Abstract

Processing of most PC zymogens is required for successful folding and/or passage through the secretory pathway; active site mutants are retained in the ER and degraded. We here report that the active site serine mutant of PC2 (PC2-S383A) was efficiently secreted as the intact zymogen in CHO-K1 cells, suggesting that its propeptide can productively insert into the mutated binding pocket without causing misfolding. In AtT-20 cells, PC2-S383A was cleaved at the secondary cleavage site within the propeptide; this cleavage event was pH-dependent and was inhibited by a proprotein convertase inhibitor. In vitro digestion of PC2-S383A with various convertases indicates that this site is accessible to in trans cleavage. Abundant immunoreactive S383A PC2 was found in secretory granules, supporting the idea that this protein is efficiently trafficked through the secretory pathway.

Keywords: active site mutant, processing, prohormone convertase, sorting, zymogen

Introduction

Proprotein convertases (PCs) are proteases belonging to the subtilisin family which are responsible for maturation of a variety of enzymes, prohormones and neuropeptide neurotransmitters [1]; the cleavage of these precursors occurs at either single or paired basic residues. All convertases share certain structural features: a signal peptide, a propeptide, a catalytic domain, a P-domain, and a C-terminal domain [2]. The propeptides of mammalian PCs exhibit 30–67% sequence identity to each other [3]. These propeptide segments are required for the correct folding of their cognate catalytic domains, thus acting as intramolecular chaperones [4] and also function as potent autoinhibitors [5]. The catalytic domains contain the Ser-His-Asp catalytic triad, which effects substrate cleavage [6]. The propeptides of furin, PACE4, PC1, PC6, and PC7 are cleaved from the remainder of the molecule early in biosynthesis, in the ER; this primary cleavage event occurs via autocatalytic processing [7]. However, the cleaved propeptide of furin still remains associated with the enzyme until it reaches the more acidic TGN/secretory granule compartment, which triggers a secondary cleavage, resulting in propeptide dissociation and release [7]. It is still unclear as to whether the secondary processing of propeptide is absolutely necessary for the activation of all convertases [3]. The cell biology of PC2 is somewhat different than that of furin or PC1. ProPC2 spends an unusually long time in the ER compared to other convertases, and then binds to a partner protein, 7B2, which escorts it to the TGN and renders the zymogen competent for autoactivation [8]; our working hypothesis is that 7B2 blocks the assumption of an inactivatable proPC2 conformer (SNL and IL, unpublished results).

Interestingly, catalytic triad mutants of human furin (furD46A, furH87A, and furS261A) do not undergo autocatalytic maturation, but instead accumulate in the ER [9,10]; similar results were found for a catalytic site mutant of PC1, PC1-S382A [11]. In this paper we have investigated the fate of a catalytic site mutant of proPC2 and show that in contrast to other convertases, this active site mutant is apparently folded correctly, as evidenced by its ability to efficiently traverse the secretory pathway.

Materials and methods

Construction of mutated PC2

A full-length mouse proPC2 cDNA [12] cloned into the pcDNA3 expression vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used as a plasmid DNA template. Mutations were introduced into proPC2 cDNA using the QuikChange® Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The mutagenesis primers used for the proPC2-S383A mutant were: 5’-CGGAGCAGCTGCAGCTGTCCCAGAATGTCT-3’ and 5’-AGACATTCTGGGACAG CTGCAGCTGCTCCG-3’.

Cell Culture, Transfection, and Selection

All cells were cultured at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. PC2 WT and PC2-S383A were expressed in CHO-K1 cells by transfection with FUGENE™6 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). CHO-K1 cells were cotransfected with a pEE14 plasmid (Lonza Biologics, Slough, UK) encoding 21 kDa 7B2 and a pcDNA3 plasmid encoding either PC2 WT or PC2-S383A. The expression of PC2-S383A was screened using Western blotting with a PC2 antiserum LS18 directed against the COOH-terminus of mature PC2 [12]. High-expressing stable clones were selected in MEM medium lacking glutamine and supplemented with non-essential amino acids + gentamycin + sodium pyruvate (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and the appropriate selection agent (800 μg/ml G418 for pcDNA3/PC2; 25 uM methionine sulfoximine for pEE14/7B2).

