Abstract

Machado Joseph disease also called spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 (MJD/SCA3) is a hereditary and neurodegenerative movement disorder caused by ataxin-3 with a polyglutamine expansion (mutant ataxin-3). Neuronal loss in MJD/SCA3 is associated with a mutant ataxin-3 toxic fragment. Defining mutant ataxin-3 proteolytic site(s) could facilitate the identification of the corresponding enzyme(s). Previously, we reported a mutant ataxin-3 mjd1a fragment in brain of transgenic mice (Q71) that contained epitopes C-terminal to amino acid 220. In this study, we generated and characterized neuroblastoma cells and transgenic mice expressing mutant ataxin-3 mjd1a lacking amino acids 190–220 (deltaQ71). Less deltaQ71 than Q71 fragments were detected in the cell but not mouse model. The transgenic mice developed an MJD/SCA3-like phenotype and their brain homogenates had a fragment containing epitopes C-terminal to amino acid 220. Our results support the toxic fragment hypothesis and narrow the mutant ataxin-3 cleavage site to the N-terminus of amino acid 190.

Keywords: Machado-Joseph disease, spinocerebellar ataxia type 3, polyglutamine disease, ataxin-3, cleavage fragment, proteolysis, transgenic mouse

Introduction

Machado-Joseph disease (MJD), also called spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 (SCA3), is the most common dominantly inherited cerebellar ataxia in many countries (Matilla et al., 1995; Schols et al., 1995; Durr et al., 1996; Silveira et al., 1998; Jardim et al., 2001). The signs and symptoms include progressive postural instability, gait and limb ataxia, weight loss and, in severe cases, premature death (Fowler, 1984; Sudarsky and Coutinho, 1995). The neuronal loss occurs in selective brains regions (Fowler, 1984; Sudarsky and Coutinho, 1995; Durr et al., 1996).

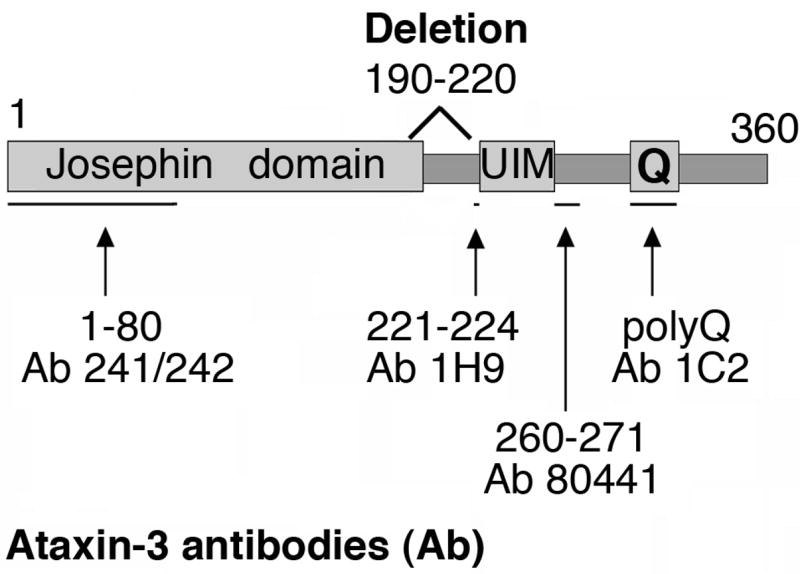

MJD/SCA3 is caused by ataxin-3 with a stretch of 54–84 consecutive glutamines (mutant ataxin-3); normal ataxin-3 has 14–37 (Kawaguchi et al., 1994; van Alfen et al., 2001). Ataxin-3 has functional domains (Fig. 1) and several isoforms resulting from alternative splicing but only mjd1a and ataxin-3c have extended polyglutamines (Kawaguchi et al., 1994; Schmidt et al., 1998; Ichikawa et al., 2001). Mutant ataxin-3 expression is widespread (Ross, 1995; Nishiyama et al., 1996; Paulson et al., 1997; Wang et al., 1997; Schmidt et al., 1998; Trottier et al., 1998), although neuronal loss is selective.

Fig 1.

Diagram of the primary structure of human ataxin-3 mjd1a, the deletion of amino acids 190–220 (deltaQ20 or deltaQ71), and the amino acids recognized by antibodies (Ab) used in Fig. 6B. The amino acid numbers were obtained from the sequence reported for human ataxin-3 mjd1a with a stretch of 22 glutamines (Kawaguchi et al., 1994; Kobayashi and Kakizuka, 2003). The glutamine stretch (Q) is at amino acids 296–317. Ataxin-3 has de-ubiquitinating activity (Josephin domain) at amino acids 1–197 (Burnett et al., 2003; Doss-Pepe et al., 2003; Scheel et al., 2003; Chow et al., 2004; Nicastro et al., 2005), and two ubiquitin interacting motifs (UIM): #1 at amino acids 224–239, and #2 at amino acids 244–259 (Burnett et al., 2003; Miller et al., 2004; Mao et al., 2005).

The C-terminal portion of mutant ataxin-3 that includes the polyglutamine stretch is more toxic than the entire protein, in cell and animal models (Ikeda et al., 1996; Paulson et al., 1997; Warrick et al., 1998; Yoshizawa et al., 2000; Hara et al., 2001; Goti et al., 2004). Thus, selective neuronal loss in MJD/SCA3 was proposed to stem from a toxic cleavage fragment of mutant ataxin-3 (Ikeda et al., 1996). Indeed, a mutant ataxin-3 putative-cleavage fragment was identified in transfected cell lines (Yamamoto et al., 2001; Berke et al., 2004). We provided the first evidence of such fragment in brain of an MJD/SCA3-like mouse model and postmortem MJD/SCA3 patients, and proposed that selective neuronal loss stems from the fragment at a critical nuclear concentration (Goti et al., 2004; Colomer Gould et al., 2006). The toxic fragment is proposed to aggregate, recruit other proteins including normal ataxin-3, and seed the formation of intranuclear inclusions (Paulson et al., 1997; Li et al., 2002; Donaldson et al., 2003; Kobayashi and Kakizuka, 2003; Warrick et al., 2005). Indeed, a C-terminal portion of mutant ataxin-3 but not the full-length protein is reported to change the conformation of normal ataxin-3 (Haacke et al., 2006).

Identifying cleavage site(s) in human mutant ataxin-3 could contribute to understanding the mechanism of proteolysis involved and reveal candidate targets for therapy. Based on studies using cell and in vitro models, mutant ataxin-3 has been proposed to have proteolytic site(s) at amino acid(s) 241–248 (Berke et al., 2004), 250 (Haacke et al., 2006), 286 (Yoshizawa et al., 2000), within amino acids 191–342 (Mauri et al., 2006), and recently around amino acids 60, 200, or 260 (Haacke et al., 2007). Using a mouse model, we narrowed a cleavage site in mutant ataxin-3 to the N-terminus of amino acid 221 (Goti et al., 2004). Here, we expressed mutant ataxin-3 with amino acids 190–220 deleted in neuroblastoma cells and in transgenic mice. Mutant ataxin-3 fragments were lacking in the cell but not the mouse model. Based on the results obtained in the mouse model, we narrowed the proteolytic site in mutant ataxin-3 to the N-terminus of amino acid 190.

