Abstract

The transfection activity and physicochemical properties of the dimyristoyl derivatives from three novel series of double-chained tertiary cationic lipids were compared. Two of the derivatives were constructed as isomers with different linkages of the same bis-(2-dimethylaminoethane) polar headgroup and hydrophobic chains to the diaminopropanol backbone, while the third was designed with a hydrophilic region containing only a single ionizable amine group. Such systematic molecular changes offer a great opportunity to delineate factors critical for transfection activity, which in this work include the intramolecular distance between the hydrophobic chains and pH-expandability of the polar headgroup. The physical studies comprised a variety of techniques, including pKa determination, Langmuir monolayer studies, fluorescence anisotropy, gel electrophoresis mobility shift assay, ethidium bromide displacement assay, particle size distribution, and zeta potential. These studies are crucial in the development of lipid-based gene delivery systems with improved efficacy. Physicochemical characterization revealed that a symmetric bivalent pH-expandable polar headgroup in combination with greater intramolecular space between the hydrophobic chains provide for high transfection activity through efficient binding and compaction of pDNA, increased acyl chain fluidity, and high molecular elasticity.

Keywords: Transfection, Cationic lipids, Monolayer studies, Anisotropy, Phase transition, Elasticity

INTRODUCTION

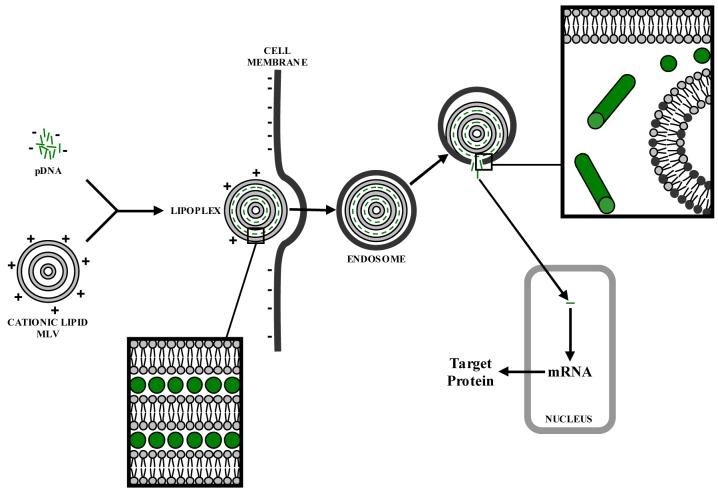

Since the first published report by Felgner and coworkers [1] almost two decades ago on the advent of DOTMA as a carrier of nucleic acids in gene delivery, continuing work on this synthetic lipid [2] and other cationic amphiphiles [3-7] as non-viral vectors is ongoing. To produce efficient gene expression, the cationic lipid must possess suitable structural features that promote effective transfection. This is accomplished by efficient compaction and condensation of DNA by the vector for protection against enzymatic degradation, binding of the cationic liposome-DNA complex (lipoplex) to the cellular surface, internalization of the lipoplex within an endosome, and lipoplex fusion with the endosomal membrane for DNA release into the cytosol where the exogenous genetic material can be translocated to the nucleus for expression of the target gene [8], as illustrated in Figure 1. Membrane fusion has garnered particular attention recently through lipid mixing studies highlighting the fusogenic properties of cationic vesicles as critical for successful transfection [9-11].

Figure 1.

Cationic lipid-mediated transfection in mammalian cells. Cationic liposomes and pDNA spontaneously form lipoplexes with a structure most commonly consisting of nucleic acid monolayers sandwiched between lipid bilayer membranes (inset, bottom left). Lipoplexes are internalized within cells mainly by endocytosis. The acidic endosomal environment promotes membrane fusion and nucleic acids are released into the cytosol (inset, upper right) and imported into the nucleus for target gene expression.

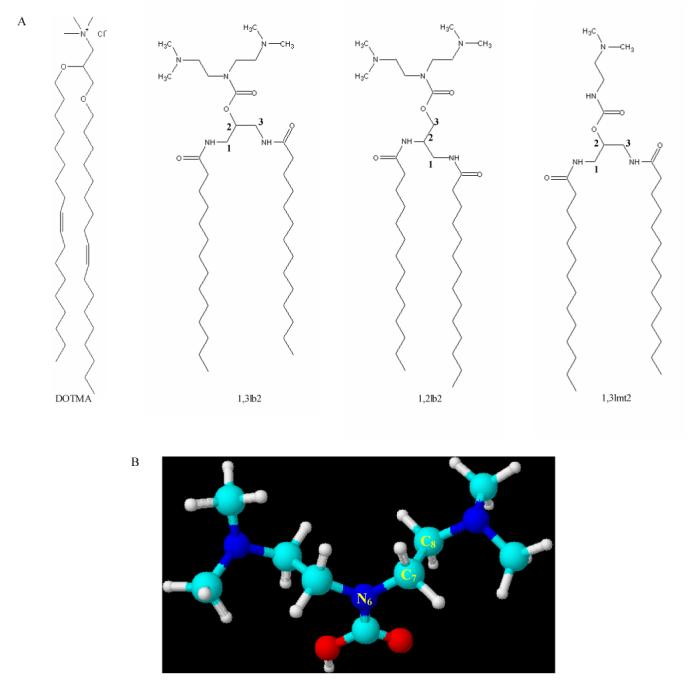

In order to develop cationic lipid-mediated gene delivery systems that are highly potent and minimally toxic, meaningful structure-activity relationships must be generated [12]. Physicochemical characterization is essential in elucidating the structural properties of these surfactants that confer superior lipofection activity. Towards this end, a novel series of asymmetric 1,2-diamino-3-propanol bivalent and symmetric 1,3-dialkoylamido monovalent cationic lipids, designated as 1,2lb and 1,3lmt, respectively, were synthesized and their physicochemical properties in liposomes and complexes with pDNA were correlated with transfection activity [13,14]. In this report a comparison is drawn between the myristoyl derivatives from these series and an isomer of the bivalent derivative containing an attachment of the tertiary amine groups at the 2-position and linkages of the acyl chains at the 1- and 3-positions of the 1,3-diamino-2-propanol backbone (designated as 1,3lb2; Figure 2A). The specific aim of this work is to provide an explanation for the extreme difference in in vitro gene delivery between structurally similar cationic lipid vectors by 1) comparing the physicochemical properties of the aforementioned cytofectins and 2) ascertaining which of these properties induce high transfection activity.

Figure 2.