An AtT-20 cell line stably expressing 21 kDa 7B2 (AtT-20/7B2) [13] was used as the starting material for transfection with a pcDNA3 plasmid encoding either PC2 WT or PC2-S383A. Stable clones were selected with 500 μg/ml G418 (Invitrogen, Gaithersburg, MD) and 50 μg/ml hygromycin (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) in DMEM high glucose medium + 10% NuSerum + 2.5% FBS. Three independent high-expressing clones were used for subsequent experiments.

Metabolic labeling and immunoprecipitation

AtT-20 cells were labeled with 0.5 mCi/ml of [35S]-methionine and cysteine (Met/Cys) Promix (Amersham Corp., Arlington Heights, IL) for 20 min and chased for 90 min. Forskolin was used at concentrations of 10 μM as a secretagogue. In some experiments, cells were incubated with either 1 μM bafilomycin A1 (Kamiya Biomedical Co., Seattle, WA) or 100 μM CMK (Alexis USA, San Diego, CA). Immunoprecipitations were performed using PC2 antiserum, as described [13].

Enzyme purification

Recombinant PC2 WT and PC2-S383A were obtained from the conditioned medium via purification on a Mono Q anion-exchange column (Amersham Biosciences, Pittsburgh, PA) as described previously [14]. Positive fractions were fractionated on a Superdex 200 10/300 GL gel filtration column (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Endoproteolytic cleavage of proPC2

For spontaneous cleavage of proPC2, purified PC2 WT or PC2-S383A were incubated at 37°C in 100 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.0, containing 5 mM CaCl2, 0.1% Brij, and 0.5 mM DTT. For the examination of endoproteolytic processing with other PCs, 100 mM Bis-Tris/100 mM sodium acetate buffer at the desired pH (adjusted with either acetic acid or sodium hydroxide; for furin, PACE4, and PC6, pH 7.0; for PC1 and PC7, pH 5.5) was used. Human furin was expressed in CHO cells and purified as previously described [15], while PC6 and PC7 were expressed using the DES expression system [16].

Results

ProPC2 mutated at an active site residue is secreted as an intact zymogen in constitutively-secreting cells

After mutagenesis of the serine active site residue (PC2-S383A) and expression in CHO-K1/7B2 cells, PC2-S383A was secreted as the unprocessed zymogen (Fig. 1B). Additionally, as expected, purified PC2-S383A was present only as a zymogen form even at a pH low in vitro enough to autoactivate wild type PC2 (showing that it is enzymatically inert; Fig. 1B) [14]. PC2-S383A was not cleaved even after overnight incubation (data not shown).

Fig. 1. ProPC2-S383A is secreted as the zymogen in CHO-K1 cells; this proprotein does not undergo processing at low pH in vitro.

A. Sequence of the PC2 propeptide; Three potential cleavage sites within the proPC2 propeptide are shown in bold; the primary and secondary sites known to be cleaved [21] are indicated. B. Purified PC2 and PC2-S383A were incubated at pH 5.0 for the indicated times and were immunoblotted with PC2 antiserum.

