Abstract

Objective

To find out if administration of melatonin facilitates discontinuation of benzodiazepine (BD) therapy in patients with insomnia.

Method

A placebo controlled trial in nine general practices in the Netherlands. Long-term users of benzodiazepines were asked by their GP to participate in a discontinuation program in combination with melatonin or placebo. The intervention and follow-up period lasted one year. During this period participants received four questionnaires about their use of sleeping medication and several health instruments. The urine of all participants was tested for the presence of benzodiazepines, as proof of the discontinuation.

Main outcome measure

The discontinuation of benzodiazepine use measured by questionnaires and urine samples at three assessment points.

Results

A total of 503 long-term users were selected by the GPs, of whom 38 patients (16M/22F) participated. After one year 40% had stopped their benzodiazepine use, both in the intervention group on melatonin and in the placebo control group. Comparing stoppers and non-stoppers did not reveal significant differences in benzodiazepine use, or awareness of problematic use.

Conclusion

Our findings do not conclusively indicate that melatonin is helpful for the discontinuation of the use of benzodiazepines, but the average dose of benzodiazepines in the group was low. Further investigation is necessary, with special attention to the possible influence of the daily dose on the facilitation effect of melatonin.

Keywords: Discontinuation, Hypnotics, Long-term benzodiazepine use, Melatonin, Primary care, The Netherlands

Impact of findings on practice

stopping long-term use of benzodiazepine hypnotics is difficult

users of a high daily dose might be more responsive to the effect of melatonin on the discontinuation of benzodiazepines

investigators should take into account the difficulty of recruiting patients for studies on discontinuing the use of benzodiazepines

Introduction

The point prevalence of the use of sleeping medication, often benzodiazepines (BD), in countries such as the Netherlands is approximately 6% [1], with over one-third being long-term users. This does not meet the standard of the Dutch Society of General Practitioners, which advises that hypnotics should not be prescribed longer than for a period of 10 days [2]. After a minimal intervention strategy such as sending an educational letter, one in every four users stops [3–5]. As an aid to discontinuation, several treatments have been used, e.g., certain drugs [6] and cognitive therapy [7], without added value.

The circadian rhythm in humans is controlled by the endogenous biological clock, located in the suprachiasmatic nuclei of the hypothalamus and influenced by light and darkness to the body [8]. Suprachiasmatic projections regulate the pineal gland and its production of melatonin. The primary physiological function of melatonin is to convey information about the daily cycle of light and darkness to the body’s physiology. Melatonin production changes with age and is lower in the elderly. Its secretion is high during the night and has an effect on falling asleep. There is evidence that low doses of melatonin improve initial sleep quality in selected elderly insomniacs [9]. Some BDs have shown to have a negative effect on melatonin production in the pineal gland [8].

Garfinkel et al. [10] investigated stopping the chronic use of BD sleeping medication with the help of melatonin (5 mg). In their randomized discontinuation trial melatonin appeared efficacious: 14 of 18 (78%) patients on melatonin stopped their BD compared to 4 out of 16 (25%) in a placebo control group.

A study in elderly patients of Cardinali et al. [11] does not support efficacy of melatonin to reduce the use of benzodiazepines in low doses. Forty-five patients were randomized to receive either melatonin (3 mg) or placebo for six weeks. In two steps BD was tapered off and stopped after four weeks. Several sleep parameters were assessed and found not to be different for both groups.

The administration of melatonin as a sleeping medication is a contradictory tool to help people discontinue use of BDs.

Aim of the study. The main research question in our trial was whether melatonin is helpful in discontinuing the use of BD sleeping medication, looking at the stopping rate. Secondary objectives are finding the possible influence of other variables on stopping, such as age, gender, period of BD use, and dependence on BD. Besides, we investigated a putative shift of addiction, e.g., to alcohol or smoking.

Method

Our study was designed as a randomized placebo-controlled discontinuation trial. We gathered data in nine general practices (2001–2004). The patients, their GPs and the principal investigator were blinded for the study medication. All practices were located in Maastricht, in the south of the Netherlands.

Included are adult patients who used BD as a sleeping medication for more than three months (defined as long-term use) with a minimum use of three days per week. Patients were selected via their GPs, in six practices through the desk prescriptions, in two on the basis of a pharmacy print out, and in one through the problem list in the medical file on the ICPC-code P17 (drug addiction) [12]. Exclusion criteria were the use of more than one BD at the same time, use of another type of sleep medication, use of stimulants and, according to their GP, alcohol misuse, serious mental/somatic disease or unfit to participate.