(A) Molecular structures of N-[1-(2,3-dioleyloxy)propyl]-N,N,N-trimethylammonium chloride (DOTMA) and the dimyristoyl derivatives under investigation. (B) Numbering scheme of the polar headgroup for the computational studies.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

Water for buffer preparation was purified to ∼18 MΩ-cm with a NANOpure ultrapure water system from Barnstead (Dubuque, IA). Tris (hydroxymethyl) aminomethane, 2-(4-morpholino)-ethane sulfonic acid (MES), and ammonium acetate were purchased from Fisher Scientific. Sepharose 4B was purchased from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Piscataway, NJ). Penicillin-streptomycin (10,000 units/ml and 10,000 μg/ml, respectively), EtBr solution (10 mg/ml), and fetal bovine serum were purchased from Invitrogen. Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). 1,2-Dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE) and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, AL). Chloroform was purchased from Mallinckrodt Baker, Inc. (Phillipsburg, NJ). 2-Nitrophenyl β-D-galactopyranoside (ONPG), 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), 2-(p-toluidino) naphthalene-6-sulfonic acid (TNS), 1,6-diphenyl-1,3,5-hexatriene (DPH), and cholesterol were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

1,2-Dimyristoylamidopropane-3-[bis-(2-dimethylaminoethane)] carbamate (1,2lb2) and N,N’-ditetradecanoyl-1,3-diaminopropyl-2-carbamoyl-(N,N-dimethylaminoethane) (1,3lmt2) were synthesized and identified to purity >99%, as described elsewhere [13,14]. The synthetic procedure for the preparation of N,N’-ditetradecanoyl-1,3-diaminopropyl-2-carbamoyl-[bis-(2-dimethylaminoethane)] (1,3lb2) will be published in a different paper. Anal. calcd: C, 69.06; H, 11.65; N, 10.95. Found: C, 68.54; H, 11.92; N, 9.96. MS (FAB) m/z 696.4 [M+H]+; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 20 °C, TMS) δ 6.86-6.83 (t, 2H, HNCO), 4.72-4.70 (m, 1H, CH), 3.45-3.30 (m, 8H, (CH2)2NC(O)O, CH2NHC(O)), 2.41-2.35 (m, 4H, (CH2)2N), 2.21-2.20 (d, coherent peak, 12H, N(CH3)2), 2.19-2.11 (t, 4H, CH2CO), 1.58-1.53 (m, 4H, CH2CH2CO), 1.23-1.20 (coherent peak, 40H, 10(CH2)2), 0.84-0.81 (t, 6H, CH3); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3, 20 °C, TMS) δ 174.82 (NHCO), 156.37 (NC(O)O), 73.47 (CH), 59.28, 58.43, 46.98, 46.79, 40.66, 37.92, 33.10, 30.87, 30.84, 30.72, 30.59, 30.57, 30.55, 27.02, 23.89, 15.36.

In Vitro Transfection Studies

Aliquots of cationic lipids dissolved in chloroform were placed in 12 × 75 mm borosilicate glass disposable culture tubes using microliter syringes. Evaporation of chloroform under a stream of nitrogen gas was followed by high vacuum desiccation ensuring complete removal of residual solvent. The dry lipid films were then hydrated with buffer (40 mM Tris, pH 7.2) and subjected to several heat-vortex cycles. Lipoplexes were prepared with +/- charge ratios of 1:1, 2:1, and 4:1 by combining pDNA (pUC19 CMV-β-gal) and liposomes in serum free medium. To ensure reproducibility, plasmid solution was pipetted into the aqueous lipid dispersion and not the reverse [15].

Adherent B16-F0 murine melanoma skin cells were grown in DMEM Medium (supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 50 units/mL penicillin and 50 μg/mL streptomycin) and maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 in air atmosphere. Approximately 50,000 cells in 0.5 mL complete growth medium were added to each well of a 48 well tissue culture plate and incubated for 12 h prior to transfection. The medium was then removed and 250 μL lipoplex preparation containing 1 μg pUC19 were added per well. The cells were incubated for 4 h before the lipoplexes were removed and replaced with 0.5 ml of fresh serum medium. After an additional incubation period of 44 h, cell lysates were collected for analysis of reporter gene activity by employing the ONPG assay. Cytotoxicity and β-gal histochemistry were also performed, as described elsewhere [14].

A fluorescein label was covalently attached to the pUC19 plasmid with a labeling efficiency of approximately one marker molecule every 20-60 nucleic acid base pairs (Mirus Label IT™). Fluorescence images of intact cells transfected with labeled pDNA were acquired 8 h after lipofection using a Zeiss Axiovert 200M inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss).

pKa Study

DOPC/cholesterol (1/1 mol ratio) vesicles containing 5 mol% cationic lipid were prepared in 40 mM Tris at pH 7.2 and diluted in standard 4.5 mL fluorescence cuvettes with buffered solutions (40 mM Tris, 40 mM MES) of varying pH. TNS in deionized water was added to give a final lipid-probe mol ratio of 100:1. Samples were stirred for 0.5 h after which TNS fluorescence intensity was measured with a Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer (Varian Inc.) using excitation and emission wavelengths of 321 and 445 nm, respectively. The pH titration curves were fitted to

| (1) |

where A is the minimum fluorescence, B represents the difference between the maximum and minimum emission intensities, C is a parameter that adjusts the slope of the curve, and D is equal to the acid dissociation constant (pKa) of the cationic lipid. Nonlinear fitting was performed with Prostat (Poly Software International, version 3, New York).

Monolayer Studies at the Air-Water Interface

Cationic lipid monolayers were studied using a computer controlled KSV Minitrough (KSV Instruments Ltd.) equipped with a Wilhelmy plate electrobalance for measuring surface pressure and a barrier system for reducing the available surface area of the monolayer. With the aid of a microliter syringe (Hamilton Company), 10-25 μL lipid solution (<0.5 mg/mL cationic amphiphile in chloroform) were applied to the surface of 140-150 mL Tris buffer contained within a thermostated trough (242.25 cm2). After a time lag of 20 min to ensure complete evaporation of organic solvent, the monolayer was compressed at a constant rate of 10 mm/min. Plots were generated of surface pressure π versus mean molecular area A. Molecular compressibility was assessed from first derivative analysis of the π-A isotherm using the equation

| (2) |

where k is the compressibility modulus at a particular temperature T.

Phase Transition Temperature Studies

Studies were performed using a temperature-controlled cuvette in a Cary Eclipse spectrofluorometer, equipped with motorized polarizers, at an excitation wavelength of 351 nm. Samples were prepared by hydrating dry cationic lipid films together with DPH (100:1 mol ratio) in appropriate buffer to give a final lipid concentration of 0.5 mM. Fluorescence intensities of emitted light at 430 nm polarized parallel (Iv) and perpendicular (Ih) to the illuminating beam were recorded at different temperatures. Anisotropy (r) values at each temperature were calculated by the Cary Eclipse software (version 1.1) using the equation where G is a factor accounting for the polarization bias of the instrument. Nonlinear fitting of the experimental data was performed as described elsewhere [13].

Cationic Lipid-DNA Binding Studies

A. Agarose Gel Electrophoresis

pDNA (0.2 μg) and cationic lipid dispersions were combined in microfuge tubes to give +/- charge ratios ranging from 0.5:1 to 8:1 and diluted to 8 μl with buffer. Centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 15 s ensured proper mixing and the lipoplexes were stored at room temperature for 30 min before loading into the wells of a 0.8% agarose gel containing 0.5 μg/ml EtBr. Naked plasmid loaded into the outermost lanes served as a control. An electrophoretic field (5 V/cm) was applied for 0.5 h in 16 mM TAE pH 7.2, after which migration patterns were visualized with a Gel Logic 200 imaging system (Eastman Kodak Co.).