ProPC2-S383A is cleaved at the secondary cleavage site and can be targeted to secretory granules in regulated cells

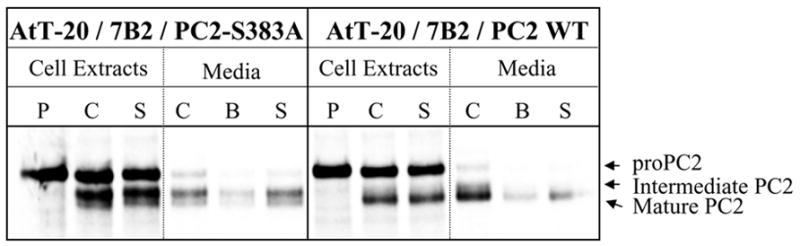

In order to determine whether proPC2-S383A is also secreted as a zymogen from an endocrine cell line, we labeled AtT-20/7B2/PC2 WT and AtT-20/7B2/PC2-S383A cells using 35S-Met/Cys and immunoprecipitated labeled cell extracts and chase media with antiserum against PC2. 35S-labeling of these cells showed that WT proPC2 was processed at the primary cleavage site to mature PC2, while proPC2-S383A was cleaved at a secondary cleavage site, producing a larger intermediate (Fig. 2). Since proPC2-S383A cannot be cleaved autocatalytically, this result indicates that other proteases must mediate internal processing of proPC2-S383A in AtT-20 cells. In addition, when radiolabeled extracts obtained from AtT-20/7B2/PC2-S383A cells were immunoprecipitated using PC2 antiserum, 7B2 was coimmunoprecipitated with PC2-S383A (data not shown). To investigate the sorting of PC2-S383A into the regulated secretory pathway, after the initial 90-min chase period, cells were incubated in fresh medium for 20 min (basal secretion) and subsequently chased for 20 min in the presence of secretagogue, 10 uM forskolin. We observed that a significant amount of the 35S-labeled PC2-S383A was secreted from the cells in the presence of forskolin (Fig. 2), suggesting that PC2-S383A is stored efficiently in the secretory pathway.

Fig. 2. ProPC2-S383A is cleaved at the secondary cleavage site and sorted into secretory granules in AtT-20 cells.

AtT-20/7B2/ PC2WT and AtT-20/7B2/ PC2-S383A cells were labeled with 35S-Met/Cys for 20 min, then chased for 90 min. Cells were sequentially incubated in the fresh medium for 20 min, then in medium containing 10 μM forskolin for 20 min. Cell extracts and the chase media were immunoprecipitated with PC2 antiserum. Abbreviations; P, pulse; C, chase; B, basal secretion; S, stimulated secretion.

In order to determine whether other proprotein convertases have a role in the proPC2-S383A processing, AtT-20 cells were treated with a synthetic specific inhibitor of proprotein convertases, CMK during the chase period (180 min). Since the propeptide of wild type PC2 occupies the catalytic pocket until arrival at the TGN, where propeptide processing occurs autocatalytically [8], CMK cannot enter the pocket until after the propeptide is removed. Therefore, we expected to find that CMK cannot inhibit PC2 propeptide processing at the primary site, and this was indeed observed (Fig. 3). However, we also observed that CMK treatment completely inhibited secondary cleavage of the PC2-S383A propeptide (Fig. 3), indicating that this PC2 S383A processing event is likely to be mediated by other convertases.

Fig. 3. ProPC2-S383A processing at the secondary cleavage site is partially pH-dependent and proprotein convertase-dependent.

AtT-20/7B2/ PC2WT and AtT-20/7B2/ PC2-S383A cells were labeled with 35S-Met/Cys for 20 min and chased for 180 min in the presence of either 1 μM bafilomycin A1 or 100 μM CMK followed by immunoprecipitation with PC2 antiserum. Abbreviations; S, signal peptide; P, propeptide; C, catalytic domain; PD, P domain; CT, C-terminal domain.

In order to distinguish between the potential contribution of neutral and acidic enzymes to secondary site processing in vivo, we tested whether secondary site propeptide processing of proPC2-S383A in AtT-20 cells is pH-dependent. Cells were labeled using 35S-Met/Cys and then incubated during a 180-min chase in the presence of bafilomycin A1, a specific inhibitor of the vacuolar H+-ATPase [17], which prevents the acidification of the pH in the TGN and the secretory granules. This treatment inhibited propeptide cleavage of proPC2-S383A as well as the maturation of WT proPC2 (Fig. 3), suggesting that these two proteolytic events are at least partially pH-dependent.

