Abstract

Rational and Objectives:

To compare the performance of computer aided detection (CAD) systems on pairs of full-field digital mammogram (FFDM) and screen-film mammogram (SFM) obtained from the same patients.

Materials and Methods:

Our CAD systems on both modalities have similar architectures that consist of five steps. For FFDMs, the input raw image is first log-transformed and enhanced by a multi-resolution preprocessing scheme. For digitized SFMs, the input image is smoothed and subsampled to a pixel size of 100μm×100μm. For both CAD systems, the mammogram after preprocessing undergoes a gradient field analysis followed by clustering-based region growing to identify suspicious breast structures. Each of these structures is refined in a local segmentation process. Morphological and texture features are then extracted from each detected structure, and trained rule-based and linear discriminant analysis (LDA) classifiers are used to differentiate masses from normal tissues. Two data sets, one with masses and the other without masses, were collected. The mass data set contained 131 cases with 131 biopsy proven masses, of which 27 were malignant and 104 benign. The true locations of the masses were identified by an experienced MQSA radiologist. The no-mass data set contained 98 cases. The time interval between the FFDM and the corresponding SFM was 0 to 118 days.

Results:

Our CAD system achieved case-based sensitivities of 70%, 80%, and 90% at 0.9, 1.5, and 2.6 FP marks/image, respectively, on FFDMs, and the same sensitivities at 1.0, 1.4, and 2.6 FP marks/image, respectively, on SFMs.

Conclusion:

The difference in the performances of our FFDM and SFM CAD systems did not achieve statistical significance.

Keywords: Computer-Aided Detection, Mass Detection, Full-Field Digital Mammogram (FFDM), Screen-Film Mammogram (SFM), Free-Response Receiver Operating Characteristic (FROC)

I. INTRODUCTION

Full-field digital mammography (FFDM) and screen-film mammography (SFM) are two available methods for breast cancer screening in current clinical practice. FFDM detectors provide higher detective quantum efficiency (DQE) and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), wider dynamic range, and higher contrast sensitivity than SFM. FFDM may alleviate some of the limitations of SFM, especially in breasts with dense fibroglandular tissue(1). In the last few years, several FFDM systems became commercially available because of the potential of digital imaging to improve breast cancer detection.

Several clinical trials have been conducted to compare radiologists' interpretation on FFDMs and SFMs. Lewin et al.(2, 3) conducted a clinical study to compare FFDMs and SFMs for the detection of breast cancer in 6737 examinations of women 40 years of age and older collected from two institutions. Forty-two cancers were detected within this population. The difference in cancer detection was not statistically significant (p>0.1) between FFDMs and SFMs. FFDMs resulted in fewer recalls than did SFM which was statistically significant (p<0.001). Another clinical trial(4) aiming at collecting data for FDA approval included SFMs and FFDMs of 676 women who were scheduled to undergo breast biopsy. The average area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, the sensitivity and the specificity were 0.715, 0.66 and 0.67 for printed FFDM and 0.765, 0.74, 0.60 for SFM, respectively. However, none of these differences achieved statistical significance. Skaane et al.(5-7) has conducted several clinical studies to compare SFM and FFDM with soft-copy interpretation for reader performance in detection and classification of breast lesions. According to their findings, there was no significant difference between FFDM and SFM either in detection or in classification. A recent study by Pisano et al.(1) collected a total of 49,528 patients at 33 sites in the US and Canada. Mammograms were interpreted independently by two radiologists. The overall diagnostic accuracy of FFDMs and SFMs for breast cancers was similar. However, FFDM was more accurate in women under the age of 50 years, women with radiographically dense breasts, and premenopausal or perimenopausal women.

Studies indicate that radiologists do not detect all carcinomas that are visible upon retrospective analyses of the images(8-14). Computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) is considered to be one of the promising approaches that may improve the sensitivity of mammography(15, 16). Most of the mammographic CAD systems developed so far are based on digitized SFMs. Li et al. (17) attempted to adapt their CAD system developed on SFMs for detection of masses on FFDMs by standardizing the FFDMs. Their preliminary results on a small data set (training on 36 normal and 24 mass cases, testing on 24 normal and 10 mass cases) showed 60% sensitivity at 2.47 FPs/image. Several commercial CAD systems reported comparable performance on FFDMs and SFMs. However, their study was not reported in peer-reviewed journals so that the data set and algorithm are unknown. So far, there are no studies on comparison of breast mass detection between FFDMs and SFMs from the same patients by using CAD system. We have developed a CAD system for mass detection on SFMs(18, 19) and are adapting the system to FFDMs. Our preliminary study with 65 patients was reported previously(20). In this study, we compared the performance of the two CAD systems on case-matched pairs of FFDMs and SFMs.

II. MATERIALS AND METHOD

2.1 Materials

Our study group consisted of patients with breast lesions that were categorized suspicious and recommended for biopsy. The patients had either FFDM or SFM for their clinical exams. IRB approval and patient informed consent were obtained to acquire corresponding mammograms of the breast to be biopsied using the other modality. Therefore, the corresponding FFDM and SFM were available only from one breast for each patient. The time interval between the SFM and the FFDM ranged from 0 to 118 days. The data set consisted of 229 patients aged from 30 to 86 with a mean age of 55±11 years. All cases have two mammographic views, the craniocaudal (CC) view and the mediolateral oblique (MLO) view or the lateral view, thus yielding a total of 458 FFDMs and 458 corresponding SFMs. The SFMs were acquired with MinR2000 screen-film systems (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY) and digitized with a LUMISCAN 85 laser film scanner (Lumisys, Los Altos, Calif) at a pixel resolution of 50μm×50μm and 4096 gray levels. The digitizer was calibrated so that gray-level values were linearly proportional to the optical density in the range of 0–4, with a slope of 0.001 per pixel value. The digitizer output was linearly converted so that a large pixel value corresponded to a low optical density. FFDMs were acquired with a GE Senographe 2000D system (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, Wis). The GE system has a CsI phosphor/a:Si active matrix flat panel digital detector with a pixel size of 100μm×100μm and 14 bits per pixel. The raw FFDMs were used as the input of our CAD system.

