Abstract

Objectives

To examine the effect of walking and vitamin B supplementation on quality-of-life (QoL) in community-dwelling adults with mild cognitive impairment.

Methods

One year, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Participants were randomized to: (1) twice-weekly, group-based, moderate-intensity walking program (n = 77) or a light-intensity placebo activity program (n = 75); and (2) daily vitamin B pills containing 5 mg folic acid, 0.4 mg B12, 50 mg B6 (n = 78) or placebo pills (n = 74). QoL was measured at baseline, after six and 12 months using the population-specific Dementia Quality-of-Life (D-QoL) to assess overall QoL and the generic Short-Form 12 mental and physical component scales (SF12-MCS and SF12-PCS) to assess health-related QoL.

Results

Baseline levels of QoL were relatively high. Modified intention-to-treat analyses revealed no positive main intervention effect of walking or vitamin supplementation. In both men and women, ratings of D-QoL-belonging and D-QoL-positive affect subscales improved with 0.003 (P = 0.04) and 0.002 points (P = 0.06) with each percent increase in attendance to the walking program. Only in men, SF12-MCS increased with 0.03 points with each percent increase in attendance (P = 0.08).

Conclusion

Several small but significant improvements in QoL were observed with increasing attendance to the walking program. No effect of vitamin B supplementation was observed.

Trial Registration

International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number Register, 19227688, http://www.controlled-trials.com/isrctn/.

Keywords: Quality of life, Aged, Exercise, Dietary supplements, Randomized controlled trial

Introduction

Especially in older people, both mental and physical function decrease due to multiple age related changes, which in turn may affect quality of life (QoL). The most obvious decrease in mental function is cognitive decline, which is a common aspect of aging. However, in some cases decline is more serious than expected for a certain age. This is specified as Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI). MCI is considered to be a potential transitional stage between normal cognitive function and Alzheimer’s disease, characterized by (1) subjective memory complaint (2) objective memory impairment (3) normal mental status (4) intact activities of daily living (ADL) (5) absence of dementia [1]. Independent of the latter four criteria, subjective memory complaints are related to lower QoL [2]. Moreover, MCI is associated with poor physical health and high risk of ADL dependence [3, 4]. Since both cognitive and physical decline belong to the most important determinants of QoL in community dwelling elderly subjects [5], subjects with MCI are likely to be susceptible to a decrease in QoL.

The number of adults with MCI is increasing considerably due to the aging population. For multiple reasons, it is important to prevent a decrease in QoL. Apart from the personal benefits, a high rated QoL also reduces medical consumption and helps to maintain independency as long as possible [6]. This in turn may relieve significant others, caregivers and medical society in general. For this reason, attention should be paid to possible interventions contributing towards a higher level of overall QoL and it’s mental and physical components. In this respect, physical exercise and vitamin supplementation are interesting interventions worth investigating. Regular participation in moderate intensity aerobic training is reported to be beneficial in improving QoL and wellbeing, which is an important aspect of QoL [7, 8]. Since walking is the most prevalent physical activity among older adults [9], improving QoL by increasing the time spent on moderate intensity walking seems promising. Indeed, a community based walking program significantly improved both the physical and mental components of health-related QoL in older adults (n = 582) [10]. Inconclusive evidence has been reported on the influence of vitamin B supplementation on QoL. Different aspects of QoL were not responsive to short term supplementation (range 4–12 weeks) with different doses and combinations of B vitamins in men and women [11–13].

Not much is known about QoL in community dwelling elderly with MCI. Moreover, no trials on the effect of exercise and vitamin B supplementation on QoL have been carried out yet in adults with MCI. The FACT-study (Folate physical Activity Cognition Trial) was developed to examine the effect of these interventions on cognition [14]. Aspects of QoL were measured as a secondary outcome. In the present paper, the effectiveness of 1 year moderate intensity walking (two sessions of 60 min per week) and daily vitamin supplementation (5 mg folate, 50 mg vitamin B6 and 0.4 mg B12) on both overall QoL and it’s health-related components is examined in community dwelling older adults with MCI. We hypothesize that 1 year moderate intensity walking benefits QoL. Concerning the effect of vitamin supplementation, this paper should be considered as explorative.

Methods

Study design

The study was designed as a randomized, placebo controlled intervention trial, based on a two-by-two factorial design. The study-protocol has been described in detail elsewhere [14] and was approved by the VU University Medical Center medical ethics committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Participants

In a medium-sized Dutch town community dwelling subjects aged 70–80 years with MCI were identified using a population based two-step-screening [15]. The operational criteria for MCI according to the criteria of Petersen et al. [1] and additional inclusion criteria for the RCT are described in Table 1. Subjects were not paid to participate in the study.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for participation in the trial

| Operationalization of Petersen criteria for MCI (1–5) and additional inclusion criteria for the RCT (6–12) |

|---|

| 1. Memory complaints (answer yes to question ‘do you have memory complaints’, or at least twice sometimes at cognition scale of Strawbridge [16] |

| 2. Objective memory impairment; 10 WLT delayed recall ≤5 + percentage savings ≤ 100 [17] |