We next investigated which proprotein convertase could potentially mediate PC2 S383A processing at the secondary site. Purified proPC2-S383A was incubated in the presence of various purified convertases in vitro under the pH conditions appropriate for each convertase. Figure 4A shows that furin, PC1, and PC6 all generated PC2-S383A which was fully processed at the secondary site, while PACE4 and PC7 partially cleaved at this site. However when we incubated PC2-S383A with wild type PC2 in vitro, the PC2-S383A propeptide could not be cleaved by active PC2 (Fig. 4B). These data indicate that several different proprotein convertases, but not PC2, could potentially be responsible for secondary site processing of PC2-S383A in AtT-20 cells; however, the fact that low pH was required strongly hints at the physiological involvement of PC1.

Fig. 4. Proprotein convertases can cleave PC2 S383A at the secondary cleavage site in vitro.

A, Purified PC2 alone and PC2 S383 with several PCs (furin, PACE4, PC6, PC7 and PC1) were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. B, Purified PC2 (middle), PC2-S383A (left), or both (right) were incubated at pH 5.0 for the indicated times, respectively. Samples were immunoblotted with PC2 antiserum.

Discussion

The PC2 propeptide has three potential cleavage sites (Fig. 1A). We have previously investigated the processing and sorting of the PC2 propeptide and shown using mutagenesis that the primary cleavage site is involved in the folding of the binding pocket, while the secondary site processing is not [18]. Activation of proPC2 occurs autocatalytically once the pH is lowered [14]; since Ser383 provides the hydroxyl nucleophile for attack of the scissile peptide bond [6], we expected that proPC2 mutated at this catalytic residue would not undergo propeptide cleavage, and this was indeed found to be the case. Our data clearly show that PC2-S383A is secreted as the intact zymogen from CHO-K1/7B2 cells. This result stands in contrast to data obtained for other convertases, which indicate that catalytic triad mutants of human furin (furD46A, furH87A, and furS261A) expressed in transfected COS-1 cells are retained in the ER and are unable to undergo autocatalytic maturation [9,10]. Similarly, when PC1-S382A was expressed in HEK293 cells, no processed and secreted enzyme was detected, suggesting ER retention similar to furin [11]. Our observation that the PC2-S383A mutant was secreted as effectively as wild type enzyme from CHO-K1 cells suggests that for PC2, possibly alone among convertases, the serine to alanine active site mutation does not affect the ability of the zymogen to fold correctly. Interestingly, a different active site mutant of hPC2 (D142N-hPC2) expressed in COS-7 cells was found to accumulate in the ER/early Golgi as a zymogen; the authors stated this might be due to incorrect insertion of the propeptide into the active site [19]. It is possible that the D142N mutation disrupts the folding of the catalytic site in a manner in which our serine to alanine mutant does not.