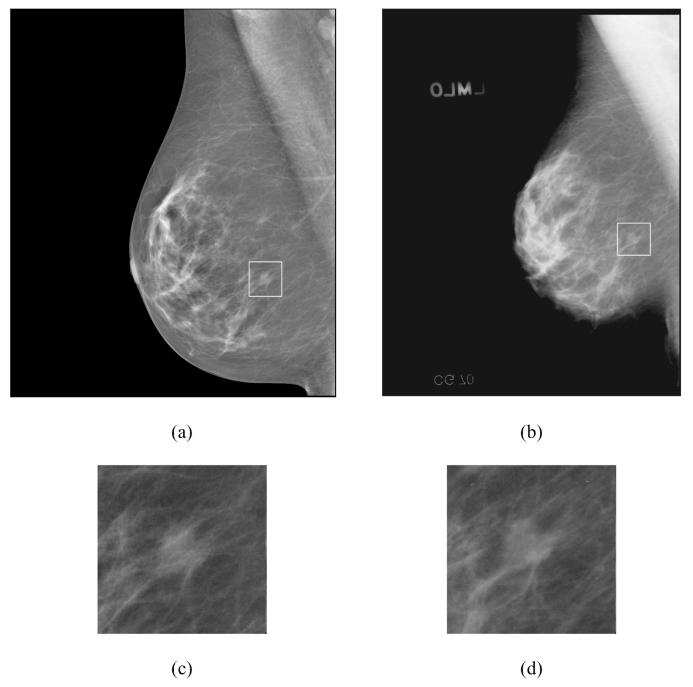

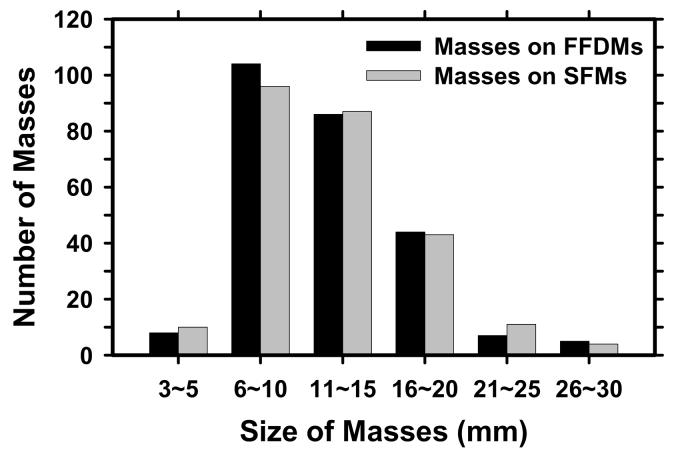

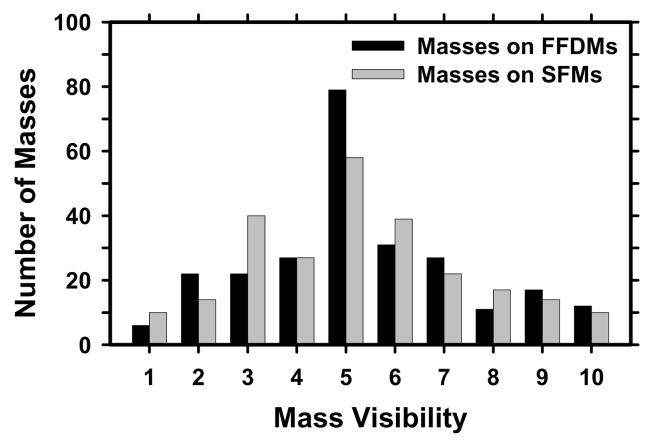

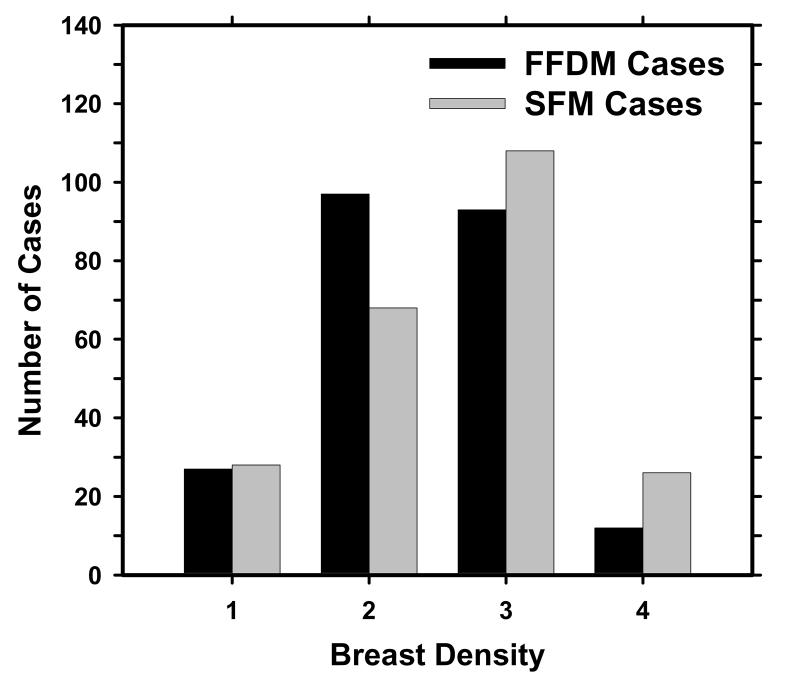

The data set included 131 cases containing masses and 98 cases containing microcalcifications without a visible mass, as determined with visual inspection by an experienced radiologist. The 131 cases will be referred to as the mass data set and the 98 cases as the “no-mass” data set in the following discussion. The no-mass cases were considered as “normal” with respect to masses and were used to estimate the FP mark rates of the CAD systems during testing. The mass data set contained 131 biopsy proved masses of which 27 were malignant and 104 benign. By examining all available information including the diagnostic mammograms and reports, the true locations of the masses were identified by an experienced MQSA radiologist. In these 131 mass cases, 1 mass can be seen only on FFDMs, 7 masses can be seen on only one view on both FFDMs and SFMs, and 3 masses can be seen on only one view on either FFDMs (1 mass) or SFMs (2 masses). There were therefore 131 visible masses on FFDMs and 130 visible masses on SFMs if the masses were counted by case. There were 254 visible and 8 invisible masses on FFDMs and 251 visible and 11 invisible masses on SFMs if the masses were counted independently by mammographic view. The number of images and masses in the mass data set are described in Table I. Figure 1 shows an example with a 7-mm malignant mass. The size of a mass was estimated as its longest diameter seen on the mammograms. The visibility of the masses was rated by the experienced radiologist on a 10-point scale with 1 representing the most visible masses and 10 the most difficult case relative to the cases seen in clinical practice. Figures 2 and 3 show the histograms of mass sizes and visibility, respectively, for the mass set. The mass size ranged from 3 to 30 mm (mean size: 12.5±4.9 mm on FFDMs and 12.6±4.9mm on SFMs) and the visibility ratings extended over the entire range. Figure 4 shows the breast density in terms of BI-RADS category as estimated by the radiologist for the FFDM and SFM data sets.

Table I.