All patients who were selected received an invitation letter from their GP that also informed them of the disadvantages of long-term use of BD. A short questionnaire was added to check the inclusion criteria. All respondents meeting the inclusion criteria received by mail a questionnaire (T0): about the use of sleeping medication, sleep complaints (SWEL) [13], sleep quality [14], general health experience (RAND-36) [15], BD dependence (Bendep-SRQ) [16] and habit formation (amount of alcoholic consumptions and/or cigarettes/cigars per day). The sleep wake experience list (SWEL) is a validated instrument to study chronic sleep complaints (insomnia, hypersomnia or the combination of those two). The benzodiazepine dependence self-report questionnaire (Bendep-SRQ) is a validated instrument to measure BD dependency, scoring in subscales the degree of awareness of problematic BD use, degree of preoccupation with respect to the availability of BDs, degree of lack of compliance with the therapeutic BD regimen, and the degree of unambiguity of experienced BD withdrawal (Bendep-SRQ, scale 4)

At the end of the questionnaire, we asked specifically whether the patient was willing to discontinue use of BDs. Participants had to send back an informed consent form. All participants were checked for liver and kidney function and their urine was tested for BD with a fluorescence polarization immunoassay (FPIA) [17].

After returning the informed consent, patients were included for random allocation.

The use of sleeping medication at the start of the study was compared with the defined daily dose (DDD) of the patient’s hypnotic. It was expressed as a quotient of prescribed daily dose (PDD) relative to the defined daily dose, i.e., PDD/DDD. The PDD was based on the completed questionnaire (T0). We created three categories using this quotient: low (quotient ≤ 0.5), average (0.5 < quotient < 1.0) and high use (quotient ≥ 1.0).

All participants received a stopping scheme of their BD via their own pharmacy. Their BD was converted to an equivalent dose of diazepam [18] that was stabilized for two weeks and then further converted every two weeks to 75%, 50%, 25%, 12.5% and 0% of the original dose. We added 5 mg melatonin or placebo which had to be taken 4 h before patients went to bed. After stopping BD we continued the use of melatonin or placebo for six more weeks. Furthermore a questionnaire was sent at 18 weeks (T1), 26 weeks (T2) and 52 weeks (T3) after the beginning of the discontinuation. All questionnaires contained the same set of instruments. Also urine samples for BD determination were required at T1 and T3.

Results

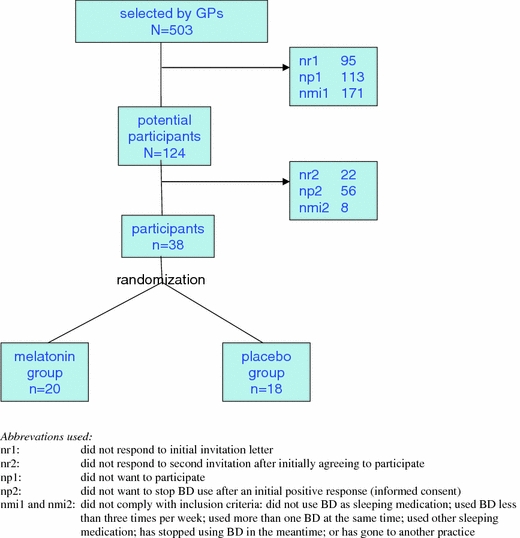

The GPs selected 503 patients for our trial, 138 males and 365 females. Of these, 80% responded to our invitation letter (Fig. 1). Six patients reported to have stopped their use of sleeping medication already. Sixteen patients used two or more BDs, and were excluded from the study. Of all responders, 124 appeared to be willing to participate.

Fig. 1.

Selection of patients and response/non-response; participants

Receiving the first questionnaire of these 124 patients, 22 did not respond, 56 decided not to participate and eight patients did not meet the inclusion criteria (six of whom had already stopped the BD use). At the end, only 38 participants (16 males and 22 females) were indicated to take part in the study. They were randomly allocated to melatonin or placebo.

The participants compared to the non-participants were more often males (40% vs. 25%), and had a lower age (<50 years, 16% vs. 5%) and less elderly (>80 years, 5% vs. 18%). Of the total group, 76% were 60 years or older.