B. Ethidium Bromide Displacement Assay

In a quartz cuvette, ethidium bromide (0.8 μg) was combined with pDNA at a nucleotide-to-dye mol ratio of 34:1 and diluted to 3 ml with Tris buffer. Aliquots of aqueous liposomal dispersions were added under continuous stirring at +/- 0.2 charge ratio intervals. The reduction of EtBr fluorescence intensity was monitored at room temperature at an excitation wavelength of 515 nm. Emission readings (Fcomplex) at 595-605 nm were subtracted by the fluorescence signal of an ethidium bromide “blank” solution and normalized according to the equation

| (3) |

where F0 is fluorescence intensity of the sample prior to titration with lipid. The data was not corrected for light scattering effects which caused less than a 2% change in the fluorescence signal.

Particle Size and Electrophoretic Mobility Studies

Particle size and zeta potential measurements of cationic lipid dispersions and lipoplexes were performed at room temperature with a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS particle sizer (Malvern Instruments Inc., MA). Samples were prepared as in the biological studies under dust-free conditions. Mean diameters reported were obtained from Gaussian analysis of the intensity-weighted particle size distributions. Electrophoretic mobility was measured by the Laser Doppler Velicometry technique and converted by the instrument software (Dispersion Technology Software 3.00, Macromedia, Inc.) to zeta potential.

Computational Studies

The geometry optimization on the isolated polar headgroup, bis-(2-dimethylamino-ethyl)-aminocarboxylate, with three different protonation levels on the two terminal nitrogen atoms was performed using PM3 semi-empirical quantum chemical calculations [16] on over 200 conformations for each of the protonation levels. The lowest energy isomer found using the PM3 method was subsequently used as an initial geometry for ab initio calculations. The geometry optimization for ab initio calculation was carried out at the RHF/6-31G(d) level of theory by rotating two selected bonds; one rotation is around N6 and C7 and the other is around C7 and C8 (see Figure 2B for atom numbering). Each rotation was incremented 60° rotation angle from the PM3 global minima of the neutral headgroup molecule, totaling 12 rotations per molecule for each of the three different ionization levels. Each of the optimized structures was further characterized by Hessian, the second-derivatives of energy with respect to nuclear coordinates, to verify whether the optimized structure is a minimum, a transition state or a higher-order saddle point. In the present study, only the minima have been considered. In order to correlate the dimension of the headgroup with the experiments, the internuclear distance between two terminal nitrogens, denoted as DNN, was used as an indicator of the size of the headgroup. Each DNN was weighted by Boltzmann factor, and was summed as a contribution to the average internuclear distance between the two dimethylamine nitrogens, denoted as <DNN>. All calculations were performed by GAMESS quantum chemistry package [17].

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

This work was initiated based on the idea that increasing the distance between the saturated acyl chains of a double-chained cationic lipid (1,3-dialkyl analogs) would increase the conformational disorder of the lipid, resulting in a bilayer of increased fluidity. In order to compensate for the increased width of the hydrophobic moiety and retain cylindrical geometry (1,3lb2 versus 1,3lmt2 and 1,2lb2) which promotes assembly into lamellar structures, the ionizable cationic bis-(2-dimethylaminoethyl)amine group was used as the polar part. An additional advantage of the polar group is that, similar to the hydrophobic chains, it is symmetric. On the other hand, unlike the hydrophobic chains, it is pH-expandable, rendering the lipid molecule and the structure of the assembly pH-sensitive. It is emphasized that 1,3lb2 and 1,2lb2 are isomers; they have identical polar headgroup and hydrophobic parts, but with different spacer attachment sites of both parts. The synthesis of the isomers offers a great opportunity to delineate factors critical for transfection activity through systematic molecular changes.

Biological Analysis

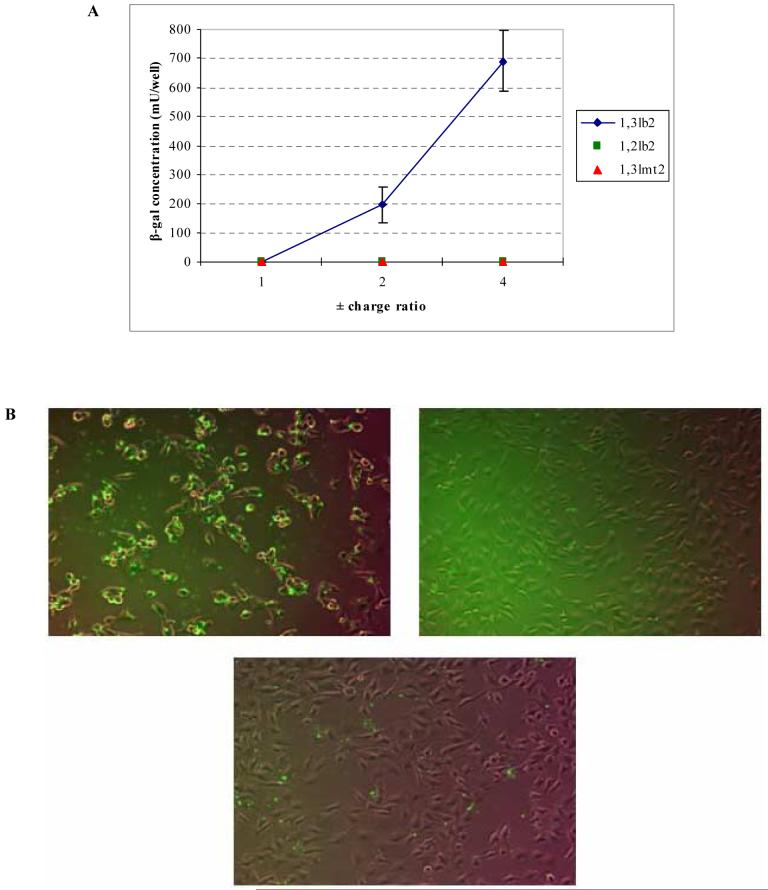

The ability of pDNA to transfect a B16-F0 melanoma cell line via cationic lipid-mediated delivery in the absence of helper lipids was assessed. Lipoplexes formulated with either the 1,2-dialkoylamidopropane-based amphiphile or the monovalent 1,3lmt2 lipid were found to be transfection inactive at all charge ratios tested (Figure 3A). Transfection mediated by the 1,3lb2 derivative resulted in significant levels of reporter gene expression at +/- 2:1 and 4:1. The β-galactosidase activity increased with the charge ratio, with a 3.5-fold rise from 2:1 to 4:1. Increasing this ratio beyond 4:1 resulted in decreased transfection activity (data not shown).

Figure 3.

(A) Levels of reporter enzyme produced within B16-F0 cells following cationic lipid-mediated transfection at +/- charge ratios of 1:1, 2:1 and 4:1, as determined by ONPG assay. The data presented are the average of three wells. Variations between experiments were found to be within 0.3-fold of the maximum activity presented. (B) Fluorescence of labeled pDNA in cells transfected with lipoplexes of 1,3lb2 (top left), 1,2lb2 (top right), and 1,3lmt2 (bottom center) at +/- 4:1. Images were acquired at 10× magnification 4 h after lipoplexes were removed from wells. (C) Representative X-gal staining of cells transfected with lipoplexes of 1,3lb2 (top), 1,2lb2 (center), and 1,3lmt2 (bottom) at +/- charge ratio equal to 2:1.