Description of cases in the mass data sets and the subsets for training and testing in the two-fold cross-validation scheme.

| Mass Set | Mass Subset 1 | Mass Subset 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FFDM | SFM | FFDM | SFM | FFDM | SFM | |

| Total no. of cases | 131 | 131 | 65 | 65 | 66 | 66 |

| Total no. of images | 262 | 262 | 130 | 130 | 132 | 132 |

| No. of visible masses (by case) |

131 | 130 | 65 | 65 | 66 | 65 |

| No. of masses only visible on one view |

8 | 9 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 |

| No. of visible masses (by image) |

254 | 251 | 125 | 125 | 129 | 126 |

| No. of visible malignant masses |

27 | 27 | 12 | 12 | 15 | 15 |

| No. of visible benign masses |

104 | 103 | 53 | 53 | 51 | 50 |

Figure 1.

An example of mammograms with a region of interest (ROI) containing a malignant mass with a size of 7 mm. (a) processed FFDM by using the Laplacian pyramid multiscale method, (b) digitized SFM, (c) magnified ROI on FFDM, and (d) magnified ROI on SFM. The SFM is displayed with the same resolution as that of the FFDM. The apparently smaller breast size on SFM is mainly caused by the very dark breast periphery region on the SFM that cannot be seen on the printed image.

Figure 2.

Histogram of the sizes of 254 masses on FFDMs and 251 masses on SFMs in our data set. Mass sizes are measured as the longest dimension of the mass by an experienced MQSA radiologist. The size of the masses in this data set ranged from 3 to 30 mm (mean size: 12.5±4.9 mm on FFDMs and 12.6±4.9 mm on SFMs).

Figure 3.

Histogram of the visibility of the 254 masses seen on FFDMs and 251 masses seen on SFMs in our data set. The visibility is evaluated on a 10-point rating scale with I representing the most visible masses and 10 the most difficult case relative to the cases seen in their clinical practice. Each mass on a mammogram is rated independently by an experienced MQSA radiologist.

Figure 4.

Distribution of the breast density for the 229 cases in terms of BI-RADS category estimated by an MQSA radiologist.

2.2 Methods

2.2.1 CAD system

The major steps in the mass detection systems on FFDMs and SFMs are similar but the feature spaces and classifiers for FP reduction in each system were designed separately to suit the characteristics of FFDMs and SFMs. The two systems are therefore described together below but the differences will be pointed out whenever applicable. Each single CAD system consists of five processing steps: (1) preprocessing, (2) pre-screening of mass candidates, (3) segmentation of suspicious objects, (4) feature extraction and analysis, and (5) FP reduction by classification of normal tissue structures and masses.

FFDMs are generally preprocessed with proprietary methods by the manufacturer of the FFDM system before being displayed to readers. The image preprocessing method used depends on the manufacturer of the FFDM system. To develop a CAD system that is less dependent on the FFDM manufacturer's proprietary preprocessing methods, we use the raw FFDM as input to our CAD system. We have previously developed a multi-scale preprocessing scheme for image enhancement(21). In brief, the raw mammogram is first segmented automatically into the background and the breast region. A logarithmic transform is applied to the image which is then scaled to 12-bit. The Laplacian pyramid method(21, 22) is used to decompose the transformed breast image into multi-scales. A nonlinear weight function based on the pixel gray level from each of the low-pass components is designed to enhance the high-pass components. The processed image is reconstructed by summing the weighted components.

For SFMs, the full resolution digitized mammograms are smoothed with a 2×2 box filter and subsampled by a factor of 2, resulting in images having a pixel size of 100μm×100μm. These images are used as input to the CAD system.

After preprocessing, a two-stage gradient field analysis method(21, 23) is used to identify the mass candidates for either FFDMs or SFMs. In brief, a gradient field analysis is employed in the first stage to identify potential mass candidates based on high values of the initial gradient field. Each potential mass candidate is segmented by a region growing technique. The shape and the gray level information of the segmented object allow adaptive refinement of the gradient field analysis in the second stage. Locations of high radial gradient convergence are then labeled as mass candidates. These suspicious objects are segmented with a k-means clustering method(24). First, a 256x256 pixel ROI centered at the high gradient point is background-corrected(25) and weighted by a Gaussian function with σ=256 pixels. K-means clustering using the pixel values in a background-corrected image and a Sobel filtered image as features is then used to segment the object.

For each suspicious object, eleven morphological features(18) are extracted. A rule-based classifier removes the detected structures that are substantially different from breast masses. Global and local multi-resolution texture analysis(26) are performed in each ROI by using the spatial gray level dependence (SGLD) matrices. Thirteen SGLD texture measures are used. Global texture features are extracted from the entire ROI for 2 scales, 7 distances, and 2 angles. Local texture features are extracted from the local region containing the detected object and the peripheral regions within each ROI for 2 scales, 4 distances, and 2 angles. Therefore, a total of 364 features and 208 features, respectively, are extracted from global and local texture analysis. The feature space for final classification is the combination of morphological features and SGLD texture features. Finally, linear discriminant analysis (LDA) is used to classify masses from normal tissue in the feature space. The discriminant scores are ranked for each mammogram, and any object with a discriminant score that ranks lower than three is eliminated.

2.2.2 Training and test CAD system

Two-fold cross-validation was used for training and testing our CAD system for FFDMs. We randomly separated the mass data sets by case into two independent subsets, subset 1 with 65 cases and subset 2 with 66 cases. The numbers of masses by image and by case for the FFDM and SFM subsets are shown in Table I. The training included selection of proper parameters and features for the classifier in the CAD system. Once the training with one mass subset was completed, the parameters and features were fixed for testing with the other mass subset. The training and test mass subsets were switched and the training and test processes were repeated. The trained CAD systems were also applied to the no-mass data set, which was not used during training, to estimate the FP rate in screening mammograms.

During training, feature selection with stepwise LDA was applied in order to obtain the best feature subset and reduce the dimensionality of the feature space to design an effective classifier. The detailed procedure has been described elsewhere(21, 27, 28). Briefly, at each step one feature was entered or removed from the feature pool by analyzing its effect on the selection criterion, which was chosen to be the Wilks' lambda in this study. Since the appropriate threshold values for feature entry, feature elimination, and tolerance of feature correlation were unknown, we used an automated simplex optimization method to search for the best combination of thresholds in the parameter space. The simplex algorithm used a leave-one-case-out resampling method within the training subset to select features and estimate the weights for the LDA classifier. To have a figure-of-merit to guide feature selection, the test discriminant scores from the left-out cases were analyzed using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) methodology(29). The accuracy for classification of masses and FPs was evaluated as the area under the ROC curve, Az, for the test cases. In this approach, feature selection was performed without the left-out case so that the test performance would be less optimistically biased(30). However, the selected feature set in each leave-one-case-out cycle could be slightly different because every cycle had one training case different from the other cycles. In order to obtain a single trained classifier to apply to the cross-validation test subset, a final stepwise feature selection was performed with the best combination of thresholds, found in the simplex optimization procedure, on the entire training subset to obtain the final set of features and estimate the weights of the LDA. Note that the entire process of feature selection and classifier weight estimation was performed within the training subset. The LDA classifier with the selected feature set was then fixed and applied to the cross-validation test subset. The training and testing processes were performed independently for the two-fold cross-validation sets.