| 3. Normal general cognitive functioning; TICS ≥ 19 + MMSE ≥ 24 [18, 19] |

| 4. Intact daily functioning: no report of disability in activities of daily living on GARS-scale, except on the item ‘taking care of feet and toe nails’ [20] |

| 5. Absence of dementia; TICS ≥ 19 + MMSE ≥ 24 |

| 6. Being able to perform moderate intensity physical activity, without making use of walking devices, e.g., a rollator or a walking frame |

| 7. Not using vitamin supplements/vitamin injections/drinks with dose of vitamin B6, B11 or B12 comparable to vitamin supplement given in intervention |

| 8. Not suffering from epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, kidney disorder requiring haemodialysis, psychiatric impairment |

| 9. Not suffering from depression as measured by the GDS (cut off ≤5) [21] |

| 10. Not using medication for rheumatoid arthritis or psoriasis interfering with vitamin supplement |

| 11. No alcohol abuse (men < 21 consumptions a week, women < 15 consumptions a week) |

| 12. Not currently living in a nursing home or on a waiting list for a nursing home |

MCI = Mild Cognitive Impairment, RCT = Randomized Controlled Trial, 10 WLT = 10 Word Learning Test, TICS = Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status, MMSE = Mini Mental State Examination, GARS = Groningen Activity Restriction Scale, GDS = Geriatric Depression Scale

Randomization

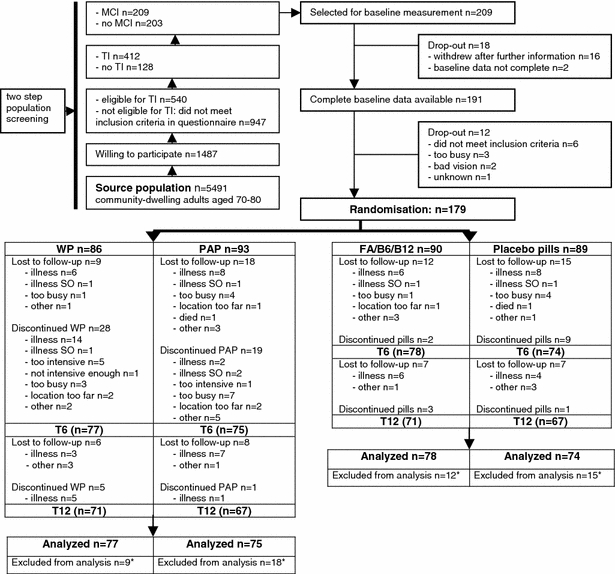

After the baseline interview, subjects were randomly assigned to the interventions using the statistical computer program SPSS. Intervention groups were: (1) walking program or placebo activity program; and (2) vitamin B supplementation or placebo supplementation. Randomization was stratified for physical activity level at baseline in minutes per day as measured by the LASA physical activity questionnaire [22]. For the flow of participants see Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart. TI = Telephone Interview, WP = Walking Program, PAP = Placebo Activity Program, FA/B12/B6 = Folic Acid, Vitamin B12, Vitamin B6 supplementation, SO = significant other, T6 = follow-up after 6 months, T12= follow-up after 12 months, *reason for exclusion: only baseline data available

Exercise intervention

Subjects assigned to the walking program (WP) participated twice a week 60 min in group-based moderate intensity walking during 1 year. Each session consisted of a warming up, moderate intensity walking exercises and a cooling down. The WP was based on ‘Sportive Walking,’ an existing aerobic walking program [23] aimed at improving cardiovascular endurance. Therefore, duration and intensity of the walking exercises increased gradually during the program. Sessions took place outdoor in municipal parks. Subjects not assigned to the WP participated in a placebo activity program (PAP) with the same frequency, session duration and program duration. However, the PAP consisted of low intensity exercise, such as light range of motion movements and stretching. Sessions were divided into five themes: relaxation, activities of daily living, balance, flexibility, posture and a combination of all. For each theme three sessions were developed and the entire series of 18 sessions was repeated during the intervention period. The PAP was carried out in community centers. Both programs were supervised by qualified and trained instructors. Attendance to both programs was assessed by the percentage of attended sessions.

Vitamin supplementation (FA/B12/B6)

Subjects in the vitamin supplementation group took one pill containing 5 mg vitamin B11 (Folic Acid), 0.4 mg vitamin B12 (Cyanocobalamin) and 50 mg vitamin B6 (Pyridoxine-hydrochloride) daily during 1 year. This vitamin supplement is available on prescription in The Netherlands. Subjects randomized to the control group took an identically looking placebo pill. The pills were packed in blister packs for 1 week, which were labeled for each day of the week. Compliance with the vitamin supplementation was verified by pill counts in returned blister packs during the intervention.