Detection of fluorescein covalently attached to the pDNA verified the superior gene delivery efficacy of 1,3lb2. Figure 3B shows overlayed brightfield and FITC images of cells following lipofection with labeled plasmid. pDNA transported with the aid of 1,3lb2 is present in a higher percentage of cells when compared to plasmid delivered by the other dimyristoyl derivatives. Cells that were exposed to lipoplexes containing 1,2lb2 exhibited the least uptake of exogenous nucleic acid, as indicated by the low level of green label.

Histochemical staining of cells as seen in Figure 3C clearly shows the differences in transfection activity of the cationic lipids quantitatively determined from the ONPG assay. MTT reduction analysis revealed low cytotoxicity at all charge ratios, with cationic lipid-induced cell death less than 30% (data not shown).

Physicochemical Characterization

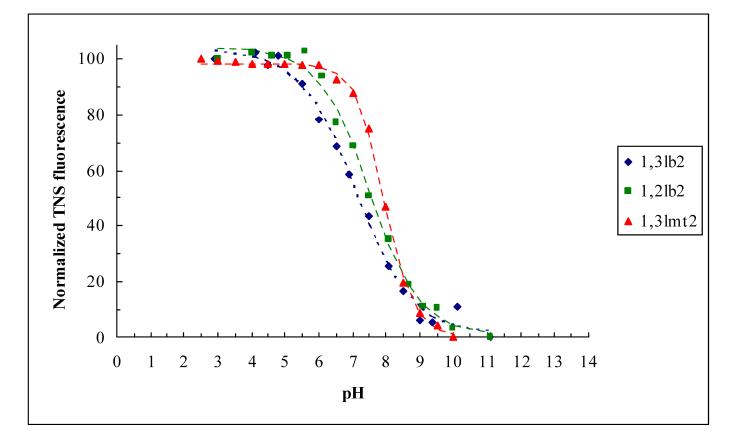

A. pKa Study

The surface potential probe TNS has been used for determination of acid dissociation constants of pH-sensitive amphiphiles [18,19]. Vesicles composed solely of cationic lipid undergo structural alterations across the pH range, therefore necessitating the formulation of pH stable cationic amphiphile/DOPC/cholesterol vesicles for the TNS assay. TNS is an anionic molecule whose fluorescence is undetected in water, and the probe will partition into the lipid bilayer membrane at low pH where it becomes fluorescent. As the pH shifts to the basic region, the deprotonation of the cationic lipid will expose TNS to a greater extent to the polar head of DOPC which, as in water, will result in quenching of TNS emission and decreased fluorescence intensity (Figure 4). Alternatively, at high pH the probe is expelled from the lipid vesicles into the aqueous surroundings where its fluorescence is quenched.

Figure 4.

Fluorescence intensity of TNS in DOPC/cholesterol/cationic lipid (0.95:0.95:0.1 mol ratio) vesicles as a function of pH. Best fits of the experimental data (solid points) are displayed with dashed lines.

The curve fits of the experimental data revealed pKa’s of 7.1, 7.5, and 7.9 for 1,3lb2, 1,2lb2 and 1,3lmt2, respectively (Table 1). Accordingly, the headgroup of the transfection active 1,3lb2 cationic lipid is only about 50% charged at pH 7.2, while only 16-37% of the inactive derivatives are in the neutral form. Given that the bivalent lipids possess the same polar head, the difference in their pKa’s is likely due to the influence of the intramolecular spatial arrangement of the hydrocarbon chains on the bilayer penetration depth of the diamine group. In addition, since electrostatics dominate cationic lipid-DNA interactions and govern cell internalization, it is logical to assume from the binding studies and zeta potential data that for liposomes composed of cationic lipid alone the active derivative 1,3lb2 is protonated to a greater degree at physiological pH than its transfection inefficient counterparts, despite having a lower intrinsic pKa. This contradiction between transfection activity and percentage of polar headgroup ionization is attributable to differences in hydration and packing of the derivatives in vesicles where they are well separated from one another and in purely cationic lipid assemblies where they are directly adjacent to each other.

Table 1.

Acid dissociation constants and other parameters of cationic lipids determined from nonlinear fitting of experimental data in Figure 4.

| Lipid | pKa | C* | Coefficient of determination† | % ionization at pH 7.2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,3lb2 | 7.09 | 0.52 | 0.994 | 49 |

| 1,2lb2 | 7.51 | 0.57 | 0.995 | 63 |

| 1,3lmt2 | 7.95 | 1.01 | 0.999 | 84 |

C is an adjustable parameter affecting the slope of the transition region of the fitted pH titration curves.

Goodness-of-fit statistics for pKa were assessed within a 95% confidence interval.

The pH titration curves were fitted to a modified version of the Henderson-Hasselbach equation that contains an adjustable parameter C which affects the slope of the transition region. With regards to the original equation, this parameter is equal to 1 for a univalent base (and -1 for a monoprotic acid) as is the case with the monovalent 1,3lmt2. The pKa’s listed in Table 1 for the bivalent lipids represent an average of two acid dissociation constants, one for each tertiary amine of the headgroup, resulting in pH titration curves with slopes of lower steepness (C less than unity) and in ionization percentages slightly deviating from Henderson-Hasselbach values.

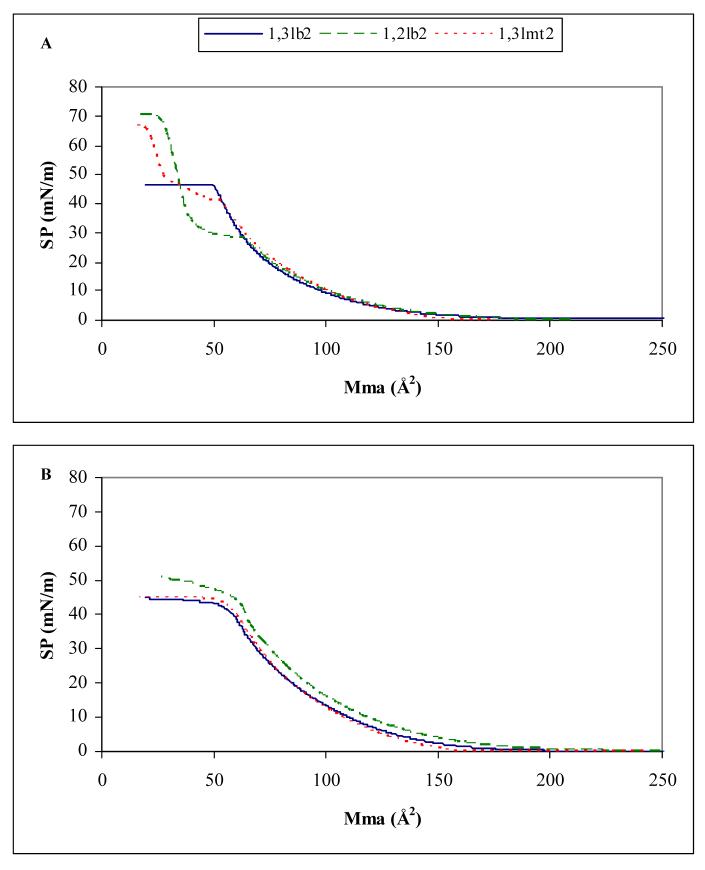

B. Langmuir Monolayer Studies

Investigating the interfacial properties of cationic lipids can provide in-depth knowledge into the interactions occurring between these lipids and those constituting cell and endosomal membranes. As previously mentioned, lipoplex binding to the cell surface and fusion with endosomal membranes are essential requirements for transfection. The surface properties, at the air-water interface, of cationic lipids in isolation were studied with the Langmuir film balance technique. Data is presented as a compression isotherm of surface pressure as a function of mean molecular area, and reveals information about lipid monolayers such as states of order, two-dimensional phase transitions, and collapse areas and pressures.

