means of patient questionnaires. At baseline, questionnaires were completed by all patients before randomization. Follow-up questionnaires were completed at 6 weeks and 6, 12, 18, and 24 months after treatment. The questionnaire consisted of the Sexual Activity Questionnaire (SAQ), the Body Image Scale (BIS), and the Mental Component Summary (MCS; as part of the Medical Outcome Study Short Form [MOS SF-36]).

The SAQ, originally designed to investigate sexual functioning in women treated with tamoxifen because of a positive family history of breast cancer [18], is also useful in women with nonmalignant gynecological disorders [19]. In Table 1 the SAQ is displayed. The questionnaire consists of three dimensions, and each dimension yields its own score: pleasure from sexual intercourse (desire, enjoyment, and satisfaction; score range, 0–18), discomfort during intercourse (score range, 0–6), and habit (frequency; score range, 0–3). Pleasure and habit are good with higher scores, while discomfort is worse with higher scores. The SAQ was only filled out by patients who were sexually active during the month before receiving the questionnaire.

Table 1.

The Sexual Activity Questionnaire (SAQ) and the Body Image Scale (BIS)

| SAQ |

| Dimension pleasure |

| 1. Was having sex an important part of your life in the last month? |

| 2. Did you enjoy sexual activity in the last month? |

| 3. Did you desire to have sex with your partner in the last month? |

| 4. In general were you satisfied after sexual activity in the last month? |

| 5. How often did you engage in sexual activity in the last month? |

| 6. Were you satisfied with the frequency of sex in the last month? |

| Dimension discomfort |

| 1. Did you notice dryness of your vagina in the last month? |

| 2. Did you feel pain or discomfort in the last month? |

| Dimension habit |

| 1. How did the frequency of sexual behavior in the last month compare with what is usual for you? |

| BIS |

| In the last month |

| 1. Have you been feeling self-conscious about your appearance? |

| 2. Have you felt less physically attractive as a result of your menstrual bleeding problem? |

| 3. Have you been dissatisfied with your appearance when dressed? |

| 4. Have you been feeling less feminine as a result of your menstrual bleeding problem? |

| 5. Did you find it difficult to look at yourself naked? |

| 6. Have you been feeling less sexually attractive as a result of your menstrual bleeding problem? |

| 7. Did you avoid people because of the way you felt about your appearance? |

| 8. Have you been feeling the treatment has left your body less whole? |

| 9. Have you felt dissatisfied with your body? |

| 10. Have you been dissatisfied with the appearance of your scar? |

Questions on the BIS shown in italics have been omitted

Furthermore, participating patients were asked to judge their current sexual life in two questions: “How would you describe the quality of your current sexual life?” and “How well can you live with your current sexual life?” One of the following responses could be ticked: “very good,” “good,” “moderately good,” “neither good nor bad,” “moderately bad,” “bad,” and “very bad.”

The BIS was designed in order to asses changes in body image among cancer patients [20]. The questionnaire was also found reliable and valid in women with benign gynecological conditions [21]. Table 1 displays the questions of which the BIS consists. Unfortunately, questions 2, 4, and 6 were not represented correctly in the questionnaire due to a translation error. Therefore we decided to omit these questions in order to attain a comparable outcome between groups. The BIS score ranges from 0 to 30. A higher BIS score indicates a worse body image.

In order to assess mental health before treatment as a predictor of worse sexual function after treatment, the MCS score of the 36-item MOS SF-36 was used [22]. This was done because bad preoperative mental health is associated with bad sexual life outcome [23].

Sample Size and Endpoints of the Present Study

The sample size was based on the primary endpoint of the clinical study, published elsewhere [24]: the elimination of menorrhagia in such way that hysterectomy could be avoided in the UAE group in at least 75% of patients within 2 years after the primary interventions.

The objective of the present study was to compare the following endpoints between both interventions: the number of sexually active patients, the scores yielded by the SAQ and the BIS, the subjective quality of sexual life. For this analysis, no separate power calculation was made.

Statistical Analysis

Data entry was performed using SPSS data entry for Windows 3.0. A random sample of 10% of the questionnaires was visually double checked by an independent second investigator, revealing a false entry level of 0.3%. All false data entries were corrected.