Materials and methods

Delta Q20 and Q71 cDNA constructs

Deletion of nucleotides #603 to 695 (amino acids 190–220) in mjd1a cDNA (Kawaguchi et al., 1994) were made with two sets of PCR reactions by using Platinum Pfx DNA polymerase kit (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA), and the following templates and primers [the nucleotide numbers on the primers are according to the reported sequence for mjd1a cDNA (Kawaguchi et al., 1994)]. The templates were human ataxin-3 mjd1a Q20 or Q71 cDNA in pBluescript, a gift from Dr. Akira Kakizuka, Laboratory of Functional Biology, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan (Kawaguchi et al., 1994). In one reaction, the sense primer including BamH1 restriction site (bold), start codon (underlined), and nucleotides 36–59 was 5′GGCGGGGATCCATGGAGTCCATCTTCCACGAGAAA3′, the antisense primer with EcoRV and SfoI restriction site (bold), and nucleotides 583–602 was 5′GTTCGGATATCTGGCGCCTGGTCGATGCATCTGTTGGA3′. In the second PCR reaction, the sense primer with SfoI restriction site (bold) and nucleotides 696–719 was 5′GATAGGCGCCATGTTAGACGAAGATGAGGAGGAT3′, the antisense primer with an EcoRV restriction site (bold), a stop codon (underlined), and nucleotides 1097–1118 was 5′CGGCGATATCTTATGTCAGATAAAGTGTGAAG3′. The PCR settings were 94 °C for 5 min and 30 cycles of: 94 °C for 15 sec, 56 °C for 45 sec, 68 °C for 1 min per kb. PCR products were purified with Qiagen QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA). The first PCR reaction product and vector pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) were digested with BamH1 and EcoRV and ligated. The resulting construct and the second PCR product (with Q20 or Q71) were digested with SfoI and EcoRV and ligated. The resulting deletion constructs Q20 or Q71 delta190–220 are missing amino acids 190-KLIGEELAQLKEQRVHKTDLERMLEANDGSG-220 and were used in the proteasome inhibition assay described below. To add the 3′-untranslated sequence of mjd1a cDNA, the BamH1-PpuM1 portion of the deletion constructs (containing start codon, deletion, and repeats) were extracted and substituted for the BamH1-PpuM1 portion (containing start codon and repeats) of mjd1a cDNA in the modified pcDNA3 vector (lacking NotI, and with two XhoI flanking the cloning sites) previously described (Goti et al., 2004). Each resulting construct contained an XhoI-XhoI insert that was subcloned into the XhoI cloning site of the mouse prion promoter vector, MoPrP.Xho, as described previously (Goti et al., 2004); the MoPrP.Xho vector was a gift from Dr. David Borchelt, Department of Neuroscience, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL. The constructs were confirmed to be correct by Western blot analysis of lysates from transfected HEK293 cells, and nucleotide sequencing by following procedures reported previously (Goti et al., 2004).

Proteasome inhibition

Neuroblastoma cells, Neuro2a, were transfected as described (Goti et al., 2004), and permanent clones were selected in complete medium with 200 μg/ml of G418 or neomycin (BD Biosciences Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). The clones were incubated in the presence or absence of proteasome inhibitor MG132 essentially as described (Lunkes et al., 2002), with some modifications. Briefly, 50% confluent Neuro-2a cells (permanently transfected and controls) were incubated for 48 hours with 5 μM MG132 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, cat# C2211) prepared in DMSO. After treatment, cells were detached by gentle scraping, transferred to 2-ml tubes, and centrifuged for 5 minutes at 700 × g, 4°C. The pellets were suspended by gentle vortexing in 150 μl of buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100) containing protease inhibitors (Complete™, Roche, Indianapolis, IN), and stored at −20°C until used for Western blot analysis.

Transgenic mice

The transgene constructs were prepared for zygote injection as described (Goti et al., 2004) and injected into the male pronucleus of fertilized oocytes from C57BL/6J×C3H/HeJ mice, which were implanted into pseudopregnant mice. Transgenic mice were identified by a standard three-way PCR assay of mouse-tail genomic DNA as described (Goti et al., 2004). They were set up for breeding at 5 weeks of age with B6C3HJ1 wild type mice for hemizygous offspring or with hemizygotes for homozygous offspring. The level transgenic protein in brain was established by western blot analysis using ataxin-3-his antibody as described below.