Monolayers of the transfection efficient 1,3lb2 cationic lipid exist in an all liquid-expanded state at 23 °C (Figure 5A). Collapse of the monolayer occurs at a surface pressure and mean molecular area of 42 mN/m and 56 Å2, respectively, after which the surface pressure plateaus nicely upon further compression. In contrast, monolayers of the 1,2 bivalent analog initially exhibit liquid-expanded behavior and the compressibility trace overlaps with the 1,3lb2 isotherm until a pressure and area of 28 mN/m and 69 Å2, respectively, at which point a transition from a fluid to highly compact, liquid-condensed phase occurs prior to monolayer collapse. Continued barrier closure causes a steep rise in surface pressure until the monolayer collapses at 59 mN/m and 40 Å2. Monolayers of 1,3lmt2 are also in a mixed phase state as evidenced by the L1-to-L2 transition in the compression isotherm. This two-dimensional phase transition, however, occurs at a much higher surface pressure consistent with a more pronounced fluid state associated with the greater spacing between the hydrophobic chains as opposed to 1,2lb2. Yet this increased interchain distance alone is inadequate in promoting significant reporter gene expression levels, as seen by the lack of activity of the monovalent species. The addition of a second tertiary amine group to the polar head leads to loosely packed lipids of increased hydration and fluidity, as indicated by the expanded mean molecular area of 1,3lb2 at monolayer collapse (Table 2), and is required for high transfection activity (Figure 3). At 37 °C the transitions vanish and monolayers of each derivative exist only in a liquid-expanded state with nearly identical collapse parameters (Figure 5B and Table 2).

Figure 5.

Surface pressure-mean molecular area isotherms of cationic lipids at (A) 23 and (B) 37 °C spread on Tris buffer (40 mM, pH 7.2). Monolayers at the air-water interface were compressed at a constant rate of 10 mm/minute.

Table 2.

Monolayer transition* and collapse parameters.

| Mean molecular area (Å2) | π (mN/m) | k (mN/m) | phase state† | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23 °C | 37 °C | 23 °C | 37 °C | 23 °C | 37 °C | 23 °C | 37 °C | |

| 1,3lb2 (n=4,3) | 55.98 (2.55) | 60.61 (2.29) | 41.62 (0.94) | 36.31 (1.37) | 86.67 (2.14) | 63.23 (3.20) | L1 | L1 |

| 1,2lb2 (n=4,6) | 39.5 (1.64) 68.6 (4.08) |

63.59 (1.96) | 59.05 (2.7) 28.25 (0.37) |

40.64 (0.71) | 121.3 (36.9) | 141.8 (HV) | L2 L1 |

L1 |

| 1,3lmt2 (n=6,2) | 25.5 (2.0) 55.3 (2.3) |

63.63 | 57.4 (1.3) 38.9 (1.1) |

37.83 (1.40) | 69.5 (5.9) | 67.12 (3.37) | L2 L1 |

L1 |

Measurements were performed with Tris buffer (40 mM, pH 7.2) as subphase. Values reported are the average of n number of experiments with standard deviations in parentheses.

Phase transition determined by a maximum in the plot of versus mean molecular area (not shown).

L1 and L2 symbolize liquid-expanded and liquid-condensed state, respectively.

HV denotes high variability.

A correlation between high molecular elasticity of cationic lipids and improved transfection activity via the Langmuir film balance technique has been previously shown [13,20,21]. The elasticity of the lipid monolayer is the inverse of the isothermal compressibility modulus; a low compressibility modulus signifies high interfacial elasticity. Compressibility moduli for 1,3lb2, 1,2lb2, and 1,3lmt2 at monolayer collapse and physiological temperature are 63, 142, and 67 mN/m, respectively, indicating a high two-dimensional elasticity for the transfection potent analog (Table 2).

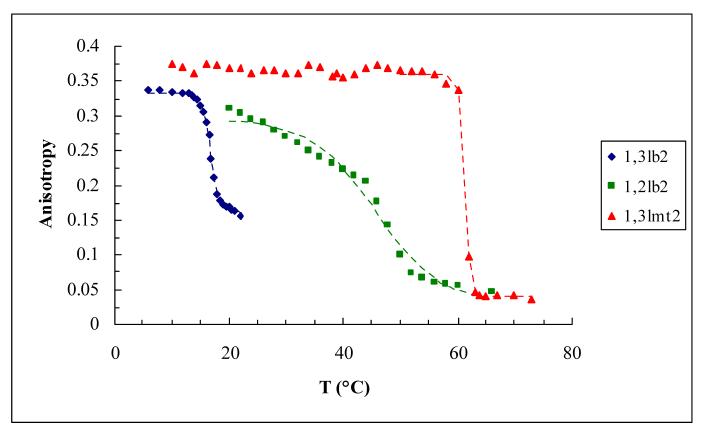

C. Phase Transition Temperature Studies

Fluorescence anisotropy is a means of characterizing the fluidity of lipid membranes [22] and has been linked to transfection activity [13]. The extrinsic fluorescent probe DPH is introduced to a liposome preparation, spontaneously incorporating within the hydrophobic interior of the lipid bilayer. At various temperatures the sample is exposed to polarized exciting light, and the depolarization of fluorescence, the extent of which depends on the degree of rotational freedom of the fluorophore as dictated by acyl chain state of order, is measured in terms of the steady-state fluorescence anisotropy. Phase diagrams of anisotropy as a function of temperature are sigmoidal plots from which gel-to-liquid crystalline transition temperatures are obtained (Figure 6A and Table 3). Only the transfection efficient derivative has a phase transition below physiological temperature. The sharp phase transition and smaller temperature range of transition of 1,3lb2 and its monovalent analog denote the highly cooperative nature of the phase transition of lipids with greater interchain spacing as compared to 1,2lb2.

Figure 6.

Nonlinear fitting of the anisotropy-temperature data used to determine the midpoint transition temperatures listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Phase transition parameters of cationic derivatives.

| Lipid | Tm(°C) | Coefficient of determination* |

|---|---|---|

| 1,3lb2 | 16.8 | 0.998 |

| 1,2lb2 | 45.7 | 0.983 |

| 1,3lmt2 | 61.3 | 0.999 |

Goodness-of-fit statistics for Tm were assessed within a 95% confidence interval.

The behavior of the cationic lipids in two-dimensional monolayers and three-dimensional bilayers was compared. For 1,3lb2 a gel-to-liquid crystalline transition temperature of 17 °C was found, and coincides with the fluid state of this lipid as indicated by the surface pressure-mean molecular area isotherm at 23 °C. All other derivatives displayed three-dimensional phase transitions well above 23 °C, exhibiting a more ordered nature in compliance with monolayer compression data confirming the existence of liquid-condensed phases at room temperature. However, the liquid-expanded state of 1,2lb2 and 1,3lmt2 in monolayers at 37 °C and anisotropy findings indicating a fluid phase of these lipids in bilayer assemblies above 46 and 61 °C, respectively, do not match. It should be noted that successive DSC scans of 1,3lmt2 revealed another transition at ∼40 °C (21), although this is not detected by fluorescence anisotropy due to sample turbidity (concentration independent).