Outcome measures

Baseline data on sociodemographic and background variables were collected using a postal screening questionnaire. The measurement of other baseline variables, as reported in Table 2, has been described elsewhere [14]. In the present manuscript a distinction was made between ‘overall quality of life,’ referring to a subjects overall enjoyment of life and ‘health-related quality of life,’ referring to health-related factors affecting quality of life. The term QoL was used as an umbrella term for both overall and health-related QoL. The population-specific Dementia Quality of Life questionnaire (D-QoL) [24] was used to assess overall QoL and the generic Short Form 12 (SF12) [25] to assess health-related QoL. The D-QoL is a 29 item measure especially developed for elderly with cognitive decline and dementia. The participant is asked about how much they enjoyed activities that were reported to be important for elderly such as ‘watching animals.’ Moreover, the frequency of certain positive and negative feelings such as ‘lovable’ or ‘worried’ were asked for. Finally, they were asked to rate their overall quality of life. The participant was instructed to choose the best fitting answer from five item response scales. The answers were divided into five domains of QoL measuring sense of aesthetics, feelings of belonging, negative affect, positive affect/humor and self esteem. A mean score ranging from one to five was calculated for these subscales and for the total D-QoL. A higher score indicated better quality of life. Median internal consistency reliability of the D-QoL was 0.80 and median test–retest reliability was 0.72 in a sample of 95 older adults with different stages of cognitive decline [24]. The SF12 consists of 12 items measuring eight concepts of both mental and physical health, i.e., physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, energy, social functioning, role emotional and mental health. These concepts are subdivided into two summary scores using a norm-based criterion: i.e., mental and physical component summary scales (SF12-MCS and SF12-PCS). The mean score is 50 with a standard deviation of 10. For example, a score of 60 corresponds to a-QoL rating of one standard deviation above the average ratings in the general population. Test retest reliability for the SF-12 MCS was 0.76 in a sample of 187 adults in the United Kingdom and 0.77 in a sample of 232 adults in the United States. Reliability coefficients of the SF-12 PCS in these populations were 0.86 and 0.89, respectively [25]. In the present study, measurement took place during a personal interview at baseline and after 6 and 12 months. Both the D-QoL and the SF-12 were administered by a trained interviewer who was unaware of the participants’ group allocation.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of participants (n = 152)

| Exercise intervention | Vitamin intervention | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WP (n = 77) | PAP (n = 75) | FA/B12/B6 (n = 78) | Placebo-pill (n = 74) | |

| Age (Mean (SD)) | 75 (2.9) | 75 (2.8) | 75 (2.8) | 75 (2.9) |

| Gender (% male) | 48* | 64 | 56 | 55 |

| MMSE (Median (10th–90th ‰)) | 29 (26–30) | 29 (27–30) | 29 (25–30) | 29 (27–30) |

| Education (% low/middle/high) | 61/22/17 | 52/29/19 | 57/26/17 | 55/26/19 |

| Marital status (% living together) | 75 | 68 | 69 | 73 |

| Physical activitya (min/day) (Median (10th–90th ‰)) | 44 (10–155) | 39 (11–120) | 45 (13–155) | 38 (9–111) |

| Vitamin status (% deficient FA/B12/B6)b | 46/8/0 | 48/8/0 | 49/9/0 | 45/7/0 |

| Homocysteine statusc (% hyperhomocysteinemia) | 27 | 23 | 27 | 23 |

| Blood pressure (% hypertension)d | 27* | 14 | 25 | 16 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (Median (10th–90th p‰)) | 26.7 (23.1–31.5) | 26.6 (23.5–32.7) | 26.5 (23.3–32.8) | 26.7 (23.5–31.2) |

| Smoking (% smokers) | 13 | 15 | 17 | 11 |

| Number of self-reported diseases (% 0,1,2)e | 52/42/6 | 69/27/4 | 66/28/6 | 55/41/4 |

WP = Walking Program, PAP = Placebo Activity Program, FA/B12/B6 = Folic Acid, Vitamin B12, Vitamin B6 supplementation, MMSE = Mini Mental State Examination, Education: low = no education, primary education, lower vocational training; intermediate = intermediate level secondary education, intermediate vocational training; high = higher level secondary education, higher vocational training, university training. BMI = Body Mass Index

a ≥3.0 metabolic equivalents

b Cut off points: FA red blood cell <337 nmol/l or FA plasma < 6,3 nmol/l; B12 ≤ 150 pmol/l; B6 < 20 nmol/l

c Homocysteine > 14 mmol/l

d Hypertension = diastole ≥ 90 and systole ≥160

e Cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, psychiatric disease, renal failure requiring dialysis and/or rheumatoid arthritis

* Significantly different from PAP (P < 0.05)

Statistical analyses

Differences between groups on baseline characteristics were tested using independent t-tests (normally distributed variables), Mann–Whitney U tests (not normally distributed variables) and χ2 (categorical variables). Within group differences were tested using dependent t-tests.

Subsequently, data were analyzed according to a modified intention-to-treat principle, based on data from all randomized participants who provided data at baseline and at least one follow-up measurement. To evaluate the effects of the walking program and the vitamin supplementation on QoL, longitudinal regression analysis was used. The two follow-up measurements were defined as dependent variable and multi level analysis with two levels was used, (1) time of follow-up measurement (values corresponding with performance after six and 12 months intervention); (2) individual. According to the study protocol [14], the effect of both interventions was examined independently from each other. Data were analyzed using a crude and an adjusted model. Independent variables were exercise intervention and vitamin intervention. By analyzing both interventions in the same model, results were adjusted for the possible influence of the other intervention. Moreover, all analyses were adjusted for baseline performance on the outcome measure by adding this as a covariate. In the adjusted model, education, baseline activity level, baseline vitamin status, attendance to the exercise program and compliance with the supplementation were added as covariates. Interaction between gender and the WP or FA/B6/B12-supplementation was checked in the adjusted model. In the case of significant interaction, results were reported for men and women separately. In the case of no interaction, gender was added to the adjusted model as an additional covariate. Also, in the ‘adjusted model’ an interaction effect of the exercise program with attendance to the exercise program was checked. Finally, data were analyzed according to the per protocol principle, including all participants who attended at least 75% of the sessions. This cut-off point is in concordance with previous exercise intervention studies in older adults [26, 27].