All analyses were performed using SPSS (release 11.5.1) statistical software. Missing items in the questionnaire were treated as follows. For the SAQ no advice is available on scoring missing items. If one item was missing, we regarded the dimension score (which the item was part of) as being missing completely, according to earlier research [25]. For the BIS no missing values were allowed since three questions were omitted already. In these cases, the entire score was omitted. For the three omitted questions, the individual mean score of the remaining seven questions was imputed.

First, we determined how many patients in both treatment groups were sexually active before and after treatment. An overall percentage per treatment group was calculated, after which sexual activity in subgroups was assessed: those being sexually active and those not being sexually active before treatment. Second, the mean of the dimension scores were plotted for the hysterectomy and UAE group. Third, the mean differences between all follow-up SAQ dimension scores and baseline were compared between treatment groups. This was only possible for patients who were sexually active both before and after treatment. Within group changes were analyzed as well. Similar analyses were performed for the BIS. Differences in pleasure, discomfort, habit (SAQ), and body image (BIS) between groups over time were tested with repeated measurement analysis, excluding the 6-week measurement for the SAQ, since a high proportion of patients was expected not to be sexually active at that time and therefore not to yield a score. Differences in continuous variables were tested with Student’s t test. Differences in data with skewed distributions were tested with the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test.

The two added questions on the quality of current sexual life were compared between the groups using the chi-square test (or Fishers’ exact test when appropriate). Furthermore, the quality of sex life and the additional questions at the various follow-up moments were compared to baseline, yielding two different options: “worse,” “the same,” or “better” compared to baseline. Differences between the groups were compared with the chi-square test (or Fishers’ exact test when appropriate).

Logistic regression analysis was performed to investigate variables associated with a worse sexual life quality at 24 months after treatment compared to baseline versus unchanged or improved quality of sexual life. First, univariate analysis was performed with the following baseline characteristics: intended treatment, age, BMI, parity, ethnicity, having a partner, employment status, smoking status, number of fibroids, uterine volume measured by ultrasound, dominant fibroid volume measured by ultrasound, existence of any comorbid disease, and mental health status (MCS-MOS-SF36) at baseline. Second, covariates with p values <0.1 in the univariate analysis were selected for multivariate analysis.

All analyses were two-tailed and carried out based on the intention-to-treat principle. A p value <0.05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant.

Results

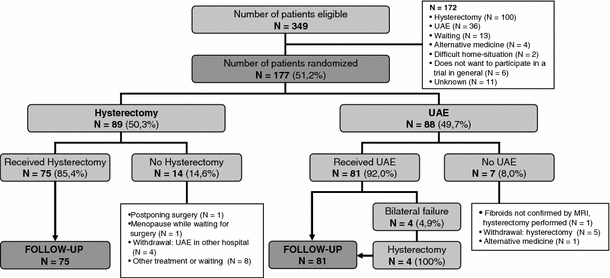

Patients were enrolled between March 2002 and February 2004. Of 349 eligible patients, 177 were randomized: 89 were allocated hysterectomy and 88 were allocated UAE. In the hysterectomy group 14 patients refused the allocated treatment, compared to 7 patients in the UAE group, and these patients withdrew from participation. In 4 UAE patients embolization failed bilaterally. These patients subsequently had a hysterectomy but were analyzed in the UAE group according to the intention-to-treat principle (Fig. 1) [15]. The baseline characteristics of all randomized patients are reported in Table 2. No differences between the groups are apparent, as expected considering the randomized design.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics

| UAE (N = 88) | Hysterectomy (N = 89) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yr), mean (SD) | 44.6 (4.8) | 45.4 (4.2) |

| Body mass index (weight [kg]/length [m]2), mean (SD) | 26.7 (5.6) | 25.4 (4.0) |