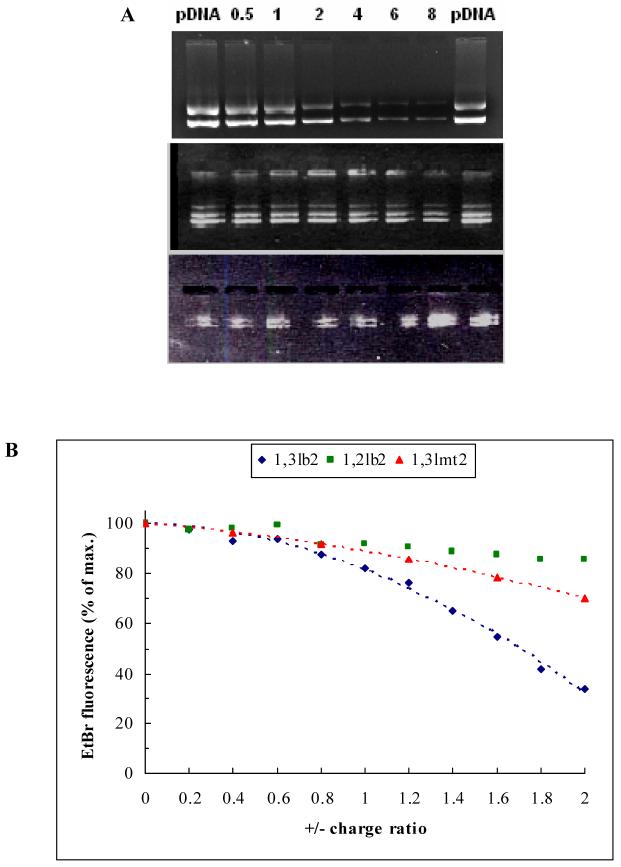

D. Cationic Lipid-DNA Binding Studies

Effective transfection is promoted, among other things, by efficient binding and compaction of pDNA by cationic liposomes in order to prevent plasmid degradation by enzymatic activity. The gel electrophoresis mobility shift assay was used to examine the plasmid complexation ability of the cationic derivatives. The ethidium bromide incorporated into the agarose gel intercalates between the base pairs of double-stranded DNA and its fluorescent properties are utilized to track plasmid migration in the presence of an electric field. Only naked plasmid can migrate through the gel, while pDNA-cationic liposome complexes will deposit on the bottom of the wells. Efficient complexation will result in retardation of pDNA migration and is visualized by either decreased or absent fluorescence in the gel. As Figure 7A shows, cationic lipids that did not elicit transfection activity failed to associate with plasmid. Only the 1,3lb2 derivative exhibited effective association with pDNA beginning at +/- 2:1 and increased with charge ratio, coinciding with the lipid’s transfection activity.

Figure 7.

(A) Agarose gel electrophoresis of lipoplexes containing either 1,3lb2 (top), 1,2lb2 (center), or 1,3lmt2 (bottom) prepared at various +/- charge ratios. Plasmid DNA alone loaded on the outermost lanes served as a negative control. (B) Binding curves of EtBr-intercalated pDNA titrated with aliquots of cationic lipid dispersions in 40 mM Tris at pH 7.2. The profiles were modeled as parabolas of the form y = -ax2 ± bx.

While the gel electrophoresis mobility shift assay describes the effectiveness with which cationic lipids complex pDNA, it does not reveal any information about plasmid compaction efficiency. For this purpose the ethidium bromide displacement assay was employed, which monitors the fluorescence signal reduction of intercalated probe upon titration of pDNA with aliquots of lipid. As pDNA is condensed by cationic liposomes, the EtBr intercalated between the plasmid base pairs is dislodged, and the intensity of the fluorescence signal decreases. Data plotted as % ethidium bromide displacement versus the +/- charge ratios of the lipoplexes is shown in Figure 7B. The 1,3lb2 lipid clearly displayed the greatest plasmid compaction efficacy, with 66% of the negative charges of the pDNA neutralized at +/- 2:1, providing the desired condensation and dehydration of the nucleic acid required for efficient in vitro transfection. Light scattering caused by aggregation precluded further data collection beyond this charge ratio for all derivatives. Parabolic fitting revealed complete EtBr displacement at +/- 2.4, an approximately two-fold decrease in the charge ratio at which the monovalent derivative produced full probe exclusion. 1,2lb2 was the least efficient in condensing pDNA, and concomitantly failed to induce reporter gene expression.

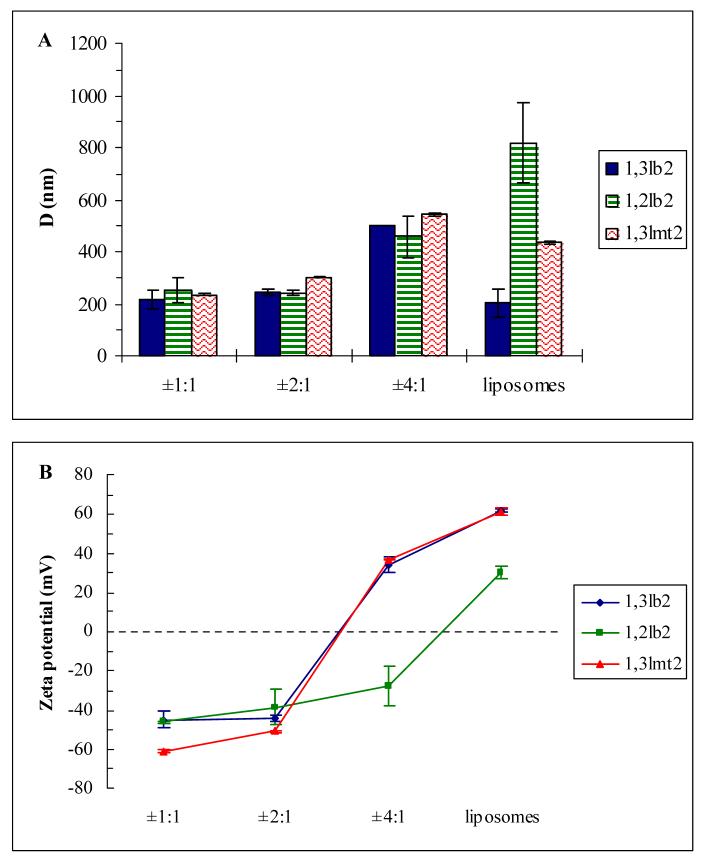

E. Particle Size and Electrophoretic Mobility Studies

Differences in the electrostatic interactions of these cationic lipid derivatives with pDNA were further analyzed via dynamic light scattering and electrophoretic mobility techniques. The initial lipid vesicle size was found to affect cationic lipid-mediated transfection competence, as previously shown [23]. Liposomal dispersions of the transfection efficient 1,3lb2 had the smallest particle size with a mean diameter of ∼200 nm (Figure 8A). When complexed to pDNA at the lowest +/- charge ratio tested, the size did not vary. This, as well as the approximate two-to three-fold reduction in mean diameter when vesicles of 1,3lmt2 and 1,2lb2, respectively, were combined with plasmid, indicate that lipoplexes of the dimyristoyl derivatives under investigation are not intact liposomes wrapped by adsorbed nucleic acids, as first suggested by Felgner and Ringold [24] and found by others [25]. Rather, the mechanism by which these self-assembled nanosystems are formed appears to involve in this case the destabilization of the bilayer structure causing extensive interactions between adjacent complexes such as membrane fusion and lipid mixing [26-28]. Plasmids are eventually wrapped by the cationic lipids into compact structures, and effective packaging will be affected by the elasticity of the lipid [29]. Fluid assemblies formed with amphiphiles of increased hydration commonly induce high transfection efficiency [13,20,30] which is corroborated by the monolayer studies.