Data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows (release 12.0.1). A significance level of 5% was used for between group comparisons and of 10% for interaction terms. For all analyses, regression coefficients and 95% confidence intervals for the adjusted models were reported, with the regression coefficients directly indicating the difference in QoL ratings between the WP and the PAP or the FA/B12/B6-supplementation versus placebo supplementation. In the case of significant interaction, regression coefficients and the 95% confidence intervals of the interaction terms were reported.

Results

Patient characteristics

Hundred-seventy-nine participants were randomized to the interventions. Twenty-seven of them were excluded from the analyses, because they only provided baseline data. These subjects were more often married (71% vs. 52%, P = 0.05) and less often current smokers (0% vs. 14%, P = 0.04) than the remaining 152 participants who provided QoL data at baseline and at at least one follow-up measurement. The latter 152 participants were included in the analyses (see Fig. 1). Their mean age (SD) was 75 (2.9) years. Fifty-six percent was male. Additional baseline variables are described per factor in Table 2. Compared to the PAP, the WP included fewer men (48% in WP vs. 64% in PAP) and more subjects with hypertension (27% in WP vs. 14% in PAP). Ratings for both overall and health-related QoL at baseline and after 6 and 12 months intervention are presented in Table 3. No baseline differences were observed on these measures, except for a higher rating of D-QoL self-esteem in subjects in the FA/B12/B6-group compared to subjects in the placebo-supplementation group.

Table 3.

Means (standard deviations) of QoL ratings at baseline and after 6 and 12 months in older adults with MCIa

| WP | PAP | FA/B12/B6 | Placebo | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 (n = 77) | T6 (n = 77) | T12 (n = 71) | T0 (n = 75) | T6 (n = 75) | T12 (n = 67) | T0 (n = 78) | T6 (n = 78) | T12 (n = 71) | T0 (n = 74) | T6 (n = 74) | T12 (n = 67) | |

| D-QoL sumscore | 3.5 (0.26) | 3.5 (0.29) | 3.5 (0.27) | 3.5 (0.32) | 3.5 (0.34) | 3.5 (0.34) | 3.5 (0.32) | 3.5 (0.32) | 3.5 (0.33) | 3.4 (0.24) | 3.5 (0.31) | 3.5 (0.27) |

| D-QoL aesthetics | 3.5 (0.63) | 3.5 (0.64) | 3.6 (0.60) | 3.5 (0.70) | 3.5 (0.71) | 3.5 (0.65) | 3.5 (0.64) | 3.5 (0.68) | 3.6 (0.61) | 3.4 (0.68) | 3.5 (0.67) | 3.6 (0.64) |

| D-QoL belonging | 3.7 (0.50) | 3.7 (0.49) | 3.7 (0.44) | 3.8 (0.45) | 3.7 (0.47) | 3.7 (0.46) | 3.8 (0.50) | 3.6 (0.50) | 3.6 (0.48) | 3.7 (0.44) | 3.8 (0.45) | 3.8 (0.40) |

| D-QoL negative affect | 2.7 (0.45) | 2.7 (0.46) | 2.8 (0.50) | 2.7 (0.55) | 2.8 (0.54) | 2.8 (0.52) | 2.7 (0.54) | 2.8 (0.47) | 2.8 (0.53) | 2.7 (0.47) | 2.7 (0.53) | 2.8 (0.49) |

| D-QoL positive affect | 3.8 (0.39) | 3.7 (0.46) | 3.8 (0.40) | 3.8 (0.40) | 3.7 (0.44) | 3.8 (0.43) | 3.8 (0.41) | 3.7 (0.47) | 3.8 (0.44) | 3.8 (0.39) | 3.8 (0.43) | 3.8 (0.39) |

| D-QoL self esteem | 3.6 (0.45) | 3.8 (0.41) | 3.8 (0.40) | 3.7 (0.48) | 3.7 (0.49) | 3.8 (0.48) | 3.8 (0.48)* | 3.8 (0.48) | 3.9 (0.48) | 3.6 (0.43) | 3.7 (0.43) | 3.7 (0.38) |

| SF12-MCS | 54.6 (6.85) | 55.6 (6.40) | 55.3 (4.39) | 54.7 (8.07) | 55.0 (7.34) | 55.3 (6.24) | 55.5 (7.49) | 55.9 (6.91) | 55.8 (4.90) | 53.8 (7.36) | 54.6 (6.86) | 54.8 (5.76) |

| SF12-PCS | 48.2 (7.15) | 48.1 (7.57) | 50.5 (6.13) | 48.7 (7.86) | 48.8 (8.47) | 49.8 (7.04) | 47.9 (8.20) | 47.4 (8.79) | 49.8 (6.68) | 49.1 (6.67) | 49.6 (7.00) | 50.6 (6.49) |