| Parity (n) | ||

| 0 | 30 (34.1%) | 20 (22.5%) |

| ≥1 | 58 (65.9%) | 69 (77.5%) |

| Ethnicity (n) | ||

| Black | 24 (27.3%) | 20 (22.5%) |

| White | 54 (61.4%) | 57 (64.0%) |

| Other | 10 (11.4%) | 12 (13.5%) |

| Marital statusa (n) | ||

| Single | 16 (18.2%) | 13 (14.8%) |

| Married | 55 (62.5%) | 54 (61.4%) |

| Living apart together | 5 (5.7%) | 4 (4.5%) |

| Divorced | 12 (13.6%) | 15 (17.0%) |

| Widow | 0 (0%) | 2 (2.3%) |

| Partner relationshipa (n) | ||

| No partner | 13 (15.3%) | 19 (22.4%) |

| Partner | 72 (84.7%) | 66 (77.6%) |

| Employment statusa (n) | ||

| Employed | 68 (77.3%) | 69 (78.4%) |

| Unemployed | 20 (22.7%) | 19 (21.6%) |

| Smoking status (n) | ||

| Current smoker | 21 (23.9%) | 23 (25.8%) |

| Former smoker | 11 (12.5%) | 14 (15.7%) |

| Nonsmoker | 56 (63.6%) | 52 (58.4%) |

| Comorbid diseaseb | ||

| Any comorbid disease | 24 (27.3%) | 22 (24.7%) |

| Number of fibroids, median (range) | 2 (1–20) | 2 (1–9) |

| Uterine volume (cm3), median (range) | 321 (31–3005) | 313 (58–3617) |

| Fibroid volume (dominant fibroid; cm3), median (range) | 59 (1–673) | 87 (4–1641) |

| Mental Component Summary (SF-36), mean (SD) | 40.9 (10.7) | 41.5 (11.0) |

aSome values are missing

bAny of the following: hypertension, diabetes, astma, clotting disease, system disease, or other

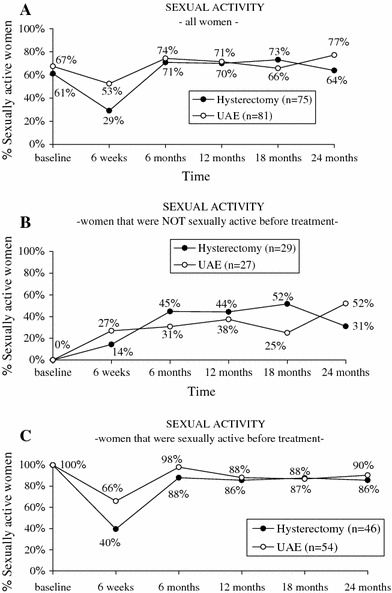

The proportion of questionnaires available for analysis ranged from 96.0% (baseline) to 98.7% (6 weeks, 24 months). Before treatment 54 of 81 (67%) and 46 of 75 (61%) of the participating patients were sexually active in the UAE and hysterectomy groups, respectively (Fig. 2A). Six weeks after treatment, sexual activity had decreased in both groups, with significantly more patients showing sexual activity in the UAE group compared to hysterectomy (53% versus 29%; p = 0.004). Hereafter sexual activity was restored in both groups, with no significant differences between the groups at 24 months (p = 0.07).

Fig. 2.

Proportion of sexually active women, by treatment strategy, over time. (A) The weighted average of women who were not sexually active at baseline (B) and those who were sexually active at baseline (C)

Patients who were not sexually active before treatment gradually resumed sexual activity after both UAE and hysterectomy (Fig. 2B). After 24 months 31% (hysterectomy) and 52% (UAE) were sexually active (p = 0.118). No significant differences were observed between the groups.

Among those patients who were sexually active before treatment, there was a major drop in activity at 6 weeks after treatment, which was partially restored. After 2 years, 86% (UAE) and 90% (hysterectomy) of these patients had resumed their sexual activities (Fig. 2C). Only at 6 weeks had significantly more UAE patients resumed sexual activity (p = 0.01).