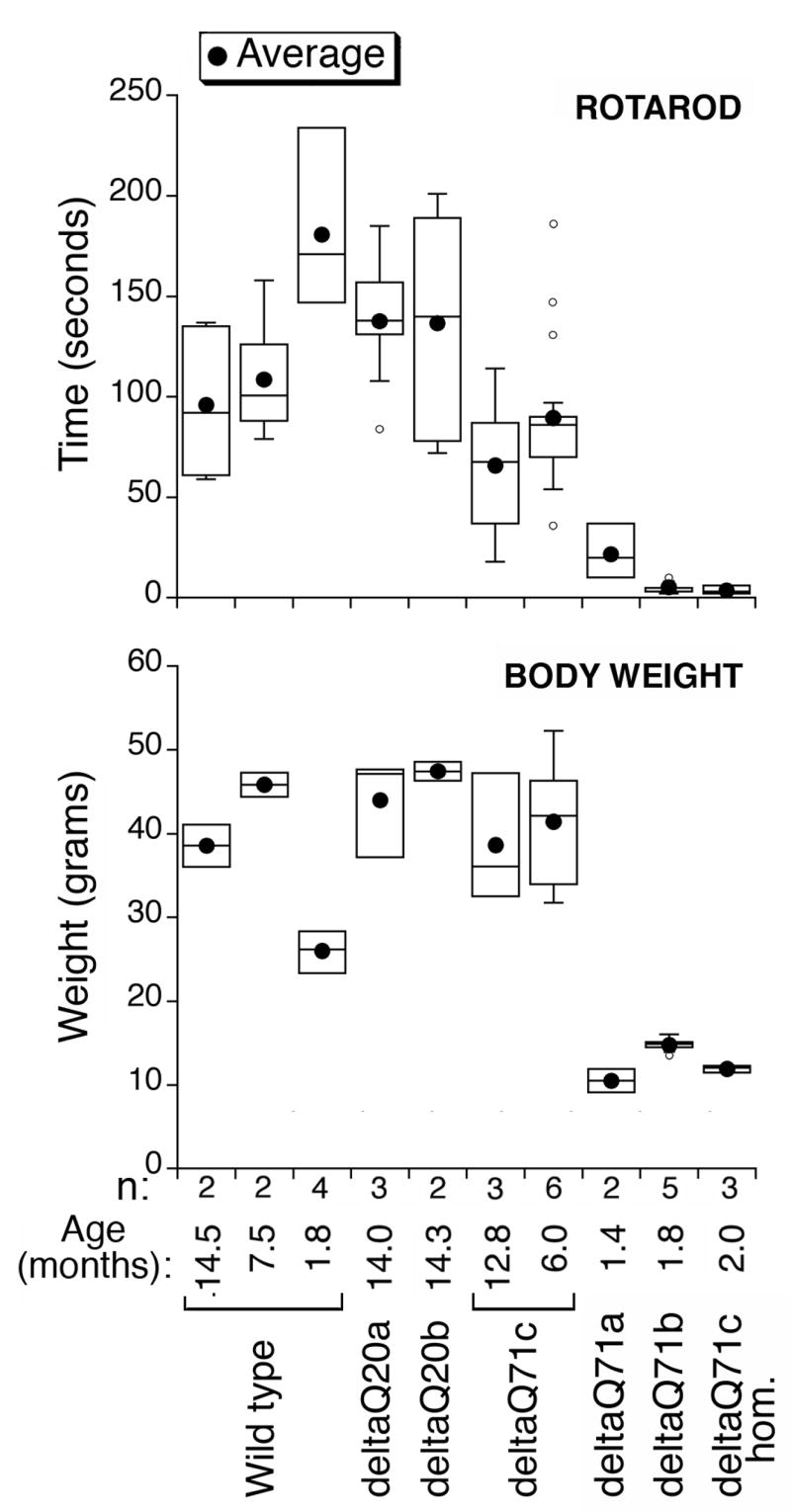

Signs and behavior

To establish age at death, a cohort of up to 23 animals per line were kept for a maximum of 15 months. Two to six males of the same age were used for weight measurements, and placed on a RotaRod to establish the seconds the animals could run on an accelerating rod. The RotaRod test was performed as described previously (Goti et al., 2004). The data collected for each group of animals was represented in a box plot using KaleidaGraph v3.6, Synergy Software, Reading, PA.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis of cell lysates or mouse brain homogenates were performed as described previously (Goti et al., 2004). The mouse monoclonal antibodies used are 1H9 to amino acids 221–224 (Chemicon International Inc, Temecula, CA) (Goti et al., 2004) and 1C2 to the polyglutamine expansion (Chemicon), both at 1:500. The rabbit polyclonal to ataxin-3 his-tagged and lacking amino acids 64–78 was used at 1:4000; it was a gift from Dr. Henry Paulson (Department of Neurology, University of Iowa College of Medicine, Iowa City, IA) (Paulson et al., 1997). Two new rabbit polyclonal antibodies were prepared: 241/242 to amino acids 1–80 and 80441 to amino acids 260–271, both used at 1:2000. The amino acid numbers correspond to the reported sequence for mjd1a (Kawaguchi et al., 1994).

Preparation of antibody 80441

A multi-antigenic peptide was synthesized and used as immunogen in rabbits by Invitrogen Corporation (Carlsbad, CA). The immunoglobulin-fraction was isolated from the resulting serum by ammonium sulfate precipitation according to manufacturer’s procedure (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The immunoglobulin fraction pre-incubated with or without the corresponding peptide at 20 μg/ml were tested on Western blots of transgenic or wild type mouse brain homogenates. The immunoreactivity to ataxin-3 was inhibited by the peptide (not shown).

Preparation of antibody to 241/242

An alternative splicing isoform of mutant ataxin-3 mjd1a with a stop codon after amino acid 80 was isolated from patient lymphoblasts (unpublished results), and subcloned into a pGEX-4T2 vector as described (Goti et al., 2004). The resulting GST-amino acids 1–80 fusion protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE, which was stained with Coomassie dye. The corresponding band was extracted and sent to Invitrogen to be used as immunogen in rabbits. The immunoglobulin fraction of the resulting serum was isolated as above, and pre-adsorbed with GST by affinity chromatography as described (Goti et al., 2004).

Results

Our previously described transgenic mice expressing human mutant ataxin-3 mjd1a under control of the mouse prion promoter were named Q71-B and Q71-C homozygotes (Goti et al., 2004). They had a phenotype that resembles MJD/SCA3 including trembling, progressive movement coordination problems, weight loss, and premature death. These Q71 transgenic mice had a mutant ataxin-3 fragment in brain that resulted from processing at a site N-terminal to amino acid 221 (Goti et al., 2004). To establish whether processing occurs within amino acids 190–220, we generated human mutant ataxin-3 mjd1a lacking these amino acids (Fig. 1). We named such construct deltaQ71, expressed it first in a neuroblastoma cell line and next in transgenic mice.

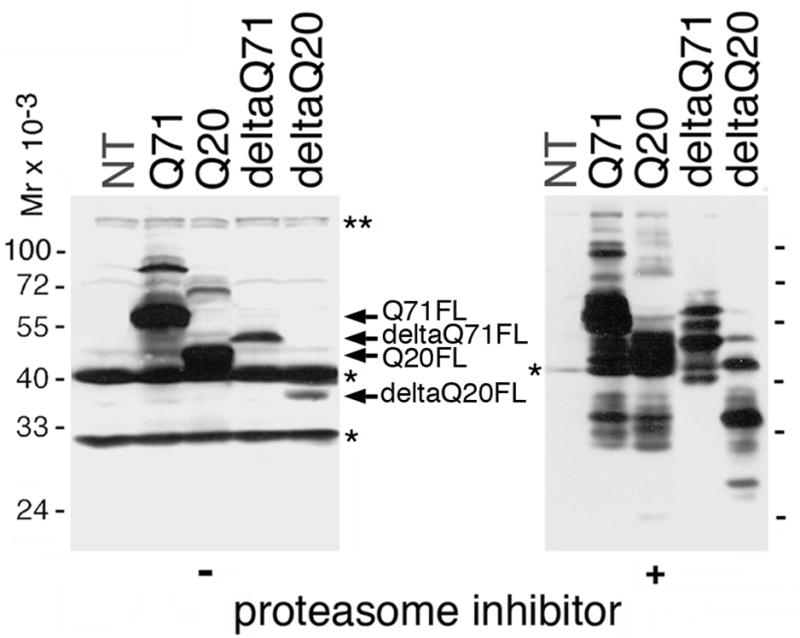

Transfected cells expressing mutant ataxin-3 mjd1a lacking amino acids 190–220

We expressed deltaQ71 in a neuroblastoma murine cell line, Neuro2a. For comparison, we also expressed in Neuro2a cells human mutant (Q71) or normal (Q20) ataxin-3 mjd1a without the deletion, and human normal ataxin-3 mjd1a with amino acids 190–220 deleted (deltaQ20). We subjected the resulting cell lysates to Western blotting with the antibody to ataxin-3-his. As expected, due to the deletion, the full-length forms of the deltaQ71 and deltaQ20 were smaller than those of Q71 and Q20, respectively (FL, Fig. 2 left blot). No putative cleavage fragments of Q71, Q20, deltaQ71, or deltaQ20 were detected (Fig. 2, left blot).

Fig. 2.

Expression of deltaQ71 or controls in transfected neuroblastoma cells. Western blot analysis of lysates from Neuro2a cells untransfected (NT) or permanently transfected expressing the indicated proteins. The cells were untreated (−) or treated (+) with the proteasome inhibitor MG132. The same amount of total protein was loaded per sample. The blot was revealed using an antibody to ataxin-3-his, which was generated using most of ataxin-3 (Paulson et al., 1997). Like untransfected cells, all lysates have murine ataxin-3 full-length form and possible fragment (*) that are readily visible on the (−) blot but not the (+) blot because a longer exposure is shown. The full-length form (FL) of Q71, deltaQ71, Q20, and deltaQ20 (arrows) are highlighted in the (−) blot. In the (+) blot, the band pattern is too complex to highlight specific bands accurately but clearly less fragments are detected for deltaQ71 than Q71, Q20, or deltaQ20.