MCI = Mild Cognitive Impairment, WP = Walking Program, PAP = Placebo Activity Program, FA/B12/B6= Folic Acid, Vitamin B12, Vitamin B6 supplementation, D-QoL = Dementia Quality of Life, SF12-MCS = Short Form 12 Mental Component Summary, SF12-PCS = Short Form 12 Physical Component Summary

a Higher rating indicates better QoL

* P < 0.05 (difference between FA/B12/B6 and placebo)

Attendance to the WP and the PAP

Overall median attendance to the exercise programs (10th−90th percentile) was 63 (0–89) percent and did not differ between the WP and the PAP. Especially in the first weeks, a considerable number of subjects discontinued participation, mostly because they did not want to participate in the exercise programs after all. Most frequent reasons for discontinuation of the program after the first weeks were health-related problems. No adverse events of the WP or PAP itself were reported. Adherent subjects attending at least 75% of the sessions (n = 51) were more often living together (82% vs. 65%, P = 0.03) and less physically active than non-adherers (n = 101), (median [10th–90th percentile] was 36 [13–82] vs. 44 [10–169] min/day, P = 0.02). At baseline, adherers also had lower ratings of D-QoL-belonging (3.6 [0.41] vs. 3.8 [0.49], P = 0.02) and higher SF12-MCS values (56.5 [5.6] vs. 53.7 [8.1], P = 0.02). Other baseline and QoL characteristics did not differ significantly.

Compliance with the (FA/B12/B6)supplementation

Four participants did not return the blister packs. On the basis of pill counts in returned blister packs, median compliance (10th–90th percentile) with the FA/B12/B6-supplementation was 100 (97–100) percent and compliance with placebo-supplementation was 100 (35–100) percent. Even though median compliance in both groups was 100%, compliance in the placebo-group was significantly lower (P < 0.05). Eight subjects, one in the FA/B12/B6-group and seven in the placebo-group, did not take (vitamin)supplementation. Seven of them decided immediately after randomization not to participate in the interventions. The other wanted to participate in the exercise intervention only. Two participants discontinued taking vitamin pills during the trial after reporting sleep problems and increased forgetfulness; one participant discontinued taking the placebo pills after reporting not feeling well.

Modified intention to treat analyses

Results of the walking program and FA/B6/B12 supplementation are presented in Table 4. With respect to overall QoL, no positive significant main effect of the WP or FA/B6/B12 supplementation was found. A significantly detrimental effect of FA/B6/B12 supplementation was observed on D-QoL-belonging, (beta (95%CI) = −0.18 (−0.29; −0.07), P < 0.01). A positive interaction between the WP and attendance to the WP was observed on D-QoL-belonging and D-QoL-positive affect. With each percent increase in attendance, D-QoL-belonging increased with 0.003 points (P = 0.04) and D-QoL-positive affect with 0.002 points (P = 0.06) in the WP compared to the PAP. With respect to health-related QoL, an interaction between the WP and gender was observed on the SF12-MCS (P = 0.06) and therefore analysis for the SF12-MCS was stratified for gender. No main effects of the WP or FA/B12/B6-pills were observed. However, in men in the WP, SF12-MCS increased with 0.03 points with each percent increase in attendance (P = 0.08).

Table 4.

Results of longitudinal multi level analyses on the effect of the WP and FA/B6/B12 supplementation on change in QoL (adjusted model)

| WP versus PAP Beta (95%CI) | P-value | FA/B12/B6 versus placebo Beta (95%CI) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-QoL sumscore | 0.04 (−0.03;0.10) | 0.25 | −0.06 (−0.12;0.004) | 0.07 | |

| D-QoL aesthetics | 0.06 (−0.07;0.20) | 0.37 | −0.07 (−0.20;0.07) | 0.33 | |

| D-QoL belonging | 0.00 (−0.11;0.11) | 0.96 | −0.18 (−0.29; −0.07) | 0.00 | |

| D-QoL negative affect | −0.02 (−0.12;0.08) | 0.65 | 0.04 (−0.05;0.14) | 0.37 | |

| D-QoL positive affect | 0.04 (−0.04;0.13) | 0.34 | −0.04 (−0.12;0.04) | 0.33 | |

| D-QoL self esteem | 0.08 (−0.02;0.18) | 0.11 | 0.00 (−0.10;0.11) | 0.94 | |

| SF12-PCS | 0.66 (−1.23;2.54) | 0.49 | −0.73 (−2.65;1.19) | 0.45 | |

| SF12-MCS* | Men | −0.82 (−2.24;0.60) | 0.25 | 0.25 (−1.31;1.81) | 0.76 |

| Women | 1.66 (−1.50;4.81) | 0.30 | 1.32 (−1.93;4.56) | 0.42 | |

WP = Walking Program, PAP = Placebo Activity Program, FA/B12/B6= Folic Acid, Vitamin B12, Vitamin B6 supplementation, D-QoL = Dementia Quality of Life, SF12-MCS = Short Form 12 Mental Component Summary, SF12-PCS = Short Form 12 Physical Component Summary

* Interaction WP and gender

Per protocol analyses

Subgroup analyses were performed in subjects attending 75% or more of the WP or PAP sessions (n = 51, 33 men and 18 women). No between group differences were observed for FA/B12/B6-pills versus placebo-pills. A significant positive effect of the WP compared to the PAP was observed on D-QoL-positive affect, beta (95%CI) = 0.23 (0.06; 0.39), P < 0.01 and a borderline significant positive effect on D-QoL-self esteem, beta (95%CI) = 0.17 (0.001; 0.34), P = 0.05.