Since we already trained our CAD system for SFMs with a large data set in a previous study(19), we used the trained system without retraining the parameters in this study. For testing, we divided the SFMs into two test data sets which followed the same case grouping as that for FFDMs. The test cases in each subset did not overlap with any training cases used for training the SFM CAD system in the previous study.

2.2.3 Evaluation methods

We used a free-response receiver operating characteristic (FROC) method(31) to assess the overall performance of the CAD scheme on this image set. An FROC curve is obtained by plotting the mass detection sensitivity as a function of FP marks per image as the decision threshold on the LDA classifier scores varies.

The detected individual objects were compared with the “true” mass locations marked by the experienced radiologist, as described above. A detected object was labeled as TP if the overlap between the bounding box of the detected object and the bounding box of the true mass relative to the larger of the two bounding boxes was over 25%. Otherwise, it would be labeled as FP. The 25% threshold was selected as described in our previous study(18).

FROC curves were presented on a per-image and a per-case basis. For image-based FROC analysis, the mass on each mammogram was considered an independent true object; the sensitivity was thus calculated relative to the number of masses by image on each subset of FFDMs or SFMs (Table I). For case-based FROC analysis, the same mass imaged on the two-view mammograms was considered to be one true object and detection of either or both masses on the two views was considered to be a TP detection; the sensitivity was thus calculated relative to the number of masses by case on each subset of FFDMs or SFMs (Table I). The test FROC curve for a given mass subset was estimated by counting the detected masses on the test mass subset for the sensitivity. The FP marker rate was estimated in two ways: one from FPs detected in the same test mass subsets, the other from FPs detected in the no-mass data set. For the latter, we applied the trained CAD system to the entire no-mass data set. The average number of FP marks per image produced by the CAD system at a given sensitivity was estimated by counting the detected objects in these cases at the corresponding decision threshold. Since we used two-fold cross validation method for training and testing, we obtained two test FROC curves, one for each test subset, for each of the modalities. To summarize the results for comparison, an average test FROC curve was derived by averaging the FP rates at the same sensitivity along the FROC curves of the two corresponding test subsets.

In order to compare the performance of our CAD system for FFDMs and SFMs statistically, we applied the alternative free-response ROC (AFROC) method and the jackknife free-response ROC (JAFROC) method developed by Chakraborty et al.(32, 33) to the pairs of FROC curves. In the AFROC method, the FROC data are first transformed by counting the number of false-positive images (FPI) instead of the FPs per image. The LDA score of an FPI is determined by the highest score FP object on the image regardless of how many lower scores FP objects are made on the same image. The ROCKIT curve fitting software and statistical significance tests for ROC analysis developed by Metz et al.(29) can then be used to analyze the AFROC data.

III. RESULTS

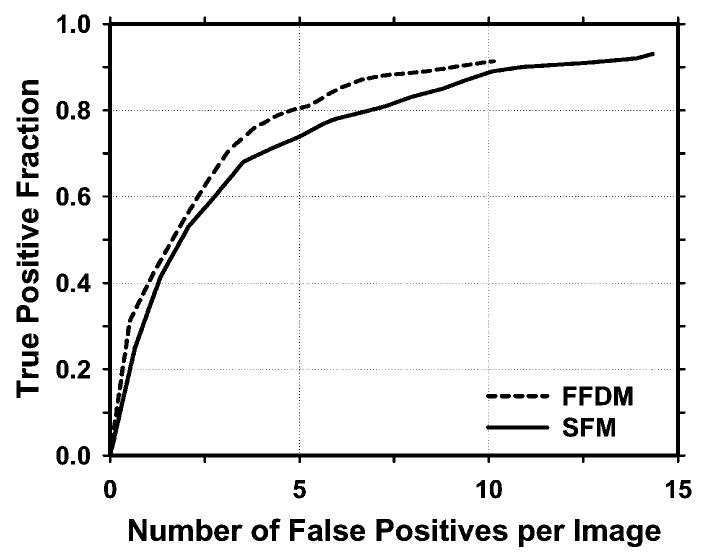

For simplicity, we combine the detection results on the two test subsets from the 2-fold cross-validation process in the following discussion. The pre-screening stage detected 91.3% (232/254) of the masses with an average of 10.13 (2655/262) FPs /image on FFDMs and 93.2% (234/251) with an average of 14.43 (3781/262) FPs/image on SFMs. Figure 5 compares the FROC curves on FFDMs and SFMs during the pre-screening stage. The FROC curves were generated by varying the number of detected suspicious objects per image based on the ranking of local maxima on the gradient field images.

Figure 5.

Comparison of FROC curves on FFDMs and SFMs during the pre-screening stage. The FROC curves were generated by varying the number of detected suspicious objects per image based on the ranking of local maxima on gradient field images. The FP rate was estimated from the mammograms with masses.

We used two steps for FP reduction for both CAD systems. The first step was the rule-based classification based on morphological features. After this step, there were a total of 2572 mass candidates (9.8 objects/image) on FFDMs and 3654 mass candidates (13.9 objects/image) on SFMs without additional FNs for the test sets of 262 images. The second step was the LDA classification. A total of 16 (4 global texture features, 7 local texture features and 5 morphological features) and 12 (4 global texture features, 4 local texture features and 4 morphological features) features, respectively, were selected from the two independent training subsets for FFDMs. The feature set for SFMs contained a total of 21 features (11 global texture features, 7 local texture features and 3 morphological features), as obtained from previous training.