To allow scarce fragments to accumulate, we reduced their degradation by treating the transfected cells with a proteasome inhibitor as described (Lunkes et al., 2002). We subjected the resulting cell lysates to Western blot analysis revealed with the antibody to ataxin-3-his. Several bands larger and smaller than the full-length form of Q71, Q20, deltaQ71, and deltaQ20 were detected (Fig. 2, right blot). DeltaQ71 fragments were lacking compared to Q71, Q20, or deltaQ20 (Fig 2) suggesting that the deletion removed a cleavage site(s).

Transgenic mice expressing mutant ataxin-3 mjd1a lacking amino acids 190–220

To determine whether the above cell model recapitulated the proteolysis of mutant ataxin-3 occurring in brain, we expressed the deltaQ71 in a mouse model. We generated transgenic mice expressing deltaQ71 or deltaQ20 under the control of the mouse prion promoter. Approximately 30 founders for each deltaQ71 and deltaQ20 were identified by tail genomic PCR. Two deltaQ20 founders were used to generate lines a and b. The deltaQ71 founders were either infertile (not included in this report) or fertile. The fertile founders had either infertile offspring (deltaQ71a and deltaQ71b hemizygotes) or fertile offspring that were used to develop a line (deltaQ71c hemizygotes). These hemizygotes were inbred to continuously generate deltaQ71c homozygotes; which were infertile. The transgenic construct in the deltaQ20 and deltaQ71 hemizygous lines had a stable transmission in multiple generations with a predictive frequency of about 50%. In brief, we include results from the following representative transgenic mice: deltaQ20a and deltaQ20b hemizygotes, hemizygous offspring of mosaic deltaQ71a and deltaQ71b founders, and, deltaQ71c hemizygotes and homozygotes.

Fertile founders with infertile offspring are likely to be mosaic. We previously reported that mutant ataxin-3 damages neuroendocrine cells, resulting in reduced gonadotropic hormone levels in serum and secondary gonadotropic failure (Colomer Gould et al., 2006). Thus, fertile founders with infertile offspring are likely to be mosaic, i.e., the transgenic construct is integrated in the genome of their gametes but not neuroendocrine cells.

Signs and behavior

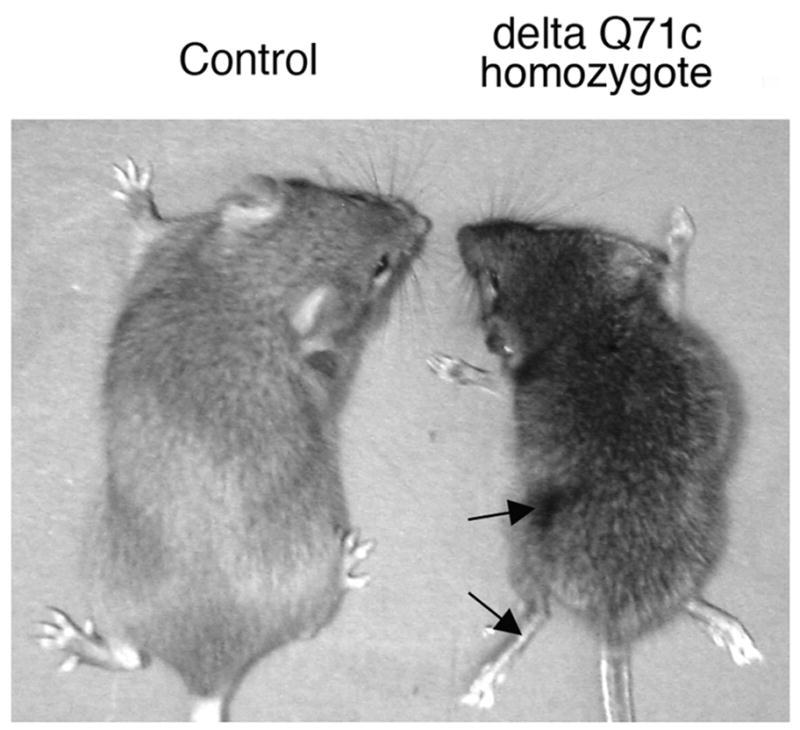

We analyzed the appearance of the transgenic mice. DeltaQ71c homozygotes (Fig. 3), deltaQ71a and deltaQ71b hemizygotes (not shown) had a progressively abnormal appearance including tremor, abnormal posture (hunchback with low pelvic elevation and muscle wasting), and ataxic limbs (clutched paws and uncoordinated extension of theirs limbs). By contrast, deltaQ20 hemizygous lines a (Fig. 3) and b (not shown), and deltaQ71c hemizygotes (not shown) had the appearance of wild type mice.

Fig. 3.

Appearance of deltaQ71 transgenic mice and controls. Representative picture of a deltaQ71c homozygote, and deltaQ20a hemizygote (Control). They were both females at 2.5 months of age. The Control had the appearance of wild type mice. The deltaQ71c homozygote had atrophied paws and muscle wasting (arrows).

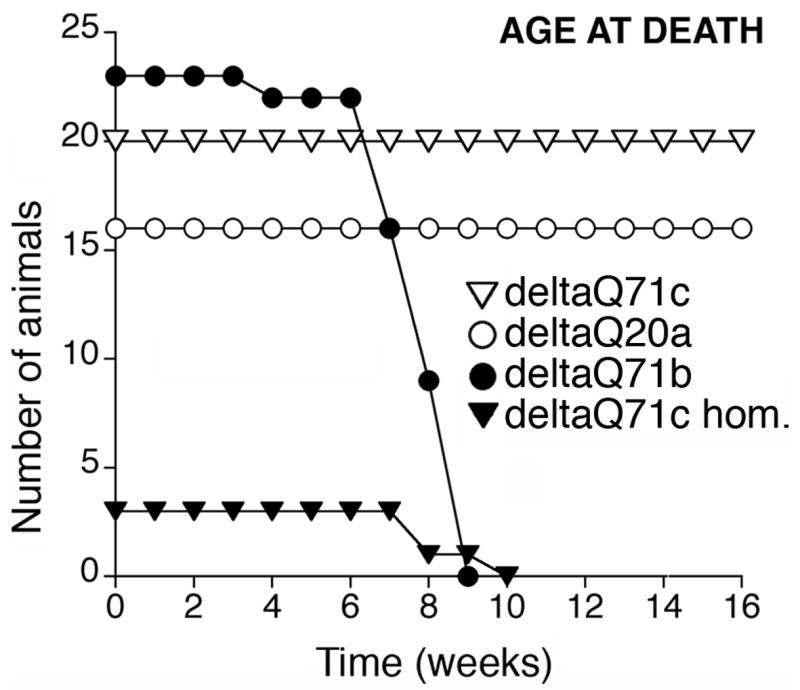

We determined the movement coordination ability, body weight, and age at death of the transgenic mice. The deltaQ71 transgenic mice with an abnormal appearance also had progressive unsteady gait and movement coordination problems, which was documented at a late stage by the RotaRod test (Fig. 4). They had weight loss (Fig. 4) and premature death (Fig. 5). DeltaQ71a hemizygotes died at 1.4 ± 0.2 months of age (not represented in Fig. 5), deltaQ71c homozygotes died at 2.16 ± 0.28 months, and delta Q71b hemizygotes died at 2 ± 0.29 months of age (Fig. 5).

Fig 4.