Discussion

No positive main effect of walking or daily FA/B6/B12 supplementation was observed on QoL in community-dwelling adults with MCI. However, ratings of overall QoL (i.e., feelings of belonging, positive affect) and the mental component of health-related QoL improved slightly with increasing attendance to the walking program. In a subgroup that attended at least 75% of the sessions, a beneficial effect of the walking program was observed on positive affect and self esteem.

To our knowledge, this is the first intervention study on QoL in community-dwelling adults with MCI. While memory complaints are reported to be negatively associated with QoL in healthy older adults with subjective memory complaints [2], QoL ratings in our study population were already quite high at baseline. Baseline ratings on the DQOL sumscore and subscales fell ample above the midpoint of the scale, except for negative affect. Baseline scores on the SF-12MCS fell around a half standard deviation above the average in the general population and SF-12PCS fell about the average ratings. QoL-ratings have been reported to decrease as the severity of cognitive decline increases [28]. The possibility exists that MCI as operationalized in the present study may not have been serious enough to negatively influence overall and health-related QoL. In spite of the high baseline values, the QoL scales still allowed for further improvements, i.e., there was no ceiling effect. However, it has been discussed before that QoL may represent a stable concept, which is difficult to change or that existing measures may not be responsive to subtle changes [29].

The relationship between physical activity and QoL has been studied extensively. However, it is difficult to draw a clear conclusion, since various definitions and operationalizations of QoL circulate. Moreover, comparisons between studies are being complicated by the wide variety of study populations and features of exercise intentions such as intensity, exercise mode, frequency and session and total duration [30]. However, Rejeski et al. [31] concluded in a review including 28 studies, of which 11 RCT’s, that physical activity positively influenced aspects of health-related QoL. In a recent meta-analysis of Netz et al. [7] including 36 studies, a small positive effect of exercise was observed on wellbeing in healthy older adults. In that meta-analysis four components of wellbeing were considered, including aspects that were also measured in the FACT-study, such as positive and negative affect, perception of physical fitness and physical symptoms.

In the present study no main effects of the WP were observed in the modified intention to treat analyses. First, a possible explanation for the lack of effect may be that only participants with good QoL were able to attend enough sessions. In contrast to an earlier study, no baseline differences in number of chronic diseases, physical health-related QoL and endurance were observed between adherers (attending ≥75% of the sessions) and non-adherers (attending <75% of the sessions) [32]. However, adherers rated their mental health-related QoL at baseline significantly better than non-adherers. The difference was three points, which approximately equaled a difference of 5%. The possibility exists that subjects with lower mental health-related QoL were inclined to attend less sessions. Nevertheless, it is not likely that this biased our results, because non-adherers and drop-outs from the exercise programs were included in the modified intention to treat analyses. In future studies in subjects with cognitive decline, session attendance may be improved by informing subjects extensively about the study aims and the consequences of participation. Moreover, if possible with respect to logistic and financial issues, we advice to schedule time and staff for the close personal follow-up of temporary drop-outs.

Second, it has been reported that the association between physical activity and QoL is lower among older adults who function at or above the norm [31]. By applying inclusion criteria for the present trial (e.g., community dwelling, no ADL disabilities, being able to perform moderate intensity physical activity), we presumably selected physically healthy and active subjects. This is supported by the high baseline activity levels. Two-thirds of the participants reported to be physically active at moderate intensity for 30 min or more per day. Subjects meeting this guideline are reported to have better health-related QoL than physically inactive adults [8]. Additionally, Netz et al. found that larger effects of exercise on wellbeing were observed in sedentary adults [7]. However, in the present study, no interaction between the walking program and baseline physical activity level was observed (results not presented), indicating that inactive participants did not benefit more from the WP than active participants. Therefore, it is not likely that baseline physical activity level was a main cause of the lack of main effects.

Finally, inconclusive evidence is available about the intensity and exercise mode of physical activity required to benefit QoL. Netz et al. [7] concluded that aerobic training of moderate intensity was most beneficial for wellbeing. In a cross-sectional study, it was also observed that moderate intensity physical activity was positively related to health-related QoL [8]. In contrast, in a review by Spirduso and Cronin [33] no evidence of a relationship between exercise intensity and the rate of improvement in QoL was found. If the former would be true, the possibility exists that the contrast between both programs in the present study would not have been large enough to induce differences in QoL. If the latter would be true, participants would have benefited from participation in both exercise programs regardless of intensity. Both programs may either have added to better self-efficacy, or may prevented a decline in self-efficacy. The walking program by training cardiovascular endurance; the placebo activity program by training e.g., balance and ADL. Self-efficacy refers to somebody’s belief that one has the capabilities to successfully manage situational demands and is mentioned to be a mediating mechanism for the effect of physical activity on QoL [7, 30, 34, 35]. Thus, the presence of the low intensity placebo activity program in our study may have contributed towards the lack of between group differences.