Our previous study of wild-type PC2 biosynthesis has shown that the PC2 propeptide is internally processed within the secretory granules in AtT-20 cells co-expressing 7B2 with PC2; unlike other convertases, proPC2 mutated at the secondary processing site can still generate active enzyme [18], suggesting that cleavage at the secondary site is not required for propeptide dissociation from the enzyme, as it is for other convertases. Thus, we were curious to see if secondary site propeptide cleavage of PC2-S383A would occur within the regulated secretory pathway. Interestingly, we found that in AtT-20 cells the PC2-S383A mutant was cleaved intracellularly at this cleavage site, and that processing was completely inhibited by a proprotein convertase inhibitor, CMK. We note that in the presence of bafilomycin A1 the amount of the internally processed PC2-S383A was significantly reduced; we speculate that this reduction in acidification results in less than optimal conditions for the enzyme responsible for this processing event. With regard to the identification of this enzyme activity, furin is known to be quite active at neutral pH; it exhibits greater than 50% of maximal activity between pH 6.0 and 8.5 [20]. The convertases PC6 and PACE4 have a broad pH optimum with peak activity at neutral to weakly basic pHs (7.0-8.0 for PC6; 7.0–8.5 for PACE4) [21]. In contrast to these other convertases, PC1 active forms are active within a much narrower pH range; 87 kDa PC1 has an optimum pH between pH 5.5 and 6.5 [22] and 74/66 kDa PC1 displays an even narrower pH optimum (between 5.0 and 5.5) with significantly reduced activity at neutral pH [23]. Therefore, a promising candidate for at least a portion of the PC2-S383A secondary propeptide cleavage is the endogenous convertase PC1. We observed that various convertases including furin, PC1, PC6, PACE4, and PC7 could cleave proPC2-S383A at the secondary site in vitro. Wild type proPC2 was similarly cleaved by other convertases in vitro (data not shown), suggesting that the secondary cleavage site of both wild type proPC2 and proS383A propeptide is accessible to cleavage under both neutral and acidic pH conditions in vitro. However, in a neuroendocrine cell line, efficient secondary site cleavage of proPC2-S383A required acidic conditions, supporting the notion that this cleavage event occurs within the acidic milieu of secretory granules- possibly by PC1. The fact that PC2 itself could not accomplish this cleavage is consistent with our previous observation that secondary site cleavage of iodinated propeptide could not be accomplished by activated PC2 in vitro [18] and suggests that the secondary cleavage site sequence is a poor PC2 substrate.

Taken together, our results suggest that for proPC2, unlike other convertases, the substitution of serine by a small amino acid like alanine does not affect the local structure of the binding pocket. Thus, the PC2 propeptide can apparently correctly insert into the mutated pocket and the zymogen/7B2 complex can undergo appropriate sorting via either the regulated and constitutive secretory pathway, depending on the cell type. Why AtT-20 cells, but not CHO-K1 cells, are able to cleave at the secondary propeptide cleavage site remains unclear; potential reasons include one or more of the following i) relatively low levels of furin and/or lack of PC1 within the secretory pathway of CHO-K1 cells [24];and/or ii) the relatively short intracellular retention times of constitutively secreted proteins.

In summary, we have shown here that internal processing of the PC2 propeptide in an active site serine-to-alanine mutant occurs via an intermolecular pathway mediated by other convertases in neuroendocrine cells, but does not occur in constitutively-secreting cells, which efficiently secrete apparently well-folded mutant zymogen. Our ability to purify the intact zymogen from PC2-S383A-producing CHO-K1 cells co-expressing 21 kDa 7B2 should lead to a better understanding of its molecular structure including its interaction with 7B2, its complex activation mechanism, and the development of specific and potent PC2 inhibitors for therapeutic use.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Joelle Finley and Josephine Roussell for help in preparing tissue culture reagents. We thank Don Steiner for persuading us to create this active-site mutant. This work was supported by DA05084 from NIDA.