Figure 8.

(A) Mean particle diameter and (B) zeta potential of cationic lipid dispersions and lipoplexes in Tris buffer (40 mM, pH 7.2).

Lipoplex size remained constant from +/- 1:1 to 2:1, and approximately doubled when the charge ratio was increased to 4:1. Interestingly, at each charge ratio the complex size was strikingly similar for all derivatives, ruling out factors like enhanced sedimentation of larger particles onto cells resulting in increased cellular association and uptake [31] or the size dependent nature of the various pinocytic internalization pathways, i.e. clathrin-mediated vs caveolae-mediated endocytosis [32,33], as major contributions to productive lipofection in vitro involving these derivatives.

Zeta potential was measured alongside particle size distribution and the results are shown in Figure 8B. Samples containing lipoplexes of 1,2lb2 displayed negative zeta potentials throughout the examined range of +/- charge ratios indicating that cationic lipid did not efficiently complex with and condense pDNA, as verified by agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide displacement. Interestingly, the zeta potential profile of the other transfection incompetent amphiphile mimicked that of the active 1,3lb2 lipid. This may be explained by the better hydration of 1,3lmt2. Another interesting find was the similarly low zeta potential values (from -39 to -51 mV) shared by all three analogs at +/- 2:1 which does not coincide with the tremendous disparity in transfection activity between the active lipid and inactive derivatives at this charge ratio.

Computational Analysis

The ab initio quantum chemical calculations were carried out to elucidate the dimensions of the polar headgroup under different ionic conditions and to correlate changes in molecular shapes with aggregate structure. At the RHF/6-31G(d) level of theory, there should be more than one conformer that have the similar low energy, but have quite different geometries, due to relatively flat nature of the potential energy surface. In order to correlate the experimental aggregate structure, the internuclear distance between the two terminal nitrogens, DNN, has been chosen as an indicator for the size of the headgroup.

The minima obtained for the neutral molecules resulted in 10 conformers by rotating the N6-C7 and C7-C8 bonds, with DNN ranging from 5.52 Å to 6.73 Å and energies ranging 1.7 kcal/mol from the lowest energy conformer. The energy-weighted <DNN> gave 6.57 Å. The singly-protonated molecules also resulted in 10 conformers by the similar bond rotations. The values of DNN ranged from 2.99 Å to 7.04 Å, and the energy range was 3.15 kcal/mol. Some conformers found for this species exhibit hydrogen bonding to the carbamide oxygen and one to the other terminal nitrogen, giving smaller dimensions. These results led to the average distance <DNN> to be 5.32 Å, giving the smallest average headgroup dimension in comparison with the neutral and doubly-protonated species. For the latter, the values of DNN ranged from 6.66 Å to 7.42 Å, and the energy range was 5.95 kcal/mol. The average distance <DNN> was calculated to be 7.06 Å and this is the largest among the different protonation levels, reflecting the electrostatic repulsion between the two positive charges on the terminal nitrogens. Collectively, the results clearly demonstrate that protonation changes the overall size of the headgroup. Furthermore, the surface area measurement of 1,31b2 at physiological pH (assuming a spherical polar headgroup and at monolayer collapse the mean molecular area is that of a single lipid molecule, r = 4.22 Å) correlates well with the end-to-end distance, the largest distance between H on the terminal methyl groups, calculated from the <DNN> value of the singly-protonated species (pKa = 7.1, Table 1).

CONCLUSION

The current investigation was put forth in an effort to shed light on the influence of systematic molecular conformational changes on cationic lipid assemblies and their gene delivery capabilities. Three myristoyl derivatives were examined, differing in the number of polar headgroup tertiary amines and interchain distance between the hydrophobic chains. Langmuir monolayer studies and fluorescence anisotropy revealed high molecular elasticity and increased acyl chain fluidity, respectively, of the transfection active 1,3lb2 lipid. Efficient binding and moderate compaction of pDNA were correlated with high transfection activity, as determined by agarose gel electrophoresis and EtBr exclusion assay, respectively. Dynamic light scattering showed that the size of liposomes, not lipoplexes, had an effect on transgene expression. The zeta potential and pKa studies were very useful as indicative measures of lipofection efficiency but should be analyzed always in combination with other analytical techniques.

The geometry of these surfactants, as defined by their packing parameter [34], has an effect on cationic lipid phase structure (i.e. micellar vs lamellar phase) and thus controls other relevant properties such as me mbrane fusion and nucleic acid complexation. According to the theory developed by Israelachvili and coworkers [35], double-chained lipids having a cylindrical molecular geometry should organize into lamellar structures. 1,3lb2 was designed to display this geometry at physiological pH for assembly of stable lipid bilayers. The increased fluidity imparted by the greater intramolecular spacing of the acyl chains, relative to the corresponding 1,2-dimyristoyl derivative, allows for extensive lipid mixing during lipoplex formation and efficient wrapping of pDNA into a compact, well protected structure for cell internalization. As predicted by the computational studies, the protonation of both terminal nitrogens at acidic pH and expansion of the polar headgroup due to repulsive forces modify the molecular geometry of 1,3lb2 to resemble a cone shape (the presence of only a single ionizable group in the hydrophilic region of 1,3lmt2 precludes such a conformational change). This in turn favors formation of nonbilayer phases that facilitate fusion with the endosomal membrane.

In summary, physicochemical characterization revealed that the dimyristoyl cationic lipid with a symmetric bivalent polar headgroup and greater intramolecular distance between the hydrophobic chains forms assemblies that induce high transfection activity through efficient binding and compaction of pDNA, increased acyl chain fluidity, and high molecular elasticity. The structure-activity relationships presented here offer insightful contributions to the rational design and synthesis of superior cationic lipid vectors for gene therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by a Pre Doctoral Fellowship in Pharmaceutics from the PhRMA Foundation (Washington, DC) and National Institutes of Health Grant EB004863.