Movement coordination and body weight of deltaQ71 transgenic mice and controls. The indicated number (n) of male wild type or transgenic mice at the age listed were subjected to weight measurements and the rotarod test. The values obtained for a given group of males on different trials of these tests and on consecutive days were pooled and represented in a box plot using KaleidaGraph. The black circle represents the average, the line dividing the box the median, one-fourth of the data falls between the bottom of the box and the median, and another one-fourth between the median and the top of the box. The lines attached to the box extend to the smallest and the largest data values. Outliers are indicated as small circles and defined as values smaller than the lower quartile minus 1.5 times the interquartile range, or larger than the upper quartile plus 1.5 times the interquartile range. DeltaQ20a, deltaQ20b, and deltaQ71c hemizygotes had the body weight and rotarod performance of wild type mice. DeltaQ71c homozygotes (deltaQ71c hom), deltaQ71a and deltaQ71b hemizygotes had weight loss, and a poor performance in the rotarod test possibly due to movement coordination problems.

Fig. 5.

Age at death of deltaQ71transgenic mice and controls. Cohorts of the indicated number of transgenic mice were used. Like wild type mice, deltaQ20a and deltaQ71c hemizygotes did not undergo premature death. DeltaQ71c homozygotes (deltaQ71c hom), and deltaQ71b hemizygotes died prematurely.

By contrast the transgenic mice with a normal appearance, i.e., deltaQ71c, deltaQ20a, and deltaQ20b hemizygotes were able to run on the RotaRod even at 12–14 months of age (Fig. 4), had no weight loss (Fig. 4) or premature death (Fig. 5). They were euthanized at 15 months of age.

Since a similar phenotype was observed in offspring from three deltaQ71 founders, the phenotype is caused by the transgene not by an altered expression of the genes flanking the site of transgene integration. The abnormal signs and behavior observed in deltaQ71 transgenic mice are similar to those reported for Q71 transgenic mice and considered MJD/SCA3-like (Goti et al., 2004).

Transgene expression

We established transgene expression in the deltaQ71 and deltaQ20 mice, by subjecting their brain homogenates to Western blotting with the ataxin-3-his antibody. For comparison, we included brain homogenates from wild type mice, and our previously described Q71 and Q20 transgenic mice. Like in wild type mouse brain, all samples had detectable murine ataxin-3 bands (Fig. 6A). DeltaQ20 full-length form was smaller than Q20 full-length form (Fig. 6A). A Q20 but not a deltaQ20 fragment was detected, probably due lower transgenic protein levels. Thus, we could not study the human normal ataxin-3 fragment further

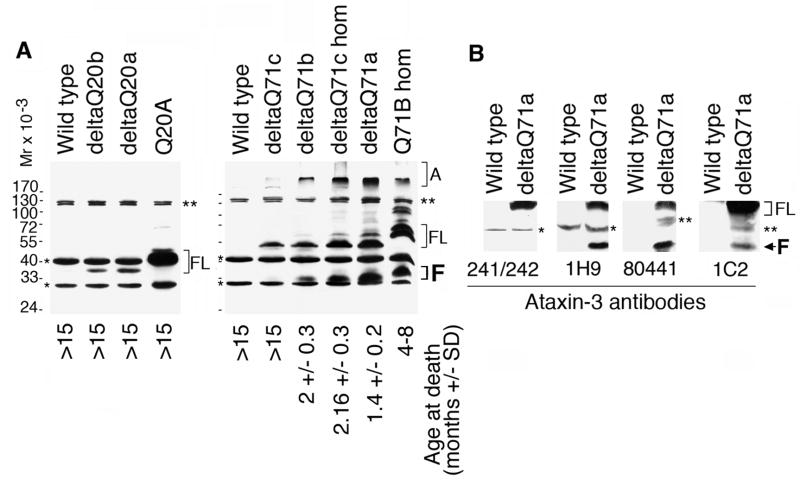

Fig. 6.

A deltaQ71 fragment was detected in brain of transgenic mice.

(A) Western blot analysis of brain homogenates from male wild type mice and the indicated homozygotes (hom) or hemizygotes. The blot was revealed with an antibody to ataxin-3-his. Like wild type brain, all samples had a murine ataxin-3 full-length form and a possible fragment (*) and a higher molecular weight doublet that is possibly nonspecific (**). The full-length form of the transgenic proteins are highlighted (FL). DeltaQ71, like Q71, had also an aggregate (A), and a fragment (F). The aggregate and fragment in deltaQ71c hemizygotes was scarce and only detected in a longer exposure of this blot (not shown). The abundance of transgenic protein in brain tended to be inversely proportional to the age at death (indicated). The animals that did not have premature death are indicated (>15 months).

(B) Western blot analysis of brain homogenates from wild type or deltaQ71a hemizygous males revealed with different ataxin-3 antibodies; the amino acids recognized by each antibody are represented in Fig 1. Murine ataxin-3 full-length form (*) or other minor bands (**) were detected by the indicated antibodies. DeltaQ71 full-length form (FL) reacted with all antibodies, and its fragment (F) reacted with all antibodies except 241/242.

Like Q71, deltaQ71 had three forms: aggregate (A), full-length form (FL), and fragment (F) (Fig. 6A). The deltaQ71 full-length form and fragment were smaller than the corresponding forms of Q71 (Fig. 6A). The aggregate and fragment are visible in the brains of all the deltaQ71 transgenic mice included in Fig 6A, except for deltaQ71c hemizygote, in which they were scarce and detected in a longer exposure of the blot (not shown). The transgenic mice with more abundant deltaQ71 full-length form and especially aggregate and fragment in brain tended to have an earlier age at death (Fig 6A).

Our previously described Q71-B homozygotes had levels of transgenic protein in brain comparable to deltaQ71 animals but died at a later age (Fig 6A) suggesting that the absence of amino acids 190–220 increases mutant ataxin-3 toxicity. The brain distribution of the deltaQ20 and all forms of the deltaQ71 transgenic proteins were comparable to those described previously for Q20 and Q71 transgenic proteins (not shown). They were detected throughout the brain. The deltaQ71 aggregate and fragment were more abundant in cerebellum than other brain regions such as cerebral cortex; the former is severely affected and the latter is typically spared in MJD/SCA3 patients.

Mutant ataxin-3 fragment

To determine whether deltaQ71 was processed at the N- or C-terminal end of the deletion, we studied the immunoreactivity of the deltaQ71 fragment to different ataxin-3 specific antibodies. We subjected brain homogenates from deltaQ71a hemizygotes to Western blotting with antibodies to amino acids 1–80, 221–224, 260–271, or to the polyglutamine expansion (Fig. 1). The delta Q71 fragment reacted with antibodies to amino acids 221–224, 260–271, and the polyglutamine expansion, but not 1–80 (Fig. 6B). Thus, the deltaQ71 fragment contained epitopes C-terminal to amino acid 220. The deltaQ71 fragment was smaller than the Q71 fragment indicating that it includes amino acids N-terminal to the deletion. Taken together, these results indicate that deltaQ71 is cleaved at a site N-terminal to amino acid 190.