Abbreviation used

- CMK

decanoyl-Arg-Val-Lys-Arg-chloromethylketone

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- PCs

proprotein convertases

- TGN

trans-Golgi network

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Seidah NG, Chretien M. Eukaryotic protein processing: endoproteolysis of precursor proteins. Curr Opin Botechnol. 1997;8:602–607. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(97)80036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muller L, Lindberg I. The cell biology of the prohormone convertases PC1 and PC2. In: Moldave K, editor. Progress in Nucleic Acids Research. Academic Press; San Diego: 1999. pp. 69–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seidah NG, Day R, Marcinkiewicz M, Chretien M. Precursor convertases: an evolutionary ancient, cell-specific, combinatorial mechanism yielding diverse bioactive peptides and proteins. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1998;839:9–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson ED, Molloy SS, Jean F, Fei H, Shimamura S, Thomas G. The ordered and compartment-specific autoproteolytic removal of the furin intramolecular chaperone is required for enzyme activation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:12879–12890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108740200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Creemers JW, Jackson RS, Hutton JC. Molecular and cellular regulation of prohormone processing. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1998;9:3–10. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1997.0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rockwell NC, Thorner JW. The kindest cuts of all: crystal structures of Kex2 and furin reveal secrets of precursor processing. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henrich S, Lindberg I, Bode W, Than ME. Proprotein Convertase Models based on the Crystal Structures of Furin and Kexin: Explanation of their Specificity. J Mol Biol. 2005;345:211–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muller L, Zhu X, Lindberg I. Mechanism of the facilitation of PC2 maturation by 7B2: involvement in ProPC2 transport and activation but not folding. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:625–638. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.3.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Creemers JWM, Siezen RJ, Roebroek AJM, Ayoubi TAY, Huylebroek D, van de Ven WJM. Modulation of furin-mediated proprotein processing activity by site-directed mutagenesis. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:21826–21834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Creemers JW, Vey M, Schafer W, Ayoubi TA, Roebroek AJ, Klenk HD, Garten W, van de Ven WJ. Endoproteolytic cleavage of its propeptide is a prerequisite for efficient transport of furin out of the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol chem. 1995;270:2695–2702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.6.2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou A, Paquet L, Mains RE. Structural elements that direct specific processing of different mammalian subtilisin-like prohormone convertases. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:21509–21516. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.37.21509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen FS, Seidah NG, Lindberg I. Biosynthesis of the prohormone convertase PC2 in Chinese hamster ovary cells and in rat insulinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:24910–24915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu X, Lindberg I. 7B2 facilitates the maturation of proPC2 in neuroendocrine cells and is required for the expression of enzymatic activity. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:1641–1650. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.6.1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lamango NS, Apletalina E, Liu J, Lindberg I. The proteolytic maturation of prohormone convertase 2 (PC2) is a pH- driven process. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;362:275–282. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindberg I, Zhou Y. Methods in Neuroscience. Academic Press; Orlando: 1995. Overexpression of neuropeptide precursors and processing enzymes; pp. 94–108. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fugere M, Limperis PC, Beaulieu-Audy V, Gagnon F, Lavigne P, Klarskov K, Leduc R, Day R. Inhibitory potency and specificity of subtilase-like pro-protein convertase (SPC) prodomains. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:7648–7656. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107467200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bowman EJ, Siebers A, Altendorf K. Bafilomycins: a class of inhibitors of membrane ATPases from microorganisms, animal cells, and plant cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:7972–7976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.7972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muller L, Cameron A, Fortenberry Y, Apletalina EV, Lindberg I. Processing and sorting of the prohormone convertase 2 propeptide. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39213–39222. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003547200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor NA, Shennan KI, Cutler DF, Docherty K. Mutations within the propeptide, the primary cleavage site or the catalytic site, or deletion of C-terminal sequences, prevents secretion of proPC2 from transfected COS-7 cells. Biochem J. 1997;321:367–373. doi: 10.1042/bj3210367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Molloy SS, Bresnahan PA, Leppla SH, Klimpel KR, Thomas G. Human furin is a calcium-dependent serine endoprotease that recognizes the sequence Arg-X-X-Arg and efficiently cleaves anthrax toxin protective antigen. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:16396–16402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Decroly E, Wouters S, Di Bello C, Lazure C, Ruysschaert JM, Seidah NG. Identification of the paired basic convertases implicated in HIV gp160 processing based on in vitro assays and expression in CD4(+) cell lines. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:30442–30450. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.48.30442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou Y, Lindberg I. Purification and characterization of the prohormone convertase PC1(PC3) J Biol Chem. 1993;268:5615–5623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou Y, Lindberg I. Enzymatic properties of carboxyl-terminally truncated prohormone convertase 1 (PC1/SPC3) and evidence for autocatalytic conversion. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:18408–18413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koo BH, Longpre JM, Somerville RP, Alexander JP, Leduc R, Apte SS. Cell-surface Processing of Pro-ADAMTS9 by Furin. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:12485–12494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511083200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]