ABBREVIATIONS

- EtBr

ethidium bromide

- lb

lipid bivalent

- lmt

lipid monovalent tertiary

- MLV

multilamellar vesicle

- pDNA

plasmid DNA

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Felgner PL, Gadek TR, Holm M, Roman R, Chan HW, Wenz M, Northrop JP, Ringold GM, Danielsen M. Lipofection: a highly efficient, lipid-mediated DNA-transfection procedure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1987;84:7413–7417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu D, Qiao W, Li Z, Zhang S, Cheng L, Jin K. Synthetic diether-linked cationic lipids for gene delivery. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2006;67:248–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2006.00366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Decastro M, Saijoh Y, Schoenwolf GC. Optimized cationic lipid-based gene delivery reagents for use in developing vertebrate embryos. Dev. Dyn. 2006;235:2210–2219. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ewert KK, Evans HM, Bouxsein NF, Safinya CR. Dendritic cationic lipids with highly charged headgroups for efficient gene delivery. Bioconjug. Chem. 2006;17:877–888. doi: 10.1021/bc050310c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guissouma H, Froidevaux MSC, Hassani Z, Demeneix BA. In vivo siRNA delivery to the mouse hypothalamus confirms distinct roles of TR beta isoforms in regulating TRH transcription. Neurosci. Lett. 2006;406:240–243. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li SD, Huang L. Targeted delivery of antisense oligodeoxynucleotide and small interference RNA into lung cancer cells. Mol. Pharm. 2006;3:579–588. doi: 10.1021/mp060039w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wasungu L, Stuart MCA, Scarzello M, Engberts JBFN, Hoekstra D. Lipoplexes formed from sugar-based gemini surfactants undergo a lamellar-to-micellar phase transition at acidic pH. Evidence for a non-inverted membrane-destabilizing hexagonal phase of lipoplexes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1758:1677–1684. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bally MB, Harvie P, Wong FMP, Kong S, Wasan EK, Reimer DL. Biological barriers to cellular delivery of lipid-based DNA carriers. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1999;38:291–315. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(99)00034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu Y, Szoka FC., Jr. Mechanism of DNA release from cationic liposome/DNA complexes used in cell transfection. Biochemistry. 1996;35:5616–5623. doi: 10.1021/bi9602019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koynova R, MacDonald RC. Lipid transfer between cationic vesicles and lipid-DNA lipoplexes: Effect of serum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1714:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koynova R, Wang L, MacDonald RC. An intracellular lamellar-nonlamellar phase transition rationalizes the superior performance of some cationic lipid transfection agents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:14373–14378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603085103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ewert K, Slack NL, Ahmad A, Evans HM, Lin AJ, Samuel CE, Safinya CR. Cationic lipid-DNA complexes for gene therapy: Understanding the relationship between complex structure and gene delivery pathways at the molecular level. Curr. Med. Chem. 2004;11:133–149. doi: 10.2174/0929867043456160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Savva M, Chen P, Aljaberi A, Selvi B, Spelios M. In vitro lipofection with novel asymmetric series of 1,2-dialkoylamidopropane-based cytofectins containing single symmetric bis-(2-dimethylaminoethane) polar headgroups. Bioconjug. Chem. 2005;16:1411–1422. doi: 10.1021/bc050138c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheikh M, Feig J, Savva M. In vitro lipofection with novel series of symmetric 1,3-dialkoylamidopropane-based cationic surfactants containing single primary and tertiary amine polar head groups. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2003;124:49–61. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(03)00033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu Y, Hui SW, Frederik P, Szoka FC., Jr. Physicochemical characterization and purification of cationic liposomes. Biophys. J. 1999;77:341–353. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)76894-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stewart JJP. Optimization of parameters for semi-empirical methods. I. Method. J. Comput. Chem. 1989;10:209–220. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmidt MW, Baldridge KK, Boatz JA, Elbert ST, Gordon MS, Jensen JH, Koseki S, Matsunaga N, Nugyen KA, Su S, Windus TL, Dupuis M, Montgomery JA. General atomic and molecular electronic structure system. J. Comput. Chem. 1993;14:1347–1363. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bailey AL, Cullis PR. Modulation of membrane fusion by asymmetric transbilayer distributions of amino lipids. Biochemistry. 1994;33:12573–12580. doi: 10.1021/bi00208a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hafez IM, Cullis PR. Cholesteryl hemisuccinate exhibits pH sensitive polymorphic phase behavior. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2000;1463:107–114. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00186-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aljaberi A, Chen P, Savva M. Synthesis, in vitro transfection activity and physicochemical characterization of novel N,N’-diacyl-1,2-diaminopropyl-3-carbamoyl-(dimethylaminoethane) amphiphilic derivatives. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2005;133:135–149. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Savva M, Aljaberi A, Feig J, Stolz DB. Correlation of the physicochemical properties of symmetric 1,3-dialkoylamidopropane-based cationic lipids containing single primary and tertiary amine polar headgroups with in vitro transfection activity. Colloids Surf. B. 2005;43:43–56. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lentz BR. Membrane “fluidity” as detected by diphenylhexatriene probes. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 1989;50:171–190. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koumbi D, Clement JC, Sideratou Z, Yaouanc JJ, Loukopoulos D, Kollia P. Factors mediating lipofection potency of a series of cationic phosphonolipids in human cell lines. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1760:1151–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Felgner PL, Ringold GM. Cationic liposome-mediated transfection. Nature. 1989;337:387–388. doi: 10.1038/337387a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salvati A, Ciani L, Ristori S, Martini G, Masi A, Arcangeli A. Physicochemical characterization and transfection efficacy of cationic liposomes containing the pEGFP plasmid. Biophys. Chem. 2006;121:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caracciolo G, Pozzi D, Amenitsch H, Caminiti R. Multicomponent cationic lipid-DNA complex formation: role of lipid mixing. Langmuir. 2005;21:11582–11587. doi: 10.1021/la052077c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kennedy MT, Pozharski EV, Rakhmanova VA, MacDonald RC. Factors governing the assembly of cationic phospholipid-DNA complexes. Biophys. J. 2000;78:1620–1633. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76714-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oberle V, Bakowsky U, Zuhorn IS, Hoekstra D. Lipoplex formation under equilibrium conditions reveals a three-step mechanism. Biophys. J. 2000;79:1447–1454. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76396-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wasungu L, Hoekstra D. Cationic lipids, lipoplexes and intracellular delivery of genes. J. Control. Release. 2006;116:255–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scarzello M, Chupin V, Wagenaar A, Stuart MCA, Engberts JBFN, Hulst R. Polymorphism of pyridinium amphiphiles for gene delivery: influence of ionic strength, helper lipid content, and plasmid DNA complexation. Biophys. J. 2005;88:2104–2113. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.053983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ross PC, Hui SW. Lipoplex size is a major determinant of in vitro lipofection efficiency. Gene Ther. 1999;6:651–659. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rejman J, Oberle V, Zuhorn IS, Hoekstra D. Size-dependent internalization of particles via the pathways of clathrin- and caveolae-mediated endocytosis. Biochem. J. 2004;377:159–169. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rejman J, Bragonzi A, Conese M. Role of clathrin- and caveolae-mediated endocytosis in gene transfer mediated by lipo- and polyplexes. Molec. Ther. 2005;12:468–474. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsu WL, Chen HL, Liou W, Lin HK, Liu WL. Mesomorphic complexes of DNA with the mixtures of a cationic surfactant and a neutral lipid. Langmuir. 2005;21:9426–9431. doi: 10.1021/la051863e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Israelachvili JN, Marcelja S, Horn RG. Physical principles of membrane organization. Q. Rev. Biophys. 1980;13:121–200. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500001645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]