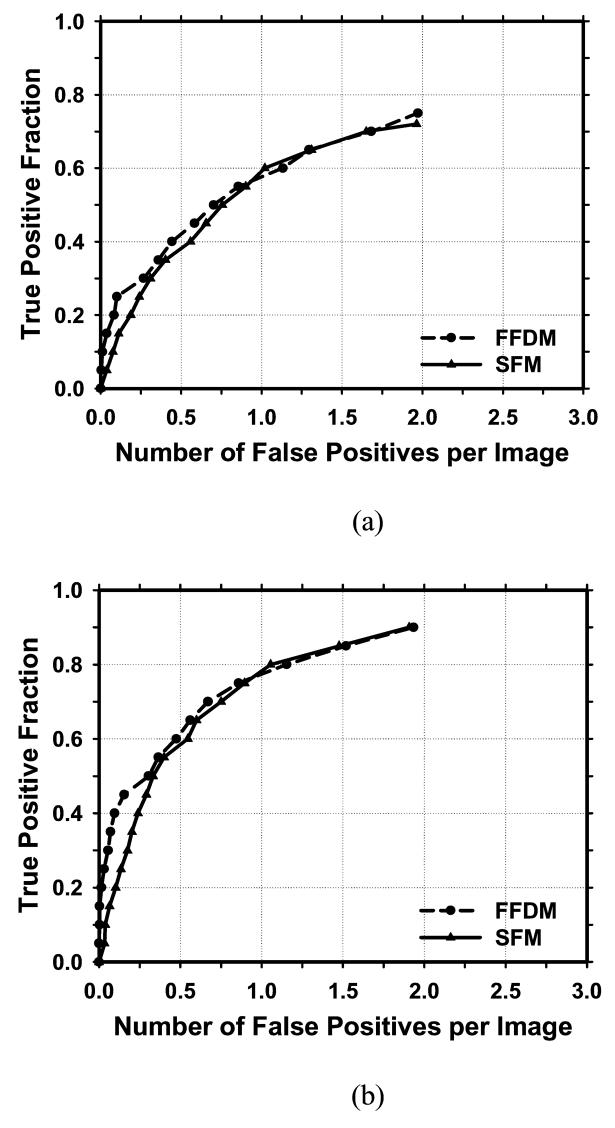

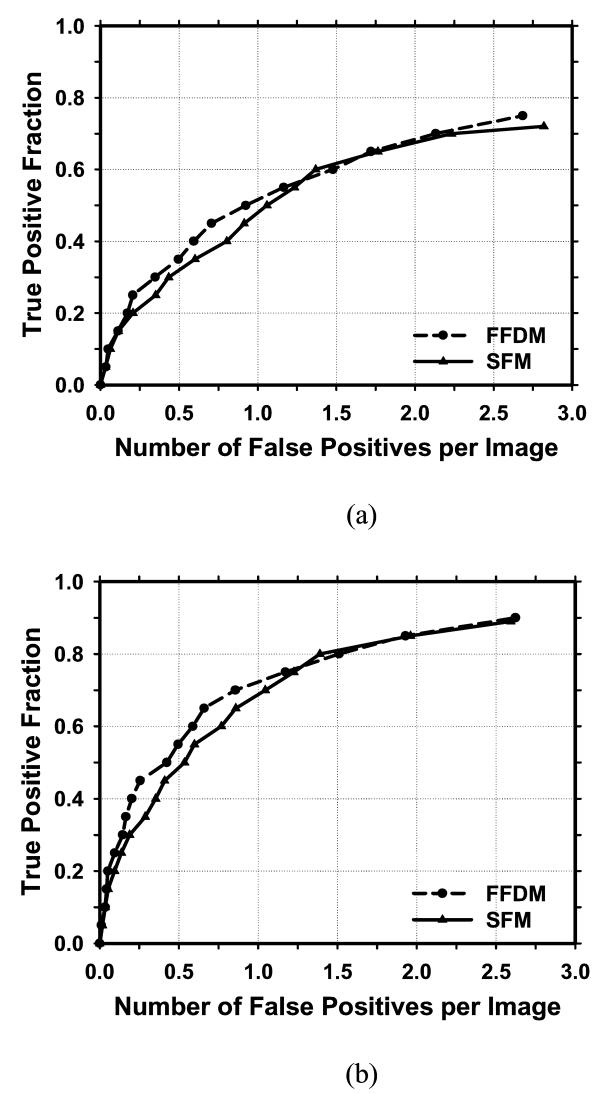

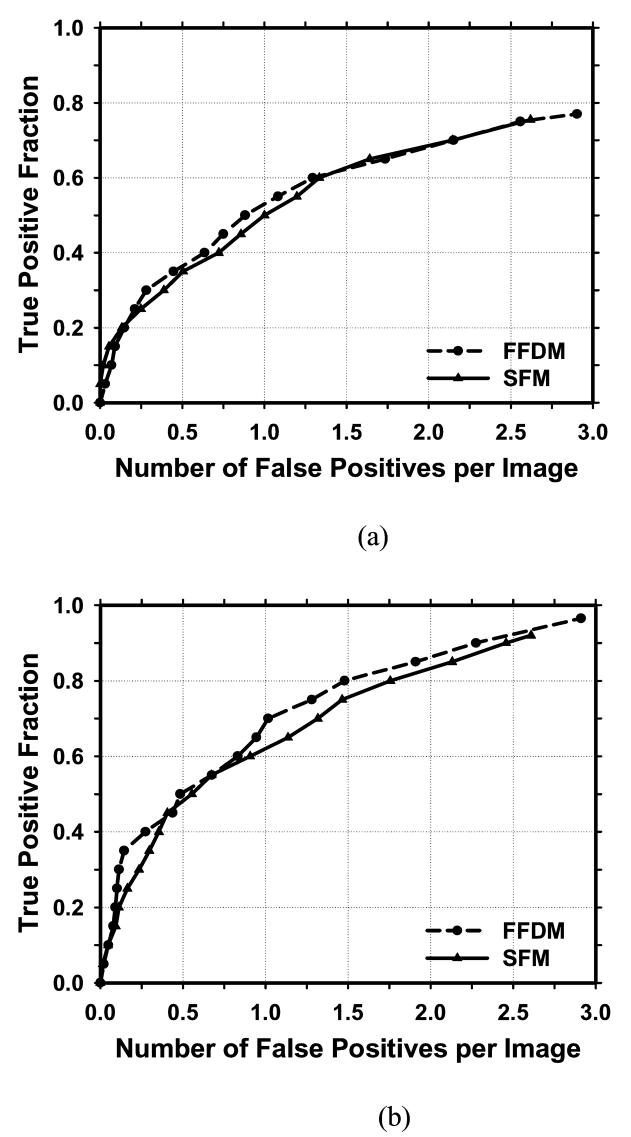

Figure 6 showed the comparison of the average test FROC curves of the CAD systems for FFDMs and SFMs. The FFDM CAD system achieved a case-based sensitivity of 70%, 80%, and 90% at 0.67, 1.15, and 1.93 FPs/image, respectively, compared with 0.75, 1.06, and 1.86 FPs/image for the SFM CAD system. Since two trained CAD systems were obtained for the FFDMs from the cross-validation training, we applied each of the trained systems to the no-mass data set for FROC analysis, and estimated the number of FP marks per image on the no-mass cases at each decision threshold. For each trained CAD system, the sensitivity was estimated from the detected masses on the test mass subset and plotted against the FP rate estimated from the no-mass set. Figure 7 showed the average FROC curves for FFDMs and SFMs, similar to those shown in Figure6, except that the FP rates were estimated from the no-mass data set.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the average test FROC curves obtained from averaging the FROC curves of the two independent mass subsets on FFDMs and SFMs. The FP rate was estimated from the mammograms with masses. (a) Image-based FROC curves, (b) Case-based FROC curves.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the average test FROC curves obtained from averaging the FROC curves of the two independent mass subsets on FFDMs and SFMs. The FP rate was estimated from the mammograms without masses. (a) Image-based FROC curves, (b) Case-based FROC curves.