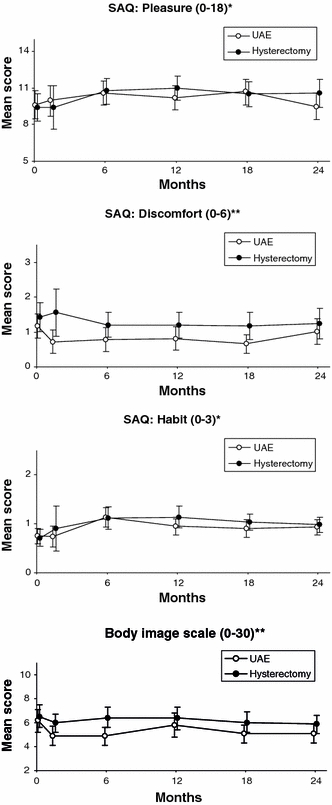

Figure 3 shows the course of the SAQ dimensions pleasure, discomfort, and habit and the BIS scores over time. There were no differences between the groups at baseline (pleasure, p = 0.76; discomfort, p = 0.44; habit, p = 0.77; body image,: p = 0.60). Repeated measurements revealed no differences between the groups for the SAQ dimensions pleasure (p = 0.343), discomfort (p = 0.246), and habit (p = 0.453) or for body image scores (p = 0.359). Table 3 shows the changes in dimension scores per treatment group for patients who were sexually active at baseline. Positive numbers for pleasure and habit and negative numbers for discomfort and body image are indicative for improvement compared to baseline. No significant differences were found between the two treatment groups at all time points, except for body image at 6 months after treatment: body image had improved significantly more in UAE patients than in hysterectomy patients (UAE, –1.34, versus hysterectomy, no change; difference, –1.34; 95% CI, –2.50 to –0.18; p = 0.02). Within the groups, however, a significant improvement of various dimension scores was noted (indicated in boldface): at 24 months UAE patients reported significantly less discomfort, a higher frequency of intercourse, and a better body image compared to baseline (p = 0.022, p = 0.022, and p = 0.009 respectively). At 24 months hysterectomy patients improved on all dimensions compared to baseline, but differences were not statistically significant.

Fig. 3.

Pleasure, discomfort, habit, and body image, by treatment strategy, over time

Table 3.

Mean differences in pleasure, discomfort, habit, and body image compared to baseline, by treatment strategy, over time

| UAE | Hysterectomy | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SAQ: pleasure (0–18)a | |||

| 6 wk | 0.29 | −0.50 | 0.47 |

| 6 mo | 1.63 | 1.23 | 0.61 |

| 12 mo | 0.95 | 1.49 | 0.50 |

| 18 mo | 1.86 | 0.68 | 0.13 |

| 24 mo | 0.89 | 1.18 | 0.74 |

| SAQ: discomfort (0–6)b | |||

| 6 wk | −0.25 | −0.21 | 0.96 |

| 6 mo | −0.58 | −0.32 | 0.41 |

| 12 mo | −0.47 | −0.47 | 0.98 |

| 18 mo | −0.51 | −0.29 | 0.51 |

| 24 mo | −0.43 | −0.49 | 0.88 |

| SAQ: habit (0–3)a | |||

| 6 wk | −0.03 | 0.00 | 0.92 |

| 6 mo | 0.48 | 0.28 | 0.30 |

| 12 mo | 0.18 | 0.42 | 0.24 |

| 18 mo | 0.27 | 0.19 | 0.70 |

| 24 mo | 0.28 | 0.22 | 0.74 |

| BIS (0–30)b | |||

| 6 wk | −1.27 | −0.28 | 0.10 |

| 6 mo | −1.34 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| 12 mo | −0.24 | 0.08 | 0.64 |

| 18 mo | −1.24 | –0.28 | 0.15 |

| 24 mo | −1.06 | –0.50 | 0.36 |

Note. SAQ, Sexual Activity Questionnaire; BIS, Body Image Scale. Boldface numbers indicate a significant difference from baseline within group (p < 0.05)

aA higher score represents more favorable sexual functioning (pleasure, habit)

bA lower score represents more favorable sexual functioning (discomfort) or body image

Table 4 reports the patients’ experienced quality of their sexual life at 6 weeks and 12 and 24 months. No differences between groups were observed. Table 5 presents the proportion of patients who judged the quality of sexual life as better, comparable to, or worse compared to baseline based on the question: “How is the quality of your current sexual life?” A minority of patients reported worsened sexual life quality compared to baseline at all time points. At 24 months the proportion of patients reporting a worse sexual life compared to baseline was slightly higher in the UAE than in the hysterectomy group, but the difference was not statistically significant (29.3% versus 23.5%; p = 0.43).

Table 4.