The characteristics of all participants are listed in Table 1. No differences were found between the melatonin and the placebo group. The sleep quality was rated bad in 58% of the cases. According to the SWEL 10 of the 38 participants reported that they did not have any sleeping complaints (any more) Of the other 28, 18 complained of insomnia, three of hypersomnia, and seven of a combination of both. Most participants (76%) used a low dose of BD (PDD/DDD < 1.0). According to the score on the Bendep-SRQ list, 61% of the participants were aware that they had problematic BD use.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 38 participants, and for melatonin and placebo separately

| Melatonin group n = 20 numbers (%) | Placebo group n = 18 numbers (%) | Total participants n = 38 numbers (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 6 (30) | 10 (56) | 16 (42) |

| Female | 14 (70) | 8 (44) | 22 (58) | |

| Age in years | <50 | 3 (15) | 3 (17) | 6 (16) |

| 50–59 | 3 (15) | 3 (17) | 6 (16) | |

| 60–69 | 6 (30) | 7 (39) | 13 (34) | |

| 70−79 | 7 (35) | 4 (22) | 11 (29) | |

| ≥80 | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 2 (5) | |

| Health insurance | National health insurance | 16 (80) | 18 (100) | 34 (90) |

| Private insurance | 4 (20) | – | 4 (10) | |

| Sleep quality | Good | 7 (35) | 5 (28) | 12 (32) |

| Bad | 11 (55) | 11 (61) | 22 (58) | |

| 2 missing | 2 missing | 4 missing | ||

| Period of use of BD | <1 year | – | – | – |

| 1−5 years | 7 (35) | 7 (39) | 14 (37) | |

| 6−9 years | 4 (20) | 4 (22) | 8 (21) | |

| ≥10 years | 9 (45) | 6 (34) | 15 (39) | |

| 1 missing | 1 missing | |||

| Daily use of BD (PDD/DDD) | ≤0.5 (low) | 11 (55) | 14 (78) | 25 (66) |

| 0.5–1.0 (moderate) | 4 (20) | – | 4 (10) | |

| ≥1.0 (high) | 5 (25) | 4 (22) | 9 (24) | |

| Smoking | Yes | 9 (45) | 7 (39) | 16 (42) |

| No | 10 (50) | 11 (61) | 21 (55) | |

| 1 missing | 1 missing | |||

| Alcohol use | Yes | 15 (75) | 15 (83) | 30 (79) |

| No | 5 (25) | 3 (17) | 8 (21) | |

| Body mass index (BMI) | Normal | 8 (40) | 10 (56) | 18 (47) |

| BMI > 25 | 12 (60) | 8 (44) | 20 (53) | |

| Problematic BD use (subscale of Bendep-SRQ) | Low | 6 (30) | 2 (11) | 8 (21) |

| Average | 3 (15) | 2 (11) | 5 (13) | |

| High | 11 (55) | 13 (72) | 23 (61) | |

| 1 missing | 1 missing | |||

None of the differences were statically significant at the 5% level (χ2-test)

Twenty-two participants had tried to stop BD use in the past, and 12 of them experienced a high level of withdrawal symptoms.

In total 21 patients discontinued the use of BD after the taper off: 12 in the melatonin group and nine in the placebo group (Table 2). After one year 15 patients remained (40%) without BD sleeping medication (eight out of 20 in the melatonin group and seven out of 18 in the placebo group). This difference was not significant.

Table 2.

Follow up after one year. Use of BD sleeping medication after the taper off and during follow up. Separate data for the melatonin and placebo group

| Stopped on T1 | Did not resume on T2 | Definitely stopped on T3 | Melatonin *** on T3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melatonin group (n = 20) | 12 | 10 | 8* | 2 |

| Placebo group (n = 18) | 9 | 7 | 7* (1**) | 1 |

| Total | 21 | 17 | 15 | 3 |

T1 = at the time of stopping the use of melatonin or placebo (six weeks after the taper off of BD)

T2 = after six months

T3 = after one year

* One person in the placebo group and one in the melatonin group stopped participation in the trial after the taper off. According to their GPs, they no longer used any BD at T3

** One person had resumed using BD at T2, but stopped again at T3. He is not counted as a definite stopper

*** Three persons received melatonin from their GP after discontinuing the use of melatonin in the trial

The urine analysis showed that two patients in the placebo group, who had reported that they had stopped using BD, were still positive. They had received new prescriptions of BD at one and three months after T3, although at a lower dose.

At the end of the trial three persons used melatonin, two in the melatonin group and one in the placebo group. Of the patients who had stopped, four had switched to a herb product (valerian, Valdispert®) or homeopathic product (Nervogin®, passiflora).

The patients who had totally discontinued BD use were compared with the non-stoppers in terms of gender, age, weight, period of use, PDD, sleeping quality, general health experience and awareness of problematic use. We found small differences, which were not statistically significant at the α = 0.05 level (Table 3). Of the patients who had already used BD for five years or more, 35% stopped compared to 43% of the patients with a shorter period of use. For high daily use (PDD/DDD ≥ 1), this was 33% compared to 41% for daily use <1. Of the patients who were aware of their problematic use, 54% stopped compared to 29% among the others.