The comparison of the FROC curves for the FFDM and SFM CAD systems in terms of the area under the fitted AFROC curve (A1) and the p values for both test mass subsets was summarized in Table II. The differences in the A1 values between the two modalities did not achieve statistical significance (p>0.05). The fitted AFROC curves, however, did not fit very well to the transformed AFROC data, as we discussed previously(21). For the JAFROC method, Chakraborty et al. provided software to estimate the statistical significance of the difference between two FROC curves. The comparison of the figure-of-merit (FOM) and the p values was also summarized in Table II. The differences in the FOMs between the FFDM and SFM CAD systems again did not achieve statistical significance (p>0.05).

Table II.

Estimation of the statistical significance of the difference in the FROC performances between the FFDM and SFM CAD systems. The FROC curves with the FP marker rates obtained from the no-mass data set were compared.

| A1 (AFROC) | FOM (JAFROC) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Cases | Malignant Cases | All Cases | Malignant Cases | |||||

| Test subset 1 |

Test subset 2 |

Test subset 1 |

Test subset 2 |

Test subset 1 |

Test subset 2 |

Test subset 1 |

Test subset 2 |

|

| FFDM | 0.48 | 0.49 | 0.51 | 0.49 | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.55 | 0.47 |

| SFM | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.47 | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.41 | 0.48 | 0.42 |

| P values | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.56 | 0.23 | 0.73 | 0.33 | 0.29 | 0.59 |

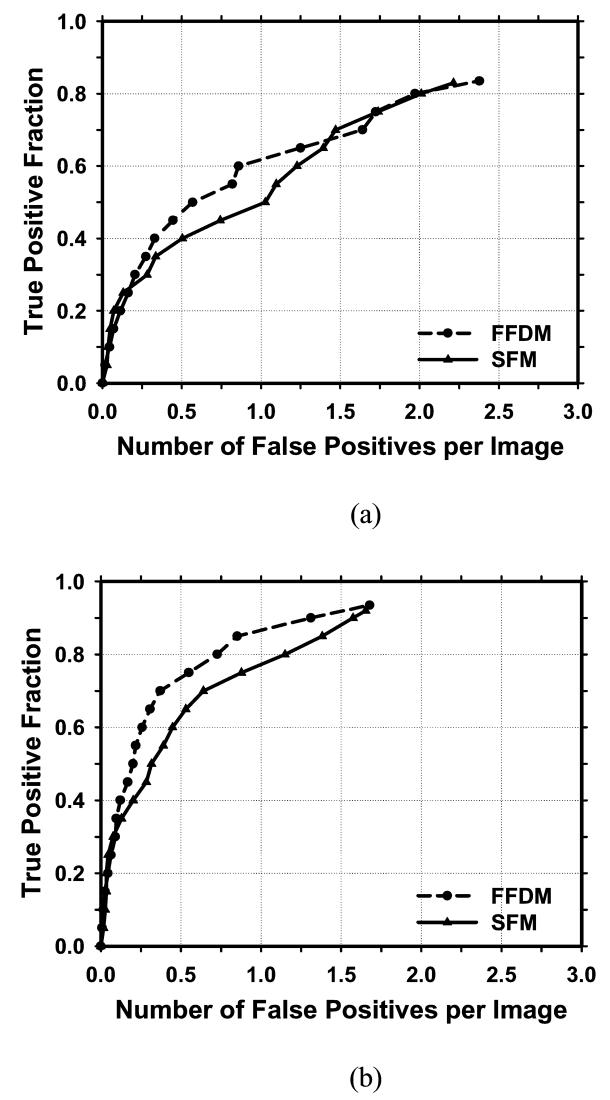

There were 27 malignant cases in the mass set. Figure 8 compared the average test FROC curves of the FFDM and SFM CAD systems for detection of malignant masses. The FP rate was estimated from the no-mass data set. In this case, the FFDM CAD system achieved a case-based sensitivity of 70%, 80%, and 90% at 0.37, 0.73, and 1.31 FP marks/image, respectively, which were substantially better than the FP rates of 1.1, 1.6, and 2.0 FP marks/image for the SFM CAD system. However, the difference did not achieve statistical significance (p>0.05).

Figure 8.

Comparison of the average test FROC curves of CAD systems on FFDMs and SFMs for mammograms with malignant masses. The FP rate was estimated from the mammograms without masses. (a) Image-based FROC curves, (b) Case-based FROC curves.

A total of 105 FFDM cases and 134 SFM cases were identified as BI-RADS 3 and 4 categories by an MQSA radiologist (Figure 4). Of these, 88 cases (56 mass cases and 32 no-mass cases) were in common. Figure 9 compared the average test FROC curves of the FFDM and SFM CAD systems for detection of masses only on this common subset of dense breasts. The FP rate was estimated from the 32 no-mass dense breasts. Although the FROC curve for the FFDMs appears to be slightly higher than that of the SFMs, the difference did not achieve statistical significance (p>0.05).

Figure 9.

Comparison of the average test FROC curves of CAD systems on FFDMs and SFMs for the common subset of 56 dense breasts with masses rated as BI-RADS 3 and 4. The FP rate was estimated from 32 no-mass dense breasts which were also rated as BI-RADS 3 and 4. (a) Image-based FROC curves, (b) Case-based FROC curves.

IV. DISCUSSION

CAD systems have been proven to be helpful as the second opinion to assist radiologists in interpretation of SFMs. Recently several studies have been conducted to compare FFDM with SFM in screening cohorts(1, 4, 5, 34). These clinical trials arrived at different conclusions about the advantages or disadvantages of FFDM in comparison to conventional SFM systems. Some of the differences may be attributed to factors such as the mammographic equipment, the study design, the sample sizes, and the reader experience. It is also important to compare the performances of FFDM and SFM CAD systems. In our study, we compared the performance of the two systems on pairs of FFDM and SFM obtained from the same patients at close time intervals.