Satisfaction with sexual life and ability to cope with sexual life, by treatment strategy, over time

| Baseline | 6 weeks | 12 months | 24 months | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UAE (N = 81) | Hyst. (N = 75) | p value | UAE (N = 81) | Hyst. (N = 75) | p value | UAE (N = 81) | Hyst. (N = 75) | p value | UAE (N = 81) | Hyst. (N = 75) | p value | |

| How is the quality of your current sex life? | ||||||||||||

| Very good | 15 | 8 | 0.84 | 7 | 1 | 0.48 | 7 | 11 | 0.35 | 8 | 11 | 0.54 |

| Good | 22 | 27 | 25 | 22 | 31 | 18 | 29 | 21 | ||||

| Somewhat good | 15 | 13 | 12 | 13 | 9 | 11 | 8 | 12 | ||||

| Neither good nor bad | 12 | 12 | 23 | 19 | 15 | 21 | 16 | 15 | ||||

| Somewhat bad | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 8 | 8 | ||||

| Bad | 4 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||||

| Very bad | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 1 | ||||

| How well can you live with your current sex life? | ||||||||||||

| Very good | 9 | 3 | 0.77 | 11 | 6 | 0.33 | 18 | 17 | 0.93 | 20 | 17 | 0.78 |

| Good | 20 | 21 | 37 | 30 | 35 | 30 | 34 | 31 | ||||

| Somewhat good | 10 | 12 | 15 | 16 | 11 | 13 | 10 | 11 | ||||

| Neither good nor bad | 20 | 17 | 10 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 10 | 6 | ||||

| Somewhat bad | 8 | 9 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 5 | ||||

| Bad | 4 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Very bad | 6 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||

Table 5.

Changes in sexual wellbeing compared to baseline, by treatment strategy, over time

| UAE (n = 81) | Hysterectomy (n = 75) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 months | |||

| Worse | 16 | 13 | 0.68 |

| The same | 25 | 27 | |

| Improved | 32 | 25 | |

| 12 months | |||

| Worse | 17 | 14 | 0.81 |

| The same | 29 | 26 | |

| Improved | 25 | 27 | |

| 24 months | |||

| Worse | 22 | 16 | 0.32 |

| The same | 27 | 20 | |

| Improved | 26 | 32 | |

Univariate logistic regression analysis revealed BMI, number of fibroids, and presence of comorbid disease to be associated with a worsened quality of sexual life at 24 months compared to baseline (p < 0.1). Allocated treatment and mental health at baseline were not associated with worse outcome.

BMI was not significant in the multivariate analysis (p = 0.163). The other two parameters remained significantly associated with worse outcome: a higher number of fibroids (OR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.51–0.94; p = 0.018) predicted a decreased risk of a worsening sexual life at 24 months compared to baseline, while the presence of comorbid disease (OR, 3.20; 95% CI, 1.38–7.41; p = 0.007) was associated with an increased risk of a worse sexual life quality at 24 months after treatment compared to baseline.

Discussion

In our trial no differences, on average, in sexual function at 24 months were observed between UAE and hysterectomy. After both treatments the dimensions “pleasure” and “habit” improved, while the dimension “discomfort” decreased at 24 months compared to baseline, although only the UAE group showed significant improvement in discomfort and frequency of intercourse.

Sexuality and body image after UAE have never been evaluated in a randomized controlled trial before. However, some nonrandomized series have addressed this subject. The improvement of sexual functioning after UAE was in accordance with the limited number of earlier studies on this subject [26–28], which reported a significant improvement in sexual functioning as well. Sexual functioning after hysterectomy has received much attention in the literature. Improvement in sexual functioning after hysterectomy might indirectly be associated with the consequences of surgery, such as less worry about unwanted pregnancy, absence of vaginal bleeding, and more time for sexual activities by the cessation of monthly periods [29]. Most reports on sexual functioning after hysterectomy found significant benefits in various aspects of sexual functioning [25, 30–35]. In contrast, the improvement in sexual functioning within our hysterectomy group at 24 months of follow-up was not statistically significant in our trial. This might be explained by insufficient power, which is partly due to the relatively small sample size for the SAQ scores in our population: change scores were only available from women who were sexually active at baseline and at follow-up. Furthermore, the studies on sexuality after hysterectomy used varying follow-up intervals, ranging from 6 months to 2 years. In our series, hysterectomy patients experienced significantly improved pleasure and habit scores at 12 months of follow-up. These results might indicate that improvement in sexual functioning after hysterectomy could be temporary. On the other hand, a review article recently suggested that there is no scientific proof for either improvement or deterioration of sexual functioning after hysterectomy, unless hysterectomy was performed based on a sound clinical indication [29]. In our patient group, however, there was no doubt about the indication: complaints were serious and lengthy enough to warrant a hysterectomy.