Nevertheless, several outcomes improved with increasing attendance to the walking program. In the per protocol analyses a beneficial effect was observed on positive affect. Self esteem also tended to improve. However, observed differences were small and approximated 5% differences from baseline QoL ratings. As a rule of thumb, a minimal change of 5% has been mentioned to signify clinical relevance. To obtain a change of 5% by increasing attendance, the required increase in attendance would be 62% for D-QoL-belonging and 94% for D-QoL-positive affect and the SF12-MCS. Therefore, it can be questioned whether the observed effects are clinically relevant.

No effect of the FA/B12/B6 supplementation was observed except for a negative effect on feelings of belonging. However, no theoretical rationale exists for this effect. Our findings are in line with previous RCT’s on the effect of vitamin B supplementation on aspects of QoL. Deijen et al. [11] observed no effect of supplementation with 20 mg vitamin B6 for 3 months on mood in healthy men (n = 76). Also no effect of supplementation with 750 μg folate, 15 μg vitamin B12 or 75 mg vitamin B6 daily for 35 days was observed on mood in women aged 65 or over (n = 75) [11]. Finally, no effect on health-related QoL was observed of a weekly injection with 1 mg vitamin B12 for 4 weeks in adults with vitamin B12 deficiency (n = 140) [13]. These findings may find its origin in the used operationalizations and measures of QoL that include very few items that directly relate to nutrition. Amarantos et al. [36] underline the need to develop QoL measures including items that relate nutrition to QoL.

To conclude, the walking program and vitamin B supplementation were not effective in improving QoL in community-dwelling older adults with MCI within 1 year. However, increasing attendance to moderate intensity physical activity may benefit certain aspects of QoL.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the municipality of Alkmaar and the ‘Stichting Fonds voor het Hart’ for financially supporting project FACT and VIATRIS bv for providing us with the vitamin and placebo pills. None of these sponsors had input into protocol development, data collection, analyses, or interpretation. We appreciate the assistance of Jos Twisk, PhD, in providing guidance on appropriate statistical methods. We also acknowledge the hard work of Lyda ter Hofstede and the other research assistants who contributed to the FACT-study.

Abbreviations

- ADL

activities of daily living

- D-QoL

dementia quality of life

- FA/B12/B6

folic acid, vitamin B12, vitamin B6

- MCI

mild cognitive impairment

- PAP

placebo activity program

- QoL

quality of life

- SF-12

short form 12

- SF12-MCS

SF-12 mental component summary

- SF12-PCS

SF-12 physical component summary

- WP

walking program

References

- 1.Petersen, R. C., Smith, G. E., Waring, S. C., Ivnik, R. J., Tangalos, E. G., & Kokmen, E. (1999). Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Archives Neurology, 56, 303–308. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Mol, M., Carpay, M., Ramakers, I., Rozendaal, N., Verhey, F., & Jolles, J. (2006). The effect of perceived forgetfulness on quality of life in older adults; a qualitative review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Frisoni, G. B., Fratiglioni, L., Fastbom, J., Guo, Z., Viitanen, M., & Winblad, B. (2000). Mild cognitive impairment in the population and physical health: data on 1,435 individuals aged 75–95. Journals of Gerontology Series A-Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 55, M322–M328. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Gill, T. M., Richardson, E. D., & Tinetti, M. E. (1995). Evaluating the risk of dependence in activities of daily living among community-living older adults with mild to moderate cognitive impairment. Journals of Gerontology Series A-Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 50: M235–M241. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Borowiak, E., & Kostka, T. (2004). Predictors of quality of life in older people living at home and in institutions. Aging Clinical Experimental Research, 16, 212–220. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Shephard, R. J. (1993). Exercise and aging—extending independence in older adults. Geriatrics, 48, 61–64. [PubMed]