Discussion

Previously, we generated transgenic mice expressing human mutant (Q71) or normal (Q20) ataxin-3 mjd1a under the control of the mouse prion promoter. Q71 transgenic mice expressing mutant ataxin-3 above a critical level developed a phenotype similar to MJD/SCA3 including progressive movement coordination problems, weight loss, and premature death. Q20 transgenic mice had a normal behavior. A mutant ataxin-3 fragment was detected in Q71 brain that contained epitopes C-terminal to amino acid 220 (Goti et al., 2004). Here, we generated and characterized transgenic mice expressing human mutant (deltaQ71) or normal (deltaQ20) ataxin-3 mjd1a lacking amino acids 190–220. Their signs and behavior were comparable to those of Q71 or Q20 transgenic mice, respectively, except that with similar levels of transgenic protein in brain the deltaQ71 died younger than Q71-B homozygotes. We conclude that amino acids 190–220 in mutant ataxin-3 are not essential for the protein to cause an MJD/SCA3-like phenotype but might have a role in reducing the toxicity of the protein, possibly by interacting with other proteins. The mutant ataxin-3 fragment detected in brain of deltaQ71 transgenic mice is smaller that the fragment reported in brain of Q71 transgenic mice; both fragments contain epitopes C-terminal to amino acid 220 and lack epitopes within amino acids 1–80. We conclude that amino acids 190–220 in mutant ataxin-3 lack an active putative cleavage site and narrow the position of the active site to the N-terminus of amino acid 190.

As observed in Q71 transgenic mice, in the deltaQ71 transgenic mice the putative cleavage fragment was readily detectable in brain homogenates of animals with an MJD/SCA3-like phenotype (e.g. deltaQ71c homozygotes) and barely detectable in brain of normal deltaQ71 transgenic mice (deltaQ71c hemizygotes) (Fig. 6A). By contrast, the deltaQ71 full-length form was readily detectable in the brain homogenate of all animals (Fig. 6A). These results support the toxic fragment hypothesis described in Introduction. These results are also consistent with our previous hypothesis that MJD/SCA3 pathogenesis is associated with a critical concentration of the putative cleavage fragment and suggest that decreasing mutant ataxin-3 expression or fragment abundance below a critical level might eliminate the disease (Goti et al., 2004; Colomer Gould et al., 2006).

Using cell or in vitro models, human mutant ataxin-3 is proposed to have potential cleavage site(s) within amino acids 241–248 (Berke et al., 2004), 250 (Haacke et al., 2006), 269–286 (Yoshizawa et al., 2000), and around amino acids 60, 200, 260 (Haacke et al., 2007); autolytic cleavage of normal ataxin-3 within amino acids 191–342 is proposed to occur in the disease protein (Mauri et al., 2006). The deltaQ71 fragments that we detected in transfected cells (Fig. 2 and unpublished results using transfected COS 7 cells), and transgenic mouse brain (Fig. 6) were not comparable. The size variations between our samples are not artifacts generated during the preparation of the sample; as reported for ataxin-3 in other experimental systems (Chow et al., 2006). Taken together, our results emphasize the importance of using an animal model to confirm the results obtained in a cell model regarding mutant ataxin-3 proteolysis.

Multiple proteolytic processing is proposed for a polyglutamine disease proteins, huntingtin (DiFiglia et al., 1997; Li et al., 2000; Wheeler et al., 2000; Kim et al., 2001; Mende-Mueller et al., 2001; Gafni and Ellerby, 2002; Lunkes et al., 2002; Sun et al., 2002; Wellington et al., 2002; Gafni et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2006; Tanaka et al., 2006) and atrophin (Ellerby et al., 1999; Schilling et al., 1999). The sequential or concomitant events include: a) caspase processing (Thornberry and Lazebnik, 1998) of the disease protein, in the cytoplasm; b) processing of the resulting fragment by other proteolytic ezymes [calpains, pepstatin-sensitive aspartic endopeptidases such as cathepsin D, and/or an unknown enzyme(s)]; and c) accumulation of the smaller proteolytic product(s) in the nucleus of neurons. A recent report strengthened this hypothesis; a mouse model expressing huntingtin resistant to caspase 6 cleavage lacked the corresponding proteolytic product in brain homogenates, abnormal behavior, neurodegeneration, and had a delayed nuclear localization of the disease protein in neurons (Graham et al., 2006).

Similarly, multiple sequential or concomitant proteolytic processing events could precede or follow the formation of the mutant ataxin-3 fragment detected in nuclear fractions of brains from MJD/SCA3 transgenic mice and postmortem patients (Goti et al., 2004). Mutant ataxin-3 has potential caspase sites that are N-terminal to amino acid 190, at amino acids 142–145 and 168–171 (Wellington et al., 1998). However, the fragment in Q71 homozygote brain was smaller than truncations of mutant ataxin-3 missing amino acids 1–145 or 1–171 (Goti et al., 2004). Calpain sensitive sites were detected in ataxin-3 around amino acid 200 (Haacke et al., 2007) but we detected the fragment in brain of transgenic mice even in the absence of amino acids 190–220. Thus, we speculate that the mutant ataxin-3 fragment that we detected in Q71 and deltaQ71 transgenic mouse brain might not be a caspase or calpain product. This fragment’s formation could be preceded or followed by caspase or calpain proteolysis. We have not found smaller fragments in Q71 brain that could result from processing at the C-terminus of amino acid 190; however, such fragment(s) are predicted to be SDS insoluble (Haacke et al., 2006) and in our gel system they might co-migrate with the aggregate (Fig 6A). This speculative model of mutant ataxin-3 proteolysis in brain cells is based on calpain and caspase sites, and aggregation properties of ataxin-3, identified using in vitro and cell model assays. Thus, more studies in brain cells are needed to establish whether the Q71 and deltaQ71 fragments are a product of a calpain, caspase or a novel enzyme.

In summary, based on results obtained in a mouse model we narrowed the site of mutant ataxin-3 mjd1a putative proteolysis to amino acids N-terminal to residue 190, probably within amino acids 80–190. The proteolytic enzyme(s) processing mutant ataxin-3 could be an ideal target for therapy of MJD/SCA3.

Acknowledgments

We especially thank: a) Debbie Swing for performing the zygote injections; b) Mrs. Mary Keyser and Suzanne Fowble for budget administration; and c) Dr. Pamela Talalay for critical editing of the manuscript. This work was supported by: a) Donation from JCG (VCG); b) NIH grant NS42731-01 (VCG); c) AHA grant EIG 0140166N (VCG); and in part by, d) NIH Intramural Research Program, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research (NAJ, NGC).