Although, on average, SAQ scores for the group as a whole improved, there was a small group of women who reported a deterioration in self-reported quality of sexual life, consistent with other reports [30–32, 34, 36]. For obvious reasons, the prospects of deterioration of sexual life might be of greater concern to patients than the improvement after treatment. Regression analysis of worsened sexual life revealed that women with a low number of fibroids (possibly representing a group of women with less severe complaints) and women with other concomitant chronic diseases might not benefit from fibroid treatment in terms of sexual life improvement.

The improved body image after UAE in our series is in accordance with another study that reported higher self-consciousness after UAE [26]. After hysterectomy a period of temporary worsened body image following the operation has been described previously [25, 36, 37]. This was not confirmed by our results, but in accordance with these studies, a normal or even improved body image was found 1 year after hysterectomy.

There are several limitations of our study that need to be addressed. First, the values of the SAQ dimensions were based on all sexual active women at the various points in time. Reported values may reflect an ever-changing group of sexually active women. At any stage, some women may cease while others may initiate sexual activity. Of all non-sexually active women before treatment, 50% became active after treatment. When comparing pre- and posttreatment scores, these women cannot be included, since their baseline scores were missing.

Second, the significant difference between resumption of sexual activity between the groups at 6 weeks is probably explained by differences in counseling between both treatments as mentioned earlier: hysterectomy patients in our trial were told not to have sex until the first outpatient visit at 6 weeks, while UAE patients were advised to refrain from intercourse for at least 2 weeks and thereafter, depending on their complaints.

Third, we allowed all kinds of hysterectomies, thereby possibly biasing the results in the hysterectomy group. However, various reports found no long-term differences in sexual functioning after various surgical routes of hysterectomy [25, 32, 35].

Finally, as described above, three questions on the BIS were omitted because of wrongly posed questions, thereby creating asymmetry in the treatment arms. Since the remaining questions in both groups were identical, the comparison between the groups is still valid but reduces the comparability with other series.

In conclusion, at 24 months no differences in sexuality and body image were observed between the UAE and the hysterectomy groups. After both UAE and hysterectomy, on average, sexual functioning and body image scores improved, but significantly so only after UAE.

Acknowledgments

The EMMY study is funded by ZonMw “Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development” (grant application no. 945-01-017) and supported by Boston Scientific Corporation, The Netherlands. We would like to thank all participating patients, EMMY-trial group members, nurses, and other contributors who made the trial possible. We thank M. Nuberg, H. van Welsum, and M. Cornet for their administrative efforts. The EMMY-trial participants and hospitals are as follows: J. Reekers, W. Ankum, M. Burger, G. Bonsel, Erwin Birnie, W. Hehenkamp, N. Volkers (Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam); S. de Blok, C. de Vries (Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis, Amsterdam); T. Salemans, G. Veldhuyzen van Zanten (Atrium Medical Centre, Heerlen); D. Tinga, T. Prins (Groningen University Hospital, Groningen); P. Sleyvers, M. Rutten (Bosch Medical Centre, Den Bosch); M. Smeets, N. Aarts (Bronovo Hospital, The Hague); P. van der Moer, D. Vroegindeweij (Medical Centre Rijnmond-Zuid, Rotterdam); F. Boekkooi, L. Lampmann (St. Elisabeth Hospital, Tilburg); G. Kleiverda, (Flevo Hospital, Almere); R. Dik, J. Marsman (Gooi-Noord Hospital, Laren); C. de Nooijer, I. Hendriks, G. Guit (Kennemer Gasthuis, Haarlem); H. Ottervanger, H. van Overhagen, (Leyenburg Hospital, The Hague); A. Thurkow (St. Lucas/Andreas Hospital, Amsterdam); P. Donderwinkel, C. Holt (Martini Hospital, Groningen); A. Adriaanse, J. Wallis, (Medical Center Alkmaar, Alkmaar); J. Hirdes, J. Schutte, W. de Rhoter (Medical Center Leeuwarden, Leeuwarden); P. Paaymans, R. Schepers-Bok (Hospital Midden-Twente, Hengelo); G. van Doorn, J. Krabbe, A. Huisman, (Medisch Spectrum Twente, Enschede); M. Hermans, R. Dallinga (Reinier de Graaf Gasthuis, Delft); F. Reijnders, J. Spithoven, (Slingeland Hospital, Doetichem); W. de Jager, P. Veekmans, (St. Jans Gasthuis, Weert); P. van der Heijden, M. Veereschild, J. van den Hout, (Twenteborg Hospital, Almelo); I. van Seumeren, A. Heinz, R. Lo, W. Mali (University Hospital Utrecht, Utrecht); J. Lind, Th. de Rooy (Westeinde Hospital, The Hague); M. Bulstra, F. Sanders (Diakonessenhuis Utrecht, Utrecht); J. Doornbos (De Heel Hospital, Zaandam); P. Dijkhuizen, M. van Kints (Rijnstate Hospital, Arnhem); Ph. Engelen, R. Heijboer (Slotervaart Hospital, Amsterdam).