Table 3.

Putative indicators of discontinuation of benzodiazepines (numbers and percentages)

| Definite stoppers | Non-stoppers | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 6 (38%) | 10 (62%) | 16 |

| Female | 9 (41%) | 13 (59%) | 22 |

| Age <65 | 6 (33%) | 12 (67%) | 18 |

| Age 65+ | 9 (45%) | 11 (55%) | 20 |

| Body mass index <25 | 6 (33%) | 12 (67%) | 18 |

| Body mass index ≥25 | 9 (45%) | 11 (55%) | 20 |

| Period of use <5 year | 6 (43%) | 8 (57%) | 14 |

| Period of use ≥5 year | 8 (35%) | 15 (65%) | 23 (1 missing) |

| PDD/DDD < 1.0 | 12 (41%) | 17 (59%) | 29 |

| PDD/DDD ≥ 1.0 | 3 (33%) | 6 (67%) | 9 |

| Awareness of problematic use, low | 7 (29%) | 17 (71%) | 24 |

| Awareness of problematic use, high | 7 (54%) | 6 (46%) | 13 (1 missing) |

| General health, low | 6 (40%) | 9 (60%) | 15 |

| General health, high | 9 (41%) | 13 (59%) | 22 (1 missing) |

| Sleeping quality, bad | 8 (36%) | 14 (64%) | 22 |

| Sleeping quality, good | 6 (50%) | 6 (50%) | 12 (4 missing) |

None of the differences were statistically significant at the 5% level (χ2 test)

Four of the 19 patients who had stopped at T1 reported a high level of withdrawal symptoms during the taper off. We have no data for two people because they did not complete the questionnaire.

To measure the effects of discontinuation we compared the scores of T0 (initial measurement) with those at T3 (final measurement). In terms of health experience, there were no differences between the stoppers and non stoppers according to the scores on nine scales of the RAND questionnaire, sleeping quality, alcohol consumption, or smoking.

Discussion

In our trial, we could not confirm the positive outcome of Garfinkel et al. [10]. Our findings are in agreement with those of Cardinali et al. [11].

The success rate of our study was 40%, higher than of that of spontaneous stopping (10–15%) [19, 20] and stopping after an informative letter or minimal intervention strategy (25%) [3–5]. This may be caused by the use of our taper-off program, the selection by some GPs and the selective response, including the awareness of problematic use (in two-thirds of the participants). In general, readiness to stop using BD sleeping medication was low. In our trial we fell well short of the discontinuation rate in the melatonin group of the trial of Garfinkel et al. (14 out of 18).

After a minimum intervention, it appears that of the stoppers after two years only half remain without this medication [21]. In our trial, 55% of the participants had stopped shortly after the taper off. However, after a year this dropped to 40%. We omitted any supportive measures during follow up as much as possible in order to measure the pure effect of melatonin.

The gender difference in our selected population (n = 503) is comparable to figures in the literature [1]. BD use among Garfinkel et al.’s patients was higher than ours (only nine of our patients had PPD/DDD ≥ 1.0). It has been shown that patients on a rather low dose of BD discontinue their use more easily and resume their BD use less rapidly [21]. For patients with a high daily use melatonin may still be valuable. If there will be future discontinuation trials there is reason to especially include patients who use a high dose of BD.

In our trial, in contrast to that of Garfinkel et al., at the end only 9% still used melatonin. Four participants changed their use to a homeopathic or phytotherapeutic medication, which indicates a basic need to use something for their sleeping problem.

Half of the patients who tried to stop by themselves before participating in our study, without taper off, suffered from withdrawal symptoms. In our trial this was 25%, showing the advantage of gradual tapering. We did not find a shift of addiction behavior, sleep quality or general health among stoppers of BD.

Conclusions

Our trial does not provide conclusive evidence that melatonin is helpful for BD discontinuation.

The overall question about the effectiveness of intervention remains. Another trial, in contrast to the first trial, shows a negative result. One should consider that the results of all three trials are influenced by a possible selection bias or lack of power, due to the low number of participants.

Further investigation is necessary, with special attention to the effect of the daily dose on stopping the use of BD. Finally one should take into account the difficulty of recruiting BD users for stop studies.