Abbreviations

- MJD

Machado-Joseph disease

- SCA3

spinocerebellar ataxia type 3

- Q71

human mutant ataxin-3 with a 71 polyglutamine stretch

- Q20

human ataxin-3 with a 20 polyglutamine stretch

- deltaQ71

Q71 lacking amino acids 190–220

- deltaQ20

Q20 lacking amino acids 190–220

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Berke SJ, Schmied FA, Brunt ER, Ellerby LM, Paulson HL. Caspase-mediated proteolysis of the polyglutamine disease protein ataxin-3. J Neurochem. 2004;89:908–918. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett B, Li F, Pittman RN. The polyglutamine neurodegenerative protein ataxin-3 binds polyubiquitylated proteins and has ubiquitin protease activity. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:3195–3205. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow MK, Ellisdon AM, Cabrita LD, Bottomley SP. Purification of polyglutamine proteins. Methods Enzymol. 2006;413:1–19. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)13001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow MK, Mackay JP, Whisstock JC, Scanlon MJ, Bottomley SP. Structural and functional analysis of the Josephin domain of the polyglutamine protein ataxin-3. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;322:387–394. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.07.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colomer Gould VF, Goti D, Kiluk J. A neuroendocrine dysfunction, not testicular mutant ataxin-3 cleavage fragment or aggregate, causes cell death in testes of transgenic mice. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:524–526. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFiglia M, Sapp E, Chase KO, Davies SW, Bates GP, Vonsattel JP, Aronin N. Aggregation of huntingtin in neuronal intranuclear inclusions and dystrophic neurites in brain. Science. 1997;277:1990–1993. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5334.1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson KM, Li W, Ching KA, Batalov S, Tsai CC, Joazeiro CA. Ubiquitin-mediated sequestration of normal cellular proteins into polyglutamine aggregates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8892–8897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530212100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doss-Pepe EW, Stenroos ES, Johnson WG, Madura K. Ataxin-3 interactions with rad23 and valosin-containing protein and its associations with ubiquitin chains and the proteasome are consistent with a role in ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:6469–6483. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.18.6469-6483.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durr A, Stevanin G, Cancel G, Duyckaerts C, Abbas N, Didierjean O, Chneiweiss H, Benomar A, Lyon-Caen O, Julien J, Serdaru M, Penet C, Agid Y, Brice A. Spinocerebellar ataxia 3 and Machado-Joseph disease: clinical, molecular, and neuropathological features. Ann Neurol. 1996;39:490–499. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellerby LM, Andrusiak RL, Wellington CL, Hackam AS, Propp SS, Wood JD, Sharp AH, Margolis RL, Ross CA, Salvesen GS, Hayden MR, Bredesen DE. Cleavage of atrophin-1 at caspase site aspartic acid 109 modulates cytotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8730–8736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler HL. Machado-Joseph-Azorean disease. A ten-year study. Arch Neurol. 1984;41:921–925. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1984.04050200027013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gafni J, Ellerby LM. Calpain activation in Huntington’s disease. J Neurosci. 2002;22:4842–4849. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-12-04842.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gafni J, Hermel E, Young JE, Wellington CL, Hayden MR, Ellerby LM. Inhibition of calpain cleavage of huntingtin reduces toxicity: accumulation of calpain/caspase fragments in the nucleus. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:20211–20220. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401267200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goti D, Katzen SM, Mez J, Kurtis N, Kiluk J, Ben-Haiem L, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Kakizuka A, Sharp AH, Ross CA, Mouton PR, Colomer V. A mutant ataxin-3 putative-cleavage fragment in brains of Machado-Joseph disease patients and transgenic mice is cytotoxic above a critical concentration. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10266–10279. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2734-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham RK, Deng Y, Slow EJ, Haigh B, Bissada N, Lu G, Pearson J, Shehadeh J, Bertram L, Murphy Z, Warby SC, Doty CN, Roy S, Wellington CL, Leavitt BR, Raymond LA, Nicholson DW, Hayden MR. Cleavage at the caspase-6 site is required for neuronal dysfunction and degeneration due to mutant huntingtin. Cell. 2006;125:1179–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haacke A, Broadley SA, Boteva R, Tzvetkov N, Hartl FU, Breuer P. Proteolytic cleavage of polyglutamine-expanded ataxin-3 is critical for aggregation and sequestration of non-expanded ataxin-3. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:555–568. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haacke A, Hartl FU, Breuer P. Calpain inhibition is sufficient to suppress aggregation of polyglutamine-expanded ataxin-3. J Biol Chem. 2007 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611914200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara J, Beuckmann CT, Nambu T, Willie JT, Chemelli RM, Sinton CM, Sugiyama F, Yagami K, Goto K, Yanagisawa M, Sakurai T. Genetic ablation of orexin neurons in mice results in narcolepsy, hypophagia, and obesity. Neuron. 2001;30:345–354. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00293-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa Y, Goto J, Hattori M, Toyoda A, Ishii K, Jeong SY, Hashida H, Masuda N, Ogata K, Kasai F, Hirai M, Maciel P, Rouleau GA, Sakaki Y, Kanazawa I. The genomic structure and expression of MJD, the Machado-Joseph disease gene. J Hum Genet. 2001;46:413–422. doi: 10.1007/s100380170060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda H, Yamaguchi M, Sugai S, Aze Y, Narumiya S, Kakizuka A. Expanded polyglutamine in the Machado-Joseph disease protein induces cell death in vitro and in vivo. Nat Genet. 1996;13:196–202. doi: 10.1038/ng0696-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jardim LB, Silveira I, Pereira ML, Ferro A, Alonso I, do Ceu Moreira M, Mendonca P, Ferreirinha F, Sequeiros J, Giugliani R. A survey of spinocerebellar ataxia in South Brazil - 66 new cases with Machado-Joseph disease, SCA7, SCA8, or unidentified disease-causing mutations. J Neurol. 2001;248:870–876. doi: 10.1007/s004150170072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi Y, Okamoto T, Taniwaki M, Aizawa M, Inoue M, Katayama S, Kawakami H, Nakamura S, Nishimura M, Akiguchi I, et al. CAG expansions in a novel gene for Machado-Joseph disease at chromosome 14q32.1. Nat Genet. 1994;8:221–228. doi: 10.1038/ng1194-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YJ, Sapp E, Cuiffo BG, Sobin L, Yoder J, Kegel KB, Qin ZH, Detloff P, Aronin N, DiFiglia M. Lysosomal proteases are involved in generation of N-terminal huntingtin fragments. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;22:346–356. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YJ, Yi Y, Sapp E, Wang Y, Cuiffo B, Kegel KB, Qin ZH, Aronin N, DiFiglia M. Caspase 3-cleaved N-terminal fragments of wild-type and mutant huntingtin are present in normal and Huntington’s disease brains, associate with membranes, and undergo calpain-dependent proteolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:12784–12789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221451398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Kakizuka A. Molecular analyses of Machado-Joseph disease. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2003;100:261–275. doi: 10.1159/000072862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Macfarlan T, Pittman RN, Chakravarti D. Ataxin-3 is a histone-binding protein with two independent transcriptional corepressor activities. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:45004–45012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205259200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Li SH, Johnston H, Shelbourne PF, Li XJ. Amino-terminal fragments of mutant huntingtin show selective accumulation in striatal neurons and synaptic toxicity. Nat Genet. 2000;25:385–389. doi: 10.1038/78054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunkes A, Lindenberg KS, Ben-Haiem L, Weber C, Devys D, Landwehrmeyer GB, Mandel JL, Trottier Y. Proteases acting on mutant huntingtin generate cleaved products that differentially build up cytoplasmic and nuclear inclusions. Mol Cell. 2002;10:259–269. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00602-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Y, Senic-Matuglia F, Di Fiore PP, Polo S, Hodsdon ME, De Camilli P. Deubiquitinating function of ataxin-3: insights from the solution structure of the Josephin domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:12700–12705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506344102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matilla T, McCall A, Subramony SH, Zoghbi HY. Molecular and clinical correlations in spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 and Machado-Joseph disease. Ann Neurol. 1995;38:68–72. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauri PL, Riva M, Ambu D, De Palma A, Secundo F, Benazzi L, Valtorta M, Tortora P, Fusi P. Ataxin-3 is subject to autolytic cleavage. Febs J. 2006;273:4277–4286. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mende-Mueller LM, Toneff T, Hwang SR, Chesselet MF, Hook VY. Tissue-specific proteolysis of Huntingtin (htt) in human brain: evidence of enhanced levels of N- and C-terminal htt fragments in Huntington’s disease striatum. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1830–1837. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-01830.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SL, Malotky E, O’Bryan JP. Analysis of the role of ubiquitin-interacting motifs in ubiquitin binding and ubiquitylation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:33528–33537. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313097200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicastro G, Menon RP, Masino L, Knowles PP, McDonald NQ, Pastore A. The solution structure of the Josephin domain of ataxin-3: structural determinants for molecular recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10493–10498. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501732102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama K, Murayama S, Goto J, Watanabe M, Hashida H, Katayama S, Nomura Y, Nakamura S, Kanazawa I. Regional and cellular expression of the Machado-Joseph disease gene in brains of normal and affected individuals. Ann Neurol. 1996;40:776–781. doi: 10.1002/ana.410400514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson HL, Das SS, Crino PB, Perez MK, Patel SC, Gotsdiner D, Fischbeck KH, Pittman RN. Machado-Joseph disease gene product is a cytoplasmic protein widely expressed in brain. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:453–462. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson HL, Perez MK, Trottier Y, Trojanowski JQ, Subramony SH, Das SS, Vig P, Mandel JL, Fischbeck KH, Pittman RN. Intranuclear inclusions of expanded polyglutamine protein in spinocerebellar ataxia type 3. Neuron. 1997;19:333–344. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80943-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CA. When more is less: pathogenesis of glutamine repeat neurodegenerative diseases. Neuron. 1995;15:493–496. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90138-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheel H, Tomiuk S, Hofmann K. Elucidation of ataxin-3 and ataxin-7 function by integrative bioinformatics. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:2845–2852. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling G, Wood JD, Duan K, Slunt HH, Gonzales V, Yamada M, Cooper JK, Margolis RL, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Takahashi H, Tsuji S, Price DL, Borchelt DR, Ross CA. Nuclear accumulation of truncated atrophin-1 fragments in a transgenic mouse model of DRPLA. Neuron. 1999;24:275–286. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80839-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt T, Landwehrmeyer GB, Schmitt I, Trottier Y, Auburger G, Laccone F, Klockgether T, Volpel M, Epplen JT, Schols L, Riess O. An isoform of ataxin-3 accumulates in the nucleus of neuronal cells in affected brain regions of SCA3 patients. Brain Pathol. 1998;8:669–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1998.tb00193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schols L, Amoiridis G, Langkafel M, Buttner T, Przuntek H, Riess O, Vieira-Saecker AM, Epplen JT. Machado-Joseph disease mutations as the genetic basis of most spinocerebellar ataxias in Germany [letter] J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995;59:449–450. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.59.4.449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira I, Coutinho P, Maciel P, Gaspar C, Hayes S, Dias A, Guimaraes J, Loureiro L, Sequeiros J, Rouleau GA. Analysis of SCA1, DRPLA, MJD, SCA2, and SCA6 CAG repeats in 48 Portuguese ataxia families. Am J Med Genet. 1998;81:134–138. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19980328)81:2<134::aid-ajmg3>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudarsky L, Coutinho P. Machado-Joseph disease. Clin Neurosci. 1995;3:17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun B, Fan W, Balciunas A, Cooper JK, Bitan G, Steavenson S, Denis PE, Young Y, Adler B, Daugherty L, Manoukian R, Elliott G, Shen W, Talvenheimo J, Teplow DB, Haniu M, Haldankar R, Wypych J, Ross CA, Citron M, Richards WG. Polyglutamine repeat length-dependent proteolysis of huntingtin. Neurobiol Dis. 2002;11:111–122. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y, Igarashi S, Nakamura M, Gafni J, Torcassi C, Schilling G, Crippen D, Wood JD, Sawa A, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Borchelt DR, Ross CA, Ellerby LM. Progressive phenotype and nuclear accumulation of an amino-terminal cleavage fragment in a transgenic mouse model with inducible expression of full-length mutant huntingtin. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;21:381–391. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry NA, Lazebnik Y. Caspases: enemies within. Science. 1998;281:1312–1316. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trottier Y, Cancel G, An-Gourfinkel I, Lutz Y, Weber C, Brice A, Hirsch E, Mandel JL. Heterogeneous intracellular localization and expression of ataxin-3. Neurobiol Dis. 1998;5:335–347. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1998.0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Alfen N, Sinke RJ, Zwarts MJ, Gabreels-Festen A, Praamstra P, Kremer BP, Horstink MW. Intermediate CAG repeat lengths (53,54) for MJD/SCA3 are associated with an abnormal phenotype. Ann Neurol. 2001;49:805–807. doi: 10.1002/ana.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Ide K, Nukina N, Goto J, Ichikawa Y, Uchida K, Sakamoto T, Kanazawa I. Machado-Joseph disease gene product identified in lymphocytes and brain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;233:476–479. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warrick JM, Morabito LM, Bilen J, Gordesky-Gold B, Faust LZ, Paulson HL, Bonini NM. Ataxin-3 suppresses polyglutamine neurodegeneration in Drosophila by a ubiquitin-associated mechanism. Mol Cell. 2005;18:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warrick JM, Paulson HL, Gray-Board GL, Bui QT, Fischbeck KH, Pittman RN, Bonini NM. Expanded polyglutamine protein forms nuclear inclusions and causes neural degeneration in Drosophila. Cell. 1998;93:939–949. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellington CL, Ellerby LM, Gutekunst CA, Rogers D, Warby S, Graham RK, Loubser O, van Raamsdonk J, Singaraja R, Yang YZ, Gafni J, Bredesen D, Hersch SM, Leavitt BR, Roy S, Nicholson DW, Hayden MR. Caspase cleavage of mutant huntingtin precedes neurodegeneration in Huntington’s disease. J Neurosci. 2002;22:7862–7872. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-18-07862.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellington CL, Ellerby LM, Hackam AS, Margolis RL, Trifiro MA, Singaraja R, McCutcheon K, Salvesen GS, Propp SS, Bromm M, Rowland KJ, Zhang T, Rasper D, Roy S, Thornberry N, Pinsky L, Kakizuka A, Ross CA, Nicholson DW, Bredesen DE, Hayden MR. Caspase cleavage of gene products associated with triplet expansion disorders generates truncated fragments containing the polyglutamine tract. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:9158–9167. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.9158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler VC, White JK, Gutekunst CA, Vrbanac V, Weaver M, Li XJ, Li SH, Yi H, Vonsattel JP, Gusella JF, Hersch S, Auerbach W, Joyner AL, MacDonald ME. Long glutamine tracts cause nuclear localization of a novel form of huntingtin in medium spiny striatal neurons in HdhQ92 and HdhQ111 knock-in mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:503–513. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.4.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y, Hasegawa H, Tanaka K, Kakizuka A. Isolation of neuronal cells with high processing activity for the Machado-Joseph disease protein. Cell Death Differ. 2001;8:871–873. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizawa T, Yamagishi Y, Koseki N, Goto J, Yoshida H, Shibasaki F, Shoji S, Kanazawa I. Cell cycle arrest enhances the in vitro cellular toxicity of the truncated Machado-Joseph disease gene product with an expanded polyglutamine stretch. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:69–78. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]