Footnotes

Trial registration: www.clinicaltrials.com (identifier: NCT00100191). All centers where the trial was conducted, other than those below, are listed in the Acknowledgments.

References

- 1.Dennerstein L, Wood C, Burrows GD (1977) Sexual response following hysterectomy and oophorecomy. Obstet Gynecol 49(1):92–96 [PubMed]

- 2.Richter DL, McKeown RE, Corwin SJ, et al. (2000) The role of male partners in women’s decision making regarding hysterectomy. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 9(Suppl 2):S51–S61 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Bernhard LA (1992) Men’s views about hysterectomies and women who have them. Image J Nurs Sch 24(3):177–181 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Groff JY, Mullen PD, Byrd T, et al. (2000) Decision making, beliefs, and attitudes toward hysterectomy: a focus group study with medically underserved women in Texas. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 9(Suppl 2):S39–S50 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Nevadunsky NS, Bachmann GA, Nosher J, et al. (2001) Women’s decision-making determinants in choosing uterine artery embolization for symptomatic fibroids. J Reprod Med 46(10):870–874 [PubMed]

- 6.Ravina JH, Herbreteau D, Ciraru-Vigneron N, et al. (1995) Arterial embolisation to treat uterine myomata. Lancet 346(8976):671–672 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Pron G, Bennett J, Common A, et al. (2003) The Ontario Uterine Fibroid Embolization Trial. Part 2. Uterine fibroid reduction and symptom relief after uterine artery embolization for fibroids. Fertil Steril 79(1):120–127 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Walker WJ, Pelage JP (2002) Uterine artery embolisation for symptomatic fibroids: clinical results in 400 women with imaging follow up. BJOG 109(11):1262–1272 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.McLucas B, Adler L, Perrella R (2001) Uterine fibroid embolization: nonsurgical treatment for symptomatic fibroids. J Am Coll Surg 192(1):95–105 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Spies JB, Ascher SA, Roth AR, et al. (2001) Uterine artery embolization for leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol 98(1):29–34 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Pinto I, Chimeno P, Romo A, et al. (2003) Uterine fibroids: uterine artery embolization versus abdominal hysterectomy for treatment. A prospective, randomized, and controlled clinical trial. Radiology 226(2):425–431 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Edwards RD, Moss JG, Lumsden MA, et al. (2007) Uterine-artery embolization versus surgery for symptomatic uterine fibroids. N Engl J Med 356(4):360–370 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Mara M, Fucikova Z, Maskova J, et al. (2006) Uterine fibroid embolization versus myomectomy in women wishing to preserve fertility: preliminary results of a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 126(2):226-233 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Kunz R, Oxman AD (1998) The unpredictability paradox: review of empirical comparisons of randomised and non-randomised clinical trials. BMJ 317(7167):1185–1190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Hehenkamp WJ, Volkers NA, Donderwinkel PF, et al. (2005) Uterine artery embolization versus hysterectomy in the treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids (EMMY trial): peri- and postprocedural results from a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 193(5):1618–1629 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Hehenkamp WJ, Volkers NA, Birnie E, et al. (2006) Pain and return to daily activities after uterine artery embolization and hysterectomy in the treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids: results from the randomized EMMY trial. Cardiovasc Interv Radiol 29(2):179–187 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Volkers NA, Hehenkamp WJ, Birnie E, et al. (2006) Uterine Artery Embolization in the Treatment of Symptomatic Uterine Fibroid Tumors (EMMY trial): periprocedural results and complications. J Vasc Interv Radiol 17(3):471–480 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Thirlaway K, Fallowfield L, Cuzick J (1996) The sexual activity questionnaire: a measure of women’s sexual functioning. Quality Life Res 5(1):81–90 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Stead ML, Crocombe WD, Fallowfield LJ, et al. (1999) Sexual activity questionnaires in clinical trials: acceptability to patients with gynaecological disorders. BJOG 106(1):50–54 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Hopwood P, Fletcher I, Lee A, et al. (2001) A body image scale for use with cancer patients. Eur J Cancer 37(2):189–197 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Stead ML, Fountain J, Napp V, et al. (2004) Psychometric properties of the Body Image Scale in women with benign gynaecological conditions. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 114(2):215–220 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Ware JE Jr (2000) SF-36 health survey update. Spine 25(24):3130–3139 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Hartmann KE, Ma C, Lamvu GM, et al. (2004) Quality of life and sexual function after hysterectomy in women with preoperative pain and depression. Obstetr Gynecol 104(4):701–709 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Volkers NA, Hehenkamp WJ, Birnie E, Ankum WM, Reekers JA (2007) Uterine artery embolization versus hysterectomy in the treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids: two-years’ outcome from the randomized EMMY trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 196(6):519.e1–519.e11 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Garry R, Fountain J, Brown J, et al. (2004) EVALUATE hysterectomy trial: a multicentre randomised trial comparing abdominal, vaginal and laparoscopic methods of hysterectomy. Health Technol Assess 8(26):1–154 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Smith WJ, Upton E, Shuster EJ, et al. (2004) Patient satisfaction and disease specific quality of life after uterine artery embolization. Am J Obstetr Gynecol 190(6):1697–1703 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Scheurig C, Gauruder-Burmester A, Kluner C, et al. (2006) Uterine artery embolization for symptomatic fibroids: short-term versus mid-term changes in disease-specific symptoms, quality of life and magnetic resonance imaging results. Hum Reprod 21(12):3270–3277 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Goodwin SC, Bradley LD, Lipman JC, et al. (2006) Uterine artery embolization versus myomectomy: a multicenter comparative study. Fertil Steril 85(1):14–21 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Maas CP, Weijenborg PT, ter Kuile MM (2003) The effect of hysterectomy on sexual functioning. Annu Rev Sex Res 14:83–113 [PubMed]

- 30.Rhodes JC, Kjerulff KH, Langenberg PW, et al. (1999) Hysterectomy and sexual functioning. JAMA 282(20):1934–1941 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Helstrom L, Sorbom D, Backstrom T (1995) Influence of partner relationship on sexuality after subtotal hysterectomy. Acta Obstetr Gynecol Scand 74(2):142–146 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Roovers JPWR, van der Bom JG, van der Vaart CH, et al. (2003) Hysterectomy and sexual wellbeing: prospective observational study of vaginal hysterectomy, subtotal abdominal hysterectomy, and total abdominal hysterectomy. BMJ 327(7418):774–777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Kuppermann M, Varner RE, Summitt RL, et al. (2004) Effect of hysterectomy vs medical treatment on health-related quality of life and sexual functioning—the medicine or surgery (Ms) randomized trial. JAMA 291(12):1447–1455 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Dragisic KG, Milad MP (2004) Sexual functioning and patient expectations of sexual functioning after hysterectomy. Am J Obstetr Gynecol 190(5):1416–1418 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Long CY, Fang JH, Chen WC, et al. (2002) Comparison of total laparoscopic hysterectomy and laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy. Gynecol Obstetr Invest 53(4):214–219 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Roussis NP, Waltrous L, Kerr A, et al. (2004) Sexual response in the patient after hysterectomy: total abdominal versus supracervical versus vaginal procedure. Am J Obstetr Gynecol 190(5):1427–1428 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Schonefuss G, Hawighorst-Knapstein S, Trautmann K, et al. (2001) [Body image in gynecologic patients before and after radical surgery]. Zentralbl Gynakol 123(1):23–26 [DOI] [PubMed]