Acknowlegdements

We acknowledge the help of Marion Gijbels and Karin Aretz, research assistants, and the pharmacist of the Academic Hospital of Maastricht, Leo Stolk. We would also like to thank the participating GPs and their assistants in the health centers: Heer, dr. van Kleef and the general practices of A. Wintjens, V. Zwietering, B. Schilte, R. Lauw, T. van Merode-W. Goudriaan, J. Screever and P. Wielders in Maastricht.

Footnotes

Frans H. J. A. Vissers passed away in September 2006

References

- 1.GIP-Signal: Use of benzodiazepines 1993–1998. Geneesmiddelen Informatie Project (GIP)/College voor zorgverzekeringen. Amstelveen, 2000.

- 2.Knuistingh Neven A, Graaff de WJ, Lucassen PLBJ, Springer MP, Bonsema K, Dijkstra RH. NHG-standard Insomnia and sleeping medication. Huisarts Wet 1992;35: 209–12.

- 3.Cormack MA, Sweeney KG, Hughes-Jones Foot GA. Evaluation of an easy, cost effective strategy for cutting benzodiazepine use in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 1994;44:5–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Oude Voshaar RC, Gorgels WJM, Mol AJJ, et al. Treatments to discontinue long-term use of benzodiazepines. Ned Tijdschr Geneesk 2001;145:1347–50. [PubMed]

- 5.Niessen WJM, Sewart RE, Broer L, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM. Decrease of benzodiazepines of long-term users by a letter of their own GPs. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2005;149 (7):356–61. [PubMed]

- 6.Anonymus. Discontinuation of benzodiazepines. Gebu 1994;28(12):98–101.

- 7.Oude Voshaar RC, Gorgels WJM, Mol AJJ, Balkom van AJLM, Lisdonk van de EH, Breteler MHM, Hoogen van den HJM, Zitman FG. Tapering off long-term benzodiazepine use with or without group cognitive-behavioural therapy: three-condition, randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2003;182:498–504. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Nagtegaal JE. Pharmaceutical, chronobiological and clinical aspects of melatonin. [PhD thesis] Amsterdam 2001; ISBN 90-9015249-0.

- 9.Olde Rikkert MG, Rigaud AS. Melatonin in elderly patients with insomnia. A systematic review. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2001;34(6):491–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Garfinkel D, Zisapel N, Wainstein J, Laudon M. Facilitation of benzodiazepine discontinuation by melatonin. A new clinical appraoch. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:2456–60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Cardinali DP, Gvozdenovich E, Kaplan MR, Fainstein I, Shifis HA, Perez Lloret S, Albornoz L, Negri A. A double blind-placebo controlled study on melatonin to reduce anxiolytic benzodiazepine use in the elderly. Neuro Endocrin Lett 2002;23(1):55–60. [PubMed]

- 12.Lamberts H, Wood M. ICP, International Classification of Primary Care. Oxford University Press, New York 1987. ISBN 90-5170-279-5.

- 13.Diest van R, Milius H, Markusse R, Snel J. The sleep wake experience list. T Soc Gezondheidsz 1989;10:343–7.

- 14.Mulder-Hajonides van der Meulen WREH. The Groningen sleep quality scale. In: Proceedings of the 14th CINP congress. Florence: Italy; 1984.

- 15.van der Zee KI, Sanderman R. Measuring general health with RAND-36: a manual. Groningen 1993: Noordelijk Centrum voor Gezondheidsvraagstukken, NCG. ISBN 90-72156-60-9.

- 16.Kan C. Structured appraoches to the Asessment of Benzodiazepine Dependence. The development of the Benzodiazepine Dependence Self-Report Questionnaire. [PhD thesis] Nijmegen 2000; ISBN 90-9013945-1.

- 17.Benzodiazepines in urine. Cobas Integra 700, Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany.

- 18.Zitman FG, Couvée JE. Chronic benzodiazepine use in general practice patients with depression: an evaluation of controlled treatment and taper off. Br J Psychiatry 2001;178: 317–24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Vissers FHJA. Use of sleeping and sedative medication in daily practice. Determinants, consequences and the role of the GP. [PhD thesis] Maastricht 1998; ISBN 90-5681-047-2.

- 20.Holden JD, Hughes IM, Tree A. Benzodiazepine prescribing and withdrawal for 3234 patients in 15 general practices. Fam Pract 1994;11:358–62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Oude Voshaar RC, Gorgels WJMJ, Mol AJJ, van Balkom AJLM, Breteler MHH, van de Lisdonk EH, Mulder J, Zitmans FG. Predictors of relapse after discontinuation of long-term benzodiazepine use by minimal intervention: 2-year follow-up study. Fam Pract 2003;20(4):370–72. [DOI] [PubMed]