- 7.Netz, Y., Wu, M. J., Becker, B. J., & Tenenbaum, G. (2005). Physical activity and psychological well-being in advanced age: A meta-analysis of intervention studies. Psychology and Aging, 20, 272–284. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Vuillemin A., Boini, S., Bertrais, S., Tessier, S., Oppert, J. M., & Hercberg, S. et al. (2005). Leisure time physical activity and health-related quality of life. Preventive Medicine, 41, 562–569. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.DiPietro, L. (2001). Physical activity in aging: Changes in patterns and their relationship to health and function. Journals of Gerontology Series A-Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 56, 13–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Fisher, K. J., & Li, F. (2004). A community-based walking trial to improve neighborhood quality of life in older adults: A multilevel analysis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 28, 186–194. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Bryan J., Calvaresi, E., & Hughes, D. (2002). Short-term folate, vitamin B-12 or vitamin B-6 supplementation slightly affects memory performance but not mood in women of various ages. Journal of Nutrition, 132, 1345–1356. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Deijen J. B., van der Beek, E. J., Orlebeke, J. F., & van den, B. H. (1992). Vitamin B-6 supplementation in elderly men: Effects on mood, memory, performance and mental effort. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 109, 489–496. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Hvas, A. M., Juul, S., Nexo, E., & Ellegaard, J. (2003). Vitamin B-12 treatment has limited effect on health-related quality of life among individuals with elevated plasma methylmalonic acid: a randomized placebo-controlled study. Journal of International Medicine, 253, 146–152. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.van Uffelen, J. G. Z., Hopman-Rock, M., Chin A Paw, M. J. M., & van Mechelen, W. (2005). Protocol for Project FACT: A randomised controlled trial on the effect of a walking program and vitamin B supplementation on the rate of cognitive decline and psychosocial wellbeing in older adults with mild cognitive impairment [ISRCTN19227688]. BMC Geriatrics, 5, 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.van Uffelen, J. G., Chin A Paw, M. J. M., Klein, M., van Mechelen, W., Hopman-Rock M (2006). Detection of memory impairment in the general population: screening by questionnaire and telephone compared to subsequent face-to-face assessment. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Strawbridge, W. J., Shema, S. J., Balfour, J. L., Higby, H. R., & Kaplan, G. A. (1998). Antecedents of frailty over three decades in an older cohort. Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 53, S9–S16. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Morris, J. C., Heyman, A., Mohs, R. C., Hughes, J. P., van Belle, G., & Fillenbaum, G. et al. (1989). The consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer’s disease (CERAD). Part I. Clinical and neuropsychological assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology, 39, 1159–65. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Brandt, J., Spencer, M., & Folstein, M. (1988). The Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status. Neuropsychiatry, Neuropsychology and Behavioral Neurology, 1, 111–117.

- 19.Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E., & McHugh, P. R. (1975). “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12, 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Kempen, G. I., Miedema, I., Ormel, J., & Molenaar, W. (1996). The assessment of disability with the groningen activity restriction scale. Conceptual framework and psychometric properties. Social Science & Medicine, 43, 1601–1610. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Yesavage, J. A., Brink, T. L., Rose, T. L., Lum, O., Huang, V., & Adey, M. et al. (1982). Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 17, 37–49. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Stel, V. S., Smit, J. H., Pluijm, S. M.F, Visser, M., Deeg, D. J. H., & Lips, P. (2004). Comparison of the LASA Physical Activity Questionnaire with a 7-day diary and pedometer. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 57, 252–258. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Stahl, T., & Laukkanen, R. (2005). A way of healthy walking—A guidebook for health promotion practice. http://www.reumaliitto.fi/walking-guide/guide/guide.doc. 26-01-2000. 15-09-2005. .

- 24.Brod, M., Stewart, A. L., Sands, L., & Walton, P. (1999). Conceptualization and measurement of quality of life in dementia: the dementia quality of life instrument (DQoL). Gerontologist, 39, 25–35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Ware, J.E., Kosinski, M., & Keller, S.D. (1995). SF-12: How to score the SF-12 physical and mental health summary scales, 2nd edn. Boston, MA: The health institute, New England Medical Center.

- 26.Chin A Paw, M. J. M., van Poppel, M. N., Twisk, J. W., & van Mechelen, W. (2004). Effects of resistance and all-round, functional training on quality of life, vitality and depression of older adults living in long-term care facilities: a ‘randomized’ controlled trial [ISRCTN87177281]. BMC Geriatrics, 4, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.King, A. C., Haskell, W. L., Taylor, C. B., Kraemer, H. C., & DeBusk, R. F. (1991). Group- vs home-based exercise training in healthy older men and women. A community-based clinical trial JAMA, 266, 1535–1542. [PubMed]

- 28.Ready, R. E., Ott, B. R., & Grace, J. (2004). Patient versus informant perspectives of Quality of Life in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 19, 256–265. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Chin, A., Paw, M., de Jong, N., Schouten, E. G., van Staveren, W. A., & Kok, F. J. (2002). Physical exercise or micronutrient supplementation for the wellbeing of the frail elderly? A randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 36, 126–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Rejeski, W. J., & Mihalko, S. L. (2001). Physical activity and quality of life in older adults. Journals of Gerontology Series A-Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 56, 23–35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Rejeski, W. J., Brawley, L. R., & Shumaker, S. A. (1996). Physical activity and health-related quality of life. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 24, 71–108. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Schmidt, J. A., Gruman, C., King, M. B., & Wolfson, L. I. (2000). Attrition in an exercise intervention: a comparison of early and later dropouts. Journal of the American Geriatric Society, 48, 952–960. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Spirduso, W. W., & Cronin, D. L. (2001). Exercise dose-response effects on quality of life and independent living in older adults. Medicine and Science in Sports Exercise, 33, S598–S608. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.McAuley, E., Elavsky, S., Jerome, G. J., Konopack, J. F., & Marquez, D. X. (2005). Physical activity-related well-being in older adults: social cognitive influences. Psychology and Aging, 20, 295–302. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Elavsky, S., McAuley, E., Motl, R. W., Konopack, J. F., Marquez, D. X., & Hu, L. et al. (2005). Physical activity enhances long-term quality of life in older adults: Efficacy, esteem, and affective influences. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 30, 138–145. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Amarantos, E., Martinez, A., & Dwyer, J. (2001). Nutrition and quality of life in older adults. Journals of Gerontology Series A-Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 56, 54–64. [DOI] [PubMed]