Several FFDM systems have been approved for clinical applications. Since digital detectors generally have a linear response to x-ray exposure, the raw pixel values are a linear function of the absorbed x-ray energy in the detector. To develop a CAD system that is less dependent on the FFDM manufacturer's proprietary preprocessing methods, we used the raw FFDM as input to our CAD system. Although the spatial resolution and noise properties of the images from different detectors were still different, the use of raw images already reduced one of the major differences between mammograms from different FFDM systems. For preprocessing of the raw FFDMs, we developed a multi-resolution enhancement method. From our observation on the SFMs and the processed FFDMs, the breast tissue on SFMs appears to be denser than that on FFDMs (35). This may be attributed to the harder beam quality used and the Laplacian enhancement on FFDMs. In this study, 134 SFM cases were rated as BI-RADS 3 and 4 categories by an MQSA radiologist, whereas only 105 FFDM cases were rated as BI-RADS 3 and 4. When the FFDM and SFM CAD systems were applied to the small common subset (56 with masses and 32 without masses) of dense breasts rated as BI-RADS 3 and 4, there was no significant difference between their average test FROC curves (Figure 9).

The overall performances of the CAD systems for the two modalities did not demonstrate significant difference for comparisons in either the subsets or the entire data set. One factor may be the substantially smaller number of training samples used for the FFDM CAD system than that for the SFM CAD system, which was trained with a set of 486 SFMs in a previous study(19). We have shown previously that a classifier designed with a larger number of training samples will have better generalization to unknown test cases.(36) Furthermore, since our CAD system was originally developed on SFMs, some of those techniques used may favor SFMs. If new techniques are designed to specifically suit the properties of FFDMs, the biases may be reduced. Further investigations are underway to improve the FFDM CAD system.

We used a two-fold cross-validation method for training and testing of the CAD systems. Feature selection and classifier weight design were performed within the training subset and thus were independent of the test subset. Kupinski et al.(37) showed that feature selection and classifier weight design using the same training set of a limited size will introduce additional optimistic bias to the training result and thus additional pessimistic bias to the test result. Under the constraint of a limited training set, the relative gain or loss in terms of bias if the training set is further split into two subsets for separate feature selection and classifier weight design in comparison to using the entire set of available training samples for both processes is still unknown. The relative efficiency of different resampling techniques in utilization of a limited data set for classifier design with or without feature selection remains an important area of further studies. In screening mammography, the cancer rate is about 3 to 5 per 1000. Most of the mammograms are normal. Therefore, some CAD researchers and users estimate the FP rate using normal mammograms(38-40) because it reflects how the CAD system performs in terms of specificity in a screening setting. Furthermore, for CAD systems that set a maximum number of detected objects at the output, estimating the number of FPs using images with lesions can potentially lead to an optimistic bias for the FROC curve because one of the detected objects will likely be the true lesion. The FP rate can thus be underestimated by as much as 1 per image. In addition, the JAFROC analysis requires that the FP rates be estimated on normal images. We therefore reported the FP rates of our CAD systems on both mammograms with masses and without masses to facilitate comparison with other CAD systems in case investigators may evaluate their FP rates in either way.

Although we collected case-matched cases for comparing the performances of the CAD systems for FFDMs and SFMs, the images may not be exactly matched. Variations due to positioning, compression force, and the difference in time between the two acquisitions would cause differences in the subtlety of the masses on the FFDMs and SFMs. However, assuming that the differences are random, both data sets would include images that have better or worse positioning, for example, than that on the other modality. The differences in the various factors would likely be averaged out over the entire data set. We expect that they might not cause substantial bias in the comparison of the relative performances of the CAD systems for the two modalities.

For a CAD system, its performance for detecting malignant masses is more important than its performance for detecting all masses. We only have 27 malignant cases in this data set. Although the FROC curves for detection of malignant masses (Figure 8) indicated that the FFDM CAD system had a higher sensitivity than that of the SFM CAD system, the differences in the A1 and the FOM did not achieve statistical significance (p>0.05) for either test subsets, as shown in Table II. A large data set is being collected for further comparison of the FFDM and SFM CAD systems for breast cancer cases.

V. CONCLUSION

We compared the performance of our CAD systems for detection of breast masses on case-matched FFDM images and SFM images. The two CAD systems used similar computer vision techniques but their preprocessing methods were different and the FP classifiers were separately trained to adapt to the image properties of each modality. From the comparison of FROC curves, it was found that the FFDM CAD system achieved higher detection sensitivity than the SFM CAD system at the same FP rates for malignant cases. However, the performances of our FFDM and SFM CAD systems for the entire data set were similar. The differences between the two modalities were not statistically significant with both AFROC and JAFROC methods for either the entire data set or the malignant cases alone. Further study is underway to collect a larger data set and to improve the performances of both systems.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by U. S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command grants W81XWH-1-04-1-0475 and DAMD 17-02-1-0214, and USPHS grant CA95153. The content of this paper does not necessarily reflect the position of the government and no official endorsement of any equipment and product of any companies mentioned should be inferred. The authors are grateful to Charles E. Metz, Ph.D., for the LABROC program and to Dev Chakraborty, Ph.D., for the JAFROC program.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference

- 1.Pisano ED, Gasonis C, Hendrick E, Yaffe M. Diagnostic performance of digital versus film mammography for breast-cancer screening. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353:1773–1783. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewin JM, Hendrick RE, D'Orsl CJ, et al. Comparison of full-field digital mammography with screen-film mammography for cancer detection: results of 4,945 paired examinations. Radiology. 2001;218:873–880. doi: 10.1148/radiology.218.3.r01mr29873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewin JM, D'Orsi CJ, Hendrick RE, et al. Clinical comparison of full-field digital mammography and scree-film mammography for detection of breast cancer. AJR. 2002;179:671–677. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.3.1790671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cole E, Pisano E, Brown M, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of Fischer SenoScan digital mammography versus screen-film mammography in a diagnositic mammography population. Acad Radiol. 2004;11:876–880. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skaane P, Young K, Skjennald A. Population-based mammography screening: comparison of screen-film and full-field digital mammography with soft-copy reading --- Oslo I Study. Radiology. 2003;229:877–884. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2293021171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skaane P, Skjennald A. Screen-film mammography versus full-field digital mammography with soft-copy reading: randomized trial in a population-based screening program -- The Oslo II Study. Radiology. 2004;232:197–204. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2321031624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skaane P, Balleyguier C, Diekmann F, et al. Breast lesion detection and classification: Comparison of screen-film mammography and full-field digital mammography with soft-copy reading—Observer performance study. Radiology. 2005;237:37–44. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2371041605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hillman BJ, Fajardo LL, Hunter TB, et al. Mammogram interpretation by physician assistants. AJR. 1987;149:907–911. doi: 10.2214/ajr.149.5.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bassett LW, Bunnell DH, Jahanshahi R, Gold RH, Arndt RD, Linsman J. Breast cancer detection: one versus two views. Radiology. 1987;165:95–97. doi: 10.1148/radiology.165.1.3628795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wallis MG, Walsh MT, Lee JR. A review of false negative mammography in a symptomatic population. Clinical Radiology. 1991;44:13–15. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(05)80218-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harvey JA, Fajardo LL, Innis CA. Previous mammograms in patients with impalpable breast carcinomas: Retrospective vs blinded interpretation. AJR. 1993;161:1167–1172. doi: 10.2214/ajr.161.6.8249720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bird RE, Wallace TW, Yankaskas BC. Analysis of cancers missed at screening mammography. Radiology. 1992;184:613–617. doi: 10.1148/radiology.184.3.1509041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beam CA, Layde PM, Sullivan DC. Variability in the interpretation of screening mammograms by US radiologists - Findings from a national sample. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1996;156:209–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beam V, Sullivan D, Layde P. Effect of human variability on independent double reading in screening mammography. Academic Radiology. 1996;3:891–897. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(96)80296-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shtern F, Stelling C, Goldberg B, Hawkins R. Novel technologies in breast imaging: National Cancer Institute perspective; Society of Breast Imaging Conference; Orlando, Florida. 1995. pp. 153–156. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vyborny CJ. Can computers help radiologists read mammograms? Radiology. 1994;191:315–317. doi: 10.1148/radiology.191.2.8153298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li L, Clark RA, Thomas JA. Computer-aided diagnosis of masses with full-field digital mammography. Academic Radiology. 2002;9:4–12. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(03)80290-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petrick N, Chan HP, Sahiner B, Helvie MA, Paquerault S, Hadjiiski LM. Breast cancer detection: Evalution of a mass detection algorithm for computer-aided diagnosis: Experience in 263 patients. Radiology. 2002;224:217–224. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2241011062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei J, Sahiner B, Hadjiiski LM, et al. Two-view information fusion for improvement of computer-aided detection (CAD) of breast masses on mammograms. SPIE Proc. 2006;6144:241–247. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei J, Sahiner B, Chan HP, Petrick N, Hadjiiski LM, Helvie MA. RSNA 2003. Chicago: Nov 30, 2003. Computer aided diagnosis system for mass detection: comparison of performance on full-field digital mammograms and digitized film mammograms; p. 387. December 5. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei J, Sahiner B, Hadjiiski LM, et al. Computer aided detection of breast masses on full field digital mammograms. Medical Physics. 2005;32:2827–2838. doi: 10.1118/1.1997327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burt PJ, Adelson EH. The Laplacian pyramid as a compact image code. IEEE Transactions on Communications. 1983;COM-31:337–345. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wei J, Sahiner B, Hadjiiski LM, et al. Computer aided detection of breast masses on full-field digital mammograms: false positive reduction using gradient field analysis. Proc. SPIE Medical Imaging. 2004;5370:992–998. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petrick N, Chan HP, Sahiner B, Helvie MA. Combined adaptive enhancement and region-growing segmentation of breast masses on digitized mammograms. Medical Physics. 1999;26:1642–1654. doi: 10.1118/1.598658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sahiner B, Petrick N, Chan HP, et al. Computer-Aided Characterization of Mammographic Masses: Accuracy of Mass Segmentation and its Effects on Characterization. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2001;20:1275–1284. doi: 10.1109/42.974922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wei D, Chan HP, Petrick N, et al. False-positive reduction technique for detection of masses on digital mammograms: global and local multiresolution texture analysis. Medical Physics. 1997;24:903–914. doi: 10.1118/1.598011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norusis MJ. SPSS for Windows Release 6 Professional Statistics. SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hadjiiski LM, Sahiner B, Chan HP, Petrick N, Helvie MA, Gurcan MN. Analysis of Temporal Change of Mammographic Features: Computer-Aided Classification of Malignant and Benign Breast Masses. Medical Physics. 2001;28:2309–2317. doi: 10.1118/1.1412242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Metz CE, Herman BA, Shen JH. Maximum-likelihood estimation of receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves from continuously-distributed data. Statistics in Medicine. 1998;17:1033–1053. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980515)17:9<1033::aid-sim784>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sahiner B, Chan HP, Petrick N, Wagner RF, Hadjiiski LM. Feature selection and classifier performance in computer-aided diagnosis: The effect of finite sample size. Medical Physics. 2000;27:1509–1522. doi: 10.1118/1.599017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Swensson RG. Unified measurement of observer performance in detection and localizing target objects on images. Medical Physics. 1996;23:1709–1724. doi: 10.1118/1.597758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chakraborty DP, Winter LHL. Free-response methodology: Alternate analysis and a new observer-performance experiment. Radiology. 1990;174:873–881. doi: 10.1148/radiology.174.3.2305073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chakraborty DP, Berbaum KS. Observer studies involving detection and localization: modeling, analysis, and validation. Medical Physics. 2004;31:2313–2330. doi: 10.1118/1.1769352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hendrick R, Lewin J, D'Orsi C, et al. Non-inferiority study of FFDM in an enriched diagnositic cohort: comparison with screen-film mammography in 625 women. In: Yaffe MJ, editor. IWDM 2000: 5th International Workshop on Digital Mammography: Medical Physics; 2001. pp. 475–481. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chan H-P, Zhou C, Helvie MA, Roubidoux MA, Bailey JE. RSNA 89th Scientific Assembly. Chicago, IL: 2003. Comparison of mammographic density estimated on digital mammograms and screen-film mammograms; p. 424. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chan HP, Sahiner B, Wagner RF, Petrick N. Classifier design for computer-aided diagnosis: Effects of finite sample size on the mean performance of classical and neural network classifiers. Medical Physics. 1999;26:2654–2668. doi: 10.1118/1.598805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kupinski MA, Giger ML. Feature selection with limited datasets. Medical Physics. 1999;26:2176–2182. doi: 10.1118/1.598821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'Shaughnessy KF, Castellino RA, Muller SL, Benali K. Computer-aided detection (CAD) on 90 biopsy-proven breast cancer cases acquired on a full-field digital mammography (FFDM) system. Radiology. 2001;221:471. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Warren Burhenne LJ, Wood SA, D'Orsi CJ, et al. Potential contribution of computer-aided detection to the sensitivity of screening mammography. Radiology. 2000;215:554–562. doi: 10.1148/radiology.215.2.r00ma15554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brem RE, Hoffmeister JW, Rapelyea JA, et al. Impact of breast density on computer-aided detection for breast cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:439–444. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.2